Abstract

An increasing number of girls are entering the juvenile justice system. However, intervention programs for delinquent girls have not been examined empirically. We examined the 12-month outcomes of a randomized intervention trial for girls with chronic delinquency (N = 81). Girls were randomly assigned into an experimental condition (Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care [MTFC]) or a control condition (group care [GC]). ANCOVAs indicated that MTFC youth had a significantly greater reduction in the number of days spent in locked settings and in caregiver-reported delinquency, and had 42% fewer criminal referrals than GC youth (a trend) at the 12-month follow-up. Implications for reducing girls' chronic delinquency are discussed.

Keywords: girl, delinquency, intervention, arrest, foster care

Intervention Outcomes for Girls Referred from Juvenile Justice: Effects on Delinquency

Girls under the age of 18 are the fastest growing segment of the U.S. juvenile justice population; their delinquency rates increased by 83% between 1988 and 1997 (American Bar Association and National Bar Association, 2001). Converging sources confirm that juvenile justice systems across the U.S. are faced with a rapidly growing population of serious female delinquents (Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 1999). Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have shown cascading negative outcomes for girls who engage in serious antisocial behavior, which set girls up for later poverty, use of publicly funded services, incarceration, and involvement in domestic violence (Leve & Chamberlain, 2004; Serbin et al., 2004). However, many community service providers have little experience treating delinquent girls. Furthermore, studies show that such girls tend not to make use of mental health, social service, or educational delivery systems as often as males with similar problems (Offord, Boyle, & Racine, 1991). Thus, the need for effective prevention and treatment approaches for girls in the juvenile justice system is clear.

Prior studies with males have shown that interventions designed to address multiple risk factors have shown positive outcomes (Chamberlain & Reid, 1998; Henggeler, Schoenwald, Rowland, & Cunningham, 2002). In addition, recent theoretical models and empirical advances have highlighted potential gender-related interpersonal dynamics (e.g., social or relational aggression) that inform relevant interventions for female adolescent offenders (Underwood, 2003). Based on this theoretical and intervention research base, we examined the efficacy of an adapted version of Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care (MTFC; Chamberlain, 2003), which was designed to target the proximal antecedents of delinquency, with a sample of 81 girls in the juvenile justice system.

MTFC was originally developed to provide a community-based alternative to incarceration for boys with serious and chronic delinquency. A randomized trial testing the efficacy of MTFC for boys found significantly lower rates of official and self-reported delinquency in MTFC boys than boys in the control condition (group care [GC]) in a 1-year follow-up and lower rates of violent offending in a 2-year follow-up (Chamberlain & Reid, 1998; Eddy, Whaley & Chamberlain, 2004). The current report was the first randomized study to test an intervention focused on girls with chronic delinquency. The study objective was to examine whether MTFC girls had lower delinquency rates than GC girls in a 12-month follow-up.

Method

Participants

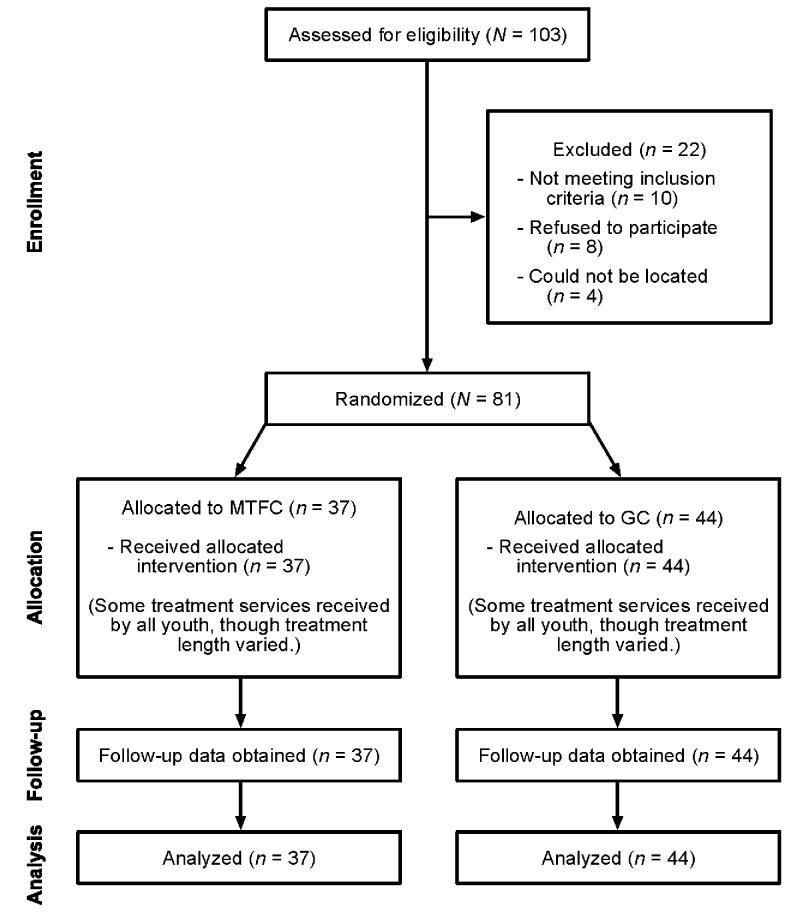

Juvenile court judges in Oregon referred 103 girls for enrollment in the study between 1997 and 2002; the girls had been mandated to community-based out-of-home care due to problems with chronic delinquency. The study enrolled all referred girls who were 13–17 years old, who had at least one criminal referral of any type in the prior 12 months, who were not currently pregnant, and who were placed in out-of-home care within 12 months following referral (N = 81). The flow of participants through each stage of the study is presented in Figure 1. The study's project manager randomly assigned eligible girls into the experimental condition (MTFC; n = 37) or the control condition (GC; n = 44). All youth and caregivers in both conditions were aware that they were participants in a research study and were aware that they were receiving treatment services. Analyses included the entire intent-to-treat randomized sample, although there was variability in the intervention dosage received in both groups. The mean length of stay in the randomized intervention placement was 174 days (SD = 144 days), and the average time between baseline and intervention entry was 47 days. Neither of these variables differed significantly by group.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of participants through each stage of the randomized trial.

The girls were 13–17 years old at baseline (M = 15.3; SD = 1.1); 74% were Caucasian, 2% were African-American, 9% were Hispanic, 12% were Native American, 1% were Asian, and 2% were other or of mixed ethnic heritage. In contrast, 93% of the girls aged 13–19 living in the region at the time of the study were Caucasian (U.S. Department of Commerce, 1992). At the baseline assessment, 68% of the girls had been residing in a single-parent family, and 32% of the girls lived in families with an income of less than $10,000. Prior to entering the study, the girls had a lifetime average of 11.9 criminal referrals each (SD = 8.9), and 70% of the girls had at least one prior felony. There were no group differences on the rates or types of prebaseline offenses or on other demographic characteristics. No adverse events occurred during the course of the study.

Procedure

Prior to entry into the designated out-of-home placement setting, each girl and her primary preplacement caregiver participated in a 2-hour baseline (BL) assessment. The BL caregiver was typically a biological parent (92% of the time). Upon exit from the intervention setting, girls were reunified with their biological or other aftercare family (56%), began living independently (23%), returned to detention settings for subsequent criminal offenses (15%), or remained in some type of treatment setting (6%). The staff members responsible for the data collection and data entry were blind to the group assignment of the participants and were not involved in the intervention delivery. Girls and their current caregiver completed a follow-up assessment (FU) at 12 months post-BL. Juvenile court records were collected for each girl.

Experimental Intervention

In the MTFC condition, girls were individually placed in highly trained and supervised foster homes with state-certified foster parents. Experienced program supervisors with small caseloads (10 MTFC families) supervised all clinical staff, coordinated all aspects of the youth's placement, and maintained daily contact with MTFC parents to provide ongoing consultation, support, and crisis intervention services and to monitor treatment fidelity. The intervention was individualized for each girl but included the following basic MTFC components: (a) daily (Monday–Friday) telephone contact with the foster parents using the Parent Daily Report Checklist (Chamberlain & Reid, 1987) to monitor case progress and foster parents adherence to the MTFC model; (b) weekly group supervision and support meetings for foster parents; (c) an individualized, in-home, daily point-and-level program for each girl; (d) individual therapy for each girl; (e) family therapy (for the family of origin) focusing on parent management strategies; (f) close monitoring of school attendance, performance, and homework completion; (g) case management to coordinate the interventions in the foster family, peer, and school settings; (h) program staff on call at all times for foster and biological parents; and (i) psychiatric consultation as needed.

To address gender-specific processes identified in previous research (Chamberlain & Reid, 1994; Underwood 2003), foster parents were trained to provide reinforcement (extra points) for girls' avoidance of social/relational aggression, and sanctions (loss of points) for girls' commission of social/relational aggression. Girls were taught strategies for avoiding social/relational aggression (e.g., practicing ways to talk directly to friends about distressing or uncomfortable situations) and for regulating their emotions (e.g., recognizing their feelings of distress, practicing coping strategies, and generating various solutions for dealing with problems).

Program supervisors monitored intervention fidelity using Parent Daily Report Checklist data about each girl's performance on the point-and-level system, the amount of unsupervised time, school attendance and performance, family and peer relationships, and foster parent stress level. They also viewed videotaped family and individual therapy sessions and supervised therapists and foster parents on a daily basis (Monday–Friday) to correct fidelity issues. A more complete description of the program can be found in Chamberlain (2003).

Control Condition

GC girls went to 1 of 19 community-based group care programs located throughout the state of Oregon. These programs represented typical services for girls being referred to out-of-home care by the juvenile justice system. The programs had 2–51 youth in residence (M = 21), 1–50 staff members (median = 2), and on-site schooling. Although the programs differed somewhat in their theoretical orientations, 86% of the programs reported that they endorsed a specific treatment model, of which the primary philosophy of their program was a behavioral (70%), eclectic (26%), or family-style therapeutic approach (4%). Seventy percent of the programs reported that they delivered therapeutic services at least weekly.

Measures

We operationalized delinquency as engagement in an activity or behavior that could result in arrest. The study contained four measures of delinquency.

Days in locked settings

At BL, caregivers and girls were asked where the girl was residing each day during the prior 12-month period using the Characteristics of Living Situations (Hawkins, Almeida, Fabry, & Reitz, 1992). At FU, this information was obtained from the girl only. Time spent in detention facilities, correctional facilities, jail, or prison was tallied to score the number of days in locked settings. We computed the number of days in locked settings in the 12 months before and after treatment entry. The means and standard deviations by group are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of Predictors and Outcomes

| MTFC |

GC |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | M | SD | M | SD |

| BL predictors | ||||

| Days in locked settings | 74.97 | 81.59 | 89.25 | 96.12 |

| Number of criminal referrals | 5.24 | 4.72 | 4.48 | 4.15 |

| CBCL delinquency | 79.74 | 10.60 | 78.79 | 8.66 |

| Elliott delinquency | 33.24 | 21.62 | 35.98 | 26.25 |

| FU outcomes | ||||

| Days in locked settings | 21.70 | 48.95 | 56.45 | 84.13 |

| Number of criminal referrals | .76 | 1.14 | 1.30 | 1.67 |

| CBCL delinquency | 64.75 | 9.11 | 70.03 | 11.13 |

| Elliott delinquency | 18.85 | 19.37 | 15.13 | 18.88 |

Note. CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist.

Criminal referrals

The number of criminal referrals in the 12 months before and after treatment entry was collected using state police records and circuit court data. The court records contain a list of the individual charges for each girl and the disposition of each charge. Court records have been found to be reliable indicators of externalizing behavior (Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999).

Caregiver-reported delinquency

The girls' current caregiver completed the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991) at the BL and FU assessments. The delinquency subscale was used (13 items assessing behaviors such as stealing, truancy, and fire setting). Reliability was acceptable (BL α = .85; FU α = .86).

Self-reported delinquency

Girls completed the Elliott Self-Report of Delinquency Scale (Elliott, Huizinga, & Ageton, 1985) at the BL and FU assessments. The 21-item general delinquency subscale was used, which records the number of times girls reported violating certain laws during the preceding 12 months. Each item was capped at a maximum frequency prior to computing the total score. This strategy was used in samples of male juvenile offenders to transform the scores closer to normality (Chamberlain & Reid, 1998; Eddy & Chamberlain, 2000). Internal consistency of the subscale was acceptable (BL α = .83; FU α = .84).

Results

As indicated in Table 1, there were no significant mean-level differences on the BL delinquency measures by group (as was anticipated given random assignment). The means on the delinquency outcome variables suggested that, compared to GC girls, MTFC girls spent fewer FU days in locked settings, had fewer criminal referrals, and had fewer delinquent behaviors as rated by their caregiver on the CBCL. To examine the statistical significance of the FU measures while controlling for initial status, we conducted four ANCOVAs with the BL variable as a covariate and group condition as a predictor (1 = MTFC; 0 = GC). The Group X BL variable interaction term was nonsignificant in each model and was thus removed. The four FU delinquency measures served as the dependent variables.

The ANCOVA for the number of days in locked settings indicated a significant effect for group condition, F(1, 76) = 4.25, p < .05, with the MTFC girls having significantly fewer FU days in locked settings than the GC girls. The days in locked settings ANCOVA also indicated a significant effect of BL days in locked settings, F(1, 76) = 11.35, p < .01, with more BL days in locked settings predicting more FU days in locked settings. The overall model tests and effect sizes are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

ANCOVA Models for the Four Delinquency Outcomes

| Effect of predictors (η2) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Overall model | BL | Group |

| Days in locked settings | F(2, 76) = 8.43, p < .001 | .13** | .05* |

| Number of criminal referrals | F(2, 78) = 1.39, p = ns | .00 | .03† |

| CBCL delinquency | F(2, 55) = 3.28, p < .05 | .03 | .07* |

| Elliott delinquency | F(2, 69) = 1.14, p = ns | .02 | .01 |

Note. CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

The ANCOVA for the number of criminal referrals indicated a trend for group condition, F(1, 78) = 2.78, p = .10, with MTFC girls showing fewer FU criminal referrals than GC girls. The ANCOVA for CBCL delinquency indicated a significant effect of group condition, F(1, 55) = 4.06, p < .05, with MTFC girls having significantly lower FU delinquency T-scores than GC girls. The ANCOVA for Elliott delinquency did not indicate a significant effect for group condition or for BL Elliott scores.

Discussion

The focus of this study was to develop and to test a research-based intervention to reduce incarceration and delinquency for girls with chronic delinquency. The results of this randomized trial suggest that the MTFC intervention was more effective than the control condition in reducing incarceration and delinquency rates. The MTFC girls had spent 53 fewer days in locked settings at FU than they had in the 12 months preceding treatment. This resulted in a significant group difference, with MTFC girls having spent 62% fewer days in locked settings at FU than GC girls. Criminal referral rates showed a group trend, with MTFC girls' referral rates decreasing 85%, a 42% greater reduction in criminal referrals compared to the GC girls. These group differences extended to caregiver-reported delinquency: MTFC girls' FU delinquency T-scores fell in the subclinical range (less than 67), whereas GC girls' FU delinquency T-scores remained in the clinical range (70 or greater). Taken together, these results suggest that MTFC is more effective than group care in reducing delinquency in girls referred for out-of-home care.

Our results also suggest some inconsistency in the effectiveness of MTFC: Group effects were not found for self-reported delinquency, though rates dropped by about 50% between BL and FU for girls in both groups. However, at least six girls self-reported 0–4 delinquent acts at FU even though their official criminal records at FU indicated higher numbers. Given that official criminal referrals are generally considered to underestimate the volume of serious delinquency because police detect only a fraction of delinquent acts, our findings suggest that a number of girls underreported their delinquent activity, a potential reporting biases needing examination in future studies.

The interventions compared in this study differed in theoretical and structural ways. Whereas MTFC stresses one-to-one adult mentoring with girls living in a family setting away from delinquent peers, group care programs stress peer-focused interventions using shift staff in aggregate care settings. Although the results reported here are promising, research that specifies how the daily experiences of girls in these two program models differ and how these differences relate to longer term outcomes could improve the precision and the effectiveness of future interventions for chronically delinquent girls. In addition, samples that include greater diversity in ethnicity are needed to examine the efficacy of MTFC in non-Caucasian ethnic groups. Given the high levels of co-occurring mental health problems for delinquent girls, an examination of the effectiveness of interventions to reduce mood disorders in delinquent girls is also warranted. Thus, the current study represents a modest first step in developing effective interventions for girls in the juvenile justice system, though additional steps are needed to tailor and improve such interventions. By utilizing the expanding research base on the developmental antecedents and mediators of antisocial behavior in girls in the development of new interventions, it is likely that significant progress could be made in the development of interventions for delinquent girls. Additionally, and perhaps more importantly in the long run, rigorous randomized trials such as the one reported here can serve as experimental tests that further improve developmental theory.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank David DeGarmo for statistical consultation; JP Davis and Dana Smith for implementing the intervention; Courtenay Paulic, Alice Wheeler, and Sara Webb for data collection/management; the Oregon Youth Authority directors (Rick Hill, Karen Brazeau, and Robert Jester) and the Lane County Department of Youth Services for their assistance and support; Matthew Rabel for editorial assistance; and all the youth, parents, and foster parents who volunteered to participate in this research study.

Footnotes

Support for this research was provided by the Oregon Youth Authority and by the following grants: DA15208, NIDA, U.S. PHS; MH54257, NIMH, U.S. PHS; and MH46690, NIMH, U.S. PHS.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 profile. University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; Burlington, VT: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- American Bar Association and National Bar Association . Justice by gender: The lack of appropriate prevention, diversion and treatment alternatives for girls in the justice system. Authors; Washington, DC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Stoolmiller M. Co-occurrence of conduct problems and depressive symptoms in early adolescent boys: III. Prediction to young-adult adjustment. Development & Psychopathology. 1999;11:59–84. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499001959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P. Treating chronic juvenile offenders: Advances made through the Oregon MTFC model. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Reid JB. Differences in risk factors and adjustment for male and female delinquents in Treatment Foster Care. Journal of Child & Family Studies. 1994;3:23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Reid JB. Comparison of two community alternatives to incarceration for chronic juvenile offenders. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:624–633. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy JM, Chamberlain P. Family management and deviant peer association as mediators of the impact of treatment condition on youth antisocial behavior. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:857–863. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.5.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy JM, Whaley RB, Chamberlain P. The prevention of violent behavior by chronic and serious male juvenile offenders: A 2-year follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Emotional & Behavioral Disorders. 2004;12:2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Huizinga D, Ageton SS. Explaining delinquency and drug use. Sage; Beverly Hills, CA: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Bureau of Investigation . Crime in the United States 2000. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins RP, Almeida MC, Fabry B, Reitz AL. A scale to measure restrictiveness of living environments for troubled children and youths. Hospital & Community Psychiatry. 1992;23:54–58. doi: 10.1176/ps.43.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Schoenwald SK, Rowland MD, Cunningham PB. Serious emotional disturbance in children and adolescents: Multisystemic therapy. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Chamberlain P. Female juvenile offenders: Defining an early-onset pathway for delinquency. Journal of Child & Family Studies. 2004;13:439–452. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention . Juvenile offenders in residential placement. Vol. 1997. Author; Washington, DC: 1999. Fact Sheet #96. [Google Scholar]

- Offord DR, Boyle MH, Racine YA. The epidemiology of antisocial behavior in childhood and adolescence. In: Pepler DJ, Rubin KH, editors. The development and treatment of childhood aggression. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1991. pp. 31–54. [Google Scholar]

- Serbin LA, Stack DM, De Genna N, Grunzeweig N, Temcheff CE, Schwartzman AE, et al. When aggressive girls become mothers: Problems in parenting, health, and development across two generations. In: Putallaz M, Bierman KL, editors. Aggression, antisocial behavior, and violence among girls. Guilford Press; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood MK. Social aggression among girls. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Commerce . 1990 census of population: General population characteristics, Oregon. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 1992. (USDC Publication No. 1990 CP-1-39). [Google Scholar]