Abstract

Inhalation of crystalline silica results in pulmonary fibrosis and silicosis. It has been suggested that mast cells play a role in these conditions. How mast cells would influence pathology is unknown. We thus explored mast cell interactions with silica in vitro and in B6.Cg-kitW-sh mast cell–deficient mice. B6.Cg-kitW-sh mice did not develop inflammation or significant collagen deposition after instillation of silica, while C57Bl/6 wild-type mice did have these findings. Given this supporting evidence of a role for mast cells in the development of silicosis, we examined the ability of silica to activate mouse bone marrow–derived mast cells (BMMC), including degranulation (β-hexosaminidase release); production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and inflammatory mediators; and the effects of silica on FcεRI-dependent activation. Silica did not induce mast cell degranulation. However, TNF-α, IL-13, monocyte chemotactic protein-1, protease activity, and production of ROS were dose-dependently increased after silica exposure, and production was enhanced after FcεRI stimulation. This mast cell activation was inhibited by anti-inflammatory compounds. As silica mediates some effects in macrophages through scavenger receptors (SRs), we first determined that mast cells express scavenger receptors; then explored the involvement of SR-A and macrophage receptor with colleagenous structure (MARCO). Silica-induced ROS formation, apoptosis, and TNF-α production were reduced in BMMC obtained from SR-A, MARCO, and SR-A/MARCO knockout mice. These findings demonstrate that silica directs mast cell production of inflammatory mediators, in part through SRs, providing insight into critical events in the pathogenesis and potential therapeutic targets in silicosis.

Keywords: B6.Cg-kitW-sh sash mouse, CD204, macrophage receptor with collagenous structure, mast cell, silicosis, SR-A

CLINICAL RELEVANCE

This study demonstrates a role for mast cells in silicosis and is the first study to examine direct effects of silica on mast cell biology. It provides evidence that treatment of silicosis should explore mast cells as a potential therapeutic target.

Among environmental exposures that lead to pathologic changes in tissues is crystalline silica, which can result in occupational silicosis from inhalation of silica dusts in manufacturing, construction, farming, and mining operations. Silicosis, for which there is no effective treatment, leads to decreased pulmonary function and increased susceptibility to diseases of the respiratory tract (1, 2).

Involvement of mast cells in silica-induced pulmonary inflammation has been suggested by two clinical observations. First, the number of mast cells within the lungs of individuals exposed to silica dust is increased (3). Second, an increase in mast cells staining for basic fibroblast growth factor located within silicotic nodules has been reported in lung sections obtained from patients with silicosis (4). Despite the suggestive evidence for a role of mast cells in the development of silicosis, there are no systematic studies of the effects of silica on mast cells.

Before entering into experiments testing the hypothesis that silica can direct mast cell activation, a critical role for mast cells in promoting silicosis was first verified in mast cell–deficient sash mice (B6.Cg-kitW-sh) after exposure to silica. Because the mast cell–deficient mice did not develop silicosis, while mice with normal mast cells did develop pathology, we entered into experiments to determine the ability of silica to directly activate mast cells. Cultured bone marrow–derived murine mast cells (BMMC) were exposed to silica, followed by analysis of cell viability, for effects on degranulation, and for the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), cytokines, and proteolytic activity. The possible role of scavenger receptor class A (SR-A) and macrophage receptor with collagenous structure (MARCO) was explored in the genesis of positive responses to silica exposure. As will be shown, mast cells exposed to silica respond primarily by production of cytokines, the synthesis of which can be inhibited with anti-inflammatory agents and is enhanced by scavenger receptors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture and Silica Treatment

Mouse BMMC were cultured from femoral marrow cells of C57Bl/6 wild-type, SR-A KO, MARCO KO, and SR-A/MARCO double knockout (KO) mice. Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 25 mM HEPES, 1.0 mM sodium pyruvate, nonessential amino acids (BioSource International, Camarillo, CA), 0.0035% 2-ME, and 300 ng/ml recombinant mouse IL-3 (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ). BMMC were used after 4–6 wk of culture. Silica (Min-U-Sil-5, with an average particle size of 1.5–2 μm) was obtained from Pennsylvania Glass Sand Corporation (Pittsburgh, PA) and was acid washed, dried, and determined to be free of endotoxin. Cells were treated with silica in 96-well plates at 0, 6.25, 12.5, 25, or 50 μg/cm2. Water-soluble dexamethasone (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used at 10−6 M and was added to BMMC cultures 1 h before the addition of silica.

Mice

Mast cell–deficient sash mice (B6.Cg-kitW-sh) and wild-type (C57Bl/6) mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories at 4–6 wk of age (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were anesthetized with tribromoethanol (0.1 mg/kg) before intranasal instillation of either 30 μl sterile saline or a 30 μl sterile saline suspension of 1 mg crystalline silica. All mice received two instillations 2 wk apart. Six mice were instilled per group, and the four groups consisted of C57Bl/6 wild-type mice or B6.Cg-kitW-sh mast cell–deficient mice instilled with either saline or silica. Mice were killed 3 mo after the first instillation of silica.

SR-AI/II KO mice and MARCO KO mice were generously provided by Dr. L. Kobzick of the Harvard School of Public Health (Boston, MA) (5, 6). Both knockouts were backcrossed for at least eight generations to the C57Bl/6 background. SR-A I/II/MARCO double KO mice were generated in the laboratory of Dr. L. Kobzik by intercross of the single SR-A I/II and MARCO knockouts. Founding C57Bl/6 wild-type mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. Mice used in these studies were propagated by homozygous mating colonies and maintained in microisolator units within the University of Montana specific pathogen–free animal facility. Cages, bedding, and food were sterilized by autoclaving, and mice were handled with aseptic forceps or aseptic gloves. Mice were allowed food and water ad libitum and were used experimentally between 6 and 8 wk of age. All animal use procedures were in accordance with National Institutes of Health and approved by the University of Montana institutional animal care and use committee.

Identification of SR-A I/II and MARCO KO Mice

DNA samples were extracted from mouse tail and amplified using forward (5′-CAAGTGATACATCTCAAGGTC-3′), reverse (5′-CTGTAGATTCACGGACTCTG-3′), and Neo insert (5′-GAGGAGTAGAAGGTGGCGCGAA-3′) primers (Operon Technologies, Alameda, CA) encompassing the site of the SR-A I/II and Neo insert (7). For MARCO idenfication, DNA samples were amplified using the following primers: MARCO WT, forward (5′-CAGCTGGGTCCATACCAGC-3′) and reverse (5′-CTGGAGAGCCTCGTTGACC-3′); and MARCO KO, forward (5′-CCACGCTCATCGATAATTTCAC-3′) and reverse (5′-CCTGCAGTGGCCGTCGTTTTA-3′). Amplification was performed in a PTC-200 Gradient Cycler (MJ Research, Las Vegas, NV) with the following parameters: 1 min 94°C, 1 min 60°C, 1 min 72°C and subjected to 35 cycles of PCR. Genotyping was determined by separation of the amplified PCR products by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis at 75 V for 2.5 h. C57Bl/6 WT mice show a 440-bp band, whereas SR-A I/II KO mice show a 325-bp band. MARCO WT primers produce a 500-bp band and MARCO KO primers produce an 850-bp band.

Lung Histology

Three months after either saline or silica instillation, C57Bl/6 wild-type and B6.Cg-kitW-sh mast cell–deficient mice were given a lethal dose of sodium pentobarbital. Lungs were then perfused with 1–2 ml Histochoice fixative (Amresco, Solon, OH), embedded in paraffin blocks and sectioned at 5 μm, and mounted on glass slides (American HistoLabs, Inc, Gaithersburg, MD) (8). Sections were stained with Gomori's trichrome, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and toluidine blue (American HistoLabs).

Cell Viability and Apoptosis

Cell viability was determined by trypan blue staining and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release (9). The percentage of LDH release was measured in supernatants of BMMC exposed to silica for 24 h (BioVision, Mountain View, CA). Untreated cells were used as a negative control and 1%-triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich)–treated BMMC were used as a positive control, representing 100% LDH release. Apoptosis was determined by DNA fragmentation using a TiterTacs TUNEL Assay (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) (10). Equal numbers of cells (1 × 105/well) were plated in a 96-well plate, and silica was added for 24 h at 6.25, 12.5, 25, or 50 μg/cm2. Nontreated cells were used as a negative control and a DNA nuclease–generated positive control was used. Experiments were repeated three times. The reported values are mean optical density (OD) values from each treatment.

Degranulation and Cytokine Release

BMMC were seeded at 5 × 104 cells/well in 96-well flat-bottom plates and sensitized with 100 ng/ml mouse IgE anti-DNP (Sigma-Aldrich) for 24 h for degranulation experiments (11). For treated samples, silica was added at 0, 6.25, 12.5, 25, or 50 μg/cm2 for 24 h before addition of increasing concentrations of DNP-HSA (0–1000 ng/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich). After 30 min incubation of antigen at 37°C, p-nitrophenyl-N-acteyl-β-D-glucopyranoside was added to cell supernatants and lysates for 90 min as a chromogenic substrate for N-acetyl-β-D-hexosaminidase (Sigma-Aldrich) (11). The reaction was stopped with 0.2 M glycine. Optical density was measured at 405 nm using a GENios ELISA plate reader (ReTirSoft, Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada). β-Hexosaminidase release was expressed as the percentage of total cell content after subtracting background release from unstimulated cells. Cytokines were measured in cell culture supernatant of BMMC seeded at 2 × 105 cells/well for 24 h after addition of 6.25, 12.5, 25, or 50 μg/cm2 silica. For experiments with silica exposure and FcεRI stimulation, BMMC were exposed to silica for a total of 24 h at 0–50 μg/cm2 and sensitized overnight with 100 ng/ml IgE anti-DNP (Sigma-Aldrich). DNP-HSA (Sigma-Aldrich) was added at 100 ng/ml for a total of 8 h before supernatant collection for cytokine analysis. Mouse TNF-α, IL-13, and monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP)-1 (CCL2) were measured using Quantikine ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Protease Assay

Silica-exposed BMMC were examined for protease activity using a Quanticleave Protease Assay Kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Briefly, supernatants from BMMC exposed to 0, 6.25, 12.5, 25, or 50 μg/cm2 silica for 24 h were collected and analyzed for the ability to cleave succinylated casein. A control blank without casein from each sample was run in parallel and subtracted as background. Experiments were repeated three times. The reported values are mean OD values measured at 450 nm.

Reactive Oxygen Species Detection

ROS were measured by a 96-well plate assay employing the fluorescent probe dichlorofluoroscein (DCF) (12). BMMC (1 × 106/ml) were incubated with DCF diacetate (20 μM) in cell culture medium for 15 min at 4°C with rotation. Cells were then washed in HEPES buffer (10 ml) and seeded at 200,000 per well in a black opaque 96-well microplate. Zileuton (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) and Trolox (EMD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) (10 μl) were added and DCF fluorescence monitored for 5 min before the addition of silica. After addition of silica, DCF fluorescence was then monitored for a further 10 min using a GENios fluorescent plate reader (ReTirSoft Inc.) set at an excitation wavelength of 492 nm and emission wavelength of 535 nm. Fluorescence was expressed as relative fluorescent units (RFU). The kinetic data was collected using an XFlour4 macro within Microsoft Excel.

RT-PCR

BMMC (1 × 106 cells/condition) from C57Bl/6 mice were exposed to silica for 30 min, 1 h, or 2 h at 0, 6.25, 12.5, 25, or 50 μg/cm2. Cells were collected and total mRNA was isolated using QIAshredders and RNeasy Mini Kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA was transcribed to cDNA using a Reaction Ready First Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Superarray, Frederick, MD). Gene-specific primers for SR-A I (MSR1), SR-A II (MSR2), MARCO, and glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were purchased from Superarray and transcripts were amplified using a Reaction Ready Hotstart “Sweet” PCR kit according to manufacturer's instructions (Superarray).

Statistics

Statistical analysis employed the software package PRISM, version 4 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). Differences between untreated and silica-treated samples were assessed using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test. Area under the curve (AUC) was calculated for ROS measurements using PRISM. All values are reported as means ± SEM.

RESULTS

Mast Cell–Deficient Mice Fail to Develop Inflammation and Extensive Collagen Deposition after Silica Exposure

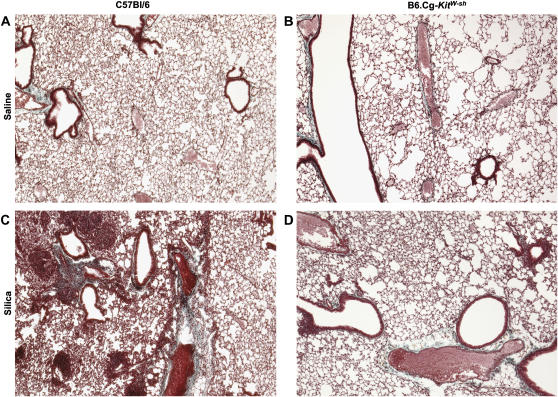

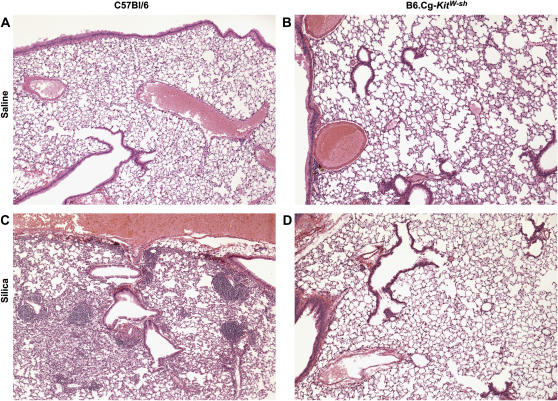

To assess the role of mast cells in the development of silicosis, mast cell–deficient mice (B6.Cg-kitW-sh) were administered two 1-mg instillations of silica, with effects on lung histology examined 3 mo after the first instillation of silica. As determined by Gomori's trichrome staining, silica-exposed wild-type mice demonstrated increased collagen deposition within the lung as compared with saline-instilled wild-type mice (compare Figure 1A with 1C). By H&E staining, wild-type mice were found to have developed granulomatous lesions typical of silicotic lesions, alveolar thickening, and pronounced inflammatory infiltrates within the interstitial and alveolar spaces (compare Figure 2A with 2B). In contrast, mast cell–deficient mice exposed to silica did not develop granulomatous lesions, alveolar thickening, or any significant inflammation or collagen deposition (compare Figures 1D and 2D with 1C and 2C). There were no differences in the number of lung mast cells in silica-exposed wild-type mice as compared with saline controls (data not shown). As expected, no mast cells were detectable in B6.Cg-kitW-sh mast cell–deficient mouse lungs, and no mast cells were observed after silica exposure (data not shown). These observations confirm a role for mast cells in silicosis.

Figure 1.

Silica induces collagen deposition in C57Bl/6 wild-type, but not B6.Cg-kitW-sh mast cell–deficient mouse lungs 3 mo after two intranasal instillations of 1 mg silica. C57Bl/6 mice were instilled with either saline (A) or silica (C). B6.Cg-kitW-sh received instillations of either saline (B) or silica (D). Lungs were stained with Gomori's trichrome stain to examine collagen deposition. Images were obtained at ×5 magnification and are representative of six mice per group.

Figure 2.

Silica induces inflammation in C57Bl/6 wild-type, but not B6.Cg-kitW-sh mast cell–deficient mouse lungs 3 mo after two intranasal instillations of 1 mg silica. C57Bl/6 mice were instilled with either saline (A) or silica (C). B6.Cg-kitW-sh received instillations of either saline (B) or silica (D). Lungs were stained with H&E to examine inflammation. Images were obtained at ×5 magnification and are representative of six mice per group.

Silica Induces Apoptosis in BMMC but Has Minimal Effect on Degranulation

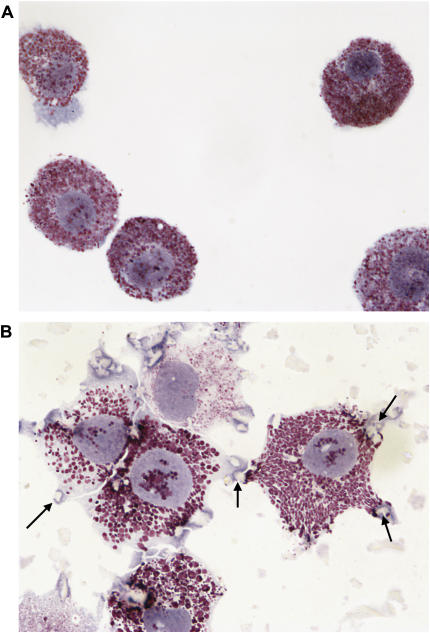

A series of experiments was then initiated to determine the effects of silica on cultured mast cells. At the start of these experiments, BMMC were visually examined after exposure to silica for 24 h. An apparent internalization of silica particles was observed (see Figures 3A and 3B). This was not unexpected, as mast cells are known to be phagocytic and macrophages similarly internalize silica (13, 14).

Figure 3.

Silica interacts with and is internalized by BMMC. Images of (A) untreated or (B) BMMC exposed to 25 μg/cm2 silica for 24 h and stained with Wright-Giemsa (magnification: ×100). Arrows indicate silica particles.

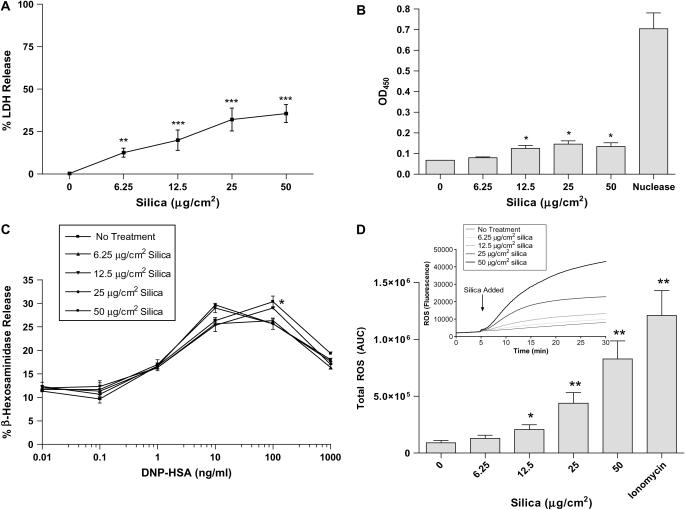

Silica exposure has been reported to induce cytotoxicity (apoptosis and necrosis) in alveolar macrophages and thus contribute to tissue inflammation (15–18). As shown in Figure 4A, silica did induce between 5 and 15% LDH release from BMMC exposed to 6.25 μg/cm2 silica, and at 50 μg/cm2 silica, between 20 and 40% LDH release was observed. To further examine the ability of silica to affect viability of BMMC, the TUNEL assay was also employed. Figure 4B shows a dose-dependent increase in cells staining positive for DNA fragmentation as determined by an in vitro TUNEL assay. Significant differences between untreated BMMC and 12.5, 25, and 50 μg/cm2 silica were seen 24 h after exposure (Figure 4B, P ⩽ 0.05). Consistent with LDH release (Figure 4A), silica induces apoptosis in BMMC at higher doses. However, by either assay, a majority of the cells remained viable 24 h after silica exposure.

Figure 4.

Silica induces LDH release, apoptosis, and ROS production, but has little effect on β-hexosaminidase release in BMMC. (A) LDH release was measured in supernatant of silica-exposed BMMC. (B) Apoptosis was determined by DNA fragmentation in BMMC (1 × 105/well) exposed to 0, 6.25, 12.5, 25, or 50 μg/cm2 silica for 24 h. (C) FcεRI-mediated β-hexosaminidase release, as a measure of degranulation, was determined 24 h after exposure of BMMC (50,000/well) to 0, 6.25, 12.5, 25, or 50 μg/cm2 silica. (D) ROS production in silica-exposed BMMC where silica was added to BMMC 5 min after addition of the fluorescent probe DCF, at doses of 0, 6.25, 12.5, 25, or 50 μg/cm2. Intracellular ROS production was measured up to 30 min (insert in D). Area under the curve of silica-induced ROS production with ionomycin as a positive control (D). Data are means ± SEM for three experiments. *P ⩽ 0.05, **P ⩽ 0.01, and ***P ⩽ 0.001 as compared with untreated BMMC.

Silica exposure was next examined for the ability to alter FcεRI-mediated degranulation of BMMC as one mechanism by which silica might enhance inflammation mediated by mast cells. Pretreatment of BMMC (sensitized with mouse IgE anti-DNP) with silica at doses of 6.25, 25, and 50 μg/cm2 minimally decreased β-hexosaminidase release after addition of increasing amounts of DNP-HSA compared with BMMC that were not exposed to silica (Figure 4C). Silica exposure by itself similarly did not induce β-hexosaminidase release from mouse BMMC (data not shown). These results reveal that silica has little indirect effect on FcεRI-mediated mast cell degranulation, nor does silica directly induce degranulation.

Silica Induces Production of Reactive Oxygen Species in BMMC

Silica exposure induces the production of ROS in macrophages and has been implicated in mediating biological effects such as fibrosis after silica exposure (19). Therefore, the ability of mast cells to produce ROS after silica exposure was assessed. Figure 4D (insert) shows that induction of ROS occurs rapidly and is sustained after addition of silica. Total ROS production measured as area under the curve in silica-exposed BMMC was significantly increased after exposure to 12.5, 25, and 50 μg/cm2 silica compared with untreated BMMC (Figure 4D).

Silica Induces Cytokine and Chemokine Production and Enhances IgE-Mediated Cytokine and Chemokine Production in BMMC

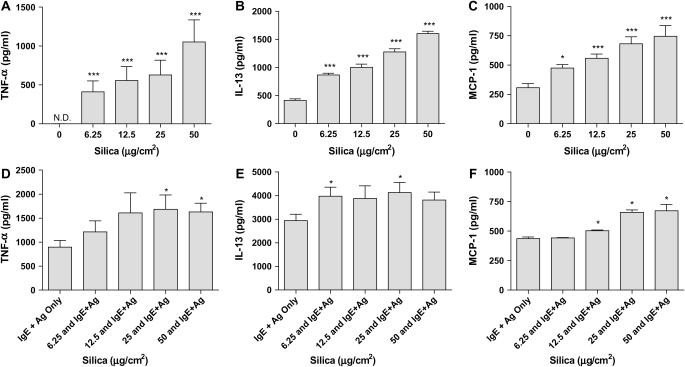

Silicosis has been associated with increased production of profibrotic cytokines and chemokines in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, including TNF-α, IL-13, and MCP-1 (CCL2) (20–22). Therefore, the ability of silica to directly induce production of such mediators from BMMC, as well as the ability of silica to enhance FcεRI-mediated cytokine and chemokine production, was explored. After 24 h of silica exposure, the production of TNF-α, IL-13, and MCP-1 by BMMC are dose-dependently increased (Figures 5A–5C, respectively). Silica-exposed BMMC that were sensitized with IgE anti-DNP and challenged with DNP-HSA for 8 h showed enhanced production of TNF-α, IL-13, and MCP-1 (Figures 5D–5F).

Figure 5.

Silica directs TNF-α, IL-13, and MCP-1 production and enhances FcεRI-mediated production of these mediators in BMMC. BMMC (2 × 105/well) were exposed to 0, 6.25, 12.5, 25, or 50 μg/cm2 silica for 24 h before the measurement of TNF-α (A), IL-13 (B), and MCP-1 (C). In addition, BMMC sensitized with IgE anti-DNP and exposed overnight to 0, 6.25, 12.5, 25, or 50 μg/cm2 silica before challenge with DNP-HSA for 8 h were measured for production of TNF-α (D), IL-13 (E), and MCP-1 (F). Data are means ± SEM for three independent experiments. *P ⩽ 0.05 and ***P ⩽ 0.001 as compared with untreated BMMC.

In addition to cytokine production, protease activity was measured in the supernatant of silica-exposed BMMC. The overall protease activity within the supernatant from BMMC exposed to silica at doses of 12.5, 25, and 50 μg/cm2 for 24 h was significantly increased as compared with untreated BMMC (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Silica induces release of proteases from BMMC. Protease activity was measured in supernatants of BMMC exposed to 0, 6.25, 12.5, 25, or 50 μg/cm2 silica for 24 h. Data are means ± SEM for three independent experiments. *P ⩽ 0.05 and ***P ⩽ 0.001 as compared with untreated BMMC.

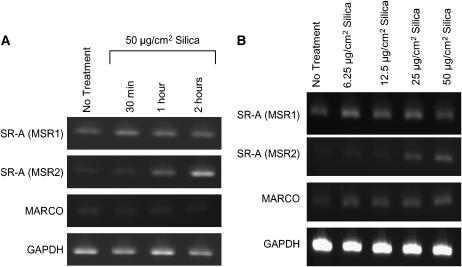

Mast Cells Express Scavenger Receptors: Apoptosis and ROS Production Is Reduced in SR-A–, MARCO–, and SR-A/MARCO–Deficient BMMC

Silica has been reported in part to mediate effects through SR-A on macrophages (15, 16). To determine if mast cells also express scavenger receptors, we examined these cells for the presence of mRNA for these receptors. Figure 7 demonstrates mRNA expression for two closely related scavenger receptors, SR-A I/II and MARCO, both before and after silica exposure in BMMC. While mRNA for SR-A II (MSR2) was increased after silica exposure over a time course, all scavenger receptors appeared to increase by 2 h after silica exposure ranging from 6.25–50 μg/cm2 (Figures 7A and 7B). Because of this evidence that mast cells express scavenger receptors, experiments were entered into examining the effects of silica on mast cells cultured from scavenger receptor KO mice.

Figure 7.

Demonstration that BMMC express mRNA for SR-A (MSR1 and MSR2) and MARCO. (A) BMMC (1 × 106 cells/condition) were examined for mRNA expression of SR-A and MARCO in untreated or BMMC exposed to 50 μg/cm2 silica for 30 min, 1 h, or 2 h. (B) In addition, mRNA for SR-A and MARCO were examined in BMMC at 2 h after addition of 0, 6.25, 12.5, 25, or 50 μg/cm2 silica. GAPDH was used as a control for constitutive gene expression. Results are representative examples of three separate experiments.

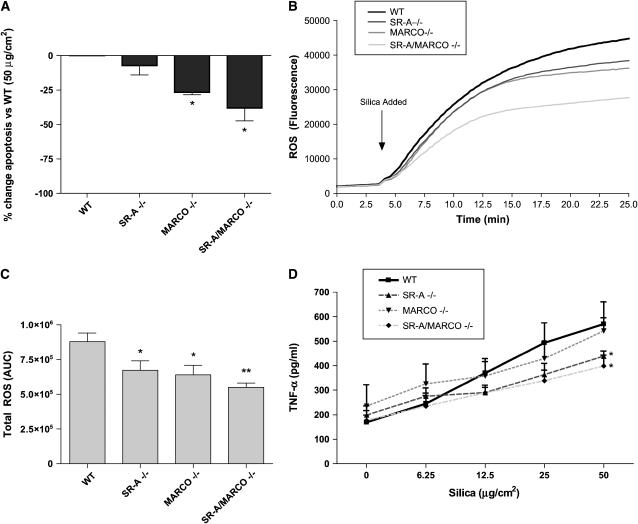

As shown earlier (Figure 4B), silica exposure at 50 μg/cm2 induces DNA fragmentation as compared with untreated cells. Therefore, the induction of apoptosis by silica in BMMC derived from SR-A I/II KO, MARCO KO, and SR-A/MARCO double KO mice was examined. As shown in Figure 8A, there was a significant decrease in the level of DNA fragmentation in silica-exposed BMMC from MARCO KO and SR-A/MARCO double KO mice when compared with silica-exposed BMMC from C57Bl/6 mice. ROS production in BMMC from SR-A KO, MARCO KO, and SR-A/MARCO double KO mice was similarly less compared with ROS production by BMMC from C57Bl/6 controls after exposure to 50 μg/cm2 silica (Figures 8B and 8C). These results indicate that scavenger receptors are able to mediate in part the apoptotic state of BMMC, as well as ROS production, in response to silica.

Figure 8.

Apoptosis, ROS, and TNF-α production are reduced in silica exposed BMMC cultured from SR-AI/II KO, MARCO KO, or SR-A/MARCO double KO mice. (A) DNA fragmentation was measured in BMMC obtained from scavenger receptor KO mice and exposed to 50 μg/cm2 silica for 24 h. Data are presented as the percentage decrease in OD values as compared with C57Bl/6 WT BMMC exposed to 50 μg/cm2 silica. (B) ROS production using the fluorescent probe DCF, following exposure to 50 μg/cm2 silica in SR-A KO, MARCO KO and SR-A/MARCO double KO BMMC is shown over 25 min. (C) ROS production was also analyzed as AUC in BMMC from scavenger receptor KO and WT mice exposed to 50 μg/cm2 silica. (D) TNF-α production measured by ELISA is shown 24 h after addition of 50 μg/cm2 silica in SR-A KO, MARCO KO, and SR-A/MARCO double KO BMMC (silica doses presented in a linear form for representation only). Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 3). *P ⩽ 0.05 and **P ⩽ 0.01 as compared with wild-type BMMC exposed to the same dose of silica.

TNF-α Production Is Altered in Silica-Exposed BMMC from SR-A– and MARCO–Deficient Mice

Due to the changes in apoptosis and redox states observed in SR-A– and MARCO–deficient BMMC after silica exposure, the role of these scavenger receptors in mediating TNF-α production after silica exposure was examined. Figure 8D shows a role for SR-A in enhancing cytokine production after silica exposure. TNF-α is significantly decreased after 50 μg/cm2 silica exposure in the SR-A KO and SR-A/MARCO double KO BMMC as compared with WT BMMC exposed to the same dose of silica (Figure 8D, P ⩽ 0.01).

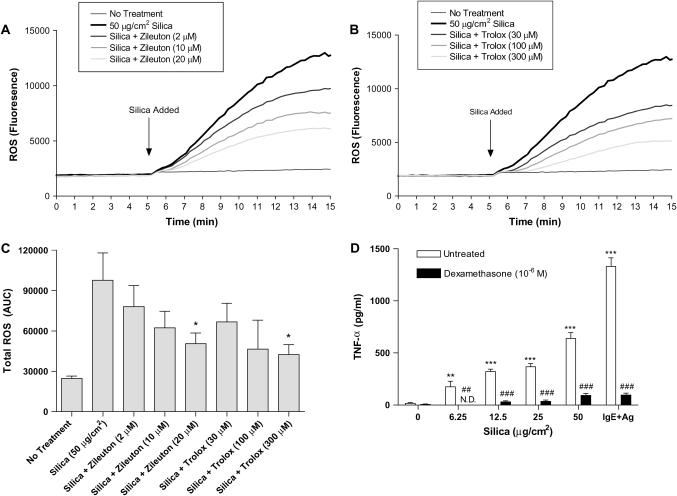

Treatment of BMMC with Zileuton, Trolox, and Dexamethasone Reduced Silica-Directed Mast Cell Activation

There is currently no effective treatment for silicosis; however, steroids and anti-inflammatory agents have been used in an attempt to control symptoms and the progression of disease. Using anti-inflammatory and antioxidant compounds, the ability of these agents to inhibit silica-directed mast cell activation in vitro was examined. Using the 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor Zileuton (Figure 9A), or the vitamin E derivative Trolox (Figure 9B), we were able to significantly reduce ROS levels in BMMC after silica exposure. Figure 9C shows total area under the curve for the blockade of ROS using both Zileuton and Trolox. Measured as AUC, Zileuton added at 20 μM to BMMC immediately before the addition of silica significantly inhibited ROS formation as compared with BMMC treated with 50 μg/cm2 silica (Figure 9C). Also, the addition of 300 μM Trolox to BMMC before the addition of silica significantly reduced ROS levels as compared with BMMC treated with 50 μg/cm2 silica (Figure 9C).

Figure 9.

Treatment of silica exposed BMMC with Zileuton and Trolox reduces ROS formation and treatment with dexamethasone inhibits silica-directed TNF-α production. (A) Zileuton, a 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor, was added to BMMC at concentrations of 2, 10, and 20 μM 5 min before addition of 50 μg/cm2 silica to inhibit ROS formation. (B) In addition, the vitamin E derivative Trolox was added at concentrations of 30, 100, and 300 μM 5 min before addition of 50 μg/cm2 silica to inhibit intracellular ROS formation. (C) Area under the curve was calculated for the reduction of silica-induced ROS formation using Zileuton and Trolox. (D) TNF-α was measured in BMMC (2 × 105/well) that were treated with dexamethasone (10−6 M) 1 h before the addition of 50 μg/cm2 silica for 24 h. BMMC that were sensitized overnight with IgE anti-DNP and challenged for 8 h with 100 ng/ml DNP-HSA were used as a control for the inhibition of TNF-α production by dexamethasone. Data are means ± SEM for three independent experiments. *P ⩽ 0.05, **P ⩽ 0.01, and ***P ⩽ 0.001 as compared with silica-exposed BMMC not treated with either Zileuton, Trolox, or dexamethasone. ##P ⩽ 0.01 and ###P ⩽ 0.001, silica-exposed BMMC treated with dexamethasone as compared with silica-exposed BMMC.

BMMC that were treated with dexamethasone for 1 h before the addition of silica significantly inhibited TNF-α production (Figure 9D). As previously shown, silica dose-dependently increased TNF-α production from BMMC 24 h after exposure; however, using dexamethasone, silica-induced TNF-α production at all doses of silica was abrogated (Figure 9D). As a control, dexamethasone was also used to inhibit FcεRI-mediated TNF-α production from BMMC (Figure 9D). Although similar treatments have been attempted in patients with silicosis, these data suggest that silica-directed mast cell activation could be inhibited using a combination of clinically relevant anti-inflammatory compounds.

DISCUSSION

A role for mast cells in silica-induced pulmonary inflammation has been suggested; however, possible mechanisms in this process have not been explored (3, 4, 23). In this article we demonstrate that B6.Cg-kitW-sh mast cell–deficient mice did not develop silicosis, including significant collagen deposition, 3 mo after silica exposure. Further in vitro experiments on the effects of silica on mast cells suggest that one reason may be that silica has the ability to directly activate mast cells, a process in part dependent on scavenger receptors, here shown for the first time to be expressed on mast cells. Thus, silica-exposed mast cells produced cytokines, generated ROS, and released proteolytic activity.

Mast cells have been implicated in the development of pulmonary inflammation 2 wk after exposure to silica in that WBB6F1-W/Wv mast cell–deficient mice were relatively protected from acute exposure to silica compared with wild-type mice (23). Because responses were examined 14 d after silica exposure, inflammation, but not the development of fibrosis, could be determined (23). Thus wild-type mice exhibited lung infiltrates, an increase in lung mast cells, and neutrophilia in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (23). Lung lesions and neutrophilia were less pronounced in W/Wv mice (23). A problem in concluding mast cells were important to the evolution of inflammation after silica exposure in W/Wv mice is that mast cell deficiency in W/Wv mice is accompanied by some immune deficits and by thrombocytopenia (24).

These latter concerns have led us to use a second and more recent mast cell–deficient mouse model, employing sash mice (B6.Cg-kitW-sh) to examine effects of silica exposure on pulmonary tissues. We also chose to examine the chronic rather than acute response to silica so we could also determine chronic effects of the inflammatory response, including the development of fibrosis. We found that in B6.Cg-kitW-sh mast cell–deficient mice, both inflammation and collagen deposition were minimal 3 mo after silica instillation (Figures 1 and 2). However, wild-type mice developed pathology which resembled that seen in patients with silicosis, including formation of silicotic lesions and collagen deposition. Future experiments, as possible given the duration of this protocol, will attempt to examine the ability to restore the silicosis response in mast cell–deficient mice through reconstitution of lung mast cells. For now, we focused our attention to how silica could directly alter mast cell biology.

Silica has been reported to induce apoptosis of alveolar macrophages and a dysregulation of apoptosis due to silica exposure has been implicated in disease processes including inflammation, fibrosis and autoimmunity (8, 25–30). For example, in vivo treatment of silica-exposed mice with caspase inhibitors has been reported to significantly inhibit neutrophil accumulation and alleviate pulmonary inflammation (27). While internalization of silica in BMMC was observed, the majority of BMMC did remain viable 24 h after silica exposure as measured by LDH release and DNA fragmentation (Figures 4A and 4B). Although these data do suggest that some silica effects on mast cells and inflammation may occur via apoptosis, since the majority of BMMC remain viable, silica-exposed BMMC could well contribute to inflammation by additional mechanisms requiring responsive cells.

Other environmental contaminants, such as certain heavy metals, have been reported to enhance FcεRI-mediated mast cell degranulation, a mast cell response associated with allergic disease (31). Therefore, the ability of silica to alter IgE-dependent BMMC degranulation was assessed. As Figure 4C demonstrates, silica had little effect on FcεRI-mediated degranulation. Silica by itself did not induce BMMC degranulation.

Silica has been reported to induce ROS in alveolar macrophages, and this in turn has been reported to enhance inflammation (19, 21, 32, 33). In this study, silica exposure dose-dependently induced ROS production in BMMC. This induction was rapid and sustained (Figure 4D). However, in this study ROS production was largely intracellular. Thus, it seems plausible that silica-induced ROS by mast cells is not contributing significantly to tissue damage.

One probable mechanism for mast cell involvement in silicosis is through alteration of cytokine or chemokine levels within the lung. Therefore, the ability of silica to induce TNF-α, IL-13, and MCP-1, all reported to be major contributors to the development of pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis, was examined (21, 22, 26, 34–38). Figure 5 demonstrates that silica exposure dose-dependently increased TNF-α, IL-13, and MCP-1. These mediators contribute to inflammation through the recruitment of additional inflammatory cells such as neutrophils or lymphocytes (39). In addition, TNF receptor KO mice have been reported to have impaired responses to silica exposure, including development of silicosis which has been attributed to alterations in chemokine levels, including MCP-1 (32, 38, 40). IL-13 has been studied extensively as a major contributor to the development of pulmonary fibrosis in several different models (35, 37, 41–43). Mouse BMMC produced significant quantities of IL-13 after silica exposure and may represent a major source of IL-13 in silica-induced pulmonary inflammation.

The ability of silica to alter FcεRI-mediated cytokine production was also assessed (Figure 5). BMMC exposed to silica for 24 h before stimulation via FcεRI aggregation–enhanced production of TNF-α, IL-13, and MCP-1 as compared with BMMC stimulated via FcεRI but not exposed to silica. However, these effects appear to be no more than additive and therefore silica exposure does not appear to alter FcεRI-mediated signaling events, consistent with results examining degranulation.

In addition to cytokine production, an increase in the protease activity was measured within the supernatant of silica-exposed BMMC (Figure 6). The production of mast cell proteases may be another important mechanism in the development of silicosis since mast cell chymase has been reported to be involved in a bleomycin-induced model of pulmonary fibrosis by mediating the cleavage of TGF-β1 to its active form (44). In addition to chymase, mast cell tryptase has been reported to be involved in activation of fibroblasts and stimulation of collagen production (45–47).

The recognition of silica by macrophages and their subsequent activation has been reported to occur via scavenger receptors (15, 16, 48, 49). The expression of, and a functional role for, these scavenger receptors has not been reported when considering mast cells. Therefore, mRNA expression of SR-A on BMMC, as well as a closely related receptor, MARCO, was first examined. Figure 6 shows mRNA for scavenger receptors in BMMC and that silica exposure increased mRNA levels for SR-A II (MSR2) within 2 h. Thus BMMC had mRNA for both SR-A I (MSR1) and MARCO; however, only SR-A II message appeared to increase after silica exposure.

We were thus able to use BMMC from mice deficient in SR-A I/II, MARCO, or both, to demonstrate that these receptors modulate some of the effects of silica on mast cells (Figure 7). Apoptosis, ROS, and TNF-α production were decreased in MARCO KO and SR-A/MARCO double KO BMMC after silica exposure. In contrast to other reports, it appears that MARCO is playing a more prominent role in enhancing cellular responses to silica in mast cells compared with SR-A I/II (15, 16, 48). This is consistent with reports that MARCO is more important in binding of TiO2 and unopsonized bacteria in alveolar macrophages than is SR-A I/II (6, 50). These data demonstrate that scavenger receptors enhance the response to silica in BMMC. Whether additional scavenger receptors not yet identified are also involved remains a possibility.

Finally, the ability to inhibit silica-directed mast cell activation was examined using several anti-inflammatory and antioxidant compounds including Zileuton (5-lipoxygenase inhibitor), Trolox (vitamin E derivative), and dexamethasone. Both Zileuton and Trolox were able to reduce ROS formation in BMMC after silica exposure, and dexamethasone was able to significantly inhibit silica-directed TNF-α production from BMMC (Figure 9). Although similar treatments have been explored for silicosis, they have largely not been effective because the disease is not detected until late stages. However, these data suggest that several clinically relevant compounds that in part target mast cells may be beneficial in the treatment of silicosis if the disease was detected early.

In total, the data presented demonstrate that silica can direct mast cell activation leading to production of inflammatory mediators, and that these responses are enhanced by mast cell scavenger receptors. Through this process, mast cells appear to have a significant role in the recruitment of inflammatory cells leading to the development of silicosis. Taken together, these data provide evidence that treatment of silicosis and possibly other particle-induced inflammatory conditions should explore the mast cell as an important therapeutic target.

This work was supported by NIH intramural funds, NIH R01/ES04804 and COBRE P20RR01760.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0197OC on August 10, 2006

Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.American thoracic society committee of the scientific assembly on environmental and occupational health. Adverse effects of crystalline silica exposure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997;155:761–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bang KM, Mazurek JM, Attfield MD. Silicosis mortality, prevention, and control–United States, 1968–2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2005;54:401–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kopinski P, Czunko P, Soja J, Lackowska B, Gil K, Jedynak U, Szczeklik J, Sladek K, Chlap Z. Pneumonol Alergol Pol 2000;68:109–119. (cytoimmunologic changes in material obtained from bronchoalveolar lavage (bal) in asymptomatic individuals chronically exposed to silica dust). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamada H, Vallyathan V, Cool CD, Barker E, Inoue Y, Newman LS. Mast cell basic fibroblast growth factor in silicosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161:2026–2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suzuki H, Kurihara Y, Takeya M, Kamada N, Kataoka M, Jishage K, Ueda O, Sakaguchi H, Higashi T, Suzuki T, et al. A role for macrophage scavenger receptors in atherosclerosis and susceptibility to infection. Nature 1997;386:292–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arredouani M, Yang Z, Ning Y, Qin G, Soininen R, Tryggvason K, Kobzik L. The scavenger receptor marco is required for lung defense against pneumococcal pneumonia and inhaled particles. J Exp Med 2004;200:267–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Babaev VR, Gleaves LA, Carter KJ, Suzuki H, Kodama T, Fazio S, Linton MF. Reduced atherosclerotic lesions in mice deficient for total or macrophage-specific expression of scavenger receptor-a. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2000;20:2593–2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown JM, Archer AJ, Pfau JC, Holian A. Silica accelerated systemic autoimmune disease in lupus-prone new zealand mixed mice. Clin Exp Immunol 2003;131:415–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Decker T, Lohmann-Matthes ML. A quick and simple method for the quantitation of lactate dehydrogenase release in measurements of cellular cytotoxicity and tumor necrosis factor (tnf) activity. J Immunol Methods 1988;115:61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown JM, Schwanke CM, Pershouse MA, Pfau JC, Holian A. Effects of rottlerin on silica-exacerbated systemic autoimmune disease in new zealand mixed mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2005;289: L990–L998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwaki S, Tkaczyk C, Satterthwaite AB, Halcomb K, Beaven MA, Metcalfe DD, Gilfillan AM. Btk plays a crucial role in the amplification of fc epsilonri-mediated mast cell activation by kit. J Biol Chem 2005;280: 40261–40270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keston AS, Brandt R. The fluorometric analysis of ultramicro quantities of hydrogen peroxide. Anal Biochem 1965;11:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stringer B, Imrich A, Kobzik L. Flow cytometric assay of lung macrophage uptake of environmental particulates. Cytometry 1995;20:23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malaviya R, Abraham SN. Mast cell modulation of immune responses to bacteria. Immunol Rev 2001;179:16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chao SK, Hamilton RF, Pfau JC, Holian A. Cell surface regulation of silica-induced apoptosis by the sr-a scavenger receptor in a murine lung macrophage cell line (mh-s). Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2001;174:10–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamilton RF, de Villiers WJ, Holian A. Class a type ii scavenger receptor mediates silica-induced apoptosis in chinese hamster ovary cell line. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2000;162:100–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thibodeau M, Giardina C, Hubbard AK. Silica-induced caspase activation in mouse alveolar macrophages is dependent upon mitochondrial integrity and aspartic proteolysis. Toxicol Sci 2003;76:91–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thibodeau MS, Giardina C, Knecht DA, Helble J, Hubbard AK. Silica-induced apoptosis in mouse alveolar macrophages is initiated by lysosomal enzyme activity. Toxicol Sci 2004;80:34–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fubini B, Hubbard A. Reactive oxygen species (ros) and reactive nitrogen species (rns) generation by silica in inflammation and fibrosis. Free Radic Biol Med 2003;34:1507–1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barbarin V, Xing Z, Delos M, Lison D, Huaux F. Pulmonary overexpression of il-10 augments lung fibrosis and th2 responses induced by silica particles. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2005;288:L841–L848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rimal B, Greenberg AK, Rom WN. Basic pathogenetic mechanisms in silicosis: current understanding. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2005;11:169–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rose CE Jr, Sung SS, Fu SM. Significant involvement of ccl2 (mcp-1) in inflammatory disorders of the lung. Microcirculation 2003;10:273–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suzuki N, Horiuchi T, Ohta K, Yamaguchi M, Ueda T, Takizawa H, Hirai K, Shiga J, Ito K, Miyamoto T. Mast cells are essential for the full development of silica-induced pulmonary inflammation: a study with mast cell-deficient mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1993;9:475–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grimbaldeston MA, Chen CC, Piliponsky AM, Tsai M, Tam SY, Galli SJ. Mast cell-deficient w-sash c-kit mutant kit w-sh/w-sh mice as a model for investigating mast cell biology in vivo. Am J Pathol 2005;167: 835–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pfau JC, Brown JM, Holian A. Silica-exposed mice generate autoantibodies to apoptotic cells. Toxicology 2004;195:167–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borges VM, Falcao H, Leite-Junior JH, Alvim L, Teixeira GP, Russo M, Nobrega AF, Lopes MF, Rocco PM, Davidson WF, et al. Fas ligand triggers pulmonary silicosis. J Exp Med 2001;194:155–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borges VM, Lopes MF, Falcao H, Leite-Junior JH, Rocco PR, Davidson WF, Linden R, Zin WA, DosReis GA. Apoptosis underlies immunopathogenic mechanisms in acute silicosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2002;27:78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCabe MJ Jr. Mechanisms and consequences of silica-induced apoptosis. Toxicol Sci 2003;76:1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takata-Tomokuni A, Ueki A, Shiwa M, Isozaki Y, Hatayama T, Katsuyama H, Hyodoh F, Fujimoto W, Ueki H, Kusaka M, et al. Detection, epitope-mapping and function of anti-fas autoantibody in patients with silicosis. Immunology 2005;116:21–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang L, Bowman L, Lu Y, Rojanasakul Y, Mercer RR, Castranova V, Ding M. Essential role of p53 in silica-induced apoptosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2005;288:L488–L496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walczak-Drzewiecka A, Wyczolkowska J, Dastych J. Environmentally relevant metal and transition metal ions enhance fc epsilon ri-mediated mast cell activation. Environ Health Perspect 2003;111:708–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barrett EG, Johnston C, Oberdorster G, Finkelstein JN. Antioxidant treatment attenuates cytokine and chemokine levels in murine macrophages following silica exposure. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1999;158:211–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singal M, Finkelstein JN. Amorphous silica particles promote inflammatory gene expression through the redox sensitive transcription factor, ap-1, in alveolar epithelial cells. Exp Lung Res 2005;31:581–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee CG, Homer RJ, Zhu Z, Lanone S, Wang X, Koteliansky V, Shipley JM, Gotwals P, Noble P, Chen Q, et al. Interleukin-13 induces tissue fibrosis by selectively stimulating and activating transforming growth factor beta(1). J Exp Med 2001;194:809–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wynn TA. Il-13 effector functions. Annu Rev Immunol 2003;21:425–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Piguet PF, Collart MA, Grau GE, Sappino AP, Vassalli P. Requirement of tumour necrosis factor for development of silica-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Nature 1990;344:245–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matsushita M, Yamamoto T, Nishioka K. Upregulation of interleukin-13 and its receptor in a murine model of bleomycin-induced scleroderma. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2004;135:348–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Okuma T, Terasaki Y, Kaikita K, Kobayashi H, Kuziel WA, Kawasuji M, Takeya M. C-c chemokine receptor 2 (ccr2) deficiency improves bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis by attenuation of both macrophage infiltration and production of macrophage-derived matrix metalloproteinases. J Pathol 2004;204:594–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu Z, Ma B, Zheng T, Homer RJ, Lee CG, Charo IF, Noble P, Elias JA. Il-13-induced chemokine responses in the lung: role of ccr2 in the pathogenesis of il-13-induced inflammation and remodeling. J Immunol 2002;168:2953–2962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pryhuber GS, Huyck HL, Baggs R, Oberdorster G, Finkelstein JN. Induction of chemokines by low-dose intratracheal silica is reduced in tnfr i (p55) null mice. Toxicol Sci 2003;72:150–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jakubzick C, Kunkel SL, Puri RK, Hogaboam CM. Therapeutic targeting of il-4- and il-13-responsive cells in pulmonary fibrosis. Immunol Res 2004;30:339–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kolodsick JE, Toews GB, Jakubzick C, Hogaboam C, Moore TA, McKenzie A, Wilke CA, Chrisman CJ, Moore BB. Protection from fluorescein isothiocyanate-induced fibrosis in il-13-deficient, but not il-4-deficient, mice results from impaired collagen synthesis by fibroblasts. J Immunol 2004;172:4068–4076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Misson P, van den Brule S, Barbarin V, Lison D, Huaux F. Markers of macrophage differentiation in experimental silicosis. J Leukoc Biol 2004;76:926–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tomimori Y, Muto T, Saito K, Tanaka T, Maruoka H, Sumida M, Fukami H, Fukuda Y. Involvement of mast cell chymase in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Eur J Pharmacol 2003;478:179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cairns JA, Walls AF. Mast cell tryptase stimulates the synthesis of type i collagen in human lung fibroblasts. J Clin Invest 1997;99:1313–1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levi-Schaffer F, Piliponsky AM. Tryptase, a novel link between allergic inflammation and fibrosis. Trends Immunol 2003;24:158–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abe M, Kurosawa M, Ishikawa O, Miyachi Y, Kido H. Mast cell tryptase stimulates both human dermal fibroblast proliferation and type i collagen production. Clin Exp Allergy 1998;28:1509–1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Iyer R, Hamilton RF, Li L, Holian A. Silica-induced apoptosis mediated via scavenger receptor in human alveolar macrophages. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1996;141:84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kobzik L. Lung macrophage uptake of unopsonized environmental particulates. Role of scavenger-type receptors. J Immunol 1995;155:367–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Palecanda A, Paulauskis J, Al-Mutairi E, Imrich A, Qin G, Suzuki H, Kodama T, Tryggvason K, Koziel H, Kobzik L. Role of the scavenger receptor marco in alveolar macrophage binding of unopsonized environmental particles. J Exp Med 1999;189:1497–1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]