Abstract

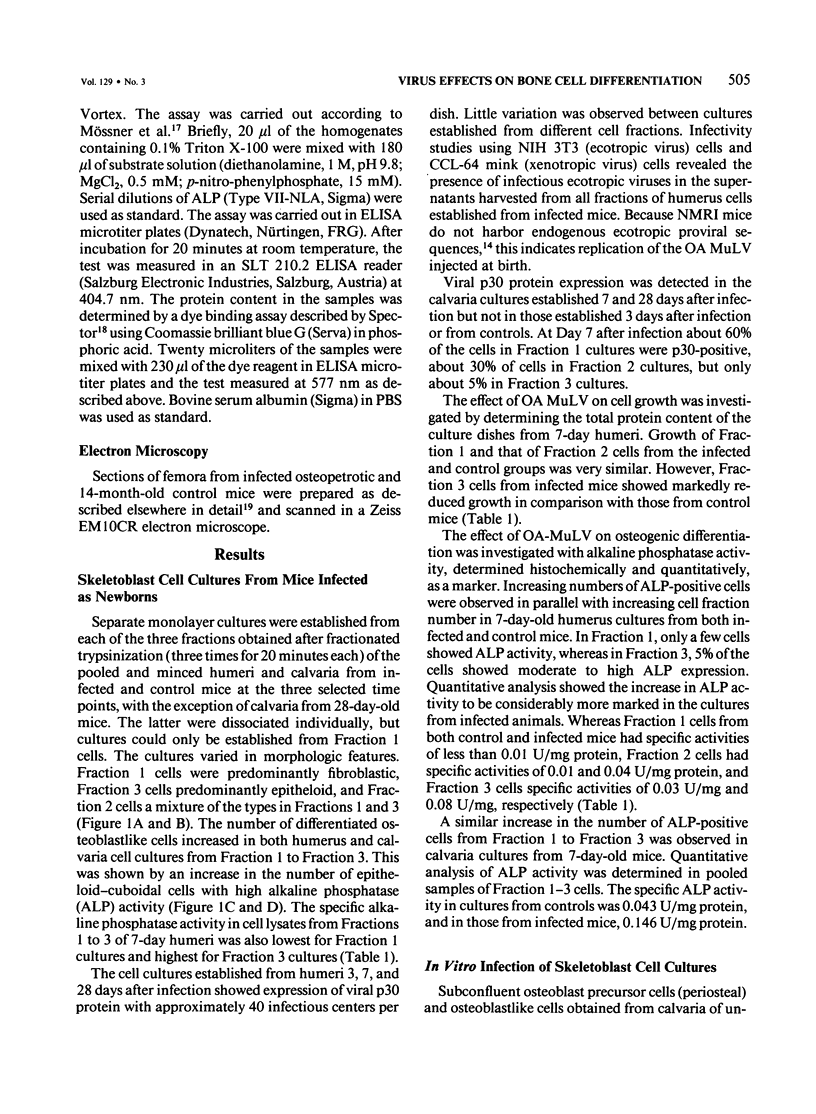

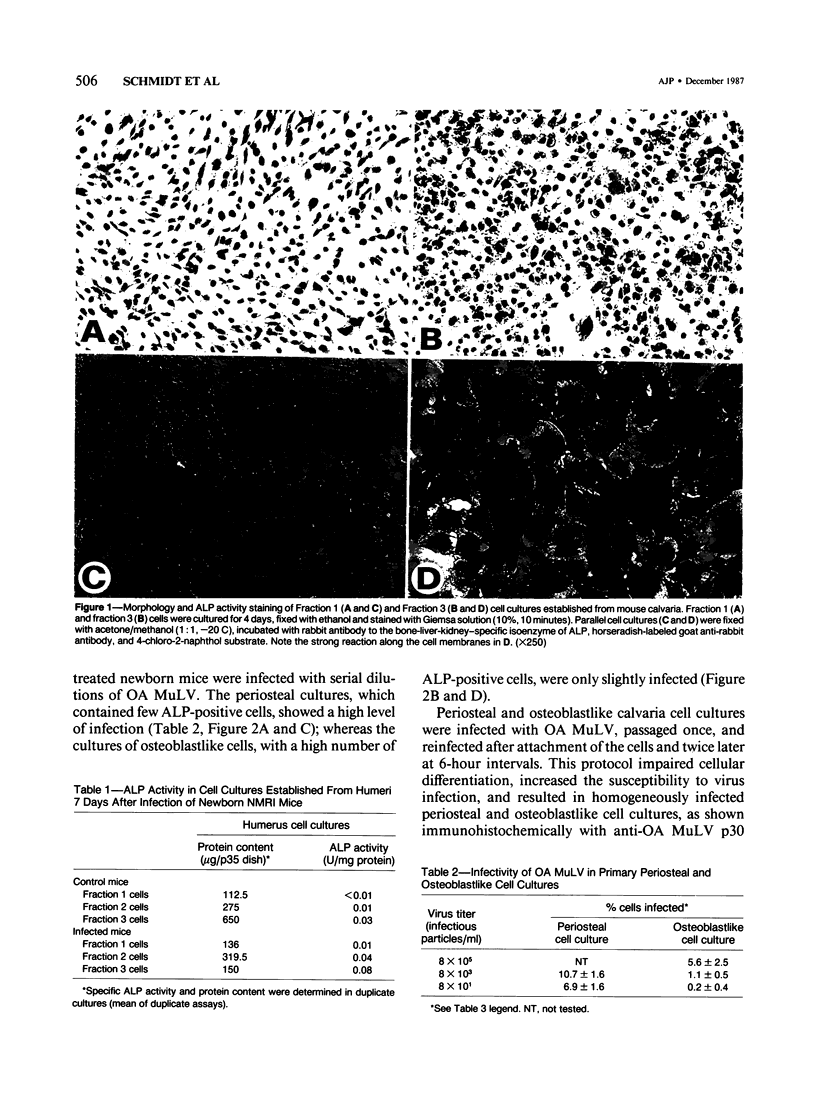

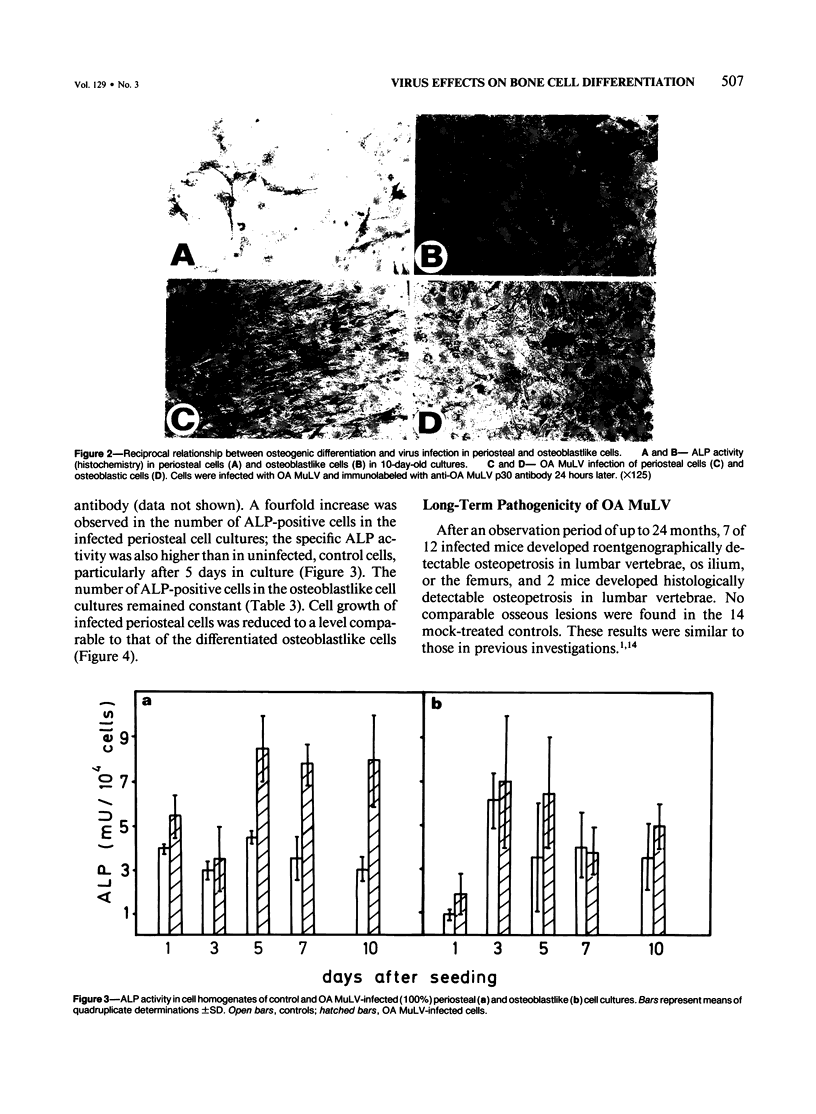

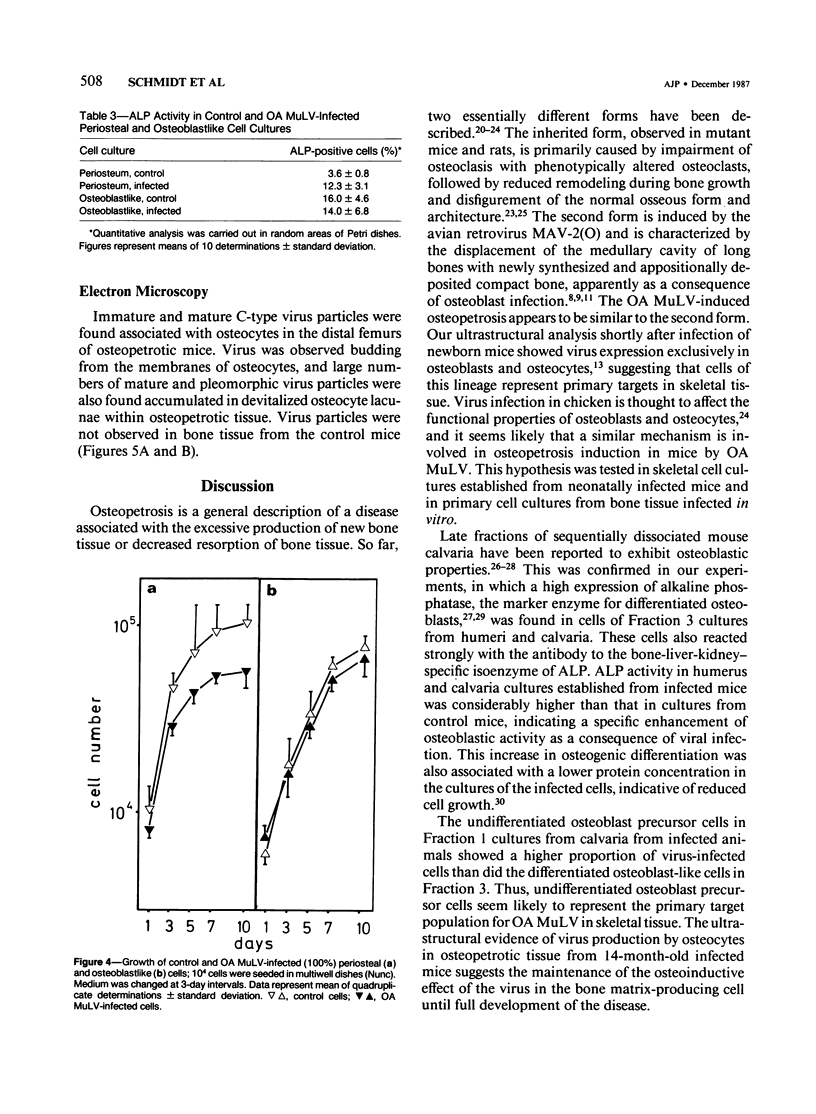

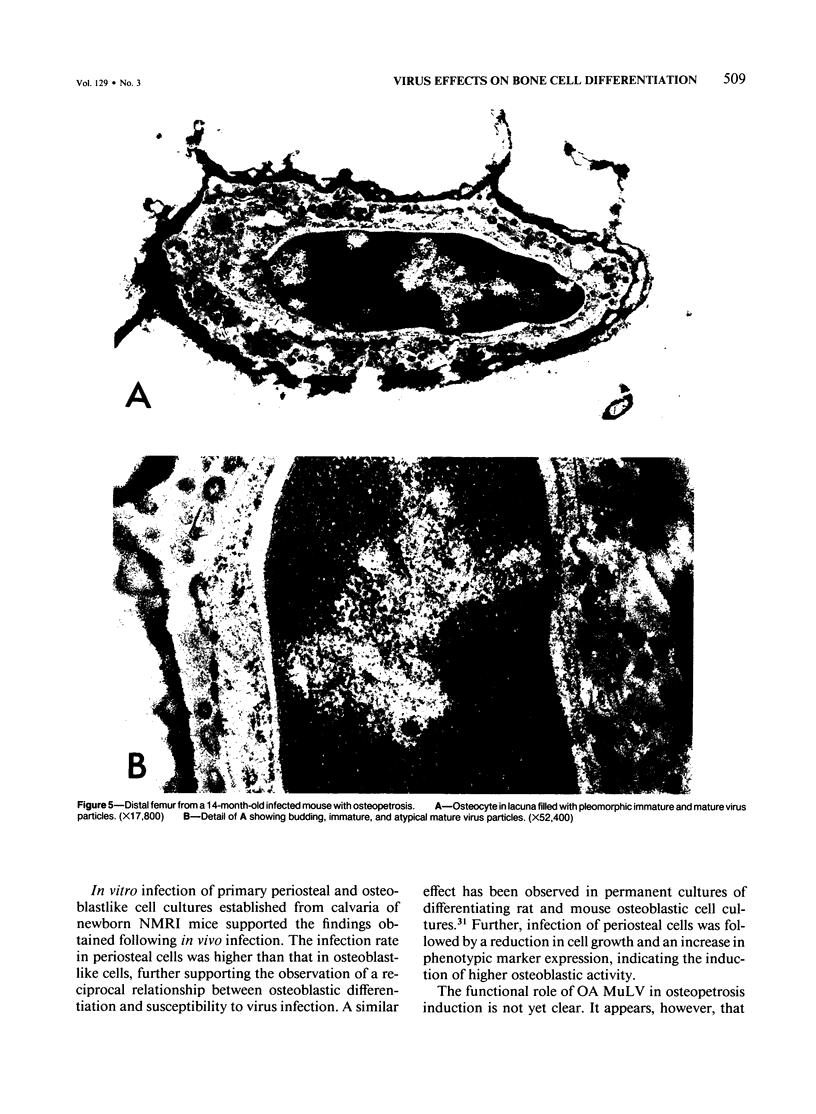

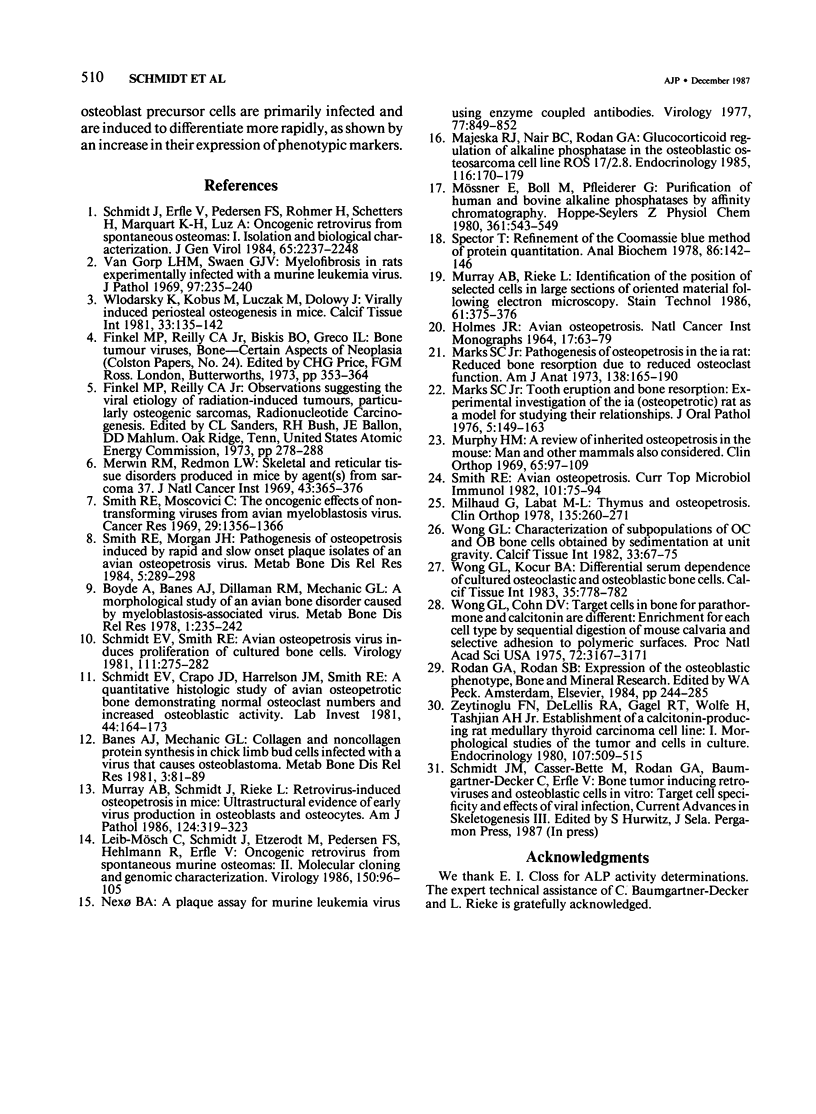

Newborn female strain NMRI mice were injected with a mouse retrovirus (OA MuLV) known to induce osteopetrosis. Primary skeletoblast cell cultures were established from humeri and calvaria of 3-day-old, 7-day-old, and 28-day-old animals. Infectious ecotropic MuLV was found in all humerus cultures from infected animals and in 7-day and 28-day calvaria cell cultures. Levels of alkaline phosphatase activity were markedly higher in cultures of calvaria and humeri from infected mice than in those from controls. In vitro infection of undifferentiated periosteal cells was followed by a decrease in cell growth and an increase in alkaline phosphatase activity. In contrast, differentiated osteoblast-like cells were barely susceptible to OA MuLV infection, and the virus did not influence their cell growth or differentiation. Electron-microscopic studies of skeletal tissue from infected old osteopetrotic mice showed virus particles associated with and budding from osteocytes and accumulated in devitalized osteocyte lacunae. The results indicate that progenitor cells of the osteoblastic lineage represent the target cells for OA MuLV in bone tissue, that virus infection induces an increase in osteoblastic activity, and that infected cells produce virus until full development of the disease.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Banes A. J., Mechanic G. L. Collagen and noncollagen protein synthesis in chick limb bud cells infected with a virus that causes osteoblastoma. Metab Bone Dis Relat Res. 1981;3(2):81–89. doi: 10.1016/0221-8747(81)90025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leib-Mösch C., Schmidt J., Etzerodt M., Pedersen F. S., Hehlmann R., Erfle V. Oncogenic retrovirus from spontaneous murine osteomas. II. Molecular cloning and genomic characterization. Virology. 1986 Apr 15;150(1):96–105. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(86)90269-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majeska R. J., Nair B. C., Rodan G. A. Glucocorticoid regulation of alkaline phosphatase in the osteoblastic osteosarcoma cell line ROS 17/2.8. Endocrinology. 1985 Jan;116(1):170–179. doi: 10.1210/endo-116-1-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks S. C., Jr Pathogenesis of osteopetrosis in the ia rat: reduced bone resorption due to reduced osteoclast function. Am J Anat. 1973 Oct;138(2):165–189. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001380204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks S. C., Jr Tooth eruption and bone resorption: experimental investigation of the ia (osteopetrotic) rat as a model for studying their relationships. J Oral Pathol. 1976 May;5(3):149–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1976.tb01760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merwin R. M., Redmon L. W. Skeletal and reticular tissue disorders produced in mice by agent(s) from Sarcoma 37. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1969 Aug;43(2):365–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milhaud G., Labat M. L. Thymus and osteopetrosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1978 Sep;(135):260–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy H. M. A review of inherited osteopetrosis in the mouse. Man and other mammals also considered. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1969 Jul-Aug;65:97–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray A. B., Rieke L. Identification of the position of selected cells in large sections of oriented material following electron microscopy. Stain Technol. 1986 Nov;61(6):375–376. doi: 10.3109/10520298609113586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray A. B., Schmidt J., Rieke L. Retrovirus-induced osteopetrosis in mice. Ultrastructural evidence of early virus production in osteoblasts and osteocytes. Am J Pathol. 1986 Aug;124(2):319–323. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mössner E., Boll M., Pfleiderer G. Purification of human and bovine alkaline phosphatases by affinity chromatography. Hoppe Seylers Z Physiol Chem. 1980 Apr;361(4):543–549. doi: 10.1515/bchm2.1980.361.1.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nexo B. A. A plaque assay for murine leukemia virus using enzyme-coupled antibodies. Virology. 1977 Apr;77(2):849–852. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(77)90504-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt E. V., Crapo J. D., Harrelson J. M., Smith R. E. A quantitative histologic study of avian osteopetrotic bone demonstrating normal osteoclast numbers and increased osteoblastic activity. Lab Invest. 1981 Feb;44(2):164–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt E. V., Smith R. E. Avian osteopetrosis virus induces proliferation of cultured bone cells. Virology. 1981 May;111(1):275–282. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90672-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt J., Erfle V., Pedersen F. S., Rohmer H., Schetters H., Marquart K. H., Luz A. Oncogenic retrovirus from spontaneous murine osteomas. I. Isolation and biological characterization. J Gen Virol. 1984 Dec;65(Pt 12):2237–2248. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-65-12-2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R. E. Avian osteopetrosis. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1982;101:75–94. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-68654-2_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R. E., Morgan J. H. Pathogenesis of osteopetrosis induced by rapid and slow onset plaque isolates of an avian osteopetrosis virus. Metab Bone Dis Relat Res. 1984;5(6):289–298. doi: 10.1016/0221-8747(84)90016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R. E., Moscovici C. The oncogenic effects of nontransforming viruses from avian myeloblastosis virus. Cancer Res. 1969 Jul;29(7):1356–1366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spector T. Refinement of the coomassie blue method of protein quantitation. A simple and linear spectrophotometric assay for less than or equal to 0.5 to 50 microgram of protein. Anal Biochem. 1978 May;86(1):142–146. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(78)90327-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gorp L. H., Swaen G. J. Myelofibrosis in rats experimentally infected with a murine leukaemia virus. J Pathol. 1969 Feb;97(2):235–240. doi: 10.1002/path.1710970208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong G. L. Characterization of subpopulations of OC and OB bone cells obtained by sedimentation at unit gravity. Calcif Tissue Int. 1982 Jan;34(1):67–75. doi: 10.1007/BF02411211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong G. L., Cohn D. V. Target cells in bone for parathormone and calcitonin are different: enrichment for each cell type by sequential digestion of mouse calvaria and selective adhesion to polymeric surfaces. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975 Aug;72(8):3167–3171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.8.3167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong G. L., Kocour B. A. Differential serum dependence of cultured osteoclastic and osteoblastic bone cells. Calcif Tissue Int. 1983 Sep;35(6):778–782. doi: 10.1007/BF02405123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Włodarski K., Kobus M., Luczak M., Dołowy J. Virally induced periosteal osteogenesis in mice. Calcif Tissue Int. 1981;33(2):135–142. doi: 10.1007/BF02409426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeytinoğlu F. N., DeLellis R. A., Gagel R. F., Wolfe H. J., Tashjian A. H., Jr Establishment of a calcitonin-producing rat medullary thyroid carcinoma cell line. I. Morphological studies of the tumor and cells in culture. Endocrinology. 1980 Aug;107(2):509–515. doi: 10.1210/endo-107-2-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]