Abstract

IL-10 is a cytokine which not only suppresses cellular immunity but also stimulates the humoral response. In certain animal models of autoimmunity, IL-10 exerts a protective effect against auto-destruction. This study was to ascertain whether there could be a role for IL-10 in human autoimmune thyroid disease. Total RNA was extracted from snap-frozen thyroid blocks from surgical specimens. Five ‘normal’, five multinodular, six Graves and two Hashimoto thyroids (one euthyroid and one hypothyroid) were studied. Approximately 7 μg of total RNA from each gland were reverse transcribed with oligo-dT primers. Pre-plateau semiquantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed with specific IL-10 primers. PCR products were run on a 1.5% agarose gel, blotted onto a N-hybond nylon membrane, hybridized with a specific internal probe labelled with γ-32P-ATP and autoradiographed. Statistical analysis of densitometric values showed significantly higher IL-10 levels in the autoimmune than in the non-autoimmune glands. In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry showed that the IL-10 message was located within the infiltrating lymphomononuclear cells. Histological analysis revealed that the autoimmune thyroids with the highest IL-10 levels were characterized by relevant degrees of B and T cell infiltration and also exhibited the greatest percentage of spontaneous HLA class II expression on thyrocytes. IL-10 and neutralizing anti-IL-10 antibodies were not able to regulate in vitro spontaneous or interferon-gamma (IFN-γ)/phytohaemagglutinin (PHA)-induced HLA class II on thyrocytes. We conclude that in active autoimmune thyroiditis, in addition to the well documented production of Th1 cytokines, Th2-related lymphokines can be detected simultaneously. It can be envisaged that in this condition the role of IL-10 might be directed to the stimulation of B cell proliferation and antibody production rather than to the suppression of proinflammatory cytokine release.

Keywords: IL-10, thyroid autoimmune disease, Hashimoto's disease, Graves' disease, Th1 and Th2 cytokines

INTRODUCTION

IL-10 is a cytokine that both suppresses cell-mediated immunity and stimulates the humoral immune response [1,2]. Primarily secreted by CD4+ lymphocytes, IL-10 can also be produced by monocytes/macrophages, B cells and CD8+ cells [3–8]. Human IL-10 interferes with cellular immunity in several fashions: it inhibits not only the secretion of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) by T cells in the presence of macrophage/monocytes [9], but also the synthesis of the inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-2, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), IL-6, IL-8 and IFN-γ by lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated monocytes/macrophages [5,10–13]. IL-10 suppresses both spontaneous and IFN-γ-induced HLA class II expression by antigen-presenting cells (APC) [14], decreasing their ability to present antigen. Simultaneously, it stimulates the B lymphocyte response by enhancing HLA class II expression on B cells [15] and stimulating B cell proliferation [16]. There is evidence from certain animal models of parasitosis and in some human chronic infections that increased IL-10 secretion is associated with a poor prognosis [17,18]. In contrast to infectious diseases, in experimental models of autoimmunity IL-10 appears to exert protective rather than harmful effects: (i) high IL-10 levels in murine myelin-induced encephalitis (EAE) are associated with clinical remission of the disease [19,20]; (ii) in vivo administration of IL-10 in rodents with experimental autoimmune thyroiditis succeeds in preventing and reducing the severity of the disease [21]; (iii) in vivo systemic administration of recombinant IL-10 in non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice prevents the onset of diabetes [22,23], although the picture becomes less clear when IL-10 is expressed locally [24].

It has been shown that in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), IL-10 is spontaneously produced by monocytes and T cells within the synovial membrane lining layer and is found to be functionally relevant. Neutralization of endogenously secreted IL-10 results in a considerable increase in the protein levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β [25,26]. These findings have raised the possibility of a therapeutic use for IL-10 in human autoimmunity [26].

Human thyroid autoimmune disease encompasses a particularly broad spectrum of clinical and immunological features, ranging from predominantly humoral stimulatory to destructive cellular responses. The purpose of this study was to ascertain a possible role for IL-10 in the development of this disease and/or its treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Thyroid specimens

The thyroids studied were: five ‘normal’ thyroids (nos 1–5) obtained from laryngectomies for carcinoma of the larynx (Royal ENT Hospital, London, UK); five thyroids from patients with multinodular goitre (nos 6–10); five thyroids from patients with Graves' disease (GD) (nos 11–16); and two thyroids derived from patients suffering with Hashimoto's thyroiditis (nos 17–18) (Royal London Hospital, London, UK). In the group with thyroid autoimmune disease, six were female and two male with an age range of 28–42 years. The duration of their disease was between 2 years (no. 14) and 6 years (no. 17). One patient (no. 15) also had recent onset of insulin-dependent diabetes. Diagnosis was made by conventional clinical and laboratory criteria. All patients with autoimmune thyroid disease had circulating thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibodies with titres ranging from 202 to 3202, but thyroglobulin (Tg) antibodies were detected only in patients' sera nos 16 (402) and 17 (402). Histology confirmed the clinical diagnosis in all cases. Surgery was performed because anti-thyroid drugs (at least two courses of carbimazole or PCU treatment for not less than 6 months) failed to put patients with GD in remission or because a large goitre produced an intense local discomfort. Thyroids had to be excised during laryngectomies because of technical reasons. Thyroid no. 14 was excised because radioactive treatment could have exacerbated the patient's exophthalmos. Radioactive treatment was attempted for thyroid no. 13, but failed to put the gland at rest.

Total RNA extraction

Snap-frozen thyroid tissue blocks were manually macerated in an homogenizer filled with liquid nitrogen and surrounded by dry ice. Total RNAs were extracted by guanidine isothyocianate (RNAzol B) (Biogenesis, Poole, UK) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The concentrations were determined by the optical density (OD) at 260 nm and the quality assessed by electrophoresis through 1.5% agarose (Sigma, Poole, UK). The 28S and 18S bands were visualized by UV light after staining with ethidium bromide. The RNAs were stored under 70% ethanol at −70°C.

Reverse transcription

Approximately 7 μg of each RNA were used for reverse transcription by oligo dT priming using a cDNA cycle kit (Invitrogen, Abingdon, UK). The quality of the cDNA was assessed by electrophoresis through 1.5% agarose.

Polymerase chain reaction

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-mediated amplification was carried out on the cDNAs within 10 days of preparation. Specific forward and reverse IL-10 primers were prepared (King's College Hospital Medical School, London, UK) at a concentration of 0.9 μg/μl (IL-10 primers, 5′-ATGCCCCAAGCTGAGAACCAA GACCCA; 5′-TCTCAAGGGGCTGGGTCAGCTATCCCA). PCR was performed in standard PCR buffer as supplied by the manufacturer, containing 1.5 mm MgCl2, 0.25 mm dNTPs and 0.5 U Taq polymerase (Perkin Elmer, Warrington, UK) in a 75-μl reaction mixture with 5 μl cDNA and 2 μl of IL-10 primer using a thermal cycler (Perkin Elmer Cetus, Emeryville, CA). Pre-plateau levels of PCR products were first established over 15–20–25–30–35 cycles. Each cycle consisted of 94°C for 30 s, 64°C for 1 min and 72°C for 1 min. All 18 samples were run simultaneously for 30 cycles as pre-plateau levels of PCR products were consistently determined at these conditions.

Quantification of IL-10

Twenty microlitres of each PCR product were separated on a 1.5% agarose gel and blotted onto Hybond N+ nylon membrane (Amersham, Aylesbury, UK), using NaOH as transfer agent. The membrane was hybridized with a specific IL-10 internal oligonucleotide probe (IL-10 probe, 5′-GCAGGTGAAGAATGCCTTTA) labelled with γ-32P-ATP polynucleotide kinase (Amersham) and subjected to autoradiography. Developed films were quantified by densitometry (Beckman (Fullerton, CA) densitometer array). A value of 100% was ascribed to the densest sample. Levels found in the remaining thyroids were given as a percentage of this value.

In situ hybridization

Cryostat sections (8 μm) were cut and applied onto polysine coated slides (BDH, Poole, UK). The sections were air-dried for 15 min, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde PBS/DEPC (Sigma) for 5 min, washed three times in PBS/DEPC for a total of 15 min, and incubated overnight at 50°C with the hybridization mixture (HMIX) containing 57 μl formamide (Sigma), 20 μl 20 × SSC, 20 μl 50% (w/v) dextran sulphate (Pharmacia Biotech, St Albans, UK), 1 μl 100 × Denhardt's solution consisting of 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma), 2% Ficoll (Pharmacia), and 2% polyvinyl pyrollidone (Sigma). Digoxigenin-labelled IL-10 probe (2 μl) consisting of a cocktail of four IL-10 oligonucleotides (R&D, Abingdon, UK) was added to 100 μl of the above hybridization mixture to a final probe concentration of 2 ng/100 μl. As positive controls, cytosmears from a mouse cell line transfected with rhIL-10 (a gift from Dr M. G. Roncarolo, DNAX, Palo Alto, CA) were used. Negative control slides were incubated with (i) HMIX alone, (ii) with RNase A (10 μg/ml; Sigma) 2 × SSC for 2 h at 37°C before incubation with HMIX alone or with the IL-10 probe. Three washing steps were carried out with 50% formamide/2 × SSC for 12 min at 54°C, 2 × SSC for 12 min at 54°C, 2 × SSC for 12 min at room temperature followed by a final step with a blocking solution containing Tris-buffered saline (TBS) which consisted of 1 m Tris–HCl buffer pH 7.4, 1% Triton 100, 1% BSA (Sigma). The hybridization was visualized by a sheep anti-digoxigenin IgG-Fab fragment alkaline phosphatase-conjugated (1:100 dilution) (Boeringer Mannheim, Lewes, UK) for 2 h at room temperature. The staining was carried out with the NBT/BCIP (Sigma) chromogen.

Immunohistochemistry

In vivo expression of IL-10 on thyroid sections

Sections from thyroids 13–18 and 1–4 were stained for 45 min with a rat MoAb to human IL-10 (IgG2a) and a rat IgG2a isotype control (both at dilution 1:5) (Cambridge Bioscience, Cambridge, MA) followed by FITC-labelled rabbit anti-rat immunoglobulin (dilution 1:10) (Dako Ltd, High Wycombe, UK). Fluorescence was evaluated in duplicate preparations by two independent readers on a Zeiss type III microscope equipped with epi-illumination.

In vivo expression of immune parameters on thyroid sections

In vivo expression of immune parameters was also studied on 4-μm cryostat sections from thyroids nos 13–18 derived from patients with thyroid autoimmunity. In addition to the HLA class II MoAb the following MoAb reagents were used for staining: UCHT1 (Pan T) (Professor P. Beverley, London, UK); CD20 (Pan B) and CD25 (activated T cells) (Dako); P11 (specific for mouse thyroglobulin; Professor P. Lydyard, London, UK). Scoring was performed blindly by two independent readers for (i) number of infiltrates per section; and (ii) size of infiltrates. The number of infiltrates per section was counted and scored as follows: < 2, −; 2–5, +; 6–10, + +; > 10, + + +. When sections were characterized mostly by a thick sheet of inflammatory cells the score was recorded as + + + +. The size of the infiltrate was scored on 1-mm2 grids (Graticules Ltd, Tunbridge, UK), as follows: < 1 mm2 infiltrate, −; 1–3 mm2 infiltrate, +; 3–6 mm2 infiltrate, + +; 6–8 mm2 infiltrate, + + +; sheet of dense cells, + + + +.

For statistical analysis each cross was given a value of 1 and of 0.5 of intermediate values.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using the program GB-Stat 3.0. Groups were compared by Mann–Whitney U-analysis (MWU) unless the distribution of values was normal, in which case Student's test was applied.

In vitro expression of HLA molecules on thyrocytes in basal conditions and after treatment

Thyroid cell preparations were stained by immunofluorescence on glass coverslips (Life Technologies, Poole, UK) for spontaneous HLA class II expression (using Mid 3 MoAb; Professor P. Lydyard) on thyrocytes after 48 h in culture as previously described [27]. After fixing with acid/alcohol mixture for 10 min, slides were mounted in a glycerol-based mounting medium (Vector, Peterborough, UK). Fluorescence was evaluated in duplicate, counting a minimum of 300 cells per preparation.

In addition, the direct effect of IL-10 and that mediated by IFN-γ or phytohaemagglutinin (PHA) on HLA class II molecules on thyrocytes were investigated. In parallel sets of experiments the effects of anti-IL-10 neutralizing antibody on HLA class II expression on thyrocytes was also evaluated in basal conditions and after IFN-γ or PHA stimulation. All experiments were performed in duplicates. In brief, thyroid cell aliquots from three GD and one multinodular goitre patients were plated onto 24-well plates (Life Technologies) at the concentration of 2 × 105 cells/well in RPMI and 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). After cell adherence (24–36 h), cells were extensively washed and fresh medium supplemented with 1% FCS was added together with the following combinations of treatments: (i) rhIL-10 in combination with IFN-γ for 3 and 6 days or with PHA for 3 and 5 days; (ii) rhIL-10 for 24–48 h before the addition of either IFN-γ for 3 and 6 days or PHA for 3 and 5 days; (iii) rhIL-10 (alone) (4–100 μg/ml) (Genzyme, Cambridge, MA) for 3–7 days; IFN-γ (alone) (200–500 U/ml) (Genzyme) added at day 3 for 3 and 6 days; PHA (alone) (2.5 μg/ml) (Sigma) added at days 1–3 for 3 and 5 days, respectively; (iv) anti-IL-10 neutralizing antibody (IgG2b) (5–100 mg/ml) (R&D) and a MoAb of the IgG2b isotype (Pharmingen) at the same concentration were incubated either alone, before or together with IFN-γ or PHA, following exactly the same protocol to that described for rhIL-10.

After extensive washing, cells were subsequently detached with trypsin-EDTA (Life Technologies) and stained with 20 μl HLA class II PE-conjugated MoAb (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA). The stained samples were then acquired onto a FACScan flow cytometer and analysed using LYSIS II software (Becton Dickinson). A gate was set to exclude debris. At least 2000 cells per sample were acquired and FL-2 was recorded in a Hewlett Packard computer along with forward scatter and side scatter.

RESULTS

Reverse transcription-PCR

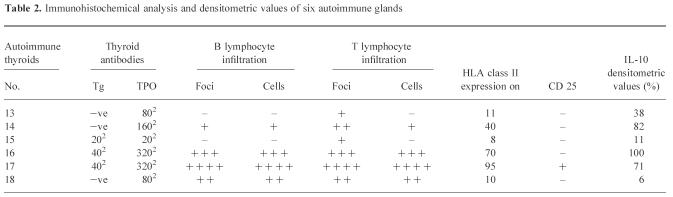

Southern blotting with a specific IL-10 probe (5′-GCAGGTGAA GAATGCCTT) revealed the presence of the 352-bp IL-10 band in samples from all patients with multinodular goitre and autoimmune thyroid disease, but only in 3/5 ‘normal’ control thyroids (Fig. 1). IL-10 bands were more intense in autoimmune samples (thyroids no. 11–18) than in ‘normal’ or multinodular thyroids (nos 1–10). Three autoimmune thyroids had particularly strong bands: nos 14 and 16 (GD) and no. 17 (Hashimoto's). A very weak band was observed in thyroid no. 18, an end-stage fibrous Hashimoto's gland.

Fig. 1.

IL-10 mRNA expression by ‘normal’ thyroids (HT1–5), multinodular goitre (HT6–10), Graves’ disease thyroids (HT11–16), Hashimoto's thyroids (HT17–18). Lanes show the polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-amplified product of RNA from the indicated thyroids as described in Materials and Methods. Products were visualized by hybridization using an internal IL-10 cDNA probe and analysed by autoradiography. Products of the predicted size (352 bp) were identified with variable intensity.

Densitometric analysis and statistical evaluation

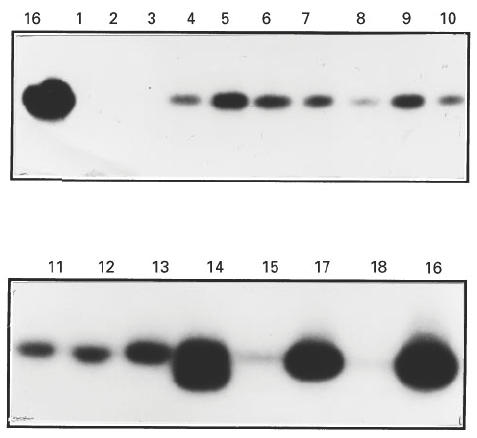

The highest value was obtained with thyroid no. 16, which was ascribed a value of 100. Levels found in the remaining thyroids are presented as percentages of thyroid no. 16 (Table 1). Statistical analysis revealed significantly higher IL-10 levels in the autoimmune thyroids as a whole than in non-autoimmune glands (P = 0.01, MWU) (Fig. 2a, b) as well as in the autoimmune versus‘normal’ (P = 0.0404, MWU) and autoimmune versus multinodular (P = 0.0332, t-test). Furthermore, the GD thyroids as a group had significantly elevated IL-10 levels compared with normal glands (P = 0.0087, t-test) (Fig. 2c), with a tendency to significance compared with multinodular glands alone (P = 0.0652). No difference was found between normal and multinodular values.

Table 1.

Densitometric analysis of IL-10 levels, expressed as percentage of value of thyroid no. 16

Autoradiograms were scored by densitometry as described in Materials and Methods. The highest score obtained (thyroid no. 16) was ascribed a value of 100. Levels found in the remaining thyroids are given as the percentage of thyroid no. 16.

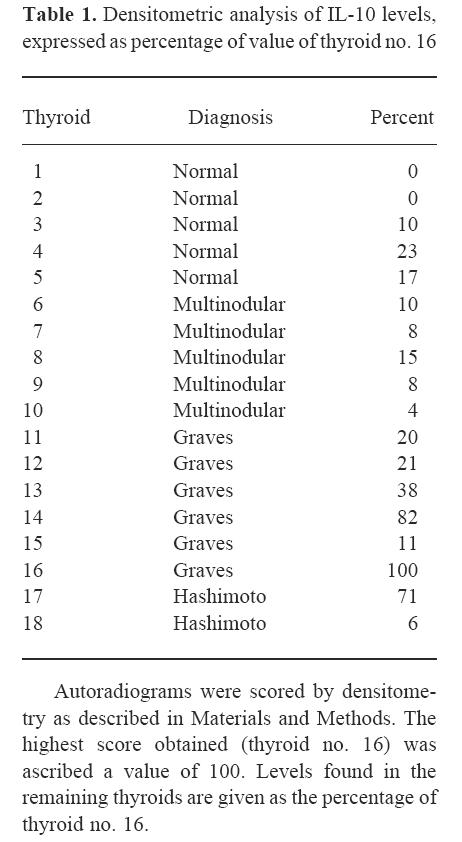

Fig. 2.

IL-10 levels of expression in non-autoimmune and autoimmune thyroids: statistical evaluation. (a) IL-10 levels of expression in non-autoimmune and autoimmune thyroids (mean values of the densitometric evaluation for each group of patients). (b) Statistical evaluation showed significantly higher IL-10 levels in the autoimmune thyroids as a whole compared with non-autoimmune glands: P = 0.01 (Mann–Whitney U-analysis (MWU)). (c) Graves’ thyroids, as a group, expressed significantly elevated IL-10 levels compared with normal glands: P = 0.0087.

In situ hybridization

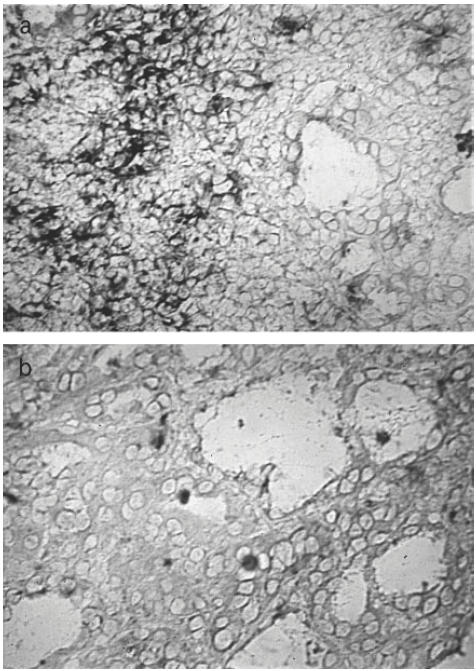

In the IL-10-transfected positive control cytosmears a clear IL-10 signal was detected in the cytoplasm of the transfected cells. IL-10 message was expressed in the thyroid sections within the lymphomononuclear cells of the most infiltrated areas with a patchy distribution. The signal was particularly evident in the autoimmune thyroids expressing high IL-10 levels by PCR (38% and above) (Fig. 3a). The epithelial follicular cells did not clearly show IL-10 expression, although occasionally thyrocytes appeared to be weakly stained in proximity to the infiltrated areas. RNase treatment abolished the IL-10 staining (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Localization of IL-10 mRNA in Hashimoto's thyroiditis. Sections (8 μm) were hybridized with a digoxigenin-labelled IL-10 probe with or without preincubation with RNase as described in Materials and Methods. The hybridization signal was localized: (a) within the lymphomononuclear cells of the most infiltrated areas. Thyrocytes did not show a clear message; (b) the signal disappeared when the sections were pretreated with RNase.

Immunocytochemistry

In vivo expression of IL-10 on thyrocytes

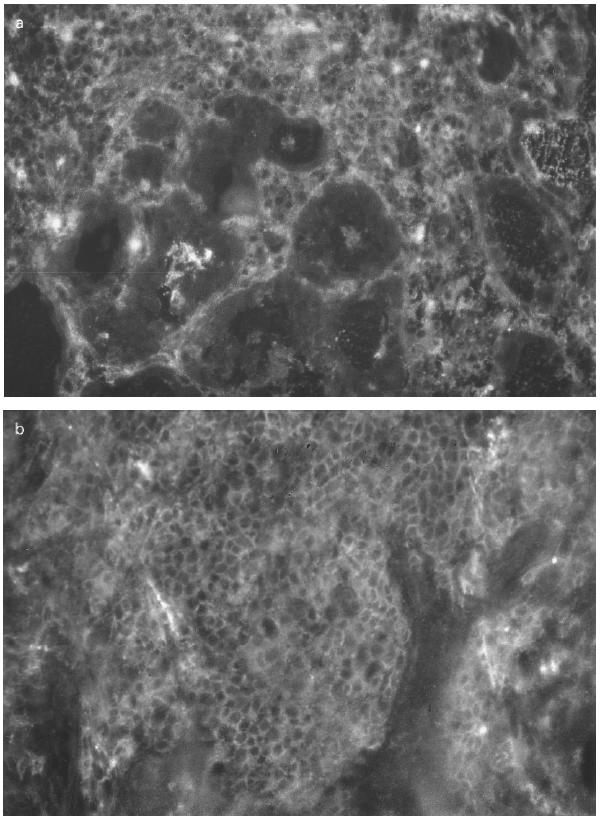

Anti-IL-10 MoAb stained lymphomononuclear cells within the infiltrates, particularly in the two Hashimoto's preparations, but also occasionally in GD specimens (Fig. 4a). No clear reactivity within the thyrocytes could be observed in any of the cryostat sections. The IgG2a isotype control MoAb did not detect any specific staining.

Fig. 4.

Immunocytochemical analysis of immune parameters on Hashimoto's gland (HT16). Cryostat sections (4 μm) obtained from HT16 were stained with: (a) MoAb to IL-10; (b) MoAb to T lymphocytes; (c) MoAb to B lymphocytes, as described in Materials and Methods; (d) MoAb to HLA-DR molecules. (a) Lymphomononuclear cells within dense infiltrates were positive whereas the thyrocytes were negative. Infiltrates with abundant T and B cell subpopulations were observed in (b) and in (c), respectively. (d) Positive thyrocytes were found in most fields.

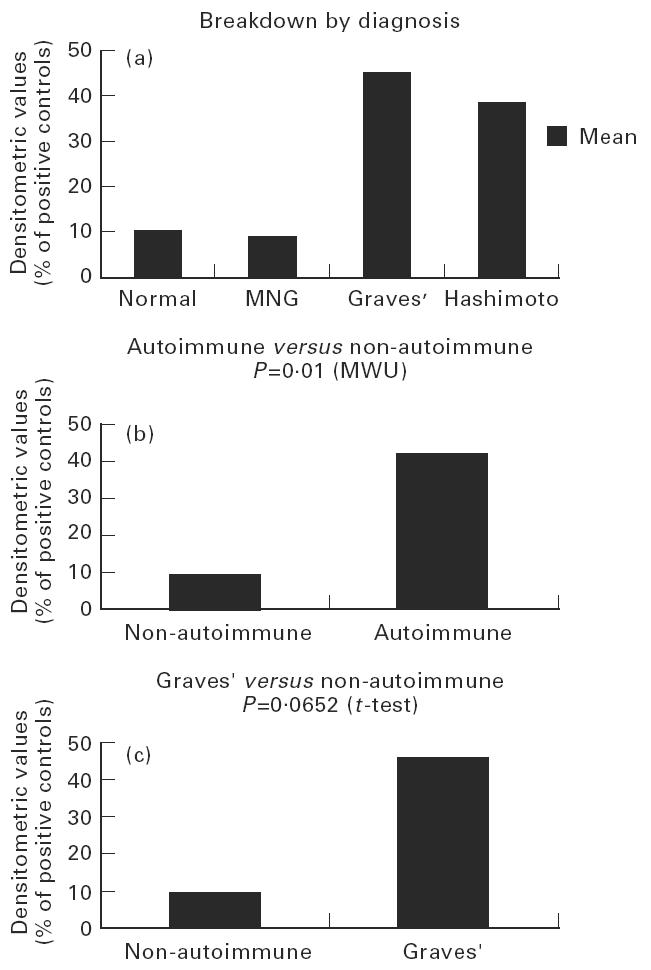

HLA class II and other immune parameter expression on thyrocytes

The overall results of the immunohistochemical analysis in the autoimmune thyroids nos 13–18 are summarized in Table 2. UCHT1 staining showed a high level of T lymphocytic infiltration in thyroids 16 and 17 (Fig. 4b) and to a lesser extent in thyroids 14 and 18. Thyroids 13 and 15 presented little T inflammatory component. Staining with CD20/CD37 revealed an important degree of B lymphocytic infiltration again in thyroids nos 16 and 17 (Fig. 4c) and to a lesser degree in thyroids nos 14 and 18. Membrane-bound IL-2 receptor staining with CD25 was positive only on lymphocytes in thyroid no. 17. A clear statistical correlation was found between HLA class II expression on thyrocytes and IL-10 mRNA levels, with Spearman's ρ = 0.8286 (P = 0.0416).

Table 2.

Immunohistochemical analysis and densitometric values of six autoimmune glands

After 48 h in culture all ‘normal’ control glands (nos 1–5), glands from patients with multinodular goitre (nos 6–10) and one GD thyroid (no. 11) expressed < 2% spontaneous HLA class II expression on thyrocytes. Graves thyroids nos 12 and 15 showed 8%, no. 13 11%, whereas thyroid no. 14 exhibited 40% and gland no. 16 70%. Out of the two Hashimoto's thyroids no. 17 expressed 95% and no. 18 showed 10% HLA-DR expression on thyrocytes, respectively. The in vivo HLA class II expression (Fig. 4d) paralleled that seen in vitro.

In vitro expression of HLA molecules in basal conditions and after treatment

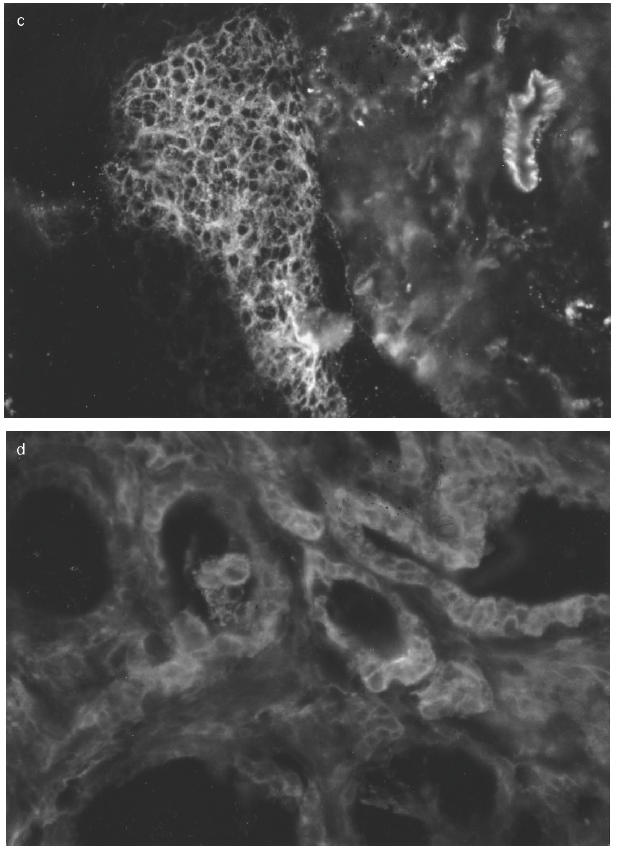

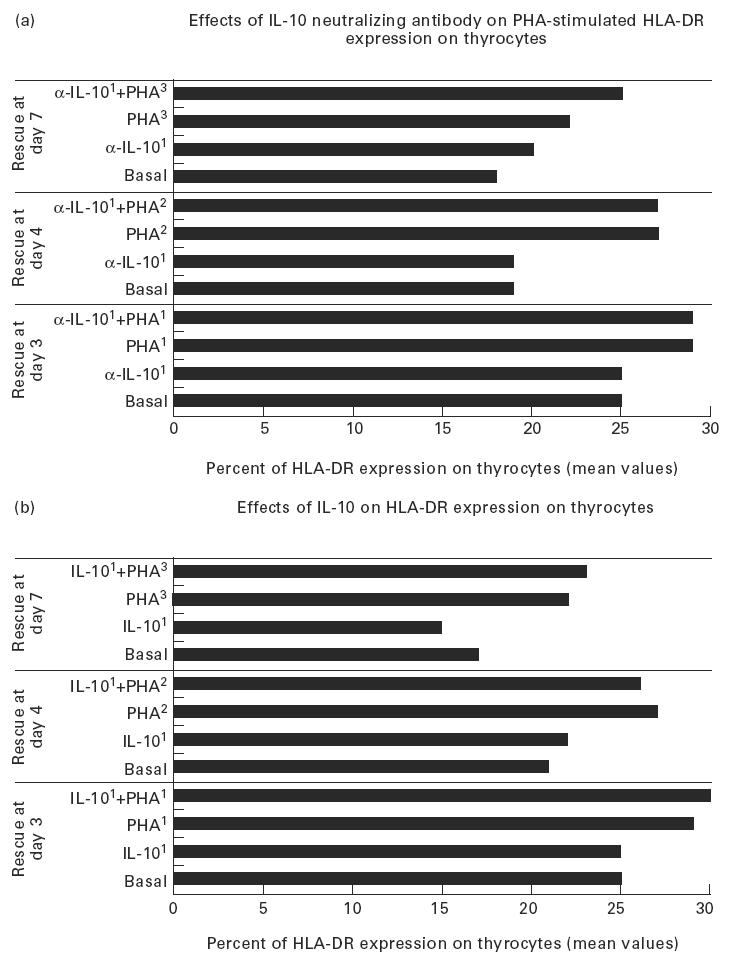

rhIL-10 did not substantially alter either spontaneous, IFN-γ- or PHA-induced HLA class II expression on cultured thyrocytes as assessed by FACS analysis. The intra-assay variation between the duplicates was always < 3%. The results of one set of experiments related to HLA-DR expression following IL-10 and PHA treatment are shown in Fig. 5a.

Fig. 5.

HLA class II expression on thyrocytes (mean values expressed in percentage) in basal conditions and after treatment with: (a) IL-10 and phytohaemagglutinin (PHA) added at day 1 (IL-101, PHA1), PHA added at day 2 (PHA2) or 3 (PHA3), IL-10 and PHA added at day 1 (IL-101 + PHA1), PHA added at day 2 or 3 (PHA2, PHA3) to cultures treated with IL-10 (IL-101 + PHA2 and IL-101 + PHA3, respectively). The cells were rescued at days 3, 4, 7; (b) neutralizing anti-IL-10 antibodies following the same protocol used for IL-10 treatment. No significant variation of the percentage expression of HLA class II molecules on thyrocytes was obtained. Experiments were performed in duplicate.

Neutralizing anti-IL-10 antibodies were not able to clearly affect spontaneous, IFN-γ- and PHA-induced HLA expression on thyrocytes. The results of one set of experiments are shown in Fig. 5b.

DISCUSSION

A significant enhancement of IL-10 mRNA expression was found in thyroids from patients with autoimmune thyroiditis in comparison with ‘non-autoimmune’ and other ‘control’ thyroids. IL-10 mRNA levels were particularly high in three of the autoimmune thyroids: two derived from patients with GD (nos 14 and 16) and one from a patient with Hashimoto's thyroiditis with a very large goitre (no. 17). Clinically, patient no. 14 suffered from a severe ophthalmopathy which required surgical decompression, and patient no. 17 had a particularly resistant form of thyroiditis which, despite subtotal thyroidectomy, eventually required radioactive treatment. All three patients had circulating thyroid antibodies at high titres (TPO antibodies ranging from 1602 to 3202) (Table 2). The histological findings of these three glands revealed an aggressive B and T lymphomononuclear cell infiltration and a high percentage of expression of HLA products on thyroid follicular cells (40–95%). The presence of IL-10 message and of its protein was restricted to lymphomononuclear cells within intensely infiltrated areas, thus supporting the hypothesis that IL-10 could be involved in leucocyte recruitment in vivo [24]. However, in the Hashimoto's thyroid showing the end-stage destruction of thyrocytes (no. 18), little IL-10 expression was found, even in the presence of still intense B and T lymphomononuclear infiltration. This would suggest that, if IL-10 played a role in human thyroid autoimmune disease, its involvement would be particularly relevant in the earlier stages of the disease process. IL-10 did not appear to regulate either the constitutive or the IFN-γ- or PHA-induced expression of HLA class II products on thyrocytes.

Human destructive thyroid autoimmune disease is known to be mainly a Th1-dependent autoimmune condition where an increased production of proinflammatory cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) has been demonstrated by thyroid epithelial cells and/or by infiltrating lymphomononuclear cells [28–31]. However, in GD this Th1-dependent polarization does not appear to be as definite [32,33]. In Hashimoto's thyroiditis this strongly Th1-polarized immune profile might be critical for the disease activity [34] and for the expression of immune activation molecules such as HLA class I and II on thyrocytes [35]. In clinically established autoimmunity, there is evidence from these and other studies [25,36,37] that Th1-dependent activity coexists with the Th2-related cytokine production within the same affected gland, but that in Hashimoto's Th1 response overrides the effects of anti-inflammatory Th2-dependent mediators such as IL-10.

Thus, the statistical correlation observed between the increased expression of IL-10 in the infiltrates and HLA class II expression on thyrocytes would indicate that the two parameters are expressed simultaneously in chronically infiltrated areas of autoimmune thyroids, rather than represent a direct influence of IL-10 on HLA expression on thyrocytes. Whether IL-10 plays a functional role against Th1 cytokine secretion in earlier stages of the thyroid autoimmune process, or whether this cytokine is involved in stimulating immunoglobulin production by B cells [15,38], still remains to be demonstrated experimentally. The present findings point towards the latter direction, as the patients with the highest levels of TPO also showed the highest levels of IL-10 (Table 2). This is in agreement with previous suggestions [39].

We conclude that IL-10 mRNA expression can be increased in thyroid autoimmune disease, both in GD and in Hashimoto's disease, but only in the presence of severe lymphomononuclear cell infiltration and in the less advanced stages of disease. When the autoimmune process has subsided, IL-10 expression progressively decreases, even in the presence of lymphomononuclear infiltration. It still remains to be fully explained why such a powerful Th1-inhibiting cytokine fails to prevent autoimmunity.

In animal models of thyroid and other autoimmune diseases, and in RA in humans, a ‘window’ of IL-10 treatment has been proposed among future novel strategies for immunointervention [19–26]. For human thyroid autoimmune disease, this possibility might be premature.

Acknowledgments

We are in debt to Professor A. W. Goode for supplying us with surgical specimens, to Dr C. Brown for offering his pathological expertise, to Dr M. W. Lowdell for helping us with the FACS analysis, and to Dr Sun Ying for his helpful advice on ISH technique. We are particularly grateful to Dr K. W. Moore and Dr M. G. Roncarolo for a gift of rhIL-10 and of the mouse cell line transfected with hIL-10 DNA, respectively. We thank Professor P. Lydyard and Professor P. Beverley for supplying us with MoAb reagents. Miss R. Groves and Mr A. Panagiotis (BSc students) have technically contributed with the work on ISH and flow cytometry. L.H. and J.C.V. were supported by the Autoimmune Diseases Charitable Trust, which has also financed this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.De Waal Malefyt R, Yssel H, Roncarolo MG, Spits H, De Vries JE. Interleukin 10. Clin Opin Immunol. 1992;4:314–20. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(92)90082-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mossmann TR. Proprieties and function of IL-10. Adv Immunol. 1994;56:1–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yssel H, De Waal-Malefyt R, Roncarolo MG, Abrams JS, Lahesmaa R, Spitz H, De Vries JE. IL-10 is produced by subsets of human CD4+ T cell clones and peripheral blood T cells. J Immunol. 1992;149:2378–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Del Prete G, De Carli M, Almerigogna F, Giudizi MG, Biagiotti R, Romagnani S. Human IL-10 is produced by both type I helper (Th1) and type 2 helper (Th2) T cell clones and inhibits their antigen-specific proliferation and cytokine production. J Immunol. 1993;150:353–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Waal Malefyt R, Abrams J, Bennett B, Figdor CG, De Vries JE. Interleukin 10 (IL-10) inhibits cytokine synthesis by human monocytes: an autoregulatory role of IL-10 produced by monocytes. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1209–20. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.5.1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burdin N, Peronne C, Bauchereau J, De Rousset F. Epstein Barr virus transformation induces B lymphocytes to produce human IL-10. J Exp Med. 1993;177:295–304. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.2.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benjamin D, Knobloch TJ, Dayton MA. Human B cell IL-10: B cell lines derived from patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and Burkitt's lymphoma constitutively secrete large quantities of IL-10. Blood. 1992;80:1289–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sad S, Marcotte R, Mosmann TR. Cytokine-induced differentiation of precursor mouse CD8+ T cells into cytotoxic CD8+ T cells secreting TH1 on the cytokines. Immunity. 1995;2:271–9. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Powrie F, Menon S, Coffman RL. IL-4 and IL-10 synergize to inhibit cell mediated immunity in vivo. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:3043–9. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830231147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brennan FM, Feldmann M. Cytokines in autoimmunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 1996;8:872–7. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fiorentino DF, Zlotnik A, Mosmann TR, Howard M, O'Garra AO. IL-10 inhibits cytokine production by activated macrophages. J Immunol. 1991;147:3815–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bogdan C, Paik J, Vodovotz Y, Nathan C. Contrasting mechanisms for suppression of macrophage cytokine release by TGFβ and IL-10. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:301–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aebisher I, Stadler BM. Th1-Th2 cells in allergic responses: at the limits of a concept. Adv Immunol. 1996;61:341–80. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60871-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Waal-Malefyt R, Haanen J, Spits H, et al. IL-10 and viral IL-10 strongly reduce antigen-specific human T cell proliferation by diminishing the antigen-presenting capacity of monocytes via down-regulation of class II MHC expression. J Exp Med. 1992;174:915–24. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.4.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Go N, Castle B, Barret R, et al. Interleukin 10 a novel B cell stimulatory factor: unresponsiveness of X chromosome-linked immunodeficiency B cells. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1625–31. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.6.1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rousset F, Garcia E, Defrance T, et al. IL-10 is a potent growth and differentiation factor for activated human B lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1890–3. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamura M, Uyemura K, Deans R, et al. Defining protective responses to pathogens: cytokine profiles in leprosy lesions. Science. 1991;254:277–9. doi: 10.1126/science.254.5029.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clerici M, Shearer GM. A Th1–Th2 switch is a critical step in the etiology of HIV infection. Immunol Today. 1993;14:107–11. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90208-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kennedy M, Torrance D, Picha K, Mohler K. Analysis of cytokine mRNA expression I in the central nervous system of mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis reveals that IL-10 mRNA expression correlates with recovery. J Immunol. 1992;149:2496–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rott O, Fleischer B, Cash E. Interleukin-10 prevents experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in rats. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:1434–40. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mignon-Godefroy K, Rott O, Brazillet MP, Charrière J. Curative and protective effects of IL-10 in experimental autoimmune thyroiditis (EAT) J Immunol. 1995;154:6634–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pennline KJ, Roque-Gaffney E, Monahan M. Recombinant human IL-10 (r-IL-10) prevents the onset of diabetes in the non-obese diabetic mouse. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1994;71:169–75. doi: 10.1006/clin.1994.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tisch R, McDevitt H. Insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. Cell. 1996;85:291–7. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81106-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wogensen L, Huang X, Sarvetnick N. Leukocyte extravasation into the pancreatic tissue in transgenic mice expressing interleukin 10 in the islets of Langerhans. J Exp Med. 1993;178:175–85. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.1.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katsikis PD, Cong-Qiv C, Brennan FM, Maini RN, Feldman M. Immuno-regulatory role of interleukin 10 in rheumatoid arthritis. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1517–27. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.5.1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen SBA, Katsikis PD, Chu C-Q, Thomssen H, Webb LMC, Maini RN, Londei M, Feldmann M. High level of IL-10 production by the activated T cell population within the rheumatoid synovial membrane. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;7:946–52. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyasaki A, Mirakian R, Bottazzo GF. Upregulation of adhesive molecules in the endothelium of thyroid glands affected by Graves' disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 1992;89:52–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb06876.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Prete GF, Tiri A, Mariotti S, Pinchera M, Rici M, Romagnani S. Enhanced production of IFNγ by thyroid-derived T cell clones from patients with Hashimoto's thyroiditis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1987;69:323–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Prete GF, Tiri A, De Carli M, Mariotti S, Pinchera I, Chretien S, Romagnani S, Rici M. High potential to TNFα production of thyroid infiltrating T lymphocytes in Hashimoto's thyroiditis: a peculiar feature of destructive thyroid autoimmunity. Autoimmunity. 1989;4:267–72. doi: 10.3109/08916938909014703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kennedy RL, Jones TH, Davies R, Justice SK, Leusine NR. Release of IL-6 by human thyroid epithelial cells immortalised by Simian virus 40 DNA transfection. J Endocrinol. 1992;133:4771–6. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1330477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diamant M, Kayser L, Rasmussen AK, Bech K, Feldt-Rasmussen U. IL-6 production by thyroid epithelial cells: enhanced by IL-1. Autoimmunity. 1991;11:21–26. doi: 10.3109/08916939108994704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watson PF, Pickerill AP, Davies R, Weetman AP. Analysis of cytokine gene expression in Graves disease and multinodular goitre. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79:355–60. doi: 10.1210/jcem.79.2.8045947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heuer M, Aust G, Ode-Hakin S, Scherbaum WA. Different cytokine mRNA profile in Graves disease, Hashimoto's thyroiditis, and non autoimmune disorders determined by quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) Thyroid. 1996;6:97–105. doi: 10.1089/thy.1996.6.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Charlton B, Lafferty K. The Th1/Th2 balance in autoimmunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;7:793–8. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bottazzo GF, Todd I, Mirakian R, Belfiore A, Pujol-Borrell R. Organ specific autoimmunity: a 1986 overview. Immunol Rev. 1986;94:137–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.1986.tb01168.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.André I, Gonzalez A, Wang B, Katz J, Benoist C, Mathis D. Checkpoints in the progression of autoimmune disease: lessons from diabetic models. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2260–3. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roura-Mir C, Catalfamo M, Sospedra M, Alcalde L, Pujol-Borrell R, Jaraquemada D. Single-cell analysis of intrathyroidal lymphocytes shows differential cytokine expression in Hashimoto's and Graves disease. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:3290–302. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ishida H, Muchamuel T, Sakagouchi S, Andrade S, Menon S, Howard M. Continuous administration of anti-interleukin 10 delays onset of autoimmunity in NZB/WF1 mice. J Exp Med. 1994;179:305–10. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ajjan RA, Watson PF, McIntosh RS, Weetman AP. Intrathyroidal cytokine gene expression in Hashimoto's thyroiditis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;105:523–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-784.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]