Abstract

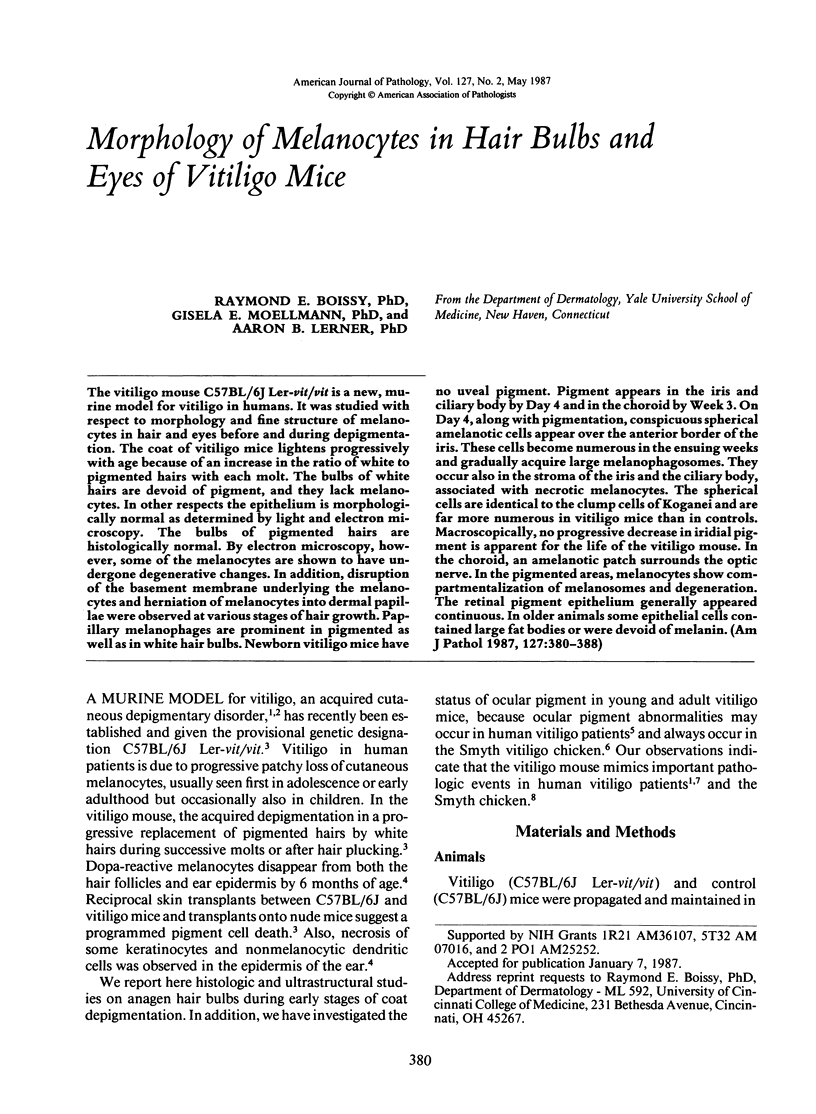

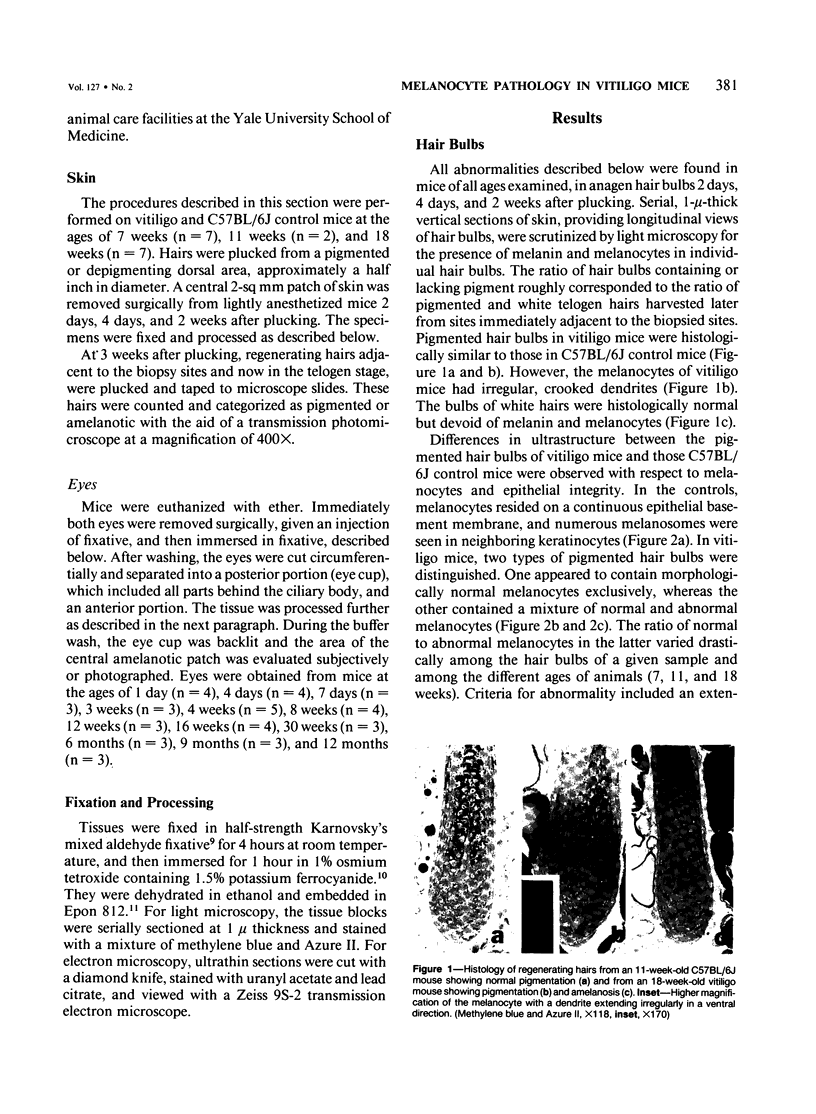

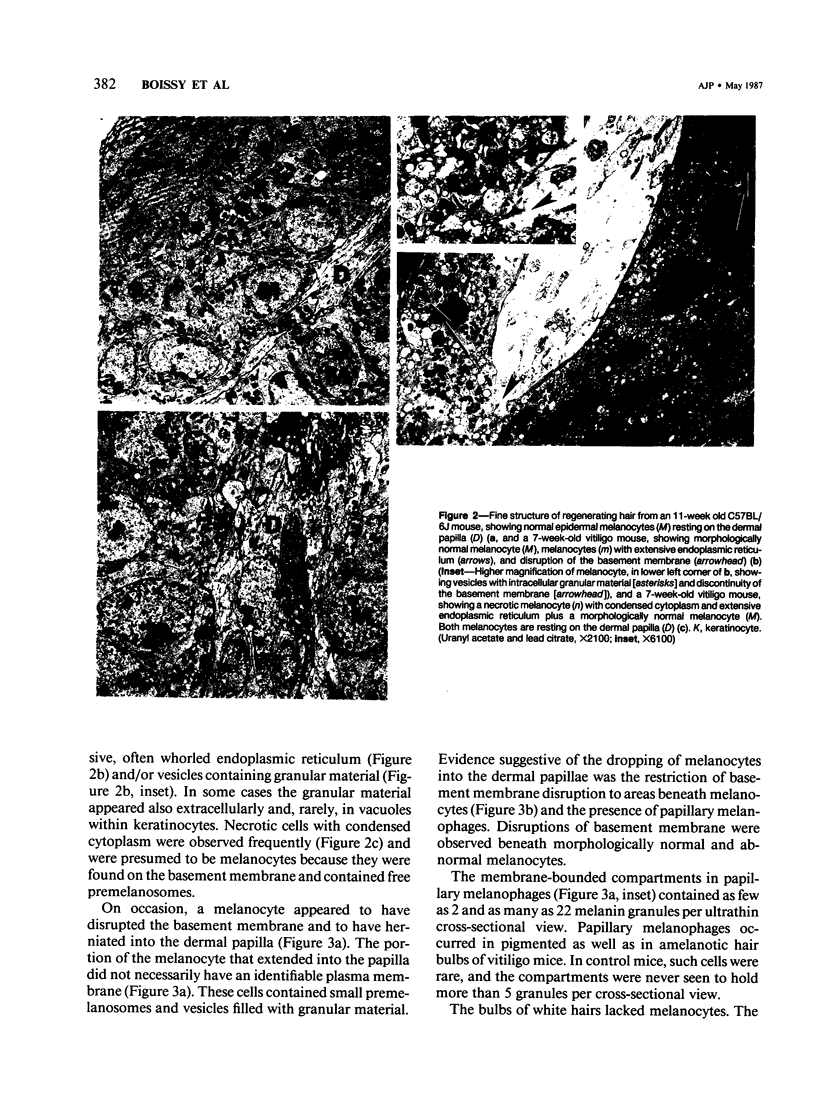

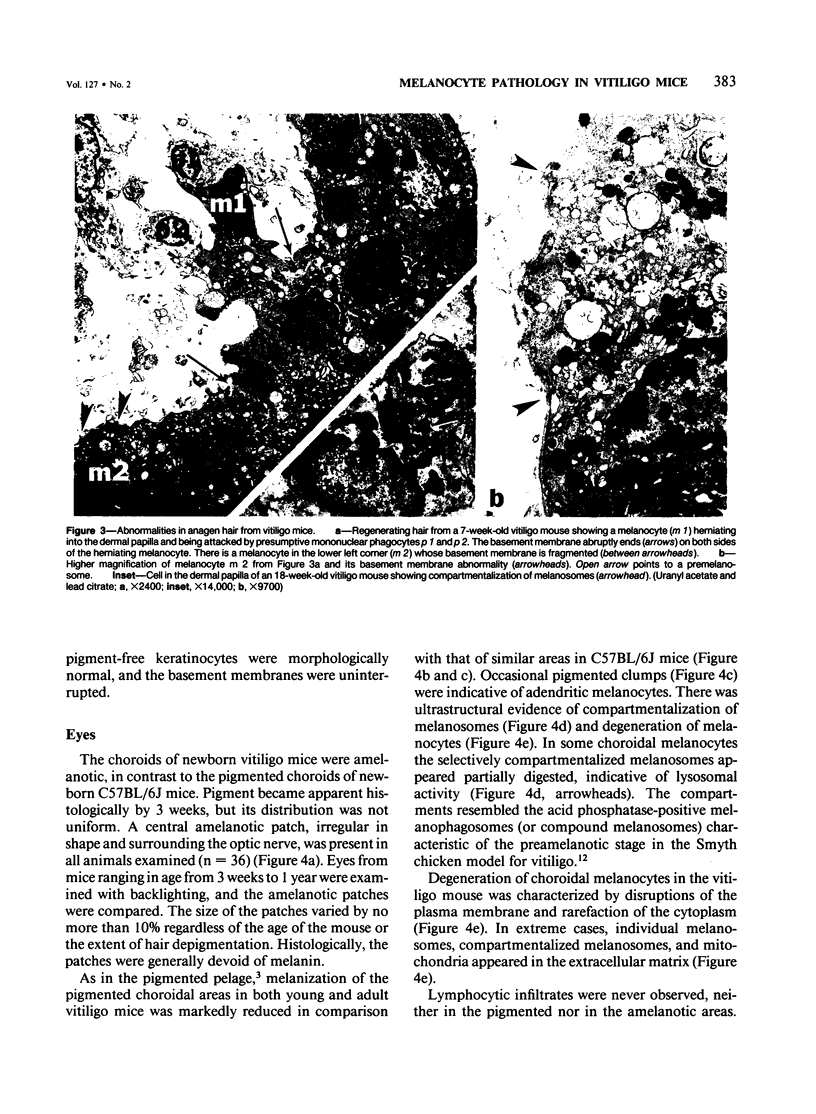

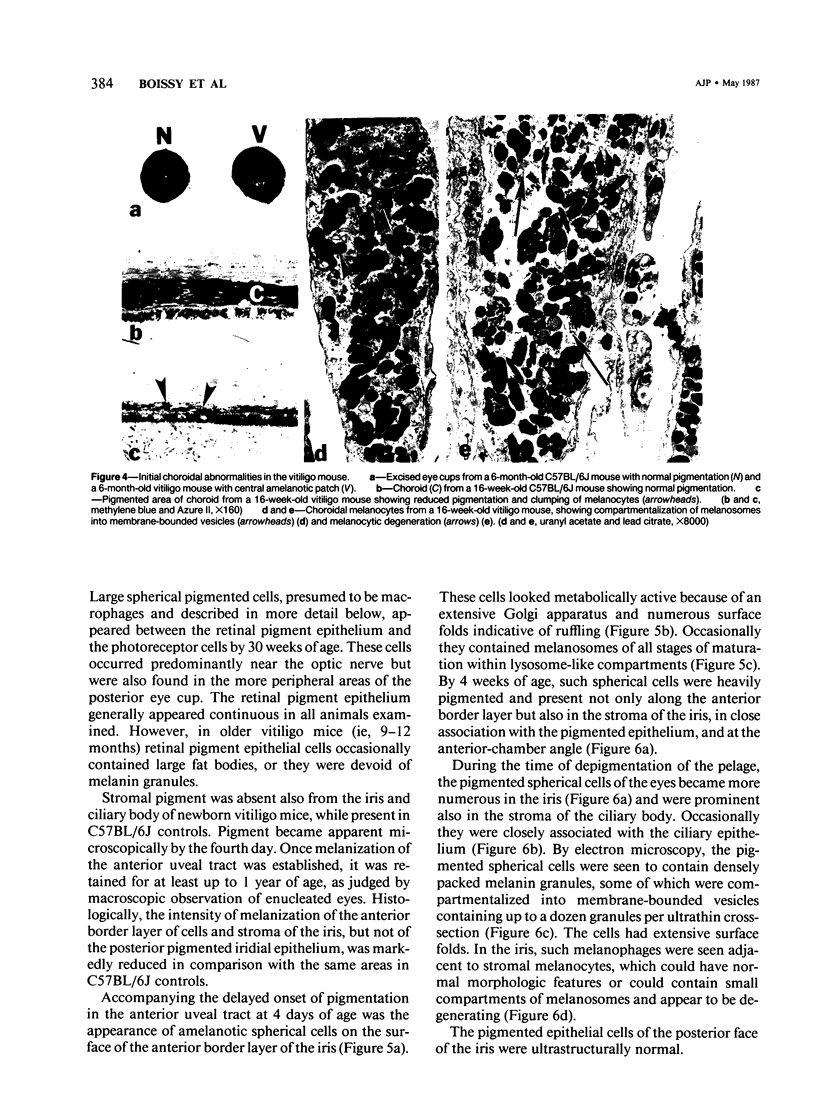

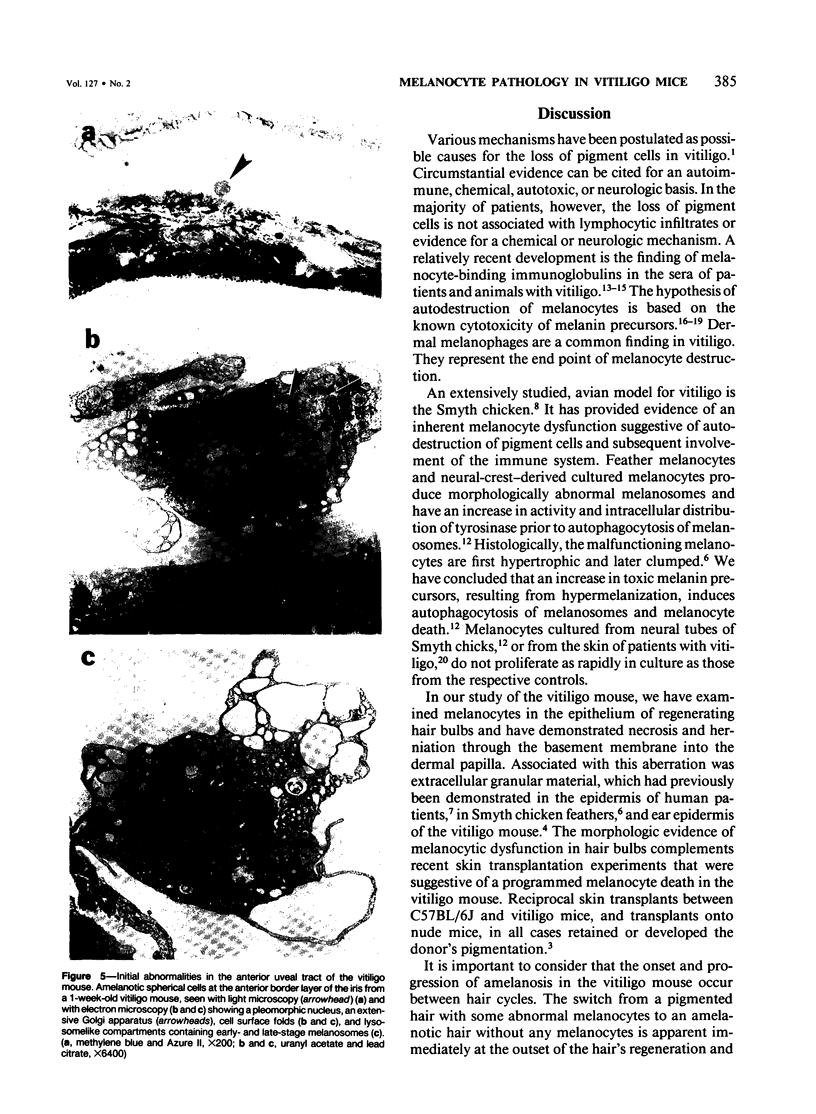

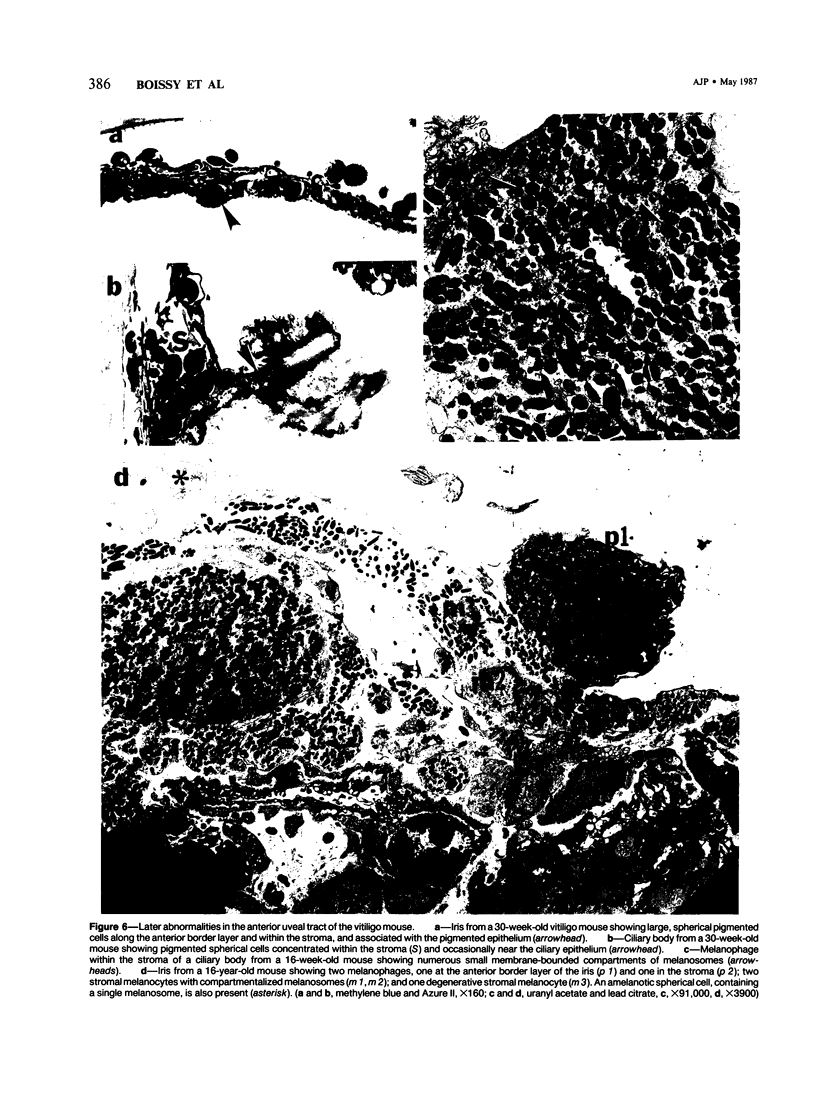

The vitiligo mouse C57BL/6J Ler-vit/vit is a new, murine model for vitiligo in humans. It was studied with respect to morphology and fine structure of melanocytes in hair and eyes before and during depigmentation. The coat of vitiligo mice lightens progressively with age because of an increase in the ratio of white to pigmented hairs with each molt. The bulbs of white hairs are devoid of pigment, and they lack melanocytes. In other respects the epithelium is morphologically normal as determined by light and electron microscopy. The bulbs of pigmented hairs are histologically normal. By electron microscopy, however, some of the melanocytes are shown to have undergone degenerative changes. In addition, disruption of the basement membrane underlying the melanocytes and herniation of melanocytes into dermal papillae were observed at various stages of hair growth. Papillary melanophages are prominent in pigmented as well as in white hair bulbs. Newborn vitiligo mice have no uveal pigment. Pigment appears in the iris and ciliary body by Day 4 and in the choroid by Week 3. On Day 4, along with pigmentation, conspicuous spherical amelanotic cells appear over the anterior border of the iris. These cells become numerous in the ensuing weeks and gradually acquire large melanophagosomes. They occur also in the stroma of the iris and the ciliary body, associated with necrotic melanocytes. The spherical cells are identical to the clump cells of Koganei and are far more numerous in vitiligo mice than in controls. Macroscopically, no progressive decrease in iridial pigment is apparent for the life of the vitiligo mouse. In the choroid, an amelanotic patch surrounds the optic nerve. In the pigmented areas, melanocytes show compartmentalization of melanosomes and degeneration. The retinal pigment epithelium generally appeared continuous. In older animals some epithelial cells contained large fat bodies or were devoid of melanin.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Albert D. M., Nordlund J. J., Lerner A. B. Ocular abnormalities occurring with vitiligo. Ophthalmology. 1979 Jun;86(6):1145–1160. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(79)35413-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boissy R. E., Lamont S. J., Smyth J. R., Jr Persistence of abnormal melanocytes in immunosuppressed chickens of the autoimmune "DAM" line. Cell Tissue Res. 1984;235(3):663–668. doi: 10.1007/BF00226966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boissy R. E., Moellmann G., Trainer A. T., Smyth J. R., Jr, Lerner A. B. Delayed-amelanotic (DAM or Smyth) chicken: melanocyte dysfunction in vivo and in vitro. J Invest Dermatol. 1986 Feb;86(2):149–156. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12284190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boissy R. E., Smyth J. R., Jr, Fite K. V. Progressive cytologic changes during the development of delayed feather amelanosis and associated choroidal defects in the DAM chicken line. A vitiligo model. Am J Pathol. 1983 May;111(2):197–212. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter H. D. Rapid and improved methods fr embedding biological tissues in Epon 812 and Araldite 502. J Ultrastruct Res. 1967 Oct 31;20(5):346–355. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(67)80104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOCHSTEIN P., COHEN G. The cytotoxicity of melanin precursors. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1963 Feb 15;100:876–886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halaban R., Lerner A. B. Tyrosinase and inhibition of proliferation of melanoma cells and fibroblasts. Exp Cell Res. 1977 Aug;108(1):119–125. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(77)80017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont S. J., Smyth J. R., Jr Effect of bursectomy on development of a spontaneous postnatal amelanosis. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1981 Dec;21(3):407–411. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(81)90229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner A. B. On the etiology of vitiligo and gray hair. Am J Med. 1971 Aug;51(2):141–147. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(71)90232-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner A. B., Shiohara T., Boissy R. E., Jacobson K. A., Lamoreux M. L., Moellmann G. E. A mouse model for vitiligo. J Invest Dermatol. 1986 Sep;87(3):299–304. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12524353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moellmann G., Klein-Angerer S., Scollay D. A., Nordlund J. J., Lerner A. B. Extracellular granular material and degeneration of keratinocytes in the normally pigmented epidermis of patients with vitiligo. J Invest Dermatol. 1982 Nov;79(5):321–330. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12500086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naughton G. K., Eisinger M., Bystryn J. C. Antibodies to normal human melanocytes in vitiligo. J Exp Med. 1983 Jul 1;158(1):246–251. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.1.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naughton G. K., Mahaffey M., Bystryn J. C. Antibodies to surface antigens of pigmented cells in animals with vitiligo. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1986 Mar;181(3):423–426. doi: 10.3181/00379727-181-42275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordlund J. J., Lerner A. B. Vitiligo. It is important. Arch Dermatol. 1982 Jan;118(1):5–8. doi: 10.1001/archderm.118.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawelek J., Körner A., Bergstrom A., Bologna J. New regulators of melanin biosynthesis and the autodestruction of melanoma cells. Nature. 1980 Aug 7;286(5773):617–619. doi: 10.1038/286617a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rheins L. A., Palkowski M. R., Nordlund J. J. Alterations in cutaneous immune reactivity to dinitrofluorobenzene in graying C57BL/vi.vi mice. J Invest Dermatol. 1986 May;86(5):539–542. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12354989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth J. R., Jr, Boissy R. E., Fite K. V., Albert D. M. Retinal dystrophy associated with a postnatal amelanosis in the chicken. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1981 Jun;20(6):799–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth J. R., Jr, Boissy R. E., Fite K. V. The DAM chicken: a model for spontaneous postnatal cutaneous and ocular amelanosis. J Hered. 1981 May-Jun;72(3):150–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama S. Mode of redifferentiation and melanogenesis of melanocytes in mouse hair follicles. An ultrastructural and cytochemical study. J Ultrastruct Res. 1979 Apr;67(1):40–54. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(79)80016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wick M. M., Byers L., Frei E., 3rd L-dopa: selective toxicity for melanoma cells in vitro. Science. 1977 Jul 29;197(4302):468–469. doi: 10.1126/science.877570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wobmann P. R., Fine B. S. The clump cells of Koganei. A light and electron microscopic study. Am J Ophthalmol. 1972 Jan;73(1):90–101. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(72)90311-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]