Abstract

Our objective was to study whether CD4+ or CD8+ T cells expressing particular T cell receptors (TCR) would accumulate in the lungs of patients with allergic asthma following allergen exposure. We thus analysed the TCR Vα and Vβ gene usage of CD4+ and CD8+lung and peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) of eight patients with allergic asthma before and 4 days after inhalation challenge with the relevant allergen. Lung cells obtained by bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and paired PBL samples were analysed by flow cytometry using a panel of anti-TCR V-specific monoclonal antibodies that encompass ≈ 50% of the T cell repertoire. Lung-limited T cell expansions were recorded in both the CD4+ and the CD8+ subsets. In BAL CD8+, out of a total of 126 analyses, the number of T cell expansions increased from two to 11 after challenge, some of them dramatic. In BAL CD4+ the frequency of expansions was moderately increased already before challenge, but remained unchanged. A few expansions that tended to persist were noted in PBL CD8+. When analysing the overall change in TCR V gene usage the largest changes were also recorded in the BAL CD8+ subset. Specific interactions between T cells and antigens may lead to an increased frequency of T cells using selected TCR V gene segments. In this study we demonstrate that following allergen bronchoprovocation in allergic asthmatic subjects, T cell expansions preferentially emerge in the lung CD8+ T cell subset.

Keywords: allergic asthma, T cell expansion, T cell receptor

INTRODUCTION

Asthma is a syndrome characterized by intermittent, reversible airway obstruction and by airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation. In the asthmatic airways, there is a mixed cellular infiltrate dominated by eosinophils [1]. T cells have been suggested to orchestrate the inflammatory response in asthma through their ability to secrete cytokines such as IL-4, which promotes B cell switch to IgE production, and IL-5, which is crucial for the terminal differentiation and activation of eosinophils with subsequent inflammatory mediator release and airway damage [2]. In asthmatic patients, T cells expressing activation markers are increased in number both when recovered by lavage [3] and in mucosal tissue biopsies [4], with positive correlations between the numbers of activated T cells, eosinophils, and the degree of bronchial hyperresponsiveness [5]. Treatment with inhaled corticosteroids leads to decreased bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) T cell activation [6].

T lymphocytes recognize antigens in the form of peptides bound to a MHC molecule on the surface of an antigen-presenting cell (APC). CD4+T cells interact with the combination of peptide and MHC class II molecule (in man, HLA-DR, -DP and -DQ), whereas CD8+T cells react with cells bearing MHC class I (HLA-A, -B and -C). The T cell receptor (TCR) responsible for antigen recognition is a clonally distributed heterodimer. The most common type of TCR consists of an α and a β polypeptide chain. Each chain has a constant and a variable part, the latter one interacting with the antigen [7]. The genes coding for the TCR α and β variable parts consist of several variable (V), joining (J) and, for the β-chain, diversity (D) segments [8]. The random combination of V, D and J segments, and the random addition and/or deletion of nucleotides at the V–D–J junctions explain the enormous diversity of TCR. There exist in man about 32 Vα and 26 Vβ functional gene segment families [9]. Using antibodies, it is possible to analyse the expression of different Vα and Vβ segments. In peripheral blood, each of the individual TCR V gene segments is normally used by 1–8% of the T lymphocytes [10].

Our objective was to study the role of T cells in the pathogenesis of allergic asthma by analysing the T cell repertoire in the lung compared with that in the blood, before as well as after inhalation provocation with the relevant allergen.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

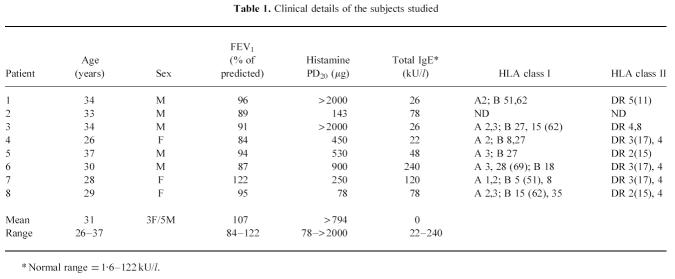

Eight non-smoking atopic subjects with mild asthma and skin prick test and radioallergosorbent test (RAST)-confirmed allergy to animal dander participated, seven with previously documented early asthmatic reactions (EAR) and one with dual asthmatic reactions following allergen bronchoprovocation. The patients were recruited from the out-patient clinic at the Division of Respiratory Medicine, Karolinska Hospital, Stockholm. Subjects gave informed consent to participate in the study, which was approved by the Local Ethics Committee. Their asthma was stable and, for inclusion, the forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) was required to be more than 75% of predicted normal. None of the patients had continuous asthmatic symptoms. A majority of patients only experienced symptoms when exposed to cat or dog. All patients were asymptomatic at the time of the first BAL. Bronchial hyperresponsiveness to histamine with a PD20 FEV1 of < 1100 μg (provocative dose causing a 20% fall in FEV1) or reversible airway obstruction (> 15% increase in FEV1 after inhalation of β2-agonist) was demonstrated within 1 month before BAL (except for one patient, where lung function was determined 5 months before BAL). Their asthma was controlled by β2-agonists taken as requested. No patient was undergoing steroid treatment, nor had anyone undergone immunotherapy. Two patients had had infections that resolved 5 weeks before bronchial provocation. Baseline characteristics are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical details of the subjects studied

Study design and allergen provocation

Peripheral blood and lymphocytes recruited by BAL were obtained 2–3 weeks before and 4 days after inhalation provocation with allergen, in order to allow the in situ proliferation of lung T cells. The bronchoprovocation procedure has been described elsewhere [11]. In brief, challenges started by the inhalation of diluent. Provided FEV1 did not change by more than 10%, half-log increments in the cumulated dose of allergen were inhaled every 15 min until the FEV1 value fell by at least 20% from post-diluent baseline. Rescue treatment was generally not given, i.e. only one subject inhaled short-acting β2-agonist 1 h after the challenge. For monitoring of possible late asthmatic reactions (LAR), measurements of peak expiratory flow rates (PEFR) were obtained. The bronchoprovocations were always conducted at the same time in the morning. Patients were not allowed to use inhaled β2-agonists for at least 8 h prior to a challenge.

BAL procedure and handling of cells

This was performed as described [12]. Briefly, bronchoscopy was carried out with a flexible fibreoptic bronchoscope under local anaesthesia. The bronchoscope was wedged in a bronchus in the middle lobe and sterile PBS solution at 37°C was instilled in six aliquots of 50 ml. After each instillation the fluid was gently aspirated and collected in a siliconized plastic bottle placed on ice. The fluid was strained through a double layer of Dacron nets and then centrifuged at 400 g for 5 min at 4°C and resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium (GIBCO, Paisley, UK). The cells were counted in a Bürker chamber, and total cell viability (mean = 90%) was determined by trypan blue exclusion. Smears for differential counts were prepared by cytocentrifugation (Cytospin 2; Shandon, Runcorn, UK) at 20 g for 3 min, whereafter cells were stained with May–Grünwald–Giemsa. Peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) were separated from heparinized peripheral blood by Ficoll–Hypaque (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) gradient centrifugation, washed twice and diluted in RPMI 1640.

Rechallenge

The procedure for obtaining BAL and PBL samples before and after challenge was repeated in patients 1, 4 and 5 after 10 months.

Immunofluorescence and flow cytometry

Anti-TCR Vα2.3-, Vβ3-, Vβ5.1-, Vβ5.2/5.3-, Vβ5.3-, Vβ6.7-, Vβ8.1-, Vβ12.1-specific MoAbs were obtained from T Cell Sciences (Cambridge, MA). The anti-TCR Vβ2-, Vβ6.1-, Vβ13.1-, Vβ13.6-, Vβ14-, Vβ17-, Vβ18-, Vβ20-, Vβ21.3-, and Vβ22-specific MoAbs were purchased from Immunotech (Luminy, France), and the anti-Vα 12.1 MoAb from Serotec (Oxford, UK). Anti-CD4 MoAbs were conjugated with either PerCP (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) or with RPE-Cy5 (Dakopatts, Glostrup, Denmark). PE-conjugated anti-CD8 MoAb, and FITC-conjugated F(ab′)2 fragments of rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin, were obtained from Dakopatts. Normal mouse serum (NMS) from BALB/c mice was used as negative control at a dilution of 1:500 in PBS. The OKT3 (CD3) hybridoma, used for positive controls, was acquired from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD).

The staining procedure is described in detail elsewhere [13]. Briefly, cells were incubated with unlabelled TCR V-specific MoAb and washed twice; FITC-conjugated F(ab′)2 fragments of rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin were added for detection of bound antibodies. NMS, diluted 1:500, was used to block remaining rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin before adding the PerCP (or RPE-Cy5)-conjugated anti-CD4 and PE-conjugated anti-CD8 MoAbs. After three washings cells were fixed in PBS with 1% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 0.5% formaldehyde. Cells were analysed in a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). Lymphocytes were gated by forward and side scatter. NMS was used as a negative control (in all cases < 1%). The panel of TCR V-specific MoAbs covers ≈ 50% of the αβ T cells in normal peripheral blood.

Definition of T cell expansion

Reference values for MoAb reactivity were established from TCR V analyses on lymphocytes from 79 healthy adult Scandinavian blood donors [10]. T cell expansions were defined as an anti-TCR V MoAb reactivity at least three times higher than the corresponding median reactivity in PBL from healthy blood donors, or any value > 15%. This definition takes into consideration that TCR Vβ segments are normally expressed at different levels. The definition was used to enable comparisons of numbers of expansions in different cell subsets before and after allergen challenge.

Since the panel of antibodies to TCR Vα and Vβ segments does not cover the complete repertoire, expansions of T cells expressing other V gene segments are not recorded directly, but can be postulated if the total coverage of the antibody panel is substantially less than expected. In this study, we used the arbitrary limit of a decrease in panel coverage by > 10% of all CD4+ or CD8+ cells, respectively, between two measurements in the same patient as a sign of a hidden expansion. Alternatively, hidden expansions were also defined when the panel coverage decreased at the same time as detectable expansions occurred (paradoxical change). In the calculations of total panel coverage, all anti-Vα and Vβ antibody reactivities are summed (for CD4+and CD8+subsets separately), and only V-segments that were analysed both before and after challenge are included.

Delta value

To determine in which cell population the mean change in TCR V gene segment usage was highest, a delta value [14] was computed as follows: for each cell population, e.g. BAL CD4+, a table was constructed with a column for each of the TCR V antibodies used (Vα2.3, Vα12.1, Vβ2, etc.) and a row for each patient. Each value in this matrix showed the difference in antibody reactivity before and after challenge. All these values were then summed, and divided by the total number of TCR V stainings. Thus, a specific delta value, reflecting the average change of TCR V usage, was obtained for each of the cell populations PBL CD4+, PBL CD8+, BAL CD4+and BAL CD8+.

HLA typing

HLA class I (HLA-A, B and C) were determined by the microlymphocytotoxicity technique. Class II (HLA-DR) typing was performed on DNA using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques and amplification with sequence-specific primers [15].

Statistical analysis

The Mann–Whitney non-parametric test was used to compare the total number of BAL cells, percentage of lymphocytes and of CD3+, CD4+and CD8+cells between samples from lung and blood, and also for the delta values. Wilcoxon's signed rank test was used for comparisons of before and after treatment. The χ2 test was used for comparisons of frequencies of T cell expansions in different cell subsets. Tenth and 90th percentiles are abbreviated P10 and P90.

RESULTS

Clinical parameters

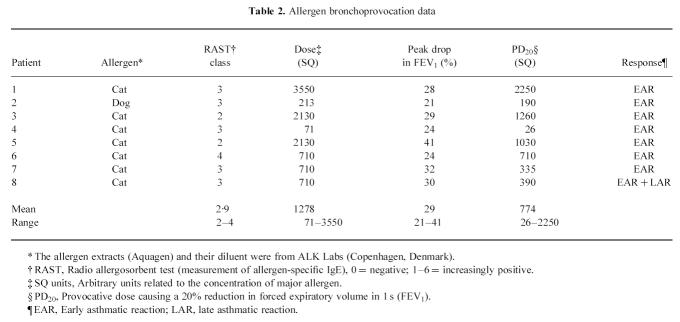

All subjects tolerated the allergen challenge and the two bronchoscopies well. Allergen used for challenge, cumulative allergen dose, peak drop during the EAR and the PD20 values are presented in Table 2. None had persisting airway obstruction at the second bronchoscopy performed 4 days after challenge.

Table 2.

Allergen bronchoprovocation data

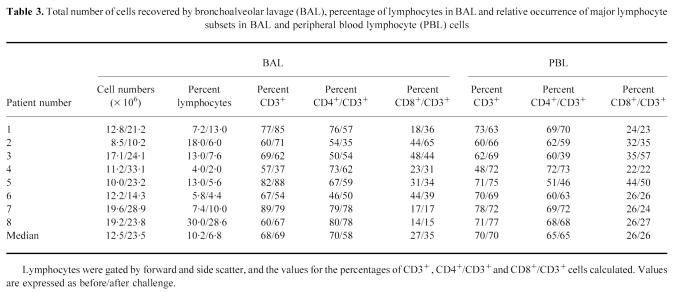

BAL and PBL lymphocytes

The total number of cells recovered by BAL, expressed as median value (P10–P90), before and after allergen challenge were 12.5 (9.0–19.5) × 106, and 23.5 (11.4–31.8) × 106, respectively (P < 0.05). The percentage of lymphocytes in the BAL fluid was 10.2 (4.5–26.4) before and 6.8 (2.7–23.9) after challenge (NS). The data for individual patients, including the relative numbers of CD3+(i.e. T cells), CD4+/CD3+and CD8+/CD3+cells are depicted in Table 3. No significant changes in the relative occurrences of these lymphocyte subsets could be detected in either BAL or PBL, although there was a tendency to increased relative numbers of CD8+cells in BAL, and a corresponding decrease in the CD4+population.

Table 3.

Total number of cells recovered by bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), percentage of lymphocytes in BAL and relative occurrence of major lymphocyte subsets in BAL and peripheral blood lymphocyte (PBL) cells

The CD4/CD8 ratios in PBL and BAL, before and after challenge, were calculated. The median value (P10–P90) of the CD4/CD8 ratio for PBL before challenge was 2.4 (1.4–3.2) and remained unchanged at 2.4 (0.8–3.2) after challenge, whereas the ratio in BAL decreased from 2.7 (1.0–5.4) to 1.6 (0.7–5.0) (NS).

TCR V gene usage

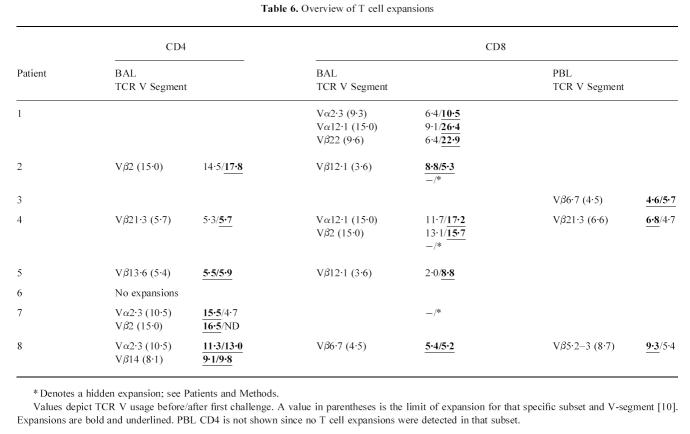

The total number of expansions in the eight subjects before and after challenge was calculated for the following cell populations: PBL CD4+, PBL CD8+, BAL CD4+and BAL CD8+(Table 4). Reference values for the incidence of T cell expansions are also included in Table 4. Before challenge, we noted a high incidence of BAL CD4+expansions.

Table 4.

Number and frequency of T cell expansions based on ≈ 120 T cell receptor (TCR) V analyses in each subset

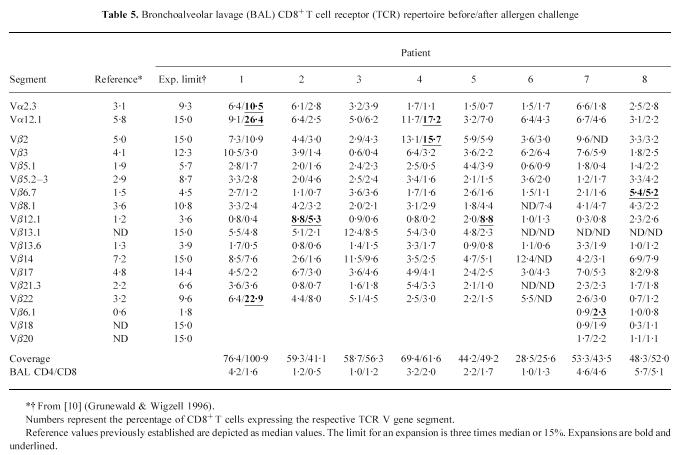

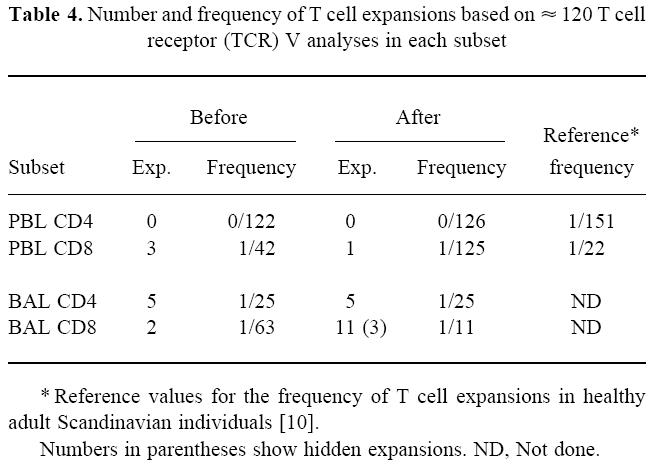

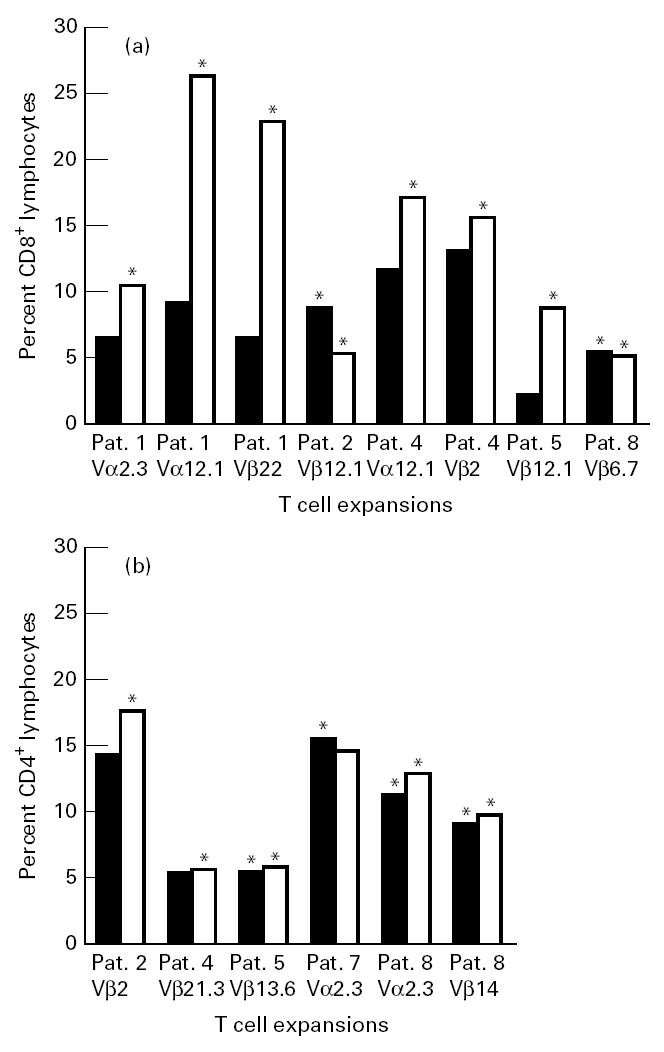

The largest changes in TCR V gene usage before and after challenge, in terms of T cell expansions, occurred in the BAL CD8+cells (Table 5). Here, two minor expansions before challenge remained, and nine new expansions emerged after allergen challenge. Three of these were hidden expansions in the BAL CD8+cells of patients 2, 4 and 7. BAL CD8+was the only subset where we found significantly more expansions after challenge than before (P < 0.05). Some of the BAL CD8+expansions were dramatic, e.g. after challenge in patient 1, 26.4% of the BAL CD8+cells expressed Vα 12.1 and 22.9% expressed Vβ 22, while in patient 4, 17.2% expressed Vα 12.1. Figure 1 shows the gating of PBL and BAL lymphocytes, as well as an emerging T cell expansion.

Table 5.

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) CD8+ T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire before/after allergen challenge

Fig. 1.

Upper panel: Flow cytometry profiles demonstrating the forward scatter, side scatter gating of peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) lymphocytes (patient 7). Lower panel: FACS analysis of BAL lymphocytes demonstrating the emergence of a T cell expansion in patient 1. On the abscissa (FL1) FITC-stained Vα12.1 is shown; on the ordinate (FL2) PE-stained CD8. Before challenge Vα12.1 stained 9.1% of the CD8+ T cells. After challenge Vα12.1 stained 26.4% of the CD8+ T cells.

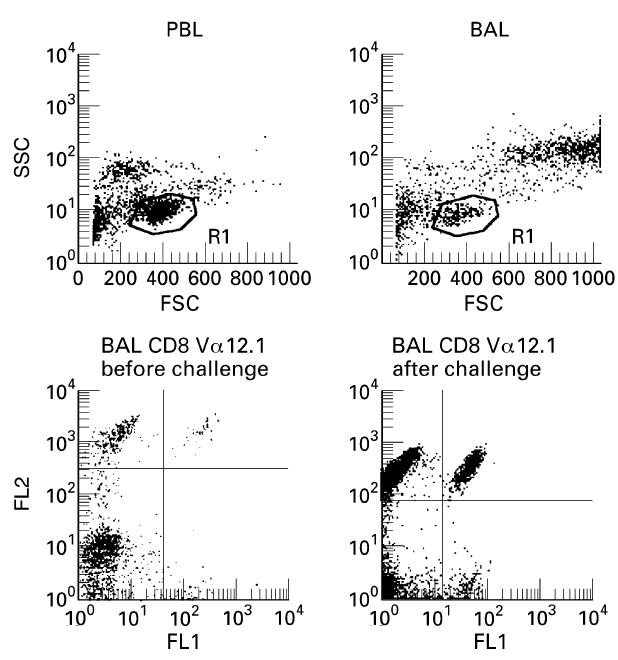

In the BAL CD4+subset, by contrast, the picture was more complex. One disappearing and two emerging expansions were recorded, although one of the latter was minor. There were also three remaining expansions (Table 6). Comparing the lung T cell subsets, there was a significantly higher increase in the number of expansions in BAL CD8+than in BAL CD4+after allergen challenge (P < 0.01 including hidden expansions; P < 0.05 excluding hidden expansions).

Table 6.

Overview of T cell expansions

In the PBL CD8+subset, three minor expansions were present before challenge. One of these remained and no new expansions emerged after challenge. As mentioned earlier, no expansions before or after challenge were recorded in the PBL CD4+cells. A comparison of BAL and peripheral blood cells demonstrates that in BAL CD4+, the number of expansions was significantly higher than in PBL CD4+already before challenge (P < 0.05). In BAL CD8+, the number of expansions became significantly higher than in PBL CD8+after challenge (P < 0.01). An overview of all expansions is depicted in Table 6 and in Fig. 2. There was no preference for any particular TCR V segment. Before as well as after challenge, expansions > 15% were only recorded in the lung cells, and expansions > 20% only in the BAL CD8+cells. There were no expansions of T cells using the same V gene segment in BAL CD8+and PBL CD8+, nor were there any expansions of the same Vα or Vβ in both BAL CD8+and BAL CD4+.

Fig. 2.

Lung T cell expansions in different cell populations before (▪) and after allergen challenge (□). Expansions are marked by an asterisk. (a) Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) CD8. (b) BAL CD4.

Taking into account not only expansions but the TCR V MoAb reactivities of the entire antibody panel, the most pronounced changes in TCR V gene segment usage occurred in the BAL compartment, as determined by delta value calculation. The mean change in TCR Vα/Vβ MoAb reactivity in BAL CD8+was 1.6%, compared with 1.0% in BAL CD4+ (NS), being significantly higher than in PBL CD8+(0.7%, P < 0.001) and PBL CD4+(0.4%, P < 0.001). Furthermore, the changes in BAL CD4+were larger than in PBL CD4+(P < 0.001). These results are in agreement with data from calculating the number of expansions.

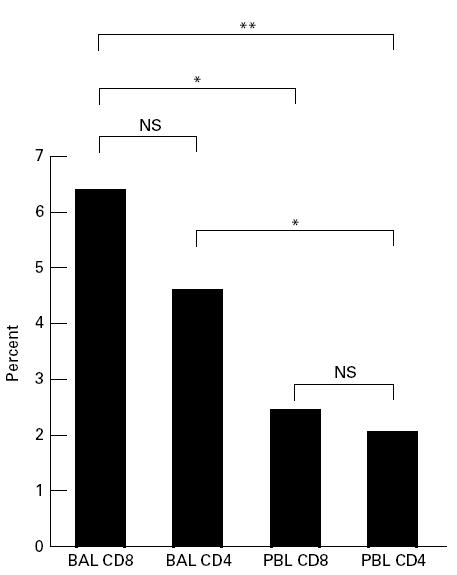

An analysis of total antibody panel coverage before and after challenge was performed, also demonstrating that from this aspect the largest changes took place in the BAL cells (Fig. 3). In BAL CD8+, the mean change in panel coverage was 6.4%, compared with 4.6% in BAL CD4+(NS), 2.4% in PBL CD8+(P < 0.05) and 2.0% in PBL CD4+(P < 0.01). The change in BAL CD4+was also significantly higher than in PBL CD4+(P < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Mean absolute change in antibody panel coverage before and after challenge. Only Vα and Vβ segments analysed on both occasions are included. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. BAL, Bronchoalveolar lavage; PBL, peripheral blood lymphocytes.

To determine how much the lung T cell repertoire mirrored that of blood, delta values using the differences in each MoAb reactivity between PBL CD4+and BAL CD4+subsets, as well as between PBL CD8+and BAL CD8+cells, were calculated before and after challenge. In the CD8+cells, the mean delta value PBL-BAL before challenge was 1.5% versus 2.2% after challenge (P < 0.05). For the CD4+cells the corresponding values were 1.6% and 1.5%, respectively (NS). This may be compared with the mean TCR V MoAb reactivities (reflecting the usage of an ‘average’ TCR V gene segment), which before challenge were in the interval of 3.1–4.5% for the four different subsets.

Rechallenge

Three of the patients were rechallenged with the same allergen 10 months after the first analysis. The T cell expansions that emerged subsequent to the first allergen exposure had in all cases now disappeared. Moreover, the same T cell expansions were not possible to stimulate again at this second allergen challenge. Instead, one of the patients developed a new expansion (patient 4; BAL CD8+ Vβ5.1 = 2.8% before challenge and 15.9% after challenge).

The delta values for mean change in TCR V gene segment expression were similar to those after the first provocation (data not shown).

HLA typing

The result of the typing for HLA class I and class II is included in Table 1. There was a tendency for HLA-DR3(17) and DR4 to be over-represented, and for DR1, DR6(13) and DR7 to be under-represented. It was noted that the patients (numbers 3, 5, 6 and 8) with the least change in BAL CD4/CD8 ratio before and after challenge, and in terms of T cell expansions, were all HLA-A3+.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we have concentrated on analysing changes in the lung and blood TCR repertoires before and after allergen exposure of individuals with allergic asthma. The most prominent changes occurred in the BAL CD8+subset, in which large T cell populations using particular Vα or Vβ TCR gene segment products frequently appeared after challenge. In addition to recording T cell expansions we analysed changes in TCR V gene segment usage in different cell populations through calculations of delta values, as well as determinations of changes in total antibody panel coverage before and after challenge. The latter two methods also demonstrated a tendency for the largest changes in TCR usage to occur in the BAL CD8 subset. Interestingly, however, there was already a high frequency of BAL CD4+expansions before challenge.

Our criteria for identifying T cell expansions are based on the TCR repertoire in PBL of healthy blood donors [10], since acquisition of flow cytometric data regarding the normal BAL TCR repertoire is hampered by the limited number of lymphocytes retrievable from a healthy lung. We have used these criteria from PBL also for BAL cells, since the focus of this study was on investigating changes in the TCR repertoires before and after allergen challenge, and not on comparing TCR V segment frequencies in lung and peripheral blood. Furthermore, the application of the same limits for expansions also to BAL cells is justified by other studies, employing the PCR technique, demonstrating a similar TCR V gene usage in PBL and BAL of healthy individuals [16–18]. The present study of asthma patients also revealed a basically similar TCR Vα/Vβ usage among PBL and BAL lymphocytes, with the notable exceptions of T cell expansions.

An important issue is whether the lung-limited T cell expansions developed as a consequence of recruitment from the blood and/or lymphatic tissue, or alternatively from a local proliferation. A recent study demonstrating the accumulation of oligoclonal populations of T cells in the lungs of asthma patients following allergen challenge [19] suggested a recruitment from the blood in the early phase of the response to allergen inhalation. The time of sampling is probably important for determining the relative contribution of lymphocyte recruitment versus local proliferation. In the present study we chose to analyse the BAL T cells 4 days after bronchoprovocation to include those cells that locally proliferate in response to the allergen.

An expansion of T cells using a particular Vα or Vβ gene segment may arise in response to a conventional antigenic peptide presented in the peptide-binding groove of an MHC molecule. Examples of antigen sources include pathogens and allergens [20] or autoantigens such as heat shock proteins [21]. An alternative type of antigen, so called superantigens, bind to particular TCR Vβ chains outside the antigen-binding cleft [22]. A superantigen may cause a dramatic proliferation of T cells both in the CD4+and CD8+subsets, the stimulated cells having only a certain Vβ in common. A superantigen does not seem likely to have caused the T cell perturbations recorded in the present study, since the expansions used different Vβ gene segments, as well as Vα segments, and were never observed in the CD4+and CD8+subsets simultaneously. The finding of different TCR V expansions, though all but one of the subjects were challenged with cat allergen, is not surprising, since the MHC haplotypes differed between the patients, and it is well known that allergens usually contain multiple epitopes [23]. An intriguing question is why the most prominent changes following allergen inhalation occurred in the CD8+cell subset. Exogenous antigens may be anticipated to interact primarily with CD4+T cells, but the possibility for such antigens to gain access to the MHC class I processing pathway with subsequent presentation to CD8+cells has been demonstrated [24] and both subsets are involved in the murine response to inhaled soluble protein antigens [25]. Alternatively, CD8+expansions may represent regulatory T cells specific for TCR epitopes presented by allergen-reactive CD4+T cells, similar to the classical idiotype–anti-idiotype-specific B cell network proposed by Jerne [26].

Our finding of a tendency towards increased relative numbers of CD8+T cells in BAL is in agreement with an earlier study reporting an increase in BAL CD8+cells in those asthmatic subjects who only develop an early response after challenge [27]. When BAL without prior allergen challenge was performed in asthmatic subjects, the highest numbers of CD8+cells were apparent in the subjects with milder asthma [28]. CD8+cells may thus have a suppressive role in asthma. In contrast, CD8+T cells in the mouse were recently demonstrated to have a crucial role in the development of airway hyperresponsiveness and eosinophil infiltration [29]. We recently reported that in extrinsic allergic alveolitis there are frequently dramatic CD8+T cell expansions restricted to the lung that normalize with clinical improvement [30]. The functional role of the expanded T cells in asthma can not be judged from our data. One way of approaching T cell function is to investigate their cytokine production. In allergen-sensitized mice, T cell subsets expressing certain Vβs were found to regulate IgE production, by exhibiting different cytokine production patterns [31]. Transfer of a specific Vβ+T cell subset also increased airway responsiveness in the recipients [32].

That the T cell expansions occurring after the first challenge could not be repeated is an intriguing finding, with several possible explanations. One homeostatic mechanism for controlling the size of antigen-stimulated clones is a form of apoptosis termed activation-induced cell death (AICD), which occurs as a result of repeated antigenic stimulation [33]. In contrast, anergy (for review see [34]) is a state in which a lymphocyte is alive but fails to proliferate when stimulated with antigen. An expansion of T cells followed by apoptosis and an anergic state of the remaining cells may be plausible, since clonal anergy in vivo may be preceded by a transient proliferation [35]. Due to a remaining capacity to produce cytokines, however, the anergic T cells may still play functional roles even if the size of the clone is limited. Redistribution of T cells to other compartments is likely after clearance of allergen from the lungs, but this does not explain why the expansions cannot be reproduced upon the second challenge.

The persisting PBL CD8+expansions in two of the patients (one recorded at 3/4 sample time points) are not surprising, since in CD8+peripheral blood lymphocytes, clonal expansions stable over time have been recorded in apparently healthy individuals [10,36,37]. The functional significance of such T cell expansions is still not clear. The increased frequency of BAL CD4+T cell expansions noted before allergen challenge is more intriguing and may be related to the asthma disease.

No correlations could be made between the tendency to develop BAL T cell expansions and clinical characteristics, such as parameters of allergen bronchoprovocation or differentials of PBL and BAL cells. There was a tendency towards less prominent increases in total cell concentration in BAL after challenge in those patients with no BAL CD8+expansions. However, significant differences with respect to these parameters may be observed only in a larger patient group.

The study of the lung T cell response may have implications for future therapies targeting T cells. In immunotherapy, tolerance is induced by application of increasing doses of allergen, a major disadvantage being the risk for an anaphylactic reaction [38]. Since a single peptide can induce tolerance to the entire protein [39] without the risk of anaphylaxis, peptide-based therapy is an attractive alternative. In vitro studies of T cell proliferation to different epitopes, in combination with investigations of the in vivo lung T cell response to allergen challenge, should help identify critical epitopes and T cells, and thus provide a better basis for a rational design of vaccines for the modulation of the immune response in allergic patients.

In conclusion, we have in this study investigated the TCR V gene usage of PBL and BAL lymphocytes before and after inhalation challenge with allergen. The finding of an increased number of lung-limited CD8+T cell expansions, some of them dramatic, suggests a specific antigen-related response. The frequency of BAL CD4+expansions was moderately increased already before challenge. These findings direct attention to the role of T lymphocytes in the pathogenesis of allergic asthma.

Acknowledgments

The excellent technical assistance of Berit Olsson, Margitha Dahl and Marie Hallgren is highly appreciated. We thank Dr R. A. Harris for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation, the Karolinska Institute, the Swedish Council for Work Life Research (project no. 91-0223), the Swedish Foundation for Health Care Sciences and Allergy Research (project no. A95 083) and Clas Groschinsky's Foundation.

References

- 1.Djukanovic R, Roche W, Wilson J, et al. Mucosal inflammation in asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142:434–57. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.2.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kay A. Asthma and inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1991;87:893–910. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(91)90408-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson J, Djukanovic R, Howarth P, Holgate S. Lymphocyte activation in bronchoalveolar lavage and peripheral blood in atopic asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:958–60. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.4_Pt_1.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azzawi M, Bradley B, Jeffery P, et al. Identification of activated T lymphocytes and eosinophils in bronchial biopsies in stable atopic asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142:1407–13. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.6_Pt_1.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradley B, Azzawi M, Jacobson M, et al. Eosinophils. T-lymphocytes, mast cells, neutrophils and macrophages in bronchial biopsy specimens from atopic subjects with asthma: comparison with biopsy specimens from atopic subjects without asthma and normal control subjects and relationship to bronchial hyperresponsiveness. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1991;88:661–74. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(91)90160-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson J, Djukanovic R, Howarth P, Holgate S. Inhaled beclomethasone dipropionate downregulates airway lymphocyte activation in atopic asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:86–90. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.1.8111605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moss P, Rosenberg W, Bell J. The human T cell receptor in health and disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 1992;10:71–96. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.000443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis M, Bjorkman P. T-cell antigen receptor genes and T-cell recognition. Nature. 1988;334:395–402. doi: 10.1038/334395a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arden B, Clark S, Kabelitz D, Mak T. Human T-cell receptor variable gene segment families. Immunogenetics. 1995;42:455–500. doi: 10.1007/BF00172176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grunewald J, Wigzell H. T cell expansions in healthy individuals. Immunologist. 1996;4:99–103. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dahlén B, Zetterström O, Björck T, Dahlén S-E. The leukotriene-antagonist ICI-204,219 inhibits the early airway reaction to cumulative bronchial challenge with allergen in atopic asthmatics. Eur Resp J. 1994;7:324–31. doi: 10.1183/09031936.94.07020324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eklund A, Blaschke E. Relationship between changed alveolar-capillary permeability and angiotensin converting enzyme activity in serum in sarcoidosis. Thorax. 1986;41:629–34. doi: 10.1136/thx.41.8.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grunewald J, Olerup O, Persson U, Öhrn M, Wigzell H, Eklund A. T cell receptor variable gene usage by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and peripheral blood of sarcoidosis patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4965–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gulwani-Akolkar B, Posnett D, Janson C, et al. T cell receptor V-segment frequencies in peripheral blood T cells correlate with human leukocyte antigen type. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1139–46. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.5.1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olerup O, Zetterquist H. HLA-DR typing by PCR amplification with sequence-specific primers (PCR-SSP) in 2 hours: an alternative to serological DR typing in clinical practice including donor-recipient matching in cadaveric transplantation. Tissue Antigens. 1992;39:225–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1992.tb01940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forman J, Klein J, Silver R, Liu M, Greenlee B, Moller D. Selective activation and accumulation of oligoclonal Vβ-specific T cells in active pulmonary sarcoidosis. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:1533–42. doi: 10.1172/JCI117494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yurovsky V, Bleecker E, White B. Restricted T-cell antigen receptor repertoire in bronchoalveolar T cells from normal humans. Human Immunol. 1996;50:22–37. doi: 10.1016/0198-8859(96)00126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burastero S, Borgonovo B, Gaffi D, et al. The repertoire of T-lymphocytes recovered by bronchoalveolar lavage from healthy nonsmokers. Eur Respir J. 1996;9:319–27. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09020319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burastero S, Crimi E, Balbo A, et al. Oligoclonality of lung T lymphocytes following exposure to allergen in asthma. J Immunol. 1995;155:5836–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boitel B, Ermonval M, Panina-Bordignon P, Mariuzza R, Lanzavecchia A, Acuto O. Preferential Vβ gene usage and lack of junctional sequence conservation among human T cell receptors specific for a tetanus toxin-derived peptide: evidence for a dominant role of a germline-encoded V region in antigen/major histocompatibility complex recognition. J Exp Med. 1992;175:765–77. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.3.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaufmann S. Heat shock proteins and the immune response. Immunol Today. 1990;11:129–36. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(90)90050-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ulrich R, Bavari S, Olson M. Bacterial superantigens in human disease: structure, function and diversity. Trends Microbiol. 1995;3:463–8. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)89011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Neerven R, Ebner C, Yssel H, Kapsenberg M, Lamb J. T-cell responses to allergens: epitope-specificity and clinical relevance. Immunol Today. 1996;17:526–32. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)10058-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lanzavecchia A. Mechanisms of antigen uptake for presentation. Curr Opin Immunol. 1996;8:348–54. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McMenamin C, Holt P. The natural immune response to inhaled soluble protein antigens involves MHC class I-restricted CD8+ T-cell mediated but MHC class II-restricted CD4+ T-cell-dependent immune deviation resulting in suppression of IgE production. J Exp Med. 1993;178:889–99. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.3.889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jerne N. Toward a network theory of the immune system. Ann Immunol. 1974;125C:373–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gonzales M, Diaz P, Galleguillos F, Ancic P, Cromwell O, Kay A. Allergen-induced recruitment of bronchoalveolar helper (OKT4) and suppressor (OKT8) T-cells in asthma: relative increases in OKT8 cells in single early responders compared with those in late-phase responders. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;136:600–4. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/136.3.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelly C, Stenton S, Ward C, Bird G, Hendrick D, Walters E. Lymphocyte subsets in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid obtained from stable asthmatics, and their correlations with bronchial responsiveness. Clin Exp Allergy. 1989;19:169–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1989.tb02360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamelmann E, Oshiba A, Paluh J, et al. Requirement for CD8+ T cells in the development of airway hyperresponsiveness in a murine model of airway sensitization. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1719–29. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wahlström J, Berlin M, Lundgren R, et al. Lung and blood T-cell receptor repertoire in extrinsic allergic alveolitis. Eur Respir J. 1997;10:772–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Renz H, Bradley K, Gelfand E. Production of interleukin-4 and interferon-γ by TCR-Vβ-expressing T-cell subsets in allergen-sensitized mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1996;14:36–43. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.14.1.8534484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Renz H, Saloga J, Bradley K, et al. Specific Vβ T cell subsets mediate the immediate hypersensitivity response to ragweed allergen. J Immunol. 1993;151:1907–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parijs L, Ibraghimov A, Abbas A. The roles of costimulation and Fas in T cell apoptosis and peripheral tolerance. Immunity. 1996;4:321–8. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80440-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwartz R. Models of T-cell anergy: is there a common molecular mechanism? J Exp Med. 1996;184:1–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kearney E, Pape K, Loh D, Jenkins M. Visualization of peptide-specific T-cell immunity and peripheral tolerance induction in vivo. Immunity. 1994;1:327–39. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90084-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Posnett D, Sinha R, Kabak S, Russo C. Clonal populations of T cells in normal elderly humans: the T cell equivalent to ‘Benign Monoclonal Gammapathy’. J Exp Med. 1994;179:609–18. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grunewald J, Tehrani M, Andersson R, DerSimonian H, Wigzell H. A persistent monoclonal T cell expansion in the peripheral blood of a normal adult male: a new clinical entity? Clin Exp Immunol. 1992;89:279–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb06945.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stewart G, Lockey R. Systemic reactions from allergen immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1992;90:567–78. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(92)90129-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoyne G, O'Hehir R, Wraith D, Thomas W, Lamb J. Inhibition of T cell and antibody responses to the house dust mite allergen by inhalation of the dominant T cell epitope in naive and sensitized mice. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1783–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.5.1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]