Abstract

Gastrointestinal (GI) disease is a debilitating feature of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection that can occur in the absence of histopathological abnormalities or identifiable enteropathogens. However, the mechanisms of GI dysfunction are poorly understood. The present study was undertaken to characterize changes in resident and inflammatory cells in the enteric nervous system (ENS) of macaques during the acute stage of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection to gain insight into potential pathogenic mechanisms of GI disease. Ganglia from duodenum, ileum, and colon were examined in healthy and acutely infected macaques by using a combination of routine histology, double-label immunofluorescence and in situ hybridization. Evaluation of tissues from infected macaques showed progressive infiltration of myenteric ganglia by CD3+ T cells and IBA1+ macrophages beginning as early as 8 days postinfection. Quantitative image analysis revealed that the severity of myenteric ganglionitis increased with time after SIV infection and, in general, was more severe in ganglia from the small intestine than in ganglia from the colon. Despite an abundance of inflammatory cells in myenteric ganglia during acute infection, the ENS was not a target for virus infection. This study provides evidence that the ENS may be playing a role in the pathogenesis of GI disease and enteropathy in HIV-infected people.

Gastrointestinal (GI) disorders, including chronic diarrhea and malabsorption, are frequent manifestations of human and simian immunodeficiency virus (HIV and SIV) infections (3, 17, 18, 22, 29, 30, 33, 39, 43, 56, 60, 61). Although these disorders are generally not life-threatening, they are a major cause of morbidity and contribute to the weight loss and wasting commonly seen in patients with AIDS. Opportunistic pathogens are frequently identified in the GI tracts of HIV-infected patients with GI disease and likely contribute to the development of this disorder. However, in as many as one-third of HIV-infected individuals with GI symptoms, no opportunistic pathogens can be identified. Clinically, these patients demonstrate evidence of increased small intestinal permeability and malabsorption of lipids and sugar without overt histological changes in the intestinal mucosa (3, 22, 25, 56). In these patients it has been proposed that HIV itself contributes to the development of GI symptoms, either directly or indirectly; hence, the term HIV enteropathy has been applied to this syndrome. Although GI symptoms tend to be more pronounced as disease progresses, enteropathy can occur at all stages of infection (29). There is ample evidence that functional deficits of the GI tract are present at the early stage of disease with both HIV and SIV infections (17, 18, 23, 25, 33, 43, 60). However, to date, the underlying mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of HIV enteropathy remain unclear.

Normal GI function requires the presence of an intact mucosal barrier, adequate intestinal blood flow and proper function of the enteric nervous system (ENS). The ENS is the most complicated nervous structure outside of the central nervous system (CNS) and is a key player in many GI tract functions including motility, the absorption of water and nutrients, and the maintenance of mucosal homeostasis (16). Recent reports have demonstrated that the ENS plays an important role in the pathogenesis of diarrhea caused by several enteric pathogens, including rotavirus (6, 26, 34) and Escherichia coli and Vibrio cholerae (37, 42). In addition, some diseases typically thought of as “central nervous system” disorders, such as Parkinson's disease, also affect the ENS (44, 45, 49, 58) and likely contribute to the pathogenesis of GI dysfunction commonly associated with this disorder. Like Parkinson's disease, HIV infection also affects the CNS, causing encephalitis and subcortical dementia in infected individuals (12, 36, 38). However, little information is known regarding the effects of HIV infection on the ENS with the exception of a few early reports describing reduction in axonal density in the jejunum of some HIV-infected patients (2, 15, 35). These observations collectively demonstrate the close homology and interconnectedness between the ENS and CNS in their susceptibility and response to infectious and degenerative insults and highlight the potential importance of the ENS in the pathogenesis of GI disorders.

HIV infection causes a broad spectrum of neurological diseases in infected individuals (36), including AIDS dementia complex (12, 38), HIV-related peripheral neuropathy (20, 41, 47, 55), and autonomic neuropathy (9, 52). Since HIV does not directly infect neurons, neurological disease is believed to be the result of neuronal injury and degeneration likely mediated by substances such as chemokines and cytokines produced locally by inflammatory cells within the brain and nerves (20, 21, 50, 55, 63). Given this large body of data regarding the neuropathogenesis of HIV infection and the link between the central and enteric nervous systems, we hypothesized that HIV infection causes GI disease in infected individuals through a similar pathological mechanism involving inflammation and neuronal injury and loss within the ENS. In the present study, we utilized the simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected macaque model of HIV infection to investigate the role of the ENS in the pathogenesis of HIV enteropathy. The SIV/macaque model is particularly useful for studying the pathogenesis of HIV infection in the GI tract because, like HIV-infected people, SIV-infected macaques also develop an enteropathy early after virus infection (17, 18, 60). We describe here an enteric neuropathy in the GI tract of SIV-infected rhesus macaques that is characterized by infiltration of myenteric ganglia by T cells and macrophages. These observations provide evidence that the ENS may play a role in the pathogenesis of HIV enteropathy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and tissue collection.

Gastrointestinal tissues from a total of eight adult rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) were evaluated retrospectively in the current study (Table 1) . Six animals were inoculated intravenously with 50 ng of SIVmac251, and two each were euthanized at 8, 13, and 21 days postinoculation (dpi). Two uninfected rhesus macaques were used as controls. Uninfected control animals were healthy and euthanized for other unrelated health reasons. All animals were maintained in accordance with the guidelines of the Tulane National Primate Research Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Each animal was initially housed outdoors until assigned onto a research protocol. Representative pieces of the duodenum, ileum/ileocecal junction, and colon were collected immediately after euthanasia, fixed in neutral-buffered formalin, and then paraffin embedded for histological studies.

TABLE 1.

Summary of rhesus macaques evaluated in this study

| Animal | Sex | Age (yr) | Sourcea | dpi | SPF viral status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 05A287 | F | 3.06 | TPC | NAb | B virus+ |

| 03A084 | M | 6.9 | WZ | NA | B virus+ |

| 02A465 | F | 4.36 | TPC | 8 | Negative |

| 02A563 | M | 3.33 | TPC | 8 | Negative |

| 02A459 | M | 7.25 | TPC | 13 | B virus+ |

| 02A462 | M | 8.27 | WZ | 13 | B virus+ |

| 02A560 | M | 3.25 | TPC | 21 | Negative |

| 02A557 | F | 8.15 | WZ | 21 | STLV+ |

TPC, born at Tulane Primate Center; WZ, born at the University of Wisconsin Zoo.

NA, not applicable.

Double-label immunofluorescence.

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues were cut at 5 μm and mounted onto charged slides. Double-label immunofluorescence was performed essentially as described with some modifications (24, 68). Briefly, sections were baked for 1 h at 60°C, deparaffinized in xylenes, and then rehydrated to phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) in graded concentrations of ethanol. Microwave-based antigen retrieval was carried out for 20 min on high power using a citrate-based antigen unmasking solution (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA). Tissues were incubated with the first primary antibody (mouse monoclonal) overnight at 4°C, washed in PBS with fish skin gelatin (PBS/FSG), and then incubated in the dark for 30 min at room temperature with goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies directly conjugated with either Alexa 488 (green) or Alexa 594 (red) fluorochrome (1:1,000; Molecular Probes/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) depending on the combination of antibodies used in the experiment. Sections were washed in PBS/FSG, blocked in protein solution (Dako), and then incubated in the dark for 1 h at room temperature with the second primary antibody (rabbit polyclonal). Slides were washed in PBS/FSG and then incubated in the dark for 30 min at room temperature with goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies directly conjugated with either Alexa 488 (green) or Alexa 594 (red) fluorochrome. Sections were again washed in PBS/FSG, coverslipped with ProLong Gold antifade reagent (Molecular Probes/Invitrogen), and viewed after 1 h of curing. The antibodies and reagents used for immunofluorescent studies are summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Antibodies and reagents used for immunofluorescence studies

| Antibody or reagenta | Source | Specificity | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peripherin | Novocastra | Peripheral nervous tissue | 1:100 |

| IBA 1* | Wako, Inc. | Macrophages, microglia | 1:100 |

| HuC/D | Molecular Probes | Neurons | 1:100 |

| CD3* | Dako | T lymphocytes | 1:100 |

| SIV nef | UK MRC | SIV+ cells, SIV nef | 1:250 |

| Growth-associated protein-43* | Novus Biologicals | GAP-43, peripheral neurons | 1:1,000 |

| Secondary fluorescent antibodies | Molecular Probes | Rabbit/mouse immunoglobulin G | 1:1,000 |

| Secondary biotin antibodies | Vector Labs | Rabbit/mouse immunoglobulin G | 1:200 |

| Streptavidin conjugates | Molecular Probes | Biotin | 1:500 |

*, Rabbit polyclonal antibody.

Fluorescent in situ hybridization.

In situ hybridization for the detection of viral transcripts was performed essentially as described previously (67, 68). Briefly, tissue sections were baked for 1 h at 60°C, removed of wax, and then rehydrated to PBS through graded concentrations of ethanol. Microwave-based antigen retrieval was carried out for 20 min on high power using a citrate-based antigen unmasking solution (Vector Labs) as described above for immunofluorescence studies. Sections were then hybridized overnight with 20 ng of digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled antisense riboprobe at 45°C. Riboprobes for SIV localization were kindly provided by Vanessa Hirsch and Charles Brown, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, Rockville, MD. After hybridization, unbound probes were removed through stringency washings in decreasing concentrations of saline sodium citrate. Bound probes were detected by standard immunological methods using alkaline phosphatase-conjugated sheep anti-DIG antibodies (Molecular Probes/Invitrogen). Fluorescence detection of DIG-labeled riboprobes was performed for 30 min with HNPP/Fast Red TR (Molecular Probes/Invitrogen) as a substrate. Nuclei were counterstained using DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole), and sections were mounted with ProLong Gold antifade reagent (Molecular Probes/Invitrogen) and viewed after 1 h of curing.

Microscopy and image analysis.

Single- or double-label immunofluorescence was performed as described above. Individual fluorescence channels were captured sequentially in black and white by using a Leica DM4000 B (Leica Microsystems) microscope equipped with an Evolution QEi monochrome camera (MediaCybernetics, Silver Spring, MD). ThumbsPlus 6 software (Cerius Software, Inc., Charlotte, NC) was used to assign colors to the individual channels and merge the final composite image. Individual macrophages were not counted because their irregular cytoplasm and cellular processes made it difficult to identify single cells. Instead, we chose to calculate the area occupied by macrophages (IBA1+ red cells) with respect to the area of the ganglia (peripherin+ green cells) by using ImagePro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD). The areas occupied by each cell type were then expressed as the ratio of area IBA1 to peripherin. Since single T cells were easily identified due to their discrete cytoplasm, quantification of individual CD3+ T cells within each ganglion was carried out manually. Duodenum, ileum, and colon were evaluated from each animal when available, and at least five representative ganglia from each level of intestine were evaluated for quantification of macrophages and 10 representative ganglia for quantification of T cells. For quantification of neurons, at least 25 ganglia with one or more HuC/D+ cells were evaluated.

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed for individual animals by using GraphPad Instat 3 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA), and values were expressed as the mean ± the standard error of the mean (SEM) for two animals at each time point. Statistical comparisons using analysis of variance were made between the duodena, ilea, and colons from SIV-infected animals and uninfected controls and among values from different levels of intestine within a given individual. The Pearson correlation coefficient was used to determine the association between the presence of inflammatory cells and changes in the numbers of neurons at each level of intestine. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Characterization of rhesus macaque ENS.

To determine the impact of SIV infection on the structural integrity and cellular composition of the rhesus macaque ENS, we first characterized the ENSs of healthy adult animals. This was accomplished by using a combination of microscopic evaluation of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained tissue sections and routine immunohistochemistry for the detection of peripherin using the standard ABC detection method with DAB as a chromogen (53, 54). Routine histological evaluation of H&E-stained tissue sections revealed that the ENS of the rhesus macaque was composed of two ganglionated plexuses (Fig. 1A). The myenteric plexus (Auerbach's plexus) was evident within the muscularis externa, between the outer longitudinal and inner circular muscle layers, and the submucosal plexus (Meissner's plexus) was evident within the layer of loose connective tissue beneath the mucosa.

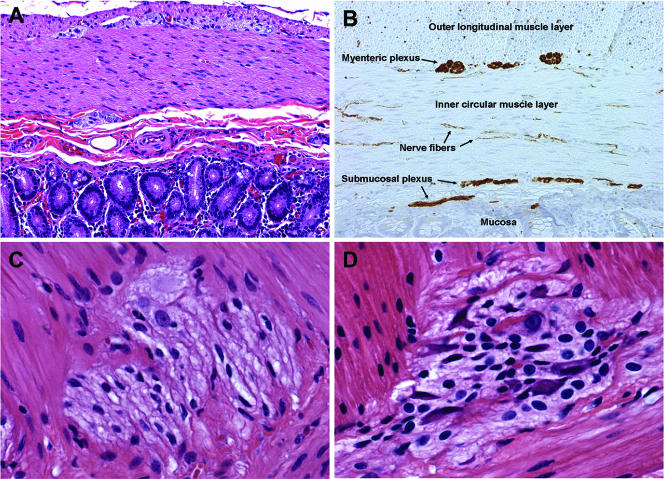

FIG. 1.

(A) H&E staining of duodenum from a healthy macaque. (B) Peripherin immunohistochemistry on duodenum from a healthy macaque demonstrating the myenteric and submucosal plexuses which make up the ENS. Note also the numerous peripherin-positive nerve fibers throughout the muscle layers. (C and D) Higher magnification views of myenteric ganglia from the ileum of a healthy macaque (C) and from an SIV-infected macaque at 21 dpi (D). Note the presence of numerous mononuclear cells in the ganglia from the infected animal compared to the healthy animal.

To examine the structure of the ENS in more detail, we performed routine immunohistochemistry using an anti-peripherin monoclonal antibody. Peripherin is a class III intermediate filament that is expressed exclusively in neurons of peripheral ganglia and their processes and within enteric nerves. Peripherin immunohistochemistry revealed that the submucosal plexus in rhesus macaque intestine was organized in two distinct plexuses (Fig. 1B), similar to what has been reported for other large animal species and humans (62). The outer submucosal plexus is located close to the inner circular muscle layer, and the inner submucosal plexus is located near the muscularis mucosa. The lamina propria, submucosa, and muscular layers were highly innervated, and numerous peripherin-positive nerve fibers were observed coursing throughout these layers (Fig. 1B, arrows).

Effects of SIV Infection on myenteric ganglia.

In the present study we sought to investigate the potential role of the enteric nervous system in the pathogenesis of AIDS enteropathy. We hypothesized that inflammation of the ENS ganglia during primary SIV infection would result in the loss of neurons that would ultimately alter GI function. To begin to address this hypothesis, H&E-stained sections of duodenum, ileum, and colon were evaluated by routine microscopy for evidence of inflammatory changes in the ENS during primary SIV infection. Histological examination identified a prominent enteric ganglionitis of the myenteric plexus in SIV-infected animals (Fig. 1D) compared to uninfected controls (Fig. 1C). Inflammatory mononuclear cells could be seen infiltrating in both peri- and intraganglionic locations. Based on histopathology, our general impression was that ganglia in the small intestine tended to be more severely affected compared to those in the colon and, within a given level of intestine, not all ganglia were uniformly inflamed. In the duodenum, particularly, ganglia located proximal to the pancreas tended to be the most severely effected. Inflamed ganglia often appeared enlarged and edematous, resulting in distortion of the normal ganglionic architecture.

Kinetics and immunophenotype of ENS inflammatory cells.

We next sought to characterize the immunophenotype of inflammatory mononuclear cells within the myenteric plexus and determine temporal changes in ENS immune cell populations from different portions of the GI tract during acute SIV infection. For the evaluation of macrophages, we utilized a polyclonal antibody against ionized calcium-binding adapter 1 (IBA1) that labels CNS microglia and a broad population of macrophages within multiple tissue types in multiple species. This antibody was used in combination with a monoclonal antibody against peripherin to identify neurons of peripheral ganglia and their processes. To quantify macrophages, we determined the relative area occupied by macrophages relative to the area of the ganglia as described in Materials and Methods.

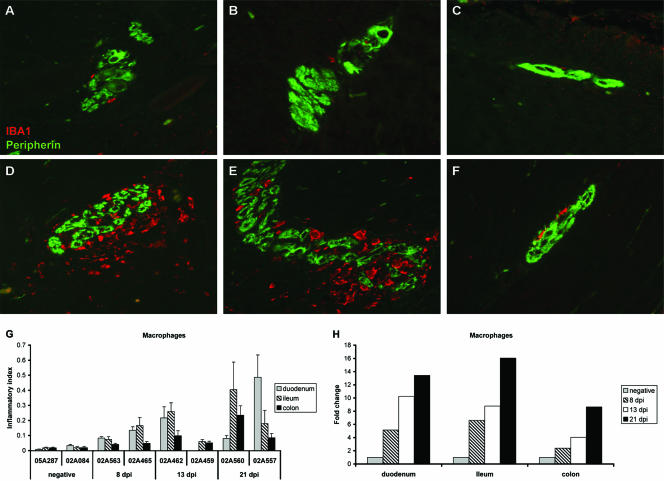

In healthy animals, IBA1+ macrophages were rarely detected in myenteric ganglia from duodenum, ileum, and colon (Fig. 2A, B, and C, respectively), and for each healthy animal, the relative area occupied by macrophages was similar among the different levels of the intestine evaluated (Fig. 2G). During the primary stage of SIV infection, double-label immunofluorescent staining of tissue sections showed increasing numbers of IBA1+ macrophages in ganglia of the myenteric plexus beginning at 8 dpi and continuing through 21 dpi. The extent of macrophage infiltration into the ENS increased with time following SIV infection (Fig. 2G) and, in general, was more severe in ganglia from the duodenum and ileum (Fig. 2D and E) compared to the colon (Fig. 2F) for each animal examined. This resulted in ENS macrophage infiltrates being higher in duodenum and ileum compared to colon in four of the six infected animals evaluated (Fig. 2G). This is in contrast to what we observed in healthy animals in which ENS macrophages were similar among the different levels of the GI tract examined.

FIG. 2.

(A to F) Double-label immunofluorescence staining for peripherin (green) and IBA1 (red) on myenteric ganglia from duodenum, ileum, and colon from a healthy macaque (A, B, and C, respectively) and an SIV-infected macaque at 21 dpi (D, E, and F, respectively). (G) The inflammatory index, i.e., the ratio of the area occupied by macrophages (IBA1) to area of the ganglia (peripherin), was calculated for ganglia at each level of intestine in uninfected macaques and in macaques sacrificed during acute SIV infection. Bars represent mean ± the SEM of at least five representative ganglia per animal at each level of intestine. (H) Fold change in the inflammatory index from uninfected control values for each level of intestine in SIV-infected macaques. Bars represent the mean of the two animals evaluated at each time point.

By as early as 8 dpi, macrophage influx into the ENS was increased markedly (5- to 7-fold) in the small intestine and had doubled in the colons of both animals evaluated at this time point (Fig. 2H). Macrophage infiltration into colonic ganglia continued to double with each successive week after virus infection and by 3 weeks postinfection had increased by nearly ninefold from controls. Similarly, the extent of macrophage infiltration into duodenal and ileal ganglia continued to increase in severity at both 13 and 21 dpi. At 21 dpi, macrophage infiltration in the ENS in both levels of the small intestine was increased 13- to 16-fold compared to that of controls.

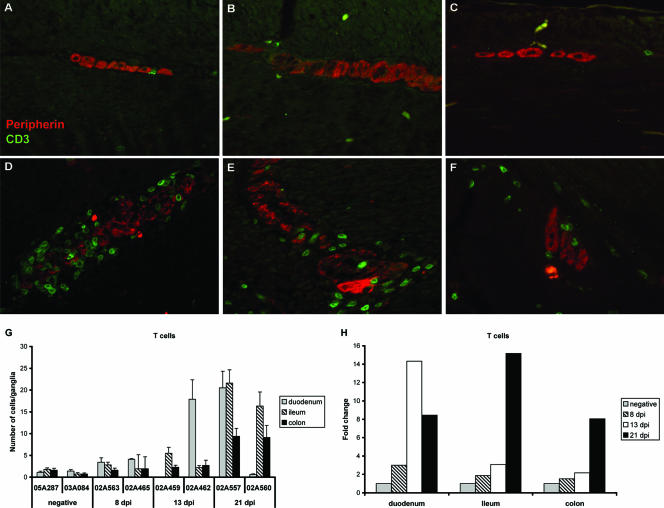

We next performed a series of double-label immunofluorescence studies combining CD3 and peripherin antibodies to evaluate the numbers and distribution of T lymphocytes within the healthy and inflamed ENS during primary SIV infection. Similar to what we observed for the distribution of macrophages in the healthy ENS, CD3+ T cells were rare in myenteric ganglia from the duodena, ilea, and colons of uninfected animals (Fig. 3A, B, and C, respectively). After SIV infection, the pattern of CD3+ T-cell influx into the myenteric plexus was very similar to, although somewhat more variable than, what we observed for macrophages. CD3+ mononuclear cells, morphologically consistent with lymphocytes, demonstrated both peri- and intraganglionic localization within the myenteric plexuses of the duodena, ilea, and colons of infected animals (Fig. 3D, E, and F, respectively). T-cell numbers in the myenteric plexus increased with time after SIV infection and in general were greater in the small intestine compared to the colon (Fig. 3G). ENS T-cell numbers remained relatively stable through 13 dpi in myenteric ganglia from the ileum and colon, increasing slightly by two- to threefold from controls during this period (Fig. 3H). However, by 21 dpi, the numbers of T cells were significantly increased from controls in the ilea and colons from both animals and in the duodenum from one of the two animals. Although the magnitude of T-cell infiltration into the ENS was relatively blunted during the first 2 weeks after virus infection compared to that observed for macrophages, by 21 dpi the magnitude of T-cell inflammation in the myenteric ganglia had reached levels comparable to what we observed for macrophages (Fig. 2H and 3H) in all portions of the GI tract evaluated.

FIG. 3.

(A to F) Double-label immunofluorescence staining for peripherin (red) and CD3 (green) on myenteric ganglia from the duodenum, ileum, and colon from a healthy macaque (A, B, and C, respectively) and an SIV-infected macaque at 21 dpi (D, E, and F, respectively). (G) Mean numbers of CD3+ T cells per ganglia are shown for each level of intestine in uninfected macaques and in macaques sacrificed during acute SIV infection. Bars represent mean ± the SEM of 10 sequential ganglia at each level of intestine. (H) Fold change in T-cell numbers from uninfected controls values for each level of intestine in SIV-infected macaques. Bars represent the mean of the two animals evaluated at each time point.

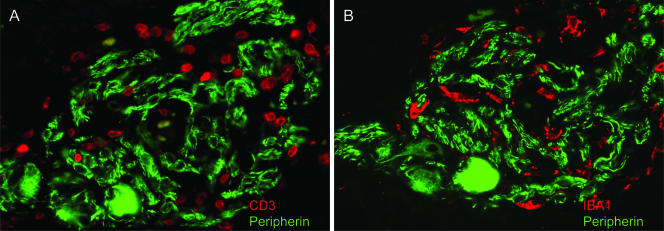

To determine whether T cells and macrophages infiltrated the same ganglia, serial sections of the intestine were stained with peripherin in combination with either CD3 or IBA1. Observations from these experiments demonstrated that CD3+ T cells and IBA1+ macrophages colocalized within the same ganglion (Fig. 4) and, in addition, appear to be represented in approximately equal numbers within the inflamed ganglion. In support of this histological observation, a strong positive statistical correlation was noted between the presence of macrophages and T cells within myenteric ganglia from the duodenum (r2 = 0.90), ileum (r2 = 0.56), and colon (r2 = 0.77), providing evidence that the trafficking into the ENS of these two inflammatory cell types during acute SIV infection is intimately linked, probably due to chemotactic factors produced locally within the ENS microenvironment.

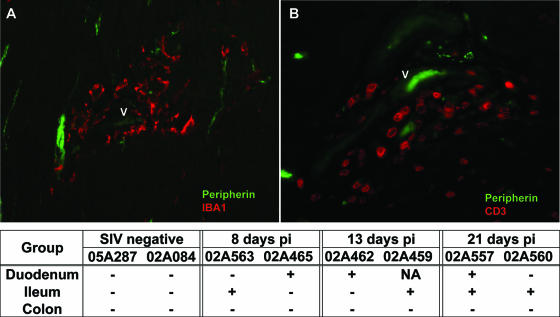

FIG. 4.

(A and B) Double-label immunofluorescence staining for peripherin and either CD3 (A) or IBA1 (B) in myenteric ganglia from the ileum of an SIV-infected macaque at 14 dpi. Inflammatory macrophage and T cells appear to colocalize within the same ganglion in the small intestine.

Other inflammatory changes in the GI tract.

In addition to inflammatory changes associated with the ENS ganglia, discrete foci of inflammation were also observed within the muscularis externa. Intestinal mural lesions were characterized by the accumulation of IBA1+ macrophages (Fig. 5A) and CD3+ T cells (Fig. 5B) within the smooth muscle layers, often in association with neuronal processes (peripherin+ neurites). Mural lesions were often perivascular, suggesting altered trafficking of blood-borne mononuclear cells into the GI tract during acute SIV infection. Lesions within the muscularis were observed in either the duodenum or ileum from each of the six SIV-infected animals but were not detected in the colon of any of these animals (Fig. 5, table). Similar lesions were not evident in any levels of the GI tract of uninfected controls.

FIG. 5.

(A and B) Double-label immunofluorescence staining for peripherin and either CD3 (A) or IBA1 (B) in the duodenum of an SIV-infected macaque at 14 dpi. Note the perivascular localization of inflammatory macrophages and T cells within the smooth muscle layers of the small intestine. “V” denotes a small blood vessel containing one to two autofluorescent red blood cells. The table summarizes the distribution of mural lesions in the GI tract of healthy and SIV-infected macaques. Symbols: +, presence of at least one mural lesion in the representative level of intestine; −, no lesions detected.

Assessment of neuron numbers.

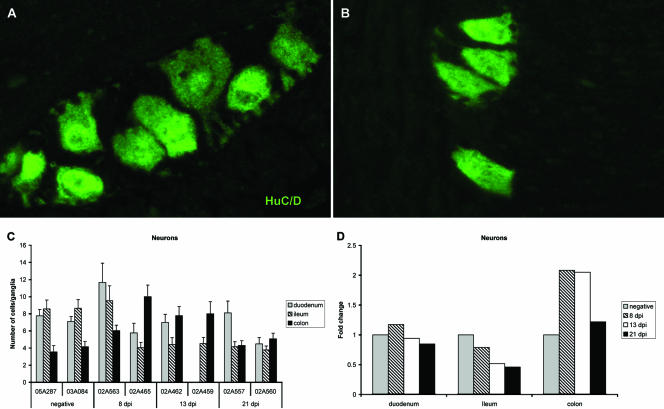

To evaluate the impact of ENS inflammation on the relative health of enteric neurons, immunofluorescence staining was performed on tissue sections using a monoclonal antibody against the human neuronal protein HuC/HuD (HuC/D). HuC/D is a member of the embryonic lethal abnormal visual family of RNA-binding proteins and is expressed specifically in postmitotic neurons. HuC/D is reported to be a pan-neuronal marker in the myenteric plexus (46) which allowed for quantification of neuronal density in myenteric ganglia from different levels of the GI tract prior to and after SIV infection. In healthy animals, the density of neurons in myenteric ganglia was similar in the duodenum and the ileum (seven to eight neurons per ganglia) and was higher than that observed in colonic ganglia (three to four neurons per ganglia) (Fig. 6C). As early as 8 dpi, the neuronal density in myenteric ganglia from the ileum was markedly decreased (four neurons per ganglia) in half of the animals evaluated at this time point. This loss of neurons in the ileal ganglia was sustained at 13 and 21 dpi in all four SIV-infected animals (Fig. 6C). At 8 and 13 dpi, three of the four infected animals that had a 50% reduction in neurons in ileal ganglia also had a concomitant twofold increase in the number of neurons per ganglia more distally in the colon (Fig. 6D). However, at 21 dpi, when macrophage and T-cell influx into colonic ganglia was most severe, the neuronal density in this level of the ENS was reduced by 50% compared to densities observed at 8 and 13 dpi and had returned to preinfection neuronal density. Among all of the animals, there was a strong inverse correlation between T-cell numbers (r2 = −0.53) and macrophages (r2 = −0.70) within the ENS microenvironment and reduced numbers of myenteric neurons. These data suggest a direct cause-and-effect relationship between inflammation and changes in neuronal density; however, it is also possible that the differences that we observed here may be in part due to interanimal variation or that neuronal density in myenteric ganglia may be dependent on the exact level within the small or large intestine from which the sample was obtained.

FIG. 6.

(A and B) Immunofluorescence staining for HuC/D antigen expression on myenteric ganglia from ileum of a healthy macaque (A) and an SIV-infected macaque (B) at 21 dpi. (C) Mean numbers of HuC/D+ neurons per ganglia at each level of intestine in uninfected macaques and in macaques sacrificed during acute SIV infection. Bars represent mean ± the SEM of 25 sequential ganglia. (D) Fold change in neuronal numbers from uninfected controls values for each level of intestine in SIV-infected macaques. Bars represent the mean of the two animals evaluated at each time point.

Localization of SIV within the GI tract.

To begin to understand the role of virus in the pathogenesis of enteric neuropathy caused by SIV infection, we evaluated intestinal tissues for the expression of viral antigen and RNA. Immunofluorescence for the SIV Nef protein was performed to localize viral antigens, and in situ hybridization for viral RNA was performed to localize productively infected cells. SIV-infected mononuclear cells were frequently detected within organized lymphoid nodules in the submucosa and in adjacent mesenteric lymph nodes and were occasionally detected within the mucosa at most time points during primary SIV infection (data not shown). Although we consistently observed numerous inflammatory macrophages and T cells within the ENS at all levels of the GI tract and at all time points after SIV infection as described above, we were not able to find any evidence that these infiltrating cells were infected with SIV as demonstrated by either of these methods (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

GI disease is a frequent complication of HIV infection, with a majority of HIV-infected patients experiencing one or more episodes of diarrhea at some point during the course of their disease. Although the severity of GI symptoms tends to increase with advancing disease, there are numerous reports demonstrating that functional abnormalities of the GI tract are present soon after infection with both HIV and SIV (18, 23, 25, 29, 33). It is widely accepted that HIV and SIV rapidly infect and deplete activated memory CD4+ T cells in the GI tract within days after virus infection; however, it remains unclear how this results in altered GI function and enteropathy in infected individuals. Lentiviruses, including HIV and SIV, are neurotropic viruses which have the ability to infect the nervous system. As a result, these viruses cause a broad spectrum of neurological disease in their infected hosts, including encephalitis and peripheral neuropathy. Since nearly all of the normal functions of the GI tract are under the direct control of the ENS, we speculated that damage to the ENS by HIV/SIV infection might be a contributing factor in the pathogenesis of GI dysfunction and enteropathy with HIV infection. In the present study, we report a previously undescribed neurological complication of SIV infection evident as early as 1 to 2 weeks postinfection; an inflammatory neuropathy of the ENS. Histopathological changes in the ENS were characterized by infiltration of myenteric ganglia by large numbers of macrophages and T cells and by the loss of myenteric neurons. Similar evidence of acute damage to the CNS at these same time points after SIV infection has been reported by multiple groups (10, 14, 19, 28), suggesting a common mechanism of neuropathogenesis for SIV in both the central and the enteric nervous systems. These observations provide evidence that novel mechanisms, such as ENS dysfunction, are involved in the pathogenesis of HIV enteropathy.

In the present study, we sought to systematically evaluate changes in the structure and cellular composition of myenteric ganglia from multiple levels of the GI tract during the first 3 weeks after SIV infection. By evaluating changes in the ENS very early during the course of SIV infection, prior to the onset of immunosuppression, we were able to avoid any potential confounding effects of opportunistic enteric pathogens on the development of ENS pathology. Using multilabel immunofluorescence, we provide quantitative morphological evidence demonstrating for the first time an inflammatory neuropathy within multiple levels of the GI tract after acute infection with SIV. ENS inflammation was progressive, increasing in severity with time after SIV infection, and was most extensive in ganglia from the duodenum and ileum rather than the colon. We found that large numbers of macrophages infiltrated myenteric ganglia initially, increasing by as much as 15-fold from control animals by 3 weeks postinfection. These changes represented a series of successive doublings of macrophages in myenteric ganglia with each subsequent week after SIV infection. Although the pattern and magnitude of T-cell trafficking into the ENS was somewhat more variable than that seen for macrophages, by 3 weeks postinfection the relative increases in cell numbers observed for both cell types were comparable. Detailed histological evaluation of GI tissues revealed that many of the ENS inflammatory cells were localized around small blood vessels, suggesting a hematogenous origin for these cells. It is likely that macrophages infiltrate the ENS initially, producing chemotactic factors that then attract T cells and additional macrophages into the ganglia as the course of disease progresses. It is not clear why inflammatory cells initially traffic into the ENS, but the reasons are likely linked to the depletion of mucosal T cells by HIV/SIV infection, marked immune activation, and the resultant disruption in the interactions between the nervous and immune systems within the GI tract (8, 57). Furthermore, the similar increase in macrophages observed in the CNS at the same time points suggests the possibility of common mechanisms of neuropathogenesis.

Despite the abundance of inflammatory cells evident within the ENS, we were not able to find any evidence that these cells were infected with SIV as determined by immunofluorescence for Nef protein and in situ hybridization for viral RNA. Infected cells were, however, often present elsewhere in the tissue. By examining myenteric ganglia within multiple levels of the GI tract in each of the six infected animals during acute infection, we have shown that despite widespread systemic replication of SIV in the lymphoid compartment of intestinal tissues, there was a paucity of viral RNA+/antigen+ cells in the ENS of all the GI tissues evaluated. Therefore, the ENS is not a direct early target for virus infection which is seeded with infected cells during acute infection. This is in contrast to the neuropathogenesis of HIV/SIV in the CNS, in which virus crosses the blood-brain barrier early after infection and can be detected in the neuropil and cerebrospinal fluid by 7 to 14 days after infection (27, 40, 59, 66). As a consequence, the brain is generally considered to be a reservoir of latent HIV and SIV infection (1, 7, 51). Although we have not examined the ENS for evidence of latent SIV infection, it is possible that along the entire length of the GI tract a small proportion of ENS inflammatory cells might be provirus positive during acute infection and clinical latency. These observations support the thesis that local immunological dysfunction within the ENS and its downstream effects are the consequences of systemic virus replication and its altered immunopathological consequences rather than the direct effects of local virus replication within the ENS. Similarly, HIV sensory neuropathy and AIDS dementia are more closely correlated with the amount of macrophage infiltration within nerves and brain than with viral loads within these tissues (4, 13, 41, 65), suggesting a common mechanism of neuropathogenesis for HIV/SIV in the central, peripheral, and enteric nervous systems.

The histopathological changes that we describe here in myenteric ganglia of rhesus macaques infected with SIV are quite similar to what has been reported with distal sensory neuropathy in people with HIV/AIDS (36). In people with peripheral neuropathy, it has been postulated that the aberrant inflammatory response in dorsal root ganglia leads to changes in sodium channels on neurons, resulting in neuronal dysfunction, injury, and loss of epidermal innervation in the skin (20, 47, 64). It is possible that the inflammation and damage to enteric nerves that we observed here with SIV infection results in a similar sequence of events, culminating in the degeneration of enteric nerve fibers, retraction of neuronal processes, and loss of intestinal mucosal innervation, thereby contributing to GI dysfunction and enteropathy with HIV/SIV infection. In support of this hypothesis, a reduction of axonal density in lamina propria has been reported in the jejuna of HIV-infected patients without secondary opportunistic enteropathogen infections (2, 15, 35). In these studies, asymptomatic HIV-infected individuals had similar levels of axonal damage in the jejunum compared to symptomatic patients, suggesting that ENS damage with HIV infection, similar to what we report here with SIV infection, is an early event in the course of disease.

Although we have observed mild to moderate inflammatory changes in myenteric ganglia within all levels of the GI tract examined in the present study, only neurons within the ileum were lost after SIV infection. Neurons within duodenal ganglia were quite resistant to the neurotoxic effects of inflammation, with cell numbers remaining relatively stable throughout the course of primary SIV infection despite abundant influx of both macrophages and T lymphocytes. It is likely however, that the inflammation we observed in myenteric ganglia in the other levels of the GI tract with SIV infection results in substantial neuronal injury and dysfunction which may also contribute to the development of enteropathy. In addition, while myenteric ganglionitis in ileum was progressive during the first few weeks after SIV infection, neuronal loss in ileal ganglia was not. Rather, there appeared to be an all-or-nothing response by ileal neurons to the toxic effects of inflammation, and once a minimum threshold of inflammatory cells had accumulated within the ganglia, a subset of sensitive neurons (>50% of the total in seven of eight infected animals) was lost. These observations probably reflect differences in neurochemical coding among enteric neurons in the different levels of the GI tract of the rhesus macaque, as has been extensively described for the guinea pig (5, 11, 31, 32, 48), and their distinct responses under pathophysiological conditions. Given the absence of SIV-infected cells within the ENS, the neuronal loss that we observe here during acute SIV infection is most likely the result of indirect immune-mediated mechanisms involving neurotoxins produced locally by inflammatory cells and not due to direct viral neurotoxicity.

In summary, the changes that we report here in the ENS using an SIV-infected macaque model of HIV infection represent an additional neurological complication of HIV/SIV infection: an inflammatory neuropathy of myenteric ganglia. Myenteric ganglionitis within multiple levels of the GI tract and the associated neuronal injury and loss likely plays a key role in the pathogenesis of GI dysfunction and enteropathy commonly seen in people and macaques infected with HIV/SIV, respectively. This novel model of HIV enteropathy offers further insight into additional neuropathogenic mechanisms of HIV infection and identifies the ENS as a unique target for therapeutic intervention in the treatment of HIV-associated GI disease. The similarities in pathology among central, peripheral, and enteric nervous system diseases observed after HIV and SIV infections suggest a common mechanism of neuropathogenesis among lentiviruses within the nervous system as a whole.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jessica Clark, Lindsay Jarvis, and Erica D'Spain for technical assistance.

This study was supported by grants RR20159 and RR00164 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 28 March 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barber, S. A., D. S. Herbst, B. T. Bullock, L. Gama, and J. E. Clements. 2004. Innate immune responses and control of acute simian immunodeficiency virus replication in the central nervous system. J. Neurovirol. 10(Suppl. 1):15-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Batman, P. A., A. R. Miller, P. M. Sedgwick, and G. E. Griffin. 1991. Autonomic denervation in jejunal mucosa of homosexual men infected with HIV. AIDS 5:1247-1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bjarnason, I., D. R. Sharpstone, N. Francis, A. Marker, C. Taylor, M. Barrett, A. Macpherson, C. Baldwin, I. S. Menzies, R. C. Crane, T. Smith, A. Pozniak, and B. G. Gazzard. 1996. Intestinal inflammation, ileal structure and function in HIV. AIDS 10:1385-1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boven, L. A., J. Middel, J. Verhoef, C. J. De Groot, and H. S. Nottet. 2000. Monocyte infiltration is highly associated with loss of the tight junction protein zonula occludens in HIV-1-associated dementia. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 26:356-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brookes, S. J. 2001. Classes of enteric nerve cells in the guinea-pig small intestine. Anat. Rec. 262:58-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ciarlet, M., and M. K. Estes. 2001. Interactions between rotavirus and gastrointestinal cells. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 4:435-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clements, J. E., T. Babas, J. L. Mankowski, K. Suryanarayana, M. Piatak, Jr., P. M. Tarwater, J. D. Lifson, and M. C. Zink. 2002. The central nervous system as a reservoir for simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV): steady-state levels of SIV DNA in brain from acute through asymptomatic infection. J. Infect. Dis. 186:905-913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fiocchi, C. 1997. Intestinal inflammation: a complex interplay of immune and nonimmune cell interactions. Am. J. Physiol. 273:G769-G775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fliers, E., H. P. Sauerwein, J. A. Romijn, P. Reiss, M. van der Valk, A. Kalsbeek, F. Kreier, and R. M. Buijs. 2003. HIV-associated adipose redistribution syndrome as a selective autonomic neuropathy. Lancet 362:1758-1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fuller, R. A., S. V. Westmoreland, E. Ratai, J. B. Greco, J. P. Kim, M. R. Lentz, J. He, P. K. Sehgal, E. Masliah, E. Halpern, A. A. Lackner, and R. G. Gonzalez. 2004. A prospective longitudinal in vivo 1H MR spectroscopy study of the SIV/macaque model of neuroAIDS. BMC Neurosci. 5:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furness, J. B., H. M. Young, S. Pompolo, J. C. Bornstein, W. A. Kunze, and K. McConalogue. 1995. Plurichemical transmission and chemical coding of neurons in the digestive tract. Gastroenterology 108:554-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gartner, S. 2000. HIV infection and dementia. Science 287:602-604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glass, J. D., H. Fedor, S. L. Wesselingh, and J. C. McArthur. 1995. Immunocytochemical quantitation of human immunodeficiency virus in the brain: correlations with dementia. Ann. Neurol. 38:755-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez, R. G., L. L. Cheng, S. V. Westmoreland, K. E. Sakaie, L. R. Becerra, P. L. Lee, E. Masliah, and A. A. Lackner. 2000. Early brain injury in the SIV-macaque model of AIDS. AIDS 14:2841-2849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griffin, G. E., A. Miller, P. Batman, S. M. Forster, A. J. Pinching, J. R. Harris, and M. M. Mathan. 1988. Damage to jejunal intrinsic autonomic nerves in HIV infection. AIDS 2:379-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansen, M. B. 2003. The enteric nervous system II: gastrointestinal functions. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 92:249-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heise, C., C. J. Miller, A. Lackner, and S. Dandekar. 1994. Primary acute simian immunodeficiency virus infection of intestinal lymphoid tissue is associated with gastrointestinal dysfunction. J. Infect. Dis. 169:1116-1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heise, C., P. Vogel, C. J. Miller, C. H. Halsted, and S. Dandekar. 1993. Simian immunodeficiency virus infection of the gastrointestinal tract of rhesus macaques: functional, pathological, and morphological changes. Am. J. Pathol. 142:1759-1771. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helke, K. L., S. E. Queen, P. M. Tarwater, J. Turchan-Cholewo, A. Nath, M. C. Zink, D. N. Irani, and J. L. Mankowski. 2005. 14-3-3 protein in CSF: an early predictor of SIV CNS disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 64:202-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones, G., Y. Zhu, C. Silva, S. Tsutsui, C. A. Pardo, O. T. Keppler, J. C. McArthur, and C. Power. 2005. Peripheral nerve-derived HIV-1 is predominantly CCR5-dependent and causes neuronal degeneration and neuroinflammation. Virology 334:178-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaul, M., G. A. Garden, and S. A. Lipton. 2001. Pathways to neuronal injury and apoptosis in HIV-associated dementia. Nature 410:988-994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keating, J., I. Bjarnason, S. Somasundaram, A. Macpherson, N. Francis, A. B. Price, D. Sharpstone, J. Smithson, I. S. Menzies, and B. G. Gazzard. 1995. Intestinal absorptive capacity, intestinal permeability and jejunal histology in HIV and their relation to diarrhoea. Gut 37:623-629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kewenig, S., T. Schneider, K. Hohloch, K. Lampe-Dreyer, R. Ullrich, N. Stolte, C. Stahl-Hennig, F. J. Kaup, A. Stallmach, and M. Zeitz. 1999. Rapid mucosal CD4+ T-cell depletion and enteropathy in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus macaques. Gastroenterology 116:1115-1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klein, R. S., K. C. Williams, X. Alvarez-Hernandez, S. Westmoreland, T. Force, A. A. Lackner, and A. D. Luster. 1999. Chemokine receptor expression and signaling in macaque and human fetal neurons and astrocytes: implications for the neuropathogenesis of AIDS. J. Immunol. 163:1636-1646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knox, T. A., D. Spiegelman, S. C. Skinner, and S. Gorbach. 2000. Diarrhea and abnormalities of gastrointestinal function in a cohort of men and women with HIV infection. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 95:3482-3489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kordasti, S., H. Sjovall, O. Lundgren, and L. Svensson. 2004. Serotonin and vasoactive intestinal peptide antagonists attenuate rotavirus diarrhoea. Gut 53:952-957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lane, J. H., V. G. Sasseville, M. O. Smith, P. Vogel, D. R. Pauley, M. P. Heyes, and A. A. Lackner. 1996. Neuroinvasion by simian immunodeficiency virus coincides with increased numbers of perivascular macrophages/microglia and intrathecal immune activation. J. Neurovirol. 2:423-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lentz, M. R., J. P. Kim, S. V. Westmoreland, J. B. Greco, R. A. Fuller, E. M. Ratai, J. He, P. K. Sehgal, E. F. Halpern, A. A. Lackner, E. Masliah, and R. G. Gonzalez. 2005. Quantitative neuropathologic correlates of changes in ratio of N-acetylaspartate to creatine in macaque brain. Radiology 235:461-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lim, S. G., I. S. Menzies, C. A. Lee, M. A. Johnson, and R. E. Pounder. 1993. Intestinal permeability and function in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus: a comparison with coeliac disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 28:573-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lima, A. A., T. M. Silva, A. M. Gifoni, L. J. Barrett, I. T. McAuliffe, Y. Bao, J. W. Fox, D. P. Fedorko, and R. L. Guerrant. 1997. Mucosal injury and disruption of intestinal barrier function in HIV-infected individuals with or without diarrhea and cryptosporidiosis in northeast Brazil. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 92:1861-1866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lomax, A. E., P. P. Bertrand, and J. B. Furness. 1998. Identification of the populations of enteric neurons that have NK1 tachykinin receptors in the guinea-pig small intestine. Cell Tissue Res. 294:27-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lomax, A. E., and J. B. Furness. 2000. Neurochemical classification of enteric neurons in the guinea-pig distal colon. Cell Tissue Res. 302:59-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luangjaru, S., K. Ruxrungtham, N. Wisedopas, and V. Mahachai. 2003. d-Xylose absorption in non-chronic diarrhea AIDS patients with the wasting syndrome. J. Med. Assoc. Thai 86(Suppl. 2):S477-S483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lundgren, O., A. T. Peregrin, K. Persson, S. Kordasti, I. Uhnoo, and L. Svensson. 2000. Role of the enteric nervous system in the fluid and electrolyte secretion of rotavirus diarrhea. Science 287:491-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mathan, M. M., G. E. Griffin, A. Miller, P. Batman, S. Forster, A. Pinching, and W. Harris. 1990. Ultrastructure of the jejunal mucosa in human immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Pathol. 161:119-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McArthur, J. C., B. J. Brew, and A. Nath. 2005. Neurological complications of HIV infection. Lancet Neurol. 4:543-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mourad, F. H., and C. F. Nassar. 2000. Effect of vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP) antagonism on rat jejunal fluid and electrolyte secretion induced by cholera and Escherichia coli enterotoxins. Gut 47:382-386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Navia, B. A., B. D. Jordan, and R. W. Price. 1986. The AIDS dementia complex. I. Clinical features. Ann. Neurol. 19:517-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Obinna, F. C., G. Cook, T. Beale, S. Dave, D. Cunningham, S. C. Fleming, E. Claydon, J. W. Harris, and M. S. Kapembwa. 1995. Comparative assessment of small intestinal and colonic permeability in HIV-infected homosexual men. AIDS 9:1009-1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palmer, D. L., B. L. Hjelle, C. A. Wiley, S. Allen, W. Wachsman, R. G. Mills, L. E. Davis, and T. L. Merlin. 1994. HIV-1 infection despite immediate combination antiviral therapy after infusion of contaminated white cells. Am. J. Med. 97:289-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pardo, C. A., J. C. McArthur, and J. W. Griffin. 2001. HIV neuropathy: insights in the pathology of HIV peripheral nerve disease. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 6:21-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peregrin, A. T., H. Ahlman, M. Jodal, and O. Lundgren. 1999. Involvement of serotonin and calcium channels in the intestinal fluid secretion evoked by bile salt and cholera toxin. Br. J. Pharmacol. 127:887-894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pernet, P., D. Vittecoq, A. Kodjo, M. H. Randrianarisolo, L. Dumitrescu, H. Blondon, J. F. Bergmann, J. Giboudeau, and C. Aussel. 1999. Intestinal absorption and permeability in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 34:29-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pfeiffer, R. F. 2003. Gastrointestinal dysfunction in Parkinson's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2:107-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pfeiffer, R. F. 1998. Gastrointestinal dysfunction in Parkinson's disease. Clin. Neurosci. 5:136-146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Phillips, R. J., S. L. Hargrave, B. S. Rhodes, D. A. Zopf, and T. L. Powley. 2004. Quantification of neurons in the myenteric plexus: an evaluation of putative pan-neuronal markers. J. Neurosci. Methods 133:99-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Polydefkis, M., C. T. Yiannoutsos, B. A. Cohen, H. Hollander, G. Schifitto, D. B. Clifford, D. M. Simpson, D. Katzenstein, S. Shriver, P. Hauer, A. Brown, A. B. Haidich, L. Moo, and J. C. McArthur. 2002. Reduced intraepidermal nerve fiber density in HIV-associated sensory neuropathy. Neurology 58:115-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Portbury, A. L., K. McConalogue, J. B. Furness, and H. M. Young. 1995. Distribution of pituitary adenylyl cyclase activating peptide (PACAP) immunoreactivity in neurons of the guinea-pig digestive tract and their projections in the ileum and colon. Cell Tissue Res. 279:385-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Przuntek, H., T. Muller, and P. Riederer. 2004. Diagnostic staging of Parkinson's disease: conceptual aspects. J. Neural Transm. 111:201-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rho, M. B., S. Wesselingh, J. D. Glass, J. C. McArthur, S. Choi, J. Griffin, and W. R. Tyor. 1995. A potential role for interferon-alpha in the pathogenesis of HIV-associated dementia. Brain Behav. Immun. 9:366-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roberts, E. S., E. M. Burudi, C. Flynn, L. J. Madden, K. L. Roinick, D. D. Watry, M. A. Zandonatti, M. A. Taffe, and H. S. Fox. 2004. Acute SIV infection of the brain leads to upregulation of IL6 and interferon-regulated genes: expression patterns throughout disease progression and impact on neuroAIDS. J. Neuroimmunol. 157:81-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rogstad, K. E., R. Shah, G. Tesfaladet, M. Abdullah, and I. Ahmed-Jushuf. 1999. Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy in HIV-infected patients. Sex. Transm. Infect. 75:264-267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sasseville, V. G., J. H. Lane, D. Walsh, D. J. Ringler, and A. A. Lackner. 1995. VCAM-1 expression and leukocyte trafficking to the CNS occur early in infection with pathogenic isolates of SIV. J. Med. Primatol. 24:123-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sasseville, V. G., M. M. Smith, C. R. Mackay, D. R. Pauley, K. G. Mansfield, D. J. Ringler, and A. A. Lackner. 1996. Chemokine expression in simian immunodeficiency virus-induced AIDS encephalitis. Am. J. Pathol. 149:1459-1467. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schifitto, G., M. P. McDermott, J. C. McArthur, K. Marder, N. Sacktor, D. R. McClernon, K. Conant, B. Cohen, L. G. Epstein, and K. Kieburtz. 2005. Markers of immune activation and viral load in HIV-associated sensory neuropathy. Neurology 64:842-848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sharpstone, D., P. Neild, R. Crane, C. Taylor, C. Hodgson, R. Sherwood, B. Gazzard, and I. Bjarnason. 1999. Small intestinal transit, absorption, and permeability in patients with AIDS with and without diarrhoea. Gut 45:70-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shepherd, A. J., J. E. Downing, and J. A. Miyan. 2005. Without nerves, immunology remains incomplete-in vivo veritas. Immunology 116:145-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Singaram, C., W. Ashraf, E. A. Gaumnitz, C. Torbey, A. Sengupta, R. Pfeiffer, and E. M. Quigley. 1995. Dopaminergic defect of enteric nervous system in Parkinson's disease patients with chronic constipation. Lancet 346:861-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smith, M. O., M. P. Heyes, and A. A. Lackner. 1995. Early intrathecal events in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) infected with pathogenic or nonpathogenic molecular clones of simian immunodeficiency virus. Lab. Investig. 72:547-558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stone, J. D., C. C. Heise, C. J. Miller, C. H. Halsted, and S. Dandekar. 1994. Development of malabsorption and nutritional complications in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus macaques. AIDS 8:1245-1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tepper, R. E., D. Simon, L. J. Brandt, R. Nutovits, and M. J. Lee. 1994. Intestinal permeability in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 89:878-882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Timmermans, J. P., J. Hens, and D. Adriaensen. 2001. Outer submucous plexus: an intrinsic nerve network involved in both secretory and motility processes in the intestine of large mammals and humans. Anat. Rec. 262:71-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tyor, W. R., S. L. Wesselingh, J. W. Griffin, J. C. McArthur, and D. E. Griffin. 1995. Unifying hypothesis for the pathogenesis of HIV-associated dementia complex, vacuolar myelopathy, and sensory neuropathy. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. Hum. Retrovirol. 9:379-388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Waxman, S. G. 1999. The molecular pathophysiology of pain: abnormal expression of sodium channel genes and its contributions to hyperexcitability of primary sensory neurons. Pain 1999(Suppl. 6):S133-S140. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Weis, S., B. Neuhaus, and P. Mehraein. 1994. Activation of microglia in HIV-1 infected brains is not dependent on the presence of HIV-1 antigens. Neuroreport 5:1514-1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Westmoreland, S. V., K. C. Williams, M. A. Simon, M. E. Bahn, A. E. Rullkoetter, M. W. Elliott, C. D. deBakker, H. L. Knight, and A. A. Lackner. 1999. Neuropathogenesis of simian immunodeficiency virus in neonatal rhesus macaques. Am. J. Pathol. 155:1217-1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Williams, K., A. Schwartz, S. Corey, M. Orandle, W. Kennedy, B. Thompson, X. Alvarez, C. Brown, S. Gartner, and A. Lackner. 2002. Proliferating cellular nuclear antigen expression as a marker of perivascular macrophages in simian immunodeficiency virus encephalitis. Am. J. Pathol. 161:575-585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Williams, K. C., S. Corey, S. V. Westmoreland, D. Pauley, H. Knight, C. deBakker, X. Alvarez, and A. A. Lackner. 2001. Perivascular macrophages are the primary cell type productively infected by simian immunodeficiency virus in the brains of macaques: implications for the neuropathogenesis of AIDS. J. Exp. Med. 193:905-915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]