Abstract

Convalescent sera obtained from patients who were recently recovered from an acute measles virus infection were tested for the presence of anti-HIV-1 antibodies by Western blot analysis. While 16% (17/104) of control sera displayed reactive bands to a variety of HIV proteins, 62% (45/73) of convalescent sera demonstrated immunoreactive bands corresponding to HIV-1 Pol and Gag, but not Env antigens. This cross-reactivity appears to be the result of an active measles infection. No HIV-1 immunoblot reactivity (0/10) was observed in sera obtained from young adults several weeks after a combined measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccination. Interestingly, examination of anti-HLA typing sera specific for either class I and class II molecules revealed that 46% (19/41) of these sera contained cross-reactive antibodies to HIV-1 proteins. Absorption of measles sera with mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR)-activated lymphocytes and/or HIV-1 recombinant proteins significantly decreased or removed the presence of these HIV-1-immunoreactive antibodies. Together, these findings suggest that the immune response to a natural measles virus infection results in the production of antibodies to HIV-1 and possibly autoantigens.

Keywords: HIV-1, measles, indeterminate Western blot

INTRODUCTION

Over the past 10 years, an immunological link has been demonstrated between HIV-1 antigens and cell surface-bound HLA molecules [1–4]. While the precise mechanisms for this relationship are poorly understood, these associations are believed to result from either molecular mimicry between various HIV-1 proteins and HLA molecules, and/or a physical interaction between the virus and HLA self proteins. Regardless of the reason, this association has led to the hypothesis that AIDS is, in part, an autoimmune phenomenon in which the immune response to HIV-1 may evoke an immune response to self HLA antigens [5–8].

An association between viral and ‘self’ antigens has been shown to occur in a number of viral infections other than HIV-1 [9]. For example, common molecular sequences shared between viral proteins and myelin basic protein (MBP) are believed to be responsible for the autoimmune disease allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE), a multiple sclerosis (MS)-like disease [10]. Molecular sequence analyses have demonstrated that many viral proteins share similar antigenic epitopes with host cell proteins [11]. In addition, upon binding to HLA class II molecules, various viral and ‘self’ antigens have also been shown to act as ‘superantigens’, selectively inducing the activation of certain Vβ T cell receptor (TCR)-expressing T cell populations, as well as leading to the clonal deletion of these same T cell populations within the thymus and periphery [12–16]. Superantigenic activity has also been suggested for both HIV-1 and measles virus infections [12, 17]. Given these various associations, viral infections typically produce both in vivo and in vitro abnormalities of T cell function.

The widespread use of immunoblotting to study antibody-mediated immune responses to HIV-1 resulted in the discovery that as many as 30% of individuals, despite being non-reactive when screened by ELISA or enzyme immunosorbent assay (EIA) and who are not in a recognized high-risk category for HIV-1 infection, have antibodies to HIV-1-associated antigens [18]. The meaning of these weakly positive or ‘indeterminate’ immunoblots in apparently healthy, minimal risk individuals is uncertain. Whether an indeterminate immunoblot represents a cross-reactivity between HIV-1-associated antigens and non-HIV-1 antigens has not been definitively established.

The present study demonstrates that within the sera of patients with HIV-1 or measles virus infections, there are cross-reactive antibodies to both viral and self antigens that can be detected on an anti-HIV-1 immunoblot. Using convalescent sera from patients recovering from recent measles virus infections, indeterminate immunoblot reactivity was removed by absorption with specific HIV-1-gag proteins. Similarly, in sera obtained from AIDS patients, HIV-1 and autoreactive antibodies were removed by absorption with lymphoid cells. Furthermore, several HLA typing sera were shown to contain HIV-1-reactive antibodies that could be absorbed by purified HIV-1 proteins. Together, these results suggest that sera obtained from AIDS and convalescing measles patients contain both autoreactive and HIV-1-reactive antibodies that may contribute to viral disease pathology.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Sera

Measles convalescent sera were collected in the State of Maryland (n = 73) and Lima, Peru (n = 4). Pre-immunization and multiple post-immunization sera were obtained from young adults (n = 10; ages 23–32 years) in Cleveland, Ohio, who had been vaccinated with a live measles, mumps, rubella vaccine (M-M-R II; Merck & Co., Inc., West Point, PA). Normal, control sera (n = 104) were obtained from non-HIV-infected people living in the Washington, DC area. Sera from HIV-infected individuals (n = 3) were obtained from patients within our clinical population. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Francis Scott Key Medical Center that oversees all clinical research protocols of the Gerontology Research Center, NIA, NIH. In all cases, the collection and use of the sera also had IRB approval at the institution where the sera originated. All sera were anonymously labelled during the studies performed at the NIA. Sera were collected under sterile conditions and stored at −20°C.

Anti-HLA typing sera

Two different sources of anti-HLA typing antisera were utilized in the current studies. These various sera were commercially obtained from either Pel Freeze Clinical Systems (Brown Deer, WI) or the Howard University Genetics Laboratory (Washington, DC).

Anti-HIV-1 Western blots

Western blot (WB) analyses were performed using the Novapath Immunoblot Assay Kit (BioRad Labs, Richmond, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The kit is manufactured from HIV-1 propagated in the T lymphocyte cell line HUT-78. The partially purified virus is inactivated and disrupted with SDS and specific HIV-1 proteins separated by gel electrophoresis in the presence of SDS. Separated proteins are transferred by electroblotting onto nitrocellulose. All serum specimens, whether from HIV+ persons, anti-HLA sera or from patients recovering from measles virus infection, were run using the same procedure. In some cases, sera were run at several dilutions to appreciate better the effects of absorption with lymphoid cells. None of the individuals whose sera resulted in an indeterminate anti-HIV-1 immunoblot banding pattern were HIV-EIA- or ELISA-positive.

Absorption of sera to remove anti-measles virus antibody

One hundred microlitres of convalescent serum from each of 10 patients who had recently had measles were added to one vial of measles virus live vaccine (ATTENUVAX; Merck & Co.) that had been reconstituted with 500 μl of sterile water. The reconstituted vaccine contained not less than 1000 tissue culture infectious doses (TCID)50 and approximately 25 μg of neomycin. This vaccine is produced in chick embryo cell culture and contains no preservatives or other viral proteins, but does contain small amounts of sorbitol and hydrolysed gelatin as stabilizers. The serum–virus mixture was incubated at 37°C for 3 h, overnight at 4°C, and then was dialysed against distilled water for 24 h at 4°C. Each sample was then reduced in volume to 90 μl by vacuum centrifugation (DNA Speed-Vac; Savant Instruments, Farmingdale, NY). A control was run for each sample (the same protocol but without the addition of the ATTENUVAX). WB were run using 30 μl of each serum sample. The absorbed sera were also re-examined for their anti-measles virus antibody activity.

Removal of WB reactivity by absorption with HIV-1 recombinant proteins

Recombinant HIV-1 p18 and p24 proteins produced in a baculovirus expression system were obtained from Intracel (Cambridge, MA). One hundred microlitres of either measles convalescent sera or anti-HLA antisera were added to 100 mg of recombinant protein and incubated at 37°C for 3 h and then overnight at 4°C. Each sample was reduced to 100 μl by vacuum centrifugation. A control was done for each sample without the addition of recombinant protein. The absorbed sera were examined for immunoblot reactivity.

Removal of the IgG fraction from measles convalescent serum

Convalescent serum samples from three different patients recently recovered from measles were treated to remove the IgG fraction. HiTrap Protein G Affinity Columns (Pharmacia LKB Biotechnology, Piscataway, NJ) were washed with three volumes of deionized water and equilibrated with two volumes of starting buffer (20 mm Na phosphate pH 7.0). A 400-μl serum sample was applied to each column and run in with 5 volumes of starting buffer. Column bound IgG was eluted in one fraction with three volumes of a buffer containing 0.1 m glycine HCl pH 9.0. The eluted fraction from each column was dialysed against 6 l of dH2O for 24 h at 4°C, followed by vacuum centrifugation to reduce the volume to 200 μl. Twenty microlitres of a 1 m Tris–HCl buffer pH 9.0 were added to each 200-μl sample to preserve activity.

Absorption of anti-measles virus and anti-HIV-1 sera with lymphoid cells

Absorption with different types of cells was tested for their effect on the WB patterns. Cells used for absorption were: (i) density gradient-separated non-activated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from three HIV− donors; and (ii) 3-day-old mixed lymphocyte cultures in which there was an increase in the expression of HLA class II antigens. These activated cells were created by culturing PBMC at a final density of 2.5 × 106/ml in 30 ml of media (RPMI 1640 with 10% fetal calf-serum (FCS), 5 × 10-5m 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME) and 100 μg/ml gentamicin) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 3 days. For absorption of the sera, various numbers of cells were centrifuged into pellets and then resuspended in 0.1 ml of added serum and incubated at 4°C for 24 h. After incubation, the serum was separated from the cells by centrifugation at 3000 g for 10 min and analysed for bands on the anti-HIV-1 immunoblot.

RESULTS

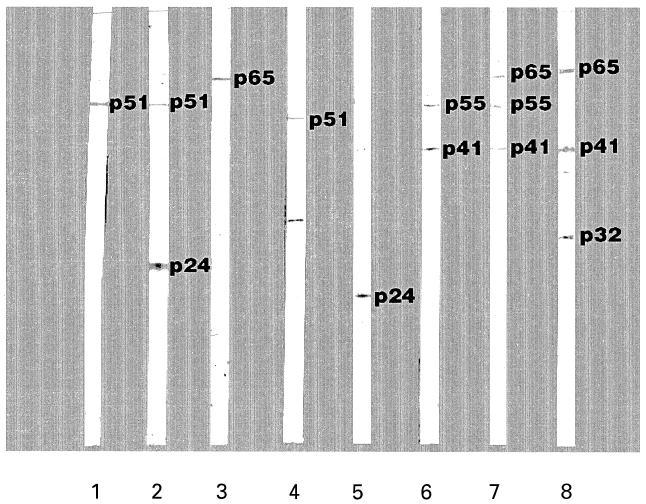

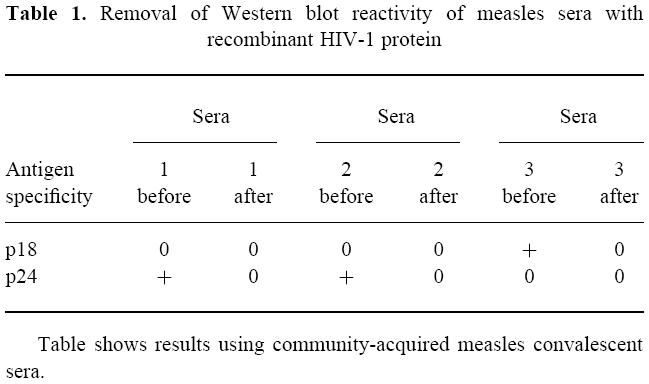

During a survey seeking possible causes for indeterminate HIV-1 WB, we noted that approximately half of the individuals who had recently recovered from a measles infection exhibited indeterminate HIV-1 immunoblots. The most prevalent HIV-1-specific bands were p18, p24, gp41 and p55. We followed up these observations by testing sera isolated from Peruvian indian children (n = 4) and children and college age adults living within the Maryland area (n = 73), all of whom had recently recovered from measles virus infections. All of the Peruvian children and 45 out of 73 (62%) of the Maryland residents produced specific immunoblot bands characteristic of indeterminate HIV-1 WB (Fig. 1). Overall, 96 bands with 14 different molecular weights were detected. The most common and dense of these bands were associated with the p24 and p65 HIV-1 antigens. Passage of three representative convalescent sera through anti-IgG affinity columns removed the HIV-1 immunoblot-reactive bands, while blotting with the eluate fraction derived from these columns produced similar bands as non-passaged sera. These results strongly suggest that band reactivity observed using measles convalescent sera was due to serum IgG. The above also strongly suggest that active measles virus infections result in the production of antibodies that are cross-reactive with HIV-1 proteins. However, it was unclear whether an active infection is a prerequisite for the production of these cross-reactive antibodies. To this end, post-immunization sera derived from 10 young adult donors recently immunized with a live measles, mumps and rubella vaccine (ATTENUVAX) were also examined using the HIV-1 immunoblots, and failed to produce any immunoreactive bands. Despite this lack of reactivity, vaccination resulted in a several fold increase in anti-measles virus antibody titres. Interestingly, absorption of several convalescent measles sera with the measles virus vaccine strain (Enders' attenuated Edmonston strain) resulted in the removal of antibodies reactive to the measles virus but not to HIV-1 antigens. In contrast, absorption of convalescent measles sera with baculovirus-derived recombinant HIV-1 p18 and p24 proteins specifically removed the HIV-1 immunoblot-reactive bands present within convalescent measles sera (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Representative HIV-1 immunoblot using sera obtained from various groups of individuals, some who had had a recent measles infection. Lanes 1, 2, and 3, sera from children and young adults from Maryland; lanes 4 and 5, sera samples from individuals who had had a measles infection but who were further in the post-recovery period; lanes 6, 7, and 8, sera samples from Peruvian children who had had a measles infection.

Table 1.

Removal of Western blot reactivity of measles sera with recombinant HIV-1 protein

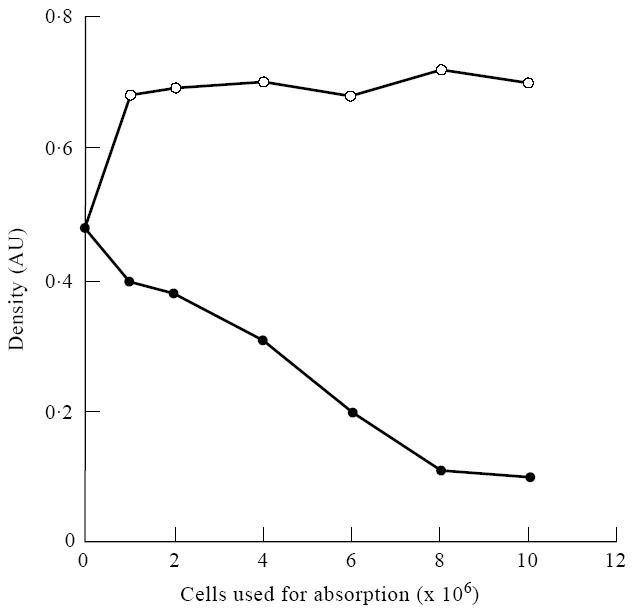

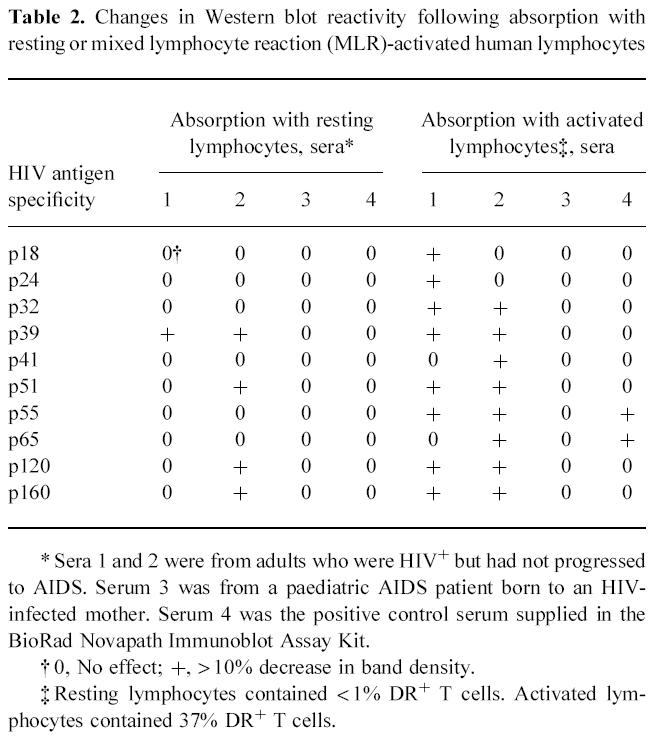

Absorption of convalescent measles sera with either resting or activated lymphoid (mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR)) cells removed most of the HIV-1 immunoblot-reactive antibodies from the immunoreactive sera (Fig. 2, Table 2). Absorption of a strongly positive control serum provided with the HIV-1 immunoblot kit as well as sera derived from a paediatric AIDS patient with MLR-activated lymphocytes failed to affect immunoblot band intensity. However, absorption of two HIV-1+ sera that produced weaker bands on HIV-1 immunoblots with MLR-activated lymphocytes demonstrated a slight decrease in some band intensities. Based on these absorption studies, these results suggest that HIV-1 cross-reactive antibodies present in the convalescent sera obtained from measles patients possess autoreactive antibodies that react with or bind to molecules on the surface of human lymphocytes (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Changes seen in the density of the p18 band on an HIV-1 Western blot after absorption of a serum from an HIV-1-infected person with non-activated normal lymphocytes or mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR)-activated lymphocytes. There were 37% DR+ cells in the MLR-activated culture and < 1% in the non-activated lymphocytes. As seen in this figure, the density of the band changed when the activated (DR+) cells were used for absorption, while little change occurred when non-activated cells were used. ○, Non-activated cells; •, activated cells 37% DR+.

Table 2.

Changes in Western blot reactivity following absorption with resting or mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR)-activated human lymphocytes

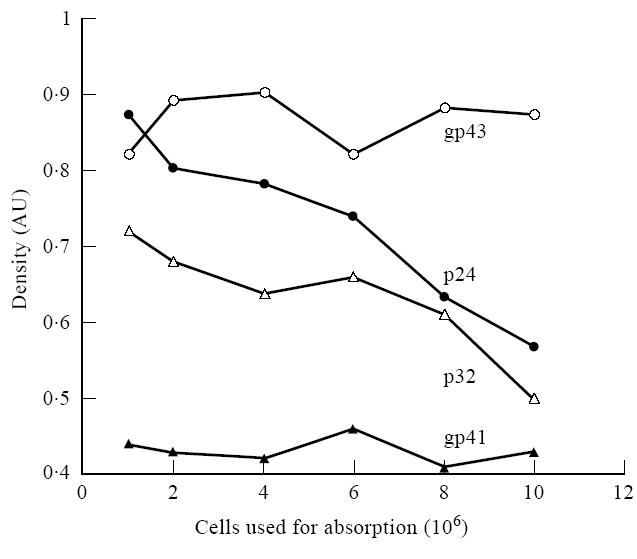

Fig. 3.

Changes seen in various HIV-1 bands on an HIV-1 Western blot when the serum from an HIV-1-infected patient was absorbed using variable numbers of mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR)-activated normal lymphocytes. This figure complements the data presented in Fig. 2 and shows that the density of some of the bands on the Western blot change while others do not when the serum from an HIV-1-infected person is absorbed with activated lymphoid cells.

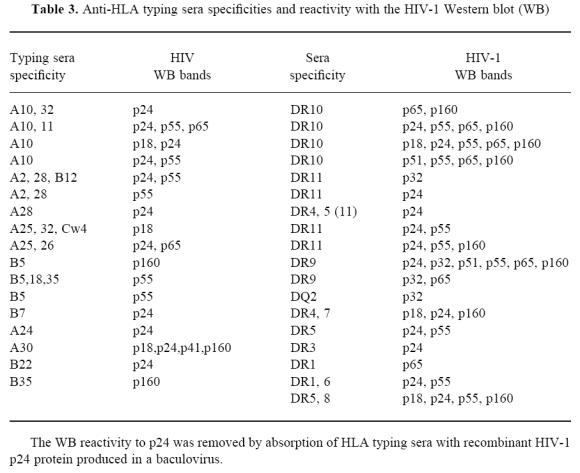

While it is unclear which lymphocyte surface molecules are reactive with HIV-1 antigens and HLA, previous studies have suggested an immunoreactive association between HIV-1 antigens and HLA molecules [5]. To examine this question, we tested 41 different HLA typing sera derived from multiparous women on immunoblots for possible cross-reactivity with various HIV-1 proteins. The HIV-1 blot immunoreactivity of the anti-HLA antisera failed to display an indiscriminate binding pattern on the HIV-1 immunoblots, but did, in many cases, yield specific and reproducible bands on the immunoblots. Curiously, HLA typing sera with the same putative specificity often produced dissimilar HIV-1 immunoblot band patterns (Table 3). Overall, about 2/3 of all the typing sera displayed some reactivity with Pol and Env region antigens, with the most common and strongest reactions being to the Gag antigens p24 and p55. The above results demonstrate that naturally derived HLA-reactive antisera possess HIV-1-specific antibodies that may be due to cross-reactive epitopes between HIV-1 and various HLA molecules.

Table 3.

Anti-HLA typing sera specificities and reactivity with the HIV-1 Western blot (WB)

DISCUSSION

Sera from up to 30% of individuals in non-risk categories for HIV-1 produce one or more bands on anti-HIV-1 immunoblots [18, 19]. While the causes of these indeterminate immunoblot patterns are generally unknown, similar results have been reported using sera obtained from patients with malaria [20–22] and leishmaniasis [23]. Polyclonal B cell activation has also been shown to produce anti-HIV-1 antibodies in HIV-1− individuals [24]. One suggestion as to the origin of indeterminate HIV-1 immunoblot reactivity is that it is due to antibodies produced following exposure to defective human immunodeficiency viruses or to distantly related animal retroviruses [25]. In the present study, we show that measles virus infection produces antibodies that cross-react with HIV-1 antigens. Following ‘natural’ measles virus infections, children and young adults develop circulating IgG antibodies that result in specific immunoblot reactivity on HIV-1 immunoblots. However, due to the limited availability of freshly isolated measles patient sera, only 73 Maryland and four Peruvian indian samples were provided by the Maryland State Health Department for these studies. Thus, this small and non-age-matched sample number has prevented a direct comparison between the various donors for environmental, physiological and genetic similarities that may account for the differences observed within our assays. In contrast, individuals ‘vaccinated’ with the live measles, mumps and rubella vaccine failed to produce HIV-1-reactive antibodies. This discrepancy may be due to differences in the ability of wild-type and vaccine strains of measles virus to infect cells. Wild-type measles virus has previously been shown to infect host leucocytes, particularly monocytes [26] quite effectively, while vaccine strain virus failed to infect any leucocytic population [27–31]. Therefore, it also seems quite possible that the route of viral entry, the level of virus exposure, and the effects of viral load on immune cells may contribute to the development of HIV-1 cross-reactive antibodies.

There are a number of similarities between HIV-1 and measles virus infections. Both viruses cause significant immune suppression, infect CD4+ lymphocytes, CNS tissue and monocytes/macrophages both in vivo and in vitro [31–36]. Our results also demonstrate that infections due to either of these viruses result in the appearance of cross-reactive serum antibodies which produce immunoreactive bands on an HIV-1 immunoblot. The HIV-1-reactive antibodies present in the sera may not be entirely specific for viral antigens, as absorption experiments suggest additional reactivity to self-antigens. These antibodies may be generated through the sharing of amino acid homologies between the virus and host [1, 10] or through the cytokine-modulating properties of the viruses and their products [37]. In addition, studies by Arthur et al. [38] have suggested the newly budding HIV-1 viruses possess host-derived cell surface molecules, such as HLA-DR and β2-microglobulin on their capsid surface. Also, studies by Orentas & Hildreth [39], using a MoAb-based capture assay, have demonstrated class I and II MHC proteins associated with both HIV-1 and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) [39]. Perhaps these viral-associated host molecules result in new epitope(s) formation, leading to the generation of autoreactive antibodies. Immunoblot analysis of the sera from HIV and measles patients with purified HLA molecules are currently under investigation. HIV-1 is associated with a wide range of autoimmune phenomena that are correlated with the loss of CD4+ cells and disease progression [7, 8, 40].

Furthermore, HLA typing sera also gave a positive reaction on HIV-1 immunoblots used in our studies. Sera from HIV-1-infected individuals at different stages of the illness react with both MHC class I molecules and class II-derived peptides. MoAbs to gp41-derived sequences cross-react with MHC class II-derived peptides and recognize native class II molecules [1, 5]. As these HLA-reactive antibodies are generally obtained from multiparous females who have generated them during previous pregnancies, this cross-reactivity is not completely unexpected. As previously reported, indeterminate HIV-1 immunoblots may be attributable to the presence of HLA antigens on the immunoblot [1]. Unlike the report of Drabick & Baker [41], the NovaBlot HIV-1 immunoblot strips displayed no 43–45-kD bands and only occasional 56-kD bands that may represent class I and class II molecules, respectively. The MHC specificities we observed were generally associated with putative HIV-1 gag and pol proteins rather than HIV-1 env antigens.

Though our study did not directly demonstrate ‘molecular mimicry’ between HLA and HIV-1, it does support and extend the previous studies published by other laboratories. If molecular mimicry between HIV-1 and HLA class II antigens exists, this similarity may lead to the generation of autoantibodies in HIV-1-infected individuals resulting in increased immune suppression and modulation [1, 5].

In conclusion, viral infections provoke complicated immune responses. Understanding these responses can lead to more efficacious vaccine strategies and a better understanding of the pathogenesis of viral induced illness. The association of HIV-1 and tissue histocompatibility antigens is especially interesting considering recent provocative experimental evidence suggesting that a tissue antigen response can be protective for HIV-1 disease and that treating this response in an infected person can prolong their disease-free period [42].

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs Diane Griffin and Brian Ward for providing convalescent measles sera, Dr Armead Johnson who provided the HLA specificities of the typing sera, Ms Suzanne Strutt and the late Ms Charlotte Adler who prepared the figures, and Dr Dennis D. Taub for critical review and advice relating to the manuscript.

References

- 1.Golding H, Shearer GM, Hillman K, et al. Common epitope in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) I-gp41 and HLA class II elicits immunosuppressive autoantibodies capable of contributing to immune dysfunction in HIV-1-infected individuals. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:1430–5. doi: 10.1172/JCI114034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kion TA, Hoffman GW. Anti-HIV and anti-anti-MHC antibodies in alloimmune and autoimmune mice. Science. 1991;253:1138–40. doi: 10.1126/science.1909456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chicz RM, Urban RG, Lane WS, Gorga JC, Ster MLJ, Vignali DA, Strominger JML. Predominant naturally processed peptides bound to HLA-DR1 are derived from MHC-related molecules and are heterogeneous in size. Nature. 1992;358:764–8. doi: 10.1038/358764a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chicz RM, Urban RG, Gorga JC, Vignali DA, Lane WS, Strominger JML. Specificity and promiscuity among naturally processed peptides bound to HLA-DR alleles. J Exp Med. 1993;178:27–47. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Golding H, Robe FA, Gates FT, III, Linder W, Beining PR, Hoffman T, Golding B. Identification of homologous regions in human immunodeficiency virus I gp41 and human MHC class IIβ 1 domain. I. Monoclonal antibodies against the gp41-derived peptide and patients' sera react with native HLA class II antigens, suggesting a role for autoimmunity in the pathogenesis of acquired immune deficiency syndrome. J Exp Med. 1988;167:914–23. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.3.914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Habeshaw JA, Dalgleish AG, Bountiff ML, Newell AML, Wilks D, Walker MLC, Manca F. AIDS pathogenesis: HIV envelope and its interaction with cell proteins. Immunol Today. 1990;11:418–24. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(90)90162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morrow WJ, Isenberg DA, Sobol RE, Stricke RB, Kieber-Emmons T. AIDS virus infection and autoimmunity: a perspective of the clinical, immunological, and molecular origins of the autoallergic pathologies associated with HIV disease. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1991;58:163–80. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(91)90134-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schattner A, Bentwich Z. Autoimmunity in human immunodeficiency virus infection. Clin Aspects Autoimmun. 1993;5:19–27. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ilonen J, Mäkelä MJ, Ziola B, Salmi AA. Cloning of human T cells specific for measles virus haemagglutinin and nucleocapsid. Clin Exp Immunol. 1990;81:212–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1990.tb03320.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujinami RS, Oldstone MBA. Amino acid homology between the encephalitogenic site of myelin basic protein and virus: mechanism for autoimmunity. Science. 1985;230:1043–5. doi: 10.1126/science.2414848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sette A, Buus S, Appella E, Smith JA, Chesnut R, Miles C, Colon SM, Grey HM. Prediction of major histocompatibility complex binding regions of protein antigens by sequence pattern analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:3296–300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.9.3296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imberti L, Sottini A, Bettinardi A, Puoti M, Primi D. Selective depletion in HIV infection of T cells that bear specific T cell receptor Vβ sequences. Science. 1991;254:860–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1948066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abe R, Foo-Philips M, Granger LG, Kanagawa O. Characterization of the Mlsf system I. A novel “polymorphism” of endogenous superantigens. J Immunol. 1992;149:3429–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foo-Philips M, Kozak CA, Principato MA, Abe R. Characterization of the Mlsf system II. Identification of mouse mammary tumor virus proviruses involved in the clonal deletion of self- Mlsf-reactive T cells. J Immunol. 1992;149:3440–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lafon M, Lafage M, Martinez-Arends A, Ramirez R, Vuillier F, Charron D, Lotteau V, Scott-Algara D. Evidence for a viral superantigen in humans. Nature. 1992;358:507–10. doi: 10.1038/358507a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dalgleish AG, Wilson S, Gompels M, Ludlam C, Gazzard B, Coates AM, Habershaw J. T-cell receptor variable gene products and early HIV-1 infection. Lancet. 1992;339:824–8. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90277-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ura Y, Hara T, Nagata M, Mizuno Y, Ueda K, Matsuo M, Mori Y, Miyazaki S. T cell activation and T cell receptor variable region gene usage in measles. Acta Paediatr Jpn. 1992;34:273–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.1992.tb00958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Midthun K, Garrison L, Clements ML, Farzadegan H, Fernie B, Quinn T. AIDS Vaccine Trials Network. Frequency of indeterminate Western blot tests in healthy adults at low risk for human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Infect Dis. 1990;162:1379–82. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.6.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burke DS, Redfield RR, Putman P, Alexander SS. Variations in western blot banding patterns of human T-cell lymphotropic virus type III/lymphadenopathy-associated virus. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:81–84. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.1.81-84.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biggar RJ, Gigase PL, Melbye M, et al. ELISA HTLV retrovirus antibody reactivity associated with malaria and immune complexes in healthy Africans. Lancet. 1985;2:520–3. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)90461-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biggar RJ, Saxinger C, Sarin P, Blattner WA. Non-specificity of HTLV III reactivity in sera from rural Kenya and eastern Zaire. East Afr Med J. 1986;63:683–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parry JV, Richmond J, Edwards N, Noone A. Spurious malarial antibodies in HIV infection. Lancet. 1992;340:1413–4. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92602-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christie IL, Palmer SJ, Voller A, Banatvala JE. False-positive serology and HIV infection. Lancet. 1993;341:441–2. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)93042-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jehuda-Cohen T, Slade BA, Powell JD, et al. Polyclonal B-cell activation reveals antibodies against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) in HIV-1 seronegative individuals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:3972–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.10.3972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sherman MP, Dock NL, Ehrlich GD, Sninsky JJ, Brothers C, Gillsdorf J, Bryz-Gornia V, Poiesz BJ. Evaluation of HIV type 1 Western blot-indeterminate blood donors for the presence of human or bovine retroviruses. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1995;11:409–14. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Esolen LM, Ward BJ, Moench TR, Griffin DE. Infection of monocytes during measles. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:47–52. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamanouchi K, Egashira Y, Uchida N, Kodoma H, Kobune F, Hayami M, Fukuda A, Shishido A. Giant cell formation in lymphoid tissues of monkeys inoculated with various strains of measles virus. Jpn J Med Sci Biol. 1970;23:131–45. doi: 10.7883/yoken1952.23.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamanouchi K, Chino F, Kobune F, Kodama H, Tsuruhara T. Growth of measles virus in the lymphoid tissues of monkeys. J Infect Dis. 1973;128:795–9. doi: 10.1093/infdis/128.6.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Osunkoya BO, Adeleye GI, Adejumo TA, Salimonu LS. Studies on leukocyte cultures in measles. II. Detection of measles virus antigen in human leucocytes by immunofluorescence. Arch Gesamte Virusforsch. 1974;44:323–9. doi: 10.1007/BF01251013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacobson S, McFarland HF. Measles virus infection of human peripheral blood lymphocytes: importance of the OKT4+ T-cell subset. In: Bishop DHL, Compans RW, editors. Nonsegmented negative strand viruses: paramyxoviruses and rhabdoviruses. New York: Academic Press; 1984. pp. 435–42. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Forthal DN, Aarnaes S, Blanding J, de la Maza L, Tilles JG. Degree and length of viremia in adults with measles. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:421–4. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.2.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sha BE, Harris AA, Benson CA, et al. Prevalence of measles antibodies in asymptomatic human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:973–5. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.5.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McChesney MB, Oldstone MB. Virus-induced immunosuppression: infections with measles virus and human immunodeficiency virus. Adv Immunol. 1989;45:335–80. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60696-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spear GT, Ou CY, Kessler HA, Landay AL. Analysis of lymphocytes, monocytes and neutrophils from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected persons for HIV DNA. J Infect Dis. 1990;162:1239–44. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.6.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ihara T, Yasuda N, Kitamura K, Ochiai H, Kamiya H, Sakurai M. Prolonged viremic phase in children with measles (letter) J Infect Dis. 1992;166:941. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.4.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Griffin DE, Ward BJ. Differential CD4 T cell activation in measles. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:275–81. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.2.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Segal BM, Klinman DM, Shevach EM. Microbial products induce autoimmune disease by an IL-12-dependent pathway. J Immunol. 1997;158:5087–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arthur LO, Bess JW, Jr, Sowder RC, II, Benveniste RE, Mann DL, Chermann JC, Henderson LE. Cellular proteins bound to immunodeficiency viruses: implications for pathogenesis and vaccines. Science. 1992;258:1935–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1470916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Orentas RJ, Hildreth JEK. Association of host cell surface adhesion receptors and other membrane proteins with HIV and SIV. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1993;9:1157–65. doi: 10.1089/aid.1993.9.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morrow WJW, Isenberg DA, Sobol RE, Stricker RB, Kieber-Emmons T. AIDS virus infection and autoimmunity: a perspective of the clinical, immunological, and molecular origins of the autoallergic pathologies associated with HIV disease. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1991;58:163–80. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(91)90134-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Drabick JJ, Baker JR., Jr HLA antigen contamination of commercial Western blot strips for detecting human immunodeficiency virus. J Infect Dis. 1989;159:357–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.2.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Andrieu JM, Even P, Venet A, et al. Effects of cyclosporin on T-cell subsets in human immunodeficiency virus disease. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1988;47:181–98. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(88)90071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]