Abstract

The AppA protein of Rhodobacter sphaeroides has the unique ability to sense and transmit redox and light signals. In response to decreasing oxygen tension, AppA antagonizes the transcriptional regulator PpsR, which represses the expression of photosynthesis genes, including the puc operon. This mechanism, which is based on direct protein-protein interaction, is prevented by blue-light absorption of the BLUF domain located in the N-terminal part of AppA. In order to test whether AppA and PpsR are sufficient to transmit redox and light signals, we expressed these proteins in three different bacterial species and monitored oxygen- and blue-light-dependent puc expression either directly or by using a luciferase-based reporter construct. The AppA/PpsR system could mediate redox-dependent gene expression in the alphaproteobacteria Rhodobacter capsulatus and Paracoccus denitrificans but not in the gammaproteobacterium Escherichia coli. Analysis of a prrA mutant strain of R. sphaeroides strongly suggests that light-dependent gene expression requires a balanced interplay of the AppA/PpsR system with the PrrA response regulator. Therefore, the AppA/PpsR system was unable to establish light signaling in other bacteria. Based on our data, we present a model for the interdependence of AppA/PpsR signaling and the PrrA transcriptional activator.

Rhodobacter sphaeroides is a facultative photosynthetic bacterium that forms large amounts of photosynthetic complexes only at low oxygen concentrations (or under anaerobic growth conditions), when photosynthesis genes are transcribed at maximal level. This O2-regulated photosystem includes the photosynthetic reaction center and light-harvesting complexes 1 and 2 (LH1 and -2). The pigment binding proteins encoded by the puc (LH2) and puf (reaction center and LH1) operons assemble with bacteriochlorophyll (BChl) and carotenoids (Crt) to capture light energy. At intermediate oxygen concentrations (∼100 μM dissolved oxygen), the transcription rate of photosynthesis genes, although not maximal, is repressed by blue light (4, 5, 46). This may provide a protection against photooxidative stress caused by the generation of singlet oxygen in the simultaneous presence of BChl, light, and oxygen.

The AppA and PpsR proteins of Rhodobacter sphaeroides are involved in redox and light regulation of photosynthesis genes (4, 16-18, 36). In response to a decrease in oxygen tension, AppA was found to interact with and to antagonize the transcriptional repressor PpsR that otherwise binds to a consensus sequence (TGTN12ACA) located in tandem upstream of its target genes (18, 36, 40). No PpsR binding sites were found in proximity to the puf promoter, and it is still unknown how PpsR affects puf expression. Blue-light absorption by AppA results in dissociation of the AppA-PpsR complex (36), and free PpsR represses the expression of its target genes even at an intermediate oxygen concentration.

The blue-light-absorbing N-terminal part of AppA consists of a new type of spectrally active flavin adenine dinucleotide binding domain (19), designated BLUF (for blue light sensing using flavin adenine dinucleotide) (20). The BLUF domain is also found in other bacteria (20) and in the PAC proteins of Euglena gracilis (27). It functions in modules, since it can signal to the C-terminal AppA output domain without covalent linkage (23). The C-terminal part of AppA is sufficient for normal redox regulation of photosynthesis genes (23). Several investigations have addressed the photochemistry of the BLUF domain, and different mechanisms of signal recognition and transmission to the C-terminal part of AppA have been proposed (1, 15, 33, 35, 36, 38-39). Nevertheless, the exact mechanisms of redox and light transmission by AppA have remained unknown.

Redox regulation in R. sphaeroides occurs not only via an AppA/PpsR-dependent repression of photosynthesis genes, but also via the PrrB/PrrA two-component system, a major redox regulator that activates photosynthesis genes in response to a decrease in the oxygen tension. At low oxygen tension, the sensor kinase PrrB undergoes autophosphorylation and transfers the phosphoryl group to the corresponding response regulator, PrrA (12, 42). The phosphorylated DNA binding protein PrrA activates the transcription of several photosynthesis genes, including those of the puc operon (9, 14).

Light qualities that are absorbed by the photosynthetic apparatus of Rhodobacter under anaerobic conditions lead to increased expression of photosynthesis genes (4, 24). The signal arises from the subsequent photosynthetic electron transport and is transmitted via components of the respiratory chain and the PrrB/PrrA two-component system (24). The stimulating signal transmitted by PrrB/PrrA overwrites the blue-light inhibition mediated by AppA/PpsR if little or no oxygen is present. Thus, the oxygen tension determines whether light has a stimulating or repressing effect on the expression of photosynthesis genes.

To test whether the R. sphaeroides AppA and PpsR proteins constitute a complete signaling chain for light and redox signals, we expressed the corresponding genes in the three bacterial species Rhodobacter capsulatus, Paracoccus denitrificans, and Escherichia coli and monitored puc expression either directly or by using luciferase-based reporter constructs.

R. capsulatus is a close relative of R. sphaeroides. The two alphaproteobacteria exhibit similar genetic organizations and oxygen-dependent regulation of their photosynthesis genes, including the puc operon (11, 21, 22, 52). However R. capsulatus, which harbors the PpsR homologue CrtJ (53% identity) but lacks an AppA homologue, shows no blue-light-dependent gene repression (4). CrtJ was shown to repress gene expression, depending on redox conditions, undergoing an intrinsic dithiol-disulfide switch that alters its DNA binding affinity (37). We also monitored AppA/PpsR-dependent signaling with puc reporter plasmids in the nonphototrophs P. denitrificans and E. coli, which both lack PpsR and AppA homologues. P. denitrificans, like Rhodobacter, is a member of the alphaproteobacteria. Its transcription machinery is similar to that of Rhodobacter, allowing the use of a native puc promoter construct. E. coli belongs to the gamma subgroup of proteobacteria, and several Rhodobacter-type promoters are not transcribed in the bacterium, suggesting that the transcription machineries of the two species exhibit marked differences. Therefore, after expressing PpsR and AppA in E. coli, blue-light-dependent transcription of the luciferase genes was analyzed under the control of different E. coli-type promoters. Our results suggest that a balanced interplay between the AppA/PpsR system and the response regulator PrrA is required for blue-light-dependent regulation of photosynthesis genes at intermediate oxygen concentrations in R. sphaeroides. Therefore, expression of AppA and PpsR in other bacteria does not establish blue-light signaling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Strains and plasmids are listed in Table 1. Rhodobacter strains were cultivated at 32°C in a malate minimal salt medium. E. coli and P. denitrificans strains were cultured in Luria-Bertani broth at 37°C. Oxygen tension was adjusted by varying the rotation speed of the shaker and was monitored with a Pt-Ag electrode (micro-oxygen sensor 501; Umwelt-, Membran- und Sensortechnik, Meiningen, Germany). To analyze AppA-dependent light-signaling characteristics, strains were irradiated with blue light (λmax, 400 nm; fluence rate, 20 μmol m−2 s−1) in the presence of 104 ± 24 μM dissolved oxygen, as described previously (4). To analyze the redox-dependent functions, the concentration of dissolved oxygen was decreased from 200 μM to ≤3 μM in dark-grown cultures.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| R. sphaeroides 2.4.1 | Wild- type strain | 48 |

| R. sphaeroides PrrA2 | 2.4.1 derivative; chromosomal deletion of prrA and insertion of ΩSpr Smr resistance cassette | 14 |

| R. sphaeroides PrrB1 | 2.4.1 derivative; chromosomal deletion of prrB and insertion of ΩSpr Smr resistance cassette | 13 |

| R. capsulatus SB1003 | Wild-type strain | 51 |

| R. capsulatus DB469 DB | crtJ gene of strain SB1003 inactivated by insertion of Kmr cassette | 2 |

| P. denitrificans | Wild-type strain | DSMZ 413 |

| E. coli MC1061 | Host for primary transformation | 6 |

| E. coli S17-1 | Donor strain for diparental conjugation | 47 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pRK415 | Tcr | 28 |

| pRKcrtJ | crtJ gene from R. sphaeroides cloned into XbaI and KpnI sites or pRK415 | This work |

| PRKppsR | ppsR gene from R. sphaeroides cloned into PstI and KpnI sites or pRK415 | This work |

| pRKppsRappA | appA gene inserted into the HindIII site of pRKppsR | This work |

| pBBR2puclux | pucBA genes from R. sphaeroides 2.4.1 transcriptionally fused to the luxAB genes from Vibrio harveyi | 23 |

| pQE31 | Vector for overexpression with N-terminal His tag | QIAGEN |

| pQET5lux | pQE31 promoter replaced by the T5 promoter with two PpsR binding sites upstream | This work |

| pQEblalux | pQE31 promoter replaced by the bla promoter with two PpsR binding sites upstream | This work |

| pQElaclux | pQE31 promoter replaced by the lac promoter with two PpsR binding sites upstream | This work |

| p484-Nco5 | pRK415 derivative containing the appA gene under the control of a lac promoter | 16 |

For determination of the bacteriochlorophyll content, cells of Rhodobacter sphaeroides were first grown aerobically (a 100-ml culture shaken at 130 rpm in a 1-liter flask) and then shifted to low-oxygen conditions (75 ml of the aerobically grown culture in a 100-ml flask at 130 rpm).

Rhodobacter conjugation was performed as described elsewhere (31). When required, antibiotics were used at the following final concentrations: gentamicin, 10 μg ml−1; kanamycin, 25 μg ml−1; spectinomycin, 10 μg ml−1; streptomycin, 100 μg ml−1 (E. coli) or 25 μg ml−1 (R. sphaeroides); tetracycline, 20 μg ml−1 (E. coli) or 2 μg ml−1 (R. sphaeroides); ampicillin, 200 μg ml−1 (E. coli). In the presence of light, no tetracycline was used.

Genetic techniques.

DNA cloning was performed according to standard protocols (45). Oligonucleotides carrying suitable recognition sites for cloning were synthesized by Carl Roth GmbH (Karlsruhe, Germany). DNA sequencing was performed with the ABI-Prism 310 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

Plasmid construction.

The luxAB genes were amplified from plasmid pILA (34) using primers luxAB F and luxAB R (primer sequences are listed in Table 2), and the fragment was cut by BamHI and inserted into the corresponding restriction sites of pQE31. puc upstream sequences were amplified from chromosomal DNA of R. sphaeroides by using primer pucup100, which anneals about 100 nucleotides upstream of the transcriptional start of the puc operon, and one of the following primers that anneal close to the transcriptional start of the puc operon and carry tags with sequences for the different promoters: for the lac promoter, pucdownlac; for the T5 promoter, pucdownT5; for the bla promoter, pucdownbla. The resulting DNA fragments were cut by XhoI and EcoRI and inserted into the corresponding restriction sites of the pQE31 derivative harboring the luxAB genes.

TABLE 2.

PCR primers used in this study

| PCR primer | Sequence (5′→3′) |

|---|---|

| luxAB F | GGCGCAAGATGTTTGTCGG |

| luxAB R | TGTCATAAAGCGTCGCATGG |

| pucup100 | GGGGGGAATTCAACATACGAGCCGGAAGCATAAAGGGTGTCACATTGCGCTGAC |

| pucdownlac | GGGGGGAATTCTGAATCTATTATAATTGTTATCCGCTCACAGGGTGTCACATTGCGCTGAC |

| pucdownT5 | GGGGGGAATTCTGAATCTATTATAATTGTTATCCGCTCACAGGGTGTCACATTGCGCTGAC |

| pucdownbla | GGGGGGAATTCGGTAGTTTATCACAGTTAAATTGCTAACGCAGTCAGGCAGGGTGTCACATTGCGCTGAC |

| appA F | AGGAGAAGCTTGGAGAGCAGCA |

| appA R | CCGCAAGCTTCACCTCTGCCCG |

| ppsR F | CGGCGCTGCAGGCCTGCG |

| ppsR R | GCGGACGGTACCACACTTTCC |

| crtJ F | GCAGATCTAGAGACGAACGAT |

| crtJ R | GAAACGGGTACCGGAAAAAGG |

| rpoZ F | ATCGCGGAAGAGACCCAGAG |

| rpoZ R | GAGCAGCGCCATCTGATCCT |

| puf F | ACATCTGGCGTCCGTGGTTC |

| puf R | ATCACCGCGAGGAGGAACAG |

| puc F | GGCAAAATCTGGCTCGTGGT |

| puc R | GGTTGGTGGTCGTCAGCACAG |

Construction of pBBR2puclux was performed as described before (23).

The appA and ppsR genes were amplified from chromosomal DNA of R. sphaeroides 2.4.1 in a PCR by using the primer pairs appA F and appA R or ppsR F and ppsR R, respectively. The resulting ppsR fragment was cut with PstI and KpnI and cloned into the respective sites of plasmid pRK415 to yield plasmid pRKppsR. The appA PCR product was cut by HindIII and inserted into the HindIII site of pRKppsR to yield pRKppsRappA. The crtJ gene of R. capsulatus SB1003 was amplified using primers crtJ F and crtJ R and inserted into the XbaI and KpnI sites of plasmid pRK415 to yield pRKcrtJ.

Gene expression analyses.

Expression of puc, puf, and rRNA genes was monitored by RNA gel blot analysis as described previously (4). For luciferase assays, 0.1 ml of reporter strain culture was resuspended in 0.9 ml fresh medium and supplemented with decanal to a final concentration of 1 mM. Light emission by bioluminescence was recorded every 5 s in a photomultiplier-based luminometer (Lumat LB9501; Berthold). The mean value of five data points around the maximum of the peak was used as the luminescence output. All readings were normalized to the optical density of the cultures at 660 nm. Measurements were performed three times using independent cultures.

Semiquantitative reverse transcription (RT)-PCR was performed according to the protocol of the supplier using the Reverse-IT-One-Step-RT-PCR Kit (AB Gene, Hamburg, Germany); 20 ng/ml RNA template and 10 pmol of each primer were used per reaction. Reaction products were separated on 10% polyacrylamide gels and stained with ethidium bromide. Band intensities were quantified by the charge-coupled-device camera of a FluorS-Multiimager (Bio-Rad, München, Germany). The intensities of puf- and puc-specific products were normalized to the intensity of the rpoZ-specific PCR product. The primers used were as follows: for puf amplification, puf F and puf R; for puc amplification, puc F and puc R; for rpoZ amplification, rpoZ F and rpoZ R.

BChl quantification.

Photopigments were extracted with acetone-methanol (7:2 [vol/vol]) from cell pellets, and the BChl concentration was calculated using an extinction coefficient at 770 nm of 76 mM−1 cm−1 (8).

RESULTS

AppA/PpsR can transmit redox signals, but no blue-light signals, in R. capsulatus.

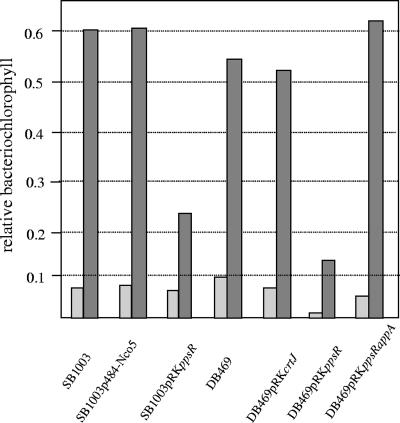

As closely related species, R. sphaeroides and R. capsulatus not only harbor photosynthesis genes with high similarity, but also share some of the regulatory pathways in the control of photosynthesis genes (11, 21, 22, 52). However, there are some marked differences in gene composition and gene regulation. One example is the blue-light-dependent repression of the puf and puc operons by the AppA/PpsR antirepressor/repressor system in R. sphaeroides that is not active in R. capsulatus, which lacks an AppA homologue (4). To test whether AppA/PpsR are sufficient to establish a blue-light-dependent signal chain, we studied puf and puc gene expression in R. capsulatus strains harboring the ppsR or ppsR/appA genes from R. sphaeroides on plasmids pRKppsR and pRKppsRappA, respectively. When we expressed the R. sphaeroides appA gene from the lac promoter on plasmid p484-Nco5 (16) in trans in R. capsulatus strain SB1003, no effect on pigment content (Fig. 1) or of blue light on puf and puc expression was observed (not shown). R. capsulatus harbors the CrtJ protein, which shares 53% identity with the PpsR protein of R. sphaeroides and represses photosynthesis genes at high oxygen tension. The CrtJ protein of R. capsulatus and the PpsR protein of R. sphaeroides are believed to bind to identical DNA target sequences (40, 44). Despite the high similarity of the two proteins, it is conceivable that CrtJ lacks residues that are important for interaction with AppA. We therefore decided to express both the plasmid-borne genes appA and ppsR in an R. capsulatus strain that lacks CrtJ (strain DB469). Under low oxygen tension, wild-type strain SB1003 and strain DB469 show a dark-red color due to the expression of photosynthesis genes and the formation of large numbers of pigment protein complexes, as indicated by the high BChl content (Fig. 1). At high oxygen tension, DB469 is more pigmented than the wild type but has much lower pigment content than at low oxygen tension. For full expression of photosynthesis genes, not only the lack of CrtJ repression, but also activation by RegA, is required (22). The similar increases in relative BChl levels in both strains after reduction of oxygen demonstrates that redox regulation of photosynthesis genes also takes place in the absence of CrtJ. Strain DB469pRKppsR shows a much lighter color under identical growth conditions and forms less BChl under aerobic conditions and after a shift to low oxygen tension than strain SB1003 or DB469pRKcrtJ (Fig. 1). Under all conditions tested, the relative BChl amounts in strain DB469pRKcrtJ were similar to that of the wild type (Fig. 1). This indicates that PpsR is a stronger repressor of photosynthesis gene expression than CrtJ and excludes the possibility that the small number of photosynthetic complexes in strain DB469pRKppsR results from stronger expression of the plasmid-carried ppsR gene than of the chromosomally carried crtJ gene in SB1003. The >5-fold increases in BChl after reduction of oxygen tension were very similar in strains DB469pRKppsR and DB469pRKcrtJ. The low level of BChl after the shift of oxygen tension in strain DB469pRKppsR suggests that repression of photosynthesis genes by PpsR occurs even at low oxygen tension. When plasmid pRKppsRappA was transferred into strain DB469, a significantly larger number of photosynthetic complexes accumulated at low oxygen tension, but also at high oxygen tension, than in strain DB469pRKppsR (Fig. 1). This strongly suggests that AppA can partially release the repressing effect of PpsR on photosynthesis genes in R. capsulatus, even at high oxygen tension. We conclude that PpsR and AppA together can function in redox signaling in R. capsulatus.

FIG. 1.

Relative BChl contents of various R. capsulatus strains. The strains were grown aerobically to an optical density of 0.4 (at 660 nm) and then shifted to low oxygen tension. At the time of oxygen reduction (t = 0; light gray) and after 5 h at low oxygen (dark gray) the BChl concentration was determined and divided by the optical density of the culture to give relative BChl levels. The results of a single experiment with strains growing in parallel are given. The experiment was repeated three times, and measurements varied by less than 10%.

We also quantified the levels of puf and puc mRNAs in strain DB469pRKppsRappA, semiaerobically grown in the dark or illuminated by blue light, by Northern blot analysis. In repeated experiments, we found no effect of blue light or little inhibition, not exceeding 15% puc or puf mRNA repression (data not shown). An R. sphaeroides appA mutant strain that expresses the appA gene in trans showed 73% inhibition of puc mRNA and 59% inhibition of puf mRNA by blue light (4). The CrtJ protein of R. capsulatus and the PpsR protein of R. sphaeroides are believed to bind to identical DNA target sequences (40, 44). The puc genes of both species harbor typical CrtJ/PpsR binding sites with almost identical sequences. The strong inhibition of puc expression in strain DB469pRKppsR and redox-dependent puc expression in strain DB469pRKppsRappA imply that PpsR binds to the R. capsulatus puc upstream region. Altogether, the results show that the AppA and PpsR proteins can function as redox regulators in R. capsulatus but are not sufficient to establish blue-light-dependent gene expression.

AppA/PpsR can establish redox-dependent, but not blue-light-dependent, gene repression in P. denitrificans.

We also transferred the plasmids for the expression of the appA/ppsR genes and puc reporter plasmids into the less closely related P. denitrificans to test whether PpsR/AppA would be functional in redox regulation or blue-light repression in this background. It was shown previously that the RNA polymerase of P. denitrificans is able to recognize the promoters of the R. sphaeroides genes (41). Plasmid pBBRpuclux was used as a reporter plasmid. Expression of the plasmid-carried R. sphaeroides puc genes was monitored by quantification of the luciferase activity in cultures kept in the dark or illuminated by blue light under semiaerobic conditions or grown at different oxygen tensions.

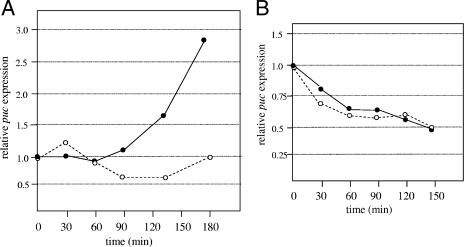

Compared to a strain expressing ppsR alone, expression of appA in combination with ppsR led to a >13-fold increase in puc-lux expression in aerobically grown cultures, suggesting that AppA is functional as an antagonist of PpsR in P. denitrificans (data not shown). When the P. denitrificans cells expressing appA/ppsR and harboring the reporter plasmid were subjected to a decrease in oxygen tension, little change in expression was observed within the first 60 min, followed by a marked increase in puc expression that was not detectable to the same extent in cultures kept under high oxygen tension (Fig. 2A). After 180 min, puc-lux expression in the shifted cultures was on average 2.8-fold higher than in the aerobically grown cultures. No oxygen-dependent change in puc-lux expression levels was observed when only PpsR was expressed in P. denitrificans (Fig. 2A). We conclude that some redox control of puc expression can be mediated by the AppA/PpsR system in Paracoccus.

FIG. 2.

(A) Response of puc expression to a drop in oxygen tension of Paracoccus denitrificans expressing the appA and ppsR genes (solid line) or the ppsR gene only (dotted line). Oxygen tension was reduced at time point zero, and expression of a puc-lux reporter gene was followed by determination of luminescence. The expression values at low oxygen were divided by the expression levels of a control kept at high oxygen tension, and the relative change in this value compared to time point zero (relative expression equals 1) was plotted. (B) Response of puc expression to blue-light illumination of Paracoccus denitrificans expressing the appA and ppsR genes (solid line) or the ppsR gene only (dotted line). Light illumination started at time point zero, and expression of a puc-lux reporter gene was followed by determination of luminescence. Expression values in the light were divided by expression levels of a control kept in the dark, and the relative change in this value compared to time point zero was plotted. Results for a single representative experiment are given. The experiments were repeated three or four times with similar results.

We observed a slight increase in luciferase-dependent light units in dark-grown control cultures of P. denitrificans expressing PpsR and AppA, as well as in cultures that were illuminated by blue light, with increasing optical density of the cultures. This increase was about two times less in cultures illuminated by blue light than in dark cultures (Fig. 2B). Thus, light did not inhibit puc expression in P. denitrificans but seemed to reduce a growth phase-dependent increase in expression. When we repeated the measurements with a P. denitrificans strain expressing PpsR but not AppA, we also observed an increase of light units with increasing optical density in the dark and in the light, with stronger increase in the dark (Fig. 2B). We conclude that AppA and PpsR in P. denitrificans cannot mediate blue-light-dependent puc repression.

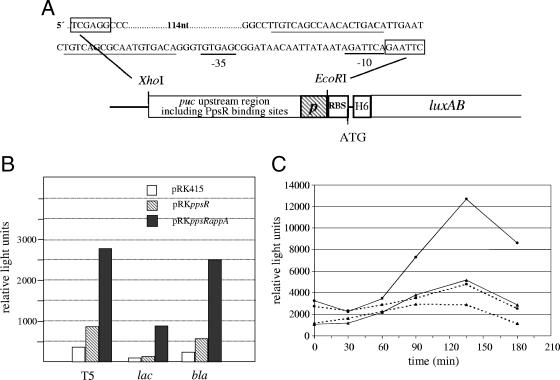

Expression of PpsR and AppA in E. coli.

Many Rhodobacter-type promoter sequences are markedly different from promoters of E. coli genes and are not recognized by the E. coli RNA polymerase. It was shown in the past that expression of Rhodobacter genes from the lac promoter or bla promoter results in good RNA yields in E. coli (25, 32, 43). We replaced the promoter of plasmid pQE31 (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) by the bla promoter or by the lac or T5 promoter. In front of these promoter sequences, we cloned two PpsR binding sites that were amplified from the region of R. sphaeroides upstream of puc. The distances from the PpsR binding sites to the −10 regions of the different promoters were similar to the distance in the R. sphaeroides puc promoter region. We then cloned the luxAB coding region into the resulting plasmids in order to monitor expression of the different promoters by quantitative luciferase assays. A schematic presentation of these constructs and the DNA sequence for the T5 promoter in combination with the PpsR binding sites is shown in Fig. 3A.

FIG. 3.

(A) Arrangement of the different elements on plasmids used to express the luciferase genes under the control of PpsR in E. coli. The sequences for the T5 promoter (underlined in black) and the PpsR binding sites (underlined in gray) are shown. p, promoter (T5, lac, or bla); RBS, ribosome binding site; H6, sequence providing an N-terminal His tag to the expressed protein. Restriction sites for XhoI and EcoRI are indicated in the scheme and boxed in the sequence. (B) Relative light units in E. coli strains (optical density of cultures, 0.4 at 600 nm) having the luxAB genes under the control of the T5, lac, or bla promoter. (C) Relative light units in E. coli harboring the lux genes under the control of the bla promoter after a shift from high to low oxygen tension at time point zero. Dashed lines, cultures shifted from high to low oxygen tension at time point zero; solid lines, cultures kept at high oxygen tension; dots, E. coli strain expressing appA and ppsR genes; triangles, E. coli strain expressing ppsR only. The results for a representative experiment are given. The experiments were repeated at least three times with similar results.

We determined the luciferase activity in E. coli strains harboring one of the three different reporter plasmids and expressing either ppsR or ppsR in combination with appA. We observed three- to eightfold-increased expression from all three promoters (lac, T5, and bla) when both proteins were present compared to the strains expressing PpsR only (Fig. 3B). We tested the effect of oxygen tension or blue light on the expression of the different promoters. As shown for the bla-lux fusion in Fig. 3C, expression increased after a shift to low oxygen tension. An even stronger increase was observed, however, in cultures at high oxygen tension. When the expression level was calibrated to the cell density, we still observed an increase in expression over time. This indicates that the expression depends on the growth phase of the cultures but is not under redox control. Growth phase-dependent luciferase activity was also observed when the reporter plasmid was present together with the cloning vector pRK415 (without ppsR or appA), supporting this assumption (data not shown). Like reduction of oxygen tension, illumination by blue light did not have a specific effect on expression from any of the tested promoters (data not shown).

Recently, we revealed that signal transmission by AppA requires a heme cofactor (Y. Han, M. Meyer, M. Keusgen, and G. Klug, submitted for publication). The levels of proteins with bound heme can be increased if E. coli is grown in the presence of aminolevulinic acid (49). Therefore, we tested the effect of this heme precursor on the luciferase expression in our test strains. While the addition of 1 mM aminolevulinic acid had little effect on luciferase expression, addition of 10 mM aminolevulinic acid strongly increased expression (about 20-fold) from the bla promoter when PpsR and AppA were present. However, even in the presence of 10 mM aminolevulinic acid, no redox regulation of the bla promoter was detected in the E. coli system (data not shown).

Light-dependent repression of photosynthesis genes in R. sphaeroides under semiaerobic conditions depends on the presence of the PrrA response regulator.

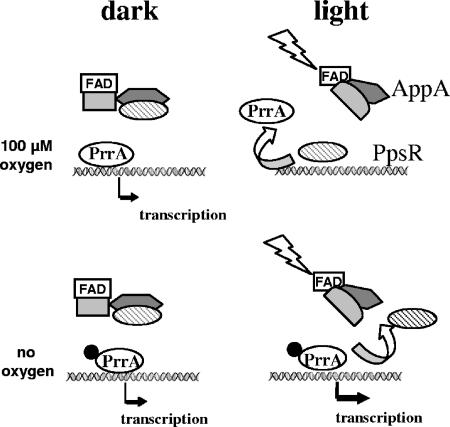

Redox-dependent expression of photosynthesis genes in R. sphaeroides is not only mediated by the AppA/PpsR system, but also strongly depends on the PrrB/PrrA two-component system (42). We unraveled earlier that the control by light under anaerobic conditions in R. sphaeroides is the consequence of the interplay of AppA/PpsR and the PrrB/PrrA two-component system (24). Since it was not possible to establish light signaling by the AppA/PpsR system in other bacteria, we assumed that such interplay might also be involved in blue-light regulation at intermediate oxygen tension. To test this hypothesis, we quantified the effects of blue light on puf and puc expression in semiaerobically grown strain PrrA2, which lacks PrrA, and strain PrrB1, which lacks PrrB. puf and puc mRNA levels in strain PrrB1 were quantified by Northern blot analysis and were clearly repressed by blue light to an extent similar to that observed in the isogenic wild-type strain (Fig. 4). puf and puc mRNA levels in strain PrrA2 were too low for Northern blot detection. Semiquantitative RT-PCR revealed that in the absence of PrrA neither puf nor puc mRNA levels vary under blue-light illumination (Fig. 4). The role of PrrA in blue-light regulation at intermediate oxygen tension is discussed below, and Fig. 5 presents a model for the interplay of AppA/PpsR and PrrA at different oxygen concentrations.

FIG. 4.

Light-dependent inhibition of puf (dotted lines) and puc (solid lines) genes in R. sphaeroides strains lacking either PrrB or PrrA. The inhibition was calculated by the formula 100 [1 − (band intensity in the light/band intensity in the dark)]. Gene expression in strain PrrB1 was quantified by Northern blot analysis; gene expression in strain PrrA2 was quantified by semiquantitative RT-PCR. The quantification for the gels is shown.

FIG. 5.

Model for the coordinated regulation of photosynthesis gene expression in R. sphaeroides by AppA/PpsR and the response regulator PrrA. At low oxygen tension, strong activation by (phosphorylated?) PrrA occurs, even if PpsR is not bound to AppA during illumination. At intermediate oxygen tension, some activation by (unphosphorylated?) PrrA occurs in the dark. In the light, PpsR that is not bound to AppA replaces PrrA on the DNA and prevents activation by PrrA.

DISCUSSION

In R. sphaeroides, the AppA and PpsR proteins transmit both redox and light signals to control the expression of photosynthesis genes in response to external stimuli. We tested whether these two proteins are also sufficient for redox and light signaling in other bacteria and whether AppA could confer light regulation on R. capsulatus, which contains a PpsR homologue but lacks AppA. Expression of appA in the R. capsulatus wild-type background did not result in light-regulated formation of photosynthetic complexes. Although CrtJ and PpsR share 53% sequence identity, they appear to act differently on gene expression. CrtJ undergoes a dithiol-disulfide switch in response to redox signals. Oxidized CrtJ has lower affinity for DNA, and repression is released (37, 44). Redox-dependent binding of PpsR has been demonstrated in vitro (7, 37). However, the redox state of PpsR appears not to change in the cell with varying redox and light conditions (7; unpublished data). This strongly suggests that release of PpsR repression requires binding to its antagonist, AppA. The data we present here support the view that PpsR alone is sufficient for transmission of redox signals in R. capsulatus and that it is a stronger repressor than CrtJ under both high and low oxygen tension. This is also underlined by recent redox titration experiments that revealed a much more negative Em (midpoint potential) value for the dithiol/disulfide-switch in PpsR (Em = −320 mV) than in CrtJ (Em = −180 mV) (29). Photosystem formation in an R. capsulatus strain lacking CrtJ but expressing ppsR is significantly repressed, even at low oxygen tension. Repression at low oxygen tension is released in the presence of AppA (Fig. 1).

Blue-light repression of photosynthesis genes in R. capsulatus cannot be established by AppA and PpsR. In R. sphaeroides, blue-light repression of photosynthesis genes at intermediate oxygen tension depends on the presence of the response regulator and activator of transcription PrrA, while inactivation of the corresponding histidine kinase PrrB has virtually no effect (Fig. 4). In the absence of PrrA, expression of puf and puc genes at intermediate oxygen tension is very low, and no further repression can be observed in the light, as detected by RT-PCR (Fig. 4). As outlined in our model (Fig. 5), we suggest that at an intermediate oxygen level, photosynthesis gene expression is activated by PrrA to some extent. In the light, PpsR prevents this activation by PrrA. PrrB is not required for this activation, indicating either that unphosphorylated PrrA can activate transcription to some extent or that PrrA is also phosphorylated independently of PrrB. Earlier studies from our laboratory showed that RegA, the PrrA homologue in R. capsulatus, is able to bind DNA in its unphosphorylated state (26, 30). We showed before that under anaerobic conditions white light can activate photosynthesis gene expression via the PrrB/PrrA system (24). Under these conditions, PrrA is believed to counteract the repressing effect of PpsR (Fig. 5). We suggest a redox-dependent balance between DNA binding and activation by PrrA and DNA binding of PpsR. No experimental data are available for the exact PrrA binding sequence within the puc and puf promoter regions of R. sphaeroides. However, DNase I footprint protection analysis located binding of the PrrA homologue RegA at the puc promoter of R. capsulatus, centered around 60 bp upstream of the transcription initiation site (9, 30). This interferes with the DNA sequence known to be protected from DNase I digestion by CrtJ (10) and partly covers the CrtJ recognition site (TGTN12TGT) spanning the −35 promoter region (10). Competition of CrtJ and RegA for DNA binding at the puc promoter was also observed in vitro (3). The factors that determine whether activation by PrrA (at very low oxygen tension) or inhibition by PpsR (at intermediate oxygen tension in the light) prevails need further elucidation. It is conceivable that the phosphorylation state of PrrA is one of these factors.

Our data show that redox-dependent signaling by AppA to PpsR is established in R. capsulatus and in P. denitrificans, both of which harbor PrrA homologues. However, under semiaerobic conditions, AppA/PpsR fail to transmit light signals in these strains. A higher binding affinity of the PrrA homologues to their target DNAs might be responsible for this observation. If PpsR, which is released from AppA during illumination at intermediate oxygen tension, fails to replace the more tightly bound PrrA homologues, no blue-light-dependent gene repression will occur.

It appears that the presence of AppA interferes with PpsR repression even at high oxygen tension in E. coli, and no redox-dependent change in AppA-PpsR interaction occurs. Based on earlier reports, it is unlikely that the cytoplasmic redox potential of Rhodobacter is less reduced than that of E. coli (37, 53). We demonstrated recently that a heme cofactor attached to AppA is involved in redox and light signaling (Han et al., submitted). It is conceivable that binding of molecular oxygen is involved in AppA redox signaling and that the binding rates of heme to AppA or of oxygen to the heme cofactor of AppA in E. coli and Rhodobacter differ. The promoters that we used for the reporter constructs in E. coli do not contain any putative PrrA binding site and are not known to be under any redox control. The interplay between AppA/PpsR and PrrA, which, according to our model, is required for light signaling, can therefore not be established. Surprisingly, the expression of PpsR alone did lead to a slight activation of the T5 and bla promoters in E. coli, indicating that it does not act as a repressor in E. coli. In Rubrivivax gelatinosus, PpsR was shown to act as an aerobic repressor of the crtJ gene but as an activator for the expression of pucBA (50). Differences in the PpsR binding sites were suggested as the reason for different PpsR actions. Our results suggest that the promoter region itself may be responsible for differences in PpsR action and that AppA may not only release repression by PpsR, but also enhance activation. Based on the results with the PrrA mutant, the model shown in Fig. 5 postulates that PpsR in R. sphaeroides prevents activation of photosynthesis genes by PrrA under certain conditions but does not repress basal transcription.

We conclude from this study that competition between the PpsR repressor and the PrrA activator is required for light-dependent gene expression at intermediate oxygen tension. This needs to be analyzed in vivo to further elucidate light signaling in R. sphaeroides.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 January 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson, S., V. Dragnea, S. Masuda, J. Ybe, K. Moffat, and C. Bauer. 2005. Structure of a novel photoreceptor, the BLUF domain of AppA from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Biochemistry 44:7998-8005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bollivar, D. W., J. Y. Suzuki, J. T. Beatty, J. M. Dobrowolski, and C. E. Bauer. 1994. Directed mutational analysis of bacteriochlorophyll a biosynthesis in Rhodobacter capsulatus. J. Mol. Biol. 237:622-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowman, W. C., S. Du, C. E. Bauer, and R. G. Kranz. 1999. In vitro activation and repression of photosynthesis gene transcription in Rhodobacter capsulatus. Mol. Microbiol. 33:429-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braatsch, S., M. Gomelsky, S. Kuphal, and G. Klug. 2002. A single flavoprotein, AppA, integrates both redox and light signals in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Mol. Microbiol. 45:827-836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braatsch, S., O. V. Moskvin, G. Klug, and M. Gomelsky. 2004. Responses of the Rhodobacter sphaeroides transcriptome to blue light under semiaerobic conditions. J. Bacteriol. 186:7726-7735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casadaban, M. J., J. Chou, and S. N. Cohen. 1980. In vitro gene fusions that join an enzymatically active beta-galactosidase segment to amino-terminal fragments of exogenous proteins: Escherichia coli plasmid vectors for the detection and cloning of translational initiation signals. J. Bacteriol. 143:971-980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho, S. H., S. H. Youn, S. R. Lee, H. S. Yim, and S. O. Kang. 2004. Redox property and regulation of PpsR, a transcriptional repressor of photosystem gene expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Microbiology 150:697-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clayton, R. K., and B. J. Clayton. 1981. B850 pigment-protein complex of Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides: extinction coefficients, circular dichroism, and the reversible binding of bacteriochlorophyll. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 78:5583-5587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du, S., T. H. Bird, and C. E. Bauer. 1998. DNA binding characteristics of RegA. A constitutively active anaerobic activator of photosynthesis gene expression in Rhodobacter capsulatus. J. Biol. Chem. 273:18509-18513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elsen, S., S. N. Ponnampalam, and C. E. Bauer. 1998. CrtJ bound to distant binding sites interacts cooperatively to aerobically repress photopigment biosynthesis and light harvesting II gene expression in Rhodobacter capsulatus. J. Biol. Chem. 273:30762-30769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elsen, S., L. R. Swem, D. L. Swem, and C. E. Bauer. 2004. RegB/RegA, a highly conserved redox-responding global two-component regulatory system. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68:263-279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eraso, J. M., and S. Kaplan. 1996. Complex regulatory activities associated with the histidine kinase PrrB in expression of photosynthesis genes in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. J. Bacteriol. 178:7037-7046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eraso, J. M., and S. Kaplan. 1995. Oxygen-insensitive synthesis of the photosynthetic membranes of Rhodobacter sphaeroides: a mutant histidine kinase. J. Bacteriol. 177:2695-2706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eraso, J. M., and S. Kaplan. 1994. PrrA, a putative response regulator involved in oxygen regulation of photosynthesis gene expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 176:32-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gauden, M., S. Yeremenko, W. Laan, I. H. van-Stokkum, J. A. Ihalainen, R. van-Grondelle, K. J. Hellingwerf, and J. T. Kennis. 2005. Photocycle of the flavin-binding photoreceptor AppA, a bacterial transcriptional antirepressor of photosynthesis genes. Biochemistry 44:3653-3662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gomelsky, M., and S. Kaplan. 1995. appA, a novel gene encoding a trans-acting factor involved in the regulation of photosynthesis gene expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. J. Bacteriol. 177:4609-4618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomelsky, M., and S. Kaplan. 1995. Genetic evidence that PpsR from Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1 functions as a repressor of puc and bchF expression. J. Bacteriol. 177:1634-1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gomelsky, M., and S. Kaplan. 1997. Molecular genetic analysis suggesting interactions between AppA and PpsR in regulation of photosynthesis gene expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. J. Bacteriol. 179:128-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gomelsky, M., and S. Kaplan. 1998. AppA, a redox regulator of photosystem formation in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1, is a flavoprotein. Identification of a novel Fad binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 273:35319-35325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gomelsky, M., and G. Klug. 2002. BLUF: a novel FAD-binding domain involved in sensory transduction in microorganisms. Trends Biochem. Sci. 27:497-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gregor, J., and G. Klug. 2002. Oxygen-regulated expression of genes for pigment binding proteins in Rhodobacter capsulatus. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 4:249-253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gregor, J., and G. Klug. 1999. Regulation of bacterial photosynthesis genes by oxygen and light. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 179:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han, Y., S. Braatsch, L. Osterloh, and G. Klug. 2004. A eukaryotic BLUF domain mediates light-dependent gene expression in the purple bacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:12306-12311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Happ, H. N., S. Braatsch, V. Broschek, L. Osterloh, and G. Klug. 2005. Light-dependent regulation of photosynthesis genes in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1 is coordinately controlled by photosynthetic electron transport via the PrrBA two-component system and the photoreceptor AppA. Mol. Microbiol. 58:903-914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heck, C., A. Balzer, O. Fuhrmann, and G. Klug. 2000. Initial events in the degradation of the polycistronic puf mRNA in Rhodobacter capsulatus and consequences for further processing steps. Mol. Microbiol. 35:90-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hemschemeier, S. K., M. Kirndörfer, M. Hebermehl, and G. Klug. 2000. DNA binding of wild type RegA protein and its differential effect on the expression of pigment binding proteins in Rhodobacter capsulatus. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2:235-243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iseki, M., S. Matsunaga, A. Murakami, K. Ohno, K. Shiga, K. Yoshida, M. Sugai, T. Takahashi, T. Hori, and M. Watanabe. 2002. A blue-light-activated adenylyl cyclase mediates photoavoidance in Euglena gracilis. Nature 415:1047-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keen, N. T., S. Tamaki, D. Kobayashi, and D. Trollinger. 1988. Improved broad-host-range plasmids for DNA cloning in gram-negative bacteria. Gene 70:191-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim, S. K., J. T. Mason, D. B. Knaff, C. E. Bauer, and A. T. Setterdahl. 2006. Redox properties of the Rhodobacter sphaeroides transcriptional regulatory proteins PpsR and AppA. Photosynth. Res. 89:89-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirndörfer, M., A. Jäger, and G. Klug. 1998. Integration host factor affects the oxygen-regulated expression of photosynthesis genes in Rhodobacter capsulatus. Mol. Gen. Genet. 258:297-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klug, G., and G. Drews. 1984. Construction of a gene bank of Rhodopseudomonas capsulata using a broad host range DNA cloning system. Arch. Microbiol. 139:319-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klug, G., S. Jock, and R. Rothfuchs. 1992. The rate of decay of Rhodobacter capsulatus-specific puf mRNA segments is differentially affected by RNase E activity in Escherichia coli. Gene 121:95-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kraft, B. J., S. Masuda, J. Kikuchi, V. Dragnea, G. Tollin, J. M. Zaleski, and C. E. Bauer. 2003. Spectroscopic and mutational analysis of the blue-light photoreceptor AppA: a novel photocycle involving flavin stacking with an aromatic amino acid. Biochemistry 42:6726-6734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kunert, A., M. Hagemann, and N. Erdmann. 2000. Construction of promoter probe vectors for Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 using the light-emitting reporter systems Gfp and LuxAB. J. Microbiol. Methods 41:185-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laan, W., M. A. van der Horst, I. H. van Stokkum, and K. J. Hellingwerf. 2003. Initial characterization of the primary photochemistry of AppA, a blue-light-using flavin adenine dinucleotide-domain containing transcriptional antirepressor protein from Rhodobacter sphaeroides: a key role for reversible intramolecular proton transfer from the flavin adenine dinucleotide chromophore to a conserved tyrosine? Photochem. Photobiol. 78:290-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Masuda, S., and C. E. Bauer. 2002. AppA is a blue light photoreceptor that antirepresses photosynthesis gene expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Cell 110:613-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Masuda, S., C. Dong, D. Swem, A. T. Setterdahl, D. B. Knaff, and C. E. Bauer. 2002. Repression of photosynthesis gene expression by formation of a disulfide bond in CrtJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:7078-7083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Masuda, S., K. Hasegawa, and T. A. Ono. 2005. Adenosine diphosphate moiety does not participate in structural changes for the signaling state in the sensor of blue-light using FAD domain of AppA. FEBS Lett. 579:4329-4332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Masuda, S., K. Hasegawa, and T. A. Ono. 2005. Tryptophan at position 104 is involved in transforming light signal into changes of beta-sheet structure for the signaling state in the BLUF domain of AppA. Plant Cell Physiol. 46:1894-1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moskvin, O. V., L. Gomelsky, and M. Gomelsky. 2005. Transcriptome analysis of the Rhodobacter sphaeroides PpsR regulon: PpsR as a master regulator of photosystem development. J. Bacteriol. 187:2148-2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Gara, J. P., M. Gomelsky, and S. Kaplan. 1997. Identification and molecular genetic analysis of multiple loci contributing to high-level tellurite resistance in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4713-4720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oh, J. I., and S. Kaplan. 2001. Generalized approach to the regulation and integration of gene expression. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1116-1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pollich, M., S. Jock, and G. Klug. 1993. Identification of a gene required for the oxygen-regulated formation of the photosynthetic apparatus of Rhodobacter capsulatus. Mol. Microbiol. 10:749-757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ponnampalam, S. N., and C. E. Bauer. 1997. DNA binding characteristics of CrtJ. A redox-responding repressor of bacteriochlorophyll, carotenoid, and light harvesting-II gene expression in Rhodobacter capsulatus. J. Biol. Chem. 272:18391-18396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sambrook, J., and D. Russel. 2001. Molecular cloning, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 46.Shimada, H., K. Iba, and K. I. Takamiya. 1992. Blue-light irradiation reduces the expression of puf and puc operons of Rhodobacter sphaeroides under semi-aerobic conditions. Plant Cell Physiol. 33:471-475. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simon, R., M. O'Connell, M. Labes, and A. Puhler. 1986. Plasmid vectors for the genetic analysis and manipulation of rhizobia and other gram-negative bacteria. Methods Enzymol. 118:640-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sistrom, W. R. 1977. Transfer of chromosomal genes mediated by plasmid r68.45 in Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 131:526-532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smart, J. L., and C. E. Bauer. 2006. Tetrapyrrole biosynthesis in Rhodobacter capsulatus is transcriptionally regulated by the heme-binding regulatory protein, HbrL. J. Bacteriol. 188:1567-1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Steunou, A. S., C. Astier, and S. Ouchane. 2004. Regulation of photosynthesis genes in Rubrivivax gelatinosus: transcription factor PpsR is involved in both negative and positive control. J. Bacteriol. 186:3133-3142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taylor, D. P., S. N. Cohen, W. G. Clark, and B. L. Marrs. 1983. Alignment of genetic and restriction maps of the photosynthesis region of the Rhodopseudomonas capsulata chromosome by a conjugation-mediated marker rescue technique. J. Bacteriol. 154:580-590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zeilstra-Ryalls, J. H., and S. Kaplan. 2004. Oxygen intervention in the regulation of gene expression: the photosynthetic bacterial paradigm. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 61:417-436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zheng, M., F. Aslund, and G. Storz. 1998. Activation of the OxyR transcription factor by reversible disulfide bond formation. Science 279:1718-1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]