Abstract

Apoptosis is an important cellular response to UV radiation (UVR), but the corresponding mechanisms remain largely unknown. Here we report that the p85α regulatory subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI-3K) exerted a proapoptotic role in response to UVR through the induction of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) gene expression. This special effect of p85α was unrelated to the PI-3K-dependent signaling pathway. Further evidence demonstrated that the inducible transcription factor NFAT3 was the major downstream target of p85α for the mediation of UVR-induced apoptosis and TNF-α gene transcription. p85α regulated UVR-induced NFAT3 activation by modulation of its nuclear translocation and DNA binding and the relevant transcriptional activities. Gel shift assays and site-directed mutagenesis allowed the identification of two regions in the TNF-α gene promoter that served as the NFAT3 recognition sequences. Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays further confirmed that the recruitment of NFAT3 to the endogenous TNF-α promoter was regulated by p85α upon UVR exposure. Finally, the knockdown of the NFAT3 level by its specific small interfering RNA decreased UVR-induced TNF-α gene transcription and cell apoptosis. The knockdown of endogenous p85α blocked NFAT activity and TNF-α gene transcription, as well as cell apoptosis. Thus, we demonstrated p85α-associated but PI-3K-independent cell death in response to UVR and identified a novel p85α/NFAT3/TNF-α signaling pathway for the mediation of cellular apoptotic responses under certain stress conditions such as UVR.

Exposure to UV radiation (UVR), a ubiquitous environmental stress factor, is implicated in many medical problems, such as sunburn and skin cancer. Multiple types of damage to the cellular components (DNA, RNA, and proteins) can be observed upon UVR exposure (1, 24, 60). Apoptosis is an important response against oncogenesis by eliminating genetically damaged cells. Thus, the deregulation of the apoptotic response to UV radiation contributes greatly to the process of UVR-induced carcinogenesis (44, 60).

In addition to the direct cellular damage, UVR induces the production and release of some inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (33, 42, 44), interleukin-1 (IL-1) (5), and IL-6 (27). TNF-α induction has been demonstrated to be an acute-phase response to UVR and contributes to UVR-induced cell apoptosis (29, 42, 44). TNF-α was originally established as an important cytokine for the mediation of the immune response, and the corresponding mechanism for the modulation of TNF-α gene expression in the immune system has been well characterized (10, 16, 48, 49). Many of the early studies have demonstrated that the nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) is the key factor responsible for TNF-α induction in T and B lymphocytes exposed to various stimuli (10, 13, 48, 49).

NFAT is a transcription factor family that includes five members: NFAT1 (NFATp or NFATc2), NFAT2 (NFATc or NFATc1), NFAT3 (NFATc4), NFAT4 (NFATc3 or NFATx), and NFAT5 (Ton EBP). Different NFAT members have distinct tissue expression profiles. NFAT1 and NFAT2 are expressed predominantly in the lymphocytes and have been proven to play a pivotal role in human TNF-α gene transcription in response to various types of stimulation (13, 48, 49). NFAT4 is also detected in cells derived from the immune system, and the overexpression of NFAT4 in transgenic mice leads to enhanced TNF-α expression in T cells (7). NFAT5 is distinct from the other four NFAT family members and is involved in the induction of TNF-α gene transcription during hypertonic stress alone (12). Unlike other NFAT family members, NFAT3 is preferentially expressed in the nonlymphoid tissues. Whether this factor plays a regulatory role in TNF-α expression in other somatic cells outside the immune system remains to be elucidated.

Class IA phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI-3K) is a central component for transducing signals essential for multiple cellular processes including cell proliferation, differentiation, motility, and survival. PI-3K is a heterodimer consisting of a 110-kDa catalytic subunit (p110) and a regulatory subunit. To date, five regulatory subunits of PI-3K in mammalian cells have been identified, including two 85-kDa proteins (p85α and p85β), two 55-kDa proteins (p55α and p55γ), and one 50-kDa protein (p50α) (14, 15). Of these isoforms, p85α is predominantly and ubiquitously expressed in most tissues and is thought to be the major element of response to most stimuli (13). One established role for the regulatory subunit of PI-3K is to recruit the p110 catalytic subunit to the membrane and then catalyze the conversion of phosphatidylinositol 4,5,-bisphosphate into the second massager molecule phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphoate, which activates a wide range of the downstream targets, including the serine/threonine kinase Akt (14, 15). Although the PI-3K/Akt signaling pathway mediates cell survival under multiple stress conditions (14, 32), its role in the determination of cell fates in response to UVR appears to be cell type dependent (9, 40, 41, 54, 58).

In addition to forming a complex with the p110 catalytic subunit, p85α exists in a monomeric form due to the greater abundance of p85α than of p110 in many cell types (51). It has been proven that monomeric p85α is able to act as a mediator for transducing the insulin-like growth factor 1-dependent cellular response (33). Moreover, p85α is also involved in the apoptotic response under oxidative stress in a PI-3K-independent manner (57). Therefore, p85α is a multifunctional protein and its role under stress conditions may go beyond its effect through the well-known PI-3K pathway.

Here we addressed a novel function of p85α in UVR response by the genetic abolishment or targeted disruption of p85α expression in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). Our results reveal a p85α-dependent but PI-3K-independent apoptotic response upon UVR and further identify a novel p85α/NFAT3/TNF-α pathway for the specific mediation of type B UV (UVB) radiation-induced cell death. This is the first time, to the best of our knowledge, that the role of p85α in the activation of NFAT3 in response to UVR has been established, and this role may have medical implications in the prevention of UVR-related diseases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids, antibodies, and reagents.

The TNF-α-luciferase reporter plasmid, in which the transcription of the luciferase reporter gene is driven by the upstream 5′-flanking region of the TNF-α gene promoter (nucleotides −1260 to +60), has been described previously (56, 59). The NF-κB-, AP-1-, and NFAT-luciferase reporter plasmids were also described previously (23, 55). The expression plasmid containing full-length mouse p85α cDNA (pSRα-p85α) and the empty vector pSRα were kindly provided by W. Ogawa (Kobe University School of Medicine, Japan) and described previously (19). The plasmids containing cDNA for the dominant negative mutant of PI-3K (Δp85), a deletion mutant of p85α lacking the binding site with the p110 catalytic subunit and thus blocking PI-3K activity, were described in previous studies (19, 30). The adenoviral plasmid expressing the dominant negative mutant of Akt (AD-DN-Akt/K179M), which has a kinase-dead mutation with a single-amino-acid replacement of lysine 179 (K179M), was constructed and kindly provided by Bing-Hua Jiang (West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV). The adenovirus was produced and amplified by transfecting HEK 293 cells with the plasmids. The antibodies used in the Western blot and super gel shift assays were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) and Cell Signal Technology (Beverly, MA), respectively. Cyclosporine A (CsA) and wortmannin were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Cell culture.

p85α+/+ and p85α−/− MEFs isolated from wild-type and p85−/− mice were kindly provided by Y. Terauchi and T. Kadowaki (University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan) and were described in a previous study (47). The TNF-α receptor I (TNF-αRI)−/−, TNF-αRII−/−, TNF-αRI/II−/− MEFs and the corresponding wild-type MEFs were the primary cultures derived from the TNF-αRI, TNF-αRII, and TNF-αRI/II gene knockout mice and the wild-type mice, which were kindly provided by Sung O. Kim (University of Western Ontario, Canada). The MEFs were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 2 mM l-glutamine (Life Technologies, Inc., Rockville, MD).

siRNA.

The small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting the mouse p85α, mouse TNF-α, mouse NFAT3, and human COX-2 genes were designed with the aid of the siRNA Target Finder (http://www.ambion.com/techlib/misc/siRNA_finder.html; Ambion Inc., Austin, TX), and the corresponding expression plasmids were constructed using the GeneSuppressor system (Imgenex Co., San Diego, CA). The target sequence of mouse TNF-α siRNA was 5′-AATTCGAGTGACAAGCCTGTA-3′, the target sequence of human COX-2 siRNA was 5′-AGACAGATCATAAGCGAGGA-3′, and the target sequence of mouse p85α siRNA was 5′-TCGAAGGACTGGAATGTTCGACTCT-3′. The target sequence of mouse NFAT3 siRNA was described previously (31). The siRNA oligonucleotides specifically targeting the mouse TNF-αRI and TNF-αRII genes were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

Cell transfection.

All of the stable and transient transfections were performed with Lipofectamine reagents (Life Technologies, Inc., Rockville, MD) according to the manufacturer's instructions. To stably transfect the p85α+/+ and p85α−/− MEFs with the luciferase reporter constructs, the luciferase reporter plasmids (expressing TNF-α, NF-κB, AP-1, or NFAT) were introduced into the cells together with lacZ-hygro+, a vector conferring hygromycin resistance. The resulting drug-resistant stable transfectants were identified by using hygromycin B selection. For transient transfection, the cells were transfected with the luciferase reporter constructs and then subjected to the next-step exposure 30 h after transfection. To disrupt the expression of p85α, TNF-α, or NFAT3, p85α+/+ MEFs were transfected with the corresponding siRNA recombinant construct and the stable transfectants were identified by using G418 selection. To knock down the expression of TNF-αRI and/or TNF-αRII, the p85α+/+ MEFs were transfected with the commercially available TNF-αRI or TNF-αRII siRNA oligonucleotides either separately or in combination. The cells were then harvested 48 h later and subjected to the next-step stimulations. For the restoration of p85α expression in the p85α−/− MEFs, the cells were cotransfected with the plasmid pSRα-p85α and lacZ-hygro+, and the stable transfectants were obtained by using hygromycin B selection. The wild-type MEFs with Δp85 overexpression were established by cotransfection of the MEFs with the Δp85 construct and the lacZ-hygro+ vector. To interfere with the activity of Akt, the wild-type MEFs were infected with AD-DN-Akt/K179M and the cells were then exposed to UVB radiation 36 h after infection with the virus.

RT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Gibco), and cDNA was synthesized with the ThermoScript reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). For the detection of TNF-α induction, a pair of oligonucleotides (5′-CCAGACCCCACACTCAGAT-3′ and 5′-AACACCCATTCCCTCACAG-3′) were synthesized as described in a previous report (18) and used as the specific primers to amplify mouse TNF-α cDNA. The mouse β-actin cDNA was amplified by using the primers 5′-GACGATGATATTGCCGCACT-3′ and 5′-GATACC ACGCT TGCTCTGAG-3′.

Cell apoptosis assay.

Cells seeded in 6-well plates (2 × 105/well) were starved by replacing the medium with 0.1% FBS-DMEM 24 h prior to UV radiation. Culture plates were then covered with a thin layer of fresh medium (0.1% FBS-DMEM) and exposed to UVR. Control cultures were identically processed but not irradiated. The UVB light source was purchased from UVP Inc. (Upland, CA) and emitted >95% 302-nm-wavelength UVB light. Exposure to UVB radiation for 1, 2, or 4 min corresponds to a dose of 1, 2, or 4 kJ/m2 of UVB radiation. After the indicated time periods, the UVR-treated and control cells were harvested and fixed in 75% ethanol and then stained with propidium iodide solution (50 μg/ml) in the presence of RNase A. Propidium iodide is excluded by the viable cells, but it can penetrate the membranes of the apoptotic or dead cells. The apoptotic profile was determined by flow cytometry utilizing a Beckman-Coulter EpicsXL flow cytometer on the FL3 channel, and gating was set to exclude debris and cellular aggregates. Twenty thousand events were counted for each analysis, and two to four independent experiments for each group were conducted. The subdiploid DNA peak, immediately adjacent to the G0/G1 peak, represented apoptotic cells and was quantified by histogram analyses.

Western blot assay.

Cellular protein extracts were prepared with a cell lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1 mM Na3VO4) and resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The membranes were probed with the primary antibodies indicated in the figures and the alkaline phosphatase-conjugated second antibody. Signals were detected by using the ECF Western blotting system as described in previous reports (24, 30).

Luciferase reporter assay.

MEFs transiently or stably transfected with the luciferase reporter constructs were seeded into 96-well plates (8 × 103/well) and subjected to the various treatments when cultures reached 80 to 90% confluence. Cellular lysates were prepared at the time points indicated in the figures, and the luciferase activities were determined by using a luminometer (Wallac 1420 Victor 2 multilabel counter system) as described in previous studies (24, 30). The results are expressed as relative activities normalized to the luciferase activity in the control cells without treatment.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA).

Nuclear proteins were prepared with the CelLytic-NuCLEAR extraction kit (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) according to the manufacturer's protocols. Five micrograms of nuclear protein was subjected to the gel shift assay by incubation with 1 μg of poly(dI-dC) DNA carrier in DNA binding buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 150 mM KCl, 2 mM EDTA, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1% bovine serum albumin, 20% glycerol) in a final volume of 10 μl on ice for 10 min. Then a volume corresponding to 105 cpm (108 cpm/μg) of the 32P-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotide (2 μl) was added, and the reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min. For competition experiments, 20-fold molar excesses of the unlabeled oligonucleotides or the irrelevant cold probes were added before the addition of the probe. For the super gel shift assay, nuclear extracts were incubated with 2 μg of either the preimmune serum or the specific anti-NFAT3 antibody for 30 min at 4°C before the addition of the probe. DNA-protein complexes were resolved by electrophoresis on 5% nondenaturing glycerol-polyacrylamide gels.

The following synthetic oligonucleotides (5′ to 3′) were used as probes or competitors in EMSA experiments (core sequences are underlined): GCCCAAAGAGGAAAATTTGTTTCATACAG (NFAT site on the murine IL-2 promoter), GGCCCAAAGACCTTTATTTGTTTCATACAG (mutated NFAT site on the murine IL-2 promoter), CCCCAACTTTCCAAACCCT (nucleotides −185 to −167 containing the putative NFAT site on the mouse TNF-α promoter; designated probe TNF-α-NFAT1), GGAAGTTTTCCGAGGGTTGAATGA (nucleotides −79 to −56 containing the putative NFAT site on the mouse TNF-α promoter; designated probe TNF-α-NFAT2), GAACATGTCTTGACATGTTC (p53 site on the mouse p21 promoter), GAGCCGCAAGTGACTCAGCGCGGGCG (AP-1 consensus sequence), and GAGTTGAGGGGACTTTCCCAGGC (NF-κB consensus sequence).

Site-directed mutagenesis.

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed with the QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The following synthetic oligonucleotide primers (lowercase letters indicate the mutated positions) were used for the construction of the mutants: 5′-CTGGGTGTCCCCCAACgTTaaAAACC CTCTGCCCC-3′ (designated −1260 Δ−178) and 5′-CTCCACCAAGGAAGTTagaCGAGGGTTGAATGAGAGC-3′ (designated −1260 Δ−72). The nucleotide sequences of the mutants were confirmed by automatic DNA sequencing.

ChIP assay.

The chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was performed with the EZ ChIP kit (Upstate) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, cells were untreated or treated with UVB radiation (1 kJ/m2) for 12 h and then genomic DNA and the proteins were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde. The cross-linked cells were pelleted, resuspended in lysis buffer, and sonicated to generate 200- to 500-bp chromatin DNA fragments. After centrifugation, the supernatants were diluted 10-fold and then incubated with anti-NFAT3 antibody or the control rabbit immunoglobulin G at 4°C overnight. The immune complex was captured by protein G agarose saturated with salmon sperm DNA and then eluted with the elution buffer. DNA-protein cross-linking was reversed by heating at 65°C for 4 h. DNA was purified and subjected to PCR analysis. To specifically amplify the region containing the putative NFAT-responsive elements on the mouse TNF-α promoter, PCR was performed with the following pair of primers: 5′-CGATGGAGAAGAAACCGAGACAGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-AGGGAGCTTC TGCTGGCTGGCTGT-3′ (reverse). The primers that targeted the region ∼1 kb upstream of the NFAT binding sites on the TNF-α promoter were also used in the PCR analysis to support the specificity of the ChIP assay: 5′-CCTGCACCATCTGTGAAACCCAAT-3′ (forward) and 5′-AATCCACCATGTC TCTGGGAGCTG-3′ (reverse).

RESULTS

Genetic evidence that p85α plays a key role specifically in UVR-induced apoptosis.

p85α has been shown to perform multiple functions dependent on or independent of PI-3K activity (13, 33, 57). To investigate the role of p85α in responses to UVR, primary MEFs isolated from the p85α gene knockout mice and the corresponding wild-type mice with an otherwise identical genetic background were used in the present study.

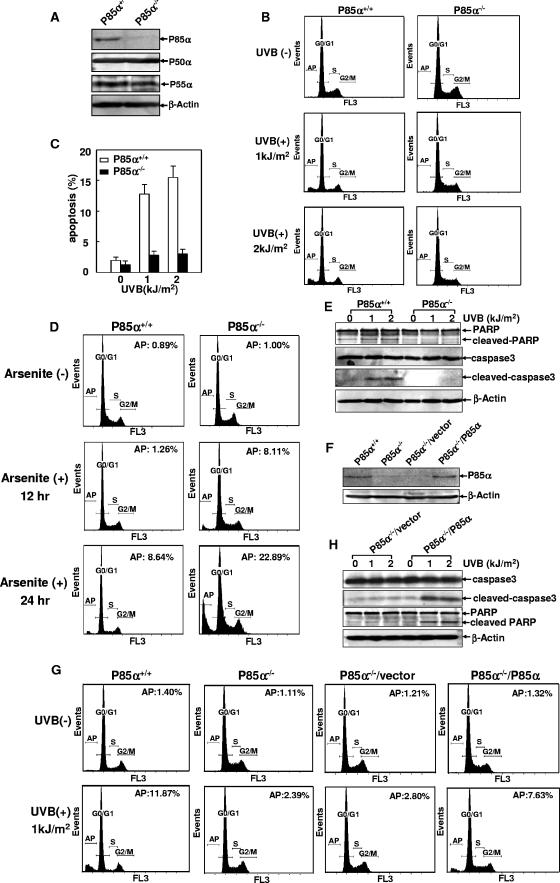

Due to the alternative splicing mechanism, the p85α gene (Pik3r1) encodes three protein isoforms, including the full-length p85α and the two truncated splicing variants, p50α and p55α, which share identical C-terminal sequences with p85α but have the N-terminal section of the p85α polypeptide replaced by unique sequences of 6 and 34 amino acids, respectively (25). The p85α−/− MEFs are derived from the mice with a single deletion of exon 1A (containing the initiation codon for p85α) of the Pik3r1 gene, which results in the selective abolishment of p85α expression without disrupting the p50α and p55α splicing variants corresponding to the intact exons 1B and 1C (containing the initiation codons for p50α and p55α, respectively) (47). We also confirmed the specific absence of p85α expression in p85α−/− MEFs, in which the levels of p50α and p55α were normal, by Western blot assay with the antibody raised against the common C terminus of p85α, p50α, and p55α (Fig. 1A). Another isoform of the 85-kDa regulatory subunit of PI-3K, p85β, was encoded by a distinct sequence of cDNA, and its expression level was not altered by the selective disruption of the p85α gene (47).

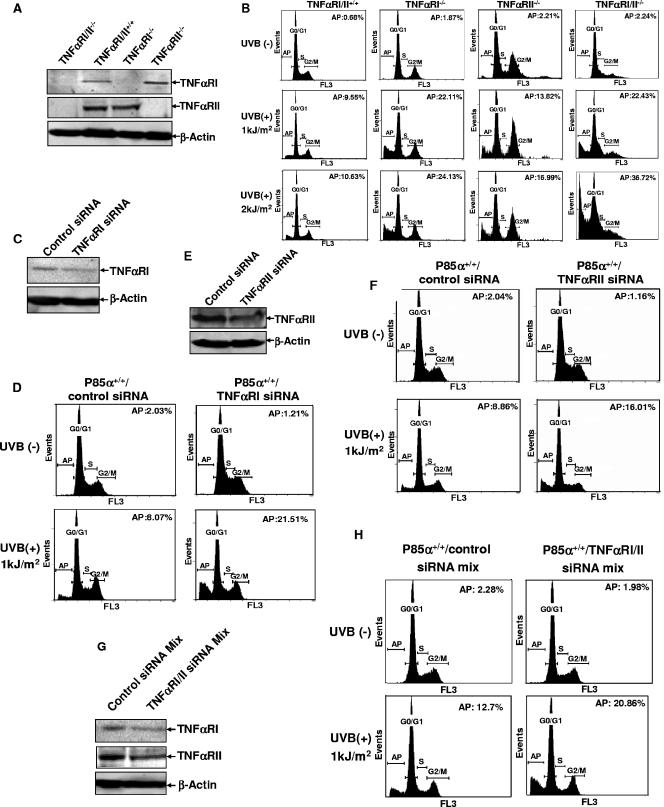

FIG. 1.

p85α exerted proapoptotic activity specifically in response to UVR. (A) Identification of p85α, p50α, and p55α expression in p85α+/+ and p85α−/− MEFs. (B) p85α+/+ and p85α−/− MEFs were exposed to different doses of UVB radiation, and cell apoptosis was determined by flow cytometry analysis 24 h later. AP, apoptosis; +, present; −, absent. (C) Quantification data from three independent experiments described in the legend to panel B. (D) p85α+/+ and p85α−/− MEFs were treated with arsenite (10 μM), and the level of cell apoptosis was determined 12 and 24 h later. Results from a representative experiment and the percentage of the apoptotic cells in each group are presented. (E) p85α+/+ and p85α−/− MEFs were exposed to different doses of UVB radiation, and the cleavage of caspase 3 and PARP was detected 12 h later. (F) Forced expression of p85α partially restored the wild-type response in p85α−/− MEFs (P85α−/−/P85α). (G) p85α+/+ and p85α−/− MEFs, p85α−/− MEFs transfected with a vector, and p85α−/− MEFs expressing p85α were exposed to UVB radiation (2 kJ/m2), and cell apoptosis was detected 24 h later. A representative result and the percentage of the apoptotic cells in each group are presented. (H) p85α−/− MEFs transfected with a vector and p85α−/− MEFs expressing p85α were exposed to different doses of UVB radiation, and the cleavage of caspase 3 and PARP was detected 12 h later.

To determine whether p85α is specifically involved in the stress-induced cellular responses, we initially exposed p85α+/+ and p85α−/− MEFs to various damaging stimuli, including UVR, arsenite, and a nickel compound, and then compared the cellular apoptotic responses of the two types of MEFs. As shown in Fig. 1B and C, apoptosis among the wild-type cells in response to UVR could be obviously detected 24 h after UVR exposure but this response was significantly attenuated among the p85α−/− MEFs under the same conditions. In contrast, the level of induction of apoptosis in response to arsenite was much higher among the p85α−/− MEFs than among the wild-type cells (Fig. 1D), while NiCl2-induced cell death did not show an obvious difference between p85α+/+ and p85α−/− MEFs (data not shown). Therefore, p85α filled a specific role in the mediation of cellular apoptosis in response to UVR. We further confirmed this result by the detection of caspase 3 cleavage and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) cleavage, two well-documented indicators of cell apoptosis (38), which were clearly observed in p85α+/+ MEFs under UV radiation but significantly inhibited in the p85α−/− cells under the same treatment (Fig. 1E). These observations indicate that the incidence of UVR-induced apoptosis was specifically impaired in the p85α-null MEFs.

To rule out the possibility that the resistance to UVR-induced apoptosis in p85α−/− MEFs was due to gene changes other than that resulting in the p85α deficiency during the establishment of the p85α−/− MEFs, p85α−/− MEFs were transfected with a plasmid containing the full-length p85α cDNA for stable expression (Fig. 1F). Compared to the control vector transfectant, p85α−/− MEFs with the forced expression of p85α showed a partially restored apoptotic response under UVR (Fig. 1G). Consistently, UVR-induced caspase 3 and PARP cleavage was also present in the p85α−/− cells in which p85α had been reintroduced (Fig. 1H). These data clearly demonstrate that p85α acts as a mediator specifically for UVR-induced cell apoptosis in MEFs.

The impaired apoptotic response in p85α-null MEFs upon UVR was mediated by a PI-3K-independent pathway.

The PI-3K-dependent pathway has been proven to be a critical cell survival cascade under multiple stress conditions (13, 32), but its role in the response to UVR remains controversial (9, 40, 41, 54, 58). Optimal signaling through PI-3K depends on a critical molecular balance of the regulatory and catalytic subunits (50, 51). Therefore, p85α deficiency might lead to the deregulation of the PI-3K-dependent pathway and affect the cell apoptotic response. To assess this possibility, we detected the activation status of Akt and p70S6k, two important downstream targets of PI-3K that our group has proven to be involved in the response to UVR in another mouse cell line (22, 24, 54). As shown in Fig. 2A, no significant difference in UVR-induced Akt or p70S6k phosphorylation between the p85α-null and the wild-type MEFs was observed. Glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β), a downstream target of Akt in many cellular responses (36), could also be induced by UVB radiation in both p85α+/+ and p85α−/− cells at comparable levels (Fig. 2A). These data suggest that p85α deficiency does not affect the activation status of the PI-3K-dependent pathway in the UVR response.

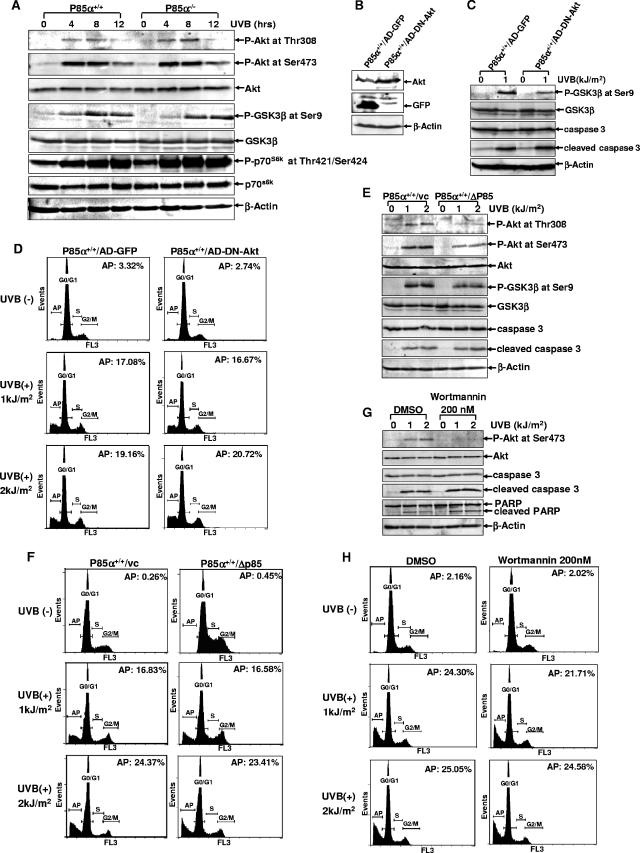

FIG. 2.

The resistance of p85α−/− MEFs to UV-induced apoptosis was unrelated to PI-3K-dependent pathway activation. (A) p85α+/+ and p85α−/− MEFs were exposed to UVB radiation (1 kJ/m2), and the phosphorylation statuses of Akt (P-Akt), GSK3β (P-GSK3β), and p70S6k (P-p70S6k were detected by a Western blot assay at the indicated time periods after UVR exposure. (B) p85α+/+ MEFs were infected with the adenovirus expressing DN-Akt or that expressing GFP (AD-GFP). The overexpression of DN-Akt or GFP in p85α+/+ MEFs was detected 36 h postinfection. (C) Cells described in the legend to panel B were subjected to UVB radiation exposure 36 h after infection with the virus, and the activation of GSK3β and the inducible cleavage of caspase 3 were detected 12 h later. (D) Cells described in the legend to panel B were subjected to UVB radiation exposure, and the incidence of cell death was determined by flow cytometry analysis 30 h after radiation. AP, apoptosis; +, present; −, absent. (E) p85α+/+ MEFs stably transfected with the Δp85 construct or the control vector (vc) were exposed to UVB radiation. The activation of Akt and GSK3β and the inducible cleavage of caspase 3 were detected 12 h later. (F) Cells treated as described in the legend to panel E were subjected to flow cytometry analysis 30 h after UVR exposure to determine the percentage of apoptotic cells. (G) p85α+/+ MEFs were pretreated with wortmannin (200 nM) or its carrier dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) for 1 h, followed by exposure to UV radiation. The activation of Akt and the inducible cleavage of caspase 3 and PARP were detected 12 h later. (H) Cells treated as described in the legend to panel G were subjected to flow cytometry analysis 30 h after UVR exposure.

To further assess the role of the PI-3K-dependent pathway under UVR exposure, AD-DN-Akt/K179M was introduced into the wild-type MEFs and the adenovirus construct expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) was used as a control (Fig. 2B). The effectiveness of the functional overexpression of the dominant negative mutant of Akt (DN-Akt) in p85α+/+ MEFs was confirmed by the reduced activation of the downstream target of Akt, GSK3β, under UVR (Fig. 2C). However, no obvious changes in the incidence of cell death among the DN-Akt-overexpressing p85α+/+ MEFs compared with the GFP-overexpressing cells were observed, as evidenced by both flow cytometric analysis (Fig. 2D) and the induced cleavage of caspase 3 (Fig. 2C). Consistently, the introduction of Δp85 into the wild-type MEFs resulted in an inhibition of UVR-induced Akt and GSK3β activation (Fig. 2E) without influencing the cell apoptotic response to UVR stress (Fig. 2E and F). Similar phenomena in the human keratinocytes have been observed according to a previous report (58). In addition, we found that pretreatment of the wild-type MEFs with wortmannin, an established specific PI-3K inhibitor, had no effects on the cellular apoptotic response to UVR stimulation, although the inducible Akt activation was almost totally blocked by the wortmannin pretreatment (Fig. 2G and H). Taken together, these results indicate that the disruption of PI-3K/Akt pathway activation does not show obvious effects on the incidence of cell death in response to UVR. Accordingly, p85α exerts proapoptotic activity in response to UVR via a PI-3K/Akt-independent pathway.

p85α-null MEFs were competent for the activation of JNKs and p38K in response to UVR.

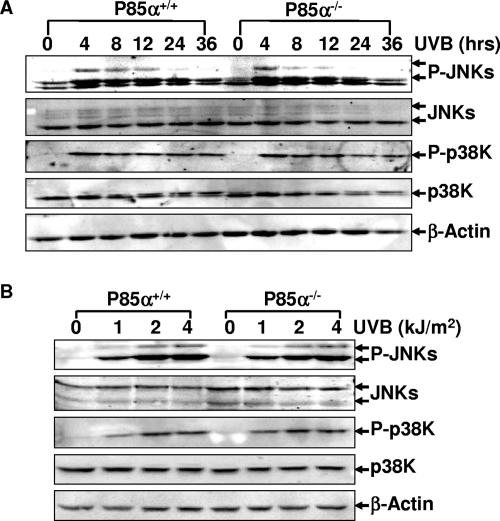

The c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNKs) and p38 kinases (p38K) are two important protein kinases that mediate cell apoptosis induced by various stresses, including UVR (11). To test whether p85α transmits the apoptotic signal through these two pathways, UVR-induced phosphorylation of JNKs and p38K in the wild-type and p85α−/− MEFs was analyzed. As shown in Fig. 3, JNK and p38K phosphorylation under UVR exhibited the same dynamics in both p85α+/+ and p85α−/− MEFs. Thus, we exclude the involvement of JNKs and p38K-dependent pathways in p85α-mediated cell apoptosis in response to UVR.

FIG. 3.

Both p85α+/+ and p85α−/− MEFs are competent for UVB radiation-induced phosphorylation of JNKs (P-JNKs) and p38K (P-p38K). (A) Induction of JNK and p38K phosphorylation at different time periods after a single dose of UVB radiation (1 kJ/m2). (B) Induction of JNK and p38K phosphorylation 1.5 h after treatment with different doses of UVB radiation.

p85α mediated UVR-induced apoptosis by the induction of TNF-α expression.

TNF-α induction is one of the acute-phase responses to UVR and contributes to UVR-induced pathogenic effects, including cell apoptosis (44). To further address the molecular mechanism of p85α-mediated cell death, we next analyzed whether p85α deficiency affected UVR-induced TNF-α expression. To this end, the wild-type and p85α−/− MEFs were stably transfected with the TNF-α-luciferase reporter plasmid, in which the transcription of the luciferase reporter gene was driven by the mouse TNF-α promoter (nucleotides −1260 to +60) (56, 59). We found that the TNF-α promoter-driven luciferase activities were significantly induced in wild-type MEFs in a dose-dependent manner but that such induction was dramatically suppressed in p85α−/− transfectants under the same experimental conditions (Fig. 4A). We further confirmed this result by a RT-PCR assay. Again, the specific transcription of TNF-α mRNA was significantly induced by UVB radiation in wild-type MEFs but not detectable in the p85α−/− MEFs (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that the particular event of TNF-α induction in response to UVR can be interrupted by p85α deficiency.

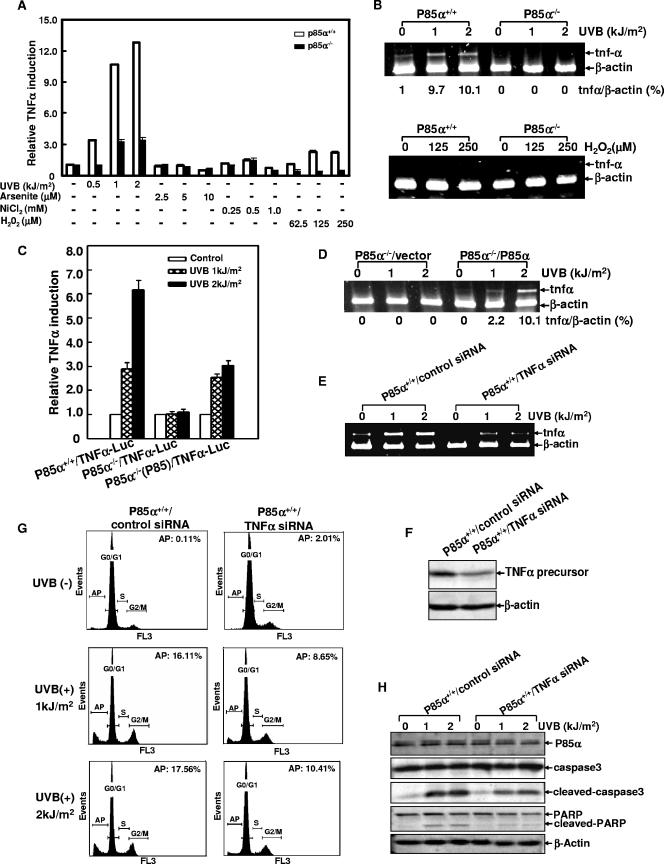

FIG. 4.

p85α-mediated UVB radiation-induced apoptosis by the induction of TNF-α gene transcription. (A) p85α+/+ and p85α−/− MEFs stably transfected with TNF-α-luciferase reporter constructs were exposed to different doses of UVB radiation, arsenite, nickel chloride, or H2O2. The luciferase activities were determined 12 h (for UVB radiation and H2O2) or 24 h (for arsenite and nickel chloride) later. The results were expressed as the relative TNF-α promoter activity normalized to the luciferase activity of the cells without any treatment. (B) p85α+/+ and p85α−/− MEFs were exposed to different doses of UVB radiation (upper panel) or H2O2 (lower panel), and the transcription of TNF-α mRNA was detected by a RT-PCR assay 12 h later. The relative levels of expression of TNF-α mRNA normalized to the expression in the β-actin control are presented. (C and D) The reintroduction of exogenous p85α partially reactivated TNF-α gene transcription in p85α−/− MEFs [P85α−/−(P85)] 24 h after UV radiation. TNFα-Luc, TNF-α-luciferase reporter construct. (E) p85α+/+ MEFs stably transfected with TNF-α-specific siRNA or the control siRNA were exposed to different doses of UVB radiation, and the inducible TNF-α gene transcription was detected by a RT-PCR assay 12 h after UV radiation. (F) Stable transfection with TNF-α-specific siRNA decreased the expression of the TNF-α precursor (30 kDa) in the wild-type cells. (G) Cells described in the legend to panel E were exposed to a single dose of UVB radiation (2 kJ/m2), and the level of cell apoptosis was determined 24 h later. AP, apoptosis; +, present; −, absent. (H) The cleavage of caspase 3 and PARP was inhibited in a stable transfectant with TNF-α siRNA 12 h after UV radiation.

To further illustrate the cause-effect relationship between the expression of p85α and UVR-induced TNF-α gene transcription, the p85α-null MEFs were transfected with the plasmid expressing the full-length p85α and the TNF-α promoter-driven luciferase reporter and then the stable transfectant mass was established. As expected, the reintroduction of p85α into the null mutant cells resulted in the induction of the TNF-α promoter-driven luciferase activities by UVB radiation (Fig. 4C). Consistently, the transcription of TNF-α mRNA induced by UVB radiation was also restored in the MEFs in which p85α was reintroduced, as indicated by the results of the RT-PCR assay (Fig. 4D). We therefore conclude that p85α functions as a mediator for TNF-α induction in fibroblasts in response to UV radiation.

An earlier study revealed that p85α has an effect on the mediation of the apoptotic response to H2O2-induced oxidative stress (57). UV radiation also yields reactive oxidative species in vivo (28). Therefore, we wondered whether p85α-mediated TNF-α up-regulation was a common response to the oxidative stress or whether it was specific to certain UVR damaging signals. To clarify this issue, wild-type and p85α-null MEFs stably transfected with TNF-α-luciferase reporter plasmids were treated with different oxidative reagents, including H2O2, arsenite, and NiCl2 (4, 52). We found that all of these tested oxidative reagents failed to obviously induce the transcriptional activation of the TNF-α promoter (Fig. 4A and B). Therefore, we conclude that the effect of p85α on TNF-α transcriptional activation is specifically induced by UVR damage and is unrelated to the oxidative stress.

To further define whether the p85α-mediated TNF-α induction contributed to UVR-induced cell apoptosis, the wild-type MEFs were stably transfected with a plasmid expressing a specific siRNA targeting the mouse TNF-α gene and a control irrelevant siRNA (human COX-2 siRNA). The efficacy of the stably expressed TNF-α siRNA in the suppression of UVR-induced TNF-α mRNA transcription was verified by a RT-PCR assay (Fig. 4E). Western blot analysis further demonstrated that the stable expression of TNF-α siRNA caused a significant decline in the level of expression of the cellular TNF-α precursor in the whole-cell extracts (Fig. 4F). However, we failed to detect the release of soluble TNF-α into the cell culture supernatant upon UV radiation. Actually, the level of induction of TNF-α proteins by UVB radiation was reported to be extremely low and usually beyond the limit of detection by regular immunoassays (46).We further provided evidence that inhibiting TNF-α induction reduced the incidence of UVR-induced apoptosis (Fig. 4G) and partially inhibited caspase 3 and PARP cleavage in response to UVR (Fig. 4H) while there were no obvious changes in the apoptosis-resistant status of the p85α-null cells with or without TNF-α siRNA transfection (data not shown). These data indicate that the inducible p85α-mediated TNF-α gene transcription represents an apoptotic pathway in response to UVR.

It is generally believed that TNF-α exerts its biological effects by binding with its cognate membrane TNF receptor (17). However, due to the extremely low level of the released TNF-α induced by UVB radiation (as described here and in reference 46), we wondered if this trace amount of TNF-α triggers cellular apoptosis through the classical TNF receptor-dependent manner in response to UVR. To address this issue, primary cultures of TNF-αRI−/−, TNF-αRII−/−, and TNF-αRI/II−/− MEFs (Fig. 5A) were exposed to UVR, and the incidence of cell apoptosis was detected by flow cytometry analysis. Unexpectedly, the knockdown of either membrane TNF-αRI or TNF-αRII or both of the two receptors rendered the cells more sensitive than the wild-type cells, not resistant to, UVR-induced apoptosis under various conditions (Fig. 5B). Consistently, the incidence of cell death in response to UV radiation also increased when the wild-type cells were transfected with TNF-αRI- or TNF-αRII-specific siRNA either separately or in combination compared with that among the control siRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 5C to H). Altogether, these results suggest that TNF-α induced by UVR appears to mediate the prodeath effect independently of the membrane TNF receptor.

FIG. 5.

Knockdown of TNF-α receptor expression increased UVR-induced cell apoptosis. (A) Identification of TNF-αRI−/−, TNF-αRII−/−, and TNF-αRI/II −/− MEFs. (B) TNF-αRI−/−, TNF-αRII−/−, and TNF-αRI/II−/− MEFs and the corresponding wild-type MEFs were exposed to different doses of UVB radiation, and then the level of cell apoptosis was determined 24 h later. AP, apoptosis; +, present; −, absent. (C, E, and G) Wild-type cells were transfected with TNF-αRI- or TNF-αRII-specific siRNAs and the corresponding control siRNAs either separately (C and E) or in combination (G). The levels of expression of TNF-αRI and/or TNF-αRII were detected 48 h after transfection (D, F, and H). Cells described in the legend to panels C, E, and G were subjected to UVB radiation exposure 48 h after transfection, and the level of cell apoptosis was determined 24 h after UV radiation.

NFAT, but not NF-κB, AP-1, or Egr-1, was involved in p85α-mediated TNF-α gene transcription in response to UVR.

Bioinformatics analysis revealed that the mouse TNF-α promoter region was enriched with several putative DNA binding sites of some important transcription factors, such as NF-κB, NFAT, AP-1, and early growth response protein 1 (Egr-1), all of which have been implicated in the regulation of human TNF-α gene expression in the immune-system cells (10, 13, 49, 50). Therefore, to investigate which of these factors is engaged in the p85α-mediated TNF-α induction in response to UVR, the wild-type and p85α-null cells were stably transfected with the luciferase reporter plasmids containing several tandem consensus binding sites for AP-1, NF-κB, or NFAT. The induction of Egr-1 was monitored by Western blot assay. As shown in Fig. 6, UVB radiation-induced NF-κB-dependent luciferase activities were comparable in the wild-type and the p85α-null cells (Fig. 6A). The induction of Egr-1 in response to UVB radiation did not show a big difference in the two types of MEFs, either (Fig. 6B). AP-1 transcriptional activity, as well as the activation of AP-1 components (including Jun, Fos, and ATF family members), was effectively induced by UVB radiation at similar levels in p85α+/+ and p85α−/− MEFs (Fig. 6C and D). Therefore, we exclude the involvement of NF-κB, Egr-1, and AP-1 in the discrepancy in levels of TNF-α induction between the wild-type and the gene knockout cells.

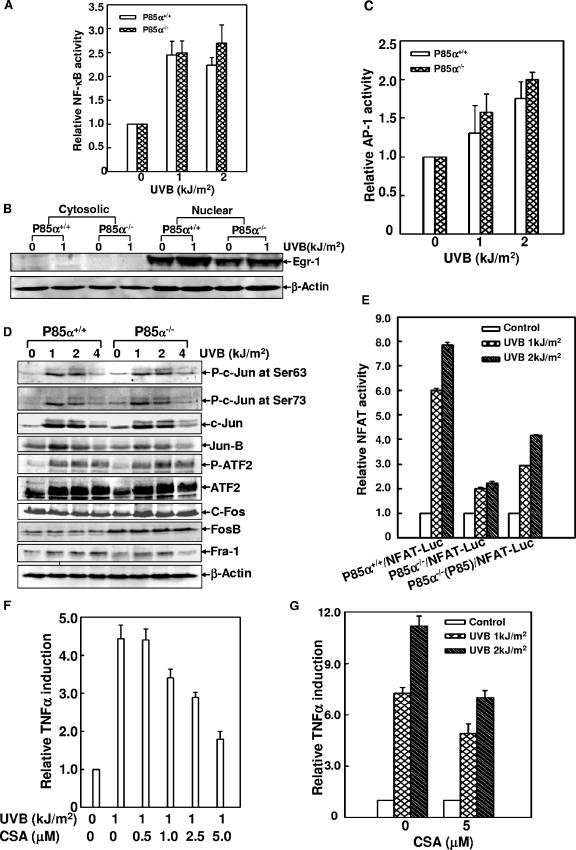

FIG. 6.

NFAT was involved in p85α-mediated TNF-α induction in response to UVR. (A) p85α+/+ and p85α−/− MEFs stably transfected with NF-κB-luciferase reporter constructs were exposed to UV radiation, and the inducible luciferase activities were determined 12 h later. (B) p85α+/+ and p85α−/− MEFs were exposed to UVR (1 kJ/m2), and the cytosolic and nuclear extracts were prepared 12 h after radiation. The expression level of Egr-1 was monitored by a Western blot assay. (C) AP-1 transcriptional activity was determined to be similar to that of NF-κB as described in the legend to panel A. (D) A Western blot assay showed comparable levels of phosphorylation of Jun (P-c-Jun), Fos, and ATF (P-ATF2) family members in response to UVR in p85α+/+ and p85α−/− MEFs. (E) p85α+/+ and p85α−/− MEFs and the p85α−/− MEFs expressing p85α [P85α−/−(P85)] were transiently transfected with the NFAT-luciferase reporter constructs (NFAT-Luc) and exposed to UVB radiation, and the NFAT transcriptional activity was determined 24 h later. (F) p85α+/+ MEFs stably transfected with TNF-α-luciferase reporter constructs were pretreated with different doses of CsA for 2 h and then exposed to UV radiation (1 kJ/m2). The luciferase activities were determined 12 h later. (G) Cells described in the legend to panel F were pretreated with a single dose of CsA (5 μM) for 2 h and then exposed to different doses of UV radiation. The luciferase activities were determined 24 h later.

Some NFAT family members (NFAT4 and 5) have been previously shown to be involved in murine TNF-α induction in T cells (2, 7). One of our previous studies has also demonstrated UV-induced NFAT transactivation in mouse epidermal cells (21). Consistently, we found an obvious induction of NFAT transcriptional activity in the wild-type MEFs upon UV radiation, while a much lower level of induction in p85α−/− cells was observed. The reintroduction of p85α into the null mutant cells partially restored the NFAT transactivation under the same conditions (Fig. 6E). In addition, when the TNF-α-luciferase reporter-transfected wild-type cells were exposed to UV radiation in the presence of different doses of CsA, a specific inhibitor of the calcineurin/NFAT pathway, UVR-induced TNF-α gene transcription was efficiently inhibited in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6F and G). Based on these results, we anticipated that the NFAT activity might be involved in the process of p85α-mediated TNF-α induction in MEFs upon UV radiation.

The process of UVR-induced NFAT3 nuclear translocation and the subsequent binding of NFAT3 to the TNF-α promoter were regulated by p85α in MEFs.

To address which NFAT family member might be involved in p85α-regulated TNF-α gene transcription in response to UVR, whole-cell extracts of p85α+/+ MEFs, p85α−/− MEFs, and the null mutant cells in which p85α expression was restored were subjected to the Western blot assay to detect the expression profiles of the distinct NFAT family members. As shown in Fig. 7A, NFAT3 is the predominant form of this family of proteins expressed in the wild-type MEFs. The deficiency of p85α led to a reduced NFAT3 basal level, and the return of p85α into the null mutant cells restored NFAT3 expression. Although the expression of NFAT4 also could be detected in both the wild-type and the null mutant cells, its role in the p85α-regulated response appeared to be minimal because its level of expression was much lower than that of NFAT3. There was no detectable expression of NFAT1, 2, or 5 in the MEFs. These data suggest that NFAT3 may be the major NFAT family member that is involved in the p85α-regulated response to UVR.

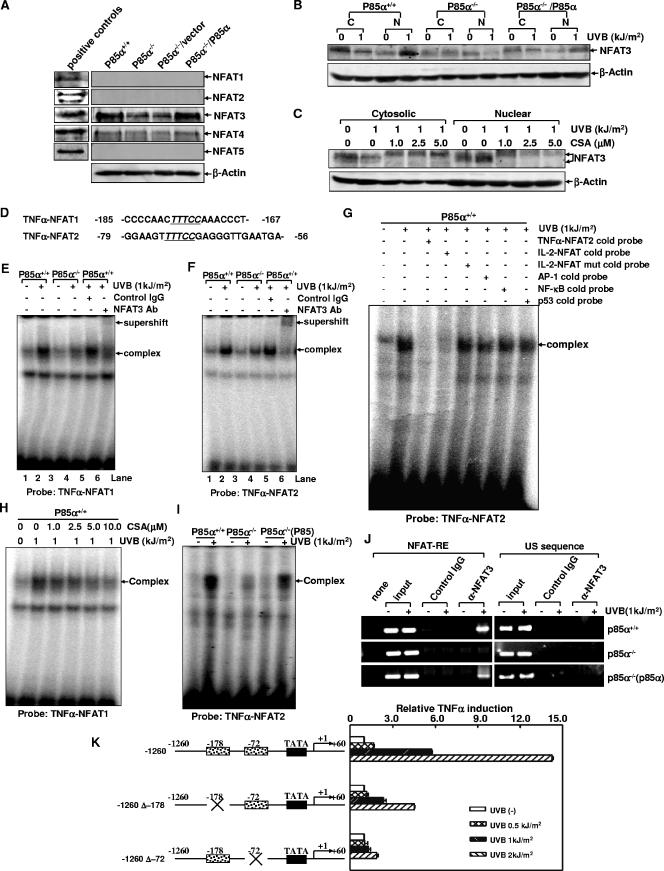

FIG. 7.

NFAT3 nuclear translocation and the DNA binding ability of NFAT3 with the mouse TNF-α gene promoter were regulated by p85α under UVR. (A) The expression profiles of the five NFAT family members in p85α+/+ and p85α−/− MEFs and the null mutant cells in which p85α was reintroduced were determined by a Western blot assay. Commercially available HeLa whole-cell extracts (for NFAT5) or Ramos nuclear extracts (for NFAT1 through 4) served as the positive controls for each antibody. (B) Cytosolic and nuclear extracts (indicated as C and N, respectively) from UVR-treated and untreated p85α+/+ and p85α−/− MEFs and the p85α−/− MEFs expressing p85α were prepared and subjected to a Western blot assay to detect the nuclear translocation of NFAT3 under UV radiation. (C) p85α+/+ MEFs were pretreated with different doses of CsA for 2 h, followed by exposure to UV radiation. The cytosolic or nuclear distribution of NFAT3 was determined 12 h after radiation. (D) Sequences containing two putative NFAT binding sites on the TNF-α gene promoter were used as probes in EMSA experiments. The consensus NFAT binding sequence is underlined and italicized. (E and F) p85α+/+ and p85α−/− MEFs were exposed to UVR (1 kJ/m2). The nuclear extracts prepared 12 h after radiation were subjected to the gel shift assay with TNF-α-NFAT1 (E) or TNF-α-NFAT2 (F) as a probe. A super gel shift assay was performed in the presence of the antibody (Ab) specific for NFAT3 or the preimmune serum. IgG, immunoglobulin G; +, present; −, absent. (G) A 20-fold molar excess of the unlabeled TNF-α-NFAT2, IL-2/NFAT, mutant IL-2/NFAT, NF-κB, p53, or AP-1 cold probe was added to the binding reaction mixtures of p85α+/+ MEFs to determine the specific binding. (H) p85α+/+ MEFs were pretreated with different doses of CsA for 2 h, followed by exposure to UV radiation. Nuclear extracts were prepared 12 h after radiation and subjected to a gel shift assay with the TNF-α-NFAT1 oligonucleotide as a probe. (I) p85α+/+ and p85α−/− MEFs and MEFs with p85α reintroduced [P85α−/−(P85)] were exposed to UVB radiation, and the ability of NFAT to bind to the TNF-α gene promoter was determined 12 h later by using the TNF-α-NFAT2 oligonucleotide as a probe. (J) Soluble chromatin prepared from UVB radiation-treated and -untreated p85α+/+ and p85α−/− MEFs and the p85α−/− MEFs expressing p85α was subjected to a ChIP assay using normal serum or anti-NFAT3 antibody. Immunoprecipitated chromatin DNA was PCR amplified with primers that specifically annealed to the region flanking NFAT-responsive elements (indicated as NFAT-RE) or the sequence ∼1 kb upstream of the NFAT binding sites (indicated as the US sequence) on the TNF-α gene promoter. (K) p85α+/+ MEFs were stably transfected with the parental TNF-α-luciferase reporter construct (−1260) or the individual site-directed mutants (−1260 Δ−178 and −1260 Δ−72). The stable transfectants were treated with different doses of UVB radiation, and the luciferase activities were determined 24 h after radiation.

To reveal how p85α regulates NFAT3 activation in response to UVR, we next detected the nuclear translocation of NFAT3, one of the key steps for the activation of this transcription factor. As shown in Fig. 7B, UV radiation induced an obvious nuclear import of NFAT3 in the wild-type MEFs. However, the process of NFAT3 nuclear accumulation was significantly inhibited in the p85α-null cells. Actually, we repeatedly observed that the amount of nuclear NFAT3 was further decreased, rather than increased, in the null mutant cells after UV radiation. The reintroduction of p85α into the null mutant cells restored the shuttling of NFAT3 into the nucleus upon UVR. In addition, CsA pretreatment significantly blocked the nuclear import of NFAT3 in the wild-type cells in a dose-dependent manner. NFAT3 in CsA-treated cells showed a higher molecular weight than that in the CsA-untreated cells, probably due to the full phosphorylation of this transcription factor through the disruption of the activity of calcineurin in the presence of CsA (Fig. 7C). Taken together, these data indicate that the process of NFAT3 nuclear translocation was regulated by p85α in response to UVR.

To further assess the link between NFAT3 activation and p85α-mediated TNF-α induction under UVR, EMSA experiments were performed to address whether the two putative NFAT binding sites, which contained the GGAAA NFAT core sequence and were located at positions −178 and −72 relative to the transcription start site of the TNF-α gene (Fig. 7D), could act as the functional NFAT-responsive elements in the response to UVR. For this purpose, two oligonucleotides including these sequences were synthesized and used as probes (named TNF-α-NFAT1 and TNF-α-NFAT2) in a gel shift assay. As expected, both of the probes efficiently bound to the nuclear proteins from the UVB radiation-treated p85α+/+ MEFs (lanes 2 in Fig. 7E and F) but the formation of the retarded DNA-protein complexes was significantly inhibited in p85α−/− MEFs (lanes 4 in Fig. 7E and F). The specific binding of the nuclear proteins with these two probes was confirmed by competition experiments. As shown in Fig. 7G, the major retarded band detected by the TNF-α-NFAT2 probe in wild-type cells was efficiently outcompeted by a 20-fold molar excess of the unlabeled TNF-α-NFAT2 cold probe and the oligonucleotide containing the NFAT binding sequence on the murine IL-2 promoter but not by the same amount of the mutant IL-2/NFAT, NF-κB, AP-1, and p53 cold probes. Similar results were also obtained in the TNF-α-NFAT1 cold probe competition assay (data not shown). When the nuclear proteins of UVR-treated wild-type cells were subjected to the super gel shift assay, we found that the addition of the specific anti-NFAT3 antibody to the reaction mixtures caused the supershift of the inducible complexes generated with both probes (lanes 6 in Fig. 7E and F) while the isotype control antibody did not alter the retarded complexes in the samples (lanes 5 in Fig. 7E and F), demonstrating the presence of NFAT3 in both DNA-protein complexes. In addition, CsA pretreatment efficiently inhibited the formation of the specific complexes in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 7H and data not shown). The reintroduction of p85α significantly restored the binding of the nuclear extracts with the two probes in p85α-null cells (Fig. 7I and data not shown). These data indicate that the interaction of the CsA-sensitive NFAT3 with the TNF-α gene promoter was regulated by p85α under UVR.

To further confirm the results from EMSA experiments, we next performed the ChIP assay by using the specific antibody against NFAT3 or normal serum. The detection of the TNF-α promoter among the antibody-captured genomic DNA fragments was performed by PCR amplification with primers designed to specifically recognize the region containing NFAT-responsive elements. As shown in Fig. 7J, efficient promoter amplification from the input samples from p85α+/+ and p85α−/− MEFs and the null mutant cells expressing p85α could be observed, with or without UV radiation. The NFAT3 antibody strongly coimmunoprecipitated with the target TNF-α promoter region DNA from UVB radiation-treated p85α+/+ cells but not with that from the UVB radiation-untreated samples, indicating the inducible recruitment of NFAT3 to the endogenous TNF-α promoter in the wild-type MEFs under the simulated conditions. Furthermore, no signal was observed in the control immunoglobulin G-immunoprecipitated samples, supporting the specific binding of NFAT3 with the TNF-α promoter. In contrast, samples from UVB radiation-treated p85α−/− cells immunoprecipitated with anti-NFAT3 antibody did not show detectable amplification of TNF-α promoter DNA while the immunoprecipitation of the chromatin from UVB radiation-simulated null mutant cells expressing p85α with anti-NFAT3 antibody led to a marked restoration of the enrichment with the target promoter DNA. Further specificity of this ChIP assay was demonstrated by the inability to detect the occupancy of NFAT3 on a region ∼1 kb upstream of the NFAT-responsive elements on the TNF-α promoter. Thus, these results strongly demonstrate the p85α-dependent recruitment of NFAT3 onto the endogenous TNF-α promoter after UVB radiation in vivo.

Given the efficient association of the functional NFAT3 with the TNF-α gene promoter region, we next determined the contribution of these NFAT3 binding sites to the overall transcriptional induction of TNF-α by UVB radiation. To this end, site-directed mutagenesis was performed using the parental TNF-α-luciferase reporter construct (nucleotides −1260 to +60) as a template. As shown in Fig. 7K, mutation of either of the two NFAT binding sites caused a 75 to 90% reduction in the induction of TNF-α gene transcription by UVB radiation, strongly confirming the critical role of NFAT3 in TNF-α induction under UVR.

Knockdown of NFAT3 decreased TNF-α gene transcription and cell apoptosis in response to UVR.

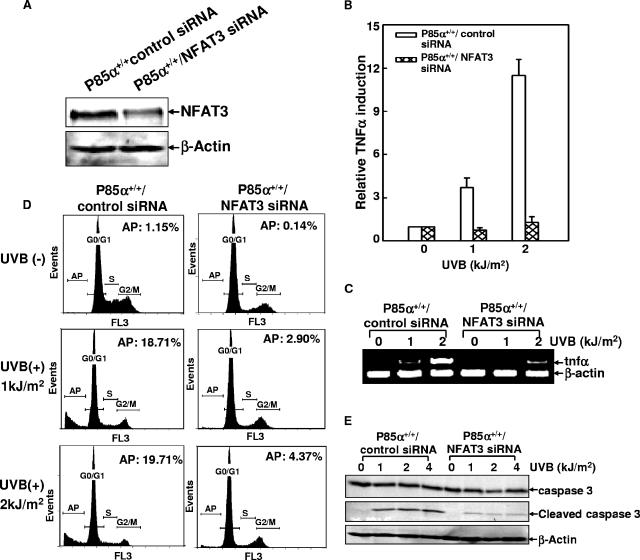

To further confirm the contribution of NFAT3 activation to p85α-mediated TNF-α induction and cell apoptosis, wild-type MEFs were cotransfected with the specific NFAT3 siRNA and the TNF-α-luciferase reporter constructs. The knockdown of NFAT3 expression in the NFAT3 siRNA stable transfectants compared with the expression in control siRNA-transfected cells was verified by a Western blot assay (Fig. 8A). When the cells were exposed to UV radiation, TNF-α promoter-driven luciferase activities were almost abolished by the disruption of NFAT3 expression (Fig. 8B). RT-PCR analysis further confirmed the inhibitory effect of NFAT3 siRNA on UV-induced TNF-α gene transcription (Fig. 8C). Accordingly, cell apoptosis in response to UV radiation was also significantly reduced in NFAT3 siRNA-transfected cells, as evidenced by both flow cytometry and the inducible cleavage of caspase 3 (Fig. 8D and E). These data further demonstrate that NFAT3 is the critical mediator of UVB radiation-induced TNF-α gene transcription and cell apoptosis.

FIG. 8.

Knockdown of NFAT3 expression reduced UVB radiation-induced TNF-α gene transcription and cell apoptosis. (A) p85α+/+ MEFs were cotransfected with NFAT3 siRNA or the control siRNA and the TNF-α-luciferase reporter constructs, and the corresponding stable transfectants were identified. The inhibition of endogenous NFAT3 expression by NFAT3 siRNA transfection was confirmed by Western blot assay. (B and C) Cells described in the legend to panel A were exposed to UVB radiation, and the inducible transcription of the TNF-α gene was assessed by using a luciferase reporter assay (B) and RT-PCR analysis (C). (D) Cells described in the legend to panel A were exposed to UVB radiation, and cell apoptosis was detected 30 h after radiation. AP, apoptosis; +, present; −, absent. (E) Cells described in the legend to panel A were exposed to UVB radiation, and the inducible cleavage of caspase 3 was detected 24 h after UVR exposure.

p85α siRNA blocked UVR-induced apoptosis by the inhibition of NFAT3 activity and TNF-α gene transcription.

To further confirm the above-described results obtained with p85α−/− MEFs, p85α+/+ MEFs were transfected with a construct containing the specific p85α siRNA, and the specific interference in p85α expression in the siRNA stable transfectant, in which the levels of p50α and p55α were normal, was confirmed by a Western blot assay (Fig. 9A). When the cells were subjected to UVR exposure, a significant reduction in the incidence of cell death among the p85α siRNA-transfected MEFs compared with that among the control siRNA-transfected cells was observed (Fig. 9B). Furthermore, the ability of NFAT to bind to the corresponding TNF-α promoter region (Fig. 9C), as well as the inducible TNF-α gene transcription under UVR (Fig. 9D and E), were also obviously inhibited by the specific knockdown of p85α expression. These results further confirm that UVR-induced cell apoptosis is mediated by the p85α/NFAT3/TNF-α signaling pathway.

FIG. 9.

p85α siRNA blocked UVR-induced apoptosis, the DNA binding activity of NFAT, and TNF-α gene transcription. (A) The level of p85α expression was specifically knocked down by transfection with p85α siRNA, while the levels of p50α and p55α were not altered. (B) p85α+/+ MEFs stably transfected with p85α siRNA and the control siRNA were exposed to UVB radiation, and then cell apoptosis was detected 30 h after radiation. AP, apoptosis; +, present; −, absent. (C) Cells described in the legend to panel B were treated with UVB radiation, and the nuclear extracts were prepared 12 h after UVR exposure and then subjected to the gel shift assay using the TNF-α-NFAT2 oligonucleotide as a probe. (D) Cells described in the legend to panel B were transiently transfected with the TNF-α-luciferase reporter construct and then exposed to UV radiation 30 h after transfection. Inducible TNF-α gene transcription was detected 12 h after UVR exposure. (E) The transcription of TNF-α mRNA was detected in the cells described in the legend to panel B by a RT-PCR assay 12 h after UV radiation.

DISCUSSION

UV radiation is an important environmental stress responsible for the occurrence of human skin cancer. Dysfunction of the apoptotic response to UVR plays a critical role in the process of UVR-induced cellular carcinogenesis (1, 24, 60). However, the molecular mechanism for the mediation of the UVR-induced apoptotic effect remains elusive. In this study, we presented evidence that p85α, which is well known as a regulatory subunit of PI-3K, transmits the UVR-induced apoptotic response through the sequential activation of NFAT3 and the induction of TNF-α gene transcription in mouse fibroblasts. Moreover, this proapoptotic role of p85α does not involve PI-3K activity. Thus, our results disclose a novel pathway of p85α/NFAT3/TNF-α for the mediation of cell apoptosis in response to UVR and may have an implication for the prevention of UVR-induced carcinogenesis.

It has been demonstrated that p85α is a multifunctional protein and serves as a critical mediator in various physiological processes, dependent on or independent of PI-3K activity (33, 43, 45, 51, 57). One previous study has revealed the involvement of p85α in the p53-mediated apoptotic response to oxidative stress, which is unrelated to the activation of the PI-3K signal transduction pathway, suggesting the potential role of p85α in transmitting cell damage signaling (57). Our data in the present study provide further strong evidence for a p85α-dependent but PI-3K activity-independent cellular death response which is mediated by the induction of TNF-α expression. These results suggest that p85α transmits apoptotic signaling by employing different pathways under different types of stimulation. In addition, we noticed that the genetic abolishment or targeted disruption of p85α expression did not alter the levels of other PI-3K regulatory subunits (p50α, p55α, and p85β) (Fig. 1A and 9A). Therefore, p85α has the unique proapoptotic activity, probably due to its distinct protein structure, which cannot be found in the other isoforms.

Although we identified the novel p85α/NFAT3/TNF-α pathway for the mediation of the UVR-induced apoptotic effect, it is still unknown how this mediation is linked to the UVR damage signaling. A previous study showed that the level of p85α expression was altered in response to oxidative stress (57). However, unlike the investigators in that study, we did not observe the detectable up- or down-regulation of p85α protein levels in response to UVR (Fig. 4H and data not shown). We therefore propose that the model for the p85α-mediated cell death response under oxidative stress may not be applied to the role of p85α in the response to UV radiation, although the oxidative stress is also a common biological effect of UVR damage. Further supporting this notion, our results indicate that p85α did not mediate an apoptotic effect but rather appeared to confer a protective effect on cells exposed to other well-known oxidative reagents such as arsenite and nickel compounds. Thus, the specific proapoptotic role of p85α reported here may be elicited by UV radiation via an event unrelated to those of oxidative stress.

How p85α is functionally linked to NFAT3 in response to UVR remains to be elucidated. We observed an obviously decreased basal level of NFAT3 due to the deficiency of the p85α gene, and the reintroduction of p85α into the null mutant cells restored NFAT3 expression (Fig. 7A). However, NFAT3 mRNA levels in p85α+/+ and p85α−/− MEFs were comparable (data not shown). Therefore, p85α appears to exert some regulatory function for the stability of NFAT3 in the resting fibroblasts through an unknown mechanism. This result was further supported by the decreased NFAT3 level in the p85α siRNA-transfected MEFs (data not shown). Upon UV radiation, nuclear import and export of NFAT3 was observed in p85α+/+ and p85α−/− MEFs, respectively (Fig. 7B), indicating that p85α regulates the activity of NFAT3 by modulation of its cytoplasm-nucleus shuttling in response to UVR. As we know, nuclear import and export are the most important steps for NFAT activation and are tightly regulated by the phosphorylation status. NFAT proteins are phosphorylated and reside in the cytoplasm in resting cells. Upon stimulation, the calcium- and calmodulin-dependent phosphatase calcineurin triggers the dephosphorylation of NFAT by interacting with the N-terminal regulatory domain conserved in NFAT proteins, which then promotes the translocation of these proteins from the cytoplasm to the nucleus (20, 34). Conversely, the nuclear export of NFATs is triggered by some NFAT kinases, which rephosphorylate the activated dephosphorylated NFAT proteins in the nucleus (20, 34). PI-3K impacts many cellular pathways through phosphorylation cascades; among them, GSK3β has been proven to be a common protein kinase that triggers the phosphorylation and nuclear export of all NFAT family members (3). p38K possesses the same function but selectively targets only NFAT1 and NFAT3 (20). Unfortunately, the UVR-induced activation of both GSK3β and p38K showed similar dynamics in p85α+/+ and p85α−/− MEFs (Fig. 2A and Fig. 3). Thus, we disfavor the possibility that the putative effect of p85α on NFAT3 nuclear localization is via a mechanism that is dependent upon these two kinases. Therefore, p85α is most likely to functionally link to NFAT3 by targeting its nuclear import process via the modulation of calcium mobility, interaction between NFAT3 and calcineurin, or the specific phosphatase activity of calcineurin. Furthermore, p85α contains SH2 and SH3 domains, which can mediate the binding of p85α with other functional proteins, including p110 (15). Thus, the mechanism involving the effect of p85α in response to UVR might also occur through the interplay of p85α with other input from diverse signaling pathways, which possibly results in the recruitment of some adaptor molecule(s) to form a complex with p85α and then cooperatively regulate NFAT3 nuclear translocation and activities.

The essential roles of four NFAT family members (NFAT1, 2, 4, and 5) in the induction of the human TNF-α gene have been extensively illustrated by using immune cells exposed to various stimuli (10, 13, 48, 49). However, there are no reports regarding the involvement of NFAT3 in TNF-α transcriptional regulation, probably due to the preferential expression pattern of NFAT3 outside of the immune system (20). Our result is the first demonstration of the critical role of NFAT3 in the inducible TNF-α gene expression in mouse fibroblasts. Besides the widely known cytokine gene expression properties of NFATs, several reports have addressed the participation of NFATs in cell cycle progression, cell apoptosis, and malignant transformation (8, 39, 53). For example, NFAT1 is able to play a proapoptotic role in T lymphocytes and therefore the deregulation of NFAT1 may rescue normal T cells from apoptosis and enable tumor cell survival (8). Conversely, NFAT2 is proven to protect adipocytes from apoptosis in response to growth factor withdrawal, thus taking part in tumor development by sustaining cell survival (39). In addition, both NFAT1 and NFAT5 have been demonstrated to be mediators of integrin-induced carcinoma invasion (26). Our previous results also elucidate the tumor suppressor function of NFAT3 in mouse epithermal cells in response to tetradecanoyl phorbol acetate stimulation (31). Data in this study further present the putative proapoptotic activity of NFAT3 downstream of p85α, which may prevent the accumulation of the mutant or even the fully malignant cells under UV radiation, thus contributing to the suppression of tumorigenesis.

As an acute-phase response to UV radiation, the induction of TNF-α has been proven to be involved in UVR-triggered cell apoptosis (37, 42, 44), but the mechanism involved in the UVR-induced TNF-α expression is largely unknown. The results of the present study provide direct evidence of the essential role of p85α in UVR-induced TNF-α induction. It is notable that UVR-induced TNF-α gene transcription in keratinocytes can also be observed. Both the keratinocytes and fibroblasts are components of the skin tissue and represent the natural UVR-targeted cell types. Coincidentally, an overdose of p85α expression relative to that of p110 is observed in both types of cells (35, 50, 51). Therefore, it seems that the ratio of p85α to p110 is an important determinant for UV-induced TNF-α expression. How TNF-α induction triggers cell apoptosis in response to UVR also needs further elucidation. It seems that the effect of TNF-α on the mediation of cell apoptosis in response to UVR cannot be explained simply by using the classical model, in which TNF-α exerts activity through binding to its cognate membrane receptor (17), because we failed to detect the release of the mature form of TNF-α from UVB radiation-treated MEFs although the transcription of TNF-α mRNA was substantially induced under the same conditions (Fig. 4A and B). In addition, the knockdown of the expression of either TNF-αRI or TNF-αRII or both made the cells more sensitive rather than resistant to UVR-induced cell apoptosis (Fig. 5). Also, we did not find a detectable difference in JNK and NF-κB activation (Fig. 3 and 6A), the common event associated with the activation of the membrane TNF-α receptor by binding with TNF-α (6), between the wild-type and p85α-knockout MEFs during response to UVR. It has also been shown previously that the direct application of soluble TNF-α is not able to induce apoptosis in mouse keratinocytes, a kind of natural UVR target cells constitutively expressing the TNF-α receptor (44). Therefore, whether TNF-α mediates UV-induced cell apoptosis via other pathways independent of binding with its cognate receptor is an interesting question that is under further investigation.

In summary, the present study demonstrates that the signal transducer p85α can be induced to specifically mediate cell apoptosis in response to UV radiation by activating the novel p85α/NFAT3/TNF-α pathway. Therefore, targeting p85α might be medically significant for obviating UVR-induced skin cancers.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yasuo Terauchi and Takashi Kadowaki for kindly providing p85α+/+ and p85α−/− primary MEFs and W. Ogawa for providing expression plasmid containing full-length p85α cDNA. We are grateful for the help of Haobin Chen and Ping Zhang for their technical discussion.

This work was supported in part by grants from NIH NCI (R01 CA094964, R01 CA112557, and R01 CA103180) and NIH NIEHS (R01 ES012451 and ES000260).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 January 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ananthaswamy, H. N., S. M. Loughlin, P. Cox, R. L. Evans, S. E. Ullrich, and M. L. Kripke. 1997. Sunlight and skin cancer: inhibition of p53 mutations in UV-irradiated mouse skin by sunscreens. Nat. Med. 3:510-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baer, M., A. Dillner, R. C. Schwartz, C. Sedon, S. Nedospasov, and P. F. Johnson. 1998. Tumor necrosis factor alpha transcription in macrophages is attenuated by an autocrine factor that preferentially induces NF-κB p50. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:5678-5689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beals, C. R., C. M. Sheridan, C. W. Turck, P. Gardner, and G. R. Crabtree. 1997. Nuclear export of NF-ATc enhanced by glycogen synthase kinase-3. Science 275:1930-1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernstam, L., and J. Nriagu. 2000. Molecular aspects of arsenic stress. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health B 3:293-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanton, R. A., T. S. Kupper, J. K. McDougall, and S. Dower. 1989. Regulation of interleukin 1 and its receptor in human keratinocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:1273-1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bubici, C., S. Papa, C. G. Pham, F. Zazzeroni, and G. Franzoso. 2004. NF-κB and JNK. An intricate affair. Cell Cycle 3:1524-1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, J., Y. Amasaki, Y. Kamogawa, M. Nagoya, N. Arai, K. Arai, and S. Miyatake. 2003. Role of NFATx (NFAT4/NFATc3) in expression of immunoregulatory genes in murine peripheral CD4+ T cells. J. Immunol. 170:3109-3117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chuvpilo, S., E. Jankevics, D. Tyrsin, A. Akimzhanov, D. Moroz, M. K. Jha, J. Schulze-Luehrmann, B. Santner-Nanan, E. Feoktistova, T. Konig, A. Avots, E. Schmitt, F. Berberich-Siebelt, A. Schimpl, and E. Serfling. 2002. Autoregulation of NFATc1/A expression facilitates effector T cells to escape from rapid apoptosis. Immunity 16:881-895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coffer, P. J., B. M. Burgering, M. P. Peppelenbosch, J. L. Bos, and W. Kruijer. 1995. UV activation of receptor tyrosine kinase activity. Oncogene 11:561-569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Decker, E. L., N. Nehmann, E. Kampen, H. Eibel, P. F. Zipfel, and C. Skerka. 2003. Early growth response proteins (EGR) and nuclear factors of activated T cells (NFAT) form heterodimers and regulate proinflammatory cytokine gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 313:911-921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dent, P., A. Yacoub, J. Contessa, R. Caron, G. Amorino, K. Valerie, M. P. Hagan, S. Grant, and R. Schmidt-Ullrich. 2003. Stress and radiation-induced activation of multiple intracellular signaling pathways. Radiat. Res. 159:283-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esensten, J. H., A. V. Tsytsykova, C. Lopez-Rodriguez, F. A. Ligeiro, A. Rao, and A. E. Goldfeld. 2005. NFAT5 binds to the TNF promoter distinctly from NFATp, c, 3 and 4, and activates TNF transcription during hypertonic stress alone. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:3845-3854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falvo, J. V., A. M. Uglialoro, B. M. Brinkman, M. Merika, B. S. Parekh, E. Y. Tsai, H. C. King, A. D. Morielli, E. G. Peralta, T. Maniatis, D. Thanos, and A. E. Goldfeld. 2000. Stimulus-specific assembly of enhancer complexes on the tumor necrosis factor alpha gene promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:2239-2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franke, T. F., C. P. Hornik, L. Segev, G. A. Shostak, and C. Sugimoto. 2003. PI3K/Akt and apoptosis: size matters. Oncogene 22:8983-8998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fruman, D. A., R. E. Meyers, and L. C. Cantley. 1998. Phosphoinositide kinases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67:481-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldfeld, A. E., P. G. McCaffrey, J. L. Strominger, and A. Rao. 1993. Identification of a novel cyclosporin-sensitive element in the human tumor necrosis factor alpha gene promoter. J. Exp. Med. 178:1365-1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta, S. 2002. A decision between life and death during TNF-alpha-induced signaling. J. Clin. Immunol. 22:185-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hadded, E. K., A. J. Duclos, W. S. Lapp, and M. G. Baines. 1997. Early embryo loss is associated with the expression of macrophage activation marker in the Decidua. J. Immunol. 158:4886-4892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hara, K., K. Yonezawa, H. Sakaue, A. Ando, K. Kotani, T. Katimura, Y. Katimura, H. Ueda, L. Stephens, T. R. Jakson, P. T. Hawkins, R. Dhand, A. E. Clark, G. D. Holman, M. D. Waterfield, and M. Kasuga. 1994. 1-Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity is required for insulin-stimulated glucose transport but not for RAS activation in CHO cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:415-419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hogan, P. G., L. Chen, J. Nardone, and A. Rao. 2003. Transcriptional regulation by calcium, calcineurin, and NFAT. Genes Dev. 17:2205-2232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang, C., P. Mattjus, W. Y. Ma, M. Rincon, N. Y. Chen, R. E. Brown, and Z. Dong. 2000. Involvement of nuclear factor of activated T cells activation in UV response. Evidence from cell culture and transgenic mice. J. Biol. Chem. 275:9143-9149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang, C., J. Li, M. Ding, S. S. Leonard, L. Wang, V. Castranova, V. Vallyathan, and X. Shi. 2001. UV induces phosphorylation of protein kinase B (Akt) at Ser-473 and Thr-308 in mouse epidermal Cl 41 cells through hydrogen peroxide. J. Biol. Chem. 276:40234-40240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang, C., J. Li, M. Costa, Z. Zhang, S. S. Leonard, V. Castranova, V. Vallyathan, G. Ju, and X. Shi. 2001. Hydrogen peroxide mediates activation of nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) by nickel subsulfide. Cancer Res. 61:8051-8057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang, C., J. Li, Q. Ke, S. S. Leonard, B. H. Jiang, X. S. Zhong, M. Costa, V. Castranova, and X. Shi. 2002. Ultraviolet-induced phosphorylation of p70(S6K) at Thr(389) and Thr(421)/Ser(424) involves hydrogen peroxide and mammalian target of rapamycin but not Akt and atypical protein kinase C. Cancer Res. 62:5689-5697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inukai, K., M. Funaki, T. Ogihara, H. Katagiri, A. Kanda, M. Anai, Y. Fukushima, T. Hosaka, M. Suzuki, B. C. Shin, K. Takata, Y. Yazaki, M. Kikuchi, Y. Oka, and T. Asano. 1997. p85alpha gene generates three isoforms of regulatory subunit for phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI 3-Kinase), p50alpha, p55alpha, and p85alpha, with different PI 3-kinase activity elevating responses to insulin. J. Biol. Chem. 272:7873-7882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jauliac, S., C. Lopez-Rodriguez, L. M. Shaw, L. F. Brown, A. Rao, and A. Toker. 2002. The role of NFAT transcription factors in integrin-mediated carcinoma invasion. Nat. Cell Biol. 4:540-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirnbauer, R., A. Kock, P. Neuner, E. Forster, J. Krutmann, A. Urbanski, E. Schauer, J. C. Ansel, T. Schwarz, and T. A. Luger. 1991. Regulation of epidermal cell interleukin 6 production by UV and corticosteroid. J. Investig. Dermatol. 96:484-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kulms, D., and T. Schwarz. 2002. Molecular mechanisms involved in UV-induced apoptotic cell death. Skin Pharmacol. Appl. Skin Physiol. 15:342-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leverkus, M., M. Yaar, M. S. Eller, E. H. Tang, and B. A. Gilchrest. 1998. Post-translational regulation of UV-induced TNF-alpha expression. J. Investig. Dermatol. 110:353-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li, J., G. Davidson, Y. Huang, B. H. Jiang, X. Shi, M. Costa, and C. Huang. 2004. Nickel compounds act through phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/Akt-dependent, p70(S6k)-independent pathway to induce hypoxia inducible factor transactivation and Cap43 expression in mouse epidermal Cl41 cells. Cancer Res. 64:94-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li, J., L. Song, D. Zhang, L. Wei, and C. Huang. 2006. Knockdown of NFAT3 blocked TPA-induced COX-2 and iNOS expression, and enhanced cell transformation in Cl41 cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 99:1010-1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo, J., B. D. Manning, and L. C. Cantley. 2003. Targeting the PI3K-Akt pathway in human cancer: rationale and promise. Cancer Cell 4:257-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luo, J., S. J. Field, J. Y. Lee, J. A. Engelman, and L. C. Cantley. 2005. The p85 regulatory subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase down-regulates IRS-1 signaling via the formation of a sequestration complex. J. Cell Biol. 170:455-464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Macian, F. 2005. NFAT proteins: key regulators of T-cell development and function. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5:472-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mauvais-Jarvis, F., K. Ueki, D. A. Fruman, M. F. Hirshman, K. Sakamoto, L. J. Goodyear, M. Iannacone, D. Accili, L. C. Cantley, and C. R. Kahn. 2002. Reduced expression of the murine p85alpha subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase improves insulin signaling and ameliorates diabetes. J. Clin. Investig. 109:141-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitsiades, C. S., N. Mitsiades, and M. Koutsilieris. 2004. The Akt pathway: molecular targets for anti-cancer drug development. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 4:235-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moore, R. J., D. M. Owens, G. Stamp, C. Arnott, F. Burke, N. East, H. Holdsworth, L. Turner, B. Rollins, M. Pasparakis, G. Kollias, and F. Balkwill. 1999. Mice deficient in tumor necrosis factor-alpha are resistant to skin carcinogenesis. Nat. Med. 5:828-831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mullen, P. 2004. PARP cleavage as a means of accessing apoptosis. Methods Mol. Med. 88:171-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neal, J. W., and N. A. Clipstone. 2003. A constitutively active NFATc1 mutant induces a transformed phenotype in 3T3-L1 fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 278:17246-17254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nomura, M., A. Kaji, Z. He, W.-Y. Ma, K.-I. Miyamoto, C. S. Yang, and Z. Dong. 2001. Inhibitory mechanisms of tea polyphenols on the ultraviolet B-induced phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 276:46624-46631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nomura, M., A. Kaji, W.-Y. Ma, S. Zhong, G. Liu, G. T. Bowden, K.-I. Miyamoto, and Z. Dong. 2001. Mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase 1 mediates activation of Akt by ultraviolet B radiation. J. Biol. Chem. 276:25558-25567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Piguet, P. E., G. E. Grau, C. Hauser, and P. Vassalli. 1991. Tumor necrosis factor is a critical mediator in hapten induced irritant and contact hypersensitivity reactions. J. Exp. Med. 173:673-679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ren, S. Y., E. Bolton, M. G. Mohi, A. Morrione, B. G. Neel, and T. Skorski. 2005. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase p85α subunit-dependent interaction with BCR/ABL-related fusion tyrosine kinases: molecular mechanisms and biological consequences. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:8001-8008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwardz, A., R. Bhardwaj, Y. Aragane, K. Mahnke, H. Riemann, D. Metze, T. A. Luger, and T. Schwardz. 1995. Ultraviolet-B-induced apoptosis of kerotinocytes: evidence for partial involvement of tumor necrosis factor alpha in the formation of sunburn cells. J. Investig. Dermatol. 104:922-927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shekar, S. C., H. Wu, Z. Fu, S. C. Yip, Nagajyothi, S. M. Cahill, M. E. Girvin, and J. M. Backer. 2005. Mechanism of constitutive phosphoinositide 3-kinase activation by oncogenic mutants of the p85 regulatory subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 280:27850-27855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strozyk, E., B. Poppelmann, T. Schwarz, and D. Kulms. 2006. Differential effects of NF-kappaB on apoptosis induced by DNA-damaging agents: the type of DNA damage determines the final outcome. Oncogene 25:6239-6251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Terauchi, Y., Y. Tsuji, S. Satoh, H. Minoura, K. Murakami, A. Okuno, K. Inukai, T. Asano, Y. Kaburagi, K. Ueki, H. Nakajima, T. Hanafusa, Y. Matsuzawa, H. Sekihara, Y. Yin, J. C. Barrett, H. Oda, T. Ishikawa, Y. Akanuma, I. Komuro, M. Suzuki, K. Yamamura, T. Kodama, H. Suzuki, K. Yamamura, T. Kodama, H. Suzuki, S. Koyasu, S. Aizawa, K. Tobe, Y. Fukui, Y. Yazaki, and T. Kadowaki. 1999. Increased insulin sensitivity and hypoglycaemia in mice lacking the p85α subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Nat. Genet. 21:230-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsai, E. Y., J. Jain, P. A. Pesavento, A. Rao, and A. E. Goldfeld. 1996. Tumor necrosis factor alpha gene regulation in activated T cells involves ATF-2/Jun and NFATp. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:459-467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsai, E. Y., J. Yie, D. Thanos, and A. E. Goldfeld. 1996b. Cell-type-specific regulation of the human tumor necrosis factor alpha gene in B cells and T cells by NFATp and ATF-2/JUN. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:5232-5244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ueki, K., C. M. Yballe, S. M. Brachmann, D. Vicent, J. M. Watt, C. R. Kahn, and L. C. Cantley. 2002a. Increased insulin sensitivity in mice lacking p85beta subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:419-424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]