Abstract

Clathrin-mediated endocytosis is a common pathway for viral entry, but little is known about the direct association of viral protein with clathrin in the cytoplasm. In this study, a putative clathrin box known to be conserved in clathrin adaptors was identified at the C terminus of the large hepatitis delta antigen (HDAg-L). Similar to clathrin adaptors, HDAg-L directly interacted with the N terminus of the clathrin heavy chain through the clathrin box. HDAg-L is a nucleocytoplasmic shuttle protein important for the assembly of hepatitis delta virus (HDV). Here, we demonstrated that brefeldin A and wortmannin, inhibitors of clathrin-mediated exocytosis and endosomal trafficking, respectively, specifically blocked HDV assembly but had no effect on the assembly of the small surface antigen of hepatitis B virus. In addition, cytoplasm-localized HDAg-L inhibited the clathrin-mediated endocytosis of transferrin and the degradation of epidermal growth factor receptor. These results indicate that HDAg-L is a new clathrin adaptor-like protein, and it may be involved in the maturation and pathogenesis of HDV coinfection or superinfection with hepatitis B virus through interaction with clathrin.

Hepatitis delta virus (HDV) causes fulminant hepatitis and progressive chronic liver cirrhosis in patients superinfected or coinfected with hepatitis B virus (HBV) (1, 38). HDV particles are enveloped by the HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) (22), but replication of the viral genome is independent of the helper HBV (21). The HDV genome is a single-stranded circular RNA molecule of approximately 1.7 kilobases that encodes the only known HDV protein, hepatitis delta antigen (HDAg). Two forms of HDAg, small HDAg (HDAg-S) and large HDAg (HDAg-L), which contain 195 (24 kDa) and 214 (27 kDa) amino acid residues, respectively, were detected in the livers and sera of HDV-infected patients (5, 49). The HDAgs are translated from the same initiation codon of a single open reading frame (25) and share identical functional domains except for an additional 19-amino-acid motif at the C terminus of the HDAg-L resulting from RNA editing (33, 34).

HDAg-S is essential for the replication of HDV RNA (21), whereas HDAg-L is required for HDV assembly in a later stage of viral multiplication (4, 8). The unique C-terminal domain of HDAg-L bears an isoprenylation motif (211-CRPQ-214). Isoprenylation and proline-rich motifs at the unique C terminus are important for the interaction of HDAg-L with HBsAg and the assembly of HDV (8, 9, 17, 20). Both HDAg-S and HDAg-L possess nuclear localization signals (NLSs) spanning amino acid residues 35 to 88 and are mainly localized to the nucleus in the absence of HBsAg (6, 7). Nevertheless, in the presence of small HBsAg, HDAg-L localizes to both the nucleus and the cytoplasm. A nuclear export signal (NES) at the unique C terminus of HDAg-L was identified (24). Recently, we also identified a cellular protein, NESI, which specifically interacts with the NES of HDAg-L and is essential for HDAg-L-mediated nuclear export of HDV RNA (47). Nevertheless, how and where cytoplasmic HDAg-L and HBsAg form HDV particles and exit are not clear.

HDV has been identified in certain HBV carriers for 30 years (39). However, the mechanisms by which HDV infection contributes to clinical hepatitis are poorly understood. A number of studies have been carried out to examine the potential impact of HDAg expression on the phenotypes of cells, but the results were controversial. One suggested that overexpression of HDAg-S in the absence of HDV RNA replication has a direct cytotoxic effect that leads to apoptosis in a stably transfected cell line (26). Another detected cell cycle arrest in insect cells that have been infected with HDAg-S recombinant baculovirus (18). Nevertheless, transgenic mice expressing HDAg-S or HDAg-L alone showed little cellular injury (14, 32). Several studies have indicated the possible role of nucleus-localized HDAg-L as a cotransactivator (11, 12, 48), but few reports, on the other hand, studied the effects of cytoplasm-localized HDAg-L on host cells.

In this study, we intend to examine possible interactions between cytoplasm-localized HDAg-L and host factors and to elucidate possible mechanisms of HDAg-L involvement in the viral life cycle and the pathogenesis of HDV infection at the molecular level. The results demonstrated that HDAg-L directly interacted in vitro with the N-terminal domain of the clathrin heavy chain (CHC) through its putative clathrin box at the C terminus. The interaction of HDAg-L with CHC in the trans-Golgi network (TGN) facilitated the maturation of HDV-like particles (hepatitis delta VLPs) in cultured cells. In addition, cytoplasmic HDAg-L colocalized with CHC and induced an effective block on clathrin-mediated protein endocytosis and membrane trafficking. Previously, cirrhosis development without nodular regeneration was observed in HDV-infected hepatocytes (40). Our finding regarding the inhibitory effects of HDAg-L on clathrin-mediated protein transport provides one of the possible mechanisms by which HDV is responsible for the growth defects of hepatocytes and for progressive chronic liver disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids. (i) pGEX-HDAg-L(198-210), pGEX-HDAg-L(198-210)-L199A, and pGEX-HDAg-L(198-210)-D203A.

For construction of plasmid pGEX-HDAg-L(198-210), a cDNA fragment encompassing HDAg-L from amino acid residues 198 to 210 was generated by annealing two synthetic oligonucleotides representing the two strands of HDAg-L(198-210) with additional recognition sequences of EcoRI/SalI at the ends. The cDNA fragment was subsequently cloned into the EcoRI/SalI sites of plasmid pGEX-6P-1 (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences). Similar approaches were taken with synthetic oligonucleotides in which Leu-199 and Asp-203 have been mutated to Ala to generate mutant plasmids pGEX-HDAg-L(198-210)-L199A and pGEX-HDAg-L(198-210)-D203A, respectively.

(ii) pCMV-Tag2C-HDAgL, pCMV-Tag2C-HDAgS, pCMV-Tag2C-HDAgL-d35/88, and pCMV-Tag2C-HDAgS-d35/88.

Construction of plasmids pCMV-Tag2C-HDAgL and pCMV-Tag2C-HDAgS has been described previously (47). For generation of plasmid pCMV-Tag2C-HDAgL-d35/88, a cDNA fragment that represents HDAg-L with an internal deletion from amino acid residues 35 to 88 (HDAg-L-d35/88) was obtained from plasmid pECEL-d35/88 (8) and cloned into plasmid pCMV-Tag2C (Stratagene). Plasmid pCMV-Tag2C-HDAgS-d35/88 was derived from pCMV-Tag2C-HDAgS by replacing the 0.5-kb SmaI fragment containing the N-terminal domain of HDAg-S with the 0.35-kb SmaI fragment derived from pCMV-Tag2C-HDAgL-d35/88.

(iii) pET15b-CHC1-107.

For construction of plasmid pET15b-CHC1-107, a cDNA fragment representing the N-terminal 107 amino acid residues of CHC with NdeI/BamHI recognition sequences at the ends was generated by reverse transcription-PCR from total RNA of HepG2 cells and cloned into the NdeI/BamHI sites of plasmid pET-15b (Novagen). All the expression constructs described above have been verified by DNA sequencing.

Cell lines and DNA transfection.

HepG2 and COS7 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. COS7-L1 and COS7-S8 are stable cell lines that constitutively express HDAg-L and HDAg-S, respectively. The stable cell lines were maintained in culture medium containing 200 μg G418/ml. DNA transfection was performed with cationic liposomes (Invitrogen) followed the procedures as described by the manufacturer.

Antibodies and fluorescence-conjugated reagents.

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies specific to HDAgs were generated as described previously (6) and further purified over a protein G affinity column (Pierce). Goat polyclonal antibodies specific to HBsAg were from Dako. Mouse monoclonal antibodies against CHC and the glutathione S-transferase (GST) epitope were purchased from Transduction Laboratories and Sigma, respectively. Mouse monoclonal antibodies specific to the His epitope were from BD Biosciences Clontech. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against Golgin-245 were generously provided by Fang-Jen Lee (National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan). Mouse monoclonal antibodies to calnexin were from Affinity BioReagents. Alexa 594-conjugated cholera toxin (CTx) subunit B, Alexa 594-conjugated transferrin, Alexa 555-conjugated epidermal growth factor (EGF), and mouse monoclonal antibody specific to the transferrin receptor (TfR) were from Molecular Probes. Anti-EGF receptor (anti-EGFR) antibody was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Horseradish peroxidase-, fluorescein isothiocyanate-, and Cy3-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.

Protein purification from cultured cells and sucrose gradient fractionation.

Total protein lysates were prepared from cultured cells following a lysis in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitor cocktail (1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin A, 1 μg/ml leupeptin). For fractionation, the cleared cell lysates were subjected to a 10% to 40% sucrose gradient centrifugation in PBS at 38,000 rpm for 18 h at 4°C in an SW41 Ti rotor (Beckman). Aliquots of fractions were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and examined by Western blot analysis.

Expression and purification of recombinant fusion proteins and GST pull-down assay.

Expression of GST- and His-tagged fusion proteins in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) was induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside. Following the induction, the bacterial cells were subjected to lysis by sonication in PBS supplemented with 1% Triton X-100 and separated into soluble and insoluble fractions by centrifugation. For further purification of the His-CHC1-107 protein, bacterial lysates loaded on a nickel-agarose column were eluted with solubilization buffer (100 mM Na3PO4, 10 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 0.5% Triton X-100) containing 500 mM imidazole. Following a dialysis against PBS, the purity of the His-CHC1-107 protein reached 95% (data not shown).

To perform a GST pull-down assay with glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences), bacterial lysates containing GST fusion proteins were coupled to the beads and incubated at 4°C overnight with the purified His-CHC1-107 protein or with cellular proteins prepared from HepG2 or COS7 cells. The protein-bound glutathione beads were washed with PBS containing 1% Triton X-100 and examined by Western blot analysis.

Immunofluorescence staining, coimmunoprecipitation, and Western blot analysis.

Immunofluorescence staining (23), coimmunoprecipitation (23), and Western blot analysis (24) were performed as previously described.

Harvest of VLPs and determination of package activity.

To determine the package activities of HDAg-L and HBsAg, HDV- and HBV-like particles were collected from culture media 4 days posttransfection, and the procedures were followed as described previously (24).

Transferrin internalization assay.

Forty-eight hours posttransfection, COS7 cells were starved in OPTI-MEM I (Invitrogen) for 20 min at 37°C. Alexa 594-conjugated transferrin at a concentration of 50 μg/ml was added to the cells and incubated for additional 20 min at 37°C, followed by immunofluorescence staining. The intensities of the Alexa 594-conjugated transferrin images from 10 transfected cells were quantitated without changing the intensity setting for the laser and photomultiplier. The mean intensity of the signal from each cell was quantified with the software provided with the ImageMaster TotalLab version 1.00 analyzer (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences).

EGFR degradation assay.

Forty-eight hours posttransfection, COS7 cells were starved in OPTI-MEM I for 20 min at 37°C. Alexa 555-conjugated EGF at a concentration of 200 ng/ml was added to the cells and incubated for 20 min at 37°C. The cells were then washed with PBS and incubated in DMEM containing cycloheximide (10 μg/ml) for 5 h or otherwise as indicated. Coimmunoprecipitation-Western blot analysis and immunofluorescence staining were performed to detect the expression of HDAgs and the degradation of internalized Alexa 555-conjugated EGF and EGFR. The intensities of the Alexa 555-conjugated EGF images from transfected cells were quantitated as described above for the quantitation of Alexa 594-conjugated transferrin images in the transferrin internalization assay.

RESULTS

Identification of CHC as an HDAg-L-interacting protein.

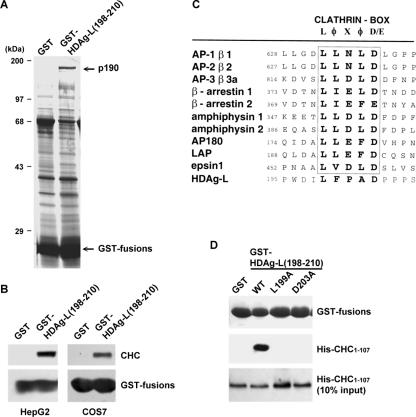

To identify the potential host proteins that have specific interactions with cytoplasm-localized HDAg-L, a GST pull-down assay was performed using a GST fusion protein encompassing the C-terminal domain of HDAg-L from amino acid residues 198 to 210 [GST-HDAg-L(198-210)] and protein lysates of human HepG2 cells. As shown in Fig. 1A, a protein with a molecular mass of 190 kDa (provisionally designated p190) was found to interact with GST-HDAg-L(198-210) but not with the GST control protein. The p190 protein was subjected to trypsin digestion and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis. Spectra representing 11 independent tryptic fragments of 6 to 27 amino acid residues all identified the protein as CHC (data not shown). To further confirm the identity of the HDAg-L-interacting protein and the specificity of the protein interaction, monoclonal antibody specific to CHC was used to perform Western blot analysis following the GST pull-down reaction. The results clearly demonstrated a specific association between GST-HDAg-L(198-210) and endogenous CHC of mammalian cells (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Identification of CHC as an HDAg-L-interacting protein. (A) GST pull-down assay. A GST pull-down assay was performed with HepG2 cell extract and GST-HDAg-L(198-210) or GST control protein as indicated. Silver staining is shown. Arrows indicate the protein bands of p190 and GST fusions for GST and GST-HDAg-L(198-210). Molecular mass markers are denoted on the left. (B) Western blot analysis. GST-HDAg-L(198-210) and GST control protein bound to glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads were incubated independently with the cell lysates prepared from HepG2 and COS7 cells. Following the GST pull-down reaction, Western blot analysis was performed with antibodies specific to CHC and GST as indicated. (C) Sequence alignment of HDAg-L and CHC adaptor proteins. Sequences surrounding the clathrin box in proteins known to interact with clathrin (adapted from the Annual Review of Biochemistry [19] with permission of the publisher) were compared with that for genotype I HDAg-L. Numbers denote the positions of amino acid residues in each protein. The conserved sequences of the clathrin box are shown. (D) Mutational analysis of the clathrin box of HDAg-L. A GST pull-down assay was performed with purified His-CHC1-107 and GST fusions. Proteins present in the affinity-captured complex were detected by Western blot analysis with antibodies against GST and His-tag as indicated. WT, wild type.

Clathrin is known to play direct roles in the genesis and trafficking of transport vesicles at membranes with distinctive vesicle proteins (28). Clathrin-binding proteins, such as the adaptor proteins β-arrestins and amphiphysins, were identified to bind directly to CHC through the conserved clathrin box (LφXφD/E) that consists of polar amino acid residues flanked by hydrophobic and acidic amino acid residues (19). Sequence comparison with the clathrin-binding proteins revealed a putative clathrin box, 199-LFPAD-203, at the C terminus of HDAg-L (Fig. 1C). Previous studies demonstrated that the N-terminal 100 amino acid residues are required for CHC to interact with the conserved clathrin box of its adaptor proteins (10). To examine whether the N-terminal domain of CHC is responsible for the interaction between CHC and HDAg-L, a recombinant His-CHC1-107 protein was generated, purified, and used to perform a pull-down assay with GST-HDAg-L(198-210). As shown in Fig. 1D, GST-HDAg-L(198-210) specifically pulled down the purified His-CHC1-107. In addition, the specific interaction was abolished when L199A and D203A mutations were independently introduced into the conserved residues of the putative clathrin box of HDAg-L. These results indicate that HDAg-L interacts directly in vitro with the N-terminal domain of CHC (CHC1-107) through the clathrin box.

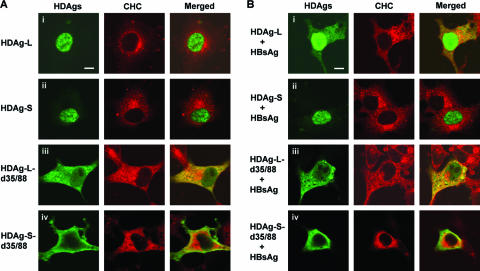

Colocalization of cytoplasmic HDAg-L with CHC in cytosol.

Clathrin forms coated pits in the plasma membrane and coated vesicles throughout the cytoplasm of the cell (36, 43). To examine the relative distribution of HDAgs and CHC in mammalian cells, COS7 cells were transfected independently with plasmids encoding wild-type HDAgs or cytoplasm-localized HDAgs, HDAg-L-d35/88, and HDAg-S-d35/88, from which the NLSs spanning amino acid residues 35 to 88 had been deleted. The expression of the HDAgs was examined under a confocal microscope (Fig. 2). Consistent with our previous findings (24), both wild-type HDAg-L and HDAg-S localized to the nucleus (Fig. 2A, panels i and ii). In the presence of small HBsAg, a small fraction of HDAg-L relocalized to the cytoplasm, but this was not observed for HDAg-S (Fig. 2B, panels i and ii). While endogenous CHC is exclusively cytosolic, cytoplasmic HDAg-L colocalized with endogenous CHC (Fig. 2B, panel i), but nucleus-localized HDAg-L and HDAg-S did not (Fig. 2A, panels i and ii, and Fig. 2B, panel ii). Similar to cytoplasm-localized wild-type HDAg-L as shown in Fig. 2B, panel i, NLS-deleted HDAg-L (HDAg-L-d35/88) colocalized with CHC in the cytoplasm independent of the presence of HBsAg (Fig. 2A and B, panels iii). On the other hand, colocalization of NLS-deleted HDAg-S (HDAg-S-d35/88) with CHC was not detected around the perinucleus where the HDV assembly may occur (Fig. 2A and B, panels iv). These results imply a critical role for the clathrin box unique to HDAg-L, but not HDAg-S, in the colocalization of cytoplasmic HDAg-L and CHC and the assembly of HDV. To better understand the specific areas of the cytoplasm where HDAg-L and CHC colocalized in the presence of HBsAg, CHC and HDAg-L were costained with specific subcellular markers, such as Golgin-245 for TGN, calnexin for endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and Alexa 594-conjugated CTx for the plasma membrane. As shown in Fig. 3, HDAg-L and CHC were mainly colocalized at TGN but not ER. In addition, both HDAg-L and CHC were barely detected on the plasma membrane, possibly because the ligand-induced clathrin-mediated endocytosis on the plasma membrane is a highly dynamic process.

FIG. 2.

Subcellular localization of HDAgs and endogenous CHC. COS7 cells were cotransfected with plasmids encoding different forms of HDAgs and small HBsAg as indicated. Expression of HDAgs was examined by immunofluorescence staining with antibodies against HDAgs and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat immunoglobulin G as shown in green under a Leica TCS SP2 confocal immunofluorescence microscope. Endogenous CHC was examined with anti-CHC antibody and Cy3-conjugated goat immunoglobulin G as shown in red. The merged images are shown on the right panels. Each bar on the images represents 20 μm in length.

FIG. 3.

Colocalization of CHC and cytoplasmic HDAg-L at TGN. COS7 cells (A) and cells cotransfected with plasmids encoding HDAg-L and small HBsAg (B) were fixed 2 days posttransfection with formaldehyde and analyzed by immunofluorescence staining with antibodies against CHC, HDAg, Golgin-245 (TGN marker), and Calnexin (ER marker) as indicated. Alexa 594-conjugated CTx, which was used as a marker for the plasma membrane, was preincubated with the cells 5 min before fixation. The images were examined under a Leica TCS SP2 confocal immunofluorescence microscope.

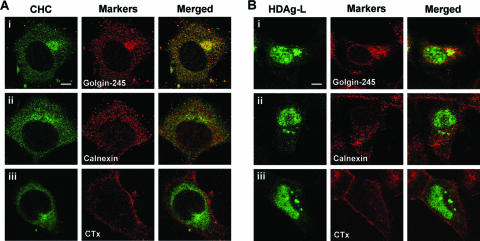

Coimmunoprecipitation and cosedimentation of HDAg-L and endogenous CHC in the presence of HBsAg.

The specific association of HDAg-L and CHC in vivo was examined by coimmunoprecipitation experiments. As shown in Fig. 4A, cytoplasm-localized HDAg-L-d35/88 expressed in COS7 cells could be coimmunoprecipitated with endogenous CHC (Fig. 4A, lane 3). Neither nucleus-localized wild-type HDAg-L possessing the clathrin box (Fig. 4A, lane 1) nor nucleus-localized wild-type HDAg-S and cytoplasm-localized HDAg-S-d35/88 lacking the clathrin box (Fig. 4A, lanes 2 and 4) formed complexes with CHC. In the presence of small HBsAg, cytoplasm-localized wild-type HDAg-L was coimmunoprecipitated with endogenous CHC (Fig. 4B, lane 1). Altogether, the colocalization and coimmunoprecipitation suggest the existence of a specific interaction between CHC and cytoplasmic HDAg-L in the same cellular compartment of mammalian cells. The interaction is dependent on the clathrin box and the cytoplasm localization of HDAg-L.

FIG. 4.

Coimmunoprecipitation and cosedimentation of HDAg-L and endogenous CHC in the presence of HBsAg. (A and B) Coimmunoprecipitation-Western blot analysis. COS7 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding HDAgs and HBsAg as indicated. Coimmunoprecipitation of HDAgs and CHC in the absence (A) or presence (B) of small HBsAg was performed with anti-CHC antibody followed by Western blot analysis with antibodies against CHC and HDAgs as indicated. Small HBsAg secreted into culture medium in the forms of HBV- and HDV-like particles was detected by Western blotting, with anti-HBsAg antibodies used as a control. Molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) are indicated on the left. (C) Cosedimentation of CHC, TfR, and HDAg-L. COS7 control cells and stable cell lines expressing HDAg-L (COS7-L1) and HDAg-S (COS7-S8) were transfected with plasmid encoding small HBsAg. Three days posttransfection, total cell lysates were prepared and separated on a 10% to 40% sucrose gradient. Cells without coexpression of HBsAg were analyzed in parallel as controls. Aliquots of individual fractions were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against CHC, HDAgs, and TfR as indicated.

Sucrose gradient centrifugation was applied to further investigate the association of CHC and HDAg-L. Protein lysates were prepared from an HDAg-L stable cell line (L1 cells), an HDAg-S stable cell line (S8 cells), and the parental COS7 cells in the presence or absence of HBsAg. Following fractionation, Western blot analysis was carried out with antibodies against CHC, HDAgs, and TfR known to be concentrated constitutively in clathrin-coated pits. As shown in Fig. 4C, endogenous CHC was detected universally from fractions 6 to 9, with the peak at fraction 7, for all cell lines and conditions examined. TfR had a broad range of distribution while enriched in the CHC-containing fractions. In the absence of small HBsAg, both wild-type HDAg-L and HDAg-S were distributed widely from fractions 11 to 18, a pattern independent of the distribution of CHC. Interestingly, distribution of wild-type HDAg-L, but not HDAg-S, became enriched in CHC and TfR-codistributed fractions 7 and 8 when small HBsAg was coexpressed (Fig. 4C, middle and bottom panels). The cosedimentation of HDAg-L and CHC in the presence of small HBsAg is in agreement with the observations that HDAg-L colocalized (Fig. 2B, panel i) and interacted with endogenous CHC in mammalian cells (Fig. 4B). The results also indicate an association between the CHC-HDAg-L complex and clathrin-coated pits.

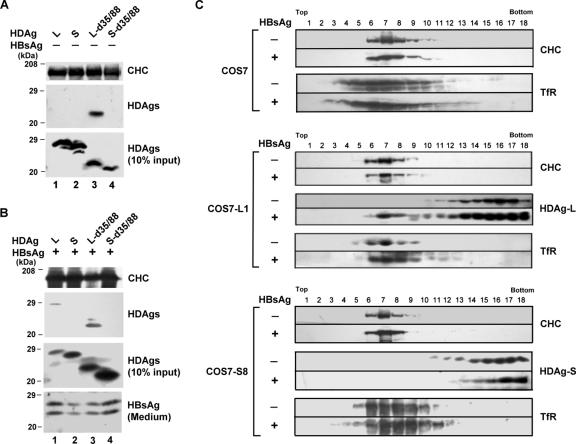

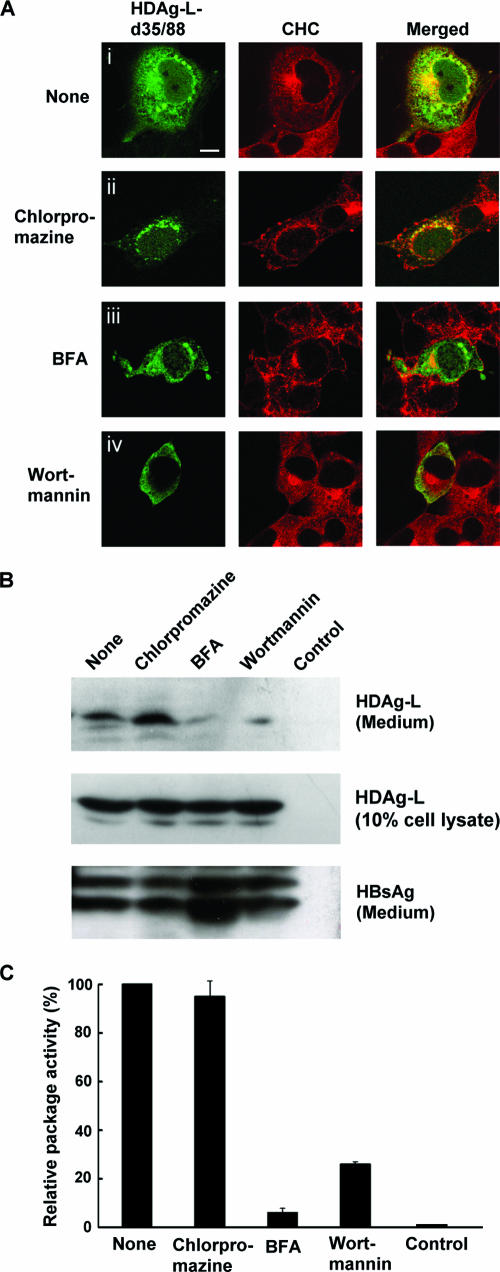

Effects of chlorpromazine, BFA, and wortmannin on HDV assembly.

To examine potential roles for CHC in regulating the assembly of HDV, inhibitors that block the clathrin-mediated protein transport pathway at different steps were applied: (i) brefeldin A (BFA), which induces changes in Golgi structure and inhibits recruitment of cytosolic clathrin adaptors onto Golgi membranes; (ii) wortmannin, which can dramatically reduce the number of internal endosome vesicles (42); and (iii) chlorpromazine, which affects the assembly of the clathrin-coated pit at the plasma membrane and is an inhibitor of clathrin-mediated endocytosis (46). As shown in Fig. 5A, CHC and NLS-deleted HDAg-L remained to be colocalized at the perinucleus when cells were pretreated with chlorpromazine (Fig. 5A, panel ii), but the distribution at other areas of the cytoplasm was less than that for the untreated cells (Fig. 5A, panel i). These results indicate that chlorpromazine may have effects on the colocalization of cytoplasmic HDAg-L and CHC on the plasma membrane but not TGN. On the other hand, when BFA, which blocks protein export from TGN, was used to treat the transfected cells, the perinuclear colocalization pattern was disrupted (Fig. 5A, panel iii). In addition, wortmannin-treated cells showed a mislocalization of NLS-deleted HDAg-L and failed to be codistributed with endogenous CHC in the cytoplasm (Fig. 5A, panel iv). Taken together, these data indicate a strong association between cytoplasm-localized HDAg-L and CHC at TGN.

FIG. 5.

Effects of chlorpromazine, BFA, and wortmannin on HDV assembly. (A) Immunofluorescence staining. COS7 cells were transfected with plasmid encoding cytoplasm-localized HDAg-L-d35/88. Two days posttransfection, cells were treated with chlorpromazine (10 μg/ml), BFA (1 μM), or wortmannin (100 nM) for 1 h at 37°C as indicated and processed for double immunofluorescence staining. Expression of HDAg-L-d35/88 and endogenous CHC was examined with antibodies as described in the legend to Fig. 2. The merged images are shown on the right panels. The bar indicated is 20 μm in length. (B and C) Package activity of HDAg-L in the presence of inhibitors. Two days following transfection of COS7 cells with HDAg-L-encoding plasmid, chlorpromazine (10 μg/ml), BFA (10 nM), and wortmannin (100 nM) were independently added into the culture media. At day 4 posttransfection, VLPs released into the culture media were collected and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HDAg and anti-HBsAg antibodies. Ten percent each of the total cell lysates was analyzed in parallel for the expression of HDAg-L as controls. Relative package activities, expressed as percentages of the package activity in the nontreated (None) control, were calculated. The data shown in panel C are the means and standard deviations for three independent experiments. “Control” represents the protein lysate prepared from COS7 cells without transfection.

The effects of the inhibitors on the assembly of HDV were further addressed by treating cells coexpressing HDAg-L and small HBsAg with the inhibitors and examining the presence of hepatitis delta VLPs in culture media. As shown in Fig. 5B, chlorpromazine had little effect on the generation of VLPs as detected by the level of HDAg-L present in the culture media. In contrast, the package activity decreased to about 26% in wortmannin-treated cells and to about 9% in BFA-treated cells (Fig. 5B and C). The effects of BFA and wortmannin on HDV assembly correlated with the inhibitory effects of the inhibitors on the interaction between HDAg-L and CHC as detected by coimmunoprecipitation experiments (data not shown). Taken together, these results indicate that colocalization of CHC and HDAg-L at TGN and endosomes is important for HDV maturation. Interestingly, none of the inhibitors interfered with the assembly of hepatitis B VLPs (Fig. 5B).

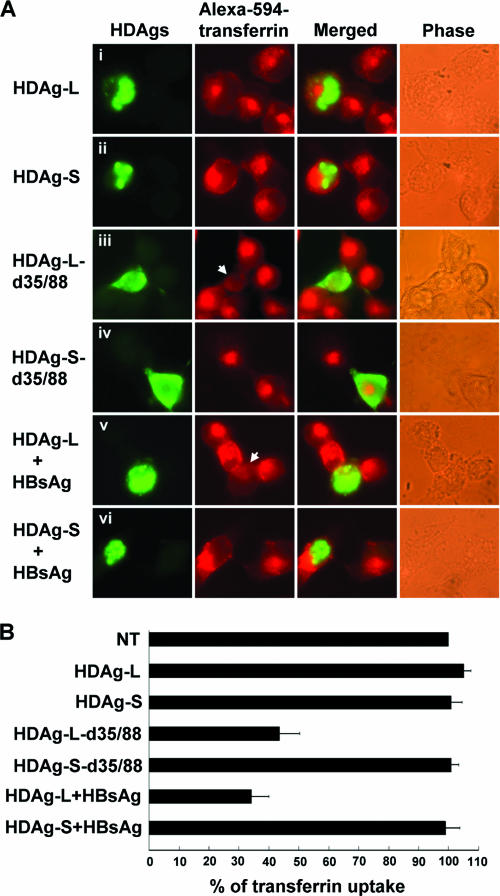

Cytoplasm-localized HDAg-L interferes with clathrin-mediated endocytosis of transferrin.

Clathrin is known to be involved in receptor-mediated endocytosis on the plasma membrane and vesicle transport from the TGN to the lysosome (43). Since transferrin is a well-studied ligand that is endocytosed through the clathrin-coated pits (28), a transferrin uptake assay was performed to directly assess whether HDAg-L would interfere with clathrin-mediated endocytosis. COS7 cells were transfected with HDAg-expressing plasmids in the presence or absence of HBsAg. Two days posttransfection, cells were treated with Alexa 594-conjugated transferrin and subjected to immunofluorescence staining with antibodies against HDAgs. As shown in Fig. 6, efficient transferrin uptake was observed in cells expressing HDAg-L, HDAg-S, or HDAg-S-d35/88 or coexpressing HDAg-S and HBsAg. In contrast, internalization of transferrin decreased to about 43% in cells expressing cytoplasm-localized HDAg-L-d35/88 and to about 34% in cells coexpressing HDAg-L and HBsAg. These results indicate that cytoplasm-localized HDAg-L may functionally block the clathrin-mediated endocytosis in mammalian cells through the CHC-binding site at its unique C-terminal domain. The failure of cytoplasm-localized HDAg-L to completely diminish the uptake of transferrin may be due to endocytosis mediated by a clathrin-independent pathway as described previously (37).

FIG. 6.

Effects of HDAgs on the internalization of transferrin. (A) The uptake of Alexa 594-conjugated transferrin in the presence of HDAgs. Two days following a transfection of plasmids encoding HDAgs and HBsAg as indicated, COS7 cells were treated with Alexa 594-conjugated transferrin for 20 min. The cells were then fixed, immunostained with anti-HDAg antibodies, and visualized using fluorescence microscopy. Right panels show the phase-contrast micrographs. Arrows indicate the transfected cells. (B) Quantification of transferrin uptake. The intensities of the Alexa 594-conjugated transferrin signals from 10 transfected cells were quantified in each set. The mean intensity was calculated and normalized against that of the nontransfected cells (NT). The graph represents the mean values for three independent experiments.

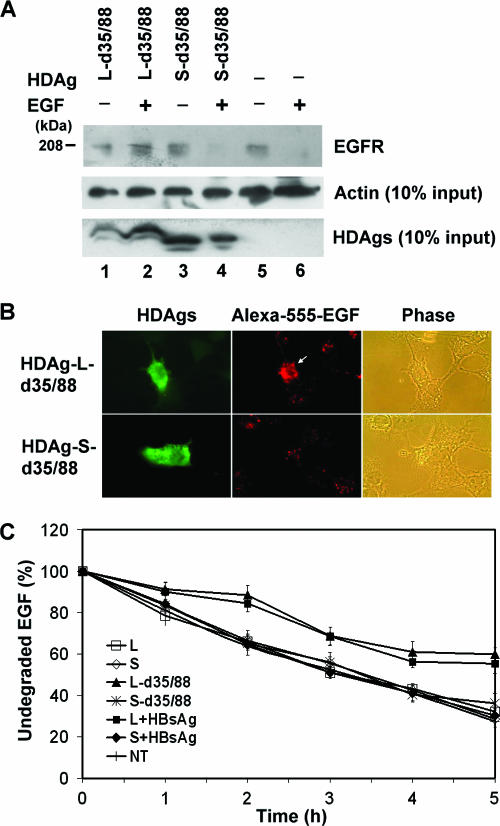

Cytoplasm-localized HDAg-L delays the rate of ligand-induced EGFR degradation.

Upon EGF induction, the canonical EGFR endocytosed and transferred to late endosomes for degradation. The process is clathrin-dependent (42). Since previous studies have demonstrated an inhibitory effect of overexpressed clathrin adaptors on the degradation of EGFR (36), possible effects of cytoplasm-localized HDAg-L interfering with the sorting of EGFR for transportation to the late endocytic compartment were examined in this study. COS7 cells were transfected with HDAg-encoding plasmids and stimulated with Alexa 555-conjugated EGF 2 days posttransfection. EGF-induced EGFR degradation was examined by immunoprecipitation-Western blot analysis with antibodies against EGFR and by quantitation of the EGFR-associated Alexa 555-conjugated EGF images. As shown in Fig. 7A, EGFR was mostly degraded in mock-transfected (Fig. 7A, lane 6) and HDAg-S-d35/88-expressing (Fig. 7A, lane 4) cells upon EGF stimulation. In contrast, significant amounts of EGFR (Fig. 7A, lane 2) and Alexa 555-conjugated EGF (Fig. 7B) were detected in cells expressing HDAg-L-d35/88. These results indicate that cytoplasm-localized HDAg-L down-regulated the degradation of EGFR. The kinetics of EGFR degradation was further examined by measuring the degradation rate of the EGFR-associated Alexa 555-conjugated EGF. As shown in Fig. 7C, a significantly lower turnover rate for EGF in cells expressing HDAg-L-d35/88 (half-life, >5 h) than for that in cells expressing HDAg-S-d35/88 (half-life, ∼3.3 h) was observed. Coexpression of small HBsAg and HDAg-L also reduced the turnover rate of EGF to a level comparable to that for cytoplasm-localized HDAg-L-d35/88, whereas the turnover rates of EGF in cells expressing nucleus-localized HDAg-L and HDAg-S were similar to those in the HDAg-S-d35/88-expressing cells and the nontransfected control cells (Fig. 7C). These data suggest that the interaction between CHC and cytoplasm-localized HDAg-L may interfere with the clathrin-mediated trafficking of a ligand-bound receptor from early to late endosomes.

FIG. 7.

Effects of HDAgs on the degradation of EGF-EGFR complexes. COS7 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding HDAgs and HBsAg as indicated. Two days posttransfection, the cells were starved, treated with Alexa 555-conjugated EGF for 20 min, and incubated in DMEM containing cycloheximide for 5 h as described in Materials and Methods. The cells were harvested for immunoprecipitation with antibodies against EGFR, followed by Western blot analysis with antibodies as indicated (A) or immunofluorescence analysis with antibodies specific to HDAgs (B). In addition, the intensities of the Alexa 555-conjugated EGF signals from 10 transfected cells were quantified at 1-h intervals during the 5-h incubation (C). The data are presented as percentages of undegraded EGF. NT represents the nontransfected cell control.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have provided the first evidence that HDAg-L is a clathrin adaptor-like protein. The direct and specific interaction between cytoplasmic HDAg-L and CHC demonstrated in vitro and in vivo indicates that CHC is a bona fide host cellular binding partner of HDAg-L. The N-terminal domain of CHC from amino acid residues 1 to 107 is sufficient for its direct interaction with the putative clathrin box at the unique C terminus of HDAg-L. The putative clathrin box can be found in both genotype I (199-LFPAD-203) and genotype II (206-LPLLE-210) HDAg-L (15). Leu-199 and Asp-203 of genotype I HDAg-L play indispensable roles in the interaction. In addition, the interaction of HDAg-L with clathrin at TGN facilitates HDV assembly. Further studies demonstrated that cytoplasm-localized HDAg-L can functionally inhibit clathrin-mediated protein endocytosis and trafficking. It remains to be examined whether the putative clathrin box of genotype II HDAg-L has functional roles similar to that of genotype I HDAg-L as demonstrated in this study.

HDAg-L shuttles from the nucleus to the cytoplasm (24) and associates with cytoplasmic small HBsAg (17, 44). Results from the present study (Fig. 2 to 4) indicate that HDAg-L translocating to the cytoplasm may form complexes and colocalize with endogenous CHC. Conceivably, interaction with CHC may be related to the cytoplasmic localization of HDAg-L. In addition, we demonstrated that assembly of HDV with small HBsAg could be inhibited by a down-regulation of the clathrin-mediated protein export pathway (Fig. 5). Accordingly, we speculate that the interaction between HDAg-L and CHC described herein is functionally important in events guiding the assembly and release of HDV. Clathrin-mediated exocytosis is likely to be a specialized way of HDV assembly. It ensures a fast and specific retrieval of virion formation and may be regulated by a magnitude of accessory factors. However, it remains to be determined whether HDAg-L can function as an adaptor protein for conferring the sorting of special host cellular cargoes and the assembly and disassembly of clathrin.

The mechanisms responsible for the entry and release of HDV from cells coinfected or superinfected with HBV are poorly understood. Previous non-HDV studies have addressed several mechanisms involved in the endocytic internalization of animal viruses, such as adenovirus, influenza virus, reovirus, simian virus 40, and echovirus 1. The mechanisms include macropinocytosis, the clathrin-mediated pathway, the clathrin-independent pathway, the caveolar-dependent pathway, the cholesterol-dependent pathway, and the dynamin-2-dependent pathway (27). The clathrin-dependent pathway is the most common pathway for viral infection, but little is known about the utilization of clathrin-mediated protein transport for viral assembly. In addition, hepadnaviruses have been proposed to bud intracellularly at post-ER, pre-Golgi (intermediate) membranes and/or proximal Golgi membranes (2, 3, 16, 41, 50). Identification of the interaction between HDAg-L and CHC in this study indicates a role for clathrin in the life cycle of HDV and raises a new issue regarding utilization of host transport machinery in viral assembly. In Fig. 5, we demonstrated that chlorpromazine, an inhibitor of clathrin-mediated endocytosis, had no effects on the packaging activity of HDV. Nevertheless, the packaging activity of HDV was inhibited by BFA and wortmannin. On the other hand, neither BFA nor wortmannin affected the assembly of small HBsAg. According to the findings from the current study and our previous studies (24, 47), we propose that small HBsAg may form 22-nm subviral particles at post-ER, pre-Golgi (intermediate) membranes and/or proximal Golgi membranes, but not TGN, and secrete from cells. On the other hand, HDAg-L forms complexes with HDAg-S and viral genomic RNA (vRNPs) in the nucleus. It directs the vRNPs to the cytoplasm and forms infectious particles with HBsAg via interaction with CHC in the TGN lumen. HDV exit is mediated by the exocytosis of clathrin-coated vesicles. Molecular mechanisms involved in clathrin-mediated assembly and exocytosis of HDV need to be further elucidated.

Clathrin and adaptor proteins constitute the major components of the coated pits in host cells (35). Adaptor proteins, which are highly conserved among diverse species, recruit cargoes through the clathrin box to coated pits (10). The putative clathrin box of HDAg-L identified in this study may compete for the binding of adaptor proteins to the CHC and result in a perturbation of clathrin-mediated endocytosis, trafficking, and exocytosis of host proteins. This hypothesis was first confirmed by the study of transferrin uptake in mammalian cells (Fig. 6). Under normal physiological conditions, uptake of cellular iron is regulated by the clathrin-mediated transferrin/TfR pathway. Expression of cytoplasm-localized HDAg-L reduced the transferrin internalization, presumably resulting from the interference of CHC functions on the plasma membrane. In addition, cytoplasm-localized HDAg-L can inhibit the trafficking of a ligand-bound EGFR from early to late endosomes for degradation (Fig. 7). On the other hand, since clathrin was demonstrated to be important for cell growth and secretion of proteins, including invertase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (13, 31), the yeast system was also applied to examine the possible effects of HDAg-L(198-210) on invertase production and secretion (data not shown). When sucrose was used as the sole carbon source, invertase was induced, rapidly transported to the plasma membrane, and released into the medium of wild-type yeast culture. Nevertheless, invertase secretion was blocked in the yeast clone expressing HDAg-L(198-210). Altogether, these data support the hypothesis that HDAg-L competes with clathrin-associated adaptor proteins in binding to CHC. The association of cytoplasm-localized HDAg-L with CHC may shift CHC into an inactive state in which it is no longer available to recruit cargoes and other components to form functional coated pits. The interaction may also lead to a hyperrecruitment or sequestration of CHC to different subcellular localizations that are no longer capable of regulating endosomal docking and motility.

HDV can dramatically worsen liver disease in patients coinfected or superinfected with HBV, but currently, there is no effective medical therapy for HDV-related chronic hepatitis. In this study, we have provided several lines of evidence that cytoplasmic HDAg-L interacts with host factor CHC in a highly specific manner. While functional roles for the clathrin-HDAg-L interaction in natural HDV infection await further clarification, our data indicate that HDV can disrupt clathrin-mediated protein transport. Clathrin-depleted cells were found to have a lower growth rate, but an increase in apoptosis was not observed (29). Otherwise, clathrin is important for effective cytokinesis through construction of a functional contractile ring during cell division (30). Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis revealed a progressive decline in the percentage of HDAg-positive cells due to growth disadvantage instead of apoptosis (45). Cirrhosis development without nodular regeneration was observed in liver biopsy samples of HDV patients (40). Therefore, the inhibitory effects of cytoplasmic HDAg-L on the biological functions of clathrin would be expected to impair liver regeneration, resulting in progressive chronic liver disease. Nevertheless, no pathogenesis was observed in transgenic mice expressing HDAg-S or HDAg-L alone (14). It is possible that in the absence of HBsAg, both HDAgs localized to the nucleus in transgenic mice. As we have demonstrated in this study, only cytoplasm-localized, not nucleus-localized, HDAg-L blocks clathrin-mediated protein transport, and these results indicate that different subcellular localizations of HDAg-L may contribute differently to viral pathogenesis. Furthermore, understanding the molecular mechanisms of HDAg-L involved in the life cycle of HDV will allow us to comprehend the biological roles of HDV in human liver diseases. The present study also suggests HDAg-L as a new molecular target in treating disorders associated with liver injury and cirrhosis of HDV infection.

Acknowledgments

We thank F. J. Lee (National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan) and T. L. Tseng (National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan) for reagents and helpful comments on this paper. We also thank C. L. Chien (National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan) for his guidance on confocal microscopy.

This work was supported in part by research grants NSC94-2320-B-002-021 and NSC94-2752-B-002-009-PAE from the National Science Council and by the Program for Promoting Academic Excellence of Universities under grant number 89-B-FA01-1-4 from the Ministry of Education, Republic of China.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 21 March 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bonino, F., K. H. Heermann, M. Rizzetto, and W. H. Gerlich. 1986. Hepatitis delta virus: protein composition of delta antigen and its hepatitis B virus-derived envelope. J. Virol. 58:945-950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruss, V. 1997. A short linear sequence in the pre-S domain of the large hepatitis B virus envelope protein required for virion formation. J. Virol. 71:9350-9357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruss, V., and D. Ganem. 1991. The role of envelope proteins in hepatitis B virus assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:1059-1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang, F. L., P. J. Chen, S. J. Tu, C. J. Wang, and D. S. Chen. 1991. The large form of hepatitis delta antigen is crucial for assembly of hepatitis delta virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:8490-8494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang, M. F., S. C. Baker, L. H. Soe, T. Kamahora, J. G. Keck, S. Makino, S. Govindarajan, and M. M. Lai. 1988. Human hepatitis delta antigen is a nuclear phosphoprotein with RNA-binding activity. J. Virol. 62:2403-2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang, M. F., S. C. Chang, C. I. Chang, K. Wu, and H. Y. Kang. 1992. Nuclear localization signals, but not putative leucine zipper motifs, are essential for nuclear transport of hepatitis delta antigen. J. Virol. 66:6019-6027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang, M. F., C. H. Chen, S. L. Lin, C. J. Chen, and S. C. Chang. 1995. Functional domains of delta antigens and viral RNA required for RNA packaging of hepatitis delta virus. J. Virol. 69:2508-2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang, M. F., C. J. Chen, and S. C. Chang. 1994. Mutational analysis of delta antigen: effect on assembly and replication of hepatitis delta virus. J. Virol. 68:646-653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glenn, J. S., J. A. Watson, C. M. Havel, and J. M. White. 1992. Identification of a prenylation site in delta virus large antigen. Science 256:1331-1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodman, O. B., Jr., J. G. Krupnick, V. V. Gurevich, J. L. Benovic, and J. H. Keen. 1997. Arrestin/clathrin interaction. Localization of the arrestin binding locus to the clathrin terminal domain. J. Biol. Chem. 272:15017-15022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goto, T., N. Kato, S. K. Ono-Nita, H. Yoshida, M. Otsuka, Y. Shiratori, and M. Omata. 2000. Large isoform of hepatitis delta antigen activates serum response factor-associated transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 275:37311-37316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goto, T., N. Kato, H. Yoshida, M. Otsuka, M. Moriyama, Y. Shiratori, K. Koike, M. Matsumura, and M. Omata. 2003. Synergistic activation of the serum response element-dependent pathway by hepatitis B virus x protein and large-isoform hepatitis delta antigen. J. Infect. Dis. 187:820-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graham, T. R., and V. A. Krasnov. 1995. Sorting of yeast alpha 1,3 mannosyltransferase is mediated by a lumenal domain interaction, and a transmembrane domain signal that can confer clathrin-dependent Golgi localization to a secreted protein. Mol. Biol. Cell 6:809-824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guilhot, S., S. N. Huang, Y. P. Xia, N. La Monica, M. M. Lai, and F. V. Chisari. 1994. Expression of the hepatitis delta virus large and small antigens in transgenic mice. J. Virol. 68:1052-1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsu, S. C., J. C. Wu, I. J. Sheen, and W. J. Syu. 2004. Interaction and replication activation of genotype I and II hepatitis delta antigens. J. Virol. 78:2693-2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huovila, A. P., A. M. Eder, and S. D. Fuller. 1992. Hepatitis B surface antigen assembles in a post-ER, pre-Golgi compartment. J. Cell Biol. 118:1305-1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hwang, S. B., and M. M. Lai. 1993. Isoprenylation mediates direct protein-protein interactions between hepatitis large delta antigen and hepatitis B virus surface antigen. J. Virol. 67:7659-7662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hwang, S. B., and K. J. Park. 1999. Cell cycle arrest mediated by hepatitis delta antigen. FEBS Lett. 449:41-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirchhausen, T. 2000. Clathrin. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:699-727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Komla-Soukha, I., and C. Sureau. 2006. A tryptophan-rich motif in the carboxyl terminus of the small envelope protein of hepatitis B virus is central to the assembly of hepatitis delta virus particles. J. Virol. 80:4648-4655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuo, M. Y., M. Chao, and J. Taylor. 1989. Initiation of replication of the human hepatitis delta virus genome from cloned DNA: role of delta antigen. J. Virol. 63:1945-1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lai, M. M. 1995. The molecular biology of hepatitis delta virus. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 64:259-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee, C. H., S. C. Chang, C. J. Chen, and M. F. Chang. 1998. The nucleolin binding activity of hepatitis delta antigen is associated with nucleolus targeting. J. Biol. Chem. 273:7650-7656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee, C. H., S. C. Chang, C. H. Wu, and M. F. Chang. 2001. A novel chromosome region maintenance 1-independent nuclear export signal of the large form of hepatitis delta antigen that is required for the viral assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 276:8142-8148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luo, G. X., M. Chao, S. Y. Hsieh, C. Sureau, K. Nishikura, and J. Taylor. 1990. A specific base transition occurs on replicating hepatitis delta virus RNA. J. Virol. 64:1021-1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macnaughton, T. B., E. J. Gowans, A. R. Jilbert, and C. J. Burrell. 1990. Hepatitis delta virus RNA, protein synthesis and associated cytotoxicity in a stably transfected cell line. Virology 177:692-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marsh, M., and A. Helenius. 2006. Virus entry: open sesame. Cell 124:729-740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mellman, I. 1996. Endocytosis and molecular sorting. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 12:575-625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Motley, A., N. A. Bright, M. N. Seaman, and M. S. Robinson. 2003. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis in AP-2-depleted cells. J. Cell Biol. 162:909-918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niswonger, M. L., and T. J. O'Halloran. 1997. A novel role for clathrin in cytokinesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:8575-8578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Payne, G. S., and R. Schekman. 1985. A test of clathrin function in protein secretion and cell growth. Science 230:1009-1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Polo, J. M., K. S. Jeng, B. Lim, S. Govindarajan, F. Hofman, F. Sangiorgi, and M. M. Lai. 1995. Transgenic mice support replication of hepatitis delta virus RNA in multiple tissues, particularly in skeletal muscle. J. Virol. 69:4880-4887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Polson, A. G., B. L. Bass, and J. L. Casey. 1996. RNA editing of hepatitis delta virus antigenome by dsRNA-adenosine deaminase. Nature 380:454-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Polson, A. G., H. L. Ley III, B. L. Bass, and J. L. Casey. 1998. Hepatitis delta virus RNA editing is highly specific for the amber/W site and is suppressed by hepatitis delta antigen. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:1919-1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Puertollano, R. 2004. Clathrin-mediated transport: assembly required. EMBO Rep. 5:942-946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raiborg, C., K. G. Bache, A. Mehlum, E. Stang, and H. Stenmark. 2001. Hrs recruits clathrin to early endosomes. EMBO J. 20:5008-5021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richardson, D. R., and P. Ponka. 1997. The molecular mechanisms of the metabolism and transport of iron in normal and neoplastic cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1331:1-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rizzetto, M. 1983. The delta agent. Hepatology 3:729-737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rizzetto, M., M. G. Canese, S. Arico, O. Crivelli, C. Trepo, F. Bonino, and G. Verme. 1977. Immunofluorescence detection of new antigen-antibody system (delta/anti-delta) associated to hepatitis B virus in liver and in serum of HBsAg carriers. Gut 18:997-1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rizzetto, M., G. Verme, S. Recchia, F. Bonino, P. Farci, S. Arico, R. Calzia, A. Picciotto, M. Colombo, and H. Popper. 1983. Chronic hepatitis in carriers of hepatitis B surface antigen, with intrahepatic expression of the delta antigen. An active and progressive disease unresponsive to immunosuppressive treatment. Ann. Intern. Med. 98:437-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roingeard, P., S. L. Lu, C. Sureau, M. Freschlin, B. Arbeille, M. Essex, and J. L. Romet-Lemonne. 1990. Immunocytochemical and electron microscopic study of hepatitis B virus antigen and complete particle production in hepatitis B virus DNA transfected HepG2 cells. Hepatology 11:277-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sachse, M., S. Urbe, V. Oorschot, G. J. Strous, and J. Klumperman. 2002. Bilayered clathrin coats on endosomal vacuoles are involved in protein sorting toward lysosomes. Mol. Biol. Cell 13:1313-1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmid, S. L. 1997. Clathrin-coated vesicle formation and protein sorting: an integrated process. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 66:511-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sureau, C., C. Fournier-Wirth, and P. Maurel. 2003. Role of N glycosylation of hepatitis B virus envelope proteins in morphogenesis and infectivity of hepatitis delta virus. J. Virol. 77:5519-5523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang, D., J. Pearlberg, Y. T. Liu, and D. Ganem. 2001. Deleterious effects of hepatitis delta virus replication on host cell proliferation. J. Virol. 75:3600-3604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang, L. H., K. G. Rothberg, and R. G. Anderson. 1993. Mis-assembly of clathrin lattices on endosomes reveals a regulatory switch for coated pit formation. J. Cell Biol. 123:1107-1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang, Y. H., S. C. Chang, C. Huang, Y. P. Li, C. H. Lee, and M. F. Chang. 2005. Novel nuclear export signal-interacting protein, NESI, critical for the assembly of hepatitis delta virus. J. Virol. 79:8113-8120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wei, Y., and D. Ganem. 1998. Activation of heterologous gene expression by the large isoform of hepatitis delta antigen. J. Virol. 72:2089-2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weiner, A. J., Q. L. Choo, K. S. Wang, S. Govindarajan, A. G. Redeker, J. L. Gerin, and M. Houghton. 1988. A single antigenomic open reading frame of the hepatitis delta virus encodes the epitope(s) of both hepatitis delta antigen polypeptides p24 delta and p27 delta. J. Virol. 62:594-599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu, Z., V. Bruss, and T. S. Yen. 1997. Formation of intracellular particles by hepatitis B virus large surface protein. J. Virol. 71:5487-5494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]