Abstract

Boundary elements have been found in the Abd-B 3′ cis-regulatory region, which is subdivided into a series of iab domains. Previously, a 340-bp insulator-like element, M340, was identified in one such 755-bp Mcp fragment linked to the PcG-dependent silencer. In this study, we identified a 210-bp core that was sufficient for pairing of sequence-remote Mcp elements. In two-gene transgenic constructs with two Mcp insulators (or their cores) surrounding yellow, the upstream yeast GAL4 sites were able to activate the distal white only if the insulators were in the opposite orientations (head-to-head or tail-to-tail), which is consistent with the looping/bypass model. The same was true for the efficiency of the cognate eye enhancer, while yellow thus isolated in the loop from its enhancers was blocked more strongly. These results indicate that the relative placement and orientation of insulator-like elements can determine proper enhancer-promoter communication.

In eukaryotic organisms, precise control of spatially and temporally regulated genes requires a large set of enhancers, which are often located at considerable distances from the regulated gene (4, 6, 15, 19, 20, 21, 39, 66, 72). Most of recent data (13, 54, 69) support the looping model (56), which postulates that enhancers and distant promoters are in physical contact, while the intervening sequences loop out. Accordingly, one of the key questions is how distant enhancers communicate with their target promoters. One of the best model systems for studying long-distance enhancer-promoter communication is the regulatory region of the homeotic Abdominal-B (Abd-B) gene of the bithorax complex (45, 66).

The three homeotic genes of the bithorax complex—Ultrabithorax (Ubx), abdominal-A (abd-A), and Abdominal-B (Abd-B)—are responsible for specifying the identity of parasegment 5 (PS5) to PS14, which form the posterior half of the thorax and all abdominal segments of an adult fly (41, 45, 50, 60). The PS-specific expression patterns of Ubx, abd-A, and Abd-B are determined by a complex cis-regulatory region that spans a 300-kb DNA segment (45, 66). For example, Abd-B expression in PS10, PS11, PS12, and PS13 is controlled by the iab-5, iab-6, iab-7, and iab-8 cis-regulatory domains, respectively (7, 14, 23, 34, 41, 51, 61). Each iab domain appears to contain at least one enhancer that initiates Abd-B expression in the early embryo, as well as a PRE silencer element that maintains the expression pattern throughout development (2, 8, 9, 31, 32, 48, 49, 51, 74, 75). It has been proposed that insulators flank each iab region and organize the Abd-B regulatory DNA into a series of separate chromatin loop domains (25, 30, 50, 51). The recent finding that iab-7 is flanked by two insulators, Fab-7 and Fab-8, is consistent with this model (2, 31, 74).

The third identified boundary element, Mcp, preserves the functional autonomy of the iab-4 and iab-5 cis-regulatory domains (34, 35, 41). It has recently been found that a core 800-bp Mcp sequence from the iab-5 regulatory region of the Abd-B gene can mediate trans regulation between transgenes located at distant sites of the same chromosome arm or even on different arms (52, 71). Previous data suggest that this 800-bp Mcp element functions both as a silencer and as a domain boundary element (35, 50). A silencer in the 138-bp minimal element was mapped owing to its ability to maintain silencing during imaginal disc development (10). Recently a 340-bp regulatory element (designated M340) with an insulator property was identified adjacent to the Mcp silencer (28).

Here, we studied the enhancer-blocking and pairing activities of different parts of the Mcp element. The results show that GAF binding sites located in the adjacent silencer contribute to the enhancer-blocking activity of M340. When the Mcp elements flank the yellow gene, the enhancer-blocking activity is significantly improved, suggesting that the loop formed by the interacting Mcp elements interferes with enhancer-promoter communication. The 210-bp core of M340 functions as a weak insulator but is sufficient for orientation-dependent pairing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid constructions.

Details of transgene construction are available upon request. An 8-kb fragment containing the yellow gene was kindly provided by P. Geyer. The 5-kb BamHI-BglII fragment containing the coding region (yc) was subcloned into CaSpeR2 (C2-yc). The CaSpeR vectors carrying the white gene were kindly provided by V. Pirrotta. The 3-kb SalI-BamHI fragment containing the yellow regulatory region (yr) was subcloned into BamHI-XhoI-cleaved pGEM7 (yr plasmid). The eye enhancer was then inserted into the yr plasmid cleaved by BglII. The pCaSpew15(+RI) plasmid was constructed by inserting an additional EcoRI site at +3,291 bp of the mini-white gene in the pCaSpew15 plasmid. An insulator located at the 3′ side of the mini-white gene (mw insulator) was deleted from pCaSpew15(+RI) by digestion with EcoRI to produce the pCaSpeRΔ700 plasmid. The BamHI-BglII fragment of the yellow coding region was cloned into pCaSpeRΔ700 (C2-yc).

A 755-bp PstI-PstI fragment containing the central Mcp fragment was cloned by PCR (28). Other Mcp subelements were obtained by PCR amplification of the DNA fragments between the following pairs of primers: 5′ GCTCAGAGTACATAAGCG 3′ and 5′ CCCAATCGTTGTAAGTG 3′ (M340); 5′ GCTCAGAGTACATAAGCG 3′ and 5′ ATTCCAAGTCTGAGTTAAG 3′ (M151); 5′ AAACTTAACTCAGACTTGG 3′ and 5′ CCCAATCGTTGTAAGTGT 3′ (M210); and 5′ GCTCAGAGTACATAAGCG 3′ and 5′ TTTGTGTAAGGAGGAAG (M412). The PCR fragments were cloned between either two lox or two frt sites. Ten binding sites for GAL4 (G4) were ligated into the yr plasmid cleaved by NcoI and Eco47III (G4-Δyr).

frt(M412) was inserted in the direct orientation into the yr plasmid cleaved by Eco47III at position −893 from the yellow transcription start site [yr-frt(M412)]. The lox(M412) fragment was inserted into the yr-frt(M412) plasmid cleaved by KpnI at position −343 [yr-frt(M412)-lox(M412)] and into C2-yc between the yellow and white genes [C2-lox(M412)-yc]. The lox(M412) fragment was also inserted into pCaSpeRΔ700 downstream of the white gene [pCaSpeRΔ700-lox(M412)]. The BamHI-BglII fragment of the yellow coding region was cloned into pCaSpeRΔ700-lox(M412) [C2-yc-lox(M412)].

To construct Eye(M412)Y(M412)W, the yr-lox(M412) fragment was cloned into C2-lox(M412)-yc cleaved by XbaI and BamHI. To construct Eye(M412)YW(M412R), the yr-frt(M412) fragment was cloned into C2-yc-lox(M412) cleaved by XbaI and BamHI. To construct Eey(M412) (M412R)YW, the yr-frt(M412)-lox(M412) fragment was cloned into C2-yc cleaved by XbaI and BamHI. Eye(M412R)Y(M412R)W, Eye(M340R)Y(M340)W, and Eye(M210R)Y(M210)W were constructed in the same way as Eye(M412)Y(M412)W.

The I-SceI+126x2-Eye-yr plasmid was described by Rodin and Georgiev in 2005 (59). The frt(M412) fragment was inserted in both orientations into the I-SceI+126x2-Eye-yr plasmid digested with Eco47III at position −893 from the yellow transcription start site. To construct (Eye) (M412R)Y(M412)W and (Eye) (M412)Y(M412)W, the I-SceI+126x2-Eye-yr-frt(M412) fragments were inserted into C2-lox(M412)-yc or C2-lox(M412R)-yc plasmid. (Eye) (M340)Y(M340)W and (Eye) (M210)Y(M210)W were constructed in the same way.

The frt(M412), frt(M210), and frt(M151) fragments were cloned into G4-Δyr cleaved by KpnI. To construct G4(M412)Y(M412R)W, G4(M412R)Y(M412R)W, G4(M210)Y(M210R)W, G4(M210)Y(M210)W, and G4(M151)Y(M151R)W, the G4-Δyr-frt(M412), G4-Δyr-frt(M210), and G4-Δyr-frt(M151) fragments were cloned into the corresponding C2-lox(M412)-yc, C2-lox(M412R)-yc, C2-lox(M210R)-yc, C2-lox(M210)-yc, and C2-lox(M151R)-yc plasmids cleaved by XbaI and BamHI.

The M412 fragment was cloned into the yr plasmid cleaved by NcoI and Eco47III (M412-Δyr). Ten binding sites for GAL4 (G4) were cloned into the M412-Δyr plasmid cleaved by KpnI (M412-Δyr-G4). To construct M412G4Y(M412)W and M412G4Y(M412R)W, the M412-Δyr-G4 fragment was cloned into the C2-lox(M412)-yc and C2-lox(M412R)-yc plasmids cleaved by XbaI and BamHI.

Generation and analysis of transgenic lines.

The construct and P25.7wc plasmid were injected into yacw1118 preblastoderm (36). The resultant flies were crossed with yacw1118 flies, and the transgenic progeny were identified by eye color. The chromosome localization of various transgene insertions was determined by crossing the transformants with the yacw1118 balancer stock containing dominant markers, In(2RL),CyO for chromosome 2 and In(3LR)TM3,Sb for chromosome 3.

The lines with DNA fragment excisions were obtained by crossing the flies bearing the transposons with the Flp (w1118; S2CyO, hsFLP, ISA/Sco;+) or Cre (yw; Cyo, P[w+,cre]/Sco; +) recombinase-expressing lines or with the I-SceI endonuclease-expressing line (v P{v+; hsp70-I-SceI}). The Cre recombinase induces 100% excisions in the next generation. The high levels of FLP recombinase (almost 100% efficiency) and I-SceI endonuclease (90% efficiency) were produced by daily heat shock treatment for 2 h during the first 3 days after hatching. All excisions were confirmed by PCR analysis with the pairs of primers flanking the −893 insertion site (5′ ATCCAGTTGATTTTCAGGGACCA 3′ and 5′ TTGGCAGGTGATTTTGAGCATAC 3′) or the −343 insertion site (5′ TAGATCGTCAAATAAAGTCCCTA 3′ and 5′ GTTTGGTATGATTTTTGGCCTTC 3′) relative to the yellow transcription start site and the insertion site between the yellow and white genes (5′ TTTTCTTGAGCGGAAAAAGCGGA 3′ and 5′ ATCTACATTCTCCAAAAAAGGGT 3′). Details of the crosses used for genetic analysis and the excision of functional elements are available upon request.

To induce GAL4 expression, we used the yw1118; P[w+, tubGAL4]117/TM3,Sb line obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center (no. 5138). To delete the marker mini-white gene, we induced P element-mediated rearrangements by crossing the yw1118; P[w+, tubGAL4]117/TM3,Sb line with the line expressing the transposase Δ2-3 (w; ry506 Sb P{ry+2-3}99B/TM6B, 2536 from the Bloomington Stock Center). In the progeny, we selected the flies that had a white eye phenotype and expressed GAL4 (tested by activation of an enhancerless yellow gene fused to the GAL4 binding region). In the yw1118; P[w+, tubGAL4]117/TM3,Sb line, antibodies against the DNA binding domain of GAL4 (Novus Biological Inc.) recognized only several bands, which indicated that GAL4 did not bind to many sites. In some experiments, we also used a modified hsp70-GAL4 driver located on the CyO chromosome, which was kindly provided by M. Prestel and R. Paro (58). In this transgenic line, the mini-white gene was inactivated by ethyl methanesulfonate. To obtain GAL4 expression, yw1118; CyO hsp70-GAL4 females were crossed with males carrying the test construct. Heat shock treatment (exposure in a water bath at 37°C for 2 h) was performed on the first and second days of pupa hatching.

The yellow (y) phenotype was determined from the level of pigmentation of the abdominal cuticle and wings in 3- to 5-day-old males developing at 25°C. The level of pigmentation (i.e., of y expression) was estimated on an arbitrary five-grade scale, with wild-type expression and the absence of expression assigned scores 5 and 1, respectively.

The white (w) phenotype was determined from eye pigmentation in adult flies. Wild-type white expression determined the bright red eye color; in the absence of white expression, the eyes were white. Intermediate levels of white expression (in increasing order) were reflected in the eye color, ranging from pale yellow to yellow, dark yellow, orange, dark orange, and finally brown or brownish red.

RESULTS

Mapping of the sequences required for insulation within Mcp.

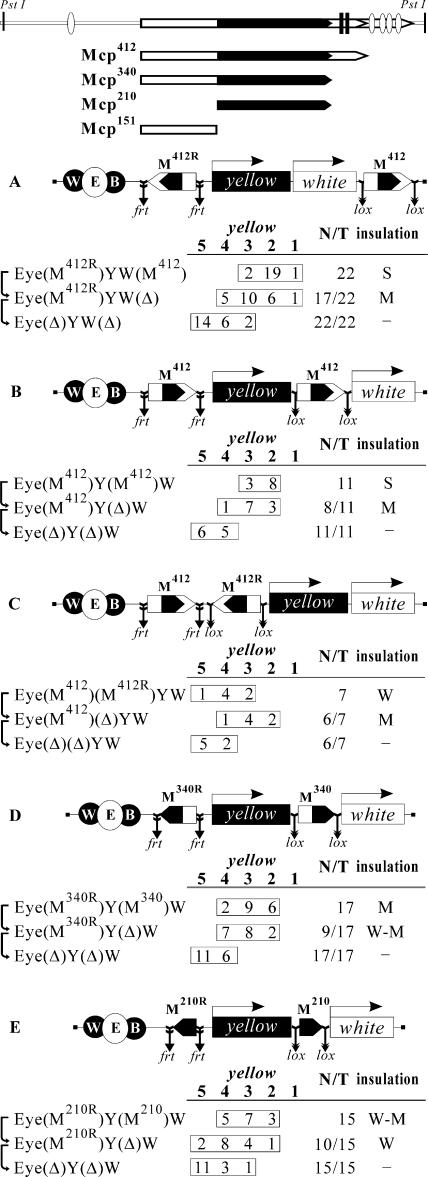

Recently, we identified the 340-bp insulator-like element in the 755-bp Mcp (Fig. 1), designated M340, that partially blocks the yellow and white enhancers (28). M340 is flanked by the silencer (PRE) containing two sites for GAGA binding factor (GAF) and four PHO binding sites (10). It was shown previously that GAF is essential for the enhancer-blocking activity of Fab-7 and SF1 insulators (3, 62, 63). To test whether GAF contributes to insulation, we combined M340 with part of PRE containing GAF binding sites (M412) (Fig. 1). To precisely map the sequences required for insulation in M340, we divided M340 in two overlapping parts: the proximal 151 bp (M151) and the distal 210 bp (M210) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Reductive schemes of transgenic constructs and analysis of transgenic lines for the enhancer-blocking activity of the Mcp insulator. Diagrams in the upper part of the figure show the 755-bp Mcp element and its 412-bp (M412), 340-bp (M340), 210-bp (M210, shown in black), and 151-bp (M151) deletion derivatives. The PRE is shown in white, and the PHO and Gaf binding sites are shown as ovals and black bars, respectively. In the schemes of constructs (drawn not to scale), the Mcp fragments are shown as pentagons with apexes indicating their orientation. The yellow wing (W) and body (B) enhancers are shown as shaded ovals, and the eye enhancer (E) inserted between them is shown as a white oval. The yellow (Y) and white (W) genes are shown as boxes with arrows indicating the direction of their transcription. Downward arrows indicate the target sites of the Flp recombinase (frt) or Cre recombinase (lox); the same sites in construct names are denoted by parentheses. The “yellow” column shows the numbers of transgenic lines with the yellow pigmentation level in the abdominal cuticle (reflecting the activity of the body enhancer); in most of the lines, the pigmentation levels in wing blades (reflecting the activity of the wing enhancer) closely correlated with these scores. The level of pigmentation (i.e., of y expression) was estimated on an arbitrary five-grade scale, with wild-type expression and the absence of expression assigned scores 5 and 1, respectively. N is the number of lines in which flies acquired a new y phenotype upon deletion (Δ) of the specified DNA fragment; T is the total number of lines examined for each particular construct. Arrows on the right side of the column show the order in which deletions in fly lines were made. The column on the right, designated “insulation,” summarizes data on the levels of the enhancer-blocking activity of Mcp fragments with respect to the yellow (Y) enhancer-promoter pair: N, none (the fragment had no influence on pigmentation); W, weak (the flies of most transgenic lines had pigmentation score 4); M-W, medium weak (in equal parts of the transgenic lines tested, the flies had pigmentation scores 4 and 3); M, medium (in most transgenic lines tested, flies had pigmentation score 3); S, strong (in most transgenic lines tested, flies had pigmentation score 2).

As a test system, we chose the yellow and white genes, which have been extensively employed in insulator studies (38). The yellow gene is required for dark pigmentation of larval and adult cuticle and its derivatives. Two upstream enhancers (designated Ey) are responsible for yellow activation in the body cuticle and wing blades, while the enhancer responsible for yellow activation in bristles resides in the intron of the yellow gene (26, 47). In most cases, the transgenic lines carrying enhancerless yellow constructs have yellow wings and body cuticle; i.e., incidental activation of yellow by resident enhancers that might occur close to the site of transposon insertion is a very rare event. The white gene is required for eye pigmentation and is regulated by an eye-specific enhancer (designated Ee [57]). This enhancer was inserted between the yellow wing and body enhancers (designated Eye). Recently, an endogenous insulator was identified at the 3′ end of the white gene (Chetverina et al., unpublished data). This insulator was deleted from the mini-white gene (designated W) in the construct. The yellow gene (designated Y) was inserted upstream of the mini-white gene in the same orientation.

In our previous study (28), the functional interaction between Mcp and M340 was demonstrated. To test for the interplay of two M412 elements in different positions relative to each other and to the enhancers and promoters, we made three constructs in which one M412 copy, flanked by frt sites, was inserted at −893 relative to the yellow transcription start site and the second M412 copy, flanked by lox sites, was inserted downstream of the mini-white gene (Fig. 1A), at +4964 between the yellow and white genes (Fig. 1B), or at −343 between the enhancers and the yellow promoter (Fig. 1C). Throughout the text, parentheses in construct designations enclose the elements flanked by the frt (27) and lox (64) sites at which those elements can be excised in crosses with flies expressing Flp or Cre recombinase (as noted in Materials and Methods). By comparing yellow and white expression in transgenic lines and their derivatives with two, one, or no M412 elements, it is possible to estimate the levels of enhancer blocking by different combinations of M412 elements at the same genomic site.

By scoring yellow phenotypes in derivative transgenic lines with one M412 element inserted at −893 in either the reverse (Fig. 1A) or direct (Fig. 1B) orientation relative to the yellow gene and in the same transgenic lines after deletion of both M412 elements, we found that one M412 copy inserted at −893 blocked the yellow enhancers effectively but not completely (a moderate level of blocking [M]). The second M412 copy located at either tested position downstream of the yellow gene improved insulation, which resulted in stronger blocking of the yellow enhancers (a strong level of blocking [S]). Two M412 copies inserted between the yellow enhancers and the promoter (Fig. 1C) allowed the yellow enhancers to stimulate the promoter better than one copy of this insulator. This finding indicates that the interaction of two M412 elements located between enhancer and promoter partially neutralizes the enhancer-blocking activity.

Thereafter, we repeated experiments with smaller parts of the Mcp element: M340 (Fig. 1D) and M210 (Fig. 1E). These elements flanked by either lox or frt sites were inserted on the sides of the yellow gene at −893 and +4964 relative to the yellow transcription start site. As a result, we found that M210 was less effective than M340 in insulating the yellow enhancers, but the presence of the second copy of M210 or M340 noticeably improved enhancer blocking. Thus, it appears that pairing between two copies of M210 or M340 results in a stronger block of the enhancers located beyond the loop formed by the insulators flanking the yellow gene. Comparing the levels of enhancer blocking mediated by M340 and M412, we found that the part of PRE containing two GAF binding sites contributed to the effectiveness of insulation.

Relative orientation of Mcp elements determines the ability of the eye enhancer to stimulate white expression across paired insulators.

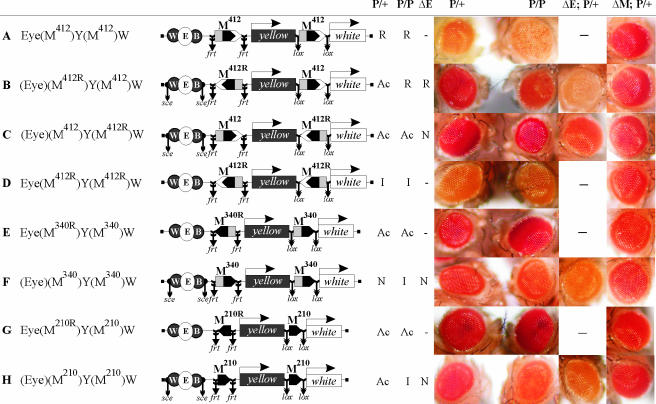

An analysis of eye phenotypes in the transgenic lines described above showed that the eye enhancer failed to effectively stimulate transcription across the pair of M412 elements inserted in the close vicinity of the eye enhancer and the white promoter (Fig. 2A and 3A). This unexpected result contradicts our previous observation that the interaction between M340 and the 755-bp Mcp elements facilitates the eye enhancer-white promoter interaction (28). As the M412 elements were inserted in the same orientation (Fig. 2A), a possible explanation for this contradiction is that the interaction between the eye enhancer and promoter is dependent on the relative orientation of interacting Mcp elements. Alternatively, the white promoter may be directly repressed by the M412 element that contains part of PRE.

FIG. 2.

The ability of the eye enhancer to stimulate transcription across the Mcp elements depends on their relative orientations. Downward arrows indicate the target sites of the Flp recombinase (frt), Cre recombinase (lox), or I-SceI endonuclease (sce); the same sites in construct names are denoted by parentheses. P/+ and P/P refer to transgenic lines heterozygous or homozygous for a construct, respectively. The results obtained in the presence or absence (ΔE) of the eye enhancer are summarized in the corresponding columns. To estimate the role of Mcp elements in eye enhancer-white promoter communication, white expression was compared in the original transgenic lines and their derivatives in which both Mcp elements were deleted (ΔM). Abbreviations: Ac (activation), the eye enhancer better stimulated white expression in the presence of Mcp elements; N (neutral), Mcp elements had no significant influence on white activation by the eye enhancer; I (insulation), Mcp elements blocked the activity of the eye enhancer; R (repression), Mcp elements repressed white expression. Photographs show the eyes of flies from the same transgenic line heterozygous (P/+) or homozygous (P/P) for the construct and eye phenotypes in heterozygous flies after deletion of either the eye enhancer (ΔE; P/+) or both Mcp elements (ΔM; P/+). Other designations are as in Fig. 1.

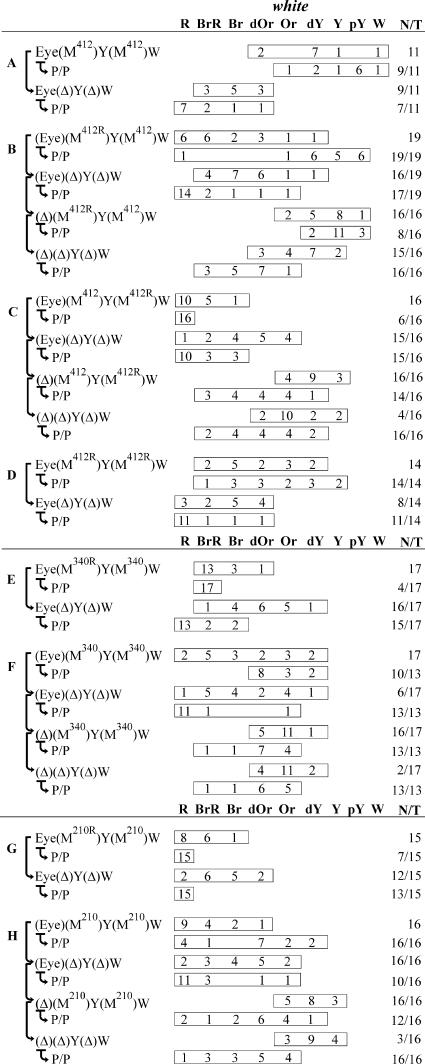

FIG. 3.

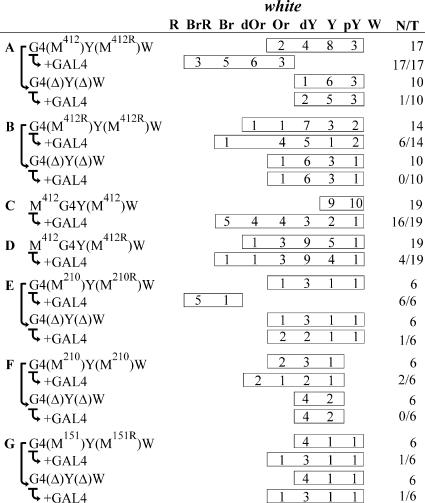

Dependence of the ability of the eye enhancer to stimulate transcription across paired Mcp insulators on their relative orientations. For the schemes of constructs, see Fig. 2. The “white” column shows the numbers of transgenic lines with different levels of white pigmentation in the eyes (reflecting the activity of the eye enhancer). P/P refers to transgenic lines homozygous for the construct. Wild-type white expression determined the bright red eye color (R); in the absence of white expression, the eyes were white (W). Intermediate levels of pigmentation with the eye color ranging from pale yellow (pY) through yellow (Y), dark yellow (dY), orange (Or), dark orange (dOr), and brown (Br) to brownish red (BrR) reflect increasing levels of white expression. Other designations are as in Fig. 1 and 2.

To test these assumptions, we made three additional constructs in which M412 elements were inserted at −893 and +4964 in the head-to-head (Fig. 2B) or tail-to-tail (Fig. 2C) orientations or both M412 elements were inserted in the reverse orientation (Fig. 2D). To check the contributions of the eye enhancer and tested insulator elements to white expression, the eye and yellow enhancers were flanked by 126-bp direct repeats and sites for the rare-cleaving I-SceI endonuclease, which permits excision of enhancers, as described in Materials and Methods (59).

In all three series of transgenic lines, the yellow enhancers were blocked to similar extents (data not shown), which suggested that the orientation of M412 elements relative to each other, to the enhancers, or to the promoter is not essential for the insulation of yellow. To determine how M412 affects white expression, we compared eye pigmentation in flies carrying enhancerless transgenic constructs in the presence or absence of the M412 elements (Fig. 3Band C). After deletion of the eye enhancer, we were able to estimate whether M412 directly influences the activity of the white promoter. Repression of white expression was observed when M412 was inserted so that the GAF sites were closer to the white promoter (Fig. 3B). In the opposite orientation, M412 had no influence on white expression, which might be attributed to the blocking of repressor by the adjacent insulator element (Fig. 2C and 3C). The M412 element repressed white only when it was located near the white promoter; in addition, it had no influence on yellow expression in bristles, which is regulated by the enhancer located in the yellow intron (data not shown).

We then examined eye pigmentation in flies carrying original transgenic constructs and derivatives in which both insulators were deleted. First, we compared white expression in transgenic lines in which M412 did not repress white expression (Fig. 2C and D and Fig. 3C and D). When the M412 elements were inserted in the opposite orientations, the eye enhancer strongly activated the white promoter in all transgenic lines tested, either heterozygous or homozygous for the construct (Fig. 2C and 3C). Deletion of both M412 elements led to the weakening of white activation. Thus, the interaction between the M412 elements inserted in the opposite orientations facilitates communication between the eye enhancer and the white promoter across the yellow gene.

When the M412 elements had the same orientation, white expression in transgenic lines heterozygous for the construct was stronger than in derivative transgenic lines without these elements (Fig. 2D and 3D). In flies homozygous for the construct, however, the activity of the eye enhancer was almost completely blocked in the presence of two M412 elements. These results indicate that relative orientation of M412 elements is essential for communication between the eye enhancer and the white promoter.

Similar results were obtained with transgenic lines in which M412 repressed white expression (Fig. 2A and B and Fig. 3A and B). Again, when the M412 elements were inserted in the opposite orientations, they facilitated white stimulation by the eye enhancer (Fig. 2B and 3B); in transgenic lines with both M412 elements in the same orientation, white expression was strongly reduced compared to that in derivative transgenic lines in which these elements were deleted (Fig. 2A and 3A). In lines homozygous for the construct, white expression was repressed in both variants, suggesting that pairing in homozygous lines strengthens the repression. Such pairing-dependent repression is typical of PRE silencing (40, 55).

As in the previous experiments, we tested the M340 and M210 elements inserted in the opposite orientations (Fig. 2E and G and Fig. 3E and G) and also made constructs in which these elements had the same orientation (Fig. 2F and H and Fig. 3F and H). In the last two constructs, the enhancers were flanked by I-SceI sites to permit excision. By comparing eye pigmentation in enhancerless transgenic lines in the presence or absence of M340/M210 elements (Fig. 2F and H and Fig. 3F and H), we concluded that the M340 and M210 elements inserted in the same orientation as M412 (Fig. 2A) had no influence on white expression. Therefore, the part of PRE including GAF binding sites indeed functions as a short-range repressor of the white promoter.

Then, we checked whether the relative orientation of M340 (Fig. 2E and F and Fig. 3E and F) or M210 (Fig. 2G and H and Fig. 3G and H) elements is important for white stimulation by the eye enhancer. As in the case of M412, orientation of these elements inserted between the yellow enhancers and the promoter had no influence on the level of insulation of the yellow gene (data not shown). In the opposite orientation, both elements improved eye enhancer-white promoter communication in all transgenic lines, either heterozygous or homozygous for the construct. When these elements were inserted in the same orientation, the eye enhancer still activated white transcription. However, the levels of activation in the presence or absence of these elements were similar, indicating that the interaction between them did not facilitate enhancer-promoter communication. In transgenic lines homozygous for the construct, however, the eye enhancer was blocked. These results suggest that communication between the eye enhancer and the white promoter partially depends on the relative orientation of M340 or M210 elements. Hence, M210 is the minimal element capable of interaction in an orientation-dependent manner.

Distant stimulation of the white promoter by the GAL4 activator depends on the relative orientation of interacting Mcp elements.

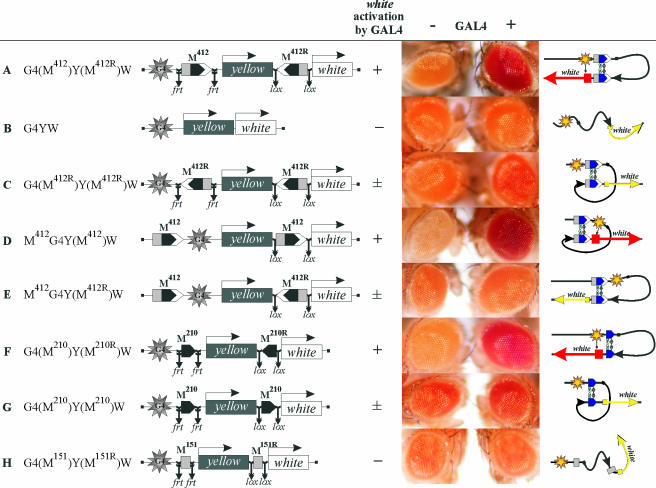

To directly demonstrate that pairing between Mcp elements facilitates interaction between distantly located regulatory elements, we used the yeast GAL4 activator. In yeast, the level of GAL4 activation decreases with an increase in the distance between GAL4 binding sites and a promoter (18, 29, 67). To test whether the interaction between M412 elements can facilitate white stimulation by GAL4, we used the yellow gene as a spacer DNA. The wing and body enhancers were deleted. Ten GAL4 binding sites (designated G4) were inserted at −893 relative to the yellow transcription start site. As a result, the distance between the mini-white gene and the GAL4 binding sites was almost 5 kb. To express GAL4 protein, we used the transgenic line carrying the GAL4 gene under control of the ubiquitous tubulin promoter (Fig. 4 and 5). Some of experiments were repeated with the hsp70-GAL4 driver, which induced GAL4 expression only under heat shock (58). As experiments with both GAL4 drivers produced similar results (data not shown), only the data obtained with the tubulin-GAL4 driver are considered below.

FIG. 4.

Testing of the interaction between Mcp elements by the criterion of long-distance white activation by GAL4. The GAL4 binding sites (indicated as G4) are at a distance of approximately 5 kb from the white promoter. “+ GAL4” indicates that eye phenotypes were examined in transgenic lines after induction of GAL4 expression. Levels of activation under the effect of GAL4: −, no activation of white; ±, weak activation of white in less than half of the transgenic lines tested; +, strong activation of white in most transgenic lines tested. Other designations are as in Fig. 1 and 2. The column on the right shows models of pairing between the Mcp insulators. The red and yellow arrows indicate strong and weak white activation, respectively. The yellow star shows the GAL4 binding sites.

FIG. 5.

Experimental evidence that interacting Mcp elements facilitate stimulation of white by a distantly located GAL4 activator. Note: “+ GAL4” indicates that eye phenotypes were examined in transgenic lines after induction of GAL4 expression. The “white” column shows the numbers of transgenic lines with different levels of white pigmentation in the eyes (reflecting the activity of the eye enhancer). Wild-type white expression determined the bright red eye color (R); in the absence of white expression, the eyes were white (W). Intermediate levels of pigmentation with the eye color ranging from pale yellow (pY) through yellow (Y), dark yellow (dY), orange (Or), dark orange (dOr), and brown (Br) to brownish red (BrR) reflect increasing levels of white expression. N is the number of lines in which flies acquired a new y phenotype upon induction of GAL4 or deletion (Δ) of the specified DNA fragment; T is the total number of lines examined for each particular construct.

Initially, we checked whether the interaction between M412 elements inserted in the opposite orientations facilitated white activation by GAL4. When the M412 elements were located in the vicinity of the GAL4 binding sites and the white promoter in the head-to-head orientation, GAL4 strongly induced white expression (Fig. 4A and 5A). When M412 elements were deleted from transgenic lines, GAL4 lost the ability to stimulate white expression at the 5-kb distance (Fig. 4B and 5). Hence, GAL4 is a distance-dependent activator in Drosophila, as well as in yeast, and the interaction between the M412 elements places the GAL4 activator in close proximity to the transcriptional complex at the white promoter, facilitating GAL4-mediated activation.

We then tested whether white activation by GAL4 depended on the relative orientation of M412 elements. The proximal M412 element adjacent to the GAL4 binding sites was inserted in the same orientation as the distal element (Fig. 4C and 5B). GAL4 expression in transgenic lines weakly increased eye pigmentation only in a minor part of the transgenic lines (Fig. 4C and 5B). Again, GAL4 failed to activate white when both M412 elements were deleted. These results show that the interacting M412 elements bring together GAL4 and the white promoter on the one hand but do not permit strong stimulation of white by GAL4 on the other hand.

To explain these results, we proposed that the pairing of M412 elements may produce two loop configurations, depending on their relative orientations (Fig. 4). If so, the GAL4 binding sites placed on the inner side of M412 should lead to strong white activation by GAL4 when both M412 elements are inserted in the same orientation. To check this assumption, we inserted the GAL4 binding sites between the M412 elements located in the same orientation (Fig. 4D and 5C). In this case, GAL4 effectively stimulated white expression, while deletion of the distal M412 element abolished white activation by GAL4. When the M412 elements were inserted in the opposite orientation (Fig. 4E and 5D), white activation by GAL4 was strongly reduced. These results confirmed the proposed model.

To test whether the minimal M210 element had the same property as M412, we made two constructs in which the M210 elements were inserted either in the opposite orientation (Fig. 4F and 5E) or in the same orientation (Fig. 4G and 5F) between the GAL4 binding sites and the white promoter. These results showed that the interacting M210 elements effectively facilitated white stimulation by GAL4 only when the M210 elements were inserted in the opposite orientation.

Finally, we tested whether the M151 elements could interact and support communication between the GAL4 activator and the white promoter. The M151 elements were inserted in the opposite orientations between the GAL4 binding sites and the white promoter (Fig. 4H and 5G). In the transgenic lines tested, GAL4 failed to stimulate white transcription, which indicates that the M151 elements did not support stimulation of white expression by GAL4 from a distance.

DISCUSSION

It was demonstrated in our previous paper that the interaction between M340 and the 755-bp Mcp facilitates white stimulation by the eye enhancer (28). In this study, we mapped the 210-bp element that supports pairing in M340. To demonstrate interactions between Mcp elements, we used the yeast GAL4 activator that binds to the upstream activating sequences. Yeast enhancers, compared to their metazoan counterparts, are less flexible in terms of distance and position relative to the regulated promoter (18, 29, 67). Several proteins and DNA elements that have been identified can facilitate long-distance communication between enhancers and promoters in metazoans (11, 12, 16, 21, 22, 42, 43, 46, 54, 57, 61, 68, 70, 73, 75). This class of factors may support the stability of DNA loops between enhancers and promoters, e.g., by holding these elements in close proximity to each other. Here, we have found that the GAL4 activator cannot efficiently activate the white promoter when its binding sites are separated by the yellow gene and, hence, are located at a distance of 5 kb from the promoter. The interaction between Mcp elements inserted in the vicinity of GAL4 binding sites and the white promoter supports consistent white stimulation by GAL4.

The relative orientation of the Mcp elements defines the mode of loop formation that either allows or blocks stimulation of the white promoter by the GAL4 activator (Fig. 4). The orientation-dependent interaction may be accounted for by at least two proteins bound to the M210 sequences that are involved in specific protein-protein interactions. When these elements are located in the inverted orientation, the loop configuration is favorable for communication between regulatory elements located outside the loop (Fig. 4A and F). The loop formed by two insulators located in the same orientation juxtaposes two elements located inside and outside the loop, which leads to isolation of the GAL4 binding sites and the white promoter placed on the opposite sides of the Mcp elements (Fig. 4C and G). At the same time, the GAL4 activator bound to the inner side of the Mcp element can stimulate the promoter located outside the Mcp element (Fig. 4D). In the same way, the codirectional Mcp elements partially suppress the activation of white by the eye enhancer located outside the loop formed by the Mcp elements. In contrast to GAL4, the eye enhancer can stimulate the white promoter from a large distance. However, the interaction between the Mcp elements can either stabilize (Mcp elements are in the opposite orientations) or suppress (Mcp elements are in the same orientation) the enhancer-promoter communication. In the transgenic lines homozygous for the construct, the interaction between the Mcp elements located on the homologous chromosomes appears to provide for more effective isolation of the eye enhancer.

Widely accepted models concerning the mechanisms of insulator action suggest that insulators interact either with the nuclear matrix/nuclear envelope or with each other to form “topologically independent” chromatin loops, which allow enhancer-promoter interactions only within the loop domain (24, 38, 53, 72). However, the conclusion that formation of chromatin loops by interacting insulators is important for enhancer blocking is supported only by the results of experiments with artificial insulators. An insulator-like element was constructed in vitro by use of a sequence-specific DNA binding protein (lac repressor) known to cause stable DNA looping (5). The insulator function was entirely dependent on the formation of a DNA loop that topologically isolated the enhancer from the promoter. Likewise, enclosing the simian virus 40 enhancer in a DNA loop could block activation of gene expression in HeLa cells (1). Here, we demonstrate for the first time that the Mcp insulator located downstream of the yellow gene significantly improves the enhancer-blocking activity of the insulator located between the enhancers and promoter of the yellow gene. Apparently, the interaction between the Mcp insulators results in the formation of a loop that restricts communication between the enhancers located outside the loop and promoters located inside it. It is also possible that the interaction between complexes bound to the Mcp insulators may result in their stabilization, improving the enhancer-blocking activity.

The role of Mcp and other boundary elements in transcriptional regulation of Abd-B is as yet uncertain. The generally accepted model suggests that the insulator/boundary element functions as a barrier separating iab domains differing in the status of chromatin (45, 66). However it was recently found that replacement of the Fab-7 boundary element by the Su(Hw) or scs insulator prevented all distal enhancers from interacting with the Abd-B promoter (33). This fact suggests that the boundary elements in Abd-B have a more complex function, rather than merely acting as the barrier between the iab domains (45, 66). In a recent study, Cleard et al. directly demonstrated the interaction between the Fab-7 boundary and the Abd-B promoter (17). They concluded that the role of boundaries in Abd-B is to bring elements of the cis-regulatory regions into close proximity to the promoter. Thus, it seems possible that M210 not only serves as a boundary between the iab-4 and iab-5 domains but is also involved in long-distance communication between the iab-5 enhancer and the Abd-B promoter. A similar role in regulation of long-distance interactions between the iab enhancers and the Abd-B promoter was proposed for PTS elements (16, 42, 43, 73). Recently, it was shown that Su(Hw) (37) and CTCF (44) insulators can support long-distance interactions, which indicates that insulator-bound proteins are essential for such communication. The extensive region upstream of the Abd-B gene is required for tethering the iab regulatory domains to the Abd-B promoter (65). It may well be that the proteins bound to M210 generate a code for very specific interactions with some discrete elements in this region of the Abd-B promoter. Further studies are necessary for elucidating the mechanisms that regulate long-distance enhancer-promoter interactions in the Abd-B gene.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to M. Prestel and R. Paro for providing the CyO, hsp70-GAL4 line.

This study was supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (project no. N 06-04-48360), the Molecular and Cell Biology Program of the Russian Academy of Sciences, and an International Research Scholar Award from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (to P.G.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 February 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ameres, S. L., L. Drueppel, K. Pfleiderer, A. Schmidt, W. Hillen, and C. Berens. 2005. Inducible DNA-loop formation blocks transcriptional activation by an SV40 enhancer. EMBO J. 24:358-367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barges, S., J. Mihaly, M. Galloni, K. Hagstrom, M. Muller, G. Shanower, and P. Schedl, H. Gyurkovics, and F. Karch. 2000. The Fab-8 boundary defines the distal limit of the bithorax complex iab-7 domain and insulates iab-7 from initiation elements and a PRE in the adjacent iab-8 domain. Development 127:779-790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belozerov, V. E., P. Majumder, P. Shen, and H. N. Cai. 2003. A novel boundary element may facilitate independent gene regulation in the Antennapedia complex of Drosophila. EMBO J. 22:3113-3121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blackwood, E. M., and J. T. Kadonaga. 1998. Going the distance: a current view of enhancer action. Science 281:60-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bondarenko, V. A., Y. V. Liu, Y. I. Jiang, and V. M. Studitsky. 2003. Communication over a large distance: enhancers and insulators. Biochem. Cell Biol. 81:241-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bondarenko,V. A., Y. I. Jiang, and V. M. Studitsky. 2003. Rationally designed insulator-like elements can block enhancer action in vitro. EMBO J. 22:4728-4737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boulet, A. M., A. Lloyd, and S. Sakonju. 1991. Molecular definition of the morphogenetic and regulatory functions and the cis-regulatory elements of the Drosophila Abd-B homeotic gene. Development 111:393-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Busturia, A., and M. Bienz. 1993. Silencers in abdominal-B, a homeotic Drosophila gene. EMBO J. 12:1415-1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Busturia, A., C. D. Wightman, and S. Sakonju. 1997. A silencer is required for maintenance of transcriptional repression throughout Drosophila development. Development 124:4343-4350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Busturia, A., A. Lloyd, F. Bejarano, M. Zavortink, H. Xin, and S. Sakonju. 2001. The MCP silencer of the Drosophila Abd-B gene requires both Pleoihomeotic and GAGA factor for the maintenance of repression. Development 128:2163-2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calhoun, V. C., A. Stathopoulos, and M. Levine. 2002. Promoter-proximal tethering elements regulate enhancer-promoter specificity in the Drosophila Antennapedia complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:9243-9247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calhoun, V. C., and M. Levine. 2003. Long-range enhancer-promoter interactions in the Scr-Antp interval of the Drosophila Antennapedia complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:9878-9883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carter, D., L. Chakalova, C. S. Osborne, Y. F. Dai, and P. Fraser. 2002. Long-range chromatin regulatory interactions in vivo. Nat. Genet. 32:623-626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Celniker, S. E., S. Sharma, D. J. Keelan, and E. B. Lewis. 1990. The molecular genetics of the bithorax complex of Drosophila: cis-regulation in the Abdominal-B domain. EMBO J. 9:4227-4286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chambeyron, S., and W. A. Bickmore. 2004. Does looping and clustering in the nucleus regulate gene expression? Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 16:256-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen, Q., L. Lin, S. Smith, Q. Lin, and J. Zhou. 2005. Multiple promoter targeting sequences exist in Abdominal-B to regulate long-range gene activation. Dev. Biol. 286:629-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cleard, F., Y. Moshkin, F. Karch, and R. K. Maeda. 2006. Probing long-distance regulatory interactions in the Drosophila melanogaster bithorax complex using Dam identification. Nat. Genet. 38:931-935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Bruin, D., Z. Zaman, R. A. Liberatore, and M. Ptashne. 2001. Telomere looping permits gene activation by a downstream UAS in yeast. Nature 409:109-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Laat, W., and F. Grosveld. 2003. Spatial organization of gene expression: the active chromatin hub. Chromosome Res. 11:447-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dillon, N., and P. Sabbattini. 2000. Functional gene expression domains: defining functional unit of eukaryotic gene regulation. Bioessays 22:657-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dorsett, D. 1999. Distant liaisons: long range enhancer-promoter interactions in Drosophila. Curr. Opin. Genet. 9:505-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drissen, R., R. J. Palstra, N. Gillemans, E. Splinter, F. Grosveld, S. Philipsen, and W. de Laat. 2004. The active spatial organization of the beta-globin locus requires the transcription factor EKLF. Genes Dev. 18:2485-2490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duncan, I. 1987. The bithorax complex. Annu. Rev. Genet. 21:285-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Felsenfeld, G., B. Burgess-Beusse, C. Farrell, M. Gaszner, R. Ghirlando, S. Huang, C. Jin, M. Litt, F. Magdinier, V. Mutskov, Y. Nakatani, H. Tagami, A. West, and T. Yusufrai. 2004. Chromatin boundaries and chromatin domains. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 69:245-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galloni, M., H. Gyurkovics, P. Schedl, and F. Karch. 1993. The bluetail transposon: evidence for independent cis-regulatory domains and domain boundaries in the bithorax complex. EMBO J. 12:1087-1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geyer, P. K., and V. G. Corces. 1987. Separate regulatory elements are responsible for the complex pattern of tissue-specific and developmental transcription of the yellow locus in Drosophila melanogaster. Genes Dev. 1:996-1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Golic, K. G., and S. Lindquist. 1989. The FLP recombinase of yeast catalyzes site-specific recombination in the Drosophila genome. Cell 59:499-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gruzdeva, N., O. Kyrchanova, A. Parshikov, A. Kullyev, and P. Georgiev. 2005. The Mcp element from the bithorax complex contains an insulator that is capable of pairwise interactions and can facilitate enhancer-promoter communication. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:3682-3689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guarente, L., and E. Hoar. 1984. Upstream activation sites of the CYC1 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae are active when inverted but not when placed downstream of the “TATA box.” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:7860-7864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gyurkovics, H., J. Gausz, J. Kummer, and F. Karch. 1990. A new homeotic mutation in the Drosophila bithorax complex removes a boundary separating two domains of regulation. EMBO J. 9:2579-2585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hagstrom, K., M. Muller, and P. Schedl. 1996. Fab-7 functions as a chromatin domain boundary to ensure proper segment specification by the Drosophila bithorax complex. Genes Dev. 10:3202-3215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hagstrom, K., M. Muller, and P. Schedl. 1997. A Polycomb and GAGA dependent silencer adjoin the Fab-7 boundary in the Drosophila bithorax complex. Genetics 146:1365-1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hogga, I., J. Mihaly, S. Barges, and F. Karch. 2001. Replacement of Fab-7 by the gypsy or scs insulator disrupts long-distance regulatory interactions in the Abd-B gene of the bithorax complex. Mol. Cell 8:1145-1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karch, F., B. Weiffenbach, M. Peifer, W. Bender, I. Duncan, S. Celniker, M. Crosby, and E. B. Lewis. 1985. The abdominal region of the bithorax complex. Cell 43:81-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karch, F., M. Galloni, L. Sipos, J. Gausz, H. Gyurkovics, and P. Schedl. 1994. Mcp and Fab-7: molecular analysis of putative boundaries of cis-regulatory domains in the bithorax complex of Drosophila melanogaster. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:3138-3146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kares, R. E., and G. M. Rubin. 1984. Analysis of P transposable element functions in Drosophila. Cell 38:135-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kravchenko, E., E. Savitskaya, O. Kravchuk, A. Parshikov, P. Georgiev, and M. Savitsky. 2005. Pairing between gypsy insulators facilitates the enhancer action in trans throughout the Drosophila genome. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:9283-9291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuhn, E. J., and P. K. Geyer. 2003. Genomic insulators: connecting properties to mechanism. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 15:259-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levine, M. R., and R. Tjian. 2003. Transcription regulation and animal diversity. Nature 424:147-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levine, S. S., I. F. G. King, and R. E. Kingston. 2004. Division of labor in Polycomb group repression. Trends Biochem. Sci. 29:478-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lewis, E. B. 1978. A gene complex controlling segmentation in Drosophila. Nature 276:565-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin, Q., D. Wu, and J. Zhou. 2003. The promoter targeting sequence facilitates and restricts a distant enhancer to a single promoter in the Drosophila embryo. Development 130:519-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin, Q., Q. Chen, L. Lin, and J. Zhou. 2004. The promoter targeting sequence mediates epigenetically heritable transcription memory. Genes Dev. 18:2639-2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ling, J. Q., T. Li, J. F. Hu, T. H. Vu, H. L. Chen, X. W. Qiu, A. M. Cherry, and A. R. Hoffman. 2006. CTCF mediates interchromosomal colocalization between Igf2/H19 and Wsb1/Nf1. Science 312:269-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maeda, R. K., and F. Karch. 2006. The ABC of the BX-C: the bithorax complex explained. Development 133:1413-1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mahmoudi, T., K. R. Katsani, and C. P. Verrijzer. 2002. GAGA can mediate enhancer function in trans by linking two separate DNA molecules. EMBO J. 21:1775-1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martin, M., Y. B. Meng, and W. Chia. 1989. Regulatory elements involved in the tissue-specific expression of the yellow gene of Drosophila. Mol. Gen. Genet. 218:118-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McCall, K., M. B. O'Connor, and W. Bender. 1994. Enhancer traps in the Drosophila bithorax complex mark parasegmental domains. Genetics 138:387-399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mihaly, J., I. Hogga, J. Gausz, H. Gyurkovics, and F. Karch. 1997. In situ dissection of the Fab-7 region of the bithorax complex into a chromatin domain boundary and a Polycomb-response element. Development 124:1809-1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mihaly, J., I. Hogga, S. Barges, M. Galloni, R. K. Mishra, K. Hagstrom, M. Muller, P. Schedl, L. Sipos, J. Gausz, H. Gyurkovics, and F. Karch. 1998. Chromatin domain boundaries in the bithorax complex. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 54:60-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mihaly, J., S. Barges, L. Sipos, R. Maeda, F. Cleard, I. Hogga, W. Bender, H. Gyurkovics, and F. Karch. 2006. Dissecting the regulatory landscape of the Abd-B gene of the bithorax complex. Development 133:2983-2993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Muller, M., K. Hagstrom, H. Gyurkovics, V. Pirrotta, and P. Schedl. 1999. The Mcp element from the Drosophila melanogaster bithorax complex mediates long-distance regulatory interactions. Genetics 153:1333-1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oki, M., and R. T. Kamakaka. 2002. Blockers and barriers to transcription: competing activities? Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14:299-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Petrascheck, M., D. Escher, T. Mahmoudi, C. P. Verrijer, W. Schaffner, and A. Barberis. 2005. DNA looping induced by a transcriptional enhancer in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:3743-3750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pirrotta, V., and D. S. Gross. 2005. Epigenetic silencing mechanisms in budding yeast and fruit fly: different paths, same destinations. Mol. Cell 18:395-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ptashne, M. 1986. Gene regulation by proteins acting nearby and at distance. Nature 322:697-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Qian, S., B. Varjavand, and V. Pirrotta. 1992. Molecular analysis of the zeste-white interaction reveals a promoter-proximal element essential for distant enhancer-promoter communication. Genetics 131:79-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rank, G., M. Prestel, and R. Paro. 2002. Transcription through intergenic chromosomal memory elements of the Drosophila bithorax complex correlates with an epigenetic switch. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:8026-8034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rodin, S., and P. Georgiev. 2005. Handling three regulatory elements in one transgene: combined use of cre-lox, FLP-FRT and I-SceI recombination systems. BioTechniques 39:871-875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sanchez-Herrero, E., I. Vernos, R. Marco, and G. Morato. 1985. Genetic organization of Drosophila bithorax complex. Nature 313:108-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sanchez-Herrero, E. 1991. Control of the expression of the bithorax complex Abdominal-A and Abdominal-B by cis-regulatory regions in Drosophila embryos. Development 111:437-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schweinsberg, S., and P. Schedl. 2004. Developmental modulation of Fab-7 boundary function. Development 131:4743-4749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schweinsberg, S., K. Hagstrom, D. Gohl, P. Schedl, R. P. Kumar, R. Mishra, and F. Karch. 2004. The enhancer-blocking activity of the Fab-7 boundary from the Drosophila bithorax complex requires GAGA-factor-binding sites. Genetics 168:1371-1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Siegal, M. L., and D. L. Hartl. 2000. Application of Cre/loxP in Drosophila. Site-specific recombination and transgene co-placement. Methods Mol. Biol. 136:487-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sipos, L., J. Mihaly, F. Karch, P. Schedl, J. Gausz, and H. Gyurkovics. 1998. Transvection in the Drosophila Abd-B domain: extensive upstream sequences are involved in anchoring distant cis-regulatory regions to the promoter. Genetics 149:1031-1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sipos, L., and H. Gyurkovics. 2005. Long-distance interactions between enhancers and promoters. The case of the Abd-B domain of the Drosophila bithorax complex. FEBS J. 272:3253-3259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Struhl, K. 1984. Genetic properties and chromatin structure of the yeast gal regulatory element: an enhancer-like sequence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:7865-7869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Su, W., S. Jackson, R. Tjian, and H. Echols. 1991. DNA looping between sites for transcriptional activation: self-association of DNA-bound Sp1. Genes Dev. 5:820-826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tolhuis, B., R. J. Palstra, E. Splinter, F. Grosveld, and W. de Laat. 2002. Looping and interaction between hypersensitive sites in the active β-globin locus. Mol. Cell 10:1453-1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vakoc, C. R., D. L. Letting, N. Gheldof, T. Sawado, M. A. Bender, M. Groudine, M. J. Weiss, J. Dekker, and G. A. Blobel. 2005. Proximity among distant regulatory elements at the β-globin locus requires GATA-1 and FOG-1. Mol. Cell 17:453-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vazquez, J., M. Muller, V. Pirrotta, and J. W. Sedat. 2006. The Mcp element mediates stable long-range chromosome-chromosome interactions in Drosophila. Mol. Biol. Cell 17:2158-2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.West, A. G., and P. Fraser. 2005. Remote control of gene transcription. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14:R101-R111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhou, J., and M. Levine. 1999. A novel cis-regulatory element, the PTS, mediates an antiinsulator activity in the Drosophila embryo. Cell 99:567-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhou, J., S. Barolo, P. Szymanski, and M. Levine. 1996. The Fab-7 element of the bithorax complex attenuates enhancer-promoter interactions in the Drosophila embryo. Genes Dev. 10:3195-3201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhou, J., H. Ashe, C. Burks, and M. Levine. 1999. Characterization of the transvection mediating region of the Abdominal-B locus in Drosophila. Development 126:3057-3065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]