Abstract

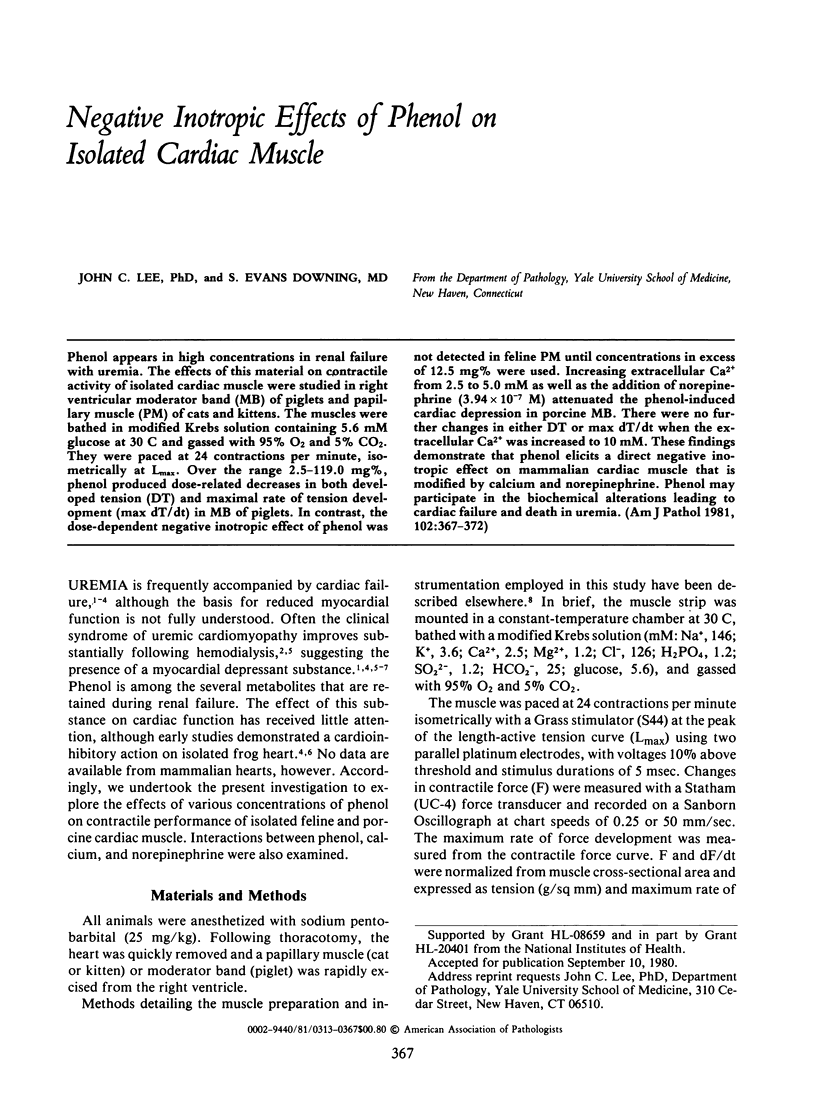

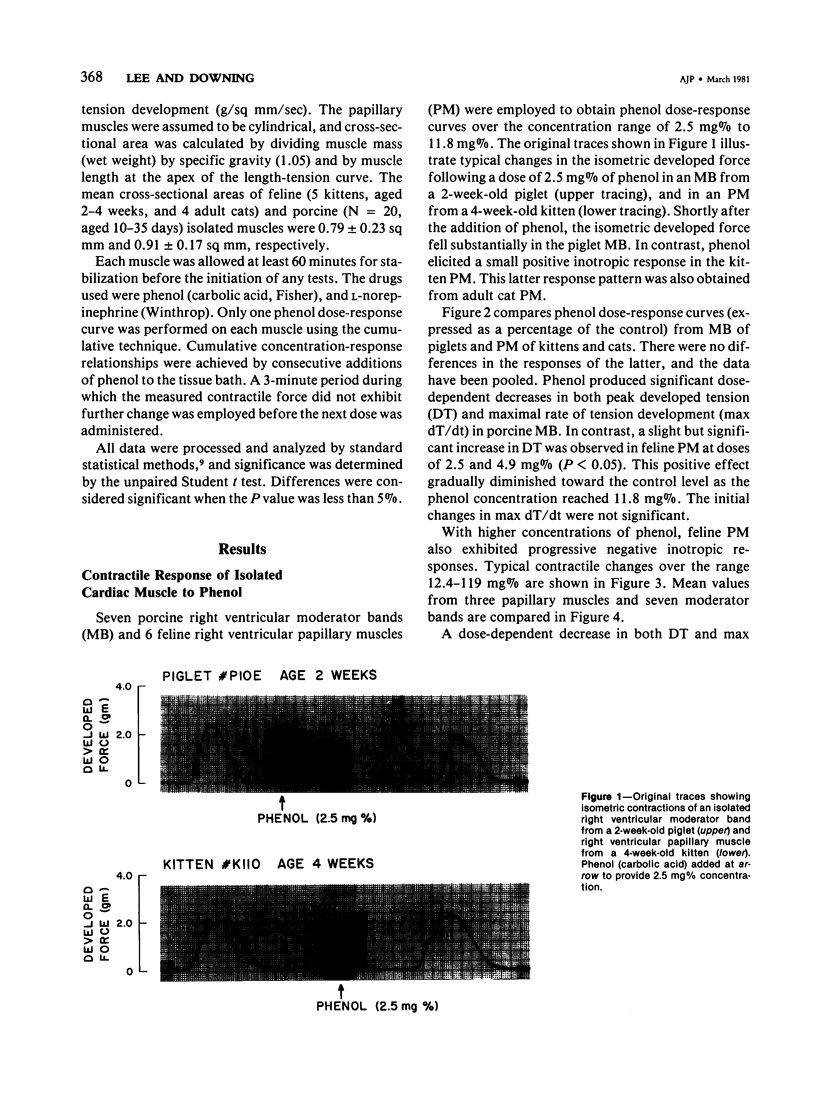

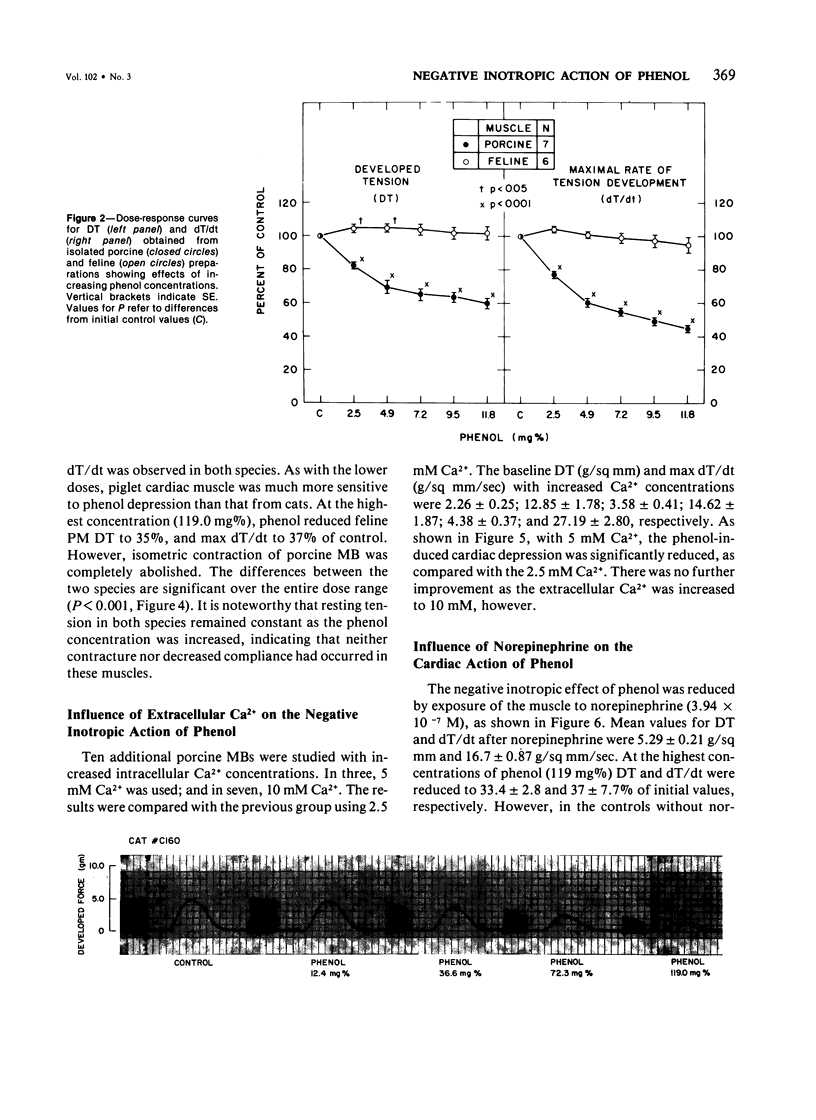

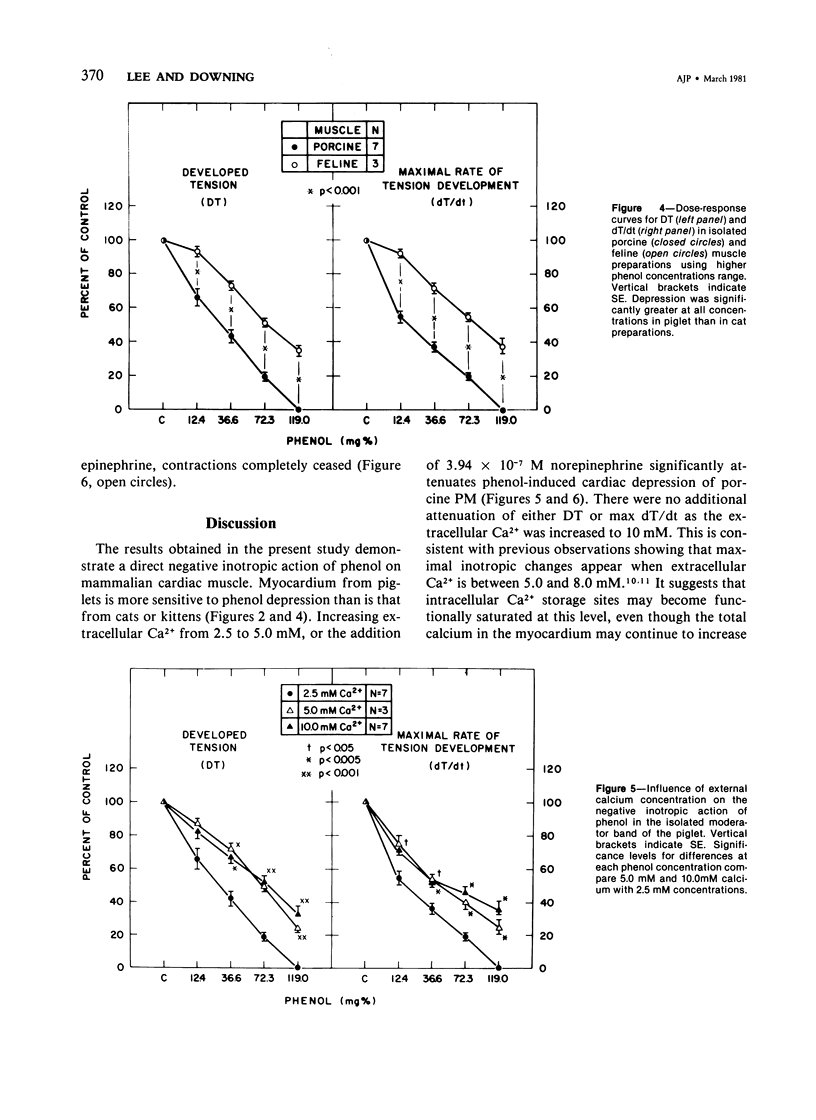

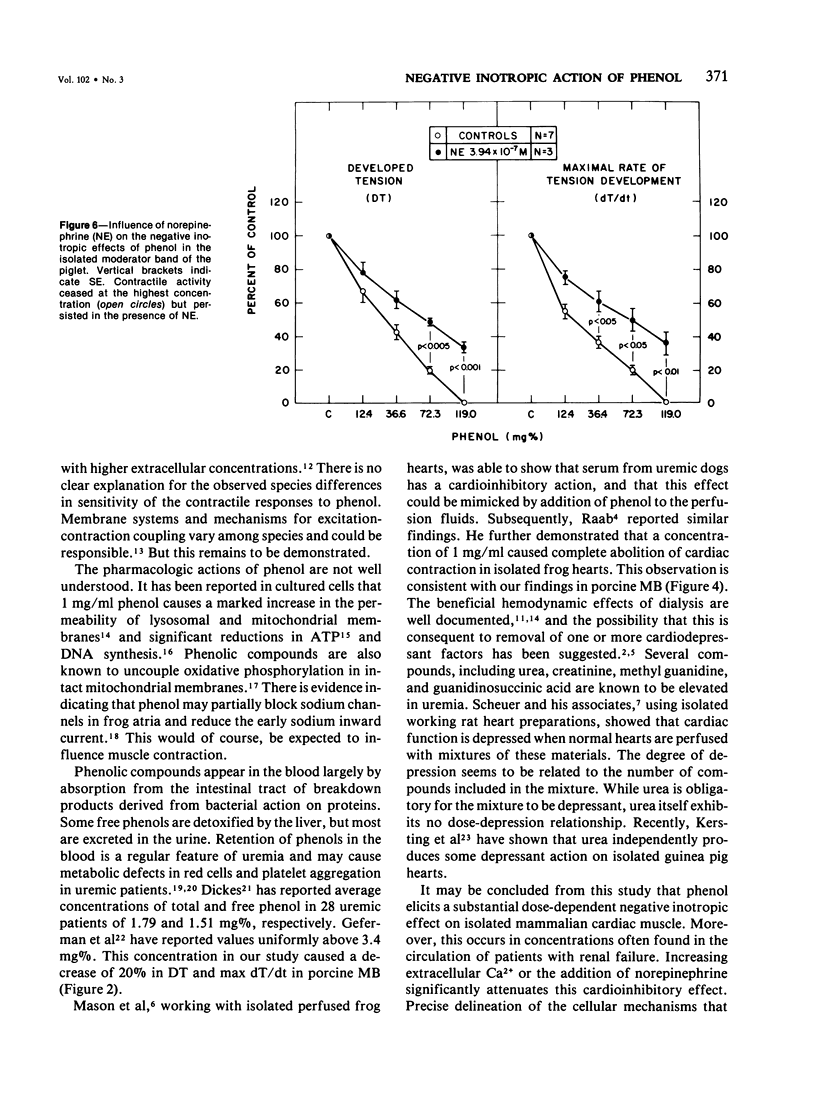

Phenol appears in high concentrations in renal failure with uremia. The effects of this material on contractile activity of isolated cardiac muscle were studied in right ventricular moderator band (MB) of piglets and papillary muscle (PM) of cats and kittens. The muscles were bathed in modified Krebs solution containing 5.6 mM glucose at 30 C and gassed with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. They were paced at 24 contractions per minute, isometrically at Lmax. Over the range 2.5-119.0 mg%, phenol produced dose-related decreases in both developed tension (DT) and maximal rate of tension development (max dT/dt) in MB of piglets. In contrast, the dose-dependent negative inotropic effect of phenol was not detected in feline PM until concentrations in excess of 12.5 mg% were used. Increasing extracellular Ca2+ from 2.5 to 5.0 mM as well as the addition of norepinephrine (3.94 x 10(-7) M) attenuated the phenol-induced cardiac depression in porcine MB. There were no further changes in either DT or max dT/dt when the extracellular Ca2+ was increased to 10 mM. These findings demonstrate that phenol elicits a direct negative inotropic effect on mammalian cardiac muscle that is modified by calcium and norepinephrine. Phenol may participate in the biochemical alterations leading to cardiac failure and death in uremia.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Del Greco F., Simon N. M., Roguska J., Walker C. Hemodynamic studies in chronic uremia. Circulation. 1969 Jul;40(1):87–95. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.40.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GABERMAN P., ATLAS D. H., ISAACS J., KAMMERLING E. M., EHRLICH L. The relationship of xanthoproteic indices to quantitative phenol levels in various azotemic states. J Lab Clin Med. 1951 Apr;37(4):544–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner T. H., Schanker L. S. Active transport of phenol red by rat lung slices. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1976 Feb;196(2):455–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersting F., Brass H., Heintz R. Uremic cardiomyopathy: studies on cardiac function in the guinea pig. Clin Nephrol. 1978 Sep;10(3):109–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer G. A. The intrinsic control of myocardial contraction--ionic factors. N Engl J Med. 1971 Nov 4;285(19):1065–1071. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197111042851910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. C., Downing S. E. Effects of insulin on cardiac muscle contraction and responsiveness to norepinephrine. Am J Physiol. 1976 May;230(5):1360–1365. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1976.230.5.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nivatpumin T., Yipintsoi T., Penpargkul S., Scheuer J. Increased cardiac contractility in acute uremia: interrelationships with hypertension. Am J Physiol. 1975 Aug;229(2):501–505. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1975.229.2.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabiner S. F., Molinas F. The role of phenol and phenolic acids on the thrombocytopathy and defective platelet aggregation of patients with renal failure. Am J Med. 1970 Sep;49(3):346–351. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(70)80026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuer J., Stezoski W. The effects of uremic compounds on cardiac function and metabolism. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1973 Jun;5(3):287–300. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(73)90068-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seraydarian M. W., Harary I., Sato E. In vitro studies of beating-heart cells in culture. XI. The ATP level and contractions of the heart cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1968 Oct 1;162(3):414–423. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(68)90127-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenblick E. H., Parmley W. W., Buccino R. A., Spann J. F., Jr Maximum force development in cardiac muscle. Nature. 1968 Sep 7;219(5158):1056–1058. doi: 10.1038/2191056a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trautwein W., McDonald T. F. Current-voltage relations in ventricular muscle preparations from different species. Pflugers Arch. 1978 Apr 25;374(1):79–89. doi: 10.1007/BF00585700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyas M. J. A histochemical study of the effect of phenol on the mitochondria and lysosomes of cultured cells. Histochem J. 1978 May;10(3):333–342. doi: 10.1007/BF01007563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueba Y., Ito Y., Chidsey C. A., 3rd Intracellular calcium and myocardial contractility. I. Influence of extracellular calcium. Am J Physiol. 1971 May;220(5):1553–1557. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1971.220.5.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEINBACH E. C., GARBUS J. THE INTERACTION OF UNCOUPLING PHENOLS WITH MITOCHONDRIA AND WITH MITOCHONDRIAL PROTEIN. J Biol Chem. 1965 Apr;240:1811–1819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle E. N. A study of the effects of possible toxic metabolites of uraemia on red cell metabolism. Acta Haematol. 1970;43(3):129–143. doi: 10.1159/000208723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wennberg A. An in vitro method for toxicity evaluation of water-soluble substances. Acta Odontol Scand. 1976;34(1):33–41. doi: 10.3109/00016357609026556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]