Abstract

Rationale: Urban African-American youth, aged 15–19 years, have asthma fatality rates that are higher than in whites and younger children, yet few programs target this population. Traditionally, urban youth are believed to be difficult to engage in health-related programs, both in terms of connecting and convincing.

Objectives: Develop and evaluate a multimedia, web-based asthma management program to specifically target urban high school students. The program uses “tailoring,” in conjunction with theory-based models, to alter behavior through individualized health messages based on the user's beliefs, attitudes, and personal barriers to change.

Methods: High school students reporting asthma symptoms were randomized to receive the tailored program (treatment) or to access generic asthma websites (control). The program was made available on school computers.

Measurements and Main Results: Functional status and medical care use were measured at study initiation and 12 months postbaseline, as were selected management behaviors. The intervention period was 180 days (calculated from baseline). A total of 314 students were randomized (98% African American, 49% Medicaid enrollees; mean age, 15.2 yr). At 12 months, treatment students reported fewer symptom-days, symptom-nights, school days missed, restricted-activity days, and hospitalizations for asthma when compared with control students; adjusted relative risk and 95% confidence intervals were as follows: 0.5 (0.4–0.8), p = 0.003; 0.4 (0.2–0.8), p = 0.009; 0.3 (0.1–0.7), p = 0.006; 0.5 (0.3–0.8), p = 0.02; and 0.2 (0.2–0.9), p = 0.01, respectively. Positive behaviors were more frequently noted among treatment students compared with control students. Cost estimates for program delivery were $6.66 per participating treatment group student.

Conclusions: A web-based, tailored approach to changing negative asthma management behaviors is economical, feasible, and effective in improving asthma outcomes in a traditionally hard-to-reach population.

Keywords: asthma, urban, adolescents, school-based, web-based

AT A GLANCE COMMENTARY

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

From the public health and research perspective, greater inclusion of urban African Americans in research aimed at improving health status is needed. Community-level asthma interventions that are effective, inexpensive, and easily disseminated are also needed.

What This Study Adds to the Field

Web-based and tailored interventions increase program reach and application to asthma and to high-risk populations.

Few programs designed to improve asthma-related health outcomes target urban African-American adolescents. The need for programs directed toward this population is demonstrated by the U.S. 1997–2001 asthma death rate for African Americans aged 15 to 24 years, which is not only 75% higher than that of whites of the same age but is 25% higher than that of African-American youth aged 5 to 14 years, and more than 80% higher than in whites aged 5 to 14 years (1). Recently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported asthma prevalence and attack rates for high school students in grades 9 through 12 that were notably higher than those published previously for elementary school children (2) and were highest for African-American youth compared with whites (2).

National guidelines recommend that patient asthma education include information on asthma medication and the mechanism of action, appropriate technique for using inhalers and spacers, trigger avoidance, and plans for responding to changes in asthma symptoms (3). Asthma education for adolescents should also address depression, unresolved anger at having the disease, denial, and fear of being perceived as weak or different (3–5).

Asthma management issues will vary from person to person. Generic programs seldom have the capacity to address individual needs. Tailoring, defined as the “assessment and provision of feedback based on information that is known or hypothesized to be most relevant for each individual participant of a program,” is one approach to personalizing health information (6). Tailoring can address relevant cultural, social, environmental, and psychological factors, as well as attitudes and health beliefs (7–14). Although surface structure asthma interventions that match messages to observable characteristics of a particular race/ethnic group (e.g., food, music, and language) have been described in the literature, tailoring has not been widely used in asthma management programs geared toward urban adolescents (8, 15).

Web-based disease management tools provide a means of delivering tailored interventions with high fidelity that are easily disseminated to large groups of both clinic- and non–clinic-based populations. Puff City is a program that uses this approach for the purpose of helping urban African-American adolescents gain better control of their asthma by changing negative behaviors related to asthma self-regulation and management. The program was implemented in six Detroit high schools and evaluated using a randomized trial. It was hypothesized that students using the tailored program would have better functional status, less asthma-related medical care use, and higher quality-of-life (QOL) scores than that of students receiving information from existing, generic asthma websites. Some of the results of these studies have been previously reported in the form of an abstract (16).

METHODS

Program Development

Program content for Puff City was based on the recommendations for patient education published in the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program's “Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma: Expert Panel Report II” (EPRII), and includes concepts from other nationally accredited sources (3, 17). All aspects of the program were approved by the Henry Ford Health System (HFHS) and University of Michigan Institutional Review Boards, as well as the Detroit Public School Office of Research, Evaluation, and Assessment.

The web-based program focuses on three core behaviors—namely, controller medication adherence, rescue inhaler availability, and smoking cessation/reduction—and consists of four consecutive educational computer sessions that make use of both normative (“compared with other students”) and ipsative feedback (“compared with your last session”). Messages are voiced over to accommodate low literacy. Participant-specific information necessary for tailoring is obtained at baseline and during the four sessions. Core behavior status is determined at session 1 and reassessed during sessions 2 through 4.

To motivate behavior change in Puff City, tailoring is used to apply the concepts of the transtheoretical model, and the health belief model (13, 18). Theory-based health messages and information on asthma control are presented in reference to these three core behaviors, allowing the delivery of information both central and peripheral to the behavior. Examples of the latter include information on basic asthma pathophysiology, trigger avoidance, and correct use of a metered-dose inhaler and other devices.

Process of identifying eligible students: Lung Health Survey.

Caregivers of all 9th through 11th graders of six Detroit public high schools were notified by mail of a respiratory health survey (Lung Health Survey) to be administered during an English class. To maintain student confidentiality, mailings were conducted by a Detroit Public Schools (DPS) vendor handling student data for the district. Caregivers could opt out of having their child participate by signing and returning the letter to the school. Items on the Lung Health Survey requested information on asthma diagnosis, respiratory symptoms (including items from the International Survey of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood [ISAAC] questionnaire) (19), and health care utilization. The survey was administered by English teachers, using scannable answer sheets preprinted with student identification number, sex, race, and date of birth. Answer sheets were returned to the vendor who destroyed those completed by a student whose guardian opted out of the survey (estimated < 10 forms, or < 1%).

Eligibility criteria for randomized trial.

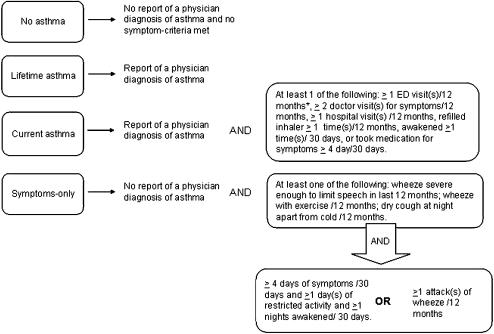

Student eligibility for the randomized trial was determined using Lung Health Survey responses, and criteria were developed using national resources and tools (3, 19, 20). Students were eligible if they met study criteria for current asthma, defined as report of ever having a physician diagnosis of asthma accompanied by one or more of the following: daytime and/or nighttime symptoms in the past 30 days, use of medication for asthma symptoms in the past 30 days, medical care use for asthma in the past year, and one or more refills of β-agonists in the past year (Figure 1). Students were also eligible if they did not report a physician diagnosis, but answered positively to items selected from the ISAAC, and reported symptom frequencies similar to those used in the EPRII for classification of mild, intermittent asthma (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study definitions and inclusion criteria for randomized trial of Puff City Asthma Management Program for urban adolescents. *Last 12 months. ED = emergency department.

Randomized Trial to Evaluate Puff City

Computer access.

Students accessed the program using computers at participating schools. DPS Information Technology worked with HFHS staff to configure a proxy server for the Puff City application, which ran via the DPS network. Another server, located at the University of Michigan Center for Health Communication Research, facilitated data transfer to HFHS on a daily basis.

Baseline and randomization.

Eligible students were mailed an invitation to participate in the randomized trial, together with forms for parental consent and student assent. After completing a baseline questionnaire online, students were randomized, within school, to receive the web-based, tailored program (treatment) or were directed to existing generic asthma education websites (control). Randomization was stratified by school, grade, sex, and report of a physician diagnosis of asthma. A random number generator was used within each unique stratum to assign each new individual to either the treatment or control group. The balance between treatment and control groups was set to occur at random accrual points within each stratum.

Session completion and follow-up.

Students were given 180 days postbaseline to complete the four sessions. The follow-up survey was scheduled 12 months postbaseline. All students were asked to complete the follow-up regardless of the number of sessions completed. All independent variables were collected at baseline, with the exception of behavioral variables, which were collected at the initiation of session 1.

Websites for control students.

Students randomized to the control group were directed to existing generic asthma websites using a combination of Windows (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) system policies and the DPS proxy server. Students were restricted to these sites, and could not access links for outside programs or general-interest sites (e.g., Google). To regulate dosage, control students were given four computer sessions. At each session, control students received a “time expired” message after 30 minutes of browsing. This overall protocol for control students was commensurate with the number of tailored sessions administered to the treatment group, and the estimated maximum time needed to complete a tailored session.

Medications.

To facilitate identification of the student's current medication usage, a program module including names and illustrations of asthma medications was used. This module was implemented for both treatment and control students at the onset of session 1.

Health care referral coordinator.

A study enrollment letter including information on the availability of a referral coordinator was sent to the parents/guardians of all enrolled students, regardless of assignment group. The letter described situations in which the referral coordinator could be helpful (e.g., finding a doctor or obtaining medication). The referral coordinator assessed student needs, made referrals to the appropriate agency or community resource, and followed up all referrals. Referral coordinators did not provide education. A risk assessment report was generated periodically and contained student responses to key questions indicating the need for assistance from the referral coordinator, including report of possible depression, severe and persistent asthma symptoms, sharing asthma medication with a friend or relative, lack of a physician, lack of health insurance, and lack of an asthma inhaler. The risk assessment report was used by the referral coordinator to proactively contact students in the treatment group. The referral coordinator did not initiate contact with students in the control group, except in the case of potentially high-risk situations (e.g., a high score on the depression scale, report of a long-acting β-agonist as the sole controller medication, report of severe symptoms and no medication).

Statistical Analysis

Definitions.

Adherence was defined as self-report of taking controller medication 5 days or more in the last 7 days. Availability of a rescue inhaler was defined as self-report of carrying a rescue inhaler for 5 days or more of the last 7 days. Smoking was defined as self-report of smoking at least two cigarettes on the days smoked in the last 30 days (21).

General statistical methods and bivariate analyses.

Statistical significance was defined as a p value of less than 0.05. Comparisons by participation and by evaluation arm were conducted using chi-square tests for categorical variables accompanied by pairwise comparisons when appropriate. Wilcoxon rank sum test was used for continuous and ordinal variables. Unbiased estimates of mean time to completion from session 1 to session 4 were obtained using the Kaplan-Meier method. Variables found to be related to assignment group and/or study outcomes in bivariate analyses of the randomized trial results were assessed as potential confounders. Potential confounders included the following: sex, age, physician diagnosis of asthma, school at enrollment, Medicaid enrollment, estimated income per person, home environmental tobacco smoke (ETS), student smoking, number of sessions completed, and contact with the referral coordinator (yes/no). Variables found to change the risk estimate for the association of assignment group to study outcomes by 20% or more were included in the final multivariable models.

Measurement and analysis of core behaviors.

Core behavior assessed at session 1 and at 12-month follow-up was categorized as positive (includes maintenance of positive behavior), no change in negative behavior, or negative change (evidence of change from positive behavior to negative behavior). Acquiring a previously unreported medication during the intervention period was considered positive behavior, whereas lack of a medication that was reported earlier was considered a negative change. Treatment/control comparisons for controller medication adherence and rescue inhaler availability were analyzed using multinominal logistic regression to adjust for potential confounders. For smoking behavior, a Fisher's exact test was conducted to compare core behavior categories by evaluation arm. (See Figure E1 of the online supplement for more details.)

Measurement and analysis of study outcomes.

The primary study outcome was number of symptom days in the last 2 weeks. Secondary outcomes included symptom nights, days of restricted activity, days of changed plans, school days missed in last 30 days, asthma-related emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalizations in the last 3 months, and QOL, which was assessed using a tool developed by Juniper and colleagues and included overall and domain-specific scores (22). Treatment/control comparisons of symptom days and other outcomes at the 12-month follow-up were analyzed using negative binomial regression. Adjusted risk ratios (RRs) were calculated with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). QOL scores were analyzed using analysis of covariance.

Estimated cost of program delivery.

Documented time from contact logs combined with wage information from payroll records were used to estimate the cost of providing a referral coordinator. Resultant time estimates were converted to constant, inflation-adjusted dollars using wage and fringe data available at HFHS for an employee with the qualifications needed for the position. Developmental costs were not included in these calculations.

RESULTS

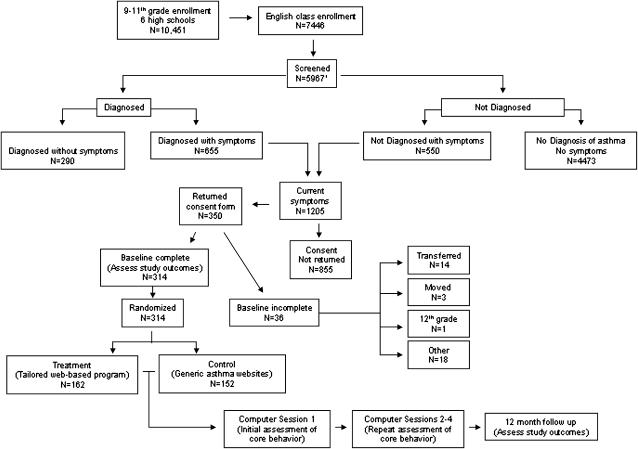

Six high schools participated in the randomized trial, three of which had school-based health clinics. Over 98% of students in the participating schools were African American, and an average of 52% of students across the six schools qualified for federal school lunch programs (23). Less than 0.1% of parents opted out of the Lung Health Survey, and forms for 5,967 students (80%) of 7,446 students enrolled in English class were returned for 143 of 153 English teachers (93%). Of the 10 nonparticipating teachers, 8 were specialists in alternative curricula (special education), and accounted for an estimated 334 (22.6%) of the 1,479 unreturned Lung Health Survey forms, of which 1,205 were eligible (Figure 2). A total of 350 students (29% of eligible) provided assent and consent, of which 314 (89.7% of those consenting) completed a baseline questionnaire and were randomized.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of study participation and randomization. 1Categorization of four students for whom Lung Health Survey forms are missing was achieved using baseline responses.

Using data from the Lung Health Survey, no differences were observed in eligibility criteria across schools or by whether or not the school had a health clinic. The percentage of eligible students returning consent forms at each school ranged from 18.1 to 46.3% (p < 0.001). Differences across schools in mean age were observed (i.e., range, 15.2–15.6 yr; p = 0.009), as were differences in mean household income/person (p < 0.001) and mean ED visits (p = 0.012).

Population Characteristics

Using data from the Lung Health Survey for comparison, participating students were significantly more likely to have a physician diagnosis of asthma, be female, have missed school in the last 30 days, and be classified as having mild, persistent asthma, when compared with nonparticipants (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

COMPARISON OF ELIGIBLE STUDENTS BY STUDY PARTICIPATION USING RESULTS OF THE LUNG HEALTH SURVEY (n = 1,169)*

| Variable | Participants (n = 314) | Nonparticipants (n = 855) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician diagnosis of asthma, % (n) | 69.4 | (219) | 53.4 | (413) | < 0.001† |

| Age, mean (SD), yr | 15.3 | (1.0) | 15.4 | (1.0) | 0.05 |

| Estimated income/person‡, mean (SD) | $12,049 | ($2,442) | $12,286 | ($2,481) | 0.10 |

| Female, % (n) | 63.4 | (199) | 53.9 | (461) | 0.004† |

| Exposed to household ETS, % (n) | 59.2 | (170) | 59.4 | (477) | 0.96† |

| Smoke ⩾ 2/cigarettes on days smoked in last 30 d, % (n) | 5.2 | (15) | 7.7 | (61) | 0.14† |

| Intent to smoke/6 mo, % (n) | 6.1 | (17) | 7.0 | (54) | 0.59† |

| Asthma severity, % (n) | |||||

| Mild, intermittent | 62.6 | (189) | 67.7 | (567) | 0.003†§ |

| Mild, persistent | 19.6 | (59) | 10.9 | (91) | |

| Moderate | 8.9 | (27) | 10.4 | (87) | |

| Severe | 8.9 | (27) | 11.0 | (92) | |

| Functional status, mean (SD) | |||||

| Symptom days in last 30 d | 3.8 | (5.9) | 3.4 | (5.9) | 0.08 |

| Symptom nights in last 30 nights | 2.7 | (5.0) | 2.9 | (6.1) | 0.10 |

| Days of restricted activity in last 30 d | 3.8 | (6.1) | 3.5 | (5.9) | 0.08 |

| Days had to change plans in last 30 d | 1.2 | (3.7) | 1.2 | (3.9) | 0.40 |

| School days missed due to asthma in last 30 d | 1.8 | (4.3) | 1.6 | (4.5) | 0.03 |

| Medical care use, mean (SD) | |||||

| ED visits in last 12 mo | 2.3 | (6.1) | 2.2 | (6.8) | 0.06 |

| Hospitalizations in last 12 mo | 1.0 | (4.6) | 1.1 | (6.8) | 0.41 |

Definition of abbreviations: ED = emergency department; ETS = environmental tobacco smoke.

Thirty-six students returned consent forms but did not complete baseline surveys and were not randomized.

Chi-square test.

Average household income for zip code divided by number of persons residing in that zip code.

Pairwise analysis for participating vs. nonparticipating: mild intermittent, p = 0.10; mild persistent, p < 0.001; moderate persistent, p = 0.47; severe persistent p = 0.31.

After randomization, no significant differences were observed for treatment and control students with regard to eligibility criteria, age, sex, estimated income/person, exposure to ETS at home, smoking behavior, or Medicaid enrollment. Treatment students were more likely to complete all four sessions compared with control students (Table 2). The proportion of treatment students completing the 12-month follow-up, or completing baseline and follow-up in the same season, did not differ from that of control students (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

STUDY COMPLIANCE, STATUS OF CORE BEHAVIOR, AND REPORT OF CONTROLLER AND RESCUE MEDICATION AT SESSION 1 BY RANDOMIZATION GROUP (n = 314)

| p Value

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Control | Overall | Pairwise | |||

| Study activity | ||||||

| Failed to complete even one session, % (n) | 8 | (13) | 13 | (21) | 0.14 | |

| Completed all four sessions, % (n) | 74.1 | (120) | 63.2 | (96) | 0.05 | |

| Days from session 1 to last session completed,* mean (SE) | 102.4 | (5.4) | 98.7 | (5.0) | 0.73 | |

| Completed a 12-mo follow-up, % (n) | 86 | (139) | 88 | (134) | 0.54 | |

| Completed baseline and 12-mo follow-up in same season, % (n) | 70.5 | (98) | 64.2 | (86) | 0.26 | |

| Core behavior and report of medication at session 1 | ||||||

| No controller medication reported, % (n) | 66.4 | (101) | 53.9 | (77) | 0.02† | 0.01 |

| Among students reporting a controller medication: | ||||||

| Controller medication, adherent ⩾ 5 of last 7 d | 8.6 | (13) | 7.7 | (11) | 0.69 | |

| Controller medication, not adherent < 5 of last 7 d | 25.0 | (38) | 38.5 | (55) | < 0.01 | |

| No rescue inhaler reported, % (n) | 59.9 | (91) | 37.1 | (53) | < 0.01† | < 0.01 |

| Among students reporting a controller medication | ||||||

| Rescue inhaler available ⩾ 5 of last 7 d | 17.1 | (26) | 25.2 | (36) | 0.09 | |

| No rescue inhaler available < 5 of last 7 d | 23.0 | (35) | 37.8 | (54) | < 0.01 | |

| Nonsmoker, % (n) | 61.8 | (92) | 68.7 | (92) | 0.41‡ | |

| Smoker, ⩾ 2 cigarettes in last 30 d, % (n) | 8.7 | (13) | 6.7 | (9) | ||

| Smoker, < 2 cigarettes in last 30 d, % (n) | 29.5 | (44) | 24.6 | (33) | ||

Regardless of number of sessions completed.

Adjusted for school at enrollment and severity at session 1 using multinomial logistic regression.

Chi-square test.

Study Outcomes

At session 1, significantly fewer treatment students reported a controller medication compared with control students (Table 2). Among students with a controller medication, significantly fewer treatment students were adherent compared with control students. A similar trend was observed for report of a rescue medication and rescue medication availability (Table 2). No significant differences were observed for smoking behavior between treatment and control students at session 1.

Analysis results for core behaviors and acquiring medications are presented in Table 3. Few changes in core behaviors reached statistical significance. Overall, treatment students showed more positive change and less negative change than control students. Positive changes in controller medication adherence were of borderline significance (p = 0.09). Significantly less negative change was observed for rescue inhaler availability (p for pairwise comparison, 0.003). Restricting the analysis of core behavior in Table 3 to students meeting study criteria for “persistent” asthma did not alter results (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

CORE BEHAVIOR STATUS AND STUDY OUTCOMES AT 12-MONTH FOLLOW-UP (n = 314)

| Treatment | Control | Adjusted RR (95% CI) | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controller medication adherence, % (n) | ||||||

| Positive behavior | 20.4 | (31) | 12.6 | (18) | 0.09* | |

| No change in negative behavior | 62.5 | (95) | 63.6 | (91) | ||

| Negative change in behavior | 17.1 | (26) | 23.8 | (34) | ||

| Rescue inhaler availability, % (n) | ||||||

| Positive behavior | 38.8 | (59) | 32.2 | (46) | 0.01*† | |

| No change in negative behavior | 48.7 | (74) | 43.3 | (62) | ||

| Negative change in behavior | 12.5 | (19) | 24.5 | (35) | ||

| Smoking cessation/reduction, % (n) | ||||||

| Positive behavior | 95.0 | (132) | 94.1 | (111) | 0.89‡ | |

| No change in negative behavior | 0.7 | (1) | 0.8 | (1) | ||

| Negative change in behavior | 4.3 | (6) | 5.1 | (6) | ||

| Symptom days/2 wk | 2.1 | (3.0) | 2.8 | (3.4) | 0.5 (0.4–0.8) | 0.003§ |

| Symptom nights/ 2 wk | 0.9 | (2.3) | 1.5 | (2.5) | 0.4 (0.2–0.8) | 0.009 |

| School days missed/30 d | 0.4 | (1.2) | 1.2 | (3.3) | 0.3 (0.1–0.7) | 0.006 |

| Days restricted activity/2 wk | 1.3 | (2.2) | 2.3 | (3.4) | 0.5 (0.3–0.8) | 0.02 |

| Days had to change plans | 0.4 | (1.2) | 0.6 | (1.5) | 0.5 (0.3–1.2) | 0.17 |

| Hospitalizations/12 mo | 0.2 | (0.6) | 0.6 | (2.0) | 0.2 (0.2–0.9) | 0.01 |

| ED visits/12 mo | 0.5 | (2.0) | 0.8 | (1.9) | 0.5 (0.3–1.3) | 0.08 |

| QOL, cumulative score | 5.3 | (1.3) | 5.0 | (1.5) | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) | 0.35‖ |

| QOL, activity domain | 5.3 | (1.7) | 5.0 | (1.7) | 1.4 (1.0–2.0) | 0.16 |

| QOL, emotional domain | 5.7 | (1.5) | 5.3 | (1.6) | 1.2 (0.9–1.7) | 0.38 |

| QOL, symptom domain | 5.3 | (1.6) | 4.9 | (1.6) | 1.4 (1.0–1.9) | 0.07 |

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; ED = emergency department; QOL = quality of life; RR = risk ratio.

Adjusted for severity at session 1 and school of enrollment using multinomial logistic regression.

Pairwise analysis for treatment vs. control: positive change = 0.20; neutral = 0.25; negative change, p = 0.003.

Fisher's exact test.

Negative binomial regression, adjusting for baseline measurement, baseline asthma severity, school of enrollment, and contact with referral coordinator.

Analysis of covariance used to test for 12-mo differences, adjusting for baseline measurement, baseline asthma severity, school of enrollment, and contact with referral coordinator.

Table 3 shows results for the analysis of treatment assignment to functional status, medical care use, and QOL at 12 months. After adjusting for baseline measures, baseline asthma severity, school of enrollment, and contact with the referral coordinator, students in the treatment group reported significantly fewer symptom days than control students (p = 0.003), as well as symptom nights (p = 0.009), school days missed (p = 0.006), and days of restricted activity (p = 0.01) (Table 3). Asthma hospitalizations were significantly lower for treatment students when compared with control students (p = 0.01). Days of changed plans and ED visits for asthma were also lower for treatment students compared with control students, but the differences were only marginally significant. At 12 months, treatment students had higher QOL scores than control students in the activity domain. In addition, for treatment students, QOL at 12 months was similar to that reported at baseline, but for control students, symptom QOL at 12 months was lower than that reported at baseline.

Adjusted RRs for the association of treatment group assignment to study outcome are also presented in Table 3. Results can be interpreted as the risk of decreased functional status, increased morbidity, and increased QOL given a treatment group assignment. Models in Table 3 were also run adjusting for sex, age, physician diagnosis of asthma, Medicaid enrollment, estimated income per person, home ETS, student smoking, and number of sessions completed, with no appreciable change in results.

The likelihood of obtaining a controller asthma medication by the 12-month follow-up was assessed for students who did not report having the medication at session 1 (data not shown). Persons in the treatment group were twice as likely to obtain a controller medication than control students (RR, 2.4; 95% CI, 1.0–5.7; p = 0.04); and mean number of physician visits was significantly higher for students who had obtained a controller medication compared with those who did not (1.1 vs. 0.3 visits, respectively; p = 0.02). Obtaining a controller medication was not related to seeing the referral coordinator (RR, 1.0; 95% CI, 0.4–2.3; p = 0.97) (data not shown).

Two secondary analyses were performed. To assess a potential floor effect in behavior change, data were analyzed and stratified by behavior status at baseline. No evidence of a floor effect in behavior change was observed (see Table E1). To further explore the role of the referral coordinator in the relationship of assignment group to study outcomes, we performed a secondary analysis stratified by whether or not the student had visited the referral coordinator (see Table E2). Although the loss in power resulted in fewer statistically significant associations, the trend of a positive association between treatment assignment and study outcomes was maintained for both levels of the referral coordinator variable (see Table E2).

Cost estimates.

Because all schools had existing computer resources, providing a referral coordinator was the major cost in program delivery. A total of 134 (82.7%) treatment students met criteria for contact by the referral coordinator, compared with 107 (70.4%) control students (p = 0.01). The top three reasons for referral (not mutually exclusive) for treatment versus control students were lack of a physician (67.3 vs. 64.5%), no inhaler (41.8 vs. 42.0%), and possible depression (35.1 vs. 29.9%). Of the treatment students referred, 79 (60%) were successfully contacted by the referral coordinator. (Seven control students were followed due to potentially high-risk situations, four of whom were successfully contacted.) Estimated labor cost for the referral coordinator was $6.66 per treatment student ($8.05 per treatment student referred; $11.73 per student contacted). Contacts averaged 31 minutes per student.

DISCUSSION

Innovative and theory-based approaches to asthma management and self-regulation are sorely needed for adolescents with asthma, especially for urban, low-income, and African-American youth who may have few resources and a tenuous connection with the health care system (24). Several multimedia approaches to asthma self-regulation have appeared in the literature. Peer-led programs have shown some success in terms of improved QOL and reductions in school absenteeism among high school students in Australia (25). IMPACT (Interactive Multimedia Program for Asthma Control and Tracking) is a clinic-based program that targets children and adolescents, but to our knowledge has not been evaluated in an urban population (26). Health Buddy, a hand-held interactive tool for asthma, was evaluated in urban children and had positive results, although the number of adolescents included in the evaluation was unclear (27). The Asthma Management Demonstration Project, a part of the theory-based eHealth Behavior Management model, targets university students through campus kiosks and is currently undergoing evaluation (28).

To our knowledge, Puff City is the first tailored, web-based multimedia asthma program for urban high school students evaluated in a non–clinic-based community setting. Results suggest that, for students in the treatment arm, functional status was significantly improved and asthma morbidity was significantly reduced when compared with a control group with access to generic asthma education websites.

Our results support earlier reports that it is difficult to change health behavior, especially in adolescents (29). We observed less negative change among treatment students when compared with control students, followed by gains and maintenance of positive behavior. The concept of maintaining positive behavior could be important because positive behavior initiated after an acute event tends to diminish with time (30). The addition of booster sessions may aid in the maintenance of positive changes in behavior.

Attributing study results to any one aspect of a multifaceted asthma intervention can be difficult, but the ability to do so can yield a more accurate understanding of the relationship of behavior change to study outcomes. We were able to isolate and measure changes in core behaviors and adjust for other study aspects, such as contact with the referral coordinator, to more closely examine the effect of tailored messages. In analyses stratified by this variable, favorable health outcomes were observed for treatment students, whether or not they had been contacted by the referral coordinator. Results support our reasoning that improved asthma outcomes in this population will require attention to behavior as well as health care access. We acknowledge that observed differences in outcomes may be due to unmeasured participant characteristics, changes in health care access, or changes in behaviors not assessed in this evaluation.

Because all schools had existing computer resources, providing a referral coordinator was the major cost in program delivery. The study suggests that socioeconomic or contextual factors are often obstacles to managing asthma among adolescents. As such, we feel strongly that inclusion of this referral mechanism is necessary, and caution against excluding this aspect of the program as a cost savings.

The potential for cost savings is feasible given the reduction in self-reported medical care use. Financial advantages would accrue to insurers as reduced expenditures on medical care (i.e., direct costs), or to other stakeholders in the form of reduced indirect costs (e.g., days lost from work or school).

The impact of the intervention on smoking behavior is inconclusive. Analysis was hampered by the low prevalence of smoking in our study, although the 6.5% of smokers reported through the Lung Health Survey is higher than the 3.4% (2.3–4.4%) reported for the general population of Detroit high school students in 2003 (31). The inconsistent nature of adolescent smoking also makes detection of true changes in smoking behavior problematic (32).

Generalization of our results may be limited to students with characteristics similar to those participating in this study. Differences in characteristics by participation are important in considering generalizability, but should not alter results of a randomized trial. Our comparison of participants with nonparticipants suggests that, in terms of functional status and asthma morbidity, nonparticipants were not sicker than participants. However, other factors related to enrollment may be associated with asthma management and may have implications for our findings. In our experience, and as noted in the literature, the process of consent is a major obstacle to participation, especially among the urban poor (33). Program awareness also seemed a major issue. We surveyed 35 eligible, but nonparticipating students, and found that 51% reported not knowing about the program and 25% reported that they did not receive the introductory packet. Similar responses were obtained when caregivers of nonparticipants were surveyed. High mobility may have been related to reduced awareness and program participation. We obtained 12-month follow-up data on 87% of study participants, despite the fact that 30% of students changed addresses and/or transferred schools during the study period. Clearly, prodigious efforts are necessary in promoting program awareness as well as follow-up, especially in populations where high percentages of students/families may be more transient or mobile. High mobility is likely related to less adequate asthma management and control.

Several lessons in recruitment of urban adolescents were learned from this trial. Obvious sex differences in participation were observed. According to the literature, student unease about being labeled as having asthma is less a concern for females than for males (34). Although incentives only moderately impacted enrollment (62% of students reported participating to “learn more/better manage asthma” compared with 7% who reported participating because of incentives), incentives seemed more of a draw for boys compared with girls (10.6 vs. 5.2%). Participation was also highest for the three schools that had school-based clinics or health services compared with those that did not (35 vs. 23%). Strategies for engaging urban adolescents in health-related interventions need further exploration.

Our results support previous reports of prevalent underdiagnosis and undertreatment of asthma among adolescents. At least two studies suggest that undiagnosed youth can benefit from asthma interventions, but the true context of being “undiagnosed” is unclear. There is consensus that undertreatment of symptoms should be addressed, regardless of report of a diagnosis.

The full potential of online disease management programs has yet to be realized, but it is clear that web-based approaches facilitate dissemination and improve fidelity. We found that a web-based, tailored, and theory-based intervention can lead to greater involvement and cognitive processing of asthma information than generic programs, ultimately leading to better outcomes (9, 35, 36). Making the program school based ensured greater access. The approach and framework used in this program can be applied to other health conditions, such as diabetes, and other high-risk populations, such as rural or Latino youth. More research is needed on the types of interventions that can successfully engage urban adolescents with chronic disease, and the enhancement of participation in such programs.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate and acknowledge the collaboration of the Detroit Public School System and the principals of the following Detroit Public high schools: Cody, Henry Ford, Mackenzie, Mumford, Northwestern, and Redford. These principals exhibit a deep concern for the health and welfare of their students. We also acknowledge Ms. Anntinette McCain of the Office of Health, Physical Education & Safety and Ms. Sybil St. Clair of the Office of Research, Evaluation, and Assessment for their guidance and advice.

Asthma in Adolescents Research Team, in alphabetical order: Al Bliss, Cleo Caldwell, Jann Caison-Sorey, Noreen Clark, Ian Jones, Anntinette McCain, Dan McLaren, Jonathan Mitchell, Mike Nowak, Edward Saunders, Anthony Wahlman, Kevin Wildenhaus, and Rick Vinuya.

Supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant R01 HL068971-05).

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.200608-1244OC on February 8, 2007

Conflict of Interest Statement: C.L.M.J. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. E.P. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. S.H. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. C.C.J. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. S.H. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. S.S. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. W.G.-S. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. D.R.O. has served on a consulting basis to the Chlorine Council of America since January 2005, concerning the effects of chlorination on the risks of asthma in children, for $1,500. In November 2004, he also lectured on the use of Xolair in asthma for Genentech for $1,000. He has also served on an advisory board for Greer Laboratories on the use of sublingual immunotherapy in allergic disease since April 2005 for $2,000 and received $5,000 for an Allergy Fellowship Review from GlaxoSmithKline. J.E.-L. received $400,000 for 2005–2006 from Sanofi-Aventis as a research grant, served as a coinvestigator on research grants totaling $562,877 from Teva from 2005 to 2007, received $373,414 from Merck & Co. for 2003–2005, and received $124,000 from GlaxoSmithKline in 2003. U.P. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. V.S. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics, Health E-Stats: asthma prevalence, health care use, and mortality, 2002. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Center For Health Statistics; 2003.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Self-reported asthma among high school students: United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2005;54:765–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma: expert panel report 2. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1997. NIH Publication No. 97–4051.

- 4.Abrams RB. Adolescent health problems: a model for their solution. Henry Ford Hosp Med J 1990;38:160–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gavin LA, Wamboldt MZ, Sorokin N, Levy SY, Wamboldt FS. Treatment alliance and its association with family functioning, adherence, and medical outcome in adolescents with severe, chronic asthma. J Pediatr Psychol 1999;24:355–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moorthy KS. Market segmentation, self-selection, and product line design. Marketing Science 1984;3:288–307. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Resnicow K, Braithwaite RL. Cultural sensitivity in public health. In: Braithwaite RL, Taylor S, editors. Health issues in the black community, 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2001.pp. 516–542.

- 8.Lancaster T, Stead L, Shepperd S. Helping parents to stop smoking: which interventions are effective? Paediatr Respir Rev 2001;2:222–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Redding C, Prochaska J, Pallonen U, Rossi J, Velicer W, Rossi S, Greene G, Meier K, Evers K, Plummer B, et al. Transtheorectical individualized Multimedia Expert Systems Targeting Adolescents' Health Behaviors. Cogn Behav Pract 1999;6:144–153. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orleans C, Boyd N, Bingler R, Sutton C, Fairclough D, Heller D, McClatchey M, Ward J, Graces C, Fleisha L, et al. Self-help intervention for African American smokers: tailoring cancer information service counseling for a special population. Prev Med 1998;27:S61–S70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skinner CS, Strecher VJ, Hospers H. Physicians' recommendations for mammography: do tailored messages make a difference? Am J Public Health 1994;84:43–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Resnicow K, Royce J, Vaughan R, Orlandi MA, Smith M. Analysis of a multicomponent smoking cessation project: what worked and why. Prev Med 1997;26:373–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol 1983;51:390–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams GC, Cox EM, Kouides R, Deci EL. Presenting the facts about smoking to adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1999;153:959–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cochrane MG, Bala MV, Downs KE, Mauskopf J, Ben-Joseph RH. Inhaled corticosteroids for asthma therapy: patient compliance, devices, and inhalation technique. Chest 2000;117:542–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joseph CLM, Stringer S, Ownby DR, Peterson E, Hoerauf S, Gibson-Scipio W, Johnson CC, Elston-Lafata J, Saunders E, Pallonen U, et al. Preliminary results of the Puff City program for urban teens with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005;115(Suppl):S63. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Croft DR, Peterson MW. An evaluation of the quality and contents of asthma education on the World Wide Web. Chest 2002;121:1301–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenstock I. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Educ Monogr 1974;2:4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weiland SK, Bjorksten B, Brunekreef B, Cookson WO, von Mutius E, Strachan DP. Phase II of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC II): rationale and methods. Eur Respir J 2004;24:406–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists. Surveillance asthma prevalence definition, 1998. Available from: http://www.cste.org/ps/1998/1998-eh-cd-01.htm (accessed April 27, 2005).

- 21.Grunbaum JA, Kann L, Kinchen S, Ross J, Hawkins J, Lowry R, Harris WA, McManus T, Chyen D, Collins J. Youth risk behavior surveillance: United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2004;53:1–96. [Published erratum appears in MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2004;53:536.] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Willan A, Griffith LE. Determining a minimal important change in a disease-specific quality of life questionnaire. J Clin Epidemiol 1994;47:81–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). U.S. Department of Education [homepage]. Available from: http://nces.ed.gov (accessed March, 2007).

- 24.Ford CA, Bearman PS, Moody J. Foregone health care among adolescents. JAMA 1999;282:2227–2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah S, Peat JK, Mazurski EJ, Wang H, Sindhusake D, Bruce C, Henry RL, Gibson PG. Effect of peer led programme for asthma education in adolescents: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2001;322:583–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krishna S, Francisco B, Balas A, Konig P, Graff G, Madsen R. Internet-enabled interactive multimedia asthma education program: a randomized trial. An Pediatr (Barc) 2003;11:503–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guendelman S, Meade K, Benson M, Chen Y, Samuels S. Improving asthma outcomes and self-management behaviors of inner-city children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2002;156:114–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bensley RJ, Mercer N, Brusk JJ, Underhile R, Rivas J, Anderson J, Kelleher D, Lupella M, de Jager AC. The eHealth Behavior Management Model: a stage-based approach to behavior change and management [abstract]. Prev Chronic Dis 2004;1:A14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berry T, Naylor PJ, Wharf-Higgins J. Stages of change in adolescents: an examination of self-efficacy, decisional balance, and reasons for relapse. J Adolesc Health 2005;37:452–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stempel DA, Roberts CS, Stanford RH. Treatment patterns in the months prior to and after asthma-related emergency department visit. Chest 2004;126:75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth risk behavior surveillance: United States, 1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2000;49:24. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mermelstein R, Colby SM, Patten C, Prokhorov A, Brown R, Myers M, Adelman W, Hudmon K, McDonald P. Methodological issues in measuring treatment outcome in adolescent smoking cessation studies. Nicotine Tob Res 2002;4:395–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moberg D, Piper D. Obtaining active parental consent via telephone in adolescent substance abuse prevention. Eval Rev 1990;14:315–323. [Google Scholar]

- 34.McKenna H. Adolescents managed their asthma or diabetes in gendered ways with the aim of projecting different gendered identities. Evid Based Ment Health 2000;3:125. [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Bourdeaudhuij I, Brug J. Tailoring dietary feedback to reduce fat intake: an intervention at the family level. Health Educ Res 2000;15:449–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pallonen UE, Velicer WF, Prochaska JO, Rossi JS, Bellis JM, Tsoh JY, Migneault JP, Smith NF, Prokhorov AV. Computer-based smoking cessation interventions in adolescents: description, feasibility, and six-month follow-up findings. Subst Use Misuse 1998;33:935–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]