Abstract

The functions of the human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) IE86 protein are paradoxical, as it can both activate and repress viral gene expression through interaction with the promoter region. Although the mechanism for these functions is not clearly defined, it appears that a combination of direct DNA binding and protein-protein interactions is involved. Multiple sequence alignment of several HCMV IE86 homologs reveals that the amino acids 534LPIYE538 are conserved between all primate and nonprimate CMVs. In the context of a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC), mutation of both P535 and Y537 to alanines (P535A/Y537A) results in a nonviable BAC. The defective HCMV BAC does not undergo DNA replication, although the P535A/Y537A mutant IE86 protein appears to be stably expressed. The P535A/Y537A mutant IE86 protein is able to negatively autoregulate transcription from the major immediate-early (MIE) promoter and was recruited to the MIE promoter in a chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay. However, the P535A/Y537A mutant IE86 protein was unable to transactivate early viral genes and was not recruited to the early viral UL4 and UL112 promoters in a ChIP assay. From these data, we conclude that the transactivation and repressive functions of the HCMV IE86 protein can be separated and must occur through independent mechanisms.

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a human herpesvirus that establishes a latent, lifelong infection. In a healthy host, HCMV infection is usually asymptomatic and is easily spread through body fluids. HCMV is also a significant human pathogen. Infection in utero is the leading infectious cause of birth defects and can lead to developmental disabilities. Retinitis, pneumonitis, hepatitis, encephalitis, and gastroenteritis can result from infection of an immunocompromised individual. HCMV also causes infectious mononucleosis and may be involved in atherosclerosis. The viral life cycle affects many cellular processes, including signal transduction, apoptosis, transcription, cell cycle, DNA replication, and immune response. For these reasons, the study of HCMV is important from the aspects of human disease, viral manipulation of cellular processes, and viral reactivation and replication.

The IE86 protein of HCMV, encoded by the IE2 transcript, is expressed at immediate-early times during infection. It is a large protein of 579 amino acids with an apparent molecular mass of 86 kDa. IE86 is a structurally complex, multifunctional protein that is essential for viral replication. Although the crystal structure of IE86 has not yet been determined, much is known about the sequence and functions of the viral protein. The sequence of IE86 contains two acidic activation domains, two independent nuclear localization signals (50), putative zinc fingers (67), and sites for phosphorylation (23) and sumoylation (2, 25). The functions of the IE86 protein include the ability to promote cell cycle progression (46, 63), inhibit cellular DNA synthesis (6, 56), repress the viral major immediate-early (MIE) promoter (9, 36, 49), activate multiple viral and cellular promoters (5, 41, 55), and inhibit cytokine and chemokine promoters (58, 59). It has also been implicated in antiapoptotic activities (69). The exact mechanisms for these functions are unclear, including the apparent conflicting functions of negative autoregulation and transactivation.

The HCMV MIE promoter, which expresses the IE1 and IE2 genes, contains a binding site for the IE86 protein. The site, referred to as the cis repression sequence (crs), consists of the nucleotides CG flanking each side of 10 AT-rich nucleotides (36). This 14-bp binding site resides between the TATA box and transcription start site of the MIE promoter (33). IE86 binds directly to the crs in a gel shift assay and does not prevent TATA binding protein (TBP) from binding to the MIE promoter TATA box (31). Furthermore, an IE86 mutant that does not interact with TBP is still able to bind to the crs, indicating that the ability to bind the MIE promoter in vitro is not dependent on a protein-protein interaction (64). This binding prevents recruitment of RNA polymerase II to the MIE promoter and thereby represses transcription of the IE1 and IE2 genes (35). The ability of IE86 to repress transcription from a promoter containing an IE86 binding site has also been demonstrated in the human insulin-like growth factor binding protein 4 gene (60), and the presence of IE86 binding sites in the promoters of other cellular genes that are repressed during HCMV infection has been described (68).

In direct contrast to the ability of IE86 to repress specific viral and cellular promoters, interaction with the promoters of other viral and cellular genes results in activation of those genes by IE86. IE86 is required during HCMV infection for its ability to transactivate early viral genes (42). The IE72 protein, encoded by the IE1 transcript, augments the transactivation of the early viral genes but is not required (18, 41). In addition to the viral genes, IE86 has been shown to directly transactivate several cellular promoters, including c-myc, c-fos, and Hsp70 (22). The cis-acting elements required for IE86-mediated transactivation are not well defined, but the existence of a TATA box appears to be necessary (21) and the presence of CCAAT, SP1, or Tef-1 binding sites appears to be preferable (37). While the need for a direct IE86 binding site has not been determined, there are crs-like binding sites in the early viral UL4 and UL112 promoters and the cellular cyclin E promoter (3, 5, 8, 26, 51, 52). The common involvement of a TATA box and a binding site for IE86 between the autoregulatory and transactivating functions of IE86 suggests that a common mechanism for these conflicting functions may exist.

Another common element between the autoregulatory and transactivating functions of IE86 is the C-terminal region of the protein (57). The region of IE86 required for negative autoregulation is between amino acids 290 and 579 (24) and includes the DNA binding domain (amino acids 346 to 579) (1, 10) and the dimerization domain (amino acids 388 to 542), which is required for DNA binding (39, 40). The region of IE86 required for transactivation is between amino acids 195 and 579, which includes the C-terminal activation domain (amino acids 544 to 579) (50). Interaction with TBP, a component of the TFIID complex, and interaction with TFIIB require amino acids 290 to 504 and 290 to 542, respectively (7, 21, 32). Recently, this apparent overlap in function was refined to amino acids 450 to 552, termed the “core domain” of IE86 (4). While the experiments used to establish the core domain of IE86 were not in the context of the viral genome, the authors concluded that mutations in the core domain could not be made without affecting all functions of the IE86 protein. It remains a mystery how two opposing functions can have so many shared features.

Using the core domain of IE86 as a starting point, we attempted to further investigate the functions and mechanisms of the viral protein. We began this study with three simple goals. The first goal was to identify specific regions within the core domain that may be critical for the function(s) of IE86. This was accomplished by multiple sequence alignment of HCMV IE86 with the IE2 homologs from other species CMVs. The second goal was to isolate mutants where the functions of IE86 have been separated from each other. This would allow us to study the protein functions independent of one another. Finally, we hoped to learn new information about the mechanisms of the paradoxical functions of IE86.

From these three simple goals, we believe that we have uncovered important insights into the structure of IE86 and the mechanisms for autoregulation and transactivation. We have identified a stretch of five amino acids in the core domain of IE86 that is conserved between all primate and nonprimate CMV IE86 homologs that were tested. Mutating two of those amino acids simultaneously results in a recombinant IE86 protein that is unable to transactivate early viral promoters but retains the ability to repress the MIE promoter. This demonstrates that it is possible to introduce mutations in the core domain of IE86 without disrupting all functions of the viral protein and that the autoregulatory and transactivating functions of IE86 can be separated and thus must utilize independent mechanisms for promoter binding. Finally, we propose that this mutation disrupts the TBP binding domain of IE86, resulting in the failure of the mutant IE86 protein to be recruited to early viral promoters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids and BACs.

The pSVCS plasmid, containing the MIE promoter and UL123-UL121, was described previously (41). The Stratagene QuikChange XL mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) was used to introduce point mutations into exon 5 of the IE2 gene in pSVCS, according to the manufacturer's instructions. The L534A amino acid mutation, and also a KasI restriction enzyme site, was introduced using the oligonucleotide 5′ CAG GGT GGG TTC ATG GCG CCT ATC TAC GAG ACG 3′ and its complementary oligonucleotide. The P535A/Y537A amino acid mutation, and also a MscI restriction enzyme site, was introduced using the oligonucleotide 5′ GGG TTC ATG CTG GCC ATC GCC GAG ACG GCC ACG 3′ and its complementary oligonucleotide. The H446A/H452A amino acid mutation, and also a Kas I restriction enzyme site, was introduced using the oligonucleotide 5′ CCC TTC CTC ATG GAA GCT ACC ATG CCC GTG ACG GCG CCA CCC AAA GTG GCG 3′ and its complementary oligonucleotide.

The pΔMCAT Δ-694/-583 plasmid, containing UL122-UL128 and including the UL127/CAT reporter, was described previously (34, 38). The plasmid pGEM-T-kan/lacZ, kindly provided by T. Shenk (Princeton University, New Jersey), was used to amplify the kanamycin resistance (Kanr) gene using the primers 5′ AAA AAG GAT CCT GTG TCT CAA AAT CTC 3′ and 5′ AAA AAG GAT CCT CCT TCA ACT CAG CAA 3′. The Kanr gene was digested with the BamHI restriction enzyme to generate sticky ends and inserted between the UL127/CAT and UL128 open reading frames (ORFs) of the pΔMCAT Δ-694/-583 plasmid at a BamHI site. The UL122-UL123 region of the pΔMCAT Δ-694/-583 plasmid was removed and replaced with UL121-UL123 of pSVCS containing the mutations described above. The final shuttle vectors pΔMCAT Δ-694/-583+Kanr+IE2 WT, pΔMCAT Δ-694/-583+Kanr+IE2 L534A, pΔMCAT Δ-694/-583+Kanr+IE2 P535A/Y537A, and pΔMCAT Δ-694/-583+Kanr+IE2 H446A/H452A were used for chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) assays and to construct recombinant BACs, as described below.

The pΔMCAT Δ-694/-583+Kanr+IE2 P535A/Y537A and pΔMCAT Δ-694/-583+Kanr+IE2 H446A/H452A plasmids were further manipulated to generate revertant (Rev) BACs. The plasmid pΩaacC4, kindly provided by T. Yahr (University of Iowa), was digested with BamHI to isolate the gentamicin resistance (Genr) gene. The Kanr gene was removed from pΔMCAT Δ-694/-583+Kanr+IE2 and replaced with the Genr gene at the BamHI sites. The P535A/Y537A mutation in exon 5 of the IE2 gene was reverted to wild type using the oligonucleotide 5′ GGG TTC ATG CTG CCT ATC TAC GAG ACG GCC ACG 3′ and its complementary oligonucleotide. The H446A/H452A mutation in exon 5 of the IE2 gene was reverted to wild type using the oligonucleotide 5′ CCC TTC CTC ATG GAG CAC ACC ATG CCC GTG ACA CAT CCA CCC AAA GTG GCG 3′ and its complementary oligonucleotide. The final shuttle vectors pΔMCAT Δ-694/-583+Genr+IE2 Rev-PY and pΔMCAT Δ-694/-583+Genr+IE2 Rev-HH were used for CAT assays and to construct a recombinant BAC, as described below.

The HCMV Towne BAC DNA was kindly provided by F. Liu and was described previously (14). Shuttle vectors were linearized by restriction digestion with NheI, and the UL121-128 fragment was gel purified. Recombinant BACs were generated using the linear UL121-UL128 fragment described above and homologous recombination with Towne BAC, in DY380 cells, as described previously (15). BAC DNA was isolated using the Nucleobond BAC maxiprep kit (BD Biosciences, Palo Alto, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cell culture and recombinant viruses.

Primary human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs) were isolated and grown in Eagle's minimal essential medium (Mediatech, Herndon, VA) supplemented with 10% newborn calf serum (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). 293 cells were grown in Dulbecco's minimal essential medium (Mediatech) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (JRH Biosciences, Lenexa, KS), penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml).

Recombinant viruses were isolated, propagated, and maintained as described previously (30). Briefly, HFF cells were transfected with 1 or 3 μg of each recombinant BAC and 1 μg of the plasmid pSVpp71 (simian virus 40 [SV40] promoter pp71) using the calcium phosphate precipitation method (17). Extracellular fluid was harvested 5 to 7 days after 100% cytopathic effect (CPE) and stored at −80°C in 50% newborn calf serum or passaged onto fresh HFF cells. Virus titers were determined by plaque assay, using equal viral DNA input from stored virus stocks, as described previously (29, 30).

Multiplex real-time PCR analysis.

HCMV gB DNA was detected and quantified using a multiplex real-time PCR for viral DNA replication assays. HFF cells were transfected, in triplicate, with 3 μg of recombinant BAC DNA for a viral DNA replication assay. Whole-cell DNA was harvested as described previously (28) at 1, 5, 9, and 13 days posttransfection. Multiplex real-time PCR was performed using 0.5 μg DNA in a final volume of 25 μl of the Platinum PCR Supermix-UDG cocktail (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). HCMV gB primers and 6-carboxyfluorescein-6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine (FAM-TAMRA) probe, described previously (28), and cellular 18S rRNA primers and VIC-TAMRA probe (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) were used simultaneously. Thermal cycling conditions and determination of relative quantification of gB DNA were performed as described previously (43).

HCMV RNA was detected and quantified using a multiplex real-time PCR for MIE autoregulation and early viral gene transactivation assays. HFF cells were transfected, in triplicate, with 5 μg of recombinant BAC DNA. Whole-cell RNA was harvested using TRI reagent (Invitrogen), treated with RNase-free DNase, and converted to cDNA as described previously (29). The multiplex real-time PCR was performed using 2 μl undiluted cDNA, or RNA lacking reverse transcriptase, in a final volume of 25 μl of the Platinum PCR Supermix-UDG cocktail (Invitrogen). Primers and FAM-TAMRA probes for HCMV MIE and TRS1 IE genes were described previously (43). Primers and FAM-TAMRA probes for HCMV UL44, UL54, and IRL7 early genes were previously described (48). Thermal cycling conditions and performance of relative quantification of HCMV RNA were as described previously (43). Threshold cycle values of samples not treated with reverse transcriptase did not differ appreciably from baseline.

Western blot analysis.

HFF cells were transfected with 5 μg of recombinant BAC DNA using the calcium phosphate precipitation method. Western blot analysis of viral proteins was performed as described previously (46). Briefly, cell lysates were harvested at 72 h posttransfection and fractionated on a 9% polyacrylamide-sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) gel. Proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane and Western blotting was performed using primary mouse monoclonal antibody 810 (Chemicon), to detect MIE proteins, or primary mouse monoclonal antibody E7 (University of Iowa Hybridoma Facility) to detect cellular β-tubulin. Proteins were detected using secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) and Pierce SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescence detection reagent (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Relative intensities of bands were quantified using the Kodak 1D software.

CAT assay.

Activation of the early UL127-CAT reporter was determined by CAT assay, as described previously (38). Briefly, HFF cells were transfected, in triplicate, with 3 μg IE86/CAT shuttle vector and 2 μg β-galactosidase (β-Gal) expression vector (SV40 promoter-β-Gal). Total protein was harvested at 3 days posttransfection. CAT assays were performed, and the percentage of acetylated [C14]chloramphenicol (Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA) was determined by image analysis. Bradford assays were performed to normalize the CAT activity per microgram of protein. β-Gal assays were performed to normalize the CAT activity for transfection efficiency.

Repression of the MIEP-CAT reporter and activation of the early UL4-CAT or UL112-CAT reporters was determined by CAT assay. 293 cells were transfected, in triplicate, with 2 μg pSVCS, containing either the WT or mutant IE2 gene, 3 μg pCAT760, containing the MIEP-CAT reporter, and 3 μg of β-Gal expression vector for repression of the MIEP. 293 cells were transfected with 2 μg pSVCS and 3 μg pUL4-CAT (−220 to +1 of UL4 promoter) or pUL112-CAT (−404 to +1 of UL112 promoter) for activation of an early promoter. Total protein was harvested at 2 days posttransfection. CAT, Bradford, and β-Gal assays were performed as described above.

ChIP assay.

A ChIP assay was performed as described previously (62), with the following modifications. HFF cells were transfected using the normal human dermal fibroblast kit and program U-20 on Nucleofector II from Amaxa Biosystems (Gaithersburg, MD), per the manufacturer's instructions. 293 cells were transfected using the calcium phosphate precipitation method, described above. Cells were transfected, in triplicate, with 5 μg pSVCS DNA, containing the MIE crs and the WT or mutant IE2 gene, for MIEP binding or 5 μg pSVCS DNA and 3 μg pUL4-CAT or pUL112-CAT for early promoter binding. Following cross-linking, transfected cells were suspended in cell lysis buffer [5 mM piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid), 85 mM KCl, 0.5% NP-40, 1× Roche Complete Mini protease inhibitor]. Nuclei were isolated, suspended in sonication buffer, and sonicated on ice for a total of 120 seconds at 25% amplitude using a 20-second pulse followed by a 20-second pause using a Virsonic 475 sonicator and microtip (Virtis, Gardiner, NY). Chromatin was precleared with a single-stranded DNA-protein G agarose slurry (Upstate). Precleared chromatin was incubated with 1 μg of rabbit polyclonal antibody to IE86 (6655; gift from J. Nelson, Oregon Health Sciences University), TBP (SI-1; sc-273; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or normal rabbit serum and immunoprecipitated with a protein G agarose-single-stranded DNA slurry. Immunoprecipitated DNA was resuspended in 50 μl water.

The MIE promoter was amplified from immunoprecipitated chromatin using the primers 5′ GGC GTG GAT AGC GGT TTG ACT CAC G 3′ and 5′ GCA TAA GAA GCC AAG GGG GTG GGC 3′, and nested PCR was performed using the primers 5′ CCA CCC CAT TGA CGT CAA TGG GAG 3′ and 5′ CTC TTG GCA CGG GGA ATC CCG CG 3′. The UL4 promoter was amplified from the immunoprecipitated chromatin using the primers 5′ GAG CGA CCG AGT TTT CTG GCA TGG 3′ and 5′ GCC GTA ATA TCC AGC TGA ACG GTC 3′, and nested PCR was performed using the primers 5′ GGA ATT CTC AGG GGA TGA TAT GGG 3′ and 5′ TCC ATT GGG ATA TAT CAA CGG TGG 3′. The UL112 promoter was amplified from the immunoprecipitated chromatin using the primers 5′GCA TAC TCT AGA GGC GCT GTC CGC 3′ and 5′ CCA AGC TTT GGA GCG AGT GCC GCC 3′, and nested PCR was performed using the primers 5′ GCA CGC TGT TTT ACT TTT GTC GGG 3′ and 5′ CAT CAT CTT TCC AGC CCG CCT AGC 3′.

Amplification of the desired promoter was performed using 10 μl of the immunoprecipitated DNA in a total reaction volume of 50 μl. Thermal cycling conditions were 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s, for a total of 30 cycles. The PCR product was visualized on an agarose gel using 20 μl of the PCR product, and the remaining 30 μl was purified with the QIAquick PCR purification kit and resuspended in 30 μl water. Nested PCR was performed using 10 μl of the purified PCR product in a total reaction volume of 50 μl. Thermal cycling conditions were the same as above. The nested PCR product was visualized on an agarose gel using 10 μl of the PCR product.

Equal expression of the MIE proteins from transfected cells was verified by Western blot analysis, described above, of ChIP lysates using a monoclonal antibody to IE72 (p63-27; a gift from B. Britt). The ability of the IP antibody (6655) to detect mutant IE86 proteins from transfected cells was verified by Western blot analysis of ChIP lysates.

RESULTS

Construction and replication of IE86 mutants.

In order to narrow our investigation of the “core” domain to amino acids that may be involved in the functions of the IE86 protein, we performed a multiple sequence alignment of the amino acids from HCMV IE86 and its primate and nonprimate homologs. A stretch of five amino acids in the C terminus of the “core” domain was identified that is conserved between all tested homologs (Fig. 1). The amino acids 534LPIYE538, based upon the human CMV sequence, represent the longest consecutive stretch of conserved amino acids within the “core” region and the second longest conserved stretch between all of the IE86 protein homologs (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Amino acids LPIYE/D are conserved in CMV IE86 protein homologs. Amino acid sequences for the proteins from human CMV, Towne strain, IE2 (AAR31449), chimpanzee CMV IE2 (NP612745), rhesus CMV IE2 (AAB00488), African green monkey (AGM) CMV IE2 (AAB16881), mouse CMV IE3 (AAA74505), and rat CMV IE2 (AAB92266) were aligned using MultAlin. Multiple sequence alignments are displayed using BoxShade. Identical residues appear shaded in black, while similar residues appear shaded in gray. In the consensus sequence, an asterisk indicates a residue that is identical in all aligned sequences, while a dot indicates a residue that is identical in at least half of the aligned sequences. The numbers appearing between the species and the amino acid sequence represent the amino acid position for that particular species. A hyphen designates a gap in the sequence that was inserted for optimal alignment.

We produced two mutants to test the significance of this region of HCMV IE86. First, we mutated the leucine at amino acid position 534 to an alanine (L534A), a conservative mutation that would essentially serve as a positive control for this study. Second, we mutated both the proline at amino acid position 535 and the tyrosine at 537 to alanines (P535A/Y537A), a more radical change that would assess the role of the conserved sequence in the functions of the IE86 protein. A third mutation of both the histidines at amino acid positions 446 and 452 to alanines (H446A/H452A) served as a negative control, as mutation of these histidines has previously been shown to produce a nonfunctional protein (40). These mutations were introduced into the IE2 gene of the Towne strain of HCMV to generate recombinant BACs, as described previously (48). The recombinant BACs also contained the modified early UL127 promoter driving the CAT reporter gene and a kanamycin resistance gene for selection of the recombinant BACs (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

Construction and confirmation of recombinant BACs. (A) Recombinant BACs were constructed by homologous recombination of a NheI-linearized DNA fragment with Towne BAC, kindly provided by F. Liu, University of California, Berkeley. UL121 and UL128 served as flanking regions to introduce targeted mutations into exon 5 of IE2. The UL127 locus was replaced by the CAT reporter, as described previously (34, 38). A kanamycin resistance (Kanr) cassette was inserted between UL127 and UL128 for selection of recombinant BACs. (B) The integrity of recombinant BACs was verified by digesting BAC DNA with the HindIII restriction enzyme. The presence of Kanr in IE86 mutants or the presence of gentamicin resistance (Genr) in IE86 revertants (Rev) is indicated. (C) Exon 5 of IE2 was amplified from the recombinant BACs by PCR and digested with the indicated restriction enzymes. Successful recombination of the P535A/Y537A mutation introduced a new MscI restriction site, while the H446A/H452A and L534A mutations introduced a new KasI restriction site, compared to WT.

In addition to sequencing of the IE2 gene and selection by antibiotic resistance, recombinant BACs were screened by two other methods. First, recombinant BACs were digested with the restriction enzyme Hind III to verify the integrity of BAC DNA (Fig. 2B). When compared to the parental Towne BAC, recombinant BACs containing WT, L534A, P5353A/Y537A, and H446A/H452A IE86 possessed an additional fragment of approximately 2.8 kbp, a result of the addition of the Kanr gene. Revertant BACs were constructed for the P535A/Y537A IE86 mutation (Rev-PY) and the H446A/H452A IE86 mutation (Rev-HH) by reversion of the mutation to wild-type sequence and replacing the Kanr gene with gentamicin resistance (Genr). Second, a new restriction enzyme site was introduced into the IE2 gene with each mutation. Exon 5 of the IE2 gene was amplified by PCR to produce a 1,100-bp PCR product, which was digested with the appropriate restriction enzyme. A unique MscI site was present in the P535A/Y537A IE86 mutant, while a unique KasI site was introduced with the L534A and H446A/H452A IE86 mutations (Fig. 2C).

Recombinant BACs were transfected into HFF cells and monitored for the production of recombinant virus. After 10 to 14 days, cells transfected with recombinant BACs containing WT, L534A, Rev-PY, or Rev-HH IE86 reached 100% CPE; the supernatant from those cells was analyzed by plaque assay, and all recombinant viruses reached similar titers (data not shown). Cells transfected with recombinant BACs containing P535A/Y537A or H446A/H452A mutant IE86 did not show any CPE during the same time period. After 8 weeks of stimulation by feeding and splitting the transfected cells, recombinant virus was not recovered from the P535A/Y537A or H446A/H452A mutations.

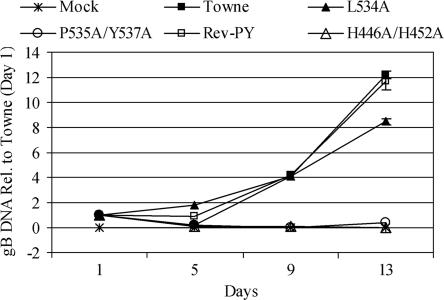

To determine whether the block in virus production occurred prior to or following viral DNA replication, HFFs were transfected with the recombinant BACs containing either WT or mutant IE86. Total DNA was harvested at 1, 5, 9, and 13 days posttransfection and analyzed for replication of HCMV gB DNA by real-time PCR. An equivalent amount of WT or mutant IE86 BAC DNA was detected at day 1. Relative to Towne (WT IE86) BAC DNA input at day 1, BAC DNA containing WT and Rev-PY IE86 increased approximately 12-fold by day 13 (Fig. 3). BAC DNA containing the L534A IE86 mutation increased approximately 8-fold by day 13 but was at similar levels as WT and Rev-PY IE86 at day 9. In contrast, there was no increase in the amount of gB DNA present from recombinant BACs containing the P535A/Y537A or H446A/H452A IE86 mutations at day 13. By day 28, there was still no detectable replication of these mutants (data not shown). This lack of viral DNA replication indicates that the defects in virus production from the P535A/Y537A and H446A/H452A mutant IE86 proteins occur at IE or early times during infection.

FIG. 3.

Recombinant BACs containing the P535A/Y537A and H446A/H452A IE86 mutations fail to replicate. HFF cells were transfected, in triplicate, with a viral pp71 expression vector and Towne (WT IE86), L534A, P535A/Y537A, Revertant (Rev)-PY, or H446A/H452A BAC DNA. Medium was changed on transfected cells every 4 days. Total DNA was harvested at 1, 5, 9, and 13 days posttransfection. Real-time PCR with primer/probe sets to detect HCMV gB DNA and cellular 18S rRNA genes was performed. BAC DNA replication was measured based on the amount of HCMV gB DNA, normalized to cellular 18S rRNA genes, relative to Towne-transfected cells at 1 day posttransfection. Mock samples contained pp71 but not BAC DNA.

Autoregulation of the viral MIE promoter.

We have previously shown that mutation of amino acid 548 from glutamine to arginine inhibited IE86-mediated cell cycle arrest without abolishing autoregulation, early viral gene expression, or viral replication (48). While each of the multiple functions of the viral protein play a role in efficient viral replication, the failure of IE86 to autoregulate its own expression has never been reported to be sufficient to inhibit viral replication. Thus, we were interested in whether the P535A/Y537A mutant IE86 protein was capable of repressing the MIE promoter, as this function has been mapped near the core region of IE86. A defect in autoregulation could be one factor in the lethality of this particular mutation.

Recombinant BACs encoding either WT or mutant IE86 were transfected into HFF cells, and viral MIE RNA (48 h) or protein (72 h) was analyzed by real-time PCR or Western blotting, respectively. Input viral DNA for WT and mutants was measured by real-time PCR analysis of gB DNA, as described in Materials and Methods. Viral DNA uptake by the HFF cells was equivalent (data not shown). Compared to WT IE86, the P535A/Y537A mutant IE86 protein was able to autoregulate expression from the MIE promoter at both RNA and protein levels (Fig. 4A and B). L534A and Rev-PY IE86 also expressed MIE RNA (data not shown) and protein (Fig. 4B) at levels similar to WT. In contrast, MIE RNA from the H446A/H452A mutant IE86 protein was nearly 3-fold higher than WT IE86, while IE86 and IE72 protein levels from the mutant were 3.1- and 3.3-fold higher than WT, respectively. Therefore, despite not being able to replicate, the presence of the P535A/Y537A mutation in IE86 had no significant effect on the autoregulatory function of the viral protein.

FIG. 4.

P535A/Y537A mutant IE86 protein is able to negatively autoregulate expression from the MIE promoter. (A) HFF cells were transfected, in triplicate, with a viral pp71 expression vector and WT, P535A/Y537A, or H446A/H452A recombinant BAC DNA. Total RNA was harvested at 48 h posttransfection and converted to cDNA by reverse transcription. Real-time PCR was performed with primer/probe sets to detect HCMV MIE cDNA and cellular 18S complementary rRNA genes. MIE RNA transcription was measured based on the amount of HCMV MIE cDNA, normalized to cellular 18S complementary rRNA genes, relative to WT. Mock samples contained pp71 but not BAC DNA. (B) HFF cells were transfected with a viral pp71 expression vector and WT, L534A, P535A/Y537A (PY), revertant-PY (Rev), or H446A/H452A (HH) recombinant BAC DNA. Total protein was harvested at 72 h posttransfection. Western blot analysis was performed by cutting the membrane to separate IE86 from IE72, using antibodies to detect viral MIE proteins and cellular β-tubulin. Mock samples contained pp71 but not BAC DNA.

Transactivation of early viral promoters.

The ability of the IE86 protein to transactivate early viral promoters and the absolute requirement for the protein in viral replication has been well documented. Therefore, we hypothesized that the lack of DNA replication from the BAC containing the P535A/Y537A mutant IE86 protein was due to a failure to transactivate early viral genes, including those that are involved in viral DNA replication. To test this hypothesis, we used a combination of early viral promoters driving a reporter gene and several endogenous early viral genes to examine the transactivation function of the mutant IE86 protein.

Expression from the modified early UL127 promoter driving the CAT reporter has been used as a preliminary indicator of the functional status of IE86 (34, 38). To determine if P535A/Y537A mutant IE86 can transactivate an early viral promoter, HFF cells were transfected with a plasmid containing the insert shown in Fig. 2A, consisting of the UL127-CAT reporter, a WT or mutant IE2 gene, and a β-Gal expression vector. CAT activity was analyzed after 72 h and normalized to protein and β-Gal input. WT IE86 activated the UL127-CAT promoter more than 10-fold compared to the mock control (Fig. 5A). L534A and Rev-PY IE86 also activated the early viral promoter to similar levels as WT IE86. The P535A/Y537A and H446A/H452A mutant IE86 proteins were unable to activate this reporter to WT levels, possibly explaining the failure of these mutants to replicate in the context of the recombinant BAC.

FIG. 5.

P535A/Y537A mutant IE86 protein is unable to transactivate early viral genes. (A) HFF cells were transfected, in triplicate, with β-Gal expression vector DNA and shuttle vector DNA containing WT, L534A, P535A/Y537A, revertant (Rev)-PY, or H446A/H452A IE2 and the modified UL127 early viral promoter driving the CAT reporter. Total protein was harvested at 72 h posttransfection. A CAT assay was performed to determine the ability of the IE86 protein to transactivate the early viral promoter, and a β-Gal assay was performed to determine transfection efficiency. Results are reported as CAT activity (percent acetylation per microgram protein, normalized to β-Gal). Mock samples contained β-Gal and the UL127-CAT reporter but not IE86. (B) HFF cells were transfected, in triplicate, with a viral pp71 expression vector and recombinant BACs encoding WT, P535A/Y537A, or H446A/H452A IE86. Total DNA was harvested at 24 h posttransfection; total RNA was harvested at 48 h (IE) and 72 h (early) posttransfection and converted to cDNA by reverse transcription. Real-time PCR was performed with primer/probe sets to detect HCMV gB DNA, HCMV MIE and TRS1 IE cDNA, HCMV UL44, UL54, and IRL7 early cDNA, and cellular 18S complementary rRNA genes. HCMV IE and early RNA transcription was measured based on the amount of HCMV cDNA, normalized to cellular 18S complementary rRNA genes and gB DNA input, relative to WT. Mock samples contained pp71 but not BAC DNA.

To confirm the early promoter-reporter results, we also analyzed the expression of several endogenous viral genes, including two that are directly involved in viral DNA replication. HFF cells were transfected with recombinant BACs encoding the WT or mutant IE86 protein. Expression of the IE (48 h) and early (72 h) genes was analyzed by real-time PCR and normalized to DNA input (24 h). P535A/Y537A and H446/H452A mutant IE86 failed to express the early genes that were tested, although both expressed similar levels of the IE gene TRS1 as WT IE86 (Fig. 5B). L534A and Rev-PY IE86 transactivate the early viral genes similar to WT, and no expression of early genes could be detected from samples lacking reverse transcriptase (data not shown). The lack of early gene expression, including that of genes involved in viral DNA replication, by the P535A/Y537A mutant IE86 protein is consistent with the failure of a recombinant BAC containing this mutation to replicate in HFF cells.

Recruitment of IE86 to the MIE promoter.

We have previously reported that WT IE86 binds to the wild type crs and mutation of the histidines at residues 446 and 452 prevents binding. In addition, WT IE86 does not bind to a mutated crs (39). Towne BAC with a mutated crs could not be isolated as infectious virus (H. Isomura and M. F. Stinski, unpublished data). Although we have already demonstrated at the RNA and protein levels that the P535A/Y537A mutant IE86 protein is able to negatively autoregulate expression from the MIE promoter, we wanted to confirm that the mutant protein was capable of being recruited to the promoter. Traditionally, a gel electromobility shift assay would be utilized for this task. However, due to the artificial nature of this assay and the ease with which results can be manipulated through buffer conditions, we selected the ChIP assay over a gel electromobility shift assay. Initially, nonpermissive 293 cells were utilized for this experiment because no recombinant virus was available from the nonreplicating IE86 mutants. However, all ChIP assays were also done in permissive HFF cells using the nucleofection method from Amaxa Biosystems as described in Materials and Methods.

To demonstrate that the IE86 protein was functional in 293 cells, a reporter construct consisting of the CAT gene under the control of the MIE promoter, including the autoregulatory MIE crs, was transfected into 293 cells with either WT or the mutant IE86 plasmids and a β-Gal expression vector. All mutant IE86 proteins were expressed at equivalent levels except H446A/H452A, which was expressed at approximately a threefold-higher level because of a failure to negatively autoregulate, as shown in Fig. 4B. After 48 h, a CAT assay was performed and normalized to β-Gal and protein input. WT IE86 was able to repress CAT expression more than 80% compared to the mock control (Fig. 6A). L534A, P535A/Y537A, and Rev-PY IE86 repressed CAT expression to similar levels, consistent with our results that these mutant IE86 proteins are able to autoregulate expression from the MIE promoter. In contrast, CAT activity in 293 cells transfected with the H446A/H452A mutant IE86 was more than threefold higher than WT IE86, indicating a defect in the ability to repress the MIE promoter.

FIG. 6.

P535A/Y537A mutant IE86 protein represses and is recruited to the MIE promoter in 293 and HFF cells. (A) 293 cells were transfected, in triplicate, with a β-Gal expression vector, a reporter construct consisting of the CAT gene under the control of the MIE promoter, including the autoregulatory MIE crs, and shuttle vector DNA encoding WT, L534A, P535A/Y537A, revertant (Rev)-PY, or H446A/H452A IE86. Total protein was harvested at 48 h posttransfection. A CAT assay was performed to determine the ability of the IE86 protein to repress the MIE promoter, and a β-Gal assay was performed to determine transfection efficiency. Results are reported as MIE-CAT activity (percent acetylation per microgram protein, normalized to β-Gal) relative to WT. Mock samples contained β-Gal and the MIE-CAT reporter but not IE86. (B) Western blot of ChIP lysates to detect equal expression of viral proteins (IE72) and to demonstrate the ability of the IP antibody to interact with the mutant proteins (IE86). An antibody specific to exon 4 (p63-27) demonstrates equal expression of IE72 in WT, L534A, P535A/Y537A (PY), and Rev-PY mutants, while the H446A/H452A (HH) mutant expresses higher levels of IE72 since it is unable to autoregulate the MIE promoter. An antibody specific to exon 5 (polyclonal 6655), which was used for IP, is able to detect phosphorylated (IE86p) and unphosphorylated IE86 in all mutants, in addition to a nonspecific (ns) protein that also appears in untransfected cells (mock). (C) HFF (shown) and 293 cells (not shown) were transfected with a plasmid containing the entire MIE locus, including the MIE crs and the WT or mutant IE2 gene. Cells were cross-linked with formaldehyde at 48 h posttransfection and ly- sed, and DNA/protein complexes were isolated. A ChIP assay was performed using polyclonal antibodies to immunoprecipitate (IP) HCMV IE86 or cellular TBP, or normal rabbit serum as a negative IP control, and nested PCR was performed to amplify the MIE promoter containing the MIE crs and TATA box. Purified PCR products were separated on an agarose gel. A positive (+) PCR control was performed using the crs-containing plasmid directly for nested PCR, while a negative (−) PCR control was performed without DNA template. The efficiency of the IP was compared using 10% of the input DNA from transfected cells, isolated directly from the lysed cells and not immunoprecipitated, for nested PCR. The specificity of the IP was compared using WT IE86-transfected cells, but immunoprecipitated using normal rabbit serum, for nested PCR.

To verify that the P535A/Y537A mutant IE86 is recruited to the MIE promoter, HFF and 293 cells were transfected with a plasmid containing the entire MIE locus, including the IE2 gene and the MIE crs. After 48 h, a ChIP assay was performed using polyclonal antibodies to either IE86 or cellular TBP or normal rabbit serum as a negative IP control. We selected polyclonal antibody 6655 for the ChIP analysis because it reacts with WT and all IE86 mutant proteins used (Fig. 6B) and has the advantage of interacting with multiple epitopes in case one or more of the epitopes are blocked by chromatin. Nested PCR was performed to amplify the MIE promoter, containing the MIE crs and TATA box, because single-step PCR gave weak and nondistinct bands. WT IE86 was recruited to the MIE promoter in HFF cells, presumably through direct binding to the MIE crs, and this interaction did not occur in the absence of IE86 or when using normal rabbit serum (Fig. 6C). L534A, P535A/Y537A, and Rev-PY IE86 were also recruited to the MIE promoter, consistent with their ability to repress the MIE promoter in 293 cells. In contrast, H446A/H452A mutant IE86 was not recruited to the MIE promoter. TBP was recruited to the MIE promoter in the presence or absence of IE86, regardless of whether the IE86 protein was WT or mutant, presumably through direct interaction with the TATA box. Similar results were obtained with 293 cells (data not shown). These data suggest that the failure of H446A/H452A mutant IE86 to autoregulate the MIE promoter is due to a defect in DNA binding.

Recruitment of IE86 to early viral promoters.

Using the ChIP system described above, we next attempted to determine if the P535A/Y537A mutant IE86 protein is recruited to early viral promoters. The results of this experiment could provide some insight into the reason for the failure of this mutant protein to transactivate early viral promoters. If the mutant IE86 protein was recruited to, but did not activate, the early viral promoter, it could be concluded that there is a defect in interaction with cellular transcription machinery. Alternatively, if the mutant IE86 protein was neither recruited to nor activated the early viral promoter, a defect in either direct DNA binding or in interaction with cellular transcription machinery could be involved. Two unique promoters were chosen for this experiment, based on a distinctive feature within the promoters. Both the UL4 and UL112 early viral promoters have been previously shown to contain a crs-like sequence that may facilitate direct binding of IE86 to the promoter (3, 8, 26, 51, 52).

To demonstrate that the early viral UL4 and UL112 promoters were functional, a reporter construct consisting of the CAT gene under the control of the UL4 or UL112 promoter was transfected into 293 cells with either WT or the mutant IE86 proteins. WT IE86 and mutant IE86 proteins were expressed at equivalent amounts with the exception of H446A/H452A, as discussed earlier and as shown in Fig. 6B. After 48 h, a CAT assay was performed. WT IE86 was able to activate CAT expression to similar levels as a positive control (HFFs cells infected with recombinant HCMV containing a UL127-CAT reporter), relative to the mock control (Fig. 7A). However, P535A/Y537A and H446A/H452A IE86 were unable to activate either the UL4 or UL112 promoters, consistent with our results that these mutant IE86 proteins are unable to transactivate early viral genes.

FIG. 7.

P535A/Y537A mutant IE86 protein fails to transactivate and is not recruited to early viral promoters in 293 and HFF cells. (A) 293 cells were transfected, in duplicate, with a reporter construct consisting of the CAT gene under the control of the early UL4 or UL112 promoters and shuttle vector DNA encoding WT, P535A/Y537A, or H446A/H452A IE86. Total protein was harvested at 48 h posttransfection, and a CAT assay was performed to determine the ability of the IE86 protein to transactivate the UL4 and UL112 promoters. Results are reported as CAT activity (percent acetylation per microgram protein) relative to mock. Mock samples contained the UL4-CAT or UL112-CAT reporter, but not IE86. The positive control (Pos) consisted of HFF cells infected with recombinant HCMV containing a UL127-CAT reporter. The negative control (Neg) consisted of mock-infected HFF cells. (B) HFF (shown) and 293 cells (not shown) were transfected with a plasmid containing the UL4 promoter, and (C) HFF (not shown) and 293 (shown) cells were transfected with a plasmid containing the UL112 promoter. The cells were also transfected with a plasmid containing the WT or mutant IE2 gene. Cells were cross-linked with formaldehyde at 48 h posttransfection and lysed, and DNA/protein complexes were isolated. A ChIP assay was performed using polyclonal antibodies to immunoprecipitate (IP) HCMV IE86 or cellular TBP, or normal rabbit serum as a negative IP control, and nested PCR was performed to amplify the UL4 (B) or UL112 (C) promoter. Purified PCR products were separated on an agarose gel. A positive (+) PCR control was performed using the promoter-containing plasmid directly for nested PCR, while a negative (−) PCR control was performed without DNA template. The efficiency of the IP was compared using 10% of the input DNA from transfected cells, isolated directly from the lysed cells and not immunoprecipitated, for nested PCR. The specificity of the IP was compared using WT IE86-transfected cells, but immunoprecipitated using normal rabbit serum, for nested PCR.

To test whether the P535A/Y537A mutant IE86 is recruited to the UL4 or UL112 promoters, HFF and 293 cells were transfected with plasmids containing the UL4 or UL112 promoters and WT or mutant IE86. After 48 h, a ChIP assay was performed using polyclonal antibodies to either IE86 or TBP, or using normal rabbit serum as a negative IP control, and nested PCR was performed to amplify the UL4 or UL112 promoters. Single-step PCR was not sufficient to detect the immunoprecipitated DNA. WT IE86 was recruited to both the UL4 (shown in HFF cells) and UL112 (shown in 293 cells) promoters, and this interaction was not present in the absence of IE86 or when using normal rabbit serum (Fig. 7B and C). L534A and Rev-PY IE86 were also recruited to the UL4 and UL112 promoters, consistent with their ability to transactivate early viral genes. In contrast, P535A/Y537A and H446A/H452A mutant IE86 were not recruited to these promoters. TBP was recruited to these viral promoters in the presence or absence of IE86, regardless of whether the IE86 protein was WT or mutant, presumably through direct interaction with the TATA box. Similar results were obtained for the UL4 promoter in 293 cells and for the UL112 promoter in HFF cells (data not shown). These data suggest that the failure of P535A/Y537A and H446A/H452A mutant IE86 proteins to transactivate early viral promoters is due to a lack of recruitment to these promoters.

DISCUSSION

In a viral genome of ∼240 kbp and over 150 ORFs (14), it is somewhat surprising that changing two amino acids in a single viral protein could result in complete elimination of viral replication. Despite the improbability of such a mutation, we were able to construct two recombinant HCMV BACs with double mutations in the IE2 gene that prevented the production of recombinant virus. The first, with mutations at amino acids P535 and Y537 of the IE86 protein, was able to autoregulate the MIE promoter but was not able to produce infectious virus because of a defect in transactivation of early viral promoters. The second, with mutations at amino acids H446 and H452 of the IE86 protein, was not able to produce infectious virus because of defects in both autoregulation and transactivation functions. Although replication deficient, these recombinant BACs became valuable resources in our studies of the “core” region of the IE86 protein and will provide future insight into the mechanisms of the multiple functions of IE86.

A third recombinant BAC, containing a conservative mutation at amino acid L534 of the IE86 protein, was able to produce infectious virus and retained all tested functions of IE86, in spite of the mutation in the “core” region. The L534A mutant replicated BAC DNA at 70% the level of WT (Fig. 3) and transactivated the UL127-CAT reporter at 69% the level of WT (Fig. 5A), but the L534A mutant replicated like WT otherwise. This variation could be inherent in the construction of recombinant BACs. Alternatively, there could be a slight perturbation in the structure of the mutant protein due to the minor alteration in the conserved 534LPIYE538 sequence, though the L534A mutant IE86 protein was recruited to the MIE and early viral promoters, in both HFF and 293 cells, and was immunoprecipitated by the anti-IE86 antibody. Structural alterations may also explain the more severe defects in the P535A/Y537A and H446A/H452A IE86 mutations. This would not be shocking, since these residues are so highly conserved between the HCMV IE86 homologs. However, the P535A/Y537A mutant IE86 protein is still capable of autoregulation, is recruited to the MIE promoter in both HFF and 293 cells, and is immunoprecipitated by the anti-IE86 antibody, and so defects other than gross protein misfolding must be responsible for the phenotype.

If not protein misfolding, then the mutations to the conserved sequence in the core domain must disrupt functional interactions of the IE86 protein. These interactions could include homodimerization, DNA binding, or interaction with cellular transcription machinery. Homodimerization of the mutant IE86 proteins was not tested. However, homodimerization is thought to be required for binding to the MIEP crs, as a mutant IE86 protein that was unable to form homodimers was not able to bind to a crs in a gel shift assay (40). Therefore, autoregulation of the MIE promoter by the P535A/Y537A mutant IE86 protein suggests that the homodimerization status of the mutant protein is normal. The recruitment of the P535A/Y537A mutant IE86 protein to the MIE promoter suggests that the DNA binding status of the mutant protein is also normal. The P535A/Y537A mutant IE86 protein is not recruited to the UL4 or UL112 promoters in HFF or 293 cells, despite the presence of a crs-like sequence in these promoters. This suggests that either the IE86 protein contains two independent DNA binding domains, which has not been previously reported in the literature, or that the IE86 protein is recruited to early viral promoters through protein-protein interactions.

TBP has been reported to interact with IE86 in vitro (7). In our ChIP assay, TBP was recruited to the UL4 and UL112 promoters in both HFF and 293 cells, regardless of whether IE86 was WT or mutant, and even in the absence of IE86 (Fig. 6B and 7B). This interaction of TBP and the early viral promoters presumably occurs through direct interaction with the TATA box. If IE86 did indeed interact with TBP in vivo, then it would be expected that a mutant IE86 protein that is defective in DNA binding would still be indirectly recruited to a promoter through TBP. However, neither the P535A/Y537A nor the H446A/H452A mutant IE86 protein is recruited to the UL4 or UL112 promoters. This suggests that the failure of these mutant proteins to transactivate or be recruited to early viral promoters may be related to a defect in protein-protein interactions. We are currently addressing this issue, in vivo, of whether the mutant IE86 proteins interact with TBP or other cellular transcription machinery.

The paradox of the HCMV IE86 protein is its ability to have opposite effects on different viral promoters. IE86 represses the viral MIE promoter, while it activates early viral promoters, such as UL44, UL54, and IRL7. Although this seems to be an unusual situation, it is not unique to HCMV. The herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) immediate-early protein ICP4 also possesses both positive and negative regulatory functions (16). Like HCMV IE86, HSV-1 ICP4 is required for viral replication (12, 13, 61). However, unlike IE86, there are still basal levels of transcription of HSV-1 early genes in the absence of ICP4. ICP4 interacts with the basal transcription machinery, including the TFIID complex which contains TBP, and recruits these factors to the viral promoters (19). In addition to protein interactions, a DNA binding domain in ICP4 is required for activation of early viral genes, although direct binding sites for ICP4 have not been detected in the promoters (27, 44, 47, 53, 54). Direct DNA binding is involved in ICP4-mediated repression of the IE promoters, and a binding site is present at the transcription initiation site (20, 45), similar to the HCMV MIE crs. Differential phosphorylation of ICP4 regulates the positive and negative regulatory functions (65, 66). These comparisons to ICP4 may be important for understanding the paradox of IE86 and the mechanisms of these contradictory functions.

The situation is further confused by the concept of a “core” domain, a region of the viral protein that is indispensable for all functions of the protein (4). It is evident that the carboxy terminus of IE86 is critical for the multiple functions of the protein. Interactions with TFIIB and TBP, dimerization and DNA binding, nuclear localization, and an activation domain have all been mapped to the carboxyl half of the viral protein. While this certainly suggests that the mechanisms for transactivation and autoregulation may overlap, it is naïve to believe that these opposing functions are so tightly linked that they cannot be separated. In fact, it has previously been shown that the transactivation, autoregulation, and DNA binding functions of HSV-1 ICP4 can be separated (11), and we have now shown the same with HCMV IE86. The core domain may simply be critical for IE86 structure, but not necessarily function, and major deletions or mutations in the core result in a misfolded protein.

In summary, we have constructed a recombinant HCMV BAC which contains two amino acid mutations in the core domain of the IE86 protein that is unable to replicate and fails to produce infectious virus. The mutations were targeted to disrupt a conserved LPIYE/D sequence in the CMV IE86 homologs. The P535A/Y537A mutant IE86 protein is unable to transactivate early viral genes and is not recruited to early viral promoters, resulting in a lack of viral DNA replication. However, unlike previous mutational analyses of the core domain, this mutant IE86 protein retains the ability to repress the MIE promoter and is recruited to the MIE promoter in vivo. Results were similar in both HFF and 293 cells, suggesting that the IE86 protein functions the same way in both cell types.

This finding is important for three reasons. First, the phenotype of this mutant demonstrates that mutations can be made in the core domain of the IE86 protein without disrupting all functions of the viral protein. Although the integrity of the core domain appears to be essential for the replication of HCMV, the functions of IE86 are not so tightly linked that they cannot be separated. Second, the separation of the autoregulatory and transactivating functions of the IE86 protein supports the belief that the viral protein must use two different mechanisms for promoter binding. Repression of the MIE promoter occurs through direct binding of the IE86 protein to the MIE crs, while transactivation of early viral promoters appears to occur through recruitment of the IE86 protein to the promoter via interactions with cellular transcription machinery but not direct DNA binding. Finally, this mutant protein provides a valuable tool to investigate the mechanisms of the paradoxical functions of the IE86 protein. Further studies with this mutant may reveal how a single viral protein is able to have opposite effects on different viral promoters.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Roller (University of Iowa) and members of the Stinski lab for critical reviews of the manuscript. We also acknowledge the University of Iowa DNA Facility for assistance with real-time PCR analysis.

This work was supported by grant AI-13562 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 21 March 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahn, J. H., C. J. Chiou, and G. S. Hayward. 1998. Evaluation and mapping of the DNA binding and oligomerization domains of the IE2 regulatory protein of human cytomegalovirus using yeast one and two hybrid interaction assays. Gene 210:25-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahn, J. H., Y. Xu, W. J. Jang, M. J. Matunis, and G. S. Hayward. 2001. Evaluation of interactions of human cytomegalovirus immediate-early IE2 regulatory protein with small ubiquitin-like modifiers and their conjugation enzyme Ubc9. J. Virol. 75:3859-3872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arlt, H., D. Lang, S. Gebert, and T. Stamminger. 1994. Identification of binding sites for the 86-kilodalton IE2 protein of human cytomegalovirus within an IE2-responsive viral early promoter. J. Virol. 68:4117-4125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asmar, J., L. Wiebusch, M. Truss, and C. Hagemeier. 2004. The putative zinc finger of the human cytomegalovirus IE2 86-kilodalton protein is dispensable for DNA binding and autorepression, thereby demarcating a concise core domain in the C terminus of the protein. J. Virol. 78:11853-11864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bresnahan, W. A., T. Albrecht, and E. A. Thompson. 1998. The cyclin E promoter is activated by human cytomegalovirus 86-kDa immediate early protein. J. Biol. Chem. 273:22075-22082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bresnahan, W. A., I. Boldogh, E. A. Thompson, and T. Albrecht. 1996. Human cytomegalovirus inhibits cellular DNA synthesis and arrests productively infected cells in late G1. Virology 224:150-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caswell, R., C. Hagemeier, C. J. Chiou, G. Hayward, T. Kouzarides, and J. Sinclair. 1993. The human cytomegalovirus 86K immediate early (IE) 2 protein requires the basic region of the TATA-box binding protein (TBP) for binding, and interacts with TBP and transcription factor TFIIB via regions of IE2 required for transcriptional regulation. J. Gen. Virol. 74:2691-2698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, J., and M. F. Stinski. 2000. Activation of transcription of the human cytomegalovirus early UL4 promoter by the Ets transcription factor binding element. J. Virol. 74:9845-9857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cherrington, J. M., E. L. Khoury, and E. S. Mocarski. 1991. Human cytomegalovirus ie2 negatively regulates α gene expression via a short target sequence near the transcription start site. J. Virol. 65:887-896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiou, C. J., J. Zong, I. Waheed, and G. S. Hayward. 1993. Identification and mapping of dimerization and DNA-binding domains in the C terminus of the IE2 regulatory protein of human cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 67:6201-6214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Compel, P., and N. A. DeLuca. 2003. Temperature-dependent conformational changes in herpes simplex virus ICP4 that affect transcription activation. J. Virol. 77:3257-3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeLuca, N. A., M. A. Courtney, and P. A. Schaffer. 1984. Temperature-sensitive mutants in herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP4 permissive for early gene expression. J. Virol. 52:767-776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dixon, R. A., and P. A. Schaffer. 1980. Fine-structure mapping and functional analysis of temperature-sensitive mutants in the gene encoding the herpes simplex virus type 1 immediate early protein VP175. J. Virol. 36:189-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunn, W., C. Chou, H. Li, R. Hai, D. Patterson, V. Stolc, H. Zhu, and F. Liu. 2003. Functional profiling of a human cytomegalovirus genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:14223-14228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellis, H. M., D. Yu, T. DiTizio, and D. L. Court. 2001. High efficiency mutagenesis, repair, and engineering of chromosomal DNA using single-stranded oligonucleotides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:6742-6746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Godowski, P. J., and D. M. Knipe. 1986. Transcriptional control of herpesvirus gene expression: gene functions required for positive and negative regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83:256-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graham, F. L., and A. J. van der Eb. 1973. A new technique for the assay of infectivity of human adenovirus 5 DNA. Virology 52:456-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greaves, R. F., and E. S. Mocarski. 1998. Defective growth correlates with reduced accumulation of a viral DNA replication protein after low-multiplicity infection by a human cytomegalovirus ie1 mutant. J. Virol. 72:366-379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grondin, B., and N. DeLuca. 2000. Herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP4 promotes transcription preinitiation complex formation by enhancing the binding of TFIID to DNA. J. Virol. 74:11504-11510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gu, B., R. Rivera-Gonzalez, C. A. Smith, and N. A. DeLuca. 1993. Herpes simplex virus infected cell polypeptide 4 preferentially represses Sp1-activated over basal transcription from its own promoter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:9528-9532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hagemeier, C., S. Walker, R. Caswell, T. Kouzarides, and J. Sinclair. 1992. The human cytomegalovirus 80-kilodalton but not the 72-kilodalton immediate-early protein transactivates heterologous promoters in a TATA box-dependent mechanism and interacts directly with TFIID. J. Virol. 66:4452-4456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hagemeier, C., S. M. Walker, P. J. Sissons, and J. H. Sinclair. 1992. The 72K IE1 and 80K IE2 proteins of human cytomegalovirus independently trans-activate the c-fos, c-myc and hsp70 promoters via basal promoter elements. J. Gen. Virol. 73:2385-2393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harel, N. Y., and J. C. Alwine. 1998. Phosphorylation of the human cytomegalovirus 86-kilodalton immediate-early protein IE2. J. Virol. 72:5481-5492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hermiston, T. W., C. L. Malone, and M. F. Stinski. 1990. Human cytomegalovirus immediate-early two protein region involved in negative regulation of the major immediate-early promoter. J. Virol. 64:3532-3536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hofmann, H., S. Floss, and T. Stamminger. 2000. Covalent modification of the transactivator protein IE2-p86 of human cytomegalovirus by conjugation to the ubiquitin-homologous proteins SUMO-1 and hSMT3b. J. Virol. 74:2510-2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang, L., and M. F. Stinski. 1995. Binding of cellular repressor protein or the IE2 protein to a cis-acting negative regulatory element upstream of a human cytomegalovirus early promoter. J. Virol. 69:7612-7621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Imbalzano, A. N., A. A. Shepard, and N. A. DeLuca. 1990. Functional relevance of specific interactions between herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP4 and sequences from the promoter-regulatory domain of the viral thymidine kinase gene. J. Virol. 64:2620-2631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Isomura, H., and M. F. Stinski. 2003. The human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early enhancer determines the efficiency of immediate-early gene transcription and viral replication in permissive cells at low multiplicity of infection. J. Virol. 77:3602-3614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Isomura, H., M. F. Stinski, A. Kudoh, T. Daikoku, N. Shirata, and T. Tsurumi. 2005. Two Sp1/Sp3 binding sites in the major immediate-early proximal enhancer of human cytomegalovirus have a significant role in viral replication. J. Virol. 79:9597-9607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Isomura, H., T. Tsurumi, and M. F. Stinski. 2004. Role of the proximal enhancer of the major immediate-early promoter in human cytomegalovirus replication. J. Virol. 78:12788-12799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jupp, R., S. Hoffmann, A. Depto, R. M. Stenberg, P. Ghazal, and J. A. Nelson. 1993. Direct interaction of the human cytomegalovirus IE86 protein with the cis repression signal does not preclude TBP from binding to the TATA box. J. Virol. 67:5595-5604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jupp, R., S. Hoffmann, R. M. Stenberg, J. A. Nelson, and P. Ghazal. 1993. Human cytomegalovirus IE86 protein interacts with promoter-bound TATA-binding protein via a specific region distinct from the autorepression domain. J. Virol. 67:7539-7546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lang, D., and T. Stamminger. 1993. The 86-kilodalton IE-2 protein of human cytomegalovirus is a sequence-specific DNA-binding protein that interacts directly with the negative autoregulatory response element located near the cap site of the IE-1/2 enhancer-promoter. J. Virol. 67:323-331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lashmit, P. E., C. A. Lundquist, J. L. Meier, and M. F. Stinski. 2004. Cellular repressor inhibits human cytomegalovirus transcription from the UL127 promoter. J. Virol. 78:5113-5123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee, G., J. Wu, P. Luu, P. Ghazal, and O. Flores. 1996. Inhibition of the association of RNA polymerase II with the preinitiation complex by a viral transcriptional repressor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:2570-2575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu, B., T. W. Hermiston, and M. F. Stinski. 1991. A cis-acting element in the major immediate-early (IE) promoter of human cytomegalovirus is required for negative regulation by IE2. J. Virol. 65:897-903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lukac, D. M., J. R. Manuppello, and J. C. Alwine. 1994. Transcriptional activation by the human cytomegalovirus immediate-early proteins: requirements for simple promoter structures and interactions with multiple components of the transcription complex. J. Virol. 68:5184-5193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lundquist, C. A., J. L. Meier, and M. F. Stinski. 1999. A strong negative transcriptional regulatory region between the human cytomegalovirus UL127 gene and the major immediate-early enhancer. J. Virol. 73:9039-9052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Macias, M. P., L. Huang, P. E. Lashmit, and M. F. Stinski. 1996. Cellular or viral protein binding to a cytomegalovirus promoter transcription initiation site: effects on transcription. J. Virol. 70:3628-3635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Macias, M. P., and M. F. Stinski. 1993. An in vitro system for human cytomegalovirus immediate early 2 protein (IE2)-mediated site-dependent repression of transcription and direct binding of IE2 to the major immediate early promoter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:707-711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malone, C. L., D. H. Vesole, and M. F. Stinski. 1990. Transactivation of a human cytomegalovirus early promoter by gene products from the immediate-early gene IE2 and augmentation by IE1: mutational analysis of the viral proteins. J. Virol. 64:1498-1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marchini, A., H. Liu, and H. Zhu. 2001. Human cytomegalovirus with IE-2 (UL122) deleted fails to express early lytic genes. J. Virol. 75:1870-1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meier, J. L., M. J. Keller, and J. J. McCoy. 2002. Requirement of multiple cis-acting elements in the human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early distal enhancer for viral gene expression and replication. J. Virol. 76:313-326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Michael, N., D. Spector, P. Mavromara-Nazos, T. M. Kristie, and B. Roizman. 1988. The DNA-binding properties of the major regulatory protein alpha 4 of herpes simplex viruses. Science 239:1531-1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Muller, M. T. 1987. Binding of the herpes simplex virus immediate-early gene product ICP4 to its own transcription start site. J. Virol. 61:858-865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murphy, E. A., D. N. Streblow, J. A. Nelson, and M. F. Stinski. 2000. The human cytomegalovirus IE86 protein can block cell cycle progression after inducing transition into the S phase of permissive cells. J. Virol. 74:7108-7118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paterson, T., and R. D. Everett. 1988. The regions of the herpes simplex virus type 1 immediate early protein Vmw175 required for site specific DNA binding closely correspond to those involved in transcriptional regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 16:11005-11025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Petrik, D. T., K. P. Schmitt, and M. F. Stinski. 2006. Inhibition of cellular DNA synthesis by the human cytomegalovirus IE86 protein is necessary for efficient virus replication. J. Virol. 80:3872-3883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pizzorno, M. C., and G. S. Hayward. 1990. The IE2 gene products of human cytomegalovirus specifically down-regulate expression from the major immediate-early promoter through a target sequence located near the cap site. J. Virol. 64:6154-6165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pizzorno, M. C., M. A. Mullen, Y. N. Chang, and G. S. Hayward. 1991. The functionally active IE2 immediate-early regulatory protein of human cytomegalovirus is an 80-kilodalton polypeptide that contains two distinct activator domains and a duplicated nuclear localization signal. J. Virol. 65:3839-3852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rodems, S. M., C. L. Clark, and D. H. Spector. 1998. Separate DNA elements containing ATF/CREB and IE86 binding sites differentially regulate the human cytomegalovirus UL112-113 promoter at early and late times in the infection. J. Virol. 72:2697-2707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schwartz, R., M. H. Sommer, A. Scully, and D. H. Spector. 1994. Site-specific binding of the human cytomegalovirus IE2 86-kilodalton protein to an early gene promoter. J. Virol. 68:5613-5622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shepard, A. A., A. N. Imbalzano, and N. A. DeLuca. 1989. Separation of primary structural components conferring autoregulation, transactivation, and DNA-binding properties to the herpes simplex virus transcriptional regulatory protein ICP4. J. Virol. 63:3714-3728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smiley, J. R., D. C. Johnson, L. I. Pizer, and R. D. Everett. 1992. The ICP4 binding sites in the herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein D (gD) promoter are not essential for efficient gD transcription during virus infection. J. Virol. 66:623-631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Song, Y. J., and M. F. Stinski. 2002. Effect of the human cytomegalovirus IE86 protein on expression of E2F-responsive genes: a DNA microarray analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:2836-2841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Song, Y. J., and M. F. Stinski. 2005. Inhibition of cell division by the human cytomegalovirus IE86 protein: role of the p53 pathway or cyclin-dependent kinase 1/cyclin B1. J. Virol. 79:2597-2603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stenberg, R. M., J. Fortney, S. W. Barlow, B. P. Magrane, J. A. Nelson, and P. Ghazal. 1990. Promoter-specific trans activation and repression by human cytomegalovirus immediate-early proteins involves common and unique protein domains. J. Virol. 64:1556-1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Taylor, R. T., and W. A. Bresnahan. 2005. Human cytomegalovirus immediate-early 2 gene expression blocks virus-induced beta interferon production. J. Virol. 79:3873-3877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Taylor, R. T., and W. A. Bresnahan. 2006. Human cytomegalovirus immediate-early 2 protein IE86 blocks virus-induced chemokine expression. J. Virol. 80:920-928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang, Y. C., C. F. Huang, S. F. Tung, and Y. S. Lin. 2000. Competition with TATA box-binding protein for binding to the TATA box implicated in human cytomegalovirus IE2-mediated transcriptional repression of cellular promoters. DNA Cell Biol. 19:613-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Watson, R. J., and J. B. Clements. 1978. Characterization of transcription-deficient temperature-sensitive mutants of herpes simplex virus type 1. Virology 91:364-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weinmann, A. S., S. M. Bartley, T. Zhang, M. Q. Zhang, and P. J. Farnham. 2001. Use of chromatin immunoprecipitation to clone novel E2F target promoters. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:6820-6832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wiebusch, L., and C. Hagemeier. 1999. Human cytomegalovirus 86-kilodalton IE2 protein blocks cell cycle progression in G1. J. Virol. 73:9274-9283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wu, J., R. Jupp, R. M. Stenberg, J. A. Nelson, and P. Ghazal. 1993. Site-specific inhibition of RNA polymerase II preinitiation complex assembly by human cytomegalovirus IE86 protein. J. Virol. 67:7547-7555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xia, K., N. A. DeLuca, and D. M. Knipe. 1996. Analysis of phosphorylation sites of herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP4. J. Virol. 70:1061-1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xia, K., D. M. Knipe, and N. A. DeLuca. 1996. Role of protein kinase A and the serine-rich region of herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP4 in viral replication. J. Virol. 70:1050-1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang, Z., D. L. Evers, J. F. McCarville, J. C. Dantonel, S. M. Huong, and E. S. Huang. 2006. Evidence that the human cytomegalovirus IE2-86 protein binds mdm2 and facilitates mdm2 degradation. J. Virol. 80:3833-3843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhu, H., J. P. Cong, G. Mamtora, T. Gingeras, and T. Shenk. 1998. Cellular gene expression altered by human cytomegalovirus: global monitoring with oligonucleotide arrays. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:14470-14775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhu, H., Y. Shen, and T. Shenk. 1995. Human cytomegalovirus IE1 and IE2 proteins block apoptosis. J. Virol. 69:7960-7970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]