Abstract

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) replication produces three envelope proteins (L, M, and S) that have a common C terminus. L, the largest, contains a domain, pre-S1, not present on M. Similarly M contains a domain, pre-S2, not present on S. The pre-S1 region has important functions in the HBV life cycle. Thus, as an approach to studying these roles, the pre-S1 and/or pre-S2 sequences of HBV (serotype adw2, genotype A) were expressed as N-terminal fusions to the Fc domain of a rabbit immunoglobulin G chain. Such proteins, known as immunoadhesins (IA), were highly expressed following transfection of cultured cells and, when the pre-S1 region was present, >80% were secreted. The IA were myristoylated at a glycine penultimate to the N terminus, although mutation studies showed that this modification was not needed for secretion. As few as 30 amino acids from the N terminus of pre-S1 were both necessary and sufficient to drive secretion of IA. Even expression of pre-S1 plus pre-S2, in the absence of an immunoglobulin chain, led to efficient secretion. Overall, these studies demonstrate an unexpected ability of the N terminus of pre-S1 to promote protein secretion. In addition, some of these secreted IA, at nanomolar concentrations, inhibited infection of primary human hepatocytes either by hepatitis delta virus (HDV), a subviral agent that uses HBV envelope proteins, or HBV. These IA have potential to be part of antiviral therapies against chronic HDV and HBV, and may help understand the attachment and entry mechanisms used by these important human pathogens.

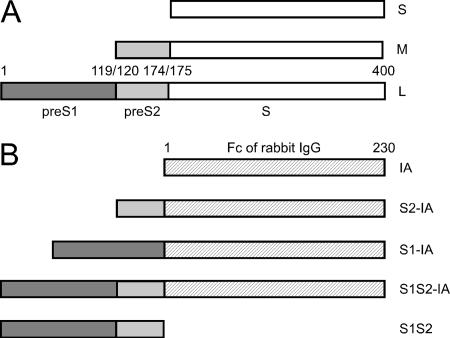

The predominant envelope protein of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and other hepadnaviruses is called S. As represented in Fig. 1A, HBV has two larger proteins (L and M) that are co-C-terminal with S. Pre-S2 is the sequence of M that is unique relative to S. Pre-S1 is the sequence of L that is unique relative to M. The N terminus of HBV pre-S1 contains a domain that is considered essential for an interaction between the virus and as yet unidentified host receptor(s) (1, 14, 17, 29). This region overlaps with one that can act as an endoplasmic reticulum (ER) retention signal (23), probably because it interacts with host molecular chaperones (11, 37).

FIG. 1.

HBV envelope proteins and construction of IA. Panel A is a representation of L, M, and S, the three HBsAg of the adw2 serotype of HBV. The pre-S1 and pre-S2 domains, along with the amino acid numbering are from GenBank accession no. AAK58874.1. Panel B shows the Fc region of a rabbit immunoglobulin G heavy chain and three IA that were constructed as N-terminal fusions with HBV pre-S sequences. Also shown is the free pre-S1 plus pre-S2 domain.

L, M, and S can be secreted from infected cells as subviral particles, although L alone can only be released when S is also present (10, 33). S protein alone is sufficient for N glycosylation and secretion (3). All three proteins undergo some level of N or O glycosylation prior to release, consistent with their transport through the ER and Golgi apparatus (15). L is myristoylated at a glycine penultimate to the N-terminal methionine (34). This modification is not essential for assembly, but it is required for infectivity (4, 18). The pre-S domains of L can exist in two quite different topological conformations, due to posttranslational translocation across the ER membrane (5, 32, 35). It has been shown that sequences within S act as a signal for pre-S2 translocation of M (13). Furthermore, it has been assumed that sequences within S also direct the translocation of upstream sequences in the L protein (25). Consequently, for L and M, it has been assumed that the pre-S1 and pre-S2 domains, respectively, do not contain any translocation signal. As a direct test of this interpretation, previous studies have attempted to fuse the pre-S1 plus pre-S2 domains to a reporter protein and were unable to detect translocation into ER-derived microsomes (32). In contrast, the studies presented here provide evidence that pre-S sequences can direct protein secretion.

Our strategy was to test the roles of pre-S1 and pre-S2 via the formation of immunoadhesins (IA) (7, 8). As represented in Fig. 1B, these IA were created by using the C-terminal constant domains of a rabbit immunoglobulin G heavy chain and fusing to the N terminus various forms of HBV pre-S1 and/or pre-S2. As reported here, we found that the created IA were efficiently expressed and some were efficiently secreted. Our findings have implications for the general field of protein secretion and perhaps also for secretion of HBV particles. In addition, we report that some of the secreted IA were able to block virus infection. Thus, such IA have potential applications as antivirals and for characterizing the as yet unidentified host proteins that interact with the HBV envelope during virus attachment and entry.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Human embryonic kidney 293T, T-Rex, and human hepatoblastoma Huh7 cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. Primary human hepatocytes in a 48-well configuration plated as confluent monolayers on rat tail collagen were obtained commercially (Admet, Cambrex, or CellzDirect) and maintained in Hepatostim medium supplemented with 0.01 μg/ml epidermal growth factor, receptor grade, both from BD Biosciences. All cells were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2. Hepatitis delta virus (HDV) and HBV were assembled in vitro from transfected cells, as previously described (20).

IA construction and expression.

Unless otherwise stated, the HBV nucleotide sequences were for serotype adw2, genotype A (GenBank accession no. ΔF305422). Vector constructions were as described by Chai and Bates (7). Briefly, various pre-S regions were amplified using specific primers and PCR. These were inserted into plasmid pCAGGS-rIg, kindly provided by Rachel Kaletsky and Paul Bates. Additional point mutations were created using a QuikChange kit (Stratagene). Constructs were transfected into 293T cells using calcium phosphate or into Huh7 cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). The media were supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum that had been depleted of immunoglobulin G (Invitrogen). After 2 days, the media were harvested and clarified, while the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and then lysed in 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). T-REx 293 cell lines (Invitrogen) conditionally expressing IA were created using procedures previously described (9).

Immunoblot procedures.

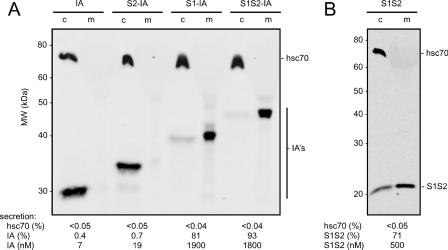

Samples were boiled in Laemmli buffer, with or without dithiothreitol, prior to analysis on 12% precast Duramide gels (Cambrex). After electrophoresis and transfer to nitrocellulose membranes, IA were detected using infrared dye-labeled goat anti-rabbit antibody (LI-COR). The hsc70 was detected on the same membrane using a primary mouse monoclonal antibody (Affinity Bioreagents) followed by a goat anti-mouse antibody labeled with a different infrared dye (LI-COR). Molecules containing the HBV pre-S2 domain were detected using S-26, a mouse monoclonal, as the primary antibody (as described elsewhere [39], a gift from Vadim Bichko). Similarly, molecules containing pre-S1 were detected using Ma18/7, another mouse monoclonal (as described elsewhere [21], a gift from Wolfram Gerlich). Detection and quantitation were achieved using a two-color infrared laser-scanning apparatus and associated software (Odyssey; LI-COR). This system has the advantage of a linear response over a >4,000-fold range. To determine the molar concentration of secreted pre-S for each of the IA fusion proteins, the immunoblot data, as shown in Fig. 2A, were normalized to known amounts of a protein A affinity-purified IA (7). Such data were then used to normalize the amounts of the nonfusion protein S1S2, using immunoblot data as shown in Fig. 2B.

FIG. 2.

Immunoblot detection and quantitation of IA and S1S2 protein. The domains indicated in Fig. 1B were assembled in an expression vector under control of a β-actin promoter. Two days after transfection into 293T cells, both media and cell samples, as indicated by “c” and “m,” respectively, were examined by immunoblot. In panel A, the four IA were detected via a dye-labeled goat anti-rabbit antibody. In panel B, the S1S2 protein was detected via S-26, a mouse monoclonal antibody specific for the HBV pre-S2 domain. In both panels, hsc70 was detected via a mouse monoclonal antibody.

Radioactive labeling of IA.

Soon after transient transfection, cells were washed and then incubated with media containing [3H]myristic acid (10 μCi/ml; New England Nuclear). After 2 days, the media and cells were harvested as described above. IA were selected by binding to protein A-agarose (Invitrogen) and then subjected to electrophoresis and electrotransfer to a nitrocellulose membrane. The 3H on the dried membrane was detected and quantitated with a special screen and bio-imager (Fujifilm BAS-2400). Then the membrane was subjected to immunoblotting to detect IA, as described above.

Biological activity.

To test inhibitory activity of the IA and related proteins, we used primary human hepatocytes infected in the presence of 5% polyethylene glycol 8000 (Sigma) with in vitro-assembled HDV at a multiplicity of 10 genome equivalents per cell or by HBV at a multiplicity of 50 genome equivalents/cell, using procedures as previously described (20). Unless stated otherwise, the IA and related proteins were only present during the 16-h infection period. One related protein was the S1S2, lacking the Fc domain (Fig. 1B). Another was a synthetic peptide corresponding to positions 2 to 48 of the ayw pre-S1, with myristoylation at the N-terminal glycine (as described elsewhere [14], a kind gift from Stephan Urban). After 7 to 8 days, total cell RNA was extracted, and HDV antigenomic RNA and HBV RNA were quantitated using real-time PCR.

RESULTS

Design, transient expression, and secretion of IA with HBV pre-S sequences.

Our initial studies involved the expression of the four IA diagrammed in Fig. 1B. These are fusions of HBV pre-S sequences to the Fc region of a rabbit immunoglobulin G. Two days after transient transfection into 293T cells, a line of human embryonic kidney cells, aliquots of the total cell proteins and the tissue culture media were examined by immunoblotting for the presence of IA, using dye-labeled goat anti-rabbit antibody. The results, with quantitation, are shown in Fig. 2A. All four IA were expressed in transfected cells. However, they differed in terms of secretion. The IA without HBV sequences was not secreted, consistent with the lack of a signal peptide. The S2-IA was also not secreted. This supports the reported interpretation that pre-S2 does not contain a signal activity (13). S1-IA and S1S2-IA were efficiently secreted, with >80% of the total IA being present in the medium. (It should be understood that the % secretion as measured here is really the steady-state distribution of the protein in the media relative to the sum of the accumulations in the cells and media.)

These results support the interpretation that pre-S1 contains significant secretion-directing activity and that the presence of pre-S2 has no negative effect on this ability. While these experiments were performed in 293T cells, we obtained comparable results for expression and secretion of IA in Huh7, a human hepatoblastoma cell line (data not shown).

It should be noted that with S1-IA and S1S2-IA, the concentration accumulated in the media during just 2 days was determined to be as high as 1,800 nM (about 80 μg/ml). Furthermore, it can be deduced that, in this period, the average cell expressed 700 million IA molecules, and this is a lower estimate that does not allow for the efficiency of DNA transfection or for posttranslational protein turnover.

As an internal negative control for secretion, we assayed each sample for hsc70, an abundant host protein that is also known to interact with a domain of HBV pre-S1 in the cytosol (28). No hsc70 was detected in the media (Fig. 2A). As an additional control, β-actin was not released into the media (data not shown). Thus, the integrity of the transfected cells was not compromised by either the transfection or the abundant expression and secretion of the IA.

In addition, we tested whether the released IA was actually a soluble protein. Media samples containing bovine serum albumin and secreted S1S2-IA were clarified by low-speed centrifugation and then subjected to ultracentrifugation (4 h, 41 krpm, 288,000 × g), conditions that pellet HDV and HBV subviral particles. We thus observed that <5% of the albumin and S1S2-IA were pelleted (data not shown). Thus, we interpret the IA as behaving like albumin, that is, as a soluble protein.

The above studies indicated that pre-S1 plus pre-S2 or just pre-S1 was sufficient to direct IA secretion. This was an unexpected result, since others observed that the pre-S sequences of HBV L were unable to direct the translocation of a fusion protein with globin into ER-derived microsomes and thus concluded that no signal sequence was present in pre-S (32).

Secretion in the absence of the Fc domain.

Even though the Fc domain alone was not secreted (Fig. 2A), it could have contained a cryptic secretion signal that was somehow activated by the fusion of pre-S sequences. Therefore, we tested the expression of pre-S1 plus pre-S2 in the absence of the Fc domain. This 174-amino-acid protein, S1S2, was detected using a mouse monoclonal antibody specific for an epitope in pre-S2. The results, with quantitation, are shown in Fig. 2B. More than 70% of this protein was secreted into the medium. The pre-S1 domain in the absences of IA was expressed and secreted, but the intracellular accumulation was poor (data not shown).

Since the 174 amino acids of S1S2 were sufficient for secretion, this excludes the possibility that secretion of IA species might be via a cryptic signal within the Fc domain.

Minimal sequences needed for IA secretion.

To determine the minimal sequences necessary for secretion, we tested a series of truncations of pre-S1 sequences. For this, we returned to the strategy of using IA fusions. This strategy made it possible to readily separate and quantitate the expression and secretion of IA fused to altered pre-S sequences. As summarized in Table 1, we found that truncations of pre-S1 down to the 30 N-terminal amino acids still gave efficient secretion (75%). Ten N-terminal amino acids also gave secretion, but it was much less efficient (4%). Thus, the first 30 amino acids were sufficient for efficient secretion. As a control for this interpretation, we made an IA fusion that contained an N-terminal methionine and then only the sequences from position 31 to the C terminus of pre-S2. This protein was expressed but not secreted (Table 1). Thus, the first 30 amino acids are both necessary and sufficient. Again, we extended these results from 293T cells to Huh7 cells and obtained comparable results (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Effect of alterations in the pre-S domains on the efficiency of IA secretiona

| Domain | pre-S sequence expressed as IA | % Secretion |

|---|---|---|

| Trimmed domains | ||

| 1-59 | MGGWSSKPRKGMGTNLSVPNPLGFFPDHQLDPAFGANSNNPDWDFNPIKDHWPAANQVG | 68 |

| 1-30 | MGGWSSKPRKGMGTNLSVPNPLGFFPDHQL | 75 |

| 1-10 | MGGWSSKPRK | 4 |

| 1, 31-174 | MDPAFGANSNNPDWDFNPIKDHWPAANQVG . . . . . . PVTN | 0.3 |

| Mutated 1-119 domain of S1-IA | ||

| G2A, G13A | MAGWSSKPRKGMATNLSVPNPLGFFPDHQLD . . . . . . HPQA | 71 |

| N15Q | MGGWSSKPRKGMGTQLSVPNPLGFFPDHQLD . . . . . . HPQA | 64 |

The sequences are those of serotype adw2 (GenBank accession no. AAK58874.1). The amino acid replacements are underlined. Immunoblot quantitation was as shown in Fig. 2A. Data are expressed as percentages of IA detected in medium relative to total in medium and cells.

In the above studies, the HBV envelope sequences used were those of the adw2 serotype. Another commonly studied serotype is ayw. In terms of the pre-S1 domain, ayw differs in that it is 11 amino acids shorter at the N terminus. Moreover, in the next 48 amino acids that have homology to the adw2, there are 10 amino acid changes. Nevertheless, when these 48 amino acids from the pre-S1 domain of ayw were expressed as an IA, we observed efficient secretion (79%) (data not shown). Apparently, the above-mentioned differences in the N-terminal pre-S1 sequence did not interfere with secretion.

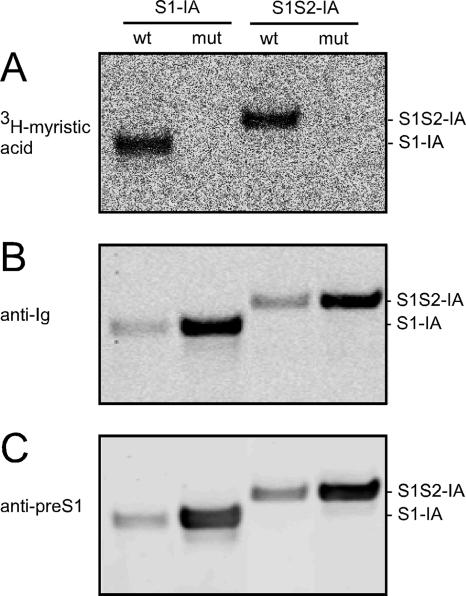

Posttranslational modifications of IA.

Since only 30 amino acids of pre-S1 were needed for secretion, we sought to determine whether some posttranslational modifications of this sequence were necessary. Initially, we tested for myristoylation, since it is known that during HBV replication the glycine penultimate to the N terminus of pre-S1 undergoes myristoylation (34) and this modification is needed for HBV infectivity but not for assembly (4, 18). We therefore mutated this penultimate glycine, as well as the next glycine, at position 13. We checked this second glycine because it follows a methionine that might theoretically be a secondary site for the initiation of translation. Such glycine changes did not interfere with secretion of S1-IA (Table 1). Similar results were obtained for S1S2-IA (data not shown).

Furthermore, to confirm that myristoylation was occurring on the wild-type (wt) IA but blocked on the mutated forms, we tested both proteins for their ability to be labeled with [3H]myristic acid. As shown in Fig. 3A, only the wt forms of S1-IA and S1S2-IA were labeled. These assays, however, did not tell to what extent myristoylation occurred. We then used the same membrane and performed immunoblots with detection via the Fc domain (Fig. 3B) and via the pre-S1 region (Fig. 3C). These results confirmed that the mutant proteins were efficiently expressed but not myristoylated. In addition, the 3H-labeled forms of S1-IA and S1S2-IA were secreted into the media, and the extent of secretion of the myristoylated protein detected by 3H was not less than that of the total IA detected by immunoblotting (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Incorporation of [3H]myristic acid into IA. 293T cells were transfected with vectors that express S1-IA or S1S2-IA, either as wt or mutant (mut) at the two glycines near the N terminus. After 2 days in the presence of [3H]myristic acid and reduced serum, the cells were extracted and immunoselected using protein A-agarose. The selected materials were subjected to polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and electrotransfer to a nitrocellulose membrane. Panel A shows the detection of 3H on the membrane. Panel B shows the results when this same filter was then subjected to immunoblotting with a dye-labeled goat anti-rabbit antibody to detect IA. Panel C is an immunoblot with a monoclonal antibody Ma18/7, directed at an epitope within the pre-S1 region. As can be seen from panels B and C, the amounts of mutated proteins examined were made greater than those for the wt. This was done to accentuate that the mutated proteins lack detectable 3H labeling.

A second possible posttranslational modification of the 30 amino acids was glycosylation. Specifically, previous studies have reported a cryptic N glycosylation site at position 15 (6). We mutated this asparagine to glutamine on S1-IA and found that it had no effect on secretion (Table 1). Similar results were obtained for S1S2-IA (data not shown). These results are consistent with our inability to detect a glycosylated form of IA.

IA dimerization.

Immunoadhesins are able to form dimers through disulfide linkages in the immunoglobulin domain (8). To test for this, we examined by electrophoresis under nonreducing conditions the secreted S1-IA and S1S2-IA, and observed 14% as dimers (data not shown). Thus, we interpret that while some dimers were formed, such formation was not essential for secretion to occur.

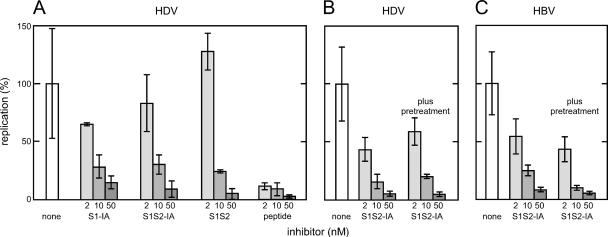

Certain IA can inhibit infection by HDV and HBV.

Others have shown that peptides based on the N terminus of HBV pre-S1 are able to interfere with infection of primary hepatocytes and of HepaRG cells, a cell line made from a differentiated liver tumor (17, 19). Furthermore, it is known that such inhibition ability is potently enhanced by the presence of the N-terminal myristoylation (17). We therefore tested some of our secreted IA for their ability to interfere with the infection of primary human hepatocytes by HDV (20). For these studies, the source of IA was simple dilutions of the media from transiently transfected cells that both expressed and secreted the IA. To assess HDV replication, the total RNA was extracted after 7 days and antigenomic RNA was quantitated by real-time PCR. A major advantage of measuring antigenomic rather than genomic RNA is that it eliminates what might be a residual signal of viral (genomic) RNA that somehow binds to the monolayer culture but does not undergo genome replication.

Our results are summarized in Fig. 4A. At a 50 nM final concentration, S1-IA and S1S2-IA both gave about 90% inhibition. The S1S2 peptide, without the IA domain, was even more potent in inhibition (Fig. 4). However, neither the IA with only 59 amino acids from the N terminus of pre-S1 nor the mutated S1-IA that was not myristoylated was able to inhibit significantly, that is, less than a twofold effect at 50 nM (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Ability of IA and related proteins to inhibit infection by HDV and HBV of primary human hepatocytes. For panel A, the IA expressed in 293T cells and secreted into the media were quantitated. Then aliquots of these media were used at three concentrations in assays for their effect on the ability of HDV to infect primary human hepatocytes. A comparison was made with respect to S1S2, which lacks the IA domain, and a myristoylated synthetic peptide corresponding to the N terminus of HBV ayw PreS1. The concentrations used were 2, 10, and 50 nM, as indicated by increasing shades of gray. The vertical axis expresses in arbitrary units the amount of antigenomic HDV RNA per infected cell, as determined by quantitative real-time PCR. Indicated are average values with standard deviations of results from independent infections. In panel B, S1S2-IA was tested for its effects on HDV infection of hepatocytes, either without or with a 30-min pretreatment, in addition to the treatment during infection. Panel C shows an experiment carried out in parallel with that of panel B, except that HDV was replaced by HBV, and the real-time PCR assays were for HBV RNA.

Engelke et al. (14) recently reported that acylated glutathione S-transferase fusion proteins with amino acids 2 to 48 of an HBV pre-S1 could inhibit infection of primary human hepatocytes and HepaRG cells by HBV and HDV. Previously, Gripon et al. reported the use of acylated synthetic peptides to inhibit HBV infection (19). As shown in Fig. 4, we compared one such acylated peptide (a kind gift from Stephan Urban) with the inhibition obtained using S1-IA or S1S2-IA. As shown, this peptide gave more inhibition than the two IA. It should be noted that the synthetic peptide was both myristoylated and purified. Its sequence was based on another serotype of HBV (ayw) and, as mentioned earlier, differs in sequence from that used both for the IA and for the assembly of infectious HDV (adw2).

In other experiments, we examined whether addition of the inhibitors not only at the time of infection but also during the 30 min prior to infection would increase the level of inhibition. As summarized in Fig. 4B, the pretreatment with S1S2-IA did not significantly increase the level of inhibition relative to cells that were not pretreated.

In parallel with the experiment shown in Fig. 4B, we determined whether S1S2-IA would also act on HBV infection. As summarized in Fig. 4C, there was inhibition. Moreover, the results were similar to the inhibition observed for HDV infection. This further supports the interpretation that HDV and HBV use the same entry mechanism on primary hepatocytes.

Effects of extent and mode of expression on S1S2-IA secretion.

Finally, we returned to the question of how the S1S2-IA is secreted. The studies described so far showed that myristoylation was not needed. Also, the transfection procedure and the abundant intracellular expression did not lead to the release of IA lacking pre-S1 sequences or of the host proteins hsc70 and β-actin.

To test the remaining possibility that overexpression of the pre-S sequence was somehow required for secretion, we decreased the amount of the S1S2-IA DNA construct used for transient transfection by 64-fold. This reduced the protein expression by 20-fold and yet the secretion was still >80% (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Effect of S1S2-IA expression level on secretion

| Mechanism for achieving IA expressiona | % Secretionb | Concn (nM) in mediab |

|---|---|---|

| Transient transfection with 10 μg of plasmid | 95 | 540 |

| Transient transfection with 0.16 μg of plasmid | 83 | 26 |

| Induced expression from a stable cell line | 82 | 320 |

Transient transfection of 293T cells was with plasmid expressing S1S2-IA. The stable cell line was T-REx 293 containing a single copy of the S1S2-IA cDNA under control of a tetracycline-inducible promoter.

Percent secretion and concentration in media were determined as described for Fig. 2 and measured 2 days after either transfection or tetracycline induction.

As an additional approach to exclude the possibility that the transient-transfection procedure somehow contributed to the observed secretion, we established a stable T-REx 293 cell line, containing a single copy of the S1S2-IA sequence per cell, with expression under TET-on control (9). We found, as in the other studies, that the secretion was >80% (Table 2). Similar results were obtained with a cell line expressing S1-IA (data not shown). The results with the stable cell line tell us that even in the absence of a transfection procedure, IA was efficiently secreted. A separate advantage of the cell line is that it provides a stable source of secreted IA.

DISCUSSION

Two main issues for discussion arise from this study. First, how do pre-S1 sequences direct efficient secretion and second, what future applications can be made of the observation that IA such as S1S2-IA are potent inhibitors of HDV and HBV infection?

Before discussing pre-S1-directed secretion of IA, there is an important caveat. It is that this secretion may have some significant differences relative to what happens when pre-S1, in the context of pre-S2 and S, translocates the ER membrane as part of the assembly and release of naturally occurring forms that contain multimers, such as the empty virus-like particles or the nucleocapsid-containing HBV and HDV. A negative effect of multimerization is that, in the absence of S, the L protein forms intracellular particles but they are not secreted (43).

We first determined that for the efficient secretion of IA, 30 amino acids from the N terminus of pre-S1 were both necessary and sufficient (Table 1). This secretion signal was probably not cleaved off because N-terminal myristoylation was detected on full-length IA (Fig. 3A), although myristoylation itself was not necessary for secretion (Table 1). We note that it is known that HBV assembly and release is also not dependent upon myristoylation, even though this modification is essential for infectivity (4, 18). Next, we sought to determine whether N glycosylation was involved, since it is controversial as to whether this is needed for assembly and secretion of virus-like particles (40, 42). In particular, others have suggested that an asparagine at position 15 from the N terminus could be glycosylated (6). We mutated this amino acid and detected no change in secretion (Table 1), leading us to interpret that glycosylation at least at this site was not necessary. In addition, when tunicamycin was added soon after transient transfection, we detected no inhibition of secretion (data not shown), further supporting the interpretation that no N-linked glycosylation was necessary. Finally, we tested whether overexpression of the IA somehow contributed to the efficient secretion. We observed that after reducing the transient expression level 20-fold or by avoiding transfection and using inducible expression from an integrated cDNA, we still obtained >80% secretion of the S1S1-IA (Table 2). How then was the efficient secretion obtained?

The mechanism of protein secretion can be divided into two major pathways: the classical ER-Golgi-dependent pathway and the unconventional pathway. Proteins using the classical pathway can translocate across the ER membrane either cotranslationally or posttranslationally, largely dependent on whether a hydrophobic signal peptide is present (22). HBV pre-S lacks a predicted N-terminal signal peptide. Also, the presence of myristoylation on pre-S (and the pre-S IA) argues against the removal of such a putative sequence. The pre-S is thought to translocate the ER membrane posttranslationally (5, 32, 35). Accordingly, pre-S IA might be secreted through posttranslational translocation into the ER lumen. We observed a low level of IA dimerization and are not sure whether this reflects translocation into an ER subdomain with reduced oxidation activity. Nonetheless, an alternative secretory pathway of pre-S IA might be direct translocation across the plasma membrane, the unconventional pathway. Proteins using this pathway lack a typical signal peptide and are secreted through various mechanisms (30, 31). Although very limited information is available about motifs directing unconventional protein secretion, a few such sequences have been determined. They do not share homology, but most of them are located at the N terminus. One of them, like the pre-S1, is myristyolated at a glycine residue in position 2 (12). It will be interesting to test whether the HBV pre-S secretion signal we identified can functionally replace those motifs in directing protein secretion.

Relevant to the secretion mechanism and its regulation is that one or more host chaperones may bind to the short pre-S1 region. One candidate comes from a recent report that the HBV pre-S1 domain interacts with nascent polypeptide-associated complex α polypeptide (27). This protein is known to form a tight dimer with a second protein, nascent polypeptide-associated complex β polypeptide, bind to ribosomes, and make the first contact in the cytosol of nascent polypeptide chains. It can contribute to whether proteins lacking a signal sequence do or do not become targeted to the ER (2). A second candidate is hsc70, which is known to act as a cytosolic chaperone for pre-S (24, 28). If the pre-S IA actually enter the ER, then another candidate interacting protein is BiP, a resident ER chaperone, for which there is already evidence that it binds to HBV pre-S1 (11, 37). Future studies will use the IA described here to better characterize the host proteins involved in their secretion and to what extent the mechanisms apply to the topogenesis and intracellular transport of HBV envelope proteins.

The second question arising from this study is the potential applications of such secreted IA species that can inhibit HDV and HBV infection (Fig. 4). One application would be as part of a combination antiviral therapy. For example, while nucleoside inhibitors such as entecavir (Baraclude; Bristol-Myers Squibb) can suppress HBV levels in serum of patients chronically infected with HBV by 100,000-fold (38), the infection is nevertheless not cleared and over time there can emerge drug-resistant mutants (36). The IA described here are based on fusions to a rabbit immunoglobulin, but this could readily be changed to a human sequence. Indeed, many human IA expressing other protein sequences have been described. For example, etanercept (Enbrel; Amgen/Immunex) expresses part of the tumor necrosis factor alpha receptor and is widely used in patients as an anti-inflammatory treatment. IA are known to have unique advantages in that they have increased in vivo stability (8). There are several examples of IA that have been derived either from envelope sequences of other viruses, such as human immunodeficiency virus, or their receptors (7, 41). While we show that the HBV IA are secreted efficiently (Fig. 2; Table 1) and are biologically active without further purification (Fig. 4), it should be noted that, as part of an antiviral therapy, the IA could be prepurified in a single step of protein A binding and elution. Alternatively, the IA could be delivered indirectly, for example, from a cDNA construct, or expressed from a viral vector, such as a lentivirus (26) or adeno-associated virus (16). Further experiments will be needed to test whether such potential can be realized.

Some comments need to be made regarding the advantages and disadvantages of IA relative to short myristoylated pre-S1 peptides. The latter have already been shown by others to inhibit infection of hepatocytes by HBV and HDV (1, 14, 17). We confirmed these findings for HDV and found that S1-IA, S1S2-IA, and S1S2 were inhibitory but not as potent as the myristoylated 48-amino-acid peptide (Fig. 4). Gripon et al. have reported that when this peptide was increased to 68 amino acids in length, the ability to inhibit infection was reduced 10-fold (17). Maybe this increase in length leads to intramolecular folding that hides the inhibitory activity. A second form of steric hindrance seems peculiar to the IA constructs, in that 59 amino acids from the N terminus of pre-S1 when fused to IA were efficiently secreted but unable to inhibit HDV infection. This could be a consequence of the Fc domain interfering with the access of the N terminal inhibitory sequence to the host receptor(s). This interpretation could be tested by varying the distance between the N-terminal inhibitory sequence and the Fc domain. Yet a third form of hindrance associated with added size of the IA might be a decreased accessibility to the as yet unidentified target receptor(s), either at the surface of the host cell or even within some endosomal compartment. However, for an in vivo situation, the larger size of the IA and their dimerization might confer the compensating advantage of higher stability.

Finally, another application of the IA is in terms of understanding the mechanism by which HDV and HBV attach to and enter human hepatocytes. A precedent for this strategy is the recent isolation and identification of the receptor for an avian leukosis virus (7).

Acknowledgments

J.T. was supported by grants AI-058269 and CA-06927 from the NIH and by an appropriation from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. This project was conceived by N.C., who was supported in part by the Elizabeth Knight Patterson Fellowship.

Stephan Urban, Volker Bruss, William Mason, and Glenn Rall provided constructive comments on the manuscript. We thank Emmanuelle Nicolas and the Fox Chase Biochemistry and Biotechnology Facility for the real-time PCR assays.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 28 February 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barrera, A., B. Guerra, L. Notvall, and R. E. Lanford. 2005. Mapping of the hepatitis B virus pre-S1 domain involved in receptor recognition. J. Virol. 79:9786-9798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beatrix, B., H. Sakai, and M. Wiedmann. 2000. The alpha and beta subunit of the nascent polypeptide-associated complex have distinct functions. J. Biol. Chem. 275:37838-37845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruss, V., and D. Ganem. 1991. The role of envelope proteins in hepatitis B virus assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:1059-1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruss, V., J. Hagelstein, E. Gerhardt, and P. R. Galle. 1996. Myristylation of the large surface protein is required for hepatitis B virus in vitro infectivity. Virology 218:396-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruss, V., X. Lu, R. Thomssen, and W. H. Gerlich. 1994. Post-translational alterations in transmembrane topology of the hepatitis B virus large envelope protein. EMBO J. 13:2273-2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruss, V., and K. Vieluf. 1995. Functions of the internal pre-S domain of the large surface protein in hepatitis B virus particle morphogenesis. J. Virol. 69:6652-6657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chai, N., and P. Bates. 2006. Na+/H+ exchanger type 1 is a receptor for pathogenic subgroup J avian leukosis virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:5531-5536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chamow, S. M., and A. Ashkenazi. 1996. Immunoadhesins: principles and applications. Trends Biotechnol. 14:52-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang, J., S. O. Gudima, C. Tarn, X. Nie, and J. M. Taylor. 2005. Development of a novel system to study hepatitis delta virus genome replication. J. Virol. 79:8182-8188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng, C., K. Smith, and B. Moss. 1986. Hepatitis B large surface protein is not secreted but is immunogenic when selectively expressed by recombinant vaccinia virus. J. Virol. 60:337-344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho, D. Y., G. H. Yang, C. J. Ryu, and H. J. Hong. 2003. Molecular chaperone GRP78/BiP interacts with the large surface protein of hepatitis B virus in vitro and in vivo. J. Virol. 77:2784-2788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denny, P. W., S. Gokool, D. G. Russell, M. C. Field, and D. F. Smith. 2000. Acylation-dependent protein export in Leishmania. J. Biol. Chem. 275:11017-11025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eble, B. E., V. R. Lingappa, and D. Ganem. 1990. The N-terminal (pre-S2) domain of a hepatitis B virus surface glycoprotein is translocated across membranes by downstream signal sequences. J. Virol. 64:1414-1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engelke, M., K. Mills, S. Seitz, P. Simon, P. Gripon, M. Schnolzer, and S. Urban. 2006. Characterization of a hepatitis B and hepatitis delta virus receptor binding site. Hepatology 43:750-760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerlich, W. H., and M. Kann. 2005. Hepatitis B, p. 1226-1268. In B. W. J. Mahy and V. ter Meulen (ed.), Topley and Wilson's microbiology and microbial infections, vol. 2. ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grimm, D., K. Pandey, H. Nakai, T. A. Storm, and M. A. Kay. 2006. Liver transduction with recombinant adeno-associated virus is primarily restricted by capsid serotype not vector genotype. J. Virol. 80:426-439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gripon, P., I. Cannie, and S. Urban. 2005. Efficient inhibition of hepatitis B virus infection by acylated peptides derived from the large viral surface protein. J. Virol. 79:1613-1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gripon, P., J. Le Seyec, S. Rumin, and C. Guguen-Guillouzo. 1995. Myristylation of the hepatitis B virus large surface protein is essential for viral infectivity. Virology 213:292-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gripon, P., S. Rumin, S. Urban, J. Le Seyec, D. Glaise, I. Cannie, C. Guyomard, J. Lucas, C. Trepo, and C. Guguen-Guillouzo. 2002. Infection of a human hepatoma cell line by hepatitis B virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:15655-15660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gudima, S., Y. He, A. Meier, J. Chang, R. Chen, M. Jarnik, E. Nicolas, V. Bruss, and J. Taylor. 2007. Assembly of hepatitis delta virus: particle characterization including ability to infect primary human hepatocytes. J. Virol. 81:3608-3617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heermann, K. H., F. Kruse, M. Seifer, and W. H. Gerlich. 1987. Immunogenicity of the gene S and Pre-S domains in hepatitis B virions and HBsAg filaments. Intervirology 28:14-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalies, K. U., and E. Hartmann. 1998. Protein translocation into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-two similar routes with different modes. Eur. J. Biochem. 254:1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuroki, K., R. Russnak, and D. Ganem. 1989. Novel N-terminal amino acid sequence required for retention of a hepatitis B virus glycoprotein in the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol. Cell. Biol. 9:4459-4466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lambert, C., and R. Prange. 2003. Chaperone action in the posttranslational topological reorientation of the hepatitis B virus large envelope protein: implications for translocational regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:5199-5204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lambert, C., and R. Prange. 2001. Dual topology of the hepatitis B virus large envelope protein: determinants influencing post-translational pre-S translocation. J. Biol. Chem. 276:22265-22272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levine, B. L., L. M. Humeau, J. Boyer, R. R. Macgregor, T. Rebello, X. Lu, G. K. Binder, V. Slepushkin, F. Lemiale, J. R. Mascola, F. D. Bushman, B. Dropulic, and C. H. June. 2006. Gene transfer in humans using a conditionally replicating lentiviral vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:17373-17377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, D., X. Z. Wang, J. Ding, and J.-P. Yu. 2005. NACA as a potential cellular target of hepatitis B virus preS1 protein. Dig. Dis. Sci. 50:1156-1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loffler-Mary, H., M. Werr, and R. Prange. 1997. Sequence-specific repression of cotranslational translocation of the hepatitis B virus envelope proteins coincides with binding of heat shock protein Hsc70. Virology 235:144-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neurath, A. R., S. B. H. Kent, N. Strick, and K. Parker. 1986. Identification and chemical synthesis of a host cell receptor binding site on hepatitis B virus. Cell 46:429-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nickel, W. 2003. The mystery of nonclassical protein secretion. A current view on cargo proteins and potential export routes. Eur. J. Biochem. 270:2109-2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nickel, W. 2005. Unconventional secretory routes: direct protein export across the plasma membrane of mammalian cells. Traffic 6:607-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ostapchuk, P., P. Hearing, and D. Ganem. 1994. A dramatic shift in the transmembrane topology of a viral envelope glycoprotein accompanies hepatitis B viral morphogenesis. EMBO J. 13:1048-1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Persing, D. H., H. E. Varmus, and D. Ganem. 1986. Inhibition of secretion of hepatitis B surface antigen by a related presurface polypeptide. Science 234:1388-1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Persing, D. H., H. E. Varmus, and D. Ganem. 1987. The preS1 protein of hepatitis B virus is acylated at its amino terminus with myristic acid. J. Virol. 61:1672-1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prange, R., and R. E. Streeck. 1995. Novel transmembrane topology of the hepatitis B virus envelope proteins. EMBO J. 14:247-256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Revill, P., and S. Locarnini. 2006. The clinical virology of hepatitis B. Future Virol. 1:349-360. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ryu, C. J., D. Y. Cho, P. Gripon, H. S. Kim, C. Guguen-Guillouzo, and H. J. Hong. 2000. An 80-kilodalton protein that binds to the pre-S1 domain of hepatitis B virus. J. Virol. 74:110-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schreibman, I. R., and E. R. Schiff. 2006. Entacivir: a new treatment for chronic hepatitis B infection. Future Virol. 1:541-552. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sominskaya, I., V. Bichko, P. Pushko, A. Dreimane, D. Snikere, and P. Pumpens. 1992. Tetrapeptide QDPR is a minimal immunodomonant epitope within the preS2 domain of hepatitis B virus. Immunol. Lett. 33:169-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sureau, C., C. Fournier-Wirth, and P. Maurel. 2003. Role of N glycosylation of hepatitis B virus envelope proteins in morphogenesis and infectivity of hepatitis delta virus. J. Virol. 77:5519-5523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ward, R. H., D. J. Capon, C. M. Jett, K. K. Murthy, J. Mordenti, C. Lucas, S. W. Frie, A. M. Prince, J. D. Green, and J. W. Eichberg. 1991. Prevention of HIV-1 IIIB infection in chimpanzees by CD4 immunoadhesin. Nature 352:434-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Werr, M., and R. Prange. 1998. Role for calnexin and N-linked glycosylation in the assembly and secretion of hepatitis B virus middle envelope protein particles. J. Virol. 72:778-782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu, Z., V. Bruss, and T. S. Yen. 1997. Formation of intracellular particles by hepatitis B virus large surface protein. J. Virol. 71:5487-5494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]