Abstract

The exposure of molecular signals for simian virus 40 (SV40) cell entry and nuclear entry has been postulated to involve calcium coordination at two sites on the capsid made of Vp1. The role of calcium-binding site 2 in SV40 infection was examined by analyzing four single mutants of site 2, the Glu160Lys, Glu160Arg, Glu157Lys (E157K), and Glu157Arg mutants, and an E157K-E330K combination mutant. The last three mutants were nonviable. All mutants replicated viral DNA normally, and all except the last two produced particles containing all three capsid proteins and viral DNA. The defect of the site 1-site 2 E157K-E330K double mutant implies that at least one of the sites is required for particle assembly in vivo. The nonviable E157K particles, about 10% larger in diameter than the wild type, were able to enter cells but did not lead to T-antigen expression. Cell-internalized E157K DNA effectively coimmunoprecipitated with anti-Vp1 antibody, but little of the DNA did so with anti-Vp3 antibody, and none was detected in anti-importin immunoprecipitate. Yet, a substantial amount of Vp3 was present in anti-Vp1 immune complexes, suggesting that internalized E157K particles are ineffective at exposing Vp3. Our data show that E157K mutant infection is blocked at a stage prior to the interaction of the Vp3 nuclear localization signal with importins, consistent with a role for calcium-binding site 2 in postentry steps leading to the nuclear import of the infecting SV40.

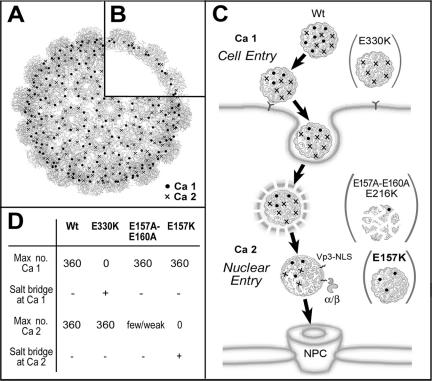

Calcium ions are an integral part of simian virus 40 (SV40) and murine polyomavirus (Py) (2, 5, 17, 30). The major capsid proteins (Vp1) of various polyomaviruses can assemble into virus-like particles in the presence of calcium ions (3, 4, 9, 12, 13, 24, 28, 29). On an SV40 capsid, there are about 700 sites for binding calcium ions (Fig. 1A). These calcium-binding sites, occurring as pairs of site 1 and site 2, are situated at the base of the 72 Vp1 pentamers (Fig. 1B). The twin sites coordinate calcium ions among two Vp1 chains from one pentamer and one carboxy-terminal tail from a second pentamer, thereby reinforcing interpentamer interaction on the capsid (17, 30). Five of the seven acidic residues from the twin sites (Glu48 and Glu330 of site 1, Glu157 and Glu160 of site 2, and Glu216 belonging to both sites) contribute to the formation of infectious SV40 (16). Three of the 21 calcium site mutants analyzed previously can form particles, but their particles cannot initiate infection of the new host (16). The mutants' defects suggest that the two calcium sites mediate different functions in early stages of infection: site 1 mediates cell binding and entry and site 2 mediates the nuclear entry of viral DNA. The characteristics of the three previously described mutants and a mutant described in the present report are summarized as part of the model presented in Fig. 1. The nonviable site 1 E330K mutant particles cannot attach to or enter the cell (16). The substituted Lys330 side chain is predicted to make a salt bridge with another acidic side chain at site 1 (Glu48 or Glu216), thus locking the site from calcium ion coordination. In contrast, the site 2 E157A-E160A and dual-site E216K mutant particles can enter the cell normally but fail to enter the nucleus, apparently as a result of premature particle dissociation in the cytoplasm (16). The two apolar alanine side chains in place of glutamates at site 2 for the E157A-E160A mutant appear to have a destabilizing effect on the cell-internalized particle, as does the lysine substitution of the E216K mutant.

FIG. 1.

Calcium-binding sites: location on capsid and function in early infection events. (A and B) Locations of calcium-binding sites on the SV40 capsid. The capsid is represented as an α-carbon chain trace of component Vp1 molecules (17, 30), onto which the approximate positions of calcium site 1 (Ca 1) and calcium site 2 (Ca 2) are marked. A front view (A) and a cross-sectional view (B) are presented. (C) Proposed functions of calcium-binding sites in SV40 infection. The major events leading to productive infection by a wild-type virion (Wt) in connection with calcium exchanges at site 1 and site 2 are schematically diagramed. For simplicity, only a small, arbitrarily chosen number of all possible sites 1 or sites 2 is illustrated on each particle. This model portrays a scenario in which some of the calcium ions coordinated at the sites are released at specific stages of infection. Cell entry of the virus is achieved through interaction with a cell surface receptor (Y-shaped molecule on the plasma membrane) and internalization into a membrane-enclosed compartment. Nuclear entry of the virus is achieved through escape from a membrane compartment and exposure of the Vp3 NLS (zigzag lines) for interaction with importins α and β (α/β), leading to import through the nuclear pore complex (NPC). The particles of the E330K (illustrated as lacking functional site 1; cell-binding defective), E157A-E160A and E216K (lacking functional site 2; prematurely dissociating), and E157K (lacking functional site 2; Vp3 exposure defective) mutants are placed at the respective blocked stages of infection. (D) Summary of expected calcium-binding site characteristics for wild-type and mutant particles. The number of calcium ions that can be coordinated by all the sites 1 or sites 2 in one capsid is presumed to be 360 (maximum [Max] of 360) if all site 1 or site 2 side chains are intact. The predicted presence (denoted by a +, as opposed to − for the absence) of a salt bridge at site 1 or site 2 for the E330K or E157K mutant, respectively, is expected to eliminate calcium coordination at the respective mutated site (zero calcium ions at site 1 or 2). The E157A-E160A mutant is expected to coordinate few or no calcium ions at its site 2 as a result of weakened affinity of the site for the ion (few/weak).

We reasoned that if Glu157 or Glu160 was replaced with a basic amino acid, the substituted side chain may form a salt bridge with the remaining acidic side chain(s) at site 2 (Glu160 or Glu157, Glu216, and Asp345), analogous to the site 1-locked E330K mutant.

We expect that such site 2-locked mutants are able to assemble particles, but the particles may be defective in reinfection. Here, we provide evidence for the formation of such particles by the site 2 E157K mutant. E157K mutant particles can gain entry into the host cell but are blocked at some postentry process preceding entry into the cell nucleus (Fig. 1C and D). We also show by a simultaneous mutation at both sites, E157K-E330K, that calcium coordination at least at one of the two sites is necessary for particle assembly in vivo.

Calcium site 2 mutagenesis and mutant analysis.

Four site 2 mutants, the lysine-substituted E157K and E160K mutants and the arginine-substituted E157R and E160R mutants, and a double lysine-substituted two-site mutant, the E157K-E330K mutant, were made by inserting the respective mutation-containing XbaI-to-PstI PCR fragment into pBS-Vp1 (15). Each PCR fragment was generated using pBS-Vp1 as a template, 5′-GGAGTAGCTCTAGAATGAAGATG-3′ as the sense primer, and 5′-AACACACCCTGCAGuvwCAAAGGxyzCCCACCAACAGCAAAAAATG-3′ as the antisense primer, where uvw and xyz are CTC and TTT (E157K and E157K-E330K), CTC and ACG (E157R), TTT and TTC (E160K), and ACG and TTC (E160R), respectively. Mutant NO-pSV40 plasmids were then made by insertion into NO-pSV40-BSM (15), the AflII-to-ApaI fragment from the respective mutant pBS-Vp1s. The NO-pSV40-E157K-E330K mutant was made by inserting the E157K mutation into NO-pSV40-E330K (16). Mutant NO-SV40 genomes were prepared from their NO-pSV40 counterparts as described previously (11).

We transfected CV-1 monkey kidney cells with these mutant DNAs and examined at 72 h posttransfection their capability to replicate the viral DNA and produce capsid proteins that localize to the nucleus (16). All mutants replicated viral DNA to extents similar to that of the wild type (Fig. 2A, upper panel). The extent of Vp1 accumulation varied with the mutant, from the wild-type-comparable levels (Fig. 2A, lower panel, lanes 1 and 6) of the E157K and E160R mutants (lanes 2 and 5) to the reduced levels of the E160K and E157K-E330K mutants (lane 4 and 7) and the greatly diminished level of the E157R mutant (lane 3). It is possible that certain Vp1 mutants are more prone to degradation due to structural features of the mutant proteins or as a consequence of unsuccessful particle assembly in the nucleus. A similarly low Vp1 steady-state level has been observed for another site 2 mutant, the E157Q-E160Q-D345N mutant (16). Yet, each mutant Vp1 localized predominantly in the nucleus, along with associated wild-type minor capsid proteins Vp2 and Vp3 (Vp2/3) (Fig. 2B, panels a through n). Next, the ability of the mutants to form particles was assessed. The lysates of cells harvested at 72 h posttransfection were treated with DNase I (which degrades free or assembly intermediate-associated viral DNAs but not encapsidated viral DNAs), sedimented through sucrose gradients, and probed for the distributions of Vp1 and viral DNA in the fractions by Western and Southern blot analyses, respectively (Fig. 2C to G). The viability of the mutants was determined by plaque assays using the transfected cell lysates (Table 1). Based on these assessments, the mutants fall into three phenotypic groups, as discussed below.

FIG. 2.

DNA replication, capsid protein expression, and particle formation by mutants. (A) DNA replication and Vp1 accumulation. (Upper panel) Viral DNA was extracted by the Hirt method (10) from 106 CV-1 cells at 72 h posttransfection (15) with the indicated wild-type or mutant NO-SV40 DNA, digested with KpnI and DpnI, resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis, and stained with ethidium bromide. A single low-molecular-weight species at 5.2 kbp was detected for each sample as shown. (Even though the NO-SV40 DNAs used for transfections were equimolar mixtures with pBR322 DNA derived from the processing of NO-pSV40 precursors [11], no additional fragments corresponding to pBR322 were detectable in the Hirt extracts of transfected cells following KpnI-DpnI or BamHI digestion.) (Lower panel) A 2.5 × 104-cell sample per wild-type or mutant DNA from the same transfection experiment was analyzed by anti-Vp1 Western blotting, as described before (14). (B) Subcellular localization of capsid proteins. Cells grown on coverslips were transfected with each indicated NO-SV40 DNA, cultured for 48 h, fixed, doubly stained with guinea pig anti-Vp1 (a, c, e, g, i, k, and m) or rabbit anti-Vp3 (b, d, f, h, j, L, and n), and then doubly stained with rhodamine-labeled (a, c, e, g, i, k, and m) or fluorescein-labeled (b, d, f, h, j, L, and n) secondary antibodies as described before (14). The same cells are shown in panels a and b, c and d, e and f, g and h, i and j, k and L, and m and n. (C to G) Particle formation. Lysates were prepared from cells at 72 h posttransfection (15) with wild-type (C), E157K (D), E157R (E), E160K (F), or E157K-E330K (G) NO-SV40 DNA, treated with DNase I, and sedimented through a 5 to 32% sucrose gradient, as described previously (15). The total number of transfected cells used for the analysis is indicated below each mutant name. Of the 17 fractions collected from the bottom of the gradient, 2/3 was analyzed for viral DNA by Southern blotting (15), and 1/40 was analyzed for Vp1 by Western blotting. The profile for the NO-SV40-E160R mutant was highly similar to that of the E160K mutant shown in panel F. The arrowhead indicates the peak position of viral DNA and Vp1 presence for the wild-type sample in panel C. Short lines point to the species of viral DNA visible in each sample.

TABLE 1.

Viability of calcium-binding site 2 mutants

| NO-SV40 DNA | Titer (PFU)a | Plaque diam (mm)d |

|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 1.1 × 108 | 6.4 ± 1.2 |

| E160K mutant | 6.2 × 106 | 5.2 ± 0.2 |

| E160R mutant | 2.0 × 106 | 4.1 ± 0.3 |

| E157K mutant | 0b | |

| E157R mutant | 0b | |

| E157K-E330K mutant | NDc |

PFU of cell lysates from one 60-mm dish that was transfected with the indicated viral DNA. Values represent averages from two experiments.

No plaques detected in one-eighth of the lysates harvested from one transfected 60-mm dish.

ND, not done.

Values represent means ± standard deviations.

Group 1: assembly-competent and viable E160K and E160R mutants.

The sucrose gradient profiles of the E160K and E160R mutants (Fig. 2F) were similar to that of the wild-type sample (Fig. 2C), with a peak distribution of viral DNA and Vp1 around fractions 4 through 6, suggesting the formation of particles that enclosed viral DNAs and protected them from nuclease digestion (Fig. 2F). Fewer particles were made by the mutants (especially the E160K mutant) than by the wild type, as evidenced by the increased amounts of mutant-transfected materials needed for the detections (Fig. 2F compared with 2C). The mutant particles from peak sucrose fractions exhibited a normal capsid protein composition, with proportions of Vp1, Vp2, and Vp3 similar to those of the wild-type particles (Fig. 3A, lanes 3 and 4 compared with lane 1). The viability of the mutants was somewhat reduced (17- to 55-fold) compared to that of the wild type (Table 1), as was that of the previously reported E160A mutant (16). Glu160 is less conserved than Glu157 in the polyomavirus family and, as the above data indicate, is not essential for assembly or viability when Glu157 is intact. A basic side chain at residue 160 may preserve particle formation and infectivity either by forging a stabilizing salt bridge with the remaining site 2 acidic side chains, thereby eliminating calcium coordination at site 2, or by not being involved in any interactions that would disrupt the coordination. We favor the latter interpretation because of the phenotypes of the Glu157 mutants described below.

FIG. 3.

Capsid composition, EM, and infection processes of mutant particles. (A) Capsid protein composition. Peak sucrose fractions for wild-type and various mutant particles, prepared similarly to those for Fig. 2C through G, were pooled and probed for the composition of capsid proteins by anti-Vp1 (upper panel) or anti-Vp3 (lower panel) Western blot analysis. Bands corresponding to Vp1, Vp2, and Vp3 are marked. (B) Electron micrograph of E157K particles. E157K mutant particles (a) or wild-type SV40 virions (b) were purified as for panel A from 4 × 108 to 10 × 108 viral DNA-transfected cells and further purified through a second round of sucrose sedimentation. Three microliters of the E157K mutant or wild-type particles, containing about 1.6 × 107 or 6.6 × 107 particles per μl, respectively, was applied to a glow-discharged carbon-coated copper grid and allowed to settle for 20 s. The excess solution was removed by blotting with a filter paper, and the grid was washed once with 3 μl of water and then stained with a drop of 2% uranyl acetate solution for 15 s. The excess staining was removed by blotting, and the grid was air dried. Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) was included with the sample as a calibration standard. (The TMV-containing images were windowed in 1,024- by 1,024-pixel images, from which the power spectrum of the images was calculated to reveal the 23-Å layer lines. The half-distance between two layer lines was measured in pixels and used to estimate the pixel size.) The specimens were observed with a JEOL 1230 electron microscope. The mean diameter of the SV40 virions is 47.5 ± 1.9 nm (n = 233), and that of the E157K particles is 52.0 ± 4.0 nm (n = 250). Bar, 20 nm. (C) Cell attachment and internalization by E157K particles. Similar to the previously described procedure (16, 21), cells grown in 100-mm dishes were infected for 6 h, at 1,000 particles per cell, with peak sucrose fractions containing wild-type or E157K particles. One set of infected cells was harvested by scraping (Cell assoc), and another set was harvested by trypsin treatment (Internalized). Viral DNA was extracted by the Hirt method (10) from 2 × 106 of each type of infected cells, linearized by BamHI digestion, resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis, and detected by ethidium bromide staining. (D) Association of internalized E157K DNA with capsid proteins and importins. The state of the internalized E157K mutant particles was assessed by immunoprecipitation essentially as described before (16, 21). Briefly, the cytoplasmic fraction was prepared from cells at 6 h postinfection with wild-type particles (upper panel) or E157K mutant particles (lower panel). Aliquots of the cytoplasmic fractions, equivalent to 2 × 106 infected cells, were reacted with anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) (lane 2, Cont), anti-Vp1 (lane 3, Vp1), affinity-purified anti-Vp3 (lane 4, Vp3), or a mixture of anti-importin-α and anti-importin-β antibodies (lane 5, Imps). The coimmunoprecipitated (IP) viral DNA was purified from the immune complexes in the presence of 20 to 50 pg of the NO-pSV40Δ NcoI control DNA and detected via semiquantitative PCR. The expected amplification of product of the NO-SV40 genome is 2.2 kbp (arrow, Viral DNA), whereas that of the control DNA is 1.7 kbp (arrowhead, Cont. DNA). For comparison, the viral DNA content of the input cytoplasmic lysate, equivalent to 4 × 105 infected cells (lane 1), was similarly purified in the presence of the control DNA and detected by PCR. (E) Association of Vp3 with Vp1 following E157K particle internalization. The cytoplasmic fraction was extracted from 1 × 108 wild-type (Wt, lanes 1 and 2) or 2 × 108 E157K mutant (lane 3) particle-infected cells at 6 h postinfection and reacted with anti-β-galactosidase (Anti-β-Gal) or anti-Vp1 antibody. The immune complexes were collected via reaction with TrueBlot anti-rabbit Ig beads from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Both the immunoprecipitates (upper panel) and the supernatants remaining after the bead reactions (lower panel) were probed by anti-Vp1 and anti-Vp3 Western blot analyses similar to those described before (14), except affinity-purified anti-Vp3 IgG was used as the primary antibody for the latter blot analysis and TrueBlot horseradish peroxidase anti-rabbit IgG from eBioscience was used as the secondary antibody for both blot analyses. Purified SV40 virions were included in lane 4 as a Western blot analysis control. Bands corresponding to Vp1 and Vp3 are marked.

Group 2: assembly-defective and nonviable E157R and E157K-E330K mutants.

The sucrose gradient profile of the E157R mutant showed little detectable viral DNA or Vp1, even though 10 times the mutant-transfected lysates were sedimented (Fig. 2E), indicating that particle formation is disrupted. This severe block in particle formation is consistent with the loss of viability (Table 1). The phenotype of the E157R mutant is much more severe than those of the viable E160K/R (Table 1) and D345K/R (16) mutants and resembles that of the assembly-defective, poorly viable both-site E216R mutant (16). That a bulky, positively charged side chain is not tolerated at residue 157 but is tolerated at site 2 residues 160 and 345 implies that the accurate positioning of the Glu157 side chain is especially critical for the structure and function of site 2.

For the E157K-E330K mutant, the similarly scaled-up lysate material revealed broadly distributed mutant Vp1 in the sucrose gradient and very little viral DNA (Fig. 2G). This profile reflects the formation of heterogeneous capsid protein complexes or assembly intermediates that fail to package the viral DNA into DNase I-resistant particles. The E157K-E330K mutant is nonviable, as are its parental single mutants, the E330K mutant of site 1 (16) and the E157K mutant of site 2 (Table 1; also see below). The assembly defect of the double mutant suggests that at least one intact calcium-binding site, either site 1 or site 2, is necessary to support efficient particle formation in the nucleus of the host cell. It appears that calcium ion coordination, but not rigid replacement salt bridges, provides a flexibility needed for the interactions between the core regions of Vp1 pentamers and the invading C-terminal arms of adjacent pentamers, hence facilitating SV40 assembly. Yet, it remains possible that alternative mutation combinations involving both of the calcium-binding sites, rather than the E157K-E330K combination, would supply surrogate bonds to calcium coordination and permit the formation of calciumless particles.

Two distinct cell-free pathways for the assembly of virus-like particles from Vp1 pentamers have been described: one is calcium dependent (2-5, 9, 12, 13, 24, 28, 29) and the other calcium independent and chaperone and cochaperone dependent (6). That is, capsid formation can take place under certain ionic or buffer conditions or in the presence of assisting proteins, without calcium ions. These findings do not rule out an essential role for the calcium-binding sites in the intracellular assembly of infectious SV40, and it is quite possible that both calcium ions and chaperone proteins work together in the host cell nucleus to bring about the efficient assembly of the infectious particles.

Group 3: assembly-competent but nonviable E157K mutant.

The particles formed by the E157K mutant and the wild-type virus and E160K and E160R mutants were similar in capsid protein composition (Fig. 3A, lane 2). Although both the viral DNA and Vp1 of E157K particles sedimented in regions in the sucrose gradient similar to those of wild-type particles, their distribution was broader than that of their wild-type counterpart (Fig. 2D). This difference may suggest the presence of heterogeneous assembly intermediates in mutant-transfected cells. To examine the E157K particles by electron microscopy (EM), the sucrose gradient preparation of mutant-transfected material was scaled up multifold, and the peak particle fractions 4 through 6, which paralleled the profile in Fig. 2D, were pooled, pelleted by sedimentation through a 20% sucrose cushion, and subjected to a second round of sucrose gradient sedimentation. Wild-type particles were prepared in the same manner. Particles in the resulting peak fractions were collected and were examined by EM (22).

Although the spherical shape of the E157K particle is similar to that of the wild-type virion, the diameter (mean ± standard deviation) of the mutant particles is 52.0 ± 4.0 nm (Fig. 3B, panel a), which is on average about 10% larger compared with that of wild-type particles, 47.5 ± 1.9 nm (Fig. 3B, panel b). The larger capsid size standard deviation for the mutant particles correlates with their greater heterogeneity of sedimentation position in the sucrose gradient (Fig. 2D) compared with that of wild-type particles. The molecular basis for the expansion and larger size distribution of E157K mutant particles is not known at present. Further structural analysis of the E157K particles could illuminate the molecular basis of expansion. E157K particles are noninfectious (Table 1), indicating that some essential function of the mutant particles is amiss.

Nuclear entry defect of E157K mutant particles.

E157K mutant particles prepared as pooled peak sucrose fractions as described above were used to infect new cells, and the ability of the particles to enter the cell and the nucleus was assessed. Trypsin treatment of the infected cells or the lack of treatment prior to harvesting was used to distinguish particles that had entered cells from particles that had attached to but had not necessarily entered the cells (16, 21). E157K particles (Fig. 3C, lanes 3 and 4) bound and entered cells as effectively as wild-type particles (lanes 1 and 2), judged from the strengths of the viral DNA signals for the trypsin-treated (lanes 2 and 4) and untreated (lanes 1 and 3) infected cells. The mutant particles did not lead to any detectable T-antigen expression 20 h following infection. In comparison, 59% of the cells infected with wild-type particles expressed nuclear T antigen at that time point. The mutant is blocked, therefore, somewhere between cell entry and nuclear entry.

The E157K particles contain wild-type minor capsid proteins, which must be exposed in the cytoplasm to allow for interaction with the importins, or cellular receptors for nuclear entry (21). We tested whether the internalized E157K particle could expose the interior Vp2/3 and be recognized by the importins. At 6 h postinfection, a cytoplasmic extract containing the internalized particles was prepared and reacted with antibodies against Vp1 and Vp3 (and Vp2) or importins α and β. The viral DNA in the resulting immune complexes (IPs) was quantitated by PCR, as described previously (16, 21). We found that much internalized E157K DNA was in the Vp1 IPs, similar to the amount found for internalized wild-type DNA, suggesting that the viral DNA was in association with the mutant Vp1 (Fig. 3D, lane 3, lower panel compared with upper panel). Very little mutant DNA was detected in Vp3 IPs compared with the wild-type DNA (lane 4, lower panel versus upper panel). No E157K DNA was detected in importin IPs, unlike the strong association with the wild-type DNA (Fig. 3D, lane 5, lower panel versus upper panel).

There are two possible interpretations for the observed result: either the minor capsid proteins dissociated from the mutant capsids upon cell entry and were thus no longer in complex with the rest of the particles or Vp2/3 was still part of the particles but remained hidden inside them. To investigate these possibilities, the Vp1 IPs, prepared as for Fig. 3D, were probed for Vp3 as well as for Vp1 by Western blot analysis. We found that both Vp1 and Vp3 were present in the anti-Vp1 IPs for the E157K mutant as well as the wild-type sample (Fig. 3E, upper panel, lanes 3 and 2, respectively). Relatively little of either capsid protein remained in the supernatant following anti-Vp1 immunoprecipitation for both the mutant and the wild type (Fig. 3E, lower panel, lanes 3 and 2, respectively), whereas the majority of capsid proteins were still found in the supernatant of the anti-β-galactosidase control reaction of the wild-type sample (lane 1). Although anti-Vp3 antibody reacts with Vp2, Vp2 was not detectable in the input cytoplasmic extract or in the anti-Vp1 immunoprecipitate because of the low abundance of this minor capsid protein. Therefore, most of Vp3, and possibly Vp2, remained in complex with the E157K mutant or wild-type Vp1 following the internalization of the respective particles. Since the nuclear localization signal (NLS) of Vp2/3 serves as the NLS of the virion (21), the poor exposure of these signals from E157K particles would understandably compromise the recognition of the mutant particles by the importin receptors and prevent the effective nuclear entry of the infecting E157K DNA. This lack of importin recognition explains the lack of infectivity of E157K particles.

The phenotypes of the E330K (16) and E157K mutants are consistent with the model portrayed in Fig. 1, in which calcium ions are released or acquired at some of the calcium-binding sites in response to specific environmental cues, leading to a conformational change in the capsid. In this model, a conformational alteration mediated by site 1 calcium exchanges (a function the site 1-locked E330K particle presumably has lost) helps to expose structural determinants or signals for cell adsorption, enabling cell entry. A subsequent structural alteration mediated by site 2 calcium exchanges (a function the site 2-locked E157K particle presumably has lost) helps to expose the minor capsid proteins and their NLSs on the capsid surface, permitting nuclear entry. In both cases, calcium coordination is expected to impart the infecting particle with the structural flexibility to expose specific capsid protein determinants, which would then allow the virus to interact with the appropriate cellular components. Further biochemical and structural studies are needed to substantiate this model.

Evidence suggests that the infection pathways of SV40 (1, 23, 26), Py (19, 27), and BK virus (7, 8) involve the caveolae and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) lumen. SV40 and Py particles are believed to escape ER enclosure and become released into the cytosol prior to being imported into the nucleus (23, 25). This ER penetration step has been speculated to involve a conformational change of Py Vp1 (18). A protein disulfide isomerase-like, ER-resident chaperone, ERp29, was recently reported to induce structural alteration in Py particles and appears to be critical for Py infection (18). The presence of ERp29 causes the C-terminal arms of Vp1 to become exposed from Py capsids and allows them to embed in liposomes (18). We have postulated that following cell entry, a conformational change of the capsid that exposes the Vp2/3 NLS and the interaction of this NLS with importins in the cytosol are necessary for the nuclear entry of SV40 (21). This conformational alteration, which converts SV40 into a nuclear entry-competent state, maintains the Vp1/Vp3 mass ratio of a virion (20). By affecting the potential of the virus to undergo the critical postentry structural change, the E157K mutation may hamper the accessibility of the Vp3 NLS or may alter the intracellular trafficking of the virus, leading to blocked nuclear entry of the viral DNA. It remains unclear what might trigger the conformational change in the internalized SV40 capsid or where in the cell it takes place. Further studies with the E157K mutant may elucidate the subcellular compartment and the trigger molecules that induce the architectural change in the infecting SV40 necessary for its nuclear entry.

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert C. Liddington and Akira Nakanishi for helpful discussions. We also thank Akira Nakanishi for assistance with the DNA immunoprecipitation experiment.

This work was supported by grant R01 CA-50574 to H.K. from the National Cancer Institute. The EM work was supported by grants to R.H.C. from EU Framework 6 and from the University of California Cancer Research Coordinating Committee. S.A. received a scholarship from the Medical Scholars Program at Mahidol University, Thailand.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 14 March 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson, H. A., Y. Chen, and L. C. Norkin. 1996. Bound simian virus 40 translocates to caveolin-enriched membrane domains, and its entry is inhibited by drugs that selectively disrupt caveolae. Mol. Biol. Cell 7:1825-1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brady, J. N., V. D. Winston, and R. A. Consigli. 1977. Dissociation of polyoma virus by the chelation of calcium ions found associated with purified virions. J. Virol. 23:717-724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang, D., C. Y. Fung, W. C. Ou, P. C. Chao, S. Y. Li, M. Wang, Y. L. Huang, T. Y. Tzeng, and R. T. Tsai. 1997. Self-assembly of the JC virus major capsid protein, VP1, expressed in insect cells. J. Gen. Virol. 78:1435-1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, P. L., M. Wang, W. C. Ou, C. K. Lii, L. S. Chen, and D. Chang. 2001. Disulfide bonds stabilize JC virus capsid-like structure by protecting calcium ions from chelation. FEBS Lett. 500:109-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christiansen, G., T. Landers, J. Griffith, and P. Berg. 1977. Characterization of components released by alkali disruption of simian virus 40. J. Virol. 21:1079-1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chromy, L. R., J. M. Pipas, and R. L. Garcea. 2003. Chaperone-mediated in vitro assembly of polyomavirus capsids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:10477-10482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drachenberg, C. B., J. C. Papadimitriou, R. Wali, C. L. Cubitt, and E. Ramos. 2003. BK polyoma virus allograft nephropathy: ultrastructural features from viral cell entry to lysis. Am. J. Transplant. 3:1383-1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eash, S., W. Querbes, and W. J. Atwood. 2004. Infection of Vero cells by BK virus is dependent on caveolae. J. Virol. 78:11583-11590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haynes, J. I., II, D. Chang, and R. A. Consigli. 1993. Mutations in the putative calcium-binding domain of polyomavirus VP1 affect capsid assembly. J. Virol. 67:2486-2495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirt, B. 1967. Selective extraction of polyoma DNA from infected mouse cell cultures. J. Mol. Biol. 26:365-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishii, N., A. Nakanishi, M. Yamada, M. H. Macalalad, and H. Kasamatsu. 1994. Functional complementation of nuclear targeting-defective mutants of simian virus 40 structural proteins. J. Virol. 68:8209-8216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishizu, K. I., H. Watanabe, S. I. Han, S. N. Kanesashi, M. Hoque, H. Yajima, K. Kataoka, and H. Handa. 2001. Roles of disulfide linkage and calcium ion-mediated interactions in assembly and disassembly of virus-like particles composed of simian virus 40 VP1 capsid protein. J. Virol. 75:61-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanesashi, S. N., K. Ishizu, M. A. Kawano, S. I. Han, S. Tomita, H. Watanabe, K. Kataoka, and H. Handa. 2003. Simian virus 40 VP1 capsid protein forms polymorphic assemblies in vitro. J. Gen. Virol. 84:1899-1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li, P. P., A. Nakanishi, D. Shum, P. C.-K. Sun, A. M. Salazar, C. F. Fernandez, S.-W. Chan, and H. Kasamatsu. 2001. Simian virus 40 Vp1 DNA-binding domain is functionally separable from the overlapping nuclear localization signal and is required for effective virion formation and full viability. J. Virol. 75:7321-7329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li, P. P., A. Nakanishi, M. A. Tran, A. M. Salazar, R. C. Liddington, and H. Kasamatsu. 2000. Role of simian virus 40 Vp1 cysteines in virion infectivity. J. Virol. 74:11388-11393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li, P. P., A. Naknanishi, M. A. Tran, K. Ishizu, M. Kawano, M. Phillips, H. Handa, R. C. Liddington, and H. Kasamatsu. 2003. Importance of Vp1 calcium-binding residues in assembly, cell entry, and nuclear entry of simian virus 40. J. Virol. 77:7527-7538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liddington, R. C., Y. Yan, J. Moulai, R. Sahli, T. L. Benjamin, and S. C. Harrison. 1991. Structure of simian virus 40 at 3.8-Å resolution. Nature 354:278-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magnuson, B., E. K. Rainey, T. Benjamin, M. Baryshev, S. Mkrtchian, and B. Tsai. 2005. ERp29 triggers a conformational change in polyomavirus to stimulate membrane binding. Mol. Cell 20:289-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mannová, P., and J. Forstova. 2003. Mouse polyomavirus utilizes recycling endosomes for a traffic pathway independent of COPI vesicle transport. J. Virol. 77:1672-1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakanishi, A., P. P. Li, Q. Qu, Q. H. Jafri, and H. Kasamatsu. 2007. Molecular dissection of nuclear entry-competent SV40 during infection. Virus Res. 124:226-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakanishi, A., D. Shum, H. Morioka, E. Otsuka, and H. Kasamatsu. 2002. Interaction of the Vp3 nuclear localization signal with the importin α2/β heterodimer directs nuclear entry of infecting simian virus 40. J. Virol. 76:9368-9377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nilsson, J., N. Miyazaki, L. Xing, B. Wu, L. Hammar, T. C. Li, N. Takeda, T. Miyamura, and R. H. Cheng. 2005. Structure and assembly of a T=1 virus-like particle in BK polyomavirus. J. Virol. 79:5337-5345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Norkin, L. C., H. A. Anderson, S. A. Wolfrom, and A. Oppenheim. 2002. Caveolar endocytosis of simian virus 40 is followed by brefeldin A-sensitive transport to the endoplasmic reticulum, where the virus disassembles. J. Virol. 76:5156-5166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ou, W. C., L. H. Chen, M. Wang, T. H. Hseu, and D. Chang. 2001. Analysis of minimal sequences on JC virus VP1 required for capsid assembly. J. Neurovirol. 7:298-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pelkmans, L., and A. Helenius. 2003. Insider information: what viruses tell us about endocytosis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 15:414-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pelkmans, L., J. Kartenbeck, and A. Helenius. 2001. Caveolar endocytosis of simian virus 40 reveals a new two-step vesicular-transport pathway to the ER. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:473-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richterová, Z., D. Liebl, M. Horak, Z. Palkova, J. Stokrova, P. Hozak, J. Korb, and J. Forstova. 2001. Caveolae are involved in the trafficking of mouse polyomavirus virions and artificial VP1 pseudocapsids toward cell nuclei. J. Virol. 75:10880-10891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodgers, R. E. D., D. Chang, X. Cai, and R. A. Consigli. 1994. Purification of recombinant budgerigar fledgling disease virus VP1 capsid protein and its ability for in vitro capsid assembly. J. Virol. 68:3386-3390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salunke, D. M., D. L. Caspar, and R. L. Garcea. 1986. Self-assembly of purified polyomavirus capsid protein VP1. Cell 46:895-904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stehle, T., S. J. Gamblin, Y. Yan, and S. C. Harrison. 1996. The structure of simian virus 40 refined at 3.1 Å resolution. Structure 4:165-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]