Abstract

Aging is accompanied by increased oxidative stress (OS) and accumulation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs). AGE formation in food is temperature-regulated, and ingestion of nutrients prepared with excess heat promotes AGE formation, OS, and cardiovascular disease in mice. We hypothesized that sustained exposure to the high levels of pro-oxidant AGEs in normal diets (RegAGE) contributes to aging via an increased AGE load, which causes AGER1 dysregulation and depletion of anti-oxidant capacity, and that an isocaloric, but AGE-restricted (by 50%) diet (LowAGE), would decrease these abnormalities. C57BL6 male mice with a life-long exposure to a LowAGE diet had higher than baseline levels of tissue AGER1 and glutathione/oxidized glutathione and reduced plasma 8-isoprostanes and tissue RAGE and p66shc levels compared with mice pair-fed the regular (RegAGE) diet. This was associated with a reduction in systemic AGE accumulation and amelioration of insulin resistance, albuminuria, and glomerulosclerosis. Moreover, lifespan was extended in LowAGE mice, compared with RegAGE mice. Thus, OS-dependent metabolic and end organ dysfunction of aging may result from life-long exposure to high levels of glycoxidants that exceed AGER1 and anti-oxidant reserve capacity. A reduced AGE diet preserved these innate defenses, resulting in decreased tissue damage and a longer lifespan in mice.

Environmental and genetic factors including elevated oxidant stress (OS), cumulative DNA damage, altered gene expression, telomere shortening, and energy utilization are among the postulated mechanisms of senescence and aging in organisms from yeast to mammals.1,2,3,4,5 The effects of increased OS are thought to be partly mediated by oxidative changes in proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, which alter their function.6 Excess OS can be diminished by manipulating genetic or environmental factors. Genetic models of increased longevity include loss-of-function mutations of the GH/IGF-1 axis and downstream signaling,7,8,9,10 as well as p66Shc,11 the FOXO transcription factors,12 catalase,13 and anti-oxidant mimetics.14 The most widely studied environmental intervention that prevents excess OS and extends lifespan is caloric restriction, which mimics many of the changes observed in the genetic models.1,5

Oxidants in vivo are multiple, heterogeneous, and include nonenzymatic reaction derivatives of free amine-containing nucleic acids, peptides, or lipids with ambient reducing sugars, termed advanced glycation/lipoxidation products (AGE/ALE or glycotoxins).15,16 Protein and lipid-derived AGE include Nε-carboxy-methyl-lysine (CML), Nε-carboxyethyl-lysine, methyl-glyoxal-hydroimidazolone, their precursors, and/or derivatives. These are products of normal metabolism in organisms ranging from single cells to mammals and are turned over or neutralized by receptors that promote AGE uptake and degradation, such as AGER1,17 and are excreted by the kidney.18 Thus, AGER1 functions to decrease OS. On the other hand, other AGE receptors promote OS after binding, the prime example being RAGE.19,20,21 AGE receptors can be up-regulated in vitro22; however, when AGEs are chronically elevated, ie, in diabetes, AGER1 can be down-regulated,23 but OS-promoting receptors, such as RAGE, are enhanced. RAGE promotes the formation of reactive oxygen species, inflammation, stress-responses, and apoptotic events.19,20,21 Excess AGEs are present in several diseases common in aging, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and chronic kidney disease (CKD).15,16,18,19,20,21,24,25,26

Nutrients that are thermally prepared for consumption are a rich source of protein- or fat-derived oxidation derivatives, including AGEs, and a host of toxic compounds in foods, some of which have been implicated in oncogenesis.27,28,29,30,31,32 Laboratory rodent food is high in protein, low in fat, supplemented with micronutrients, and routinely heated to ensure safety. The temperatures currently used are sufficiently high to inadvertently cause standard mouse chow to be rich in oxidant AGEs, not unlike levels present in the usual Western diet.27,30

Lowering the intake of dietary AGEs or glycotoxins, by restricting the temperature used in nutrient preparation, reduces circulating and tissue levels of AGEs.33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40 This was associated with a decrease in OS and inflammatory responses in patients with diabetes37 and CKD,40 and in animals a LowAGE diet prevents the development of insulin resistance and diabetes,41,42 cardiovascular disease,38 and CKD.43

Because it was not known whether a decreased intake of AGEs affects normal aging or lifespan in normal animals, we compared the effects of dietary AGE intake on age-related changes such as OS, glucose/insulin metabolism, kidney disease, and lifespan in mice pair-fed a regular diet or an isocaloric diet exposed to lower temperature (LowAGE diet). We found that the LowAGE diet contained lower oxidant AGEs and preserved anti-oxidant reserves, prevented kidney disease, and extended lifespan. These events could be attributable to suppressed OS-regulatory mechanisms and may be related to preservation of the capacity of AGER1 to respond to the increased AGE load that characterizes normal aging.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Diets

C57BL/6 mice (n = 84, male, 4 months of age) from the NIA caloric restriction colonies were individually caged and provided free access to water. Mice were assigned to two dietary groups (Table 1): a regular NIH-31 open formula (Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI) ad lib (RegAGE), and a rodent chow diet (LabDiet 5053; LabDiet, Purina Mills, Richmond, IN), equal in calories, nutrient, and micronutrient content to RegAGE, but, by limiting exposure to the standard temperature during manufacture, contained less measurable CML-like AGEs (LowAGE diet, ∼50% of RegAGE diet).38,42,43 Thus, compared with RegAGE, which is first steam-conditioned and pelleted at 70 to 75°C, for 1 to 2 minutes, and then dried at 55°C for 30 minutes, LowAGE was only exposed to 80°C for 1 minute, during pelleting. Micronutrient content was in excess of established requirements.38,42,43 Diets were purchased in small amounts (<5 kg) and kept at 4°C. Food consumption was monitored daily, for the first 4 weeks, by weighing the food of each individual mouse to assess exact intake, and weekly thereafter. After establishing the daily intake of RegAGE mice, the identical amount was given to both LowAGE and RegAGE mice. Throughout the study, food was completely consumed between feedings. Half of these mice (n = 20/dietary group) were used for procedures, ie, blood collection and glucose tolerance testing or sacrifice and tissue retrieval, and the remaining (n = 22/diet group) were used for analysis of survival curves.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Mouse

| Regular | Low | |

|---|---|---|

| Protein (g) | 20.0 | 20.0 |

| Fat | 4.5 | 4.5 |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 54.8 | 54.8 |

| Total calories (kcal/g) | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| AGE | 6.0 × 104 | 3.0 × 104 |

| Food/day/mouse (g) | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| AGE intake/day (U) | 30.0 × 10 | 15.5 × 104 |

| Total calories/day (kcal) | 20.0 | 20.1 |

Body weight was monitored two times per week during the first 3 months and then monthly because none of the groups showed sudden weight loss. At intervals, blood was collected from the tail vein of nonanesthetized mice (n = 5/group) and serum was separated and frozen for subsequent analyses. At sacrifice, tissue segments were placed in 2% freshly prepared paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline or were snap-frozen at −80°C.

All mice were maintained in a specific pathogen-free environment, with the room temperature maintained at 72°F, 50% humidity, and 12:12 light/dark cycles, at the Center for Laboratory Animal Science, Mount Sinai School of Medicine. Sentinel mice in the same room were examined every 3 months and tested sero-negative for pneumonia virus of mice, mouse hepatitis virus, mouse minute virus, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, mouse adenovirus, and Sendai virus and tested negative for parasites (eg, pinworm) and other routine pathogens. All experimental procedures complied with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, publication no. NIH 78-23, 1996).

AGE Measurements

Because CML-like AGEs, present in both the normal mouse chow as well as the tissues of animals and humans, and correlate with other AGEs and oxidants, ie, methyl glyoxal or lipid oxidation derivatives such as 8-isoprostanes, it is used as a surrogate marker of other AGEs.31 AGE concentrations in mouse sera, tissues, urine, and diets were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, using monoclonal antibodies reacting with CML-like (4G9; Alteon, Northvale, NJ) or methyl-glyoxal-like epitopes.31,37,40,41,42 Based on HPLC/GC-MS, the CML-bovine serum albumin standard contained 23 modified lys/mol, whereas the methyl-glyoxal-bovine serum albumin standard contained 23 modified arginine/mol.31 CML immunoreactivity (based on 4G9 monoclonal antibody) correlates with that of methyl-glyoxal-derivatives (based on 3D11 monoclonal antibody).31

Metabolic Studies

At 4 and 24 months, an intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (5% dextrose solution; 2 mg/g body weight) was performed in subgroups from each dietary group (n = 5), after an overnight fast.41,42 Blood samples were taken before and at intervals between 5 and 120 minutes after glucose infusion. Blood glucose was determined with an Elite glucometer (Bayer, Mishawaka, IN). Serum insulin levels were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Ultra-Sensitive mouse insulin kit; Alpco Diagnostics, Windham, NH).

Urinary Albumin Excretion Rate

Renal function was evaluated at 4 and 24 months by determining the urinary albumin/creatinine ratio in 24-hour urine samples collected from each group (n = 5). Urinary creatinine and albumin were measured using a DCA 2000 microalbumin/creatinine reagent cartridge with a DCA 2000 analyzer (Bayer Corp., Elkhart, IN).

Renal Histopathology

Kidney specimens obtained at 4 and 28 months (n = 5), were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Sections, stained by periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) were used to assess glomerulosclerosis.43 At least 20 glomeruli per slide were chosen for quantification using IP Lab (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) for Macintosh OSX, version 3.9.

Determination of Glutathione (GSH), Oxidized Glutathione (GSSG), and F2-Isoprostanes (8-Isoprostane)

At 4 and 24 months, five animals from each of the diet groups were anesthetized. Whole blood was collected via cardiac puncture and plasma was separated by centrifugation. Levels of GSH and GSSG in whole blood were analyzed colorimetrically (Oxis Research, Portland, OR) using the manufacturer’s recommendations and quantified by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay reader (412 nm).31,41 8-Isoprostane (8-epi-PGF2α) levels were determined in fresh plasma samples, using an enzyme immunoassay kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI).41

Western Blot Analysis: AGER1, RAGE, p66shc

Equal amounts of tissue (kidney cortex, spleen) protein extracts (50 μg) were separated on 10% or 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked in TTBS (Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20) containing 5% powdered milk for 1 hour. Primary antibody incubations were performed in TTBS with 5% powdered milk overnight at 4°C. After washing, the membranes were incubated with the appropriate secondary peroxidase-conjugated antibody for 1 hour in TTBS. Immunoreactive proteins were visualized using the enhanced chemiluminescence system from Roche (Indianapolis, IN). For reprobing, blots were stripped with a buffer containing 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 0.1 mol/L β-mercaptoethanol before probing with a second primary antibody. Primary antibodies were as follows: anti-AGER1 was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) (0.2 μg/ml), anti-RAGE was from Affinity BioReagents (Golden, CO) (1 μg/ml), and anti-p66Shc was from BD Biosciences, Transduction Laboratories (San Jose, CA) (0.25 μg/ml).

Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) Analysis: Transforming Growth Factor (TGF)-β1, Collagen IV

Total RNA was extracted from mouse kidney tissue using TRI Reagent (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and RT-PCR was performed using a kit from Boehringer-Mannheim (Indianapolis, IN). The following primers were used43: TGF-β1 sense: 5′-ATACAGGGCTTTCGATCCAGC-3′; antisense: 5′-GTCCAGGCTCCAAATATAGG-3′. A1 IV collagen sense: 5′-TAGGTGTCAGCAATT AGG-3′: antisense: 5′-TCACTTCAAGCATAGTGGTCCG-3′. PCR products were separated on 1% agarose gel. β-Actin was also performed for each sample as a control of interassay variance. All experiments were repeated at least three times.

Statistics

Mouse survival curves were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method, and statistical differences between these curves were evaluated by the log rank test. Per time point analyses of weight or serum AGEs were performed by one-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. P < 0.05 was defined as significant.

Results

Food Intake and Body Weight

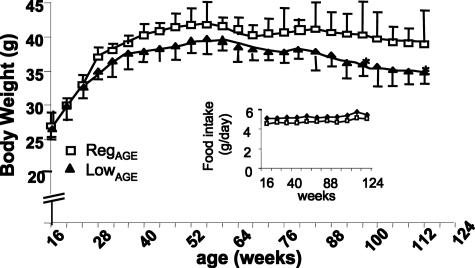

The caloric and nutrient composition of the diets was identical, but the AGE levels were twofold higher in the RegAGE than in the LowAGE diet (Table 1). Food intake by either RegAGE or LowAGE mice stabilized at 5.0 ± 0.27 g/day and remained unchanged throughout the study (Figure 1, inset). The body weight did not differ between the groups, until ∼96 weeks of age, when a modest decline in total weight was noted in LowAGE mice (P < 0.01), despite identical food consumption (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Body weight changes. Mice were exposed to RegAGE or LowAGE diets as per Table 1 (n = 22/group). Food intake (g/day) is shown between 4 and 24 months of age (inset). Data are shown in M ± SEM. After 56 weeks: LowAGE versus RegAGE, *P < 0.001.

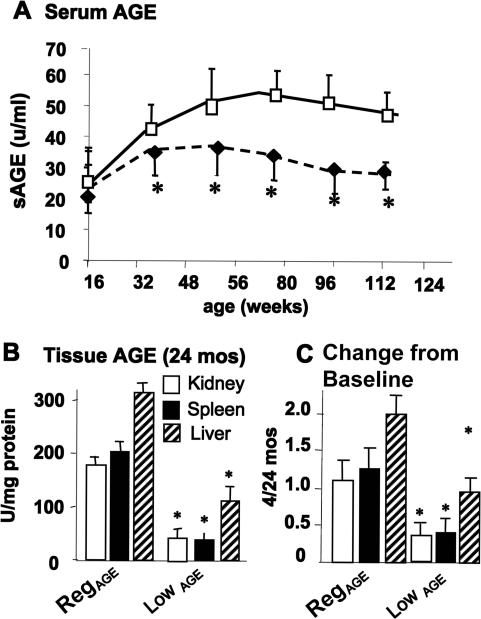

Serum and Tissue AGE

Differences in the dietary content of CML-like AGEs were reflected in the serum and tissue AGE of each cohort. Serum AGE (sAGE) levels in the LowAGE group did not change throughout the study, whereas after 4 months of age sAGE levels increased in the RegAGE group and remained higher throughout the study (P < 0.05) (Figure 2A). The difference in AGE levels between the spleen, kidney cortex, or liver tissues from the two groups of mice at 24 months of age were even more pronounced than in the serum (more than twofold, P < 0.05) (Figure 2, B and C). Similar differences were noted in other tissues (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Serum and tissue AGE levels. A: Serum AGE concentrations in mice pair-fed RegAGE (open symbols) or LowAGE diets (filled symbols). LowAGE versus RegAGE, *P < 0.05. B: Kidney and spleen AGE were assessed at 4 and 24 months of age (n = 8/group). LowAGE versus RegAGE, *P < 0.05. C: Kidney and spleen AGE levels, shown as x-fold above baseline (4 months) (n = 5/group). Data are shown as M ± SEM. LowAGE versus RegAGE, *P < 0.05.

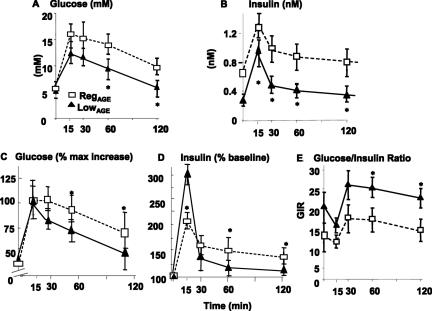

Glucose and Insulin Metabolism

There were no significant differences in fasting blood glucose between the two cohorts, at 4 or 24 months of age (Table 2). Although all mice had elevated plasma insulin at 2 years, RegAGE mice had an ∼3.5-fold higher fasting plasma insulin greater than baseline, 4 months (P < 0.05), and approximately twofold higher than 24-month LowAGE mice (P < 0.01) (Table 2). LowAGE (24 months) mice, however, had a less than 50% increase in fasting insulin from their baseline (P < 0.01) (Table 2). Furthermore, both glucose and insulin responses to intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test, as well as the glucose/insulin ratio (GIR) were markedly impaired in 24-month-old RegAGE mice (Figure 3, A–E). By comparison, 24-month LowAGE mice had nearly normal responses to glucose challenge, ie, insulin returned to baseline levels within 30 minutes (Figure 3, B and D), and the GIR remained within the normal range (twofold more than RegAGE mice) (Figure 3E).

Table 2.

Fasting Plasma Glucose and Insulin Levels in C57BL6 Mice at 4 and 24 Months of Age

| Groups | 4 months

|

24 months

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose (mmol/L) | Insulin (nmol/L) | Glucose (mmol/L) | Insulin (nmol/L) | |

| RegAGE | 6.4 ± 0.5 | 0.16 ± 0.06 | 6.6 ± 1.3 | 0.56 ± 0.2* |

| LowAGE | 5.9 ± 1.3 | 0.17 ± 0.08 | 5.8 ± 0.8 | 0.29 ± 0.04*§ |

P < 0.01 versus 4 months.

P < 0.05 versus age-matched RegAGE group.

Figure 3.

Changes in glucose and insulin response to intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test. Glucose response (A, B), insulin response (C, D), and glucose/insulin ratio (GIR) (E) in RegAGE or LowAGE C57BL6 mice. At 4 and 24 months, after an overnight fast, an intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (5% dextrose solution; 2 mg/g body wt) was performed in subgroups of mice (n = 6) from each diet. Blood samples were taken before and at intervals (15 to 120 minutes) after glucose infusion. A: Differences in glucose levels between LowAGE and RegAGE; B: in percentage from baseline, *P < 0.05 at 60 to 120 minutes; C: in plasma insulin levels; and D: in percentage from baseline, *P < 0.01. E: Glucose-to-insulin (GIR) between LowAGE versus RegAGE at 60 to 120 minutes, *P < 0.01.

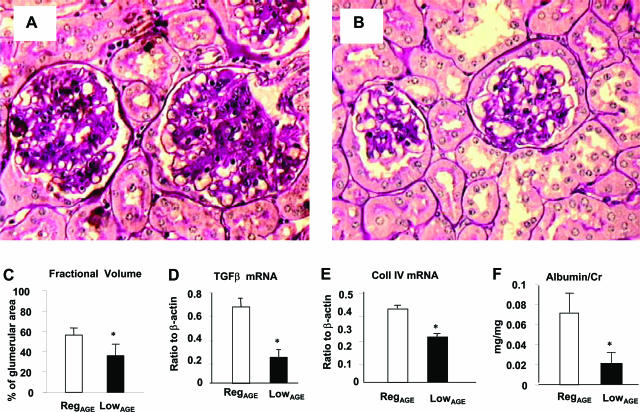

Glomerular Morphology and the Urinary Albumin Excretion Rate

At 24 months, the RegAGE group exhibited more severe glomerulosclerosis (Figure 4, A and B), manifest by an increased fractional mesangial volume per glomerulus (periodic acid-Schiff-positive area ∼58%) (Figure 4C), which was associated with an inflammatory infiltrate. LowAGE mice, had lower fractional mesangial volume (periodic acid-Schiff-positive area ∼38%, P < 0.001) and fewer inflammatory cells in both the glomeruli and interstitium (Figure 4, A and B). The glomerulosclerosis in the RegAGE group was associated with increased levels of TGF-β1 and collagen-IV mRNA relative to LowAGE glomeruli (P < 0.05) (Figure 4, D and E). The RegAGE group also had interstitial inflammatory cell infiltrates and fibrosis, which was associated with tubular atrophy and thickening of the tubular basement membranes (Figure 4A). These histological changes were associated with changes in the albumin excretion rate in both groups of 24-month-old mice. However, compared with RegAGE mice, the LowAGE group had a significantly lower albumin excretion rate (P < 0.05) (Figure 4F), consistent with the lower levels of serum and kidney AGEs in this group (Figure 2, A–C).

Figure 4.

Changes in glomeruli and renal function. Morphology of renal cortex from RegAGE (A) and LowAGE mice (B), n = 6/group (periodic acid-Schiff). C: Fractional mesangial volume (*P < 0.05). D: TGF-β (P < 0.05) and E: collagen type IV mRNA levels in RegAGE versus LowAGE (*P < 0.05). F: Albumin/creatinine ratio (*P < 0.05). Data are shown as M ± SEM of triplicate values. Original magnifications, ×200.

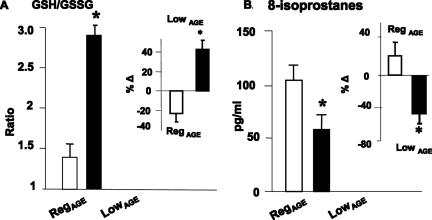

GSH/GSSG Ratio and Plasma 8-Isoprostane Levels

Comparison of GSH and GSSG levels in fresh blood cells from each group revealed a significantly higher GSH/GSSG ratio in LowAGE mice, compared with RegAGE mice at 24 months (Figure 5A) (P < 0.001). At 24 months, the intracellular GSH/GSSG ratio in RegAGE was reduced ∼25% below the 4-month baseline level (Figure 5A, inset). In contrast, in 24-month LowAGE mice, the GSH/GSSG ratio was elevated by ∼40% above that at 4 months (baseline) (Figure 5A and inset). Furthermore, at 24 months the levels of endogenous lipid peroxidation products, plasma 8-isoprostanes were higher in RegAGE mice, compared with LowAGE (P < 0.01) (Figure 5B). Of note, in the 24-month LowAGE group, 8-isoprostanes were ∼45% lower than at the 4-month baseline (P < 0.02), whereas in RegAGE mice they were ∼20% higher than at baseline (Figure 5B, inset).

Figure 5.

Changes in OS indicators. A: GSH/GSSG ratio. Levels of GSH and GSSG were measured in whole blood at 4 (baseline) and 24 weeks of age (n = 6/group). RegAGE versus LowAGE mice. **P < 0.001. The relative change from baseline is shown in the inset. B: Plasma levels of isoprostane 8-epi-PGF2α are shown as M ± SEM pg/ml (n = 6/group). RegAGE versus LowAGE, **P < 0.01. The relative change from baseline is shown in the inset.

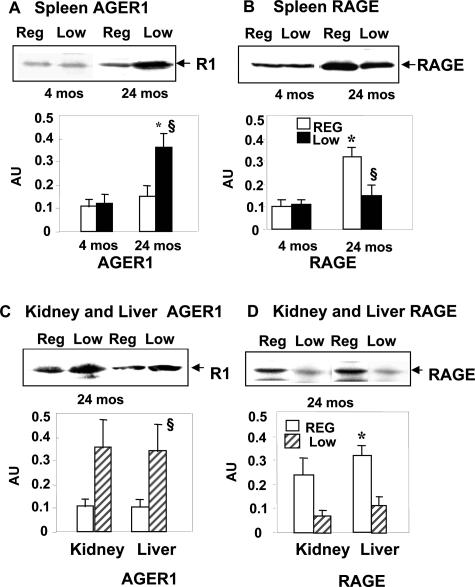

AGER1, RAGE, and p66shc

The tissue expression of AGE receptors was assessed in spleen, kidney, and liver from young (4 months) and old (24 months) mice (Figure 6). AGER1 protein levels in old LowAGE mouse spleen tissue was increased by threefold, compared with age-matched and 4-month RegAGE mice (P < 0.01 versus 4-month RegAGE; P < 0.01 versus 24-month RegAGE) (Figure 6A). In fact, AGE-R1 expression in 24-month RegAGE mouse tissues was as low as at 4 months. By comparison, RAGE expression in these mice was 3.5-fold higher than at 4 months of age (P < 0.01) (Figure 6B). However, RAGE levels in old LowAGE mice were significantly lower than in old RegAGE (P < 0.01) and did not different from those at 4 months (Figure 6B). Similar differences were noted in kidney and liver tissues (Figure 6, C and D).

Figure 6.

Levels of AGER1 and RAGE. AGER1 (A) and RAGE (B) protein levels were assessed in spleen tissues from RegAGE and LowAGE mice (n = 6/group) at 4 and 24 months. AGER1 expression (C) in kidney and liver and RAGE expression (D) in kidney and liver of the same mouse groups were also assessed at 24 months by Western blotting and densitometric analysis. Data are shown as M ± SEM of three independent experiments (*P < 0.01 versus 4-month RegAGE; §P < 0.01 versus 24-month RegAGE).

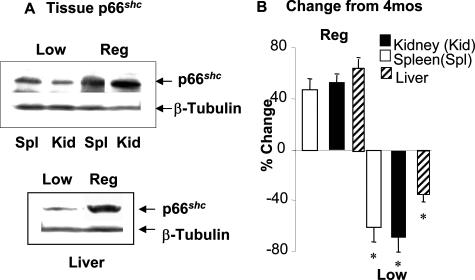

Protein levels of p66shc, an adaptor molecule implicated in oxidant injury and lifespan,13,14 were also examined in kidney, spleen, and liver tissues of young and aging mice exposed to the two diets (Figure 7, A and B). The expression of p66shc in old LowAGE mice was significantly lower than in old RegAGE or the 4-month baseline (∼55 to 60%; P < 0.01, respectively). This was in direct contrast to the 24-month RegAGE mice, which had an increase in p66shc (∼40 to 50%) greater than the 4-month baseline (P < 0.01) (Figure 7, A and B).

Figure 7.

Levels of p66shc protein in kidney, spleen, and liver tissues (n = 6/group). Western blots (A) and densitometry data (B) also indicate relative change from 4 months of age (baseline). Data shown are M ± SEM of three independent experiments (n = 6/group, *P < 0.01).

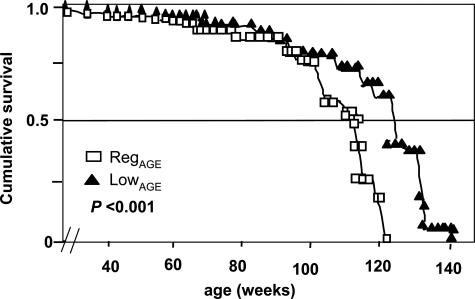

Survival

Median and maximal survival (at 10th percentile) of each group are shown in Figure 8 and Table 3, along with all lifespan percentiles. Lifespan in LowAGE mice was longer than in RegAGE (median, 15%; maximal, 6%, respectively; P < 0.001). At the median survival for RegAGE, 75% of LowAGE mice were alive, whereas at the maximal survival level for RegAGE, 40% of LowAGE mice were alive.

Figure 8.

Survival. Kaplan-Meier survival curves in RegAGE mice (open squares) and LowAGE mice (filled triangles) (n = 22/group). Lifespan of the LowAGE group was significantly longer than in RegAGE (P < 0.001). Differences between the curves were estimated by the log rank test.

Table 3.

Lifespan Percentiles

| Median

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max | 90% | 75% | 50% | 25% | Mean ± SE | Log rank | |

| RegAGE | 121 | ∼120 | 117 | 108 | 89 | 102.7 ± 4.2 | 6.9 |

| LowAGE | 137 | ∼129 | 127 | 121 | 104 | 112.9 ± 4.7 | −11.2 |

LowAGE versus RegAGE: P < 0.001.

Discussion

The mice exposed to a low-glycoxidant (RegAGE) diet had reduced levels of OS, less severe age-related metabolic and kidney changes, and a longer lifespan, relative to mice exposed to an isocaloric diet of standard AGE content (LowAGE). The findings suggest that avoidance of certain thermally induced oxidants in the standard diet, such as oxidant AGEs, may be beneficial. The expression and function of AGER1, a receptor responsible for AGE removal and degradation of AGEs, was enhanced in several key organs of LowAGE mice, but not of RegAGE mice. Preservation of AGER1 function may have involved the negative regulation of the pro-oxidant RAGE, and lifespan-related p66sch proteins. In combination with a reduced oxidant AGE intake, such a novel pathway may have contributed to the prevention in the decline of innate defense mechanisms and the appearance of organ failure in these aging mice.

The C57BL6 male mice given the RegAGE diet appeared normal throughout the study. Their weight reached a plateau in adulthood and remained constant, whereas the mean body weight of the LowAGE mice declined slightly at the end of the study. Because a significant reduction in caloric intake (∼40%) is required for the lifespan extension observed in this study,1 the late and modest differences in body weight of these pair-fed mice could not be attributed to a significantly different energy intake, pointing to other factor(s), including the levels of oxidants. Age-related weight gain or retention is associated with increased intra-abdominal fat and insulin resistance, despite the concurrent loss of muscle mass attributable to both a decrease in physical activity and the effects of aging.44 Therefore, the impaired glucose and insulin responses in 24-month RegAGE mice could be attributable to increased fat stores. The 24-month LowAGE mice had a pattern of glucose and insulin utilization similar to that of 4-month mice, consistent with an absence of age-related excess fat. A dissociation between energy intake and body weight was previously observed in mice pair-fed fed high-fat diets that varied only in AGE content and in normal adults.41,44,45 The RegAGE, high-fat mice weighed more and had larger abdominal fat stores, containing higher levels of AGE-modified lipids and were less insulin sensitive than mice fed a LowAGE, high-fat diet. Consistent with that study, the current differences in weight could not be explained by differences in food intake because the mice were pair fed. The modest differences in body weight may also be related to a difference in the rate of turnover of AGE fat in the RegAGE diet group, compared with the LowAGE mice. Because AGEs stimulate the production of proinflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α,46 which may promote insulin resistance,47,48 the greater tissue AGE burden in RegAGE mice might have contributed to the age-related impaired glucose, insulin, and fat utilization. The attenuation of these metabolic events in aged LowAGE mice in the current study was consistent with the lower AGE intake and tissue AGE deposits.

The significant differences in kidney disease severity between 24-month RegAGE and LowAGE mice provide further support for the hypothesis that the high levels of oxidant AGEs in the normal diet promote tissue injury. The CKD of aging, like cardiovascular disease and the metabolic syndrome, is associated with increased OS.49 CKD is also a major contributor to cardiovascular disease, often preceding vascular decline. Several strains of mice manifest severe CKD with aging, including C57BL6 mice.50,51 We previously found that the kidneys of 24-month RegAGE C57BL6 mice had increased glomerulosclerosis and albuminuria, as well as stable phenotypic changes in isolated mesangial cells, and that these changes were transferred by bone marrow transplantation to naïve young recipients.51 The current study shows that reduced AGE intake by a LowAGE diet prevented the CKD of aging. The effects of a high or low AGE intake on tissue injury are not restricted to aging because similar effects have been observed in studies of diabetes-related kidney or vascular disease and wound healing.38,52

The age-related decrease of GSH:GSSG ratio in the 24-month RegAGE mice, in addition to reflecting an excess in total intracellular reactive oxygen species production, may provide a direct link between increased OS and organ decline, metabolic changes, and lifespan during aging. This possibility was supported by the increase in endogenous lipid peroxidation products, ie, 8-isoprostanes, as well as in pro-oxidant AGEs. These changes were not observed in LowAGE mice, which maintained a strong anti-oxidant balance throughout life. These data suggest that depletion of antioxidant stores during aging of experimental mice, and possibly humans, may result from chronic overexposure to oxidants derived from the normal Western diet. This hypothesis is supported by a recent study in normal, ambulatory patients.45

Cellular responses to AGEs depend on at least two general types of receptors, which have opposing actions. RAGE exemplifies the class that promotes OS.22,23,53 AGER1 is a member of a group that mediates removal and detoxification of AGEs, resulting in suppression of OS.17,54,55 In this study, AGER1 expression in tissues from 24-month LowAGE mice was more than threefold higher than at initiation of the study (4 months). This was accompanied by a marked increase in anti-oxidant reserves and lower levels of tissue AGEs, RAGE, and other native oxidants, ie, 8-isoprostanes. We have previously shown that AGEs can up-regulate cellular AGE uptake22 and that this is at least partly AGER1 mediated.17 The increased expression of AGER1 in the LowAGE mice suggests that AGER1 can respond to fluctuations in AGE load in vivo, if this load does not exceed a certain threshold, which remains to be defined. The current study also demonstrates that if the external AGE burden is moderated, ie, with a low AGE diet, AGER1 levels remain responsive to AGE increases, ie, because of aging, leading to effective control of tissue AGE as well as of OS. In contrast, under conditions of chronically excessive exogenous AGE, AGER1 levels, like other anti-oxidant defenses, fail to respond, indicating that the capacity of the body to handle oxidants was exceeded. Sustained exposure to high AGE levels, and other oxidants, may lead to a down-regulation of other receptor systems, eg, scavenger receptor B, or CD36,56,57 further contributing to high OS during aging. Of interest, increased tissue AGER1 expression in old LowAGE mice, matched by a lower RAGE, serve as additional in vivo evidence that AGER1 may contribute to the regulation of RAGE in vivo.17,54

Of interest, in the context of the current study, were the changes observed in the expression of p66shc, an OS-regulatory adaptor protein11,12 that has been negatively linked to longevity.11 Tissue p66shc levels were increased in 24-month RegAGE (40 to 50%) compared with the values at 4 months of age. In contrast, p66shc levels were significantly decreased in 24-month LowAGE mice (∼60% less than at 4 months). This decrease in p66shc involved multiple tissues and was commensurate with the reduced OS levels in 24-month LowAGE mice, as well as with the reduction in the severity of kidney disease in this group. A similar protection was reported against renal/vascular tissue injury in p66shc mutant mice.58,59 The inverse correlation between low p66shc and increased AGER1 levels in LowAGE mice may be partly explained on the basis of an AGER1-mediated inhibition of the EGFR signaling pathway,54 because the activation of this pathway involves p66shc.60 The fact that AGER1 may act to prevent the induction of p66Shc could provide a new mechanistic link between AGER1 stimulation and p66shc suppression. Although further studies are required to fully explain these events, such an interaction may have contributed to extended lifespan in LowAGE mice. The increased AGER1 expression, combined with reduced AGE, OS, RAGE, and p66Shc levels in LowAGE mice does not prove a causal relationship, but it suggests that homeostatic mechanisms might be able to better compensate in older age, if exogenous oxidants did not exceed the body’s inherent capacity to take up, degrade, and excrete these compounds. Interestingly, soluble RAGE, which binds circulating AGEs, was recently found to be elevated in the healthy elderly.61

In summary, the current study suggests that age-related changes in OS, glucose and insulin metabolism, renal injury, and lifespan in normal mice are events that can be modulated by the degree of exposure to external (dietary) oxidants. Although restricting AGE intake can be immediately tested in humans as a single intervention,37,40 future studies may also examine the combined effects of low AGE diets with other dietary and therapeutic interventions.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Helen Vlassara, M.D., Mount Sinai School of Medicine, Box 1640, One Gustave Levy Place, New York, NY 10029. E-mail: helen.vlassara@mssm.edu.

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (National Institute on Aging grant AG00943 and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grant DK054788 to H.V.).

References

- Masoro EJ. Overview of caloric restriction and ageing. Mech Ageing Dev. 2005;126:913–922. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quarrie JK, Riabowol KT. Murine models of lifespan extension. Sci Aging Knowledge Environ. 2004;(31):re5. doi: 10.1126/sageke.2004.31.re5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen MA, Hsieh CC, Boylston WH, Flurkey K, Harrison D, Papaconstantinou J. Altered oxidative stress response of the long-lived Snell dwarf mouse. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;318:998–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman JA, Malloy V, Krajcik R, Orentreich N. Nutrition control of aging. Exp Gerontol. 2003;38:47–52. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(02)00149-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaeberlein M, Hu D, Kerr EO, Tsuchiya M, Westman EA, Dang N, Fields S, Kennedy BK. Increased life span due to caloric restriction in respiratory-deficient yeast. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:614–621. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokov A, Chaudhuri A, Richardson A. The role of oxidative damage and stress in aging. Mech Ageing Dev. 2004;125:811–826. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo VD, Finch CE. Evolutionary medicine: from dwarf model systems to healthy centenarians. Science. 2003;299:1342–1346. doi: 10.1126/science.1077991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RM, Latorre-Esteves M, Neves AR, Lavu S, Medvedik O, Taylor C, Howitz KT, Santos H, Sinclair DA. Yeast life-span extension by caloric restriction is independent of NAD fluctuation. Science. 2003;302:2124–2124. doi: 10.1126/science.1088697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimokawa I, Higami Y, Tsuchiya T, Otani H, Komatsu T, Chiba T, Yamaza H. Life span extension by reduction of the growth hormone-insulin-like growth factor-1 axis: relation to caloric restriction. FASEB J. 2003;17:1108–1109. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0819fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzenberger M, Dupont J, Ducos B, Leneuve P, Geloen A, Even PC, Cervera L, Le Bouc Y. IGF-1 receptor regulates lifespan and resistance to oxidative stress in mice. Nature. 2003;421:182–187. doi: 10.1038/nature01298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migliaccio E, Giorgio M, Mele S, Pelicci G, Reboldi P, Pandolfi PP, Lanfrancone L. The p66shc adaptor protein controls oxidative stress response and life span in mammals. Nature. 1999;402:309–313. doi: 10.1038/46311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto S, Finkel T. Redox regulation of forkhead proteins through a p66shc-dependent signaling pathway. Science. 2002;295:2450–2452. doi: 10.1126/science.1069004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schriner SE, Linford NJ, Martin GM, Treuting P, Ogburn CE, Emond M, Coskun PE, Ladiges W, Wolf N, Van Remmen H, Wallace DC, Rabinovitch PS. Extension of murine life span by overexpression of catalase targeted to mitochondria. Science. 2005;308:1909–1911. doi: 10.1126/science.1106653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melov S, Ravenscroft J, Malik S, Gill MS, Walker DW, Clayton PE, Wallace DC, Malfroy B, Doctrow SR, Lithgow GJ. Extension of life-span with superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetics. Science. 2000;289:1567–1569. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5484.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Requena JR, Ahmed MU, Fountain CW, Degenhardt TP, Reddy S, Perez C, Lyons TJ, Jenkins AJ, Baynes JW, Thorpe SR. Carboxymethylethanolamine, a biomarker of phospholipid modifications during the Maillard reaction in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17473–17479. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownlee M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature. 2001;414:813–820. doi: 10.1038/414813a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, He JC, Cai W, Liu H, Zhu L, Vlassara H. Advanced glycation endproduct (AGE) receptor 1 is a negative regulator of the inflammatory response to AGE in mesangial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:11767–11772. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401588101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makita Z, Radoff S, Rayfield EJ, Yang Z, Skolnik E, Delaney V, Friedman EA, Cerami A, Vlassara H. Advanced glycosylation endproducts in patients with diabetic nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:836–842. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199109193251202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlassara H, Moldawer L, Chan B. Macrophage/monocyte receptor for non-enzymatically glycosylated proteins is up-regulated by cachectin/tumor necrosis factor. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:1813–1820. doi: 10.1172/JCI114366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C, Koschinsky T, Buenting C, Vlassara H. Presence of diabetic complications in type I diabetic patients correlates with low expression of mononuclear cell AGE-receptor-1 and elevated serum AGE. Mol Med. 2001;7:159–168. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R, Barden A, Mori T, Beilin L. Advanced glycation end-products: a review. Diabetologia. 2001;44:129–146. doi: 10.1007/s001250051591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlassara H, Uribarri J. Glycoxidation and diabetic complications: modern lesson and a warning? Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2004;5:181–188. doi: 10.1023/B:REMD.0000032406.84813.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt AM, Yan SD, Yan SF, Stern DM. The multiligand receptor RAGE as a progression factor amplifying immune and inflammatory responses. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:949–955. doi: 10.1172/JCI14002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HX, Zheng F, Cao Q, Ren B, Zhu L, Striker G, Vlassara H. Amelioration of oxidant stress by the defensin lysozyme. Am J Physiol. 2006;290:E824–E832. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00349.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao D, Taguchi T, Matsumura T, Pestell R, Edelstein D, Giardino I, Suske G, Ahmed N, Thornalley PJ, Sarthy VP, Hammes HP, Brownlee M. Methylglyoxal modification of mSin3A links glycolysis to angiopoietin-2 transcription. Cell. 2006;124:275–286. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monnier VM, Sell DR, Genuth S. Glycation products as markers and predictors of the progression of diabetic complications. The Maillard Reaction, Chemistry at the Interface of Nutrition, Aging, and Disease. Baynes JW, Monnier VM, Ames JM, Thorpe SR, editors. 2005 doi: 10.1196/annals.1333.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien J. Nutritional and toxicological aspects of the Maillard browning reaction in foods. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 1989;28:211–248. doi: 10.1080/10408398909527499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birlouez-Aragon I, Pischetsrieder M, Leclere J, Morales FJ, Hasenkopf K, Kientsch-Engel R, Ducauze CJ, Rutledge D. Assessment of protein glycation markers in infant formulas. Food Chem. 2004;87:253–259. [Google Scholar]

- Glomb MA, Schirnich RT. Detection of alpha-dicarbonyl compounds in Maillard reaction systems and in vivo. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49:5543–5550. doi: 10.1021/jf010148h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Boekel MA. Kinetic aspects of the Maillard reaction: a critical review. Nahrung. 2001;45:150–159. doi: 10.1002/1521-3803(20010601)45:3<150::AID-FOOD150>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai W, Gao QD, Zhu L, Peppa M, He C, Vlassara H. Oxidative stress-inducing carbonyl compounds from common foods: novel mediators of cellular dysfunction. Mol Med. 2002;8:337–346. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng K, Chen F, Wang M. Heterocyclic amines: chemistry and health. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2006;50:1150–1170. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200600086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C, Sabol J, Mitsuhashi T, Vlassara H. Dietary glycotoxins: inhibition of reactive products by aminoguanidine facilitates renal clearance and reduces tissue sequestration. Diabetes. 1999;48:1308–1315. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.6.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CW, Vlassara H, Striker GE, Striker LJ. Administration of AGEs in vivo induces genes implicated in diabetic glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 1995;49:S55–S58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CW, Hattori M, Vlassara H, He CJ, Carome MA, Yamato E, Elliot S, Striker GE, Striker LJ. Overexpression of TGF-β1 mRNA is associated with upregulation of glomerular tenascin and laminin gene expression in diabetic NOD mice. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1995;5:1610–1617. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V581610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YM, Steffes M, Donnelly T, Liu C, Fuh H, Basgen J, Bucala R, Vlassara H. Prevention of cardiovascular and renal pathology of aging by the advance glycation inhibitor aminoguanidine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3902–3907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.3902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlassara H, Cai W, Crandall J, Goldberg T, Oberstein R, Dardaine V, Peppa M, Rayfield EJ. Inflammatory mediators are induced by dietary glycotoxins, a major risk factor for diabetic angiopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15596–15601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242407999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin RY, Choudhury RP, Cai W, Lu M, Fallon JT, Fisher EA, Vlassara H. Dietary glycotoxins promote diabetic atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Atherosclerosis. 2003;168:213–220. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(03)00050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koschinsky T, He CJ, Mitsuhashi T, Bucala R, Liu C, Buenting C, Heitmann K, Vlassara H. Orally absorbed reactive glycation products (glycotoxins): an environmental risk factor in diabetic nephropathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6474–6479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uribarri J, Peppa M, Cai W, Goldberg T, Lu M, He C, Vlassara H. Restriction of dietary glycotoxins reduces excessive advanced glycation end products in renal failure patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:728–731. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000051593.41395.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandu O, Song K, Cai W, Zheng F, Uribarri J, Vlassara H. Insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes in high-fat-fed mice are linked to high glycotoxin intake. Diabetes. 2005;54:2314–2319. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.8.2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SM, Dong HJ, Li Z, Cai W, Altomonte J, Thung SN, Zeng F, Fisher EA, Vlassara H. Improved insulin sensitivity is associated with restricted intake of dietary glycoxidation products in the db/db mouse. Diabetes. 2002;51:2082–2089. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.7.2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng F, He C, Cai W, Hattori M, Steffes M, Vlassara H. Prevention of diabetic nephropathy in mice by a diet low in glycoxidation products. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2002;18:224–237. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peppa M, Brem H, Ehrlich P, Zhang J, Cai W, Zhu L, Croitoru A, Thung S, Vlassara H. Adverse effects of dietary glycotoxins on wound healing in genetically diabetic mice. Diabetes. 2003;52:2805–2813. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.11.2805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uribarri J, Cai W, Peppa M, Goodman S, Ferrucci L, Striker G, Vlassara H. Circulating glycotoxins and dietary AGEs; two links to inflammatory response, oxidative stress and aging. J Gerontology. 2007;62A:428–434. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.4.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changani KK, Nicholson A, White A, Latcham JK, Reid DG, Clapham JC. A longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study of differences in abdominal fat distribution between normal mice, and lean overexpressors of mitochondrial uncoupling. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2003;5:99–105. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1326.2003.00249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss MF, Erhard P, Kader-Attia FA, Wu YC, Deoreo PB, Araki A, Glomb MA, Monnier VM. Mechanisms for the formation of glycoxidation products in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2000;57:2571–2585. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H, Kokoeva MV, Inouye K, Tzameli I, Yin H, Flier JS. TLR4 links innate immunity and fatty acid-induced insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3015–3025. doi: 10.1172/JCI28898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arkan MC, Hevener AL, Greten FR, Maeda S, Li ZW, Long JM, Wynshaw-Boris A, Poli G, Olefsky J, Karin M. IKK-beta links inflammation to obesity-induced insulin resistance. Nat Med. 2005;11:191–198. doi: 10.1038/nm1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basta G, Lazzerini G, Turco SD, Ratto GM, Schmidt AM, Caterina RD. At least 2 distinct pathways generating reactive oxygen species mediate vascular cell adhesion moleucule-1 induction by advanced glycation end products. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1401–1407. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000167522.48370.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng F, Chen QL, Plati AR, Ye SQ, Berho M, Banerjee A, Potier M, Jaimes E, Guan YF, Hao CM, Striker LJ, Striker GE. The glomerulosclerosis of aging: contribution of the proinflammatory mesangial cell phenotype to macrophage infiltration. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1789–1798. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63434-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z, Plati AR, Chen QL, Berho M, Banerjee A, Potier M, Wen-che J, Koff A, Striker LJ, Striker GE. Glomerular aging in females is a multi-stage reversible process mediated by phenotypic changes in progenitors. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:355–362. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62981-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basta G, Lazzerini G, Massaro M, Simoncini T, Tanganelli P, Fu C, Kislinger T, Stern DM, Schmidt AM, De Caterina R. Advanced glycation end products activate endothelium through signal-transduction receptor RAGE: a mechanism for amplification of inflammatory responses. Circulation. 2002;105:816–822. doi: 10.1161/hc0702.104183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai W, He JC, Zhu L, Lu C, Vlassara H. Advanced glycation end product (AGE) receptor 1 suppresses cell oxidant stress and activation signaling via EGF receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13801–13806. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600362103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C, Zheng F, Stitt A, Striker L, Hattori M, Vlassara H. Differential expression of renal AGE-receptor genes in NOD mouse kidneys: possible role in non-obese diabetic renal disease. Kidney Int. 2000;58:1931–1940. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2000.00365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazio S, Linton MF. Interplay between apolipoprotein E and scavenger receptor class B type I controls coronary atherosclerosis and lifespan in the mouse. Circulation. 2005;111:3349–3351. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.545996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwasako T, Hirano K, Sakai N, Ishigami M, Hireoka H, Yakub MJ, Takihara KY, Yamashita S, Matsuzawa Y. Lipoprotein abnormalities in human genetic CD36 deficiency associated with insulin resistance and abnormal fatty acid metabolism. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1647–1648. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.5.1647-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menini S, Amadio L, Oddi G, Ricci G, Pesce G, Pugliese F, Giorgio M, Migliaccio E, Pelicci P, Lacobini C, Pugliese G. Deletion of p66shc longevity gene protects against experimental diabetic glomerulopathy by preventing diabetes-induced oxidative stress. Diabetes. 2006;55:1642–1650. doi: 10.2337/db05-1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napoli C, Padura IM, Nigris FD, Giorgio M, Mansueto G, Somma P, Condorelli M, Sica G, Rosa GD, Pelicci P. Deletion of the p66shc longevity gene reduces systemic and tissue oxidative stress, vascular cell apoptosis, and early atherogenesis in mice fed a high-fat diet. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:2112–2116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0336359100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Nagao T, Kakumoto M, Kimoto M, Otsuki T, Iwasaki T, Tokmakov AA, Owada K, Fukami Y. Adaptor protein Shc is an isoform-specific direct activator of the tyrosine kinase c-Src. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29568–29576. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203179200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geroldi D, Falcone C, Minoretti P, Emanuele E, Arra M, D’Angelo A. High levels of soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products may be a marker of extreme longevity in humans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1149–1150. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]