Abstract

We have designed, tested, and validated synthetic DNA molecules that may be used as reference standard controls in the simultaneous detection of mutations in one or more genes. These controls consist of a mixture of oligonucleotides (100 to 120 bases long) each designed for the detection of one or more disease-causing mutation(s), depending on the proximity of the mutations to one another. Each control molecule is identical to 80 to 100 bases that span the targeted mutations. In addition, each oligonucleotide is tagged at the 5′ and 3′ ends with distinct nucleic acid sequences that allow for the design of complementary primers for polymerase chain reaction amplification. We designed the tags to amplify control molecules comprising 32 CFTR mutations, including the American College of Medical Genetics minimum carrier screening panel of 23, with one pair of primers in a single tube. We tested the performance of these controls on many platforms including the Applied Biosystems/Celera oligonucleotide ligation assay and the Tm Bioscience Tag-It platforms. All 32 mutations were detected consistently. This simple methodology allows for maximum flexibility and rapid implementation. It has not escaped our notice that the design of these molecules makes possible the production of similar controls for virtually any mutation or sequence of interest.

Good laboratory practices, government agencies, and standards organizations require diagnostic laboratories to use stringent quality controls (QCs). The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (formerly the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards) suggests accreditation guidelines that include calibrating equipment against control samples and performing tests of patient samples in tandem with consistent references (Table 1). Other organizations also recommend standardized clinical procedures often requiring updated (nonexpired) and well-inventoried supplies of clinical reference reagents and controls.2 According to the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988, which applies to more than 175,000 laboratory entities, control references must be tested in conjunction with each analysis of a patient sample.3,4 The College of American Pathologists and the American College of Medical Genetics also mandate comparison with references during each patient test. It is critical that controls be used in a manner that provides comprehensive evaluation of every component of these highly complex procedures and reagent mixtures. The need for these controls became particularly acute with the widespread use of high-complexity and high-volume molecular tests such as cystic fibrosis (CF) testing.

Table 1.

Useful Resources for Laboratory Standards and Quality Control

| Standards | References |

|---|---|

| National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards: Molecular diagnostic methods for genetic diseases. Approved guidelines. | 1 |

| New York State Department of Health Laboratory Standards | http://www.wadsworth.org/labcert/clep/Survey/files/standardseffective12106.pdf (accessed 12/07/06) |

| The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and American College of Medical Genetics: Preconception and prenatal carrier screening for cystic fibrosis, clinical and laboratory guidelines. | 2 |

| Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Clinical laboratory improvement amendments of 1988; Final rule. | 3 |

| Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Genetic Testing under CLIA | 4 |

| College of American Pathologists Checklist | http://www.cap.org/apps/docs/laboratory_accreditation/ checklists/molecular_pathology_october2005.pdf (accessed 12/07/06) |

| American College of Medical Genetics Standards and Guidelines for Clinical Genetics Laboratories 2006 Edition | http://www.acmg.net/Pages/ACMG_Activities/stds-2002/stdsmenu-n.htm (accessed 12/07/06) |

| U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration: Center for Devices and Radiological Health, Center for Biologic Evaluation and Research: Guidance on Informed Consent for In Vitro Diagnostic Device Studies Using Leftover Human Specimens that are Not Individually Identifiable: April 25, 2006. | http://www.fda.gov/cdrh/oivd/guidance/1588.html (accessed 12/07/06) |

Current practice consists of using a DNA-negative or blank control, a genomic DNA sample that serves as wild-type or mutation-negative control, and one or more genomic DNA samples each with one or two mutations that serve as mutation-positive control. Until recently, many of these genomic DNA samples of clinical significance were not available for use in clinical testing and QC. Furthermore, the use of genomic DNA controls to evaluate every mutation in every test run of these complex assays was not realistic because of practical and financial considerations. Although the 23-mutation panel, 394delTT, and I148T are available from the Coriell Cell Repository in the form of cell lines or genomic DNA, 1078delT, 347H, 549N, 549R, 3876delA, and 3905insT are still not available. In addition, the Food and Drug Administration recently released guidance documents on the uses of residual clinical specimens that may limit the activities of public cell banks (Table 1). Although most of the samples are now available, the cost of running the full genomic panel in every run remains impractical. As a compromise, laboratories usually rotate subsets of these genomic mutant controls. This strategy requires multiple runs to evaluate the full complement of mutation-specific reagents. In response to these limitations, we and others have developed synthetic controls.

We designed, developed, validated, and used chemically synthesized reference standards and combined them into mixtures producing synthetic controls that carry multiple mutations for one or multiple genes in a single reaction mixture. Because each control molecule is composed of a small synthetic nucleic acid fragment, it is possible to evaluate multiple mutations by mixing these control oligonucleotides in a single tube, instead of the dozens of tubes that would be required if mutant genomic DNA controls were used. The design of these molecules makes possible the production of similar controls for virtually any mutation or sequence of interest.

Materials and Methods

Oligonucleotide Design

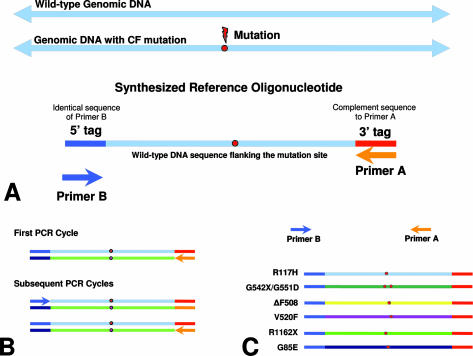

Each standard synthetic control molecule was designed to contain three distinct regions: a 5′ tag, a reference sequence that is identical to ∼80 to 100 bases spanning and including a mutation of interest, and a 3′ tag (Figure 1A). The tags allow primer binding for subsequent PCR amplification (Figure 1B). We applied this design to the CFTR gene. Each reference sequence for the CFTR mutation controls is designed based on the published literature and genomic reference sequence NT007933 obtained from GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/GenBank/index.html) and The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Cystic Fibrosis Mutation Database (http://www.genet.sickkids.on.ca/cftr).5,6,7,8 Modified genomic sequences were also designed to incorporate more than one mutation on a contiguous standard reference sequence (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Design methodology. A: Each synthetic reference standard is designed to be amplified with a single primer pair that anneals to each primer tag region. Because the oligonucleotides are single stranded, the first round of PCR amplification generates a complementary strand for each synthetic oligonucleotide. B: After this initial cycle, the remaining PCR cycles amplify the DNA fragments in a standard manner. Reference oligonucleotides are designed for each mutation of interest. In some cases, more than one mutation may be incorporated within the same reference oligonucleotide (red circles). C: Assorted mixtures of the various reference oligonucleotides are combined and amplified using a single primer pair to produce synthetic controls carrying one or dozens of mutations that may be visualized in a single reaction tube.

Sequencing of Reference Oligonucleotides and Performance Evaluation

Each standard synthetic control molecule was obtained from Sigma-Genosys (St. Louis, MO), diluted with deionized water and sequenced with the Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit (Perkin Elmer Applied Biosystems Division, Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The performance of each control molecule was then tested in a separate CFv3.0 PCR/OLA reaction to determine relative amplification efficiency. Each reaction was also used to identify reference sequences producing cross-talk, a phenomenon in which the wild-type sequence surrounding one mutant oligonucleotide overlaps with another mutation site resulting in multiple signals from a single oligonucleotide.

Combining of Reference Oligonucleotides into a Multiplex Control Mixture

Control mixtures were designed by combining multiple reference oligonucleotides with the appropriate PCR primer pair. Template concentration for each reference oligonucleotide and the PCR primers was determined by prior reference evaluation experiments and additional titration experiments using analyte-specific reagents from the CFv3.0 assay. The control mixes were designed to produce signal intensities at a level equal or less than that obtained from a standard genomic DNA control. The control design and mix parameters have been evaluated for nearly 4 years (since November 2002). During this time, these controls were used in more than 350 test runs on the ABI CF v3.0 PCR/OLA platform (Perkin Elmer Applied Biosystems Division) in conjunction with genomic DNA controls.

Evaluation of Controls on Distinct Platforms

Control mixes, test reagents, and standard test procedures were modified to determine the performance of the synthetic controls compared with genomic DNA samples subjected to the same changes on distinct platforms. These modifications included titrations of template DNA concentration, adjustment of test reactions to decrease the concentration of primers and probes, and alterations of additional reaction components that could negatively impact the performance of the CF assay. Aliquots of 5 μl of the synthetic control mixture were used in place of genomic DNA samples for the ABI CFv3.0 PCR/OLA platform and on the Tm Bioscience TAG-IT platform (Toronto, ON, Canada).

Results

We have designed, developed, tested, and used groups of synthesized oligonucleotides as reference standards for complex molecular assays. Figure 1A illustrates the general design of each oligonucleotide used in a typical reference standard mix. Each oligonucleotide contains a mutation of interest flanked by wild-type sequence. These distinct mutant oligonucleotides are then combined into a mix that can be amplified in a standard PCR reaction (Figure 1, B and C). By designing each mutant reference oligonucleotide as a short gene fragment, we minimized the presence of wild-type sequences that could overlap and interact with the test-specific primers and probes. This overlap causes multiple signals to be generated from one reference oligonucleotide. In addition to generating the expected mutation-specific signal, the same oligonucleotide produces a wild-type signal for the overlapping mutation as well. This is the result of hotspot regions within the CFTR gene in which several mutations are within just a few bases of one another. The mutant oligonucleotides for the ΔI507, ΔF508, S549R, S549N, G551D, R553X, G542X, G85E, 394delTT, and 3905insT mutations are all capable of generating wild-type signals at varying degrees within these assays (Figures 2and 3).

Figure 2.

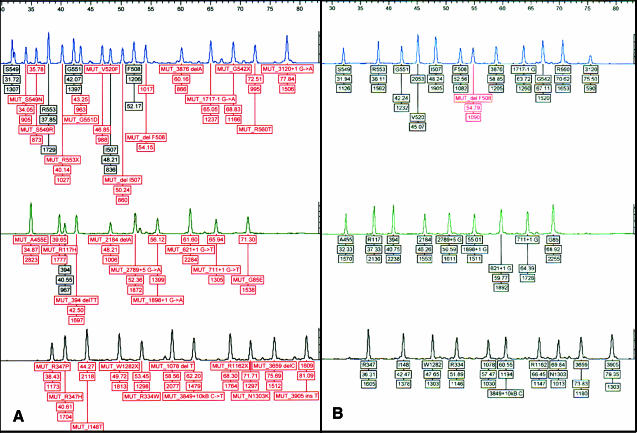

PCR/OLA data. This is a comparison between the synthetic control mixture (A) and a heterozygous ΔF508 genomic control (B) with the Celera Diagnostics CFv3.0 PCR/OLA ASR reagents on an ABI 3100 genetic analyzer.

Figure 3.

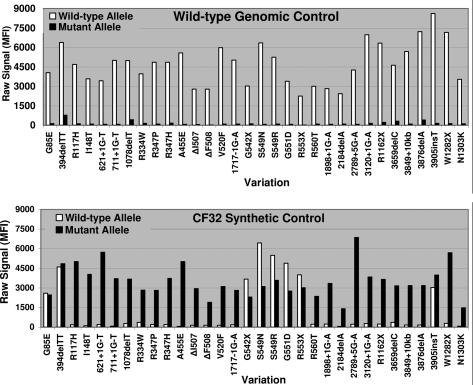

TAG-IT data. Raw data from the CF32 synthetic control and a wild-type genomic DNA sample are analyzed on the TAG-IT platform using the 40 + 4 CF ASR set. This assay does not generate a F508 wild-type signal, whereas it does produce wild-type signal for G85, G542, and 3905. These discrepancies most likely reflect the distinctiveness of the platforms themselves (ABI’s OLA approach versus Tm Bioscience’s allele-specific primer extension) instead of the performance of the controls.

A mixture of oligonucleotides (CF32 control) consisting of the American College of Medical Genetics 23-mutation panel, 394delTT, I148T, 1078delT, 347H, 549N, 549R, 3876delA, and 3905insT was designed to mimic 32 distinct alleles of CFTR. This design allows all 32 mutations to be evaluated in a single reaction tube. Typical data output from the CF PCR/OLA platform is shown in Figure 2. The CF32 control was also tested on the TAG-IT platform and performed as shown in Figure 3.

Discussion

We have designed, tested, and validated synthetic DNA molecules and used them as reference standard controls for the simultaneous detection of 32 distinct sequence variations in CFTR in a single reaction tube. This synthetic control mix (CF32 control) has applications for many platforms and was tested successfully on the Applied Biosystems/Celera OLA CF, Tm Bioscience array, Roche Gold (Indianapolis, IN), Sequenom (San Diego, CA), Asuragen (Austin, TX), and Third Wave Technologies Inplex assay (Madison, WI).

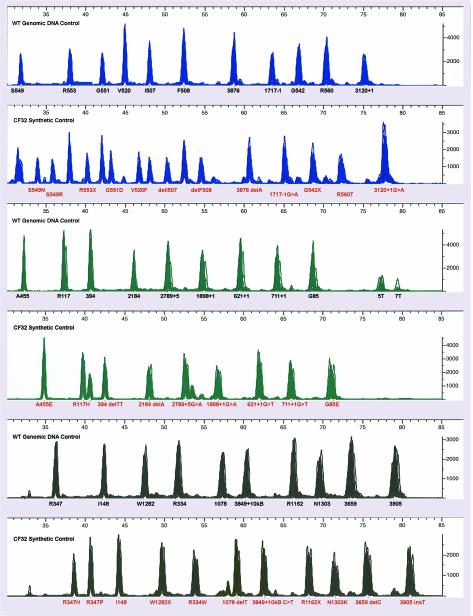

These synthetic controls were developed as reference material for evaluating reagents that are specific for multiple mutations in a single tube and performed appropriately in more than 350 test runs throughout a 3-year period on the Applied Biosystems/Celera OLA CF platform. Although the relative fluorescent intensity for the control parallels the relative intensity of the genomic controls and that of patients, there is run-to- run variation related to PCR and OLA efficiency and master mix preparation. The controls provide very consistent peak heights within the run, and unless there is a problem that affects the genomic controls and patient samples as well, the synthetic control generates all of the expected peaks and produces an electrophoretic fingerprint that can be compared between test runs (Figure 4). In each of six runs of 350 test runs, a single mutant peak was not labeled. In these cases, the software deselects a peak based on the relative height of the adjacent peaks. Although the electropherogram profile looks nearly identical to an acceptable run, the ratio shifts just enough to drop below the cutoff. This was observed once for each of delF508, delI507, G551D, R553X, and twice with S549N because of the cross talk occurring from wild-type sequences bordering these mutations in the exon 11 hotspot region. Software genotyping settings automatically deselect peaks if the preceding peak is 125% higher than its corresponding mutant. This built-in safety feature for stringent software genotyping conflicts with this synthetic control that has multiple mutant peaks. Mixing mutant oligonucleotides with genomic wild-type DNA samples exacerbates the problem of elevated wild-type peaks corresponding to these hotspot regions. Therefore, mixing the synthetic oligonucleotide control with genomic DNA as a way to identify all mutant and wild-type peaks was not pursued. Furthermore, the wild-type genomic control already evaluates the common and wild-type probes so additional peaks in the synthetic control are not necessary.

Figure 4.

Reproducibility study. Electropherograms from 100 distinct runs of each of the CF32 control and a wild-type genomic DNA control. These runs are aligned and evaluated within a single Genotyper project file. The aligned electropherograms represent data compiled from 100 consecutive runs performed during standard testing performed at the Sacred Heart Medical Center clinical laboratory throughout the last year.

Experiments testing longevity and stability were conducted throughout a 3-year period. Control lots generated reproducible results well beyond 2 years when maintained frozen at −20°C, beyond 6 months at 4°C, and several weeks at room temperature (data not shown). Although these time limitations reflect the length of our studies, they do not represent the stability limit of the controls.

These controls were validated on two distinct commercial platforms (the Applied Biosystems/Celera CFv3.0 PCR/OLA ASR and the Tm Bioscience TAG-IT array). All 23 mutations in the American College of Medical Genetics minimum mutation panel9,10 were detected consistently with both platforms. This simple methodology allows for maximum flexibility, rapid implementation, and multiplex testing of multiple mutations in a single tube. The design of these molecules makes possible the production of similar controls for virtually any mutation or sequence of interest.

Although these synthetic controls provide several advantages over genomic DNA controls, the latter are still critical to create a comprehensive QC for these complex tests. A purely genomic control approach to QC that would control for every mutation detected in a CF assay is not feasible. Such an approach will use an inordinate amount of reagents and would result in a testing procedure that is not economically justifiable or practically realistic. Instead, current QC methodologies rely on testing a small subset of mutations from genomic controls and leave the majority of mutation-specific reagents untested. By using a combined genomic/synthetic approach that takes advantage of our design, we have built on the strengths of genomic DNA controls by adding a synthetic component to the QC testing strategy. A comprehensive control set consisting of a genomic wild-type DNA, our synthetic control, and a no-template control allows for the evaluation of every reagent in these complex mixtures, every time a testing procedure is performed. In contrast, the standard genomic-only strategy evaluates approximately one half of the allele-specific reagents in every run (all wild-type allele-specific reagents, and a few mutant allele-specific reagents). Although all of these allele-specific test reagents are optimized to operate at one specific set of conditions, minor changes in these conditions or slight procedural modifications may induce a spectrum of changes that are not necessarily equivalent among all of the different test reagents. Temperature shifts decreasing the performance or specificity of one subset of allele-specific reagents may not influence another subset in the mix. Unless every primer and probe is monitored, we can only assume the assay is performing as expected for all of the reagents.

Through the use of genomic DNA controls and separate QC practices evaluating DNA isolation procedures, the only break in a complete and cost-effective QC testing methodology was the evaluation of the mutation-specific primers and probes. By using synthetic reference standards in conjunction with genomic DNA controls, we have developed a simple and efficient solution to fill this deficiency and to create a comprehensive QC methodology.

This methodology is highly valuable for CF testing and undoubtedly has application in several areas of molecular diagnostics. Multiplex testing and rare mutations have created the need for better ways to evaluate and monitor every component of these increasingly complex assays. Although genomic DNA controls are considered the gold standard for QC testing, it is essential that their limitations be recognized and supplemented with new methods or strategies to retain an uncompromised level of scrutiny necessary for molecular testing.

Footnotes

B.A.B. and T.M.C. are employees of and receive consulting fees from Sacred Heart Medical Center Spokane, WA.

References

- National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards Molecular Diagnostic Methods for Genetic Diseases. Wayne: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 2000 NCCLS document MM1-A. [Google Scholar]

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and American College of Medical Genetics: Preconception and prenatal carrier screening for cystic fibrosis, clinical and laboratory guidelines. Washington DC, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Clinical laboratory improvement amendments of 1988; Final rule. Fed Reg. 1992;57:7002–7003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Genetic Testing under CLIA. Fed Reg. 2000;65:25928–24934. [Google Scholar]

- Highsmith WE, Burch LH, Zhou Z, Olsen JC, Boat TE, Spock A, Gorvoy JD, Quittel L, Friedman KJ, Silverman LM, Boucher RC, Knowles MR. A novel mutation in the cystic fibrosis gene in patients with pulmonary disease but normal sweat chloride concentrations. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:974–980. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410133311503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerem B-S, Rommens JM, Buchanan JA, Markiewicz D, Cox TK, Chakravarti A, Buchwald M, Tsui L-C. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: genetic analysis. Science. 1989;245:1073–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.2570460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riordan JR, Rommens JM, Kerem B-S, Alon N, Rozmahel R, Grzelczak Z, Zielenski J, Lok S, Plavsic N, Chou JL, Drumm ML, Iannuzzi ML, Collins FS, Tsui L-C. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science. 1989;245:1066–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.2475911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rommens JM, Iannuzzi MC, Kerem B-S, Drumm ML, Melmer G, Dean M, Rozmahel R, Cole JL, Kennedy D, Hidaka N, Buchwald M, Roirdan J, Tsui L-C, Collins FS. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: chromosome walking and jumping. Science. 1989;245:1059–1065. doi: 10.1126/science.2772657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grody WW, Cutting GR, Klinger K, Richards CS, Watson MS, Desnick RJ. Laboratory standards and guidelines for population-based cystic fibrosis carrier screening. Genet Med. 2001;3:149–154. doi: 10.1097/00125817-200103000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson MS, Cutting GR, Desnick RJ, Driscoll DA, Klinger K, Mennuti M, Palomaki GE, Popovich BW, Pratt VM, Rohlfs EM, Strom CM, Richards CS, Witt DR, Grody WW. Cystic fibrosis population carrier screening: 2004 revision of the American College of Medical Genetics mutation panel. Genet Med. 2004;6:387–391. doi: 10.1097/01.GIM.0000139506.11694.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]