Abstract

Autoimmune enteropathy (AIE) is a rare disorder characterized by intractable diarrhoea and anti-enterocyte autoantibody. In this study, we detected a 75-kD autoantigen which distributed through the whole intestine and the kidney, as assessed by Western blot analysis using sera from two unrelated cases of AIE associated with nephropathy. Our results suggest that the detection of the autoantibody against the 75-kD antigen has a diagnostic value in AIE and that the autoimmune reaction against the 75-kD antigen may be implicated in the development of intestinal and renal tissue damage in this rare disorder.

Keywords: autoimmune enteropathy, nephropathy, autoantigen, Western blot

INTRODUCTION

Autoimmune enteropathy (AIE) is a rare disorder defined by protracted diarrhoea and severe enteropathy, no response to exclusion diet or total parenteral nutrition, evidence of predisposition to autoimmune disease, and no severe immunodeficiency [1–3]. We have reported three Japanese cases of X-linked AIE, in one of which combination therapy with tacrolimus and corticosteroid was effective [4,5]. In previous reports, including ours [1–4,6–12], circulating autoantibodies reactive with intestinal tissue have been detected by immunohistology. However, the property of the target antigen(s) remains unclear. In the present study we identified in the normal small intestinal tissue a 75-kD antigen that was reactive with the sera from two unrelated Japanese patients with AIE using Western blot analysis. The search for the 75-kD antigen in various human tissues disclosed that it also distributed in the kidney.

Patient profiles

Case 1

Clinical and laboratory findings have been reported in detail previously [4,5]. Briefly, the patient, now a 6-year-old boy, had been diagnosed as having autoimmune thyroiditis at his birth and autoimmune haemolytic anaemia (AIHA) at the age of 2 months. At 5 months he developed intractable diarrhoea and was admitted to Hokkaido University Hospital. The diagnosis of AIE was made by the presence of autoantibody against normal jejunal tissues by immunohistological study which showed the staining of cytoplasm and brush border of enterocytes. Although haematuria was not detected, high levels of blood urea nitrogen (40 mg/dl) and serum creatinine (1 mg/dl) suggested renal damage. Particularly, high concentrations of urinary β2-microglobulin (β2-M; 5000–12 000 μg/l) suggested renal tubular damage. His elder brother and his maternal uncle had died of severe diarrhoea complicated with hypothyroidism or insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM) at their infancy, suggesting the syndrome had been inherited in an X-linked manner. His diarrhoea was successfully treated with the combination of tacrolimus and betamethasone.

Case 2

A 6-month-old boy was admitted to Ryukyu University Hospital because of intractable diarrhoea. Immunological studies at the age of 17 months showed high serum level of IgG (1477 mg/dl) and IgE (12 000 U/ml) with positive IgE radioallergosorbent test (RAST) for cow's milk. His diarrhoea was refractory to diet therapy with peptide formula or total parenteral nutrition. The diagnoses of IDDM and hypothyroidism were also made. In addition, high levels of his urinary β2-M (5000–35 000 μg/l) suggested renal tubular damage. Immunohistological studies using his serum showed a faint staining of intestinal brush border, suggesting the diagnosis of AIE. Circulating autoantibody was IgG class. His maternal uncle died of intractable diarrhoea, although further information was not available, suggesting X-linked inheritance of the disease. At the age of 3 years, he died of bacterial sepsis before the administration of immunosuppressive drugs. Autopsy findings showed villous atrophy and massive infiltration of mononuclear cells into the lamina propria of the whole intestine, in agreement with those observed in AIE. Interstitial nephritis was also diagnosed pathologically. In both cases, all of the criteria proposed by Unsworth & Walker-Smith were met [3].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissues and cells

Duodenal, jejunal and ileal tissues were obtained from patients with pancreas carcinoma undergoing surgical resection. Kidney and thyroid were obtained from patients with renal or thyroid cancer undergoing nephrectomy or thyroidectomy, respectively. Normal tissues adjacent to the tumour were used for samples. Liver was obtained from autopsy specimens from a patient with GM1-gangliosidosis. Peripheral blood was obtained from a healthy control and separated into mononucleocytes (PBMC) and erythrocytes by Ficoll–Paque gradient centrifugation.

Sample preparation and Western blot analysis

Tissues and cells were mechanically homogenized and sonicated in PBS pH 7.4, containing 1% Nonidet P-40 and 1 mm phenyl methyl sulphonyl fluoride (Sigma, St Louis, MO). After centrifugation, the supernatants were collected and protein concentrations were measured by DC Protein Assay (BioRad Labs, Hercules, CA). They were mixed with Laemmli's sample buffer [13] containing 1 mm dithiothreitol (Sigma) and boiled for 3 min. Five micrograms of each sample were electrophoresed on 7.5% SDS–PAGE, and were then electrically transferred onto nylon membranes (Atto, Tokyo, Japan). After blocking in 5% non-fat milk at 4°C for 16 h, membranes were incubated with 200-fold diluted sera from patients or controls at room temperature for 1 h. After washing three times with Tris-buffered saline pH 7.4 containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS–T), the membranes were incubated with 1500-fold diluted peroxidase (PO)-conjugated goat anti-human IgG (Tago, Burlingame, CA) at room temperature for 1 h. All sera and second antibodies were diluted with TBS–T. After washing three times with 50 mm Tris–HCl pH 7.4, the membrane was incubated with a peroxidase substrate, diaminobenzidine (Sigma), dissolved in 50 mm Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 0.03% hydrogen peroxide and 0.03% NiCl2.

Sera

Patients' sera were obtained from case 1 at the time of his admission, the first remission and the first relapse, and from case 2 at admission. Control sera were obtained from five normal volunteers, two patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), two with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA), two with ulcerative colitis (UC), two with Crohn's disease (CD) and one with Behçet's disease affecting small intestine, four with primary Sjögren's syndrome (pSS), three with dermatomyositis (DM), one with chronic active Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection, one with common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) with undefined inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and four with diarrhoea of unknown aetiology which included an undefined inflammatory bowel disease. Allergic patients' sera were obtained from 40 patients with bronchial asthma complicated with or without atopic dermatitis or food allergy and were used as other control sera. Intact human immunoglobulin for therapeutic use (Baxter, Deerfield, IL) was also tested.

RESULTS

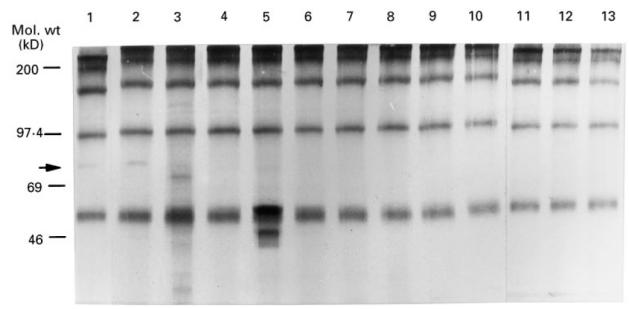

Upon Western blotting with duodenal extract as target antigen, the serum from case 1 (Fig. 1, lane 1) at admission and that from case 2 (lane 2) each developed a band at 75 kD (arrow) which was not detected with control sera from normal individuals as well as any sera from patients with allergy, diarrhoea or autoimmune disorders, including UC. Representative results with sera from normal controls and patients with different diseases are shown in Fig. 1. No other proteins which were specifically reactive with sera from both of the two cases were detected by this method.

Fig. 1.

Autoantibody against the 75-kD antigen is disease-specific. Arrow: 75-kD protein was reactive with serum from cases 1 and 2 (lanes 1 and 2, respectively), but not with sera from a variety of diseases (lanes 3–10; systemic lupus erythematosus, ulcerative colitis, Sjögren's syndrome, chronic active Epstein–Barr virus infection, bronchial asthma, dermatomyositis, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and common variable immunodeficiency, respectively), normal control (lanes 11 and 12) or γ-globulin (lane 13).

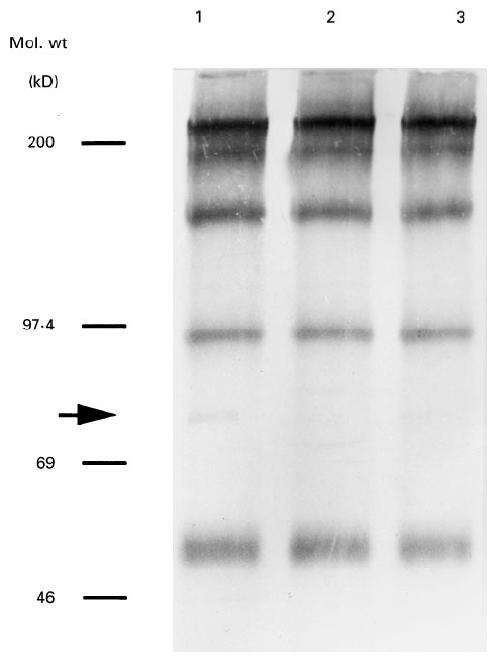

The reactivity with the 75-kD antigen of the sera from case 1 at his remission and relapse decreased considerably compared with that at his admission (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Chronological changes in reactivities of sera from case 1 with 75-kD antigen. Sera were obtained at admission (lane 1), remission (lane 2) and relapse (lane 3).

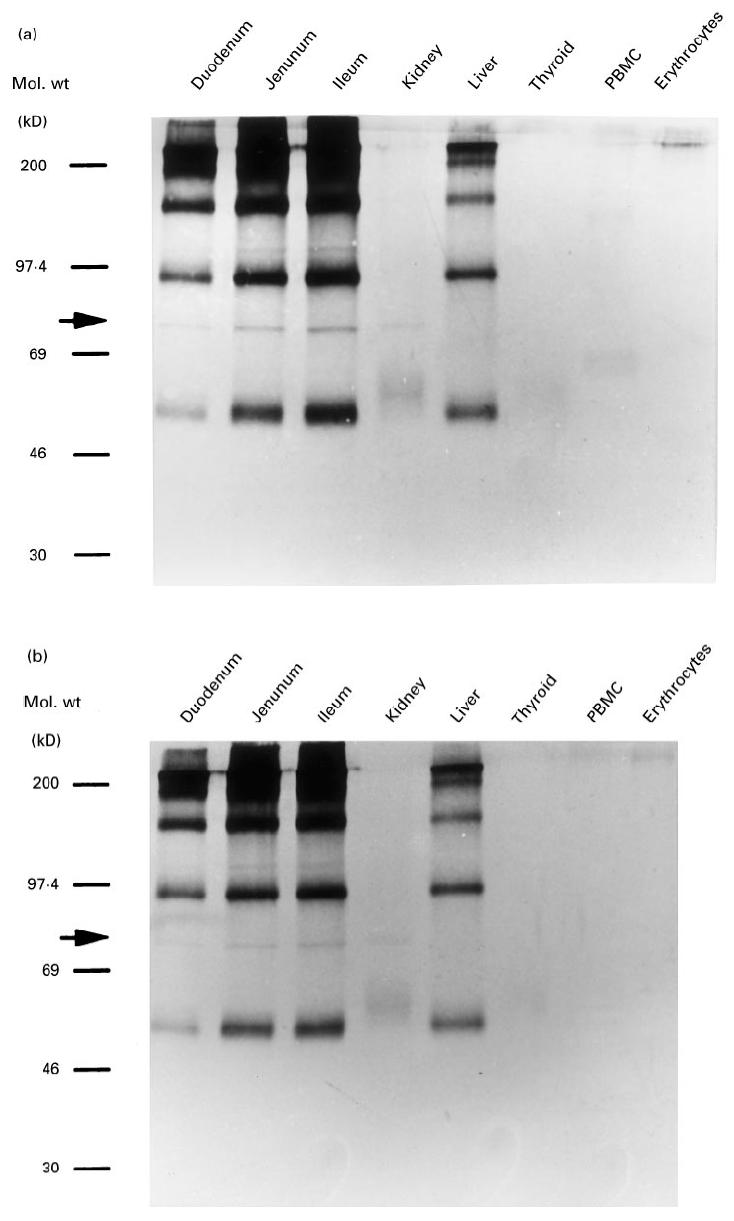

A search for the 75-kD antigen in other tissue extracts was made using sera from case 1 at his admission and those from case 2. As shown in Fig. 3, the signal at 75 kD was detected in duodenal, jejunal, ileal and renal tissues, but not in the thyroid gland, liver, PBMC or erythrocytes. This band was not detected in brain, spleen or B cell lines transformed with EBV (data not shown). Accordingly, as tested thus far, this 75-kD antigen seemed to be distributed through the whole intestine and kidney.

Fig. 3.

Tissue distribution of the 75-kD antigen. The reactivities of sera from case 1 (a) and case 2 (b) with the lysates of the indicated tissues were tested by Western blot analysis.

DISCUSSION

Recent studies have revealed the importance of AIE as a cause of intractable diarrhoea [14]. Although immunohistological studies are diagnostic, studies on autoantigen have been limited. In the present study, we identified a circulating autoantibody against the 75-kD antigen in the sera from cases 1 and 2, but not in any of the other sera, including IBD and autoimmune disorders. It was noteworthy that the same antigen (the 75-kD) was recognized by autoantibodies from unrelated patients with AIE and nephropathy. These findings suggest that the detection of autoantibody against the 75-kD antigen is AIE-specific and has at least some diagnostic value in AIE.

AIE is commonly complicated with autoimmune diseases of other organ systems [1]. In some cases, autoantibodies are detected against the tissues which are clinically or pathologically involved. Because autoimmune thyroiditis, AIHA and IDDM, all of which are common complications of AIE, were observed in our cases, it would have been expected that the autoantibody in the sera recognized a common antigen in the different tissues or cells. However, the 75-kD antigen was not detected in erythrocytes or thyroid gland. This finding suggests that autoimmune reaction against the 75-kD antigen was not implicated in the development of AIHA and thyroiditis in our cases. On the other hand, the 75-kD antigen was detected in both kidney and intestine. Previous immunohistological studies have shown that the staining pattern of intestine varies between cases, i.e. cytoplasm [2,8], brush border [2,15] and goblet cells [10]. As well, although renal damage is a common complication of AIE, the localization of staining varies from glomerulus [11] to tubular basement membrane [2,8,11] or brush border [12]. These findings suggest the heterogeneity of autoantibody formation in AIE. Furthermore, by Western blot analysis, Colletti et al. have reported that the serum from a case of AIE complicated with glomerulonephritis reacted with a 55-kD antigen in both jejunum and kidney [7]. In contrast, both of our cases were complicated with renal tubular damage. Therefore, it is possible that autoantibodies against the 55-kD and 75-kD correspond to the glomerular and tubular lesions.

Immunohistological study of serum from case 1 showed a staining of brush border of the intestine in addition to the cytoplasm of enterocytes, whereas the staining of the intestine by serum from case 2 and of the renal tubules by those from both cases was faint (data not shown). Therefore, the intracellular localization of the 75-kD autoantigen remains unclear. Concerning the differences in immunohistological staining between case 1 and case 2, it is possible that the serum from case 1 contained autoantibody against other intestine-specific cytoplasmic component(s) which was undetectable by Western blot analysis. Nevertheless, our results suggest that the intestinal and renal damage in our patients resulted from immune reactions against the common components, the 75-kD antigen, distributed in both tissues.

In case 1, serum levels of autoantibody to the 75-kD antigen remained low after the first remission and did not rise during his clinical relapse. Diarrhoea observed in case 1 rapidly responded to the administration of T cell-suppressive drugs such as cyclosporin A (CsA) or tacrolimus in combination with corticosteroid [4,5]. In several organ-specific autoimmune diseases such as SS, IDDM and multiple sclerosis, the autoantigens defined by reactivity with autoantibodies are also known to stimulate T cells [16–18]. Therefore, the effector function for the tissue damage in our cases may reside in T cell-mediated immunity rather than in autoantibody itself as described in multiple sclerosis and IDDM [15,19]. On the other hand, in the case of IDDM, it has been reported that the detection of anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase autoantibody predicts the development of insulitis and clinical diabetes mellitus [20]. In this context, in addition to the diagnostic value, the detection of autoantibody against the 75-kD antigen may predict intestinal or renal damage, even if the autoantibody itself is not implicated in tissue damage.

In conclusion, autoimmune responses against the 75-kD antigen which distributes in the intestine and kidney are disease-specific and may be implicated in the development of AIE and nephropathy. Biochemical and immunological characterization of the 75-kD antigen may provide further insights into this rare disorder.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients and their parents for their cooperation in our study. The authors also would like to thank Dr N. Kurauchi (First Department of Surgery, Hokkaido University School of Medicine) for providing tissue specimens, and Dr M. Konno (Sapporo Kousei Hospital) for providing sera from patients with Crohn's disease and Behçet's disease. This work was supported in part by Grant-in-Aid from the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Japan.

References

- 1.Powell BR, Buist NMR, Stenzel P. An X-linked syndrome of diarrhea, polyendocrinopathy and fatal infection in infancy. J Pediatr. 1982;100:731–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(82)80573-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mirakian R, Richardson A, Milla PJ, Walker-Smith JA, Unsworth J, Savage MO, Bottazzo GF. Protracted diarrhoea of infancy: evidence in support of an autoimmune variant. Br J. Med. 1986;293:1132–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.293.6555.1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Unsworth DJ, Walker-Smith JA. Autoimmunity in diarrhoeal disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1985;4:375–80. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198506000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Satake N, Nakanishi M, Okano M, et al. A Japanese family of X-linked auto-immune enteropathy with haemolytic anaemia and polyendocrinopathy. Eur J Pediatr. 1993;152:313–5. doi: 10.1007/BF01956741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kobayashi I, Nakanishi M, Okano M, Sakiyama Y, Matsumoto S. Combination therapy with tacrolimus and betamethasone for a patient with X-linked autoimmune enteropathy. Eur J Pediatr. 1995;154:594–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02074852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lachaux A, Bouvier R, Cozzani E, Loras-Duclaux I, Kanitakis J, Chevallier M, Kaiserlian D. Familial autoimmune enteropathy with circulating anti-bullous pemphigoid antibodies and chronic autoimmune hepatitis. J Pediatr. 1994;125:858–62. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81999-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colletti RB, Guillot AP, Rosen S, Bhan AK, Hobson CD, Collins AB, Russel GI, Winter HS. Autoimmune enteropathy and nephropathy with circulating anti-epithelial antibodies. J Pediatr. 1991;118:853–64. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)82195-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martini A, Scotta MS, Notarangelo LD, Maggiore G, Guarnaccia S, De Giacomo C. Membranous glomerulopathy and chronic small-intestinal enteropathy associated with autoantibodies directed against renal tubular basement membrane and cytoplasm of intestinal epithelial cells. Acta Pediatr Scand. 1983;72:931–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1983.tb09846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bousvaros A, Leichtner AN, Book L, Shigeoka A, Bilodeau J, Semeao E, Ruchelli E, Mulberg AE. Treatment of pediatric autoimmune enteropathy with tacrolimus (FK506) Gastroenterol. 1996;111:237–43. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8698205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore L, Xu X, Davidson G, Moore D, Carli M, Ferrante A. Autoimmune enteropathy with anti-goblet cell antibodies. Human Pathol. 1995;26:1162–8. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(95)90283-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellis D, Fisher SE, Smith WI, Jaffe R. Familial occurrence of renal and intestinal disease associated with tissue autoantibodies. Am J Dis Child. 1982;136:323–6. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1982.03970400041013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitton SG, Mirakion R, Larcher VF, Dillon MJ, Walker-Smith JA. Enteropathy and renal involvement in an infant with evidence of widespread autoimmune disturbance. J Pediatr Ggastroenterol Nutr. 1989;8:397–400. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198904000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laemmli U. Cleavage of structural protein during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–5. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ventura A, Dragovich D. Intractable diarrhoea in infancy in the 1990s: a survey in Italy. Eur J Pediatr. 1995;154:522–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02074826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steinman L. Multiple sclerosis: a coordinated immunological attack against myelin in the central nervous system. Cell. 1996;85:299–302. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81107-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Namekawa T, Kuroda K, Kato T, et al. Identification of Ro (SSA) 52 kDa reactive T cells in labial salivary glands from patients with Sjögren's syndrome. J Rheumatol. 1995;22:2092–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisfalen ME, DeGroot LJ, Franklin WA, Soltani K. Microsomal antigen-reactive lymphocyte line and clones derived from thyroid tissue of patient with Graves disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1988;66:776–84. doi: 10.1210/jcem-66-4-776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atkinson MA, Bowman MA, Campbell L, Darrow BL, Kaufman DL, Maclaren NK. Cellular immunity to a determinant common to glutamic acid decarboxylase and coxsackie virus in insulin dependent diabetes. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:2125–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI117567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tisch R, McDevitt H. Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Cell. 1996;85:291–7. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81106-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hagopian WA, Karlsen AE, Gottsater A, et al. Quantitative assay using recombinant human islet glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD 65) shows that 64K autoantibody positivity at onset predicts diabetes type I. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:368–74. doi: 10.1172/JCI116195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]