Abstract

We performed live cell visualization assays to directly assess the interaction between competing adeno-associated virus (AAV) and herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) DNA replication. Our studies reveal the formation of separate AAV and HSV-1 replication compartments and the inhibition of HSV-1 replication compartment formation in the presence of AAV. AAV Rep is recruited into AAV replication compartments but not into those of HSV-1, while the single-stranded DNA-binding protein HSV-1 ICP8 is recruited into both AAV and HSV-1 replication compartments, although with differential staining patterns. Slot blot analysis of coinfected cells revealed a dose-dependent inhibition of HSV-1 DNA replication by wild-type AAV but not by rep-negative recombinant AAV. Consistent with this, Western blot analysis indicated that wild-type AAV affects the levels of the HSV-1 immediate-early protein ICP4 and the early protein ICP8 only modestly but strongly inhibits the accumulation of the late proteins VP16 and gC. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the presence of Rep in the absence of AAV DNA replication is sufficient for the inhibition of HSV-1. In particular, Rep68/78 proteins severely inhibit the formation of mature HSV-1 replication compartments and lead to the accumulation of ICP8 at sites of cellular DNA synthesis, a phenomenon previously observed in the presence of viral polymerase inhibitors. Taken together, our results suggest that AAV and HSV-1 replicate in separate compartments and that AAV Rep inhibits HSV-1 at the level of DNA replication.

Adeno-associated virus (AAV), a nonpathogenic human parvovirus, is a small, nonenveloped DNA virus with a single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) genome of 4,680 nucleotides (nt). The AAV genome consists of two open reading frames, carrying the rep and the cap genes, flanked by two 145-nt inverted terminal repeats (ITRs). The rep gene encodes the nonstructural replication proteins (Rep), while the cap gene encodes the capsid proteins forming the icosahedral capsid. AAV has a unique, biphasic life cycle that is characterized by productive infection in the presence of helper viruses, such as adenovirus (Ad) or a herpesvirus, and latent infection, which occurs in the absence of a helper virus (reviewed in reference 32). The AAV type 2 (AAV2) genome, for instance, can site-specifically integrate into human chromosome 19 at position 19q13.4, a locus that is termed AAVS1. In addition, AAV, and in particular rep-negative recombinant AAV (rAAV) gene delivery vectors, can also maintain a latent infection by episomal maintenance of circularized genomes (reviewed in reference 28). The AAV Rep proteins are multifunctional regulatory proteins essential for viral DNA replication, regulation of gene expression, site-specific integration, and packaging of viral genomes into capsids (reviewed in reference 32). Infection of a cell with AAV has pleiotropic, mostly inhibitory effects on both the host cell and the helper virus. For instance, cell cycle arrest can be induced by either AAV Rep (3, 35) or single-stranded AAV DNA (22, 33), whereas AAV Rep was demonstrated to inhibit replication of a number of heterologous viruses (reviewed in reference 15).

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), on the other hand, is a large, enveloped DNA virus and an important human pathogen. The HSV-1 genome consists of a 152-kb double-stranded DNA and encodes approximately 80 gene products, which are expressed in a temporally regulated cascade. In particular, HSV-1 genes are classified as immediate-early (IE or α), early (β), and late (γ) genes. The first genes to be expressed upon infection are the IE genes, encoding several transactivator proteins, which in turn initiate transcription of the early and some late genes, called leaky late or γ1 genes. Early gene products comprise the viral DNA replication factors initiating viral DNA synthesis, which in turn stimulates expression of the leaky late (γ1) and true late (γ2) genes. The latter encode mainly structural virion proteins. The life cycle of HSV-1 is characterized by productive (lytic) replication in epithelial cells of the mucosa and life-long latent infection in the corresponding sensory neurons, from which HSV-1 can sporadically reactivate (reviewed in reference 42). HSV-1 and HSV-2 are helper viruses for AAV replication (4), with the helicase-primase complex (encoded by UL5, UL8, and UL52) and the ssDNA-binding protein ICP8 (encoded by UL29) acting as the minimal helper factors required for productive AAV replication (50). Notably, enzymatic function of the helicase-primase complex is not required for the helper activity; rather, the helicase-primase complex appears to be required for correct subnuclear localization of ICP8, suggesting that ICP8 is the key helper factor (36, 40).

On several occasions, AAV was suggested to cause inhibition of HSV-1 replication. In particular, coinfection with AAV inhibited replication of HSV-1 in simian virus 40-transformed hamster cells (1). A subsequent study reported the inhibition of HSV-1 oriS-dependent replication by cotransfection of AAV rep-expressing plasmids (18). More recently, we and others demonstrated that the rep gene present in HSV/AAV hybrid amplicon vectors inhibited vector replication and/or packaging, resulting in up to 2,000-fold reduced titers of packaged vector stocks (20, 48). However, only a little is known about the molecular mechanisms of AAV-mediated inhibition of HSV-1 replication.

Recent studies have addressed the interaction between AAV and the helper virus HSV-1. In a first study, Rep was shown to colocalize with ICP8 in AAV-HSV-1-coinfected cells, but not when rep was expressed from a recombinant HSV-1 in the absence of AAV DNA. The same study also demonstrated a direct interaction of Rep with ICP8, which was enhanced upon the addition of ssDNA (19). A second study also showed a partial overlap of Rep with ICP8 when cells were either coinfected with AAV and HSV-1 or cotransfected with an AAV plasmid and the minimal HSV-1 helper factors. The same study also confirmed the direct binding of Rep to ICP8 and, in addition, showed that this interaction enhanced Rep binding to and nicking of the AAV ITRs (40). However, these studies did not directly assess the relative subnuclear distributions of replicating AAV and HSV-1 DNAs.

In the present study, we directly covisualize DNA replication of AAV and HSV-1 in live cells. The assays reveal the formation of separate AAV and HSV-1 replication compartments (RCs), with recruitment of Rep into AAV but not into HSV-1 RCs. HSV-1 ICP8 accumulates at both AAV and HSV-1 RCs, although with differential staining patterns. However, the formation of HSV-1 RCs is markedly inhibited in the presence of AAV. Consistent with this, we show that replication of HSV-1 is inhibited by coinfection with wild-type (wt) AAV2, but not with a rep-negative rAAV, and that this inhibition occurs at the level of HSV-1 DNA replication while only modestly affecting HSV-1 IE and early gene expression. Finally, we demonstrate that the mere presence of AAV Rep proteins in the absence of AAV DNA replication is sufficient for inhibition of HSV-1. In particular, Rep68/78 proteins severely inhibit the formation of mature HSV-1 RCs and lead to the accumulation of ICP8 at sites of cellular DNA synthesis, a phenomenon observed previously in the presence of viral polymerase inhibitors (27, 47).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses. (i) Cells.

HeLa, Vero, and Vero 2-2 cells (37) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units/ml penicillin G, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 0.25 μg/ml amphotericin B. For culture of Vero 2-2 cells, 500 μg/ml G418 was included in the medium.

(ii) HSV-1.

HSV-1 strain F was grown and titrated in Vero 2-2 cells. The recombinant HSV-1 viruses vECFP-ICP4 and vEYFP-ICP4, expressing enhanced cyan fluorescent protein (ECFP) and enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) fused to the N terminus of ICP4 from the native IE3 promoter (11), were kindly provided by R. D. Everett (MRC Virology Unit, Glasgow, United Kingdom).

(iii) AAV.

wt AAV2 and rAAV2-GFP were produced by using the two-plasmid protocol described by Zolotukhin and colleagues (54), with the following modifications. 293T cells (ATCC) were grown in triple flasks for 24 h (DMEM plus 10% FBS) prior to adding the calcium phosphate precipitate. rAAV2-GFP was generated using plasmids pTRUF11 (obtained from S. Zolotukhin, University of Florida, FL) and pDG (17), while wt AAV2 was generated using pAV2 (24) instead of pTRUF11. After 72 h, the virus was purified from Benzonase-treated crude cell lysates over an iodixanol density gradient (Optiprep; Greiner Bio-One), followed by heparin-agarose type I affinity chromatography (Sigma). Finally, viruses were concentrated and formulated in lactated Ringer's solution (Baxter), using Vivaspin 20 50,000-molecular-weight-cutoff centrifugal concentrators (Vivascience), and then stored at −80°C. The biochemical purity of the virus stocks (>95%) was assessed by silver staining after electrophoresis. rAAV2 transducing unit (TU) titers were determined as follows: C12 cells (6) were coinfected with serial dilutions of rAAV-GFP vector stocks and wt Ad5 (multiplicity of infection [MOI] of 20), followed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis after 42 h. wt AAV2 infectious unit (IU) titers were determined on HeLa cells coinfected with wt Ad (MOI, 20). After 42 h, cells were transferred to nylon membranes (Millipore), followed by hybridization using a 32P-radiolabeled AAV2 rep probe.

Antibodies. (i) Primary antibodies.

The anti-HSV-1 ICP8 monoclonal antibody (MAb) 7381 was kindly provided by R. D. Everett (MRC Virology Unit, Glasgow, United Kingdom). The rabbit anti-HSV-1 ICP8 serum 4-83 (23) was a kind gift of D. M. Knipe (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). Anti-HSV-1 VP16 MAb LP1 (29) was kindly donated by A. Minson and H. Browne (University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom). Rabbit anti-HSV-1 gC serum R47 (7) was a kind gift of G. H. Cohen and R. J. Eisenberg (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA). A rabbit anti-AAV Rep serum (45) was kindly provided by J. P. Trempe (Medical University of Ohio, Toledo, OH). Anti-HSV-1 ICP8 MAb (clone 10A3) was purchased from Abcam, anti-HSV-1 ICP4 MAb was purchased from Advanced Biotechnologies, anti-AAV Rep MAb (clone 303.9) was purchased from Fitzgerald Industries International, anti-green fluorescent protein (anti-GFP) MAb (JL-8) was purchased from Clontech, anti-bromodeoxyuridine (anti-BrdU) MAb (clone BMC 9318) was purchased from Roche, and rabbit anti-actin polyclonal antibody (H300) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

(ii) Secondary antibodies.

Goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G heavy plus light chains [IgG(H+L)]-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and goat anti-rabbit IgG(H+L)-horseradish peroxidase were purchased from Southern Biotech, goat anti-mouse IgG(H+L)-Alexa Fluor 594 (AF594) was purchased from Molecular Probes, and rabbit anti-mouse IgG (whole molecule)-peroxidase was purchased from Sigma.

Plasmids.

Plasmids pRep, pR68/78, pEYFPTetR, pECFPTetR, pBstetO, and pAAVlacO were described previously (13, 16, 20). Plasmid pSV2-EYFP/lacI, expressing a fusion gene for EYFP linked to the lac repressor (LacI) (46), was kindly provided by D. L. Spector (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY). Plasmid pALZ14ECFP-NHPX, encoding the nucleolar NHPX protein fused to ECFP under the control of the human cytomegalovirus IE1 enhancer/promoter (CMV promoter) (25), was kindly provided by A. I. Lamond (University of Dundee, Dundee, Scotland, United Kingdom). The standard HSV-1 amplicon plasmid pHSVPrPUC was kindly provided by H. J. Federoff (University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, NY). Plasmid p5CR, encoding mCherry fused to the N terminus of AAV Rep68/78 from the p5 promoter as well as unmodified Rep52/40 from the p19 promoter, was kindly provided by A. Salvetti (INSERM U758—ENSL, Lyon, France). Plasmid pCMV-8GFP, expressing GFP fused to the C terminus of HSV-1 ICP8 from the CMV promoter (43), was kindly provided by D. M. Knipe (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). Plasmid pcDNA-mRFP1-N, containing the gene for monomeric red fluorescent protein (mRFP) under the control of the CMV promoter, was kindly provided by U. F. Greber (Institute of Zoology, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland).

Construction of the other plasmids used in this study was done as follows. (i) For pHSV-tetO (an HSV-1 amplicon plasmid containing tetracycline operator [teto] sequences), a 1.65-kb HindIII-KpnI fragment of pBstetO (containing the teto sequences) (16) was inserted between the HindIII and KpnI sites of pHSVPrPUC, resulting in plasmid pHSV-tetO. pHSV-tetO contains a total of 35 TetR-binding sites. (ii) For plasmid pCMVUL29-mRFP (expressing mRFP fused to the C terminus of HSV-1 ICP8 from the CMV promoter), a 4.5-kb SpeI-SalI fragment of plasmid pCMV-8GFP (containing the UL29 open reading frame [ORF] and the C-terminal 688 bp of the CMV promoter) was inserted between the SpeI and SalI sites of the pBluescript SK(+) cloning vector (Stratagene), resulting in plasmid pCMVUL29. A 4.53-kb SpeI-KpnI fragment of pCMVUL29 (containing the UL29 ORF and the C-terminal 688 nt of the CMV promoter) was then inserted between the SpeI and KpnI sites of pcDNA-mRFP1-N (containing the N-terminal 152 nt of the CMV promoter and the mRFP ORF), resulting in pCMVUL29-mRFP. (iii) For plasmid pCMVmRFPLacI (expressing an mRFP-LacI fusion including a nuclear localization signal [NLS] from the CMV promoter), the ORF for mRFP without the stop codon was PCR amplified with primers containing a HindIII site at the 5′ end and an EcoRI site at the 3′ end, using plasmid pcDNA-mRFP1-N as the template. The resulting PCR product was inserted between the HindIII and EcoRI sites of pBluescript SK(+), resulting in plasmid pBsmRFP. Likewise, the ORF encoding LacI including an NLS was PCR amplified with primers containing an EcoRI site at the 5′ end and a NotI site at the 3′ end, using plasmid pSV2-EYFP/lacI as the template. The resulting PCR product was then ligated between the EcoRI and NotI sites on plasmid pBsmRFP, resulting in plasmid pBsmRFPLacI. Finally, a 1.8-kb HindIII-NotI fragment of pBsmRFPLacI (containing the mRFP-LacI fusion gene including an NLS) was inserted between the HindIII and NotI sites of pcDNA-mRFP1-N, resulting in pCMVmRFPLacI. (iv) For plasmid pCMVrep68/78_AL (encoding AAV2 Rep68/78 under the control of the CMV promoter), the ORF encoding AAV2 Rep68/78 was PCR amplified with primers introducing a BglII site at the 5′ end and a NotI site at the 3′ end, using plasmid pR68/78 as the template. The resulting PCR product was ligated between the BglII and NotI sites of pEGFP-N3 (Clontech), resulting in plasmid pCMVrep68/78_AL. The sequence of the rep68/78 ORF was confirmed by sequencing. (v) pCMVrep-ECFP-N3 (expressing the first 522 codons of rep68/78 fused to ECFP from the CMV promoter) was constructed in two steps. First, pECFP (Clontech) was cut with PinAI and XmaI and religated, resulting in pECFP-N3, with a shifted ORF for ECFP. Subsequently, a 0.74-kb BamHI-NotI fragment of pECFP-N3 (containing the gene for ECFP) was ligated with the 4.0-kb BamHI-NotI fragment of pEGFP-N3 (containing the vector backbone and the CMV promoter), resulting in pCMVECFP-N3. Second, a 1.62-kb BglII-KpnI fragment of pCMVrep-EGFP (containing the first 522 codons of rep68/78) (C. Fraefel, unpublished material) was inserted between the BglII and KpnI sites of pCMVECFP-N3, resulting in pCMVrep-ECFP-N3.

Transfection. (i) Live visualization assays.

The detailed procedure for live visualization assays was described previously (13). Briefly, the day before transfection, Vero or HeLa cells were seeded on either Lab-Tek four-well chambered cover glasses (Nalge Nunc International), for live cell microscopy, or round 12-mm cover glasses in 24-well plates, for subsequent immunofluorescence staining, at 105 cells/well. Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine Plus reagent as described by the manufacturer (Invitrogen). The amounts of individual plasmids used for transfection were as follows: pHSV-tetO, pAAVlacO, pBstetO, and pHSVPrPUC, 25 ng; and pEYFPTetR, pECFPTetR, pCMVmRFPLacI, pSV2-EYFP/lacI, pCMVUL29-mRFP, pALZ14ECFP-NHPX, pRep, and p5CR, 10 ng. Helper functions for HSV-1 amplicon and rAAV replication were provided by infection with wt HSV-1, vECFP-ICP4, or vEYFP-ICP4, as indicated in the text. For visualization of the nuclei in live cells, Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen) was added to the culture medium 30 min before observation, at a concentration of 1 μg/ml.

(ii) Transfection-infection experiments presented in Fig. 7 and 8.

FIG. 7.

Influence of AAV Rep68/78 proteins on HSV-1 RC formation. (A) Vero cells were transfected with plasmid pCMVrep68/78_AL, encoding Rep68/78 under the control of the CMV promoter, or plasmid pEGFP-N3, containing the same vector backbone and encoding EGFP instead of Rep68/78. On the following day, the cells were infected with HSV-1 at an MOI of 10 PFU. Cells were fixed at 0, 4, 8, and 12 h p.i. and stained with anti-ICP8 MAb 7381 and an AF594-conjugated secondary antibody (a to k; red). The cells in panels f to k were also stained with a rabbit serum specific for Rep and a FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (f to k; green). pEGFP-N3-tranfected cells were identified by EGFP fluorescence (a to e; green). Cells were observed by epifluorescence microscopy, and stages of HSV-1 replication were assessed according to the ICP8 staining pattern, as previously described (5, 27). The numbers indicate the proportions of cells in the respective stages at 12 h p.i. and are means ± standard deviations for triplicate experiments. (B) Time course of HSV-1 RC formation in transfected cells expressing EGFP or Rep68/78. The bars show the proportions of cells in the respective stages and represent the mean values for triplicate experiments.

FIG. 8.

Rep-induced numerous ICP8 foci are sites of active DNA synthesis. Vero cells were transfected with plasmid pCMVrep-ECFP-N3, encoding a Rep-ECFP fusion protein (a to d), or left untransfected (e to h). On the following day, the cells were infected with HSV-1 at an MOI of 10 PFU in the absence (a to d) or presence (e to h) of 400 μg/ml PAA. The cells were pulse labeled with 1 mM BrdU for 30 min before fixation at 12 h p.i. The cells were then stained with the rabbit anti-HSV-1 ICP8 serum 4-83 and a FITC-conjugated secondary antibody as well as with an anti-BrdU MAb and an AF594-conjugated secondary antibody. Cells were observed by CLSM, with settings specific for ECFP (Rep-ECFP fusion), FITC (ICP8), and AF594 (BrdU). The images represent projections through three-dimensional reconstructions of the nuclei.

Vero cells were transfected as described for the live visualization assays, except that 20 ng of pCMVrep68/78_AL, pEGFP-N3, or pCMVrep-ECFP-N3 was used. On the following day, the cells were infected with HSV-1 at an MOI of 10 PFU and fixed at the indicated time points.

Immunofluorescence.

Cells were washed once with cold phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4 (PBS), and fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS for 15 min at room temperature (RT), and the fixation was stopped with 0.1 M glycine in PBS for 5 min at RT. After being washed with cold PBS, cells were permeabilized with acetone for 2 min at −20°C and washed again three times with cold PBS. For detection of BrdU-labeled DNA, the cells were treated with 4 M HCl for 10 min at RT and washed three times with PBS. The cells were then blocked with PBS-B (PBS supplemented with 3% bovine serum albumin) for 15 min at RT and washed once with PBS. Cells were incubated with antibodies diluted in PBS-B for 1 h at RT and washed three times with PBS between incubations with primary and secondary antibodies. Primary antibodies were used at the following dilutions: anti-HSV-1 ICP8 MAb 7381, 1:1,000; anti-HSV-1 ICP4 MAb, 1:200; rabbit anti-AAV Rep serum, 1:400; rabbit anti-HSV-1 ICP8 serum 4-83, 1:250; and anti-BrdU MAb clone BMC 9318, 1:20 (5 μg/ml). Secondary antibodies were used at the following dilutions: goat anti-rabbit IgG(H+L)-FITC, 1:100; and goat anti-mouse IgG(H+L)-AF594, 1:100 to 1:500. For visualization of the nuclei, the cells were incubated with 1 μg/ml DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Roche) in PBS for 15 min at RT. Finally, the cells were washed three times with PBS and once with water and then mounted in Glycergel (DakoCytomation) containing 25 mg/ml DABCO (1, 4-diazabicyclo [2.2.2] octane; Fluka) to retard bleaching.

Microscopy.

Live or fixed cells were observed by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) on a Leica TCS SP2 AOBS microscope or by epifluorescence microscopy on a Zeiss Axiovert S100 microscope equipped with a Hamamatsu C5810 3CCD chilled color camera. Images from CLSM were deconvolved with a blind deconvolution algorithm, using Huygens Essential 2.6.0p1 software (SVI), and processed with Imaris 5.0.1 (Bitplane AG) and Adobe Photoshop Elements 2.0 software (Adobe).

Slot blotting.

The day before infection, HeLa cells were plated in 24-well plates at 2 × 105 cells/well. The cells were mock infected, infected with HSV-1 at an MOI of 1 PFU, or coinfected with HSV-1 (MOI, 1 PFU) and wt AAV2 (MOI, 10, 100, or 1,000 IU) or rAAV2-GFP (MOI, 10, 100, or 1,000 TU) in DMEM. After 2 h of absorption, the cells were washed with PBS and covered with DMEM containing 2% FBS. At 48 h postinfection (p.i.), the cells were harvested and lysed in 1 ml lysis buffer (0.4 M NaOH, 10 mM EDTA) and then boiled for 10 min. The lysate was further diluted 1:10 in lysis buffer, and 300 μl thereof (6 × 103 cell equivalents) was spotted onto a positively charged nylon membrane (Roche), using a Bio-Dot SF microfiltration apparatus (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's manual. HSV-1 DNA was detected with a digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled probe for the entire HSV-1 UL35 ORF, which was PCR amplified with primers UL35-5′Ngo (5′TTGAGGCCGGCGCAATTTCACCGCCCCAGCACCG3′) and UL35-3′Not/Spe (5′AAAGAGCGGCCGCACTAGTGGTGTGGTCTTTTATTGATTAAAACACCCCAG3′) from a cloned HSV-1 strain F genome (YE102 bacterial artificial chromosome) (41), using a PCR DIG probe synthesis kit (Roche) according to the manufacturer's manual. Hybridization with the DIG-labeled probe and immunological detection were performed as previously described (13, 20), except that DIG Easy Hyb (Roche) was used as hybridization buffer. Scanned blots were quantified using Quantity One 4.6.1 software (Bio-Rad).

Western blotting.

The day before infection, HeLa cells were plated in 12-well plates at 4 × 105 cells/well. Infections were carried out as described for the slot blot analysis. At 48 h p.i., the cells were washed with PBS, lysed in 200 μl protein loading buffer (containing 62 mM Tris base, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol, and 0.005% bromphenol blue), and boiled for 10 min. Twenty-microliter aliquots of the lysates (4 × 104 cell equivalents) were separated in SDS-8% (for detection of ICP4 and ICP8) or 10% (for detection of VP16, gC, Rep, and GFP) polyacrylamide gels and transferred to Protran nitrocellulose membranes (Whatman). The membranes were blocked with PBS-T (PBS containing 0.3% Tween 20) supplemented with 5% nonfat dry milk for 1 h at RT. Incubation with antibodies was carried out in PBS-T supplemented with 2.5% dry milk. Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C, while secondary antibodies were incubated for 1 h at RT. The primary antibodies were used at the following dilutions: anti-HSV-1 ICP4 MAb, 1:10,000; anti-HSV-1 ICP8 MAb clone 10A3, 1:10,000; anti-HSV-1 VP16 MAb LP1, 1:4,000; rabbit anti-HSV-1 gC serum R47, 1:50,000; anti-AAV Rep MAb clone 303.9, 1:200; anti-GFP MAb JL-8, 1:2,000; and rabbit anti-actin polyclonal antibody H300, 1:1,000. The secondary antibodies were used as follows: rabbit anti-mouse IgG (whole molecule)-peroxidase, 1:10,000 (for detection of ICP4, ICP8, Rep, and GFP) or 1:100,000 (for detection of VP16); and goat anti-rabbit IgG(H+L)-horseradish peroxidase, 1:10,000. Membranes were washed three times with PBS-T after each incubation step. Membranes were stripped with Restore Western blot stripping buffer (Pierce) for 20 min at 37°C before being reprobed with a different primary antibody. Bound secondary antibodies were detected with ECL Western blotting detection reagent (Amersham Biosciences), and the membranes were exposed to Lumi-Film chemiluminescence detection films (Roche). Scanned blots were quantified using Quantity One 4.6.1 software (Bio-Rad).

RESULTS

Live covisualization of AAV and HSV-1 DNA replication.

In order to directly assess the reciprocal interaction between AAV and HSV-1 on the single-cell level, we set out to visualize the replication of an rAAV genome and an HSV-1 amplicon plasmid in live cells. For visualization of rAAV DNA replication, we used a previously described visualization system employing the interaction of the lac repressor (LacI) fused to autofluorescent proteins with lac operator sequences (LacO) present in an rAAV genome (rAAVlacO) (13). An EYFP-LacI fusion was expressed from plasmid pSV2-EYFP/lacI (46), while an mRFP-LacI fusion was expressed from plasmid pCMVmRFPLacI. For the visualization of HSV-1 amplicon replication, we employed the interaction of tetracycline operator (TetO) sequences present within an HSV-1 amplicon plasmid (pHSV-tetO) with the tetracycline repressor (TetR) DNA-binding domain fused to autofluorescent proteins. The TetR DNA-binding domain fused to EYFP or ECFP was expressed from plasmid pEYFPTetR or pECFPTetR, as described previously (16). The HSV-1 helper factors for rAAVlacO and pHSV-tetO replication were provided by infection with HSV-1, while the AAV Rep proteins were provided by cotransfection of plasmids expressing AAV rep from its native promoters (plasmid pRep or p5CR). A schematic representation of the covisualization system is shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of live covisualization of competing viral replication origins. Replication of an HSV-1 amplicon vector is visualized with plasmid pHSV-tetO, which contains the HSV-1 oriS, the HSV-1 DNA packaging/cleavage signal (pac), and five reiterations of the seven-copy teto sequence, comprising a total of 35 TetR binding sites. In the presence of HSV-1 replication factors, the accumulation of concatemeric HSV-1 amplicon replication products (HSV Cc.) is visualized by binding of an EYFP-TetR or ECFP-TetR fusion protein. Visualization of rAAV replication, which employs interactions of an mRFP-LacI or EYFP-LacI fusion protein with laco repeats present in an rAAV genome (rAAVlacO), has been described previously (13). Double-stranded monomeric (AAV ITRm) and dimeric (AAV ITRd) rAAV replication intermediates are indicated.

In a first step, we tested the functionality of our visualization system for HSV-1 amplicon replication. For this step, Vero cells were cotransfected with plasmids pEYFPTetR and pHSV-tetO or with control plasmids lacking either the HSV-1 oriS (pBstetO) or the TetO sequences (pHSVPrPUC) and then infected with the recombinant HSV-1 vECFP-ICP4 expressing ECFP fused to the N terminus of ICP4 (11) or mock infected. The formation of HSV-1 amplicon RCs recruiting EYFP-TetR was observed only in cells cotransfected with pHSV-tetO and pEYFPTetR and infected with HSV-1 (Fig. 2A). Notably, the ECFP-ICP4 fusion protein was recruited to both the HSV-1 helper virus RCs and the HSV-1 amplicon RCs, although with a lower affinity for the latter. Similarly, an ICP8-mRFP fusion protein was localized to both the helper virus and the HSV-1 amplicon RCs in the characteristic punctate staining pattern (data not shown). Consistent with previous reports, HSV-1 amplicon and HSV-1 helper virus RCs were clearly distinguishable and did not merge (10, 38). However, in the absence of pHSV-tetO RC formation, nonspecific small nuclear foci of EYFP-TetR were observed. Cotransfection of a plasmid encoding the nucleolar NHPX protein fused to ECFP (25) revealed that these small foci were invariably localized to the nucleoli (Fig. 2B). Notably, the small nonspecific foci disappeared upon the addition of tetracycline to the culture medium, indicating that the binding of EYFP-TetR to the nucleolus is mediated by the TetR DNA-binding domain (data not shown). Nevertheless, the small nonspecific EYFP-TetR foci could readily be distinguished from large, mature pHSV-tetO RCs. Interestingly, such nonspecific EYFP/ECFP-TetR foci were not observed in a previous study by Sourvinos and Everett, in which a similar live visualization system for HSV-1 DNA was employed to study the association of parental HSV-1 genomes with ND10 and the dynamics of HSV-1 RC formation (38). In this previous study, the fusion proteins were expressed by transduction of cells with an HSV-1 amplicon vector instead of transfection (38). Possibly, in our study, the high expression levels of EYFP/ECFP-TetR 1 day after transfection allowed for the formation of nonspecific foci, while in the study of Sourvinos and Everett, the cells were observed in the first hours after transduction, a period probably too short for formation of such nonspecific foci (38). Taken together, these data demonstrate the functionality of our live visualization system for HSV-1 amplicon replication and, at the same time, show that the observed RCs behave similar to the HSV-1 helper virus RCs with regard to size and ICP8 staining pattern, while recruiting smaller amounts of ICP4 than the HSV-1 helper virus RCs.

FIG. 2.

Live covisualization of HSV-1 amplicon replication and HSV-1 ICP4. (A) Nuclear distribution of EYFP-TetR and ECFP-ICP4. Vero cells were cotransfected with pHSV-tetO (a to f), pBstetO (g to i), or pHSVPrPUC (k to m) and pEYFPTetR (a to m). On the following day, the cells were infected with recombinant HSV-1 expressing ECFP fused to ICP4 (vECFP-ICP4) at an MOI of 5 PFU (a to c and g to m) or were mock infected (d to f). Live cells were observed by CLSM at 12 to 16 h p.i., with settings specific for EYFP (EYFP-TetR fusion protein) and ECFP (ECFP-ICP4 fusion protein). The images represent projections through three-dimensional reconstructions of the nuclei. (B) Nuclear distribution of EYFP-TetR and the nucleolus marker ECFP-NHPX. Vero cells were cotransfected with pEYFPTetR and pALZ14ECFP-NHPX. On the following day, live cells were observed as described for panel A, using settings specific for EYFP (EYFP-TetR fusion protein) and ECFP (ECFP-NHPX fusion protein).

In a second step, we combined the visualization systems for HSV-1 amplicon and rAAV DNA replication. For this purpose, pHSV-tetO RCs were detected with EYFP-TetR, and rAAVlacO RCs were detected with mRFP-LacI. While the majority of cells that displayed mature rAAV RCs did not contain any HSV-1 amplicon RCs, a subset of cells displayed the simultaneous formation of mature rAAV and mature HSV-1 amplicon RCs. In these cells, the rAAV RCs formed separately from the HSV-1 amplicon RCs. However, it appeared that they were often localized in close proximity, probably reflecting the shared requirement for HSV-1 helper factors (Fig. 3A). In the next experiment, we aimed to analyze the distribution of AAV Rep proteins in relation to rAAV and HSV-1 amplicon RCs. For this experiment, pHSV-tetO RCs were detected with ECFP-TetR and rAAVlacO RCs were detected with EYFP-LacI, while the large Rep proteins were expressed with mCherry fused to their N termini. While Rep proteins were strongly recruited into the rAAV compartments, no such accumulation was observed in HSV-1 amplicon compartments (Fig. 3B and C). These findings are consistent with the presence of strong Rep-binding sites in the rAAV ITRs, but not in the HSV-1 amplicon plasmid, and underscore the formation of distinct rAAV and HSV-1 amplicon RCs.

FIG. 3.

Live covisualization of HSV-1 amplicon and rAAV DNA replication. (A) Independent formation of HSV-1 amplicon and rAAV RCs. HeLa cells were cotransfected with pHSV-tetO, pAAVlacO, pEYFPTetR, pCMVmRFPLacI, and pRep. On the following day, the cells were infected with HSV-1 at an MOI of 5 PFU. Live cells treated with 1 μg/ml Hoechst 33342 were observed by CLSM at 12 to 16 h p.i., with settings specific for EYFP (pHSV-tetO RCs), mRFP (rAAVlacO RCs), and Hoechst. The images represent single z stacks of the nuclei. (B) Formation of HSV-1 amplicon and rAAV RCs and nuclear distribution of AAV Rep. HeLa cells were cotransfected with pHSV-tetO, pAAVlacO, pECFP-TetR, pSV2-EYFP/lacI, and p5CR. On the following day, the cells were infected with HSV-1 at an MOI of 1 PFU. Live cells were observed by CLSM at 48 to 72 h p.i., with settings specific for ECFP (pHSV-tetO RCs), EYFP (rAAVlacO RCs), and mCherry (mCherry-Rep68/78 fusion proteins). The images represent projections through three-dimensional reconstructions of the nuclei. (C) Three-dimensional views of the nucleus shown in panel B. pHSV-tetO RCs are stained blue, rAAVlacO RCs are stained green, and mCherry-Rep68/78 proteins are stained red. Deconvolved three-dimensional reconstructions of the nucleus were processed in Imaris software, using the surpass view mode.

The relatively infrequent coexistence of rAAV and HSV-1 amplicon RCs suggested that HSV-1 amplicon replication is inhibited in the presence of AAV DNA replication. In order to test this possibility, we quantified the proportion of transfected HeLa cells positive for mature HSV-1 amplicon RCs in the presence or absence of rAAV replication (i.e., rAAV DNA and AAV Rep proteins). Again, HSV-1 helper factors were provided by infection with HSV-1. Indeed, while 30% ± 2.4% of the cells transfected with pHSV-tetO and pEYFPTetR alone were positive for HSV-1 amplicon RCs, this proportion was reduced to 5.7% ± 1.5% in cells cotransfected with pHSV-tetO, pEYFPTetR, pAAVlacO, and the rep-expressing plasmid p5CR.

HSV-1 ICP8, but not ICP4, is recruited into rAAV RCs.

HSV-1 ICP8 is an essential replication factor for both HSV-1 and AAV DNA replication (50, 53) and nonspecifically binds ssDNA, as demonstrated by the fact that it is found not only in HSV-1 RCs but also in AAV RCs and even at sites of cellular DNA synthesis (9, 19, 27, 40, 47). The HSV-1 transcriptional regulatory protein ICP4, on the other hand, displays sequence-specific DNA-binding activity, with binding sites located throughout the HSV-1 genome (2, 12, 30, 31). Consistent with this, ICP4 binds to both parental HSV-1 genomes and progeny virus DNA (11, 23, 34). In order to analyze the distribution of ICP8 with respect to rAAV replication, rAAVlacO RCs were detected with EYFP-LacI, while ICP8 was detected either by antibody staining (Fig. 4A) or by expression of an ICP8-mRFP fusion protein (Fig. 4B). While in some cells ICP8 was localized almost exclusively to rAAV RCs (Fig. 4A, panels a to d), in other cells we observed binding of ICP8 to the rAAV DNA as well as to compartments outside the rAAV RCs, probably representing RCs of the HSV-1 helper virus or of the rep-expressing plasmid pRep (Fig. 4A, panels e to h, and B, panels a to d). Plasmid pRep contains the p5 origin of DNA replication (p5 ori) and has previously been shown to replicate efficiently in the presence of HSV-1 helper functions (16). Note that the staining pattern of ICP8 within the rAAV compartments was more homogenous than the punctate pattern observed within the HSV-1 or pRep RCs, again underlining the differential nature of AAV ITR, AAV p5, and HSV-1 RCs. We next analyzed the distribution of ICP4, either by antibody staining (Fig. 4C) or with an EYFP-ICP4 fusion protein expressed by the recombinant HSV-1 vEYFP-ICP4 (11) (Fig. 4D). In cells displaying mature rAAV RCs, ICP4 showed a diffuse distribution within the nucleus (Fig. 4C, panels a to d) or else was recruited into HSV-1 helper virus RCs distinct from the rAAV RCs (Fig. 4C, panels e to h, and D, panels a to d). Taken together, these results confirm the formation of separate AAV and HSV-1 RCs observed with the live covisualization assays shown in Fig. 3.

FIG. 4.

rAAV DNA replication and nuclear distribution of HSV-1 ICP8 and ICP4. (A) Covisualization of rAAV DNA and ICP8 protein. Vero cells were cotransfected with pAAVlacO, pSV2-EYFP/lacI, and pRep. On the following day, the cells were infected with HSV-1 at an MOI of 5 PFU. At 14 h p.i., the cells were fixed and stained with anti-ICP8 MAb 7381 and an AF594-conjugated secondary antibody, as well as DAPI. The cells were then observed by CLSM, with settings specific for EYFP (rAAVlacO RCs), AF594 (ICP8), and DAPI. Images represent single z stacks of the nuclei. (B) Live covisualization of rAAV DNA and ICP8. Vero cells were cotransfected with pAAVlacO, pSV2-EYFP/lacI, pCMVUL29-mRFP, and pRep. On the following day, the cells were infected with HSV-1 at an MOI of 5 PFU. Live cells treated with 1 μg/ml Hoechst 33342 were observed by CLSM at 12 to 16 h p.i., with settings specific for EYFP (rAAVlacO RCs), mRFP (ICP8-mRFP fusion protein), and Hoechst. Images represent a single z stack of a nucleus. (C) Covisualization of rAAV DNA and ICP4. Vero cells were transfected, infected, stained, and observed as described for panel A, except that a MAb specific for ICP4 was used. (D) Live covisualization of rAAV DNA and ICP4. Vero cells were cotransfected with pAAVlacO, pCMVmRFPLacI, and pRep. On the following day, the cells were infected with recombinant HSV-1 expressing EYFP fused to ICP4 (vEYFP-ICP4) at an MOI of 5 PFU. Live cells were observed as described for panel B, with settings specific for mRFP (rAAVlacO RCs), EYFP (EYFP-ICP4 fusion protein), and Hoechst.

wt AAV2, but not a rep-negative rAAV2, inhibits HSV-1 DNA replication.

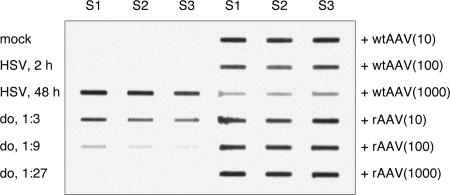

In order to find out if the observed inhibition of HSV-1 amplicon replication in the presence of rAAV DNA and AAV rep also holds true for the respective wt viruses, we set out to analyze the influence of AAV2 coinfection on HSV-1 DNA replication. For this purpose, HeLa cells were infected with HSV-1 and coinfected with increasing amounts of wt AAV2 or a rep-negative, replication-deficient rAAV2-GFP vector. Notably, at 48 h p.i., HSV-1-induced cytopathic effects were visible and comparable in all cultures, either infected with HSV-1 alone or coinfected with HSV-1 and either wt AAV2 or rAAV-GFP (data not shown). The cells were then lysed and the DNA analyzed by slot blot hybridization with a probe specific for HSV-1 UL35. Clearly, wt AAV2, but not the rep-negative rAAV2-GFP, inhibited HSV-1 DNA replication in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5). The respective bands were quantified by densitometry, with threefold serial dilutions of HSV-1 replication products in the absence of AAV2 coinfection serving as the standard curve. The amount of HSV-1 replication products in the absence of AAV2 coinfection was set as 100%. The results from the quantification are summarized in Table 1. At the highest dose of wt AAV2 used (1,000 IU), the amount of replicated HSV-1 DNA was reduced to approximately 23%, while even the highest dose of rAAV2-GFP (1,000 TU) did not inhibit HSV-1 DNA replication. In contrast, the presence of replication-defective rAAV genomes appeared to have a slightly stimulatory, rather than inhibitory, effect on HSV-1 DNA replication, as judged by band-intensity readings over 100%. In summary, these results demonstrate a dose-dependent inhibition of HSV-1 DNA replication by wt AAV2 but not by the rep-negative, replication-defective rAAV2-GFP. The data further indicate that although coinfection with wt AAV2 inhibits HSV-1 DNA replication, it does not inhibit or delay the HSV-1-induced cytopathic effects.

FIG. 5.

Influence of AAV2 coinfection on HSV-1 DNA replication. Triplicate wells of HeLa cells were mock infected, infected with HSV-1 (MOI, 1 PFU), coinfected with HSV-1 (MOI, 1 PFU) and wt AAV2 (MOI, 10, 100, or 1,000 IU), or coinfected with HSV-1 (MOI, 1 PFU) and rAAV2-GFP vector (MOI, 10, 100, or 1,000 TU). At 48 h p.i., the cells were harvested, and HSV-1 DNA was detected by slot blotting and hybridization with a probe specific for HSV-1 UL35. Threefold serial dilutions (do) of HSV-1 replication products in the absence of AAV infection were used for quantification of HSV-1 replication products in the presence of AAV coinfection. S1 to S3, sample numbers for triplicate samples; HSV, HSV-1 infected; +wtAAV, coinfected with HSV-1 and wt AAV2; +rAAV, coinfected with HSV-1 and rAAV2-GFP. The numbers in parentheses indicate the MOIs of AAV2 and rAAV2-GFP in IU and TU, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Quantification of HSV-1 DNA replication products presented in Fig. 5

| Infection | Relative amt (%) of HSV-1 DNA |

|---|---|

| Mock | ≤3.7 |

| HSV-1 (input virus) | ≤3.7 |

| HSV-1 | 100 |

| HSV-1 + AAV2 (MOI, 10) | ≥100 |

| HSV-1 + AAV2 (MOI, 100) | 60 |

| HSV-1 + AAV2 (MOI, 1,000) | 23 |

| HSV-1 + rAAV2-GFP (MOI, 10) | ≥100 |

| HSV-1 + rAAV2-GFP (MOI, 100) | ≥100 |

| HSV-1 + rAAV2-GFP (MOI, 1,000) | ≥100 |

wt AAV2 coinfection inhibits HSV-1 late gene expression.

We then proceeded to analyze the influence of AAV2 coinfection on HSV-1 protein expression. The facts that (i) AAV does not inhibit the cytopathic effects caused by HSV-1 infection (data not shown), which can be mediated by IE gene products (8, 21), and (ii) the HSV-1 helper factors that are essential for AAV replication (in particular UL5, UL8, UL52, and UL29) are all expressed with early kinetics (49, 50) led us to the hypothesis that AAV-mediated inhibition may occur at a late stage of HSV-1 replication without affecting IE and early gene expression. In order to examine this possibility, we performed coinfection experiments with HSV-1 and either wt AAV2 or rAAV2-GFP, as described for Fig. 5. At 48 h p.i., the cells were lysed and used for SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blotting. We used antibodies for detection of four HSV-1 proteins, in particular (i) ICP4, expressed with IE kinetics; (ii) ICP8, expressed with early kinetics; (iii), the IE transactivator protein VP16, expressed with leaky late (γ1) kinetics; and (iv) the envelope glycoprotein C (gC), expressed with true late (γ2) kinetics (Fig. 6). While the levels of ICP4 and ICP8 were moderately reduced by wt AAV2 coinfection, the accumulation of VP16 and gC was strongly inhibited (Fig. 6A). In particular, at the highest dose of wt AAV2, the relative signal intensities were reduced to 66% for ICP4, 47% for ICP8, 0% for VP16, and 13% for gC. In contrast, coinfection with the rep-negative rAAV2-GFP appeared to have a slightly stimulatory effect on ICP4, ICP8, and VP16 levels, while modestly lowering the gC level (Fig. 6A). The blots were also probed with antibodies against AAV Rep and GFP in order to control for efficient infection of cells by wt AAV2 and rAAV2-GFP. As shown in Fig. 6B, infection with increasing doses of wt AAV2 or rAAV2-GFP led to increasing accumulation of AAV Rep proteins and GFP, respectively. Together with the data shown in Fig. 5, these data demonstrate that coinfection with wt AAV2 only modestly affects HSV-1 IE and early gene expression but markedly inhibits HSV-1 DNA replication and late gene expression and that AAV2 gene expression and/or AAV2 DNA replication is responsible for the effect. However, these results do not specify whether inhibition of HSV-1 replication is mediated by a function of Rep proteins or by competition for essential HSV-1 replication factors between replicating HSV-1 and AAV2 genomes.

FIG. 6.

Influence of AAV2 coinfection on HSV-1 protein levels. HeLa cells were mock infected, infected with HSV-1 (MOI, 1 PFU), coinfected with HSV-1 (MOI, 1 PFU) and increasing amounts of wt AAV2 (MOI, 10, 100, and 1,000 IU), or coinfected with HSV-1 (MOI, 1 PFU) and increasing amounts of rAAV2-GFP vector (MOI, 10, 100, and 1,000 TU). At 48 h p.i., the cells were analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blotting with antibodies specific for (A) HSV-1 ICP4, HSV-1 ICP8, HSV-1 VP16, and HSV-1 gC or (B) AAV Rep and GFP. Detection of actin served as a loading control. A sample of HSV-1-infected cells were lysed after 2 h of absorption, representing the input HSV-1 virus. In panel A, the relative signal intensities (normalized to that for actin) are indicated as percentages. The signal intensity of mock-infected cells was set to 0%, while that of cells infected with HSV-1 alone was set to 100%. M, mock infected; 2 h, HSV-1 infected and harvested after 2 h of absorption; wtAAV, wt AAV2 infected; rAAV, rAAV2-GFP infected.

Preexisting AAV Rep68/78 proteins inhibit the formation of mature HSV-1 RCs.

In order to test whether the presence of Rep68/78 proteins is sufficient for the observed inhibition of HSV-1 replication, we transfected Vero cells with a plasmid encoding Rep68/78 under the control of the CMV promoter (pCMVrep68/78_AL) or a control plasmid encoding EGFP in place of Rep68/78 (pEGFP-N3). The cells were then incubated for 24 h to allow for the synthesis of Rep proteins before infection with HSV-1 at an MOI of 10 PFU. Samples of infected cells were fixed at 0, 4, 8, and 12 h p.i. and stained for HSV-1 ICP8 and AAV Rep proteins. The progression of HSV-1 infection in rep-expressing cells was analyzed and compared to that in control cells expressing EGFP. Stages of HSV-1 replication were assessed according to the ICP8 staining pattern, as previously described (5, 27). As shown in Fig. 7, the progression from stages I to IV was markedly inhibited in cells expressing rep. At 12 h p.i., the proportion of cells displaying mature (stage IV) HSV-1 RCs was reduced to 3% in rep-expressing cells compared to 78% in control cells, while the proportion of cells in stage I was increased to 31% compared to 6% in the control cells. Strikingly, 52% of rep-expressing cells accumulated numerous small nuclear ICP8 foci (Fig. 7A, panel k). This pattern is reminiscent of the recruitment of ICP8 to sites of cellular DNA synthesis (previously termed “numerous prereplicative sites”), which occurs when cells are infected in the presence of viral polymerase inhibitors, such as phosphonoacetic acid (PAA) or acyclovir, or else when cells are infected with polymerase-deficient viruses (27, 47). Consistent with such numerous ICP8 foci being sites of cellular DNA synthesis, they incorporate BrdU and colocalize with proteins involved in host cell DNA synthesis (27, 47). We therefore compared Rep-induced and PAA-induced numerous ICP8 foci by assessing BrdU incorporation. Vero cells were transfected with plasmid pCMVrep-ECFP-N3, which encodes a Rep-ECFP fusion protein under the control of the CMV promoter. On the following day, the cells were infected with HSV-1 at an MOI of 10 PFU. As a control, untransfected cells were infected in the presence of PAA. Pulse labeling with BrdU and staining with BrdU- and ICP8-specifc antibodies demonstrated that Rep-induced numerous ICP8 foci are associated with sites of active DNA synthesis (Fig. 8, panels a to d), similar to PAA-induced numerous ICP8 foci (Fig. 8, panels e to h). This finding suggests that Rep-induced numerous ICP8 foci, in analogy to their PAA-induced counterparts, correspond to sites of cellular DNA synthesis. Taken together, these data demonstrate that preexisting Rep68/78 proteins at the time of infection severely inhibit the formation of HSV-1 RCs and lead to the accumulation of ICP8 at sites of cellular DNA synthesis.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we set out to investigate the interaction between two competing viruses, namely, AAV and its helper virus HSV-1. In a first set of experiments, we directly assessed the reciprocal interaction between replicating AAV and HSV-1 DNAs, using live cell visualization assays for rAAV and HSV-1 amplicon replication (Fig. 1). The assays demonstrated the simultaneous formation of rAAV and HSV-1 amplicon RCs in a subset of the observed cells. In the majority of cells displaying mature rAAV RCs, however, mature HSV-1 amplicon RCs were not detected, indicating inhibition of HSV-1 amplicon replication in the presence of rAAV DNA and AAV Rep proteins. Notably, rAAV and HSV-1 amplicon DNAs were found to replicate in separate RCs, which were often found in close proximity to each other, possibly reflecting the shared requirement for HSV-1 replication factors (Fig. 3). AAV and HSV-1 RCs could be distinguished not only by visualization of the replicating DNAs but also by their staining patterns for several viral and cellular proteins. First, the sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins AAV Rep and HSV-1 ICP4 discriminated rAAV from HSV-1 RCs. In particular, Rep colocalized with rAAV DNA but not with HSV-1 amplicon DNA, while ICP4 accumulated in HSV-1 helper virus RCs but not in rAAV RCs (Fig. 3 and 4). Second, the ssDNA-binding protein HSV-1 ICP8, although localizing to both rAAV and HSV-1 RCs, displayed differential staining patterns. Specifically, ICP8 was found in a punctate staining pattern within HSV-1 RCs, consistent with binding to the single-stranded HSV-1 DNA at the replication forks but not to the double-stranded HSV-1 replication products. In contrast, ICP8 showed a more homogenous distribution within rAAV RCs, reflecting binding to both the single-stranded AAV DNA at the replication forks and the single-stranded rAAV replication products (Fig. 4). Third, we observed hyperphosphorylated replication protein A (RPA) in rAAV RCs, while hyperphosphorylated RPA did not localize to productive HSV-1 RCs, indicating the induction of differential DNA damage responses by AAV and HSV-1 (52; Strasser et al., unpublished data). Taken together, these observations demonstrate that AAV and HSV-1 RCs develop as spatially separate entities accumulating distinct sets of viral and cellular proteins. This finding is in contradiction with the assumption that AAV is replicated within HSV-1 RCs, which was put forward in an earlier report (19). The previous conclusion was based on staining patterns of Rep and ICP8 and likely on the assumed similarity to the situation where Ad acts as the helper virus. According to our results, however, the situation with HSV-1 as the helper virus clearly appears to be different from that described for Ad-aided AAV replication, in which AAV DNA colocalizes with Ad DNA in early RCs (51). Nevertheless, in analogy to our results, the maturation of Ad RCs is significantly inhibited by AAV coinfection or rep overexpression (51). The mechanisms accounting for these differences still remain to be determined. It is possible that the differential influence of components of the cellular DNA repair machinery, for example, the Mre11-Rad50-NBS1 complex, on HSV-1 and Ad replication may be involved in the processes guiding the formation of AAV, HSV-1, and Ad RCs (26, 39). However, our findings of the formation of separate AAV and HSV-1 RCs are consistent with the previously formulated hypothesis that viral RCs are clonal (i.e., derived from individual parental genomes) and do not merge even after they have expanded to fill large volumes of the nucleus (10, 16, 38).

In a second set of experiments, we investigated the molecular mechanisms of AAV-mediated inhibition of HSV-1 replication, as observed with the live covisualization assays. The analysis of cells coinfected with HSV-1 and either wt AAV2 or rAAV2-GFP at the levels of HSV-1 DNA (Fig. 5) and HSV-1 proteins (Fig. 6) suggests that AAV-mediated inhibition of HSV-1 replication occurs at the level of DNA replication, while only modestly affecting IE and early gene expression, and that the effect is dependent on AAV replication and/or rep expression. In order to dissect whether AAV DNA replication is required or, alternatively, the Rep proteins per se are sufficient for the inhibition of HSV-1, we analyzed HSV-1 RC formation in the presence of rep overexpression (Fig. 7). The assay revealed a pronounced inhibition of HSV-1 RC formation and the accumulation of ICP8 at sites of cellular DNA synthesis, a phenomenon previously observed in the presence of viral polymerase inhibitors (27, 47). Only recently was it shown that the presence of an inhibited viral polymerase induces the hyperphosphorylation of RPA and its accumulation at S-phase-specific sites (52). It is possible that Rep induces a similar response. However, the detailed analysis of viral and cellular proteins associated with Rep-induced numerous ICP8 foci was postponed to future studies. The findings that (i) cotransfection of rAAV DNA and AAV rep reduces the frequency of mature HSV-1 amplicon RCs approximately fivefold, (ii) coinfection of HSV-1-infected cells (MOI, 1 PFU) with wt AAV2 (MOI, 1,000 IU) reduces the amount of HSV-1 DNA replication products about fourfold (Fig. 5), and (iii) HSV-1 RCs can coexist with AAV RCs (Fig. 3 and 4) indicate that AAV-mediated inhibition of HSV-1 replication is far from being complete. We therefore hypothesize that in the situation of an AAV-HSV-1 coinfection, the initially low Rep levels allow a certain degree of HSV-1 replication, and that only the abundant Rep levels present in a late stage of AAV replication severely impede the progression of HSV-1 replication. Consistent with this hypothesis, expression of rep from its native promoters allows for the coexistence of mature AAV and HSV-1 RCs (Fig. 3 and 4), while the preexpression of Rep68/78 from the strong CMV promoter almost does not allow for the formation of mature HSV-1 RCs (Fig. 7). Overall, our results are consistent with a recent report on the interaction of AAV with Ad (44). It was demonstrated that AAV coinfection, and in particular the AAV Rep78 protein, mainly inhibited Ad E4 and late transcription and, to a lesser extent, E1A and E2A. Interestingly, transfected Rep78 did not reduce E2A and E4 transcript levels prior to DNA replication, nor did AAV coinfection affect E2A and E4 mRNA production in the presence of hydroxyurea. It was concluded that AAV replication and/or rep gene expression inhibits Ad DNA replication and that the reduced early gene expression is a consequence rather than the cause of inhibited DNA replication (44). Although not directly assessed in the present study, it remains plausible that the moderate decrease in HSV-1 ICP4 and ICP8 protein levels observed in the presence of wt AAV2 was due to inhibited DNA replication, resulting in reduced levels of templates for transcription.

The unique requirement for helper virus coinfection might ensure that AAV only replicates in cells that are no longer beneficial to the host, thus contributing to the wide distribution of this otherwise nonpathogenic virus. However, since it is likely that both AAV and its helper viruses share factors of the replication machinery, it is plausible that AAV has evolved mechanisms which limit excessive replication of the helper virus, e.g., HSV-1. The findings in this report suggest that AAV has evolved a strategy to inhibit HSV-1 replication without affecting the synthesis and function of helper virus factors that are supportive of AAV replication (i.e., the IE gene product ICP0 and the products of the early genes UL5, UL8, UL52, and UL29) (14, 50). However, the precise molecular mechanisms underlying this strategy remain to be determined.

Acknowledgments

We kindly thank H. Browne, G. H. Cohen, R. J. Eisenberg, R. D. Everett, H. I. Federoff, U. F. Greber, D. M. Knipe, A. I. Lamond, A. Minson, A. Salvetti, and D. L. Spector for providing reagents and I. Heid for technical assistance.

This work was supported by Swiss National Science Foundation grants 3100A0-100195 and 3100AO-112462 (C.F.) and U.S. National Institutes of Health grants R01GM071023 and ROIGM073901 (R.M.L.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 21 February 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bantel-Schaal, U., and H. zur Hausen. 1988. Adeno-associated viruses inhibit SV40 DNA amplification and replication of herpes simplex virus in SV40-transformed hamster cells. Virology 164:64-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beard, P., S. Faber, K. W. Wilcox, and L. I. Pizer. 1986. Herpes simplex virus immediate early infected-cell polypeptide 4 binds to DNA and promotes transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83:4016-4020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berthet, C., K. Raj, P. Saudan, and P. Beard. 2005. How adeno-associated virus Rep78 protein arrests cells completely in S phase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:13634-13639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buller, R. M., J. E. Janik, E. D. Sebring, and J. A. Rose. 1981. Herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 completely help adenovirus-associated virus replication. J. Virol. 40:241-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burkham, J., D. M. Coen, and S. K. Weller. 1998. ND10 protein PML is recruited to herpes simplex virus type 1 prereplicative sites and replication compartments in the presence of viral DNA polymerase. J. Virol. 72:10100-10107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark, K. R., F. Voulgaropoulou, and P. R. Johnson. 1996. A stable cell line carrying adenovirus-inducible rep and cap genes allows for infectivity titration of adeno-associated virus vectors. Gene Ther. 3:1124-1132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen, G. H., D. Long, and R. J. Eisenberg. 1980. Synthesis and processing of glycoproteins gD and gC of herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol. 36:429-439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cuchet, D., R. Ferrera, P. Lomonte, and A. L. Epstein. 2005. Characterization of antiproliferative and cytotoxic properties of the HSV-1 immediate-early ICPo protein. J. Gene Med. 7:1187-1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Bruyn Kops, A., S. L. Uprichard, M. Chen, and D. M. Knipe. 1998. Comparison of the intranuclear distributions of herpes simplex virus proteins involved in various viral functions. Virology 252:162-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Everett, R. D., G. Sourvinos, C. Leiper, J. B. Clements, and A. Orr. 2004. Formation of nuclear foci of the herpes simplex virus type 1 regulatory protein ICP4 at early times of infection: localization, dynamics, recruitment of ICP27, and evidence for the de novo induction of ND10-like complexes. J. Virol. 78:1903-1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Everett, R. D., G. Sourvinos, and A. Orr. 2003. Recruitment of herpes simplex virus type 1 transcriptional regulatory protein ICP4 into foci juxtaposed to ND10 in live, infected cells. J. Virol. 77:3680-3689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faber, S. W., and K. W. Wilcox. 1986. Association of the herpes simplex virus regulatory protein ICP4 with specific nucleotide sequences in DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 14:6067-6083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fraefel, C., A. G. Bittermann, H. Bueler, I. Heid, T. Bachi, and M. Ackermann. 2004. Spatial and temporal organization of adeno-associated virus DNA replication in live cells. J. Virol. 78:389-398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geoffroy, M. C., A. L. Epstein, E. Toublanc, P. Moullier, and A. Salvetti. 2004. Herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP0 protein mediates activation of adeno-associated virus type 2 rep gene expression from a latent integrated form. J. Virol. 78:10977-10986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glauser, D. L., M. Ackermann, O. Saydam, and C. Fraefel. 2006. Chimeric herpes simplex virus/adeno-associated virus amplicon vectors. Curr. Gene Ther. 6:315-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glauser, D. L., O. Saydam, N. A. Balsiger, I. Heid, R. M. Linden, M. Ackermann, and C. Fraefel. 2005. Four-dimensional visualization of the simultaneous activity of alternative adeno-associated virus replication origins. J. Virol. 79:12218-12230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grimm, D., A. Kern, K. Rittner, and J. A. Kleinschmidt. 1998. Novel tools for production and purification of recombinant adenoassociated virus vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 9:2745-2760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heilbronn, R., A. Burkle, S. Stephan, and H. zur Hausen. 1990. The adeno-associated virus rep gene suppresses herpes simplex virus-induced DNA amplification. J. Virol. 64:3012-3018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heilbronn, R., M. Engstler, S. Weger, A. Krahn, C. Schetter, and M. Boshart. 2003. ssDNA-dependent colocalization of adeno-associated virus Rep and herpes simplex virus ICP8 in nuclear replication domains. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:6206-6213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heister, T., I. Heid, M. Ackermann, and C. Fraefel. 2002. Herpes simplex virus type 1/adeno-associated virus hybrid vectors mediate site-specific integration at the adeno-associated virus preintegration site, AAVS1, on human chromosome 19. J. Virol. 76:7163-7173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson, P. A., M. J. Wang, and T. Friedmann. 1994. Improved cell survival by the reduction of immediate-early gene expression in replication-defective mutants of herpes simplex virus type 1 but not by mutation of the virion host shutoff function. J. Virol. 68:6347-6362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jurvansuu, J., K. Raj, A. Stasiak, and P. Beard. 2005. Viral transport of DNA damage that mimics a stalled replication fork. J. Virol. 79:569-580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knipe, D. M., D. Senechek, S. A. Rice, and J. L. Smith. 1987. Stages in the nuclear association of the herpes simplex virus transcriptional activator protein ICP4. J. Virol. 61:276-284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laughlin, C. A., J. D. Tratschin, H. Coon, and B. J. Carter. 1983. Cloning of infectious adeno-associated virus genomes in bacterial plasmids. Gene 23:65-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leung, A. K., and A. I. Lamond. 2002. In vivo analysis of NHPX reveals a novel nucleolar localization pathway involving a transient accumulation in splicing speckles. J. Cell Biol. 157:615-629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lilley, C. E., C. T. Carson, A. R. Muotri, F. H. Gage, and M. D. Weitzman. 2005. DNA repair proteins affect the lifecycle of herpes simplex virus 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:5844-5849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lukonis, C. J., J. Burkham, and S. K. Weller. 1997. Herpes simplex virus type 1 prereplicative sites are a heterogeneous population: only a subset are likely to be precursors to replication compartments. J. Virol. 71:4771-4781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCarty, D. M., S. M. Young, Jr., and R. J. Samulski. 2004. Integration of adeno-associated virus (AAV) and recombinant AAV vectors. Annu. Rev. Genet. 38:819-845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McLean, C., A. Buckmaster, D. Hancock, A. Buchan, A. Fuller, and A. Minson. 1982. Monoclonal antibodies to three non-glycosylated antigens of herpes simplex virus type 2. J. Gen. Virol. 63:297-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Michael, N., D. Spector, P. Mavromara-Nazos, T. M. Kristie, and B. Roizman. 1988. The DNA-binding properties of the major regulatory protein alpha 4 of herpes simplex viruses. Science 239:1531-1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muller, M. T. 1987. Binding of the herpes simplex virus immediate-early gene product ICP4 to its own transcription start site. J. Virol. 61:858-865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muzyczka, N., and K. I. Berns. 2001. Parvoviridae: the viruses and their replication, p. 2327-2346. In D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, D. E. Griffin, R. A. Lamb, M. A. Martin, B. Roizman, and S. E. Straus (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed., vol. 2. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raj, K., P. Ogston, and P. Beard. 2001. Virus-mediated killing of cells that lack p53 activity. Nature 412:914-917. (Erratum, 416:202, 2002.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Randall, R. E., and N. Dinwoodie. 1986. Intranuclear localization of herpes simplex virus immediate-early and delayed-early proteins: evidence that ICP 4 is associated with progeny virus DNA. J. Gen. Virol. 67:2163-2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saudan, P., J. Vlach, and P. Beard. 2000. Inhibition of S-phase progression by adeno-associated virus Rep78 protein is mediated by hypophosphorylated pRb. EMBO J. 19:4351-4361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slanina, H., S. Weger, N. D. Stow, A. Kuhrs, and R. Heilbronn. 2006. Role of the herpes simplex virus helicase-primase complex during adeno-associated virus DNA replication. J. Virol. 80:5241-5250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith, I. L., M. A. Hardwicke, and R. M. Sandri-Goldin. 1992. Evidence that the herpes simplex virus immediate early protein ICP27 acts post-transcriptionally during infection to regulate gene expression. Virology 186:74-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sourvinos, G., and R. D. Everett. 2002. Visualization of parental HSV-1 genomes and replication compartments in association with ND10 in live infected cells. EMBO J. 21:4989-4997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stracker, T. H., C. T. Carson, and M. D. Weitzman. 2002. Adenovirus oncoproteins inactivate the Mre11-Rad50-NBS1 DNA repair complex. Nature 418:348-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stracker, T. H., G. D. Cassell, P. Ward, Y. M. Loo, B. van Breukelen, S. D. Carrington-Lawrence, R. K. Hamatake, P. C. van der Vliet, S. K. Weller, T. Melendy, and M. D. Weitzman. 2004. The Rep protein of adeno-associated virus type 2 interacts with single-stranded DNA-binding proteins that enhance viral replication. J. Virol. 78:441-453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanaka, M., H. Kagawa, Y. Yamanashi, T. Sata, and Y. Kawaguchi. 2003. Construction of an excisable bacterial artificial chromosome containing a full-length infectious clone of herpes simplex virus type 1: viruses reconstituted from the clone exhibit wild-type properties in vitro and in vivo. J. Virol. 77:1382-1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taylor, T. J., M. A. Brockman, E. E. McNamee, and D. M. Knipe. 2002. Herpes simplex virus. Front. Biosci. 7:d752-d764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor, T. J., E. E. McNamee, C. Day, and D. M. Knipe. 2003. Herpes simplex virus replication compartments can form by coalescence of smaller compartments. Virology 309:232-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Timpe, J. M., K. C. Verrill, and J. P. Trempe. 2006. Effects of adeno-associated virus on adenovirus replication and gene expression during coinfection. J. Virol. 80:7807-7815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Trempe, J. P., E. Mendelson, and B. J. Carter. 1987. Characterization of adeno-associated virus Rep proteins in human cells by antibodies raised against Rep expressed in Escherichia coli. Virology 161:18-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsukamoto, T., N. Hashiguchi, S. M. Janicki, T. Tumbar, A. S. Belmont, and D. L. Spector. 2000. Visualization of gene activity in living cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:871-878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Uprichard, S. L., and D. M. Knipe. 1997. Assembly of herpes simplex virus replication proteins at two distinct intranuclear sites. Virology 229:113-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang, Y., S. M. Camp, M. Niwano, X. Shen, J. C. Bakowska, X. O. Breakefield, and P. D. Allen. 2002. Herpes simplex virus type 1/adeno-associated virus rep+ hybrid amplicon vector improves the stability of transgene expression in human cells by site-specific integration. J. Virol. 76:7150-7162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ward, P. L., and B. Roizman. 1994. Herpes simplex genes: the blueprint of a successful human pathogen. Trends Genet. 10:267-274. (Erratum, 10:380.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weindler, F. W., and R. Heilbronn. 1991. A subset of herpes simplex virus replication genes provides helper functions for productive adeno-associated virus replication. J. Virol. 65:2476-2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weitzman, M. D., K. J. Fisher, and J. M. Wilson. 1996. Recruitment of wild-type and recombinant adeno-associated virus into adenovirus replication centers. J. Virol. 70:1845-1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilkinson, D. E., and S. K. Weller. 2005. Inhibition of the herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA polymerase induces hyperphosphorylation of replication protein A and its accumulation at S-phase-specific sites of DNA damage during infection. J. Virol. 79:7162-7171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu, C. A., N. J. Nelson, D. J. McGeoch, and M. D. Challberg. 1988. Identification of herpes simplex virus type 1 genes required for origin-dependent DNA synthesis. J. Virol. 62:435-443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zolotukhin, S., B. J. Byrne, E. Mason, I. Zolotukhin, M. Potter, K. Chesnut, C. Summerford, R. J. Samulski, and N. Muzyczka. 1999. Recombinant adeno-associated virus purification using novel methods improves infectious titer and yield. Gene Ther. 6:973-985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]