Abstract

Particulate air pollution is linked to increased pneumonia epidemiologically and diminished lung bacterial clearance experimentally. We investigated the effect of concentrated ambient particles (CAPs, ⩽ PM2.5) on the interaction of murine primary alveolar macrophages (AMs) and the murine macrophage cell line, J774 A.1, with Streptococcus pneumoniae. We found that CAPs increased binding of bacteria by both primary AMs and J774 cells (66.7 ± 10.6% and 58.9 ± 4.0%, respectively, n = 4). In contrast to bacterial binding, CAPs decreased internalization in both AMs and J774 (55.4 ± 8.5% and 54.7 ± 5.1%, respectively, n = 4). The rate of killing of internalized bacteria was similar, but CAPs caused a decrease in the absolute number of bacteria killed by macrophages, mainly due to decreased internalization. Additional analyses showed that soluble components of CAPs mediated the enhanced binding and decreased internalization of S. pneumoniae. Chelation of iron in soluble CAPs substantially reversed, while addition of iron as ferric ammonium citrate restored inhibition of phagocytosis of S. pneumoniae in vitro. The results identify phagocytic internalization as a specific target for toxic effects of air pollution particles on AMs.

Keywords: concentrated ambient particles, macrophages, Streptococcus pneumoniae, phagocytosis, killing

CLINICAL RELEVANCE

The data identify details of how air pollution particles reduce lung macrophage antibacterial function. This may lead to therapies to protect people from the increased risk of pneumonia that is linked to particulate air pollution.

Numerous epidemiologic studies have demonstrated a significant association between elevated levels of air pollution and increased risk of mortality and morbidity (1–4), especially in people with pre-existing pulmonary disease (2, 3, 5). Infection, specifically pneumonia, contributes substantially to morbidity among elderly individuals exposed to ambient particulate matter (PM), as illustrated by the increased pneumonia hospital admissions associated with increased air particle levels (6, 7). These epidemiologic findings suggest that airborne particulates may act as an immunosuppressive factor that can undermine the normal pulmonary defenses. Since elderly individuals with chronic respiratory disease are not only at increased risk of pneumonia but also are less likely to recover from infections (8), alterations in the lung innate defenses may play a role in the observed increase in mortality after PM episodes.

The mechanisms by which particles diminish resistance to infection have not been fully elucidated (9), but are likely to include an important role for the alveolar macrophage (AM). The AM stands as the guardian of the alveolar–blood interface, serving as the front line of cellular defense against respiratory pathogens (10). The AM is the primary cell responsible for uptake and clearance of inhaled microorganisms and environmental particles (11–13). AM interaction with air pollution particles results in particle phagocytosis, oxidant production (14), and release of inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α (15) and macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-2 (16).

Prior studies show that exposure to air pollution particles can increase susceptibility to lung infection. For instance, Hatch and coworkers tested various particles that increased susceptibility to pulmonary bacterial infection in a mouse model (17). Diesel exhaust particles (DEP) can impair the pulmonary clearance of Listeria monocytogenes in rats (18), and increase the severity of influenza virus infection in mice (19). Exposure of rats to residual oil fly ash (ROFA) significantly enhanced lung injury and delayed the pulmonary clearance of L. monocytogenes along with a reduction in nitric oxide production by AMs (20).

While epidemiologic data reveal increased hospital admissions and so on related to lung infection, which organism(s) causes the increase is unknown. One likely candidate is Streptococcus pneumoniae, the most frequent bacterial pathogen causing pneumonia in humans (21). Host defenses against pneumococcal pneumonia are complex and remarkably efficient, given the much greater rate of colonization of upper airways by pneumococci than pneumonic infection and the normal nocturnal aspiration of small amounts of bacteria-laden nasopharyngeal secretions (22, 23). The lung macrophage plays a critical role in the initial host defense against bacterial infection (24, 25), and is a likely target for air particle-mediated disruption of innate resistance. Hence, the purpose of this study was to investigate in vitro the effects of concentrated ambient particles (CAPs) on macrophage phagocytosis and killing of S. pneumoniae.

We analyzed AM binding, ingestion, and killing of S. pneumoniae. Because our previous studies found that activated or “primed” AMs showed enhanced responses to air particles (26), we compared the effects of CAPs on IFN-γ–primed and normal AMs, as well as the macrophage cell line J774A.1. We also investigated which components of CAPs samples altered macrophage function, and studied the contribution of oxidant mechanisms by use of antioxidants and metal chelation. The results show that soluble metals in CAPs cause oxidant-dependent and specific inhibition of macrophage internalization of bacteria, which results in overall diminished bacterial killing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Male BALB/c mice (age 6–8 wk) were purchased from the Charles River Laboratories Inc. (Wilmington, MA) and maintained under specific pathogen–free conditions. All protocols used in these experiments were approved by Harvard University's animal care and use committee. The mice were killed with an intraperitoneal injection of a lethal dose of sodium pentobarbital (FatalPlus; Vortech Pharmaceuticals, Dearborn, MI).

Cell Isolation and Culture

AMs were isolated by repeated bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) with PBS. For primed AMs, mice were pretreated with 20,000 U/ml of IFN-γ (PeproTech Inc., Rocky Hill, NJ) or PBS by aerosol administration for 15 min. After 3 h treatment, AMs were isolated by BAL. AMs were centrifuged at 250 × g and resuspended in a balanced salt solution (BSS+) containing NaCl (124 mM), KCl (5.8 mM), dextrose (10 mM), and HEPES (20 mM), adding CaCl2 (0.3 mM) and MgCl2 (1.0 mM). Cells were cytocentrifuged onto glass slides and stained with Diff-Quik (Baxter, Miami, FL), a modified Wright-Giemsa stain for differential counts. The normal samples used were routinely comprised of > 95% AMs.

The murine macrophage cell line J774A.1 (American Type Culture Collection [ATCC], Manassas, VA) was grown in RPMI 1640 medium (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, L-glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). The cells were cultured in a 6-well ultra-low adherent plate (Corning Inc., Corning, NY) at 2 × 105/ml for 24−48 h before the assay. Cell counts and viability were determined using a hemocytometer and trypan blue dye exclusion. Cells were then adjusted to 1 × 106 cells/ml in BSS+ for experimental use.

Bacteria

Encapsulated virulent S. pneumoniae strain ATCC6303 (Serotype 3) was grown for 4 h to midlogarithmic phase (OD600 reaches ca. 0.3–0.4) at 37°C using Todd Hewitt Broth supplemented with 0.5% yeast extract (Difco, Detroit, MI). Bacteria were harvested by centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C and washed twice with sterile ice-cold PBS. Bacteria were then resuspended in sterile PBS at a concentration of about 2.5–5 × 106 colony-forming units (cfu)/20 μl, which was confirmed by plating out 10-fold series dilutions onto sheep blood-agar plates. Twenty microliters of bacterial suspension was added to macrophages.

Preparation of Particle Suspensions

Concentrated air particles (CAPs, 0.1−2.5 μM diameter, PM2.5) were collected from Boston air using the Harvard concentrator (27). At least three different CAPs samples collected on different days were studied. Urban air particle sample SRM 1649 (UAP) was collected in Washington, D.C. and was purchased from the National Bureau of Standards (Washington, D.C.). Titanium dioxide (TiO2) was obtained from Baker Chemicals (Phillipsburg, NJ). Carbon black (CB) was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Suspensions of CAPs, UAP, TiO2, and CB were prepared in H2O at 1 mg/ml and were probe-sonicated for 1 min (Model W-p200, setting 4; Ultrasonics, Plainview, NY) immediately before use.

CAPs Treatment

To isolate soluble and insoluble fractions of CAPs, the particle suspension was centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C to pellet particulates. The supernatant (soluble fraction) was recovered and the pellet was resuspended in equal volume of H2O (and is referred to as the insoluble fraction). Both fractions were assayed together with the original CAPs particle suspension (referred to as whole CAPs). In some experiments the soluble CAPs sample was treated with the chelating resin, Chelex 100 (Sigma) (100 mg chelex/0.1 mg CAPs). A control sample comprising an identical volume of sterile deionized distilled water was also treated with resin. The samples were mixed well and incubated on a rotor for 2–3 h at room temperature, centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 5 min to pellet the chelex beads, and the chelated supernatant was recovered (designated as sCAPs+chelex or H2O+chelex).

Binding, Phagocytosis, and Killing Assay

A standard bacterial uptake and killing assay was used to evaluate the effect of pretreatment of macrophages (500 k cells/0.5 ml in BSS+) with CAPs (100 μg/ml). After incubation with CAPs for 1 h at 37°C, macrophages were interacted with S. pneumoniae for 1 h at 37°C (bacteria to macrophage ratio ∼ 10:1), unbound bacteria were washed away by PBS for three times. To measure total uptake bacteria at this time point, the cells were lysed by cold water (pH 10.5) and vortexed vigorously for 1 min, then sat for 20–30 min at room temperature. The lysates were diluted in PBS and plated onto sheep-blood agar plate (BD Diagnostic Systems, Sparks, MD) and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. Colony-forming units were counted after 16 h incubation. The total bound bacteria were calculated by subtracting the cfu total inside after gentamycin treatment from the total cfu (bound and inside) (see Figure 1A). To evaluate phagocytosis, 100 μg/ml of gentamycin (Sigma) was added to separate aliquots to kill extracellular bacteria for 15 min at 37°C (28, 29). To study killing of ingested bacteria, the cells were incubated for another hour at 37°C. Samples at each stage were lysed and bacterial numbers measured by cfu assay. The number of bacteria killed by the macrophages was determined by subtracting the number of viable cfu counted from phagocytosis cfu. These three stages are summarized in Figure 1A.

Figure 1.

Protocols used to analyze macrophage interaction with S. pneumoniae. (A) Main protocol used to measure in vitro binding, internalization, and killing of S. pneumoniae: AMs were pre-incubated with 100 μg/ml of CAPs for 1 h at 37°C before addition of S. pneumoniae, followed by analysis of binding and killing as shown. (B) Protocol designed to focus on the internalization phase of bacteria uptake. Macrophages were allowed to bind bacteria for 1 h at 4°C (binding only). After washing away unbound bacteria with ice cold BSS+, CAPs (100 μg/ml) were added and incubated for 1 h at 37°C, followed by analysis of internalization and killing as shown.

To focus on the internalization phase of macrophage phagocytosis of S. pneumoniae, we used a modified protocol as summarized in Figure 1B. In these experiments, we incubated macrophages with bacteria at 4°C to first allow binding without internalization. After washing away unbound bacteria three times with ice cold BSS+, CAPs samples were then added and incubated for 1 h at 37°C, and samples were subsequently evaluated for internalization of bacteria by cfu counting of lysed samples as above.

Statistical Analysis

Experiments were conducted, at minimum, in triplicate and all data are presented as mean ± SD. All tests were performed using software GraphPad Prism 3.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Student's t tests were run to determine P values when comparing two groups. For three or more groups, differences among groups were evaluated using ANOVA with a post hoc Bonferroni's multiple comparison test. For all analyses, a value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Effects of CAPs on Macrophage Interactions with S. pneumoniae

To investigate whether CAPs impair macrophage interactions with Streptococcus pneumoniae, we measured the three components of phagocytosis (binding, internalization and killing) in primary alveolar macrophages (AMs) (with or without priming by IFN-γ) and the murine macrophage cell line J774A.1, using the protocol summarized in Figure 1A. Results shown are from one CAPs sample; similar results were seen with two other CAPs samples collected on different days (data not shown).

Binding.

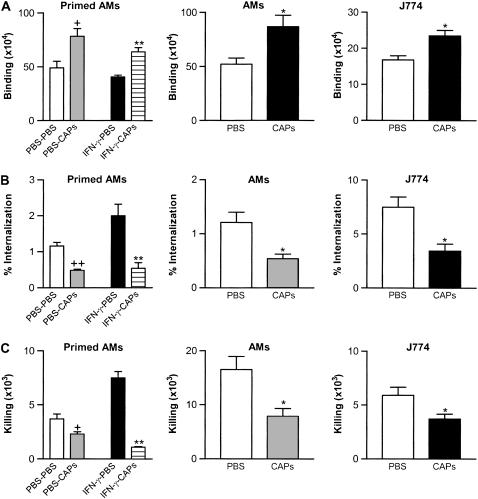

Compared with the control group treated with buffer only (PBS), CAPs caused increased binding of S. pneumoniae bacteria by all three types of macrophages studied: IFN-γ–primed AMs, normal AMs, and J774A.1 cells showed increased binding of 57.9 ± 5.6%, 66.7 ± 10.6%, and 58.9 ± 4.0%, respectively (n = 4) (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

CAPs effects on interaction of macrophages (IFN-γ–primed AMs, primary AMs, and the J774A.1 macrophage cell line) with S. pneumoniae. (A) CAPs cause increased binding of S. pneumoniae. The y-axis represents the total bound cfu, calculated by subtracting the cfu measured after incubation with gentamycin from the total cfu (bound and inside). (B) CAPs cause decreased internalization. The y-axis label “% Internalization” represents the percentage of bound bacteria that were internalized. (C) CAPs cause decreased total killing. CAPs used at 100 μg/ml; all data are presented as mean ± SD; n = 4. +P < 0.05 and ++P < 0.01 compared with control (PBS-PBS); *P < 0.05 compared with control (PBS); **P < 0.01 compared with control (IFN-γ–PBS).

Internalization.

In contrast to the finding of increased binding, analysis showed decreased internalization of bound bacteria by all three types of macrophages, as shown in Figure 2B. Internalization of S. pneumoniae was reduced in IFN-γ–primed AMs, normal AMs, and J774A.1 cells by 73.9 ± 9.3%, 55.4 ± 8.5%, and 54.7 ± 5.1% compared with no CAPs control groups, respectively (n = 4).

Killing.

The rate of killing of internalized bacteria was similar in the presence or absence of CAPs. For primary AMs, the rate of killing was 65.7 ± 6.9% with CAPs compared with no CAPs group 69.3 ± 8.1%; for J774 macrophage cell line, the rate of killing was 61.0 ± 1.9% with CAPs versus 65.3 ± 5.2% without CAPs, but CAPs caused a decrease in the absolute number of bacteria killed by all three types of macrophages studied (Figure 2C), due to the decrease in internalization.

Effects of Other Particles

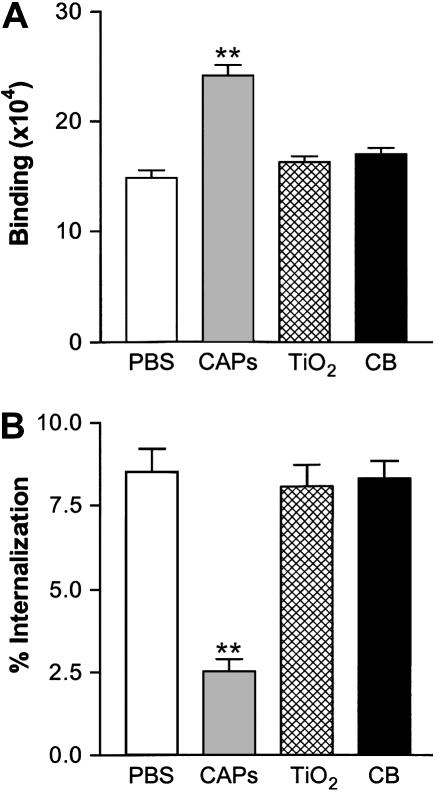

To investigate the specificity of CAPs effects, we compared effects on macrophage interaction with bacteria by CAPs to those of a panel of other environmental particles or surrogates. In contrast to CAPs, the inert particles titanium dioxide (TiO2) and carbon black (CB) had no effect on J774 binding or internalization of S. pneumoniae (Figures 3A and 3B). However, effects similar to those observed with CAPs were found upon testing another urban air particle sample (UAP), the SRM 1649 sample of Washington, D.C. air particles (data not shown).

Figure 3.

CAPs, but not inert particles, TiO2 or CB, increase J774A.1 binding (A) and decrease internalization (B) of S. pneumoniae. Final concentration of each particle is 50 μg/ml. All data represent mean ± SD; n = 3. **P < 0.01 versus control PBS.

Soluble Components of CAPs Inhibit Macrophage Internalization of S. pneumoniae

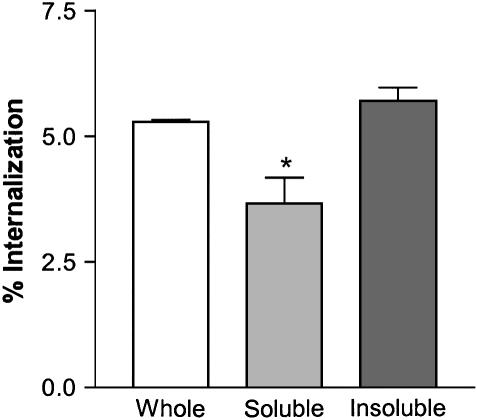

To focus on the internalization phase of macrophage ingestion of S. pneumoniae, we used the modified protocol summarized in Figure 1B. Macrophages were pre-loaded with bacteria by binding at 4°C for 1 h, CAPs components were then added, and effects on internalization of bacteria measured after 1 h at 37°C. We first tested the effects of the soluble and insoluble fractions of CAPs suspensions and compared them with the whole CAPs sample. The results showed that the soluble fraction of CAPs (sCAPs) is responsible for decreased internalization (while the isolated insoluble fraction had minimal effect in the same assay) (Figure 4). Hence, we next further analyzed the soluble CAPs components.

Figure 4.

Soluble components of CAPs mediate decreased phagocytosis of S. pneumoniae by macrophages. Whole CAPs: 100 μg/ml. All values are mean ± SD for three separate experiments, each performed in duplicate. *P < 0.05 compared with control whole CAPs.

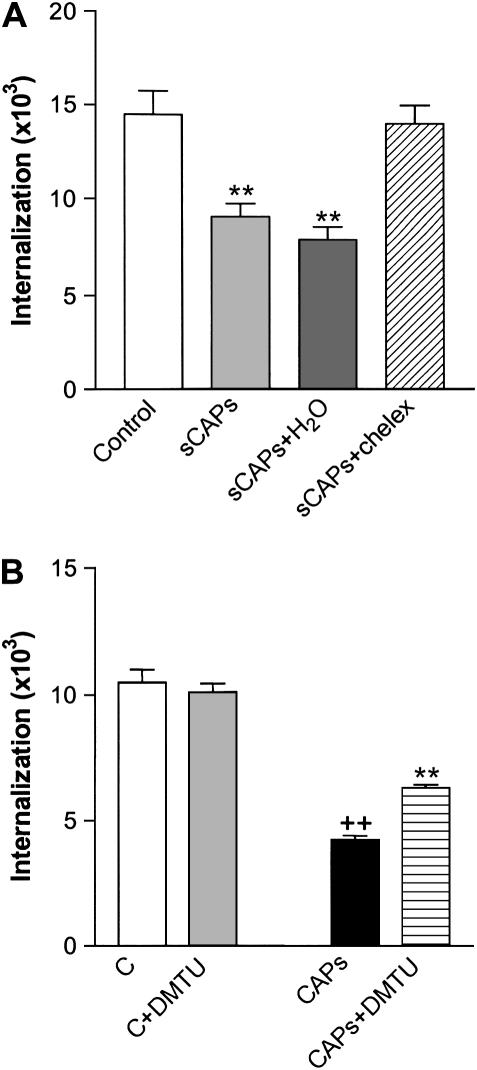

Soluble metals, especially iron, are released by air particle samples in aqueous solution and are linked to cytotoxic and biological effects (30–32). To determine the contribution of iron and other metals in the effect of soluble CAPs on bacterial ingestion, we used both chelation to remove metals from CAPs samples and addition of soluble metals. Using the analysis of internalization protocol (Figure 1B), we found that chelation treatment of soluble CAPs substantially reversed the ability of these samples to mediate inhibition of internalization of streptococcus (Figure 5A).

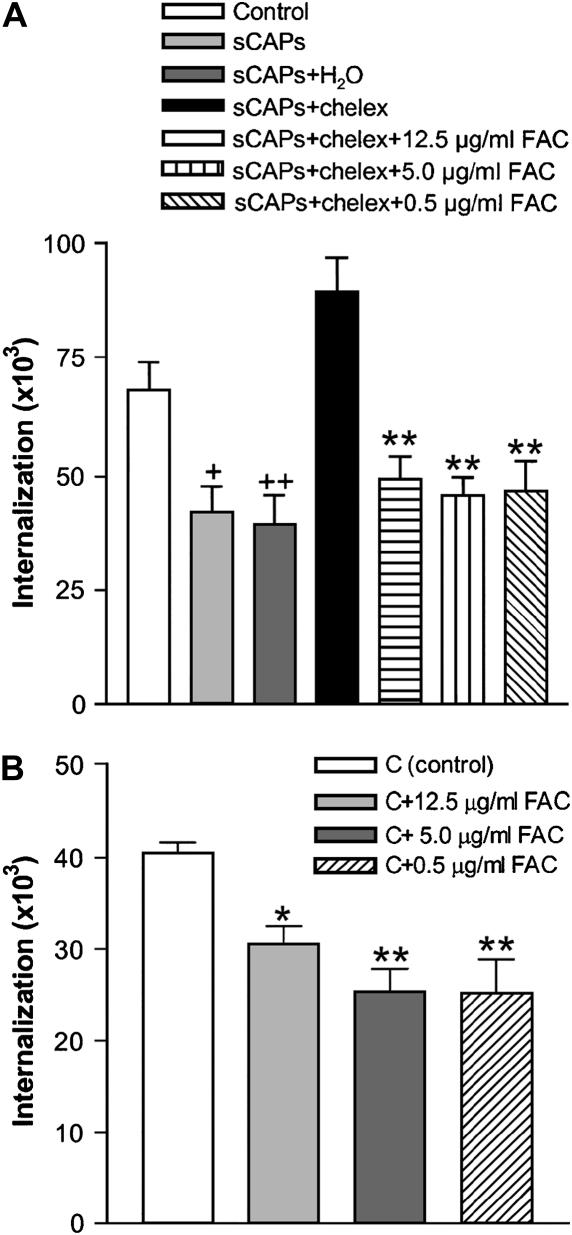

Figure 5.

(A) Chelation of iron in soluble CAPs (sCAPs) using chelex beads substantially reversed CAPs-mediated inhibition of J774 phagocytosis of S. pneumoniae. sCAPs+ H2O, soluble CAPs with chelex-treated sterile deionized distilled H2O; sCAPs+chelex, soluble CAPs were treated with chelex beads. All values are mean ± SD for six separate experiments, each performed in duplicate. **P < 0.01 versus control group. (B) The antioxidant DMTU partially reversed CAPs mediated J774 inhibition of phagocytosis of S. pneumoniae. DMTU: 1 mM/ml. All values represent mean ± SD (n = 3). ++P < 0.01 versus control (C); **P < 0.01 versus CAPs group.

Oxidant stress induced by soluble metals in CAPs samples may mediate the damage to internalization machinery of the macrophage. This postulate was supported by the observation that the antioxidant dimethyl-thiourea (DMTU, 1 mM) partially reversed CAPs-mediated inhibition of internalization of streptococcus (Figure 5B); no increased effect was observed at 10 or 20 mM DMTU, and no effect at all was observed using N-acetylcysteine (NAC) 10 mM (data not shown).

To further test the potential role of iron in the inhibition of phagocytosis by soluble fraction of CAPs, we added back iron in the form of ferric ammonium citrate (FAC) to a soluble CAPs sample which had been treated with chelation, and found the addition of soluble iron restored the impairment of internalization (Figure 6A). Moreover, this observation was also supported by the ability of FAC by itself to cause impaired internalization of bacteria when added to macrophage cultures (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

(A) FAC restores inhibition of internalization to soluble CAPs treated with chelex (sCAPs+chelex). Different concentrations of FAC were added to chelex-treated soluble CAPs (sCAPs+chelex+FAC), and effects on internalization of bacteria measured. Bars represent means ± SD of five separate experiments (n = 5). +P < 0.05, ++P < 0.01 versus control; **P < 0.01 compared with group sCAPs+chelex. (B) Addition of FAC to J774 macrophages inhibits internalization of S. pneumoniae. Bars represent means ± SD of three independent experiments (n = 3). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 compared with control (C).

DISCUSSION

The study found that air pollution particles cause a functional impairment of the antibacterial capacities of murine macrophages. A main finding is that concentrated air particles (CAPs) cause a specific inhibition of the internalization phase of macrophage bacterial uptake. Although the killing rate was not affected per se, the impaired internalization resulted in an overall decrease in killing with more viable bacteria surviving. Similar results were also observed with a standard reference material sample of urban air particles collected in another city (data not shown) but not with other inert particles, TiO2 and carbon black.

One intriguing aspect of the epidemiological data is that air particle health effects are primarily seen in those people with preexisting inflammatory lung disease, while little or no effect is seen in normal individuals with healthy lungs (2, 3, 5). Our hypothesis is that in the inflammatory milieu of diseased lungs, AMs may be primed for enhanced responses to inhaled air particles. In vitro, lipopolysaccharide priming substantially enhances particle-mediated TNF release by AMs from both rat and human sources (26). Moreover, we have observed that CAPs cause decreased bacterial clearance and increased pneumonic inflammation in mice in vivo, and that IFN-γ priming of mice before CAPs administration substantially enhances this effect (unpublished data). In contrast, the in vitro data from the studies reported here show similar results in primary AMs with and without priming. The basis for the greater dysfunction after priming in vivo remains to be determined. To further analyze the basis of the CAPs-mediated defect in bacterial internalization shared by control or primed AMs, we used the J744A.1 macrophage cell line for more detailed analysis of CAPs components and mechanisms.

Our interpretation that the internalization phase is the major defect in CAPs-exposed macrophage phagocytosis is based on similar findings using a general uptake assay (Figures 1–3A) and an internalization-specific protocol (Figures 3B–6). An alternative possibility is that CAPs increase binding but the internalization mechanism is saturated. We consider this unlikely, since the average number of bacteria per cell, even in the CAPs-treated macrophages that show increased binding (e.g., Figure 2), is ∼ 1–2, and only a small number are internalized (as previously reported for encapsulated S. pneumoniae type III [33]). It is also more likely that decreased internalization would lead to decreased bacterial clearance as observed epidemiologically and experimentally (7, 18, 34). Nevertheless, pilot studies in our laboratory show that the increased binding of pneumococci can be partially blocked by antagonists of the platelet-activating factor receptor (35) or scavenger receptors (36) (data not shown). The possibility that CAPs cause increased surface expression or avidity of these receptors merits future exploration.

Oxygen radicals and their metabolites (ROS) have been reported to play a major role in pulmonary toxicity caused by the inhalation of different particles (37–39). In our study, the antioxidant DMTU caused partial reversal of inhibition of phagocytosis, suggesting that CAPs caused diminished macrophage internalization due to CAPs-mediated oxidant stress in the cells. CAPs may also alter other cytokine production in macrophages, which might in turn affect macrophage ingestion of the intracellular pathogens.

The pulmonary toxicity of complex metal-containing particulates can be associated with the soluble forms of transition metals and the dose (32, 40–44). Particles containing easily solubilized metals cause a more rapid onset and severity of acute lung injury (42). Moreover, Antonini and colleagues (45) demonstrated that the solubility of welding fumes influenced the viability and the production of ROS in lung macrophages in vitro. Wilson and coworkers (46) also showed that untrafine carbon particles induced inflammation in the rat lung that was potentiated by the addition of iron chloride. In our study, we separated whole CAPs sample into soluble and insoluble fractions and compared their role in macrophage binding and phagocytosis of S. pneumoniae. Our results indicated that soluble components of CAPs appear to contribute significantly to the increase of binding and decrease of internalization.

We hypothesized that iron in the soluble components may play a key role in the phagocytosis. To address this issue, the soluble fraction of CAPs was treated with chelex beads (chelex-100) to remove soluble metals. These beads have an especially high affinity for iron (32, 47, 48). In contrast to the soluble CAPs, the chelex-treated soluble fraction did not inhibit internalization. Furthermore, adding FAC back to the chelex-treated fraction restored inhibition of internalization. For the control macrophages (without CAPs treatment), the addition of FAC also showed inhibition of internalization. These results indicate that soluble metal, especially iron, in the CAPs plays an important role in the inhibition of macrophage phagocytosis.

These data identify the macrophage internalization machinery as a key target for particle toxic effects. Future studies using a proteomics approach (49, 50) to identify oxidatively modified proteins in CAPs-exposed macrophages may provide further insights.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Zhiping Yang for her help with the bacteria killing assay.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant ES011008 011903 00002 and Ruth K. Kirschstein National Research Service Awards (NRSA) grant T32 HL007118-29.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0293OC on November 1, 2006

Conflict of Interest Statement: Neither author has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Dockery DW, Pope CA III, Xu X, Spengler JD, Ware JH, Fay ME, Ferris BG Jr, Speizer FE. An association between air pollution and mortality in six US cities. N Engl J Med 1993;329:1753–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pope CA III, Bates DV, Raizenne ME. Health effects of particulate air pollution: time for reassessment? Environ Health Perspect 1995;103:472–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartz J. Air pollution and daily mortality: a review and meta analysis. Environ Res 1994;64:36–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dominici F, Peng RD, Bell ML, Pham L, McDermott A, Zeger SL, Samet JM. Fine particulate air pollution and hospital admission for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. JAMA 2006;295:1127–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz J. What are people dying of on high air pollution days? Environ Res 1994;64:26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwartz J. Air pollution and hospital admissions for the elderly in Detroit, Michigan. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994;150:648–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwartz J. Air pollution and hospital admissions for respiratory disease. Epidemiology 1996;7:20–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu O, Sheppard L, Lumley T, Koenig JQ, Shapiro GG. Effects of ambient air pollution on symptoms of asthma in Seattle-area children enrolled in the CAMP study. Environ Health Perspect 2000;108:1209–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harrison RM, Yin J. Particulate matter in the atmosphere: which particle properties are important for its effects on health? Sci Total Environ 2000;249:85–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sibille Y, Reynolds HY. Macrophages and polymorphonuclear neutrophils in lung defense and injury. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990;141:471–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brain JD. Toxicological aspects of alterations of pulmonary macrophage function. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 1986;26:547–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lehnert BE. Pulmonary and thoracic macrophage subpopulations and clearance of particles from the lung. Environ Health Perspect 1992;97:17–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lohmann-Matthes ML, Steinmuller C, Franke-Ullmann G. Pulmonary macrophages. Eur Respir J 1994;7:1678–1689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldsmith CA, Imrich A, Danaee H, Ning YY, Kobzik L. Analysis of air pollution particulate-mediated oxidant stress in alveolar macrophages. J Toxicol Environ Health A 1998;54:529–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Becker S, Soukup JM, Gilmour MI, Devlin RB. Stimulation of human and rat alveolar macrophages by urban air particulates: effects on oxidant radical generation and cytokine production. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1996;141:637–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ning Y, Imrich A, Goldsmith CA, Qin G, Kobzik L. Alveolar macrophage cytokine production in response to air particles in vitro: role of endotoxin. J Toxicol Environ Health A 2000;59:165–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hatch GE, Boykin E, Graham JA, Lewtas J, Pott F, Loud K, Mumford JL. Inhalable particles and pulmonary host defense: in vivo and in vitro effects of ambient air and combustion particles. Environ Res 1985;36:67–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang HM, Antonini JM, Barger MW, Butterworth L, Roberts BR, Ma JK, Castranova V, Ma JY. Diesel exhaust particles suppress macrophage function and slow the pulmonary clearance of Listeria monocytogenes in rats. Environ Health Perspect 2001;109:515–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hahon N. Inhibition of viral interferon induction in mammalian cell cultures by azo dyes and derivatives activated with rat liver S9 fraction. Environ Res 1985;37:228–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Antonini JM, Roberts JR, Jernigan MR, Yang HM, Ma JY, Clarke RW. Residual oil fly ash increases the susceptibility to infection and severely damages the lungs after pulmonary challenge with a bacterial pathogen. Toxicol Sci 2002;70:110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schuchat A, Hilger T, Zell E, Farley MM, Reingold A, Harrison L, Lefkowitz L, Danila R, Stefonek K, Barrett N, et al. Active bacterial core surveillance of the emerging infections program network. Emerg Infect Dis 2001;7:92–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Briles DE, Novak L, Hotomi M, van Ginkel FW, King J. Nasal colonization with Streptococcus pneumoniae includes subpopulations of surface and invasive pneumococci. Infect Immun 2005;73:6945–6951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCullers JA, Tuomanen EI. Molecular pathogenesis of pneumococcal pneumonia. Front Biosci 2001;6:D877–D889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Welsh DA, Mason CM. Host defense in respiratory infections. Med Clin North Am 2001;85:1329–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knapp S, Leemans JC, Florquin S, Branger J, Maris NA, Pater J, van Rooijen N, van der Poll T. Alveolar macrophages have a protective antiinflammatory role during murine pneumococcal pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167:171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Imrich A, Ning YY, Koziel H, Coull B, Kobzik L. Lipopolysaccharide priming amplifies lung macrophage tumor necrosis factor production in response to air particles. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1999;159:117–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Imrich A, Ning Y, Kobzik L. Insoluble components of concentrated air particles mediate alveolar macrophage responses in vitro. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2000;167:140–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahmed HJ, Johansson C, Svensson LA, Ahlman K, Verdrengh M, Lagergard T. In vitro and in vivo interactions of Haemophilus ducreyi with host phagocytes. Infect Immun 2002;70:899–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tabrizi SN, Robins-Browne RM. Elimination of extracellular bacteria by antibiotics in quantitative assays of bacterial ingestion and killing by phagocytes. J Immunol Methods 1993;158:201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zelikoff JT, Schermerhorn KR, Fang K, Cohen MD, Schlesinger RB. A role for associated transition metals in the immunotoxicity of inhaled ambient particulate matter. Environ Health Perspect 2002;110:871–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts JR, Taylor MD, Castranova V, Clarke RW, Antonini JM. Soluble metals associated with residual oil fly ash increase morbidity and lung injury after bacterial infection in rats. J Toxicol Environ Health A 2004;67:251–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McNeilly JD, Heal MR, Beverland IJ, Howe A, Gibson MD, Hibbs LR, MacNee W, Donaldson K. Soluble transition metals cause the pro-inflammatory effects of welding fumes in vitro. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2004;196:95–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jonsson S, Musher DM, Chapman A, Goree A, Lawrence EC. Phagocytosis and killing of common bacterial pathogens of the lung by human alveolar macrophages. J Infect Dis 1985;152:4–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lundborg M, Dahlen SE, Johard U, Gerde P, Jarstrand C, Camner P, Lastbom L. Aggregates of ultrafine particles impair phagocytosis of microorganisms by human alveolar macrophages. Environ Res 2006;100:197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cundell DR, Gerard NP, Gerard C, Idanpaan-Heikkila I, Tuomanen EI. Streptococcus pneumoniae anchor to activated human cells by the receptor for platelet-activating factor. Nature 1995;377:435–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Platt N, Gordon S. Is the class A macrophage scavenger receptor (SR-A) multifunctional? The mouse's tale. J Clin Invest 2001;108:649–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gonzalez-Flecha B. Oxidant mechanisms in response to ambient air particles. Mol Aspects Med 2004;25:169–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hatzis C, Godleski JJ, Gonzalez-Flecha B, Wolfson JM, Koutrakis P. Ambient particulate matter exhibits direct inhibitory effects on oxidative stress enzymes. Environ Sci Technol 2006;40:2805–2811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vallyathan V, Shi X. The role of oxygen free radicals in occupational and environmental lung diseases. Environ Health Perspect 1997;105:165–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adamson IY, Prieditis H, Hedgecock C, Vincent R. Zinc is the toxic factor in the lung response to an atmospheric particulate sample. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2000;166:111–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carter JD, Ghio AJ, Samet JM, Devlin RB. Cytokine production by human airway epithelial cells after exposure to an air pollution particle is metal-dependent. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1997;146:180–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dreher KL, Jaskot RH, Lehmann JR, Richards JH, McGee JK, Ghio AJ, Costa DL. Soluble transition metals mediate residual oil fly ash induced acute lung injury. J Toxicol Environ Health 1997;50:285–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kennedy T, Ghio AJ, Reed W, Samet J, Zagorski J, Quay J, Carter J, Dailey L, Hoidal JR, Devlin RB. Copper-dependent inflammation and nuclear factor-kappaB activation by particulate air pollution. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1998;19:366–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hetland RB, Myhre O, Lag M, Hongve D, Schwarze PE, Refsnes M. Importance of soluble metals and reactive oxygen species for cytokine release induced by mineral particles. Toxicology 2001;165:133–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Antonini JM, Lawryk NJ, Murthy GG, Brain JD. Effect of welding fume solubility on lung macrophage viability and function in vitro. J Toxicol Environ Health A 1999;58:343–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilson MR, Lightbody JH, Donaldson K, Sales J, Stone V. Interactions between ultrafine particles and transition metals in vivo and in vitro. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2002;184:172–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gao Y, Oshita K, Lee KH, Oshima M, Motomizu S. Development of column-pretreatment chelating resins for matrix elimination/multi-element determination by inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry. Analyst 2002;127:1713–1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hutchison GR, Brown DM, Hibbs LR, Heal MR, Donaldson K, Maynard RL, Monaghan M, Nicholl A, Stone V. The effect of refurbishing a UK steel plant on PM10 metal composition and ability to induce inflammation. Respir Res 2005;6:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang M, Xiao GG, Li N, Xie Y, Loo JA, Nel AE. Use of a fluorescent phosphoprotein dye to characterize oxidative stress-induced signaling pathway components in macrophage and epithelial cultures exposed to diesel exhaust particle chemicals. Electrophoresis 2005;26:2092–2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiao GG, Wang M, Li N, Loo JA, Nel AE. Use of proteomics to demonstrate a hierarchical oxidative stress response to diesel exhaust particle chemicals in a macrophage cell line. J Biol Chem 2003;278:50781–50790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]