Abstract

Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) inhibits cytokine-induced endothelial cell activation through its antioxidative properties. However, the effect of PEDF on restenosis remains to be elucidated. Because the pathophysiological feature of restenosis is characterized by increased superoxide formation and accumulation of smooth muscle cells (SMCs), PEDF may inhibit this process via suppression of reactive oxygen species generation. We investigated here whether PEDF could prevent neointimal formation after balloon injury. PEDF levels were decreased in balloon-injured arteries. Adenoviral vector encoding human PEDF (Ad-PEDF) prevented neointimal formation. Expression and superoxide generation of the membrane components of NADPH oxidase, p22phox and gp91phox, in the neointima were also suppressed by Ad-PEDF. Ad-PEDF reduced G1 cyclin (cyclin D1 and E) expression and increased p27, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor. In vitro, PEDF inhibited platelet-derived growth factor-BB-induced SMC proliferation and migration by blocking reactive oxygen species generation through suppression of NADPH oxidase activity via down-regulation of p22PHOX and gp91PHOX. PEDF down-regulated G1 cyclins and up-regulated p27 levels in platelet-derived growth factor-BB-exposed SMCs as well. These results demonstrate that PEDF could inhibit neointimal formation via suppression of NADPH oxidase-mediated reactive oxygen species generation. Our present study suggests that substitution of PEDF may be a novel therapeutic strategy for restenosis after balloon angioplasty.

Atherosclerosis is manifested clinically as cardiovascular disease, which is a leading cause of mortality and morbidity in the Western world.1 Although percutaneous transluminal angioplasty is a well-established procedure for atherosclerotic arterial disease, restenosis after angioplasty remains a major limitation of this procedure.2 It is generally considered that enhanced proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs) via overexpression of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) is mainly involved in the process of excessive neointimal formation after balloon injury.3,4 Therefore, blockade of the PDGF-elicited SMC proliferation and migration would be a novel therapeutic target for restenosis after angioplasty.

Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) is a glycoprotein that belongs to the superfamily of serine protease inhibitors.5 It was first purified from the conditioned media of human retinal pigment epithelial cells as a factor with potent neuronal differentiating activity.5 Recently, PEDF has been shown to be a highly effective inhibitor of angiogenesis in cell culture and animal models. PEDF inhibits the growth and migration of cultured endothelial cells (ECs), and it potently suppresses ischemia-induced retinal neovascularization.6,7 In addition, we have recently found that PEDF blocks tumor necrosis factor-α- or angiotensin II-induced EC activation through its antioxidative properties.8,9 These observations suggest that PEDF could exert beneficial effects on atherosclerosis by suppressing the inflammatory proliferative responses to injuries. However, the protective role of PEDF against restenosis after angioplasty remains to be elucidated.

A growing body of evidence suggests the implication of oxidative stress in neointimal formation after angioplasty as well.10,11,12,13 Experimental studies show a protective effect of antioxidants on neointimal thickening or remodeling after balloon injury.12,13 These findings led us to speculate that PEDF could inhibit the SMC proliferation and migration after balloon injury by suppressing oxidative stress generation. In this study, we have investigated whether and how PEDF could block the neointimal hyperplasia in balloon-injured rat carotid arteries.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Anti-PEDF polyclonal antibody (Ab) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-cyclin D1 monoclonal antibody (mAb), anti-cyclin E polyclonal Ab, and anti-p27 polyclonal Ab were from BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ. Human recombinant PDGF-BB, NADPH, and N-acetylcysteine (NAC) were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). [3H]Thymidine was from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Buckinghamshire, UK).

Preparation of Recombinant Adenovirus

Adenoplasmid-expressing human PEDF was obtained from Invivogen, San Diego, CA. After transfection of the adenovirus plasmids into human embryonic kidney 293 cells, the adenovirus-expressing PEDF (Ad-PEDF) was purified on a cesium chloride gradient and then applied to Bio-Gel P-6DG gel (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and eluted with phosphate-buffered saline containing 2% sucrose and 2 mmol/L MgCl2. The titer of the virus stock was determined by a plaque-forming assay using 293 cells and expressed as plaque-forming units (PFU). Adenovirus-expressing bacterial β-galactosidase (Ad-LacZ) was used as a control adenovirus.

Rat Carotid Artery Balloon Injury Model

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (weighting 350 to 400 g at 9 to 10 weeks; Charles River Breeding Laboratories, Yokohama, Japan) were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg intraperitoneal). After a midcervical incision, the left common carotid artery and its bifurcation were exposed. To prevent acute thrombosis during procedure, heparin sodium (200 IU/kg) was intravenously injected before the balloon injury operation. Then, the left common carotid artery was balloon-injured three times with a 2F Fogarty catheter (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA) inserted through the external carotid artery as described previously.14 Sham-operated rats (SHAM) underwent the same operation, except that the balloon was not inserted. For adenovirus infection, two vascular clips were placed at the distal and proximal ends of the injured arterial segment. Then, the lumen of the injured segment between the two clips was incubated with 150 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (Con), Ad-PEDF, or Ad-LacZ (5 × 109 PFU/ml) for 20 minutes. On the indicated days after the procedure, the left common carotid arteries were excised for morphometric, immunohistochemical, and Western blot analyses. All animal experiments were conducted according to the guidelines provided by the Kurume University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee under an approved protocol.

Morphometric Analysis

After fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde, the specimens of carotid arteries were embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 3-μm intervals, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. To evaluate thickening of the neointima, the areas encroached by the external elastic lamina (EEL area), the internal elastic lamina (IEL area), and the lumen area were measured with a computerized digital image analysis system (NIH Image; Bethesda, MD). The neointima to media area (I/M) ratio was calculated as the following formula: I/M ratio (%) = [IEL area − lumen area]/[EEL area − IEL area] × 100 (%).

Immunohistochemical Analysis

After perfusion and fixation with 2.5% glutaraldehyde, the specimens of carotid arteries were embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 4-μm intervals, and mounted on glass slides. The sections were incubated in 0.3% hydrogen peroxide methanol for 30 minutes to block endogenous peroxidase activity and incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-PEDF polyclonal Ab, antiproliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) mouse mAb (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark), anti-α-smooth muscle actin mouse mAb (PROGEN Biotechnik GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany), anti-CD68 mouse mAb (Serotec Ltd., Oxford, UK), anti-p22PHOX rabbit polyclonal Ab (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or anti-gp91PHOX goat polyclonal Ab (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Then, the sections were incubated with biotinylated horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary (DAKO) for 60 minutes and visualized with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine solution (Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan).

Western Blot Analysis

Fifty micrograms of protein extracted from rat carotid arteries or cultured human SMCs were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blotting with a specific primary Ab against PEDF, p22PHOX, gp91PHOX, cyclin D1, cyclin E, p27, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and α-tubulin (Sigma) and a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary Ab (Promega, Madison, WI). Detection was performed by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Dihydroethidium (DHE) Staining

After excision, the specimens of carotid arteries were embedded in OCT compound (Tissue-Tek; Sakura Finetechnical Co, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) to freeze on dry ice and were cut into 10-μm sections. The frozen sections were incubated with 2 μmol/L DHE (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) at 37°C for 30 minutes in the dark. Images were obtained by confocal laser-scanning fluorescence microscopy. DHE staining of cultured SMCs was performed with the same procedure.

Purification of PEDF Protein

PEDF proteins were prepared and purified as described previously.15 Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis of purified PEDF proteins revealed a single band with a molecular mass of about 50 kd, which showed positive reactivity with mAb against human PEDF (Transgenic, Kumamoto, Japan).

Cells

Human aortic SMCs were cultured in SMC basal medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum, 0.5 ng/ml human epidermal growth factor, 5 μg/ml insulin, and 1 ng/ml human fibroblast growth factor-B according to the supplier’s instructions (CAMBREX, Walkersville, MD). PDGF-BB treatment was performed in SMC basal medium supplemented with 1% fetal bovine serum alone.

Primers and Probes

Primer sequences used in semiquantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction were 5′-CCACTTACTGCTGTCCGTGCC-3′ and 5′-CTGGGAGCAACACCTTGGAAAC-3′ for rat p22PHOX mRNA and 5′-TCACGCCCTTTGCCTCCATTC-3′ and 5′-CGTTATCCCAGTTGGGCCGTC-3′ for rat gp91PHOX mRNA. Sequences of the upstream and downstream primers used in semiquantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction for detecting rat β-actin mRNAs were the same as described previously.16

Semiquantitative Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction

Poly(A)+RNAs were isolated from SMCs as described previously.16 The amounts of poly(A)+RNA templates (30 ng) and cycle numbers (28 cycles for rat p22PHOX gp91PHOX genes and 22 cycles for β-actin gene) for amplification were chosen in quantitative ranges where reactions proceeded linearly. These were determined by plotting signal intensities as functions of the template amounts and cycle numbers.

NADPH Oxidase Assay

SMCs were treated with 20 ng/ml PDGF-BB in the presence or absence of 10 nmol/L PEDF for 4 hours, and then the NADPH oxidase activity of the cells was measured by the Diogenes assay (National Diagnostics, Inc., Atlanta, GA) containing luminol (as an electron acceptor) with 100 μmol/L NADPH (as a substrate) according to the supplier’s recommendation.

Intracellular Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Generation

SMCs were treated with 20 ng/ml PDGF-BB in the presence or absence of 10 nmol/L PEDF for 4 hours. The intracellular formation of ROS was detected by using the fluorescent probe CM-H2DCFDA (Molecular Probes) as described previously.17

Measurements of [3H]Thymidine Incorporation in SMCs

SMCs were treated with the indicated concentration of PDGF-BB in the presence or absence of 10 nmol/L PEDF or 1 mmol/L NAC for 24 hours, and then [3H]thymidine incorporation was determined as described previously.18

Migration Assay

Modified Boyden chamber assays were performed for 5 hours at 37°C with 48-well microchemotaxis chambers (Neuro Probe; Biomap, Milan, Italy) and polycarbonate filters (8-μm pores; Nucleopore Corp., Pleasanton, CA) coated with 50 μg/ml fibronectin and 0.1% gelatin as described previously.19 In brief, cells (10,000/well) were added to the upper chamber in the presence or absence of 10 nmol/L PEDF, and 20 ng/ml PDGF-BB was added to the lower chamber. After the incubation period, the filter was removed and nonmigrated SMCs on the upper side of the filter were scraped off with a rubber scraper. The filters were then fixed with methanol and stained with Giemsa solution. Migrated SMCs attached to the lower side of the filter were counted in three randomly selected microscopic fields in each chamber, and the counts of migrated cells were averaged.

Statistical Analysis

All values were presented as means ± SE unless otherwise indicated; one-way analysis of variance followed by the Scheffé F test was performed for statistical comparisons. In Figures 1D and 5, an unpaired t-test was performed for comparison between groups; P < 0.05 was considered significant.

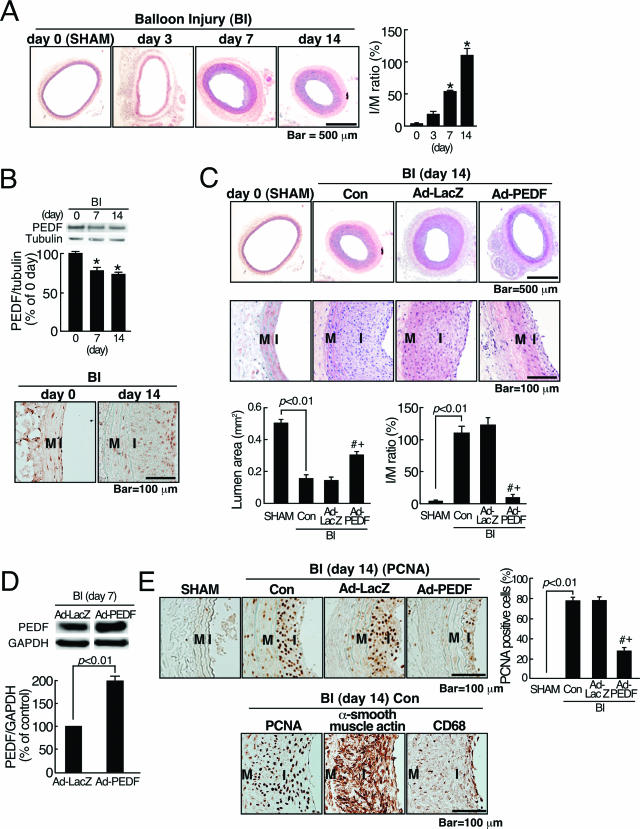

Figure 1.

Effects of Ad-PEDF on neointimal formation in balloon-injured arteries. A: A time course of neointimal hyperplasia after balloon injury (BI). Left panel shows representative microphotographs of neointimal hyperplasia after BI. Right panel shows the ratio of I/M in injured arteries. B: PEDF expression in rat carotid arteries. Top panels show representative results of Western blots and the quantitative data. Bottom panel shows representative microphotographs of PEDF immunostaining. C: Effects of Ad-PEDF on balloon-injured arteries. At 14 days after balloon injury, sham-operated (SHAM) and balloon-injured carotid arteries treated with phosphate-buffered saline (Con), Ad-LacZ, or Ad-PEDF were sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin and then examined by light microscopy. Top panels show representative microphotographs. Bottommost panel shows the lumen area and the ratio of I/M in the arteries. D: Western blot analysis of PEDF in injured arteries. Top panel shows representative results of Western blots. Bottom panel shows the quantitative data. E: Top panels show the immunohistochemical staining data of PCNA-positive cells (brown). Left panels show representative microphotographs. Right panel shows the ratio of PCNA-positive nuclei to total cells nuclei in the arteries. M; media, I; intima. Bottom panels show representative result of immunohistochemical staining for PCNA, α-smooth muscle actin, and CD68. N = 5–7 per group. A–E: Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. *P < 0.01 compared with the value at day 0. # and +P < 0.01 compared with the value with Con and Ad-LacZ, respectively.

Figure 5.

Effects of PEDF on cyclin D, cyclin E, and p27 expression in PDGF-BB-exposed SMCs. SMCs were treated with 20 ng/ml PDGF-BB in the presence or absence of 10 nmol/L PEDF for the indicated time periods. Western blot analysis was performed. Top panels show representative results of Western blots. Bottom panels show the quantitative data. N = 5–7 per group.

Results

PEDF Inhibits Neointimal Formation after Balloon Injury

We first examined the time course of neointimal formation after balloon injury. As shown in Figure 1A, histopathological examination of the injured arteries revealed a time-dependent increase in neointimal thickening; the I/M ratio at 14 days after balloon injury was increased to approximately sixfold compared with that of noninjured artery. We next studied where and how much PEDF was expressed in rat carotid arteries on day 0 and day 14 after balloon injury. As shown in Figure 1B, PEDF was normally expressed in intima, media, and adventitia of noninjured arteries. At day 14 after balloon injury, PEDF was predominantly expressed in the neointima, and its expression levels were decreased to about 70% of those in noninjured arteries. Therefore, to investigate the pathophysiological relevance of PEDF, we further examined the effects of PEDF overexpression on neointimal hyperplasia. For this, we prepared Ad-PEDF and Ad-LacZ and delivered 150 μl of each adenovirus (5 × 109 PFU/ml) to balloon-injured carotid arteries. Figure 1C, top two panels, shows representative microphotographs of rat carotid arteries 14 days after balloon injury. In the injured artery exposed to phosphate-buffered saline (Con) or Ad-LacZ, a significant concentric neointimal hyperplasia was observed, compared with sham operation (SHAM). Ad-PEDF significantly prevented the neointimal formation in injured arteries; the I/M ratio in Ad-PEDF infected arteries was decreased to about 1/5-fold of that in Ad-LacZ-infected or noninfected arteries (Figure 1C, bottom panels). We confirmed with Western blots that PEDF expression levels in the Ad-PEDF-treated arteries were increased to approximately twofold of those in Ad-LacZ-treated arteries (Figure 1D), thus suggesting that Ad-PEDF treatment restored the decrease in PEDF levels in balloon-injured arteries.

Furthermore, immunohistochemical detection of proliferating cells revealed that the ratio of PCNA-positive cell nuclei to total cell nuclei was significantly lower in Ad-PEDF-infected arteries than in Ad-LacZ-infected or noninfected injured arteries (Figure 1E, top panels). In addition, most of the neointimal and medial cells were positive for α-smooth muscle actin, and CD68-positive macrophages were sparsely observed in the lesions (Figure 1E, bottom panels).

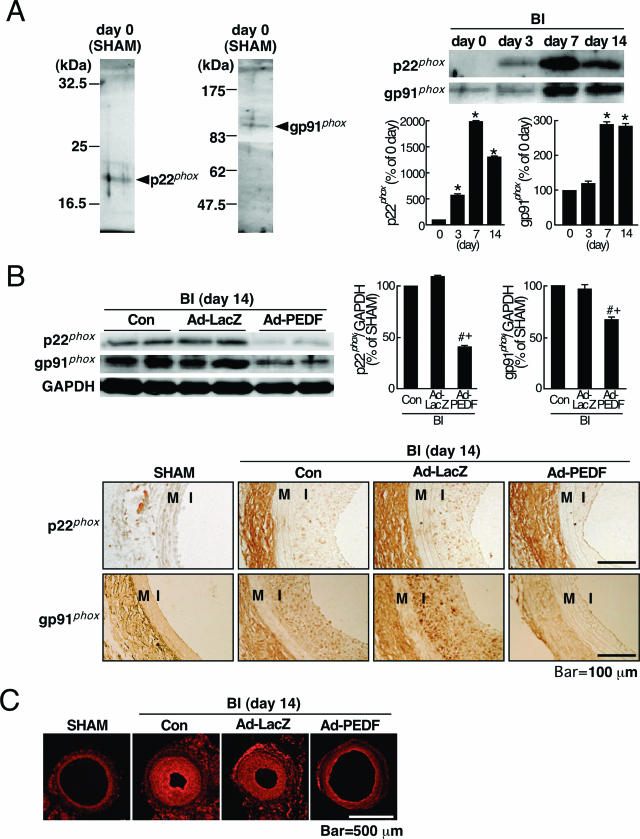

PEDF Inhibits Expression of NADPH Oxidase Components and Superoxide Generation in Injured Artery

Several articles have shown the active involvement of NADPH oxidase-mediated ROS generation in neointi-mal hyperplasia after balloon injury.10,11,12,13 Therefore, we next examined the effects of Ad-PEDF on expression levels of p22phox and gp91phox, key components of NADPH oxidase with respect to its enzymatic activity,20 and superoxide generation in injured arteries. For this, we first checked the specificity of anti-p22PHOX and anti-gp91PHOX Abs used here. As shown in Figure 2A, left panels, the Abs directed against p22PHOX and gp91PHOX showed single bands at 22 and 91 kd, respectively. When Western blotting was performed without the Abs as a negative control, no bands were detected (data not shown). These results supported the specificity of anti-p22PHOX and anti-gp91PHOX Abs used for Western blot analysis. Further, as shown in Figure 2A, right panels, the expression levels of p22phox and gp91phox began to increase at 3 days after balloon injury and reached a maximum at day 7; the peak values of p22phox and gp91phox were 20- and threefold higher than the basal levels, respectively. We also confirmed here that Ad-PEDF significantly decreased the expression levels of two membrane components of NADPH oxidase in injured arteries compared with phosphate-buffered saline (Con) or Ad-LacZ treatment (Figure 2B, top panels). Moreover, immunohistochemical analysis revealed that Ad-PEDF decreased expression levels of p22phox and gp91phox in the neointima, but not adventitia, compared with those of Con or Ad-LacZ (Figure 2B, bottom panels). Further, DHE staining, which is specific for superoxide generation,21 showed a high-intensity fluorescence signal in the neointima treated with Con or Ad-LacZ (Figure 2C). Ad-PEDF treatment attenuated the signal in injured artery (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Effects of Ad-PEDF on NADPH oxidase expression and superoxide generation in balloon-injured arteries. A: Left panels show representative results of Western blots of p22phox and gp91phox. Right top panels show representative results of Western blots showing serial change in expression of p22phox and gp91phox after balloon injury (BI). Right bottom panels show the quantitative data. B and C: Effects of Ad-PEDF on p22phox and gp91phox expression and superoxide generation in balloon-injured arteries. At 14 days after balloon injury, balloon-injured carotid arteries treated with phosphate-buffered saline (Con), Ad-LacZ, or Ad-PEDF were analyzed for immunohistochemistry, Western blots, and DHE staining. B: The representative results of Western blots are shown (top left panels). Top right panels show the quantitative data. Bottom panels show representative immunohistochemical staining of p22phox- and gp91phox-positive cells (brown). M; media, I; intima. C: In situ detection of superoxide generation with DHE staining (red). N = 5–7 per group. A–C: Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. *P < 0.01 compared with the value at day 0. # and +P < 0.01 compared with the value with Con and Ad-LacZ, respectively.

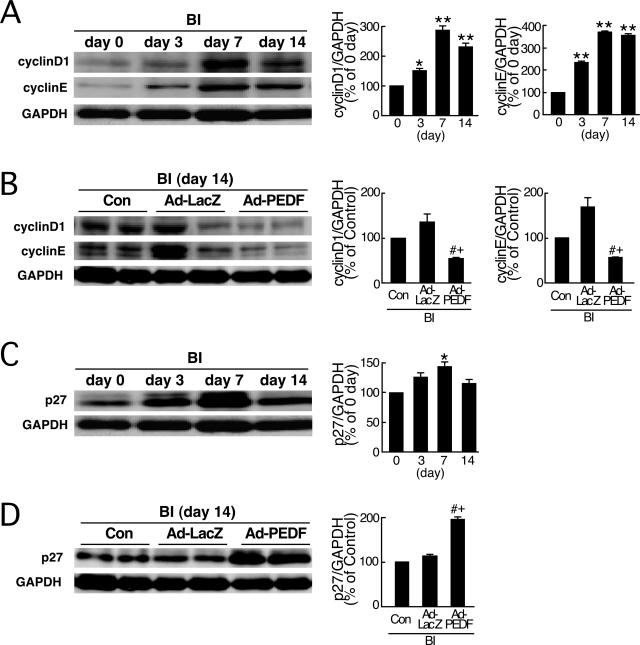

PEDF Inhibits Cyclin D1 and E Expression and Increases p27 Levels in Injured Artery

The entry of vascular cells into the cell cycle plays an important role in the pathogenesis of postangioplasty restenosis.22,23,24 Therefore, we next examined the effects of Ad-PEDF on G1 cyclins (cyclins D1 and E) and p27, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor that causes G1 arrest in injured arteries.25 As shown Figure 3A, cyclins D1 and E, whose expression levels were low in uninjured arteries, were induced in response to injury and reached a peak 7 days after injury. Ad-PEDF re-duced the levels of these cyclins compared with Con or Ad-LacZ (Figure 3B). As shown in Figure 3C, p27 was found to be moderately expressed in uninjured arteries, and the levels were up-regulated after balloon injury. Ad-PEDF further enhanced the expression levels of p27 compared with Con or Ad-LacZ (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Effects of Ad-PEDF on cyclin D1, cyclin E, and p27 expression in balloon-injured arteries. A and C: Western blots showing serial change in expression of cyclins D1 and E (A) and p27 (C) after balloon injury (BI). B and D: Effects of Ad-PEDF on cyclins D1 and E (B) and p27 (D) in balloon-injured arteries. At 14 days after balloon injury, sham-operated [day 0 (SHAM)] and balloon-injured carotid arteries treated with phosphate-buffered saline (Con), Ad-LacZ, or Ad-PEDF were analyzed for Western blots. A–D: Each left panel shows representative results of Western blots. Each right panel shows the quantitative data. N = 5–7 per group. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. * and **P < 0.05 and P < 0.01 compared with the value at day 0. # and +P < 0.01 compared with the value with Con and Ad-LacZ, respectively.

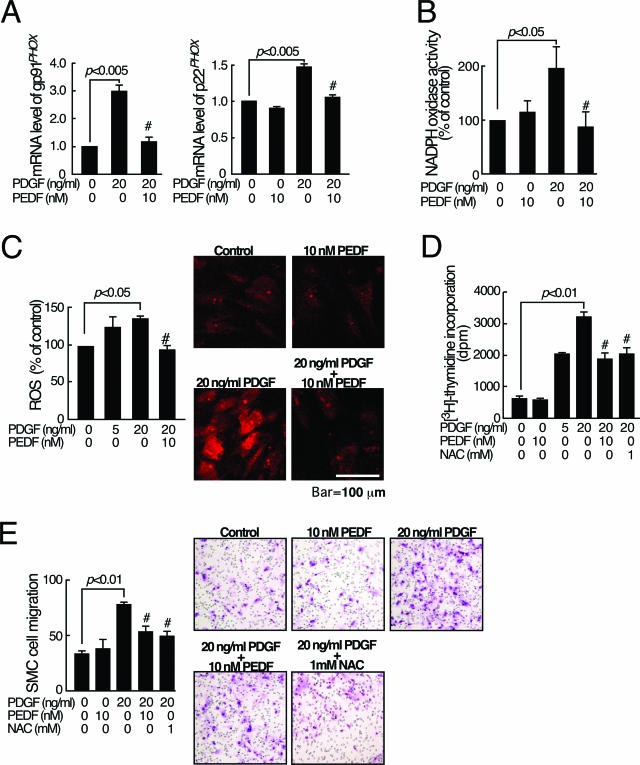

PEDF Inhibits NADPH Oxidase-Mediated ROS Generation in PDGF-BB-Exposed SMCs

Above-mentioned in vivo data suggest that some part of the beneficial actions of PEDF is due to its antioxidative effects via the suppression of p22phox and gp91phox protein expression in the neointima. Because PDGF is a potent mitogen and migratory factor of SMC via intracellular ROS generation, thus being considered to play an important role in the pathogenesis of intimal hyperplasia after balloon injury,3,4,26 we conducted the in vitro SMC experiments using PDGF-BB as a stimulant to confirm whether SMC is the target for the antioxidative actions of PEDF. In the in vitro experiments, we chose the concentration of PEDF at 10 nmol/L because we have recently found that PEDF at 10 nmol/L blocks tumor necrosis factor-α- or angiotensin II-induced EC activation in vitro.8,9 Under these conditions, we first investigated whether PEDF could inhibit the PDGF-BB signaling in cultured SMCs by suppressing NADPH oxidase-mediated ROS generation. As shown in Figure 4, A and B, 10 nmol/L PEDF completely inhibited the PDGF-BB-induced up-regulation of p22PHOX and gp91PHOX mRNA levels and subsequent increase in NADPH oxidase activity in SMCs. Furthermore, 10 nmol/L PEDF completely inhibited the PDGF-BB-induced ROS generation in SMCs (Figure 4C, left panel). Figure 4C, right panel, shows a representative microphotograph of DHE staining of SMCs treated with or without PDGF-BB or PEDF. These observations suggest that PDGF-BB elicits ROS generation in SMCs via NADPH oxidase activity, which was completely blocked by PEDF.

Figure 4.

Effects of PEDF on NADPH oxidase expression, ROS generation, proliferation, and migration in PDGF-BB-exposed SMCs. SMCs were treated with the indicated concentration of PDGF-BB in the presence or absence of 10 nmol/L PEDF. A: After 4 hours, semiquantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction was performed. Data were normalized by the intensity of β-actin mRNA-derived signals and related to the value of the control. B: NADPH oxidase activity was measured. C: ROS generation was measured. Right panel shows the representative microphotographs of DHE staining of the cells. D: After 24 hours, DNA synthesis was measured. E: After 5 hours, migrated cells were counted. Right panel shows the representative microphotographs of migrated cells. N = 5–7 per group. A–E: Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. #P < 0.01 compared with the value with 20 ng/ml PDGF-BB alone.

PEDF Inhibits PDGF-BB-Induced Proliferation and Migration of Cultured SMCs

We next examined whether PEDF could inhibit the PDGF-BB-induced proliferation and migration of SMCs. As shown in Figure 4D, PDGF-BB dose-dependently increased DNA synthesis in SMCs, which was significantly blocked by PEDF. Furthermore, PEDF was found to inhibit the PDGF-BB-induced migration of cultured SMCs (Figure 4E). An antioxidant, NAC, completely blocked the PDGF-BB-induced proliferation and migration of SMCs (Figure 4, D and E).

PEDF Inhibits Cyclins D1 and E Expression and Increases p27 Levels in PDGF-BB-Exposed SMCs

We further studied the effects of PEDF on cyclin D1, cyclin E, and p27 expression in PDGF-BB-exposed SMCs. As shown in Figure 5, PEDF down-regulated expression levels of cyclins D1 and E in PDGF-BB-exposed SMCs. Furthermore, PEDF was found to enhance the expression levels of p27 in PDGF-BB-exposed SMCs.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated for the first time that PEDF could inhibit the intimal hyperplasia by down-regulating G1 cyclin expression and up-regulating a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, p27 levels, via suppression of NADPH oxidase-mediated ROS generation. We also found here that PEDF inhibited the PDGF-BB signaling to proliferation and migration of SMCs through its antioxidative properties. These observations suggest that suppression of p22phox and gp91phox expression in SMCs would be a central mechanism by which PEDF inhibited the neointimal formation in balloon-injured arteries. Our present study provides a novel therapeutic potential of PEDF for restenosis after balloon angioplasty.

We first examined the kinetics of neointimal formation in rat carotid artery injury. In this study, the I/M ratio was time-dependently increased and reached a maximum at 14 days after balloon injury (Figure 1A), which was consistent with the previous reports.11,27 Further, PEDF was normally expressed in the intima, media, and adventitia of rat carotid arteries. At day 14 after balloon injury, PEDF was predominantly expressed in the intima, and its expression levels were down-regulated (Figure 1B). In this study, we did not perform double staining of the sections with Abs directed against α-smooth muscle actin or CD68. Therefore, we did not clarify exactly which types of cells expressed PEDF. However, since most of the neointimal cells were positive for α-smooth muscle actin at day 14 after balloon injury (Figure 1E), our present observations suggest that the main expression sites of PEDF may be shifted to SMCs in the neointima after balloon injury. In this study, to clarify the pathophysiological role of PEDF, we evaluated the effects of Ad-PEDF on neointimal hyperplasia at 14 days after balloon injury. We found here that Ad-PEDF actually increased PEDF levels in the injured arteries and subsequently suppressed the neointimal formation (Figure 1C). In addition, Ad-PEDF significantly decreased the ratio of PCNA-positive cells to total cells in balloon-injured arteries (Figure 1E, top panels). These observations support the clinical relevance of PEDF overexpression in balloon-injured arteries. The present data were consistent with the previous finding that most of the proliferating cells in the neointima on day 14 after balloon injury were SMCs.28 Moreover, Szöcs et al11 have previously reported that macrophages are not detected in the media or neointima on days 3 and 15 after balloon injury and that superoxide is localized to regions of the vessel wall containing α-smooth muscle actin-positive cells. Therefore, although we cannot completely exclude the potential role of macrophage infiltration at early stage in neointimal formation, our present results and above-mentioned previous findings suggest that the increased proliferative activity of SMCs in the neointimal lesions could be one of the primary targets of Ad-PEDF in our model.

In the present study, the effects of Ad-PEDF on the ratio of PCNA-positive cells to total cells were modest (Figure 1E, top panels), whereas those of PEDF on neointimal formation were drastic. The findings suggest that PEDF could inhibit the neointimal formation, at least in part, by mechanisms other than growth inhibition. In vitro experiments (Figure 4E) suggest the possibility that PEDF could inhibit the neointimal formation by suppressing the migration of SMCs in balloon-injured arteries. Further, although we do not have data to show the proapoptotic properties of PEDF on SMCs, PEDF may promote apoptotic cell death of proliferating SMCs and subsequently protect against restenosis after balloon injury. The findings that PEDF up-regulates Fas ligand in ECs, thereby specifically sensitizing Fas-positive proliferating ECs to apoptosis support our speculation.29 Taken together, the sum effects of Ad-PEDF on proliferation, migration, and apoptosis of SMCs could regulate the I/M ratio. Therefore, the extent of suppression of I/M ratio by Ad-PEDF may not be necessarily in proportion to the degree of increased amounts of PEDF.

Several articles have suggested that NADPH oxidase intrinsic to the vessel wall contributes to the increased ROS production in balloon-injured arteries.10,11,12,13 In addition, animal studies with antioxidants have provided a causal role for ROS generation in neointimal hyperplasia after balloon injury12,13 Therefore, our present findings suggest that PEDF could inhibit the neointimal hyperplasia after balloon injury by blocking the NADPH oxidase-mediated ROS generation in SMCs. A chimeric peptide inhibitor that interferes with the assembly of vascular NADPH oxidase components was reported to suppress angioplasty-induced superoxide generation and neointimal hyperplasia of carotid artery in male Sprague-Dawley rats.13 Further, as shown in Figure 4, D and E, an antioxidant NAC exerted similar effects on cultured SMCs as did PEDF; NAC significantly inhibited the PDGF-BB-induced increase in DNA synthesis and migration of SMCs. These observations further support the concept that NADPH oxidase-derived ROS generation could play a role in neointimal formation in our model, which was a molecular target of PEDF.

ROS have been known to modulate expression of G1 cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, p27.30,31,32 Because the entry of SMCs into the cell cycle plays a central role in the pathogenesis of angioplasty restenosis,22,23,24 PEDF may inhibit the intimal hyperplasia by modulating the cell cycle regulatory proteins through its antioxidative properties. Taken together, down-regulation of G1 cyclins and up-regulation of p27 could be a crucial downstream target for PEDF. The findings that G1 cyclins are overexpressed in injured arteries and that overexpression of p27 results in significant inhibition of intimal hyperplasia after balloon injury support our speculation.24,33,34

To elucidate further the molecular mechanism underlying the antiatherosclerotic effects of PEDF on balloon-injured arteries, we conducted in vitro experiments. We chose here PDGF-BB as a stimulant because PDGF-BB was highly expressed at the site of balloon injury (data not shown), and there is a growing body of evidence that PDGF-BB is a potent mitogen and migratory factor for SMCs, thus being involved in the pathogenesis of intimal hyperplasia after balloon injury.3,4 We have shown in the present study that PEDF proteins also have atheroprotective properties in vitro; PEDF inhibited the NADPH oxidase-mediated ROS generation in PDGF-BB-exposed SMCs, a key downstream molecule of PDGF-BB signaling to SMC proliferation and migration26 (Figure 4). Furthermore, PEDF was found not only to inhibit up-regulation of cyclins D1 and E but also to enhance the expression of p27 in PDGF-BB-exposed SMCs (Figure 5). These observations further support the concept that PEDF could inhibit the restenosis after angioplasty by suppressing the PDGF-induced, NADPH oxidase-mediated ROS generation in SMCs. Further studies are needed to address the issue of whether PEDF could suppress other growth factor or chemokine signaling in SMCs via antioxidative properties, which may also contribute to the inhibition of restenosis after angioplasty.

Our present study has extended the previous findings showing that PEDF has vasoprotective properties in vitro by inhibiting EC activation.8,9 Thus, the present observations provide a novel beneficial aspect of PEDF on atherosclerosis; PEDF could prevent SMC proliferation and migration, the characteristic changes of restenosis after angioplasty, by suppressing the NADPH oxidase-elicited ROS generation, thereby inhibiting the progression of vascular remodeling in atherosclerosis. Therefore, although the degree of reduction of PEDF on vascular injury was not so large (PEDF level was reduced by 30%), our present study suggests that substitution of PEDF may offer a promising strategy for halting the development and progression of restenosis after angioplasty.

Limitations

First, since the regulation of p22phox and gp91phox gene expression in SMCs is largely unknown, we did not clarify here how PEDF suppressed p22phox and gp91phox expression in the neointima. Second, in the present study, Ad-PEDF nearly completely prevented the neointimal formation, although it partially reduced the levels of p22phox and gp91phox in balloon-injured arteries (Figure 2B). Other mechanisms such as inhibition of the assembly of NADPH oxidase complex may be involved in the suppressive effects of PEDF on NADPH oxidase activation. Therefore, it is interesting to examine whether protein kinase C inhibitors, which are known to suppress the assembly of NADPH oxidase complex in SMCs, augment the inhibitory effects of PEDF on neointimal formation.35 Molecular mechanisms by which PEDF inhibited the neointimal formation after balloon injury should be further examined. Third, in this study, we cannot completely exclude the possibility that PEDF inhibited the neointimal formation by suppressing macrophage infiltration at an early stage. Fourth, in the present study, the degree of reduction of PEDF on vascular injury was not so large, and Ad-PEDF treatment increased PEDF levels to about twofold of those in Ad-LacZ-treated injured arteries. Therefore, further study is needed to clarify whether overexpression of excess amounts of PEDF may have clinical relevance in the prevention of restenosis after angioplasty in humans.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Sho-ichi Yamagishi, Department of Medicine, Division of Cardio-Vascular Medicine, Kurume University School of Medicine, 67 Asahi-machi, Kurume 830-0011, Japan. E-mail: shoichi@med.kurume-u.ac.jp.

Supported in part by grants of Venture Research and Development Centers from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan to S.Y.

References

- Lusis AJ. Atherosclerosis. Nature. 2000;407:233–241. doi: 10.1038/35025203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett MR, O’Sullivan M. Mechanisms of angioplasty and stent restenosis: implications for design of rational therapy. Pharmacol Ther. 2001;91:149–166. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(01)00153-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitzki A. PDGF receptor kinase inhibitors for the treatment of restenosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;65:581–586. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casterella PJ, Teirstein PS. Prevention of coronary restenosis. Cardiol Rev. 1999;7:219–231. doi: 10.1097/00045415-199907000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tombran-Tink J, Chader CG, Johnson LV. PEDF: pigment epithelium-derived factor with potent neuronal differentiative activity. Exp Eye Res. 1991;53:411–414. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(91)90248-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DW, Volpert OV, Gillis P, Crawford SE, Xu HJ, Benedict W, Bouck NP. Pigment epithelium-derived factor: a potent inhibitor of angiogenesis. Science. 1999;285:245–248. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5425.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duh EJ, Yang HS, Suzuma I, Miyagi M, Youngman E, Mori K, Katai M, Yan L, Suzuma K, West K, Davarya S, Tong P, Gehlbach P, Pearlman J, Crabb JW, Aiello LP, Campochiaro PA, Zack DJ. Pigment epithelium-derived factor suppresses ischemia-induced retinal neovascularization and VEGF-induced migration and growth. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:821–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi S, Inagaki Y, Nakamura K, Abe R, Shimizu T, Yoshimura A, Imaizumi T. Pigment epithelium-derived factor inhibits TNF-alpha-induced interleukin-6 expression in endothelial cells by suppressing NADPH oxidase-mediated reactive oxygen species generation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;37:497–506. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi S, Nakamura K, Ueda S, Kato S, Imaizumi T. Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) blocks angiotensin II signaling in endothelial cells via suppression of NADPH oxidase: a novel anti-oxidative mechanism of PEDF. Cell Tissue Res. 2005;320:437–445. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-1094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Niculescu R, Wang D, Patel S, Davenpeck KL, Zalewski A. Increased NAD(P)H oxidase and reactive oxygen species in coronary arteries after balloon injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:739–745. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.5.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szöcs K, Lassegue B, Sorescu D, Hilenski LL, Valppu L, Couse TL, Wilcox JN, Quinn MT, Lambeth JD, Griendling KK. Upregulation of Nox-based NAD(P)H oxidases in restenosis after carotid injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:21–27. doi: 10.1161/hq0102.102189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza HP, Souza LC, Anastacio VM, Pereira AC, Junqueira ML, Krieger JE, da Luz PL, Augusto O, Laurindo FR. Vascular oxidant stress early after balloon injury: evidence for increased NAD(P)H oxidoreductase activity. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;28:1232–1242. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson GM, Dourron HM, Liu J, Carretero OA, Reddy DJ, Andrzejewski T, Pagano PJ. Novel NAD(P)H oxidase inhibitor suppresses angioplasty-induced superoxide and neointimal hyperplasia of rat carotid artery. Circ Res. 2003;92:637–643. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000063423.94645.8A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasukawa H, Imaizumi T, Matsuoka H, Nakashima A, Morimatsu M. Inhibition of intimal hyperplasia after balloon injury by antibodies to intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1. Circulation. 1997;95:1515–1522. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.6.1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi S, Inagaki Y, Amano S, Okamoto T, Takeuchi M, Makita Z. Pigment epithelium-derived factor protects cultured retinal pericytes from advanced glycation end products-induced injury through its antioxidative properties. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;296:877–882. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)00940-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi S, Inagaki Y, Okamoto T, Amano S, Koga K, Takeuchi M, Makita Z. Advanced glycation end products-induced apoptosis and overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in human cultured mesangial cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:20309–20315. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202634200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi SI, Edelstein D, Du XL, Kaneda Y, Guzman M, Brownlee M. Leptin induces mitochondrial superoxide production and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression in aortic endothelial cells by increasing fatty acid oxidation via protein kinase A. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:25096–25100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007383200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi S, Yamamoto Y, Harada S, Hsu CC, Yamamoto H. Advanced glycosylation end products stimulate the growth but inhibit the prostacyclin-producing ability of endothelial cells through interactions with their receptors. FEBS Lett. 1996;384:103–106. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00279-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi S, Yonekura H, Yamamoto Y, Fujimori H, Sakurai S, Tanaka N, Yamamoto H. Vascular endothelial growth factor acts as a pericyte mitogen under hypoxic conditions. Lab Invest. 1999;79:501–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griendling KK, Sorescu D, Ushio-Fukai M. NAD(P)H oxidase: role in cardiovascular biology and disease. Circ Res. 2000;86:494–501. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.5.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi S, Abe R, Inagaki Y, Nakamura K, Sugawara H, Inokuma D, Nakamura H, Shimizu T, Takeuchi M, Yoshimura A, Bucala R, Shimizu H, Imaizumi T. Minodronate, a newly developed nitrogen-containing bisphosphonate, suppresses melanoma growth and improves survival in nude mice by blocking vascular endothelial growth factor signaling. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1865–1874. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63239-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross R. Cell biology of atherosclerosis. Annu Rev Physiol. 1995;57:791–804. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.004043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby P, Tanaka H. The pathogenesis of coronary arteriosclerosis (“chronic rejection”) in transplanted hearts. Clin Transplant. 1994;8:313–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei GL, Krasinski K, Kearney M, Isner JM, Walsh K, Andres V. Temporally and spatially coordinated expression of cell cycle regulatory factors after angioplasty. Circ Res. 1997;80:418–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park KW, Kim DH, You HJ, Sir JJ, Jeon SI, Youn SW, Yang HM, Skurk C, Park YB, Walsh K, Kim HS. Activated forkhead transcription factor inhibits neointimal hyperplasia after angioplasty through induction of p27. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:742–747. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000156288.70849.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundaresan M, Yu ZX, Ferrans VJ, Irani K, Finkel T. Requirement for generation of H2O2 for platelet-derived growth factor signal transduction. Science. 1995;270:296–299. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5234.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata R, Kai H, Seki Y, Kato S, Morimatsu M, Kaibuchi K, Imaizumi T. Role of Rho-associated kinase in neointima formation after vascular injury. Circulation. 2001;103:284–289. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.2.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SJ, Kim HS, Yang HM, Park KW, Youn SW, Jeon SI, Kim DH, Koo BK, Chae IH, Choi DJ, Oh BH, Lee MM, Park YB. Thalidomide as a potent inhibitor of neointimal hyperplasia after balloon injury in rat carotid artery. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:885–891. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000124924.21961.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpert OV, Zaichuk T, Zhou W, Reiher F, Ferguson TA, Stuart PM, Amin M, Bouck NP. Inducer-stimulated Fas targets activated endothelium for destruction by anti-angiogenic thrombospondin-1 and pigment epithelium-derived factor. Nat Med. 2002;8:349–357. doi: 10.1038/nm0402-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekharam M, Trotti A, Cunnick JM, Wu J. Suppression of fibroblast cell cycle progression in G1 phase by N-acetylcysteine. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1998;149:210–216. doi: 10.1006/taap.1997.8361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SJ, Shyue SK, Shih MC, Chu TH, Chen YH, Ku HH, Chen JW, Tam KB, Chen YL. Superoxide dismutase and catalase inhibit oxidized low-density lipoprotein-induced human aortic smooth muscle cell proliferation: role of cell-cycle regulation, mitogen-activated protein kinases, and transcription factors. Atherosclerosis. 2007;190:124–134. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Wang X, Zeng L, Cai DY, Sabapathy K, Goff SP, Firpo EJ, Li B. ERK phosphorylates p66shcA on Ser36 and subsequently regulates p27kip1 expression via the Akt-FOXO3a pathway: implication of p27kip1 in cell response to oxidative stress. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:3705–3718. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-04-0301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun-Dullaeus RC, Mann MJ, Seay U, Zhang L, von Der Leyen HE, Morris RE, Dzau VJ. Cell cycle protein expression in vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro and in vivo is regulated through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and mammalian target of rapamycin. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:1152–1158. doi: 10.1161/hq0701.092104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner FC, Boehm M, Akyurek LM, San H, Yang ZY, Tashiro J, Nabel GJ, Nabel EG. Differential effects of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p27(Kip1), p21(Cip1), and p16(Ink4) on vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Circulation. 2000;101:2022–2025. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.17.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoguchi T, Li P, Umeda F, Yu HY, Kamimoto M, Imamura M, Aoki T, Etoh T, Hashimoto T, Naruse M, Sano H, Utsumi H, Nawata H. High glucose level and free fatty acid stimulate reactive oxygen species production through protein kinase C-dependent activation of NAD(P)H oxidase in cultured vascular cells. Diabetes. 2000;49:1939–1945. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.11.1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]