Abstract

Mannan-binding lectin (MBL) is an acute-phase protein which activates complement at the level of C4 and C2. We recently reported that the alternative pathway also is required for haemolysis via this ‘lectin pathway’ in human serum. CRP is another acute-phase reactant which activates the classical pathway, but CRP also inhibits the alternative pathway on surfaces to which it binds. Since serum levels of both proteins generally increase with inflammation and tissue necrosis, it was of interest to determine the effect of CRP on cytolysis via the lectin pathway. We report here that although CRP increases binding of C4 to MBL-sensitized erythrocytes, which in turn enhances lectin pathway haemolysis, it inhibits MBL-initiated cytolysis by its ability to inhibit the alternative pathway. This inhibition is characterized by increased binding of complement control protein H and decreased binding of C3 and C5 to the indicator cells, which in turn is attributable to the presence of CRP. Immunodepletion of H leads to greatly enhanced cytolysis via the lectin pathway, and this cytolysis is no longer inhibited by CRP. These results indicate that CRP regulates MBL-initiated cytolysis on surfaces to which both proteins bind by modulating alternative pathway recruitment through H, pointing to CRP as a complement regulatory protein, and suggesting a co-ordinated role for these proteins in complement activation in innate immunity and the acute-phase response.

Keywords: acute phase, C-reactive protein, mannan-binding lectin, complement, lectin pathway

INTRODUCTION

During the acute phase of many diseases a group of proteins increases in concentration in the blood. Serum levels of these proteins can serve as indicators of the presence and extent of inflammation and tissue necrosis. Several of the acute-phase proteins also have been linked to natural immunity and host defence, including the mannan-binding lectin (MBL) and CRP. MBL is thought to play an important role in innate immunity by recognizing and opsonizing certain microorganisms [2–5]. As a C-type lectin, MBL can bind specifically to terminal non-reducing sugars, including N-acetylglucosamine, mannose, fucose and glucose [2–5]. MBL shares structural similarity with C1q [2–4], and likewise associates with two recently discovered serine proteases, MASP-1 [6,7] and MASP-2 [8]; this complex activates the complement system at the level of C4 and C2 [6,9–11] in a series of interactions that has been termed the ‘lectin pathway’ of complement activation. We recently reported that in contrast to antibody-initiated activation of the classical pathway, the alternative pathway as well as C4 and C2 is required for haemolysis via this MBL-initiated complement activation pathway [12].

CRP is another acute-phase reactant which binds to a limited group of widely distributed ligands including phosphocholine and certain polycations and polysaccharides found on the surface of bacteria, mammalian membranes and necrotic tissue, and has the ability to activate leucocytes and the complement system [13,14]. CRP activates complement via the classical pathway at the level of C1q [13,14], but also inhibits the activation of the alternative pathway on surfaces to which it binds, by increasing complement regulatory protein H binding to C3b [15,16]. Since both MBL and CRP have pronounced and distinctive interactions with the complement system, it was of interest to study complement activation in the presence of both these proteins. We report here that, despite its ability to enhance C4 binding, CRP inhibits complement-mediated cytolysis via the lectin pathway by blocking recruitment of the alternative pathway through its effect on factor H.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Buffers

Gelatin-veronal-buffered saline consisting of 5 mm veronal pH 7.4, 0.145 m NaCl and 0.1% gelatin (GVB); GVB containing 10 mm CaCl2 and 0.5 mm MgCl2 (GVB++); and GVB containing 10 mm EDTA (EDTA–GVB) were prepared as previously described [17]. The choice of buffers contrasts with our previous report on lectin pathway-mediated haemolysis [12] in which Mg–EGTA was the predominant buffer used; this is because, in contrast to MBL, CRP requires the presence of calcium for both binding and retention to its ligands on the E surface.

Reagents

Saccharomyces cerevisiae mannan (M) was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO). Monoclonal anti-MBL antibody was purchased from Statens Serum Institut (Copenhagen, Denmark). Human CRP, phosphocholine-conjugated bovine serum albumin (PC–BSA) and monoclonal mouse anti-human CRP were prepared as previously described [18]. Anti-human C4, C3, C5 and H were purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). Streptavidin conjugated with R-PE was purchased from Dako (Glostrup, Denmark), for use in flow cytometry.

Sera and complement components

C7-deficient serum [17], C3-depleted human serum purchased from Calbiochem and agammaglobulinaemic human serum (AHS) collected from patients with common variable immunodeficiency, respectively, were stored at −70°C. Every AHS used had < 2% normal haemolytic activity upon incubation with sheep erythrocytes (E), whereas normal levels were shown when antibody-sensitized E (EA) were used as the indicator cells. The C-deficient sera were shown to have < 2% normal haemolytic activity, with normal levels restored upon addition of small amounts of the purified missing human component, and were absorbed with M-sensitized E before use. Purified human C3 and C7 were purchased from Calbiochem. Purified H was prepared as previously described [16].

Preparation of H-depleted agammaglobulinaemic human serum

H-depleted agammaglobulinaemic human serum was prepared by immunoaffinity chromatography as previously described [19]. Briefly, 2 ml agammaglobulinaemic human serum was made 10 mm with EDTA and passed through an anti-H-Sepharose 4B immunoabsorbent column (10 ml) which had been equilibrated with EDTA–VBS. The effluent was concentrated to the original serum volume using a microconcentrator, and had an H level of ≈ 8 μg/ml (starting level 800 μg/ml).

MBL

Human MBL was prepared by sequential affinity column chromatography by minor modification of the method of Kawasaki et al. [20]. Briefly, human serum (1200 ml) obtained by recalcification of pooled human citrated plasma of known MBL concentration was brought to 20 mm CaCl2 and allowed to clot for 1 h at 37°C and overnight at 4°C. After removal of the clot, the serum was dialysed extensively against ‘starting buffer’ containing 50 mm Tris–HCl, 1 m NaCl, 20 mm CaCl2 and 0.05% (w/v) NaN3 (pH 7.8). After centrifugation at 10 000 g for 10 min, the supernatant was applied to a mannan-Sepharose 4B column (100 ml) which had been equilibrated with starting buffer. The column was washed with starting buffer and the bound proteins were eluted with a buffer containing 50 mm Tris–HCl, 1 m NaCl and 20 mm EDTA pH 7.8. The eluate was brought to 50 mm CaCl2 and reapplied to a second, smaller (25 ml) otherwise identical mannan-Sepharose 4B column, and the bound proteins were eluted in the same manner as the first column. The proteins eluted were pooled and passed through protein A-Sepharose (10 ml) and goat anti-human IgM-Sepharose (20 ml) columns, respectively, to remove anti-mannan antibodies. Effluents from these columns were pooled, dialysed against ‘starting buffer’, and stored in aliquots at −70°C.

Preparation of antibody-sensitized and mannan-coated erythrocytes

Antibody-sensitized sheep erythrocytes (EA) [21], and E coated with mannan (E-M) and sensitized with MBL (E-M-MBL) were prepared as previously described [9,11,22]. Briefly, 0.5 ml sheep E (1 × 109 cells/ml) were mixed 0.5 ml CrCl3 solution (0.5 mg/ml), 0.5 ml mannan solution (200 μg/ml) was added and the mixture was incubated with occasional shaking for 5 min at 25°C. The reaction was stopped by adding 1.5 ml ice-cold GVB++, and the E-M were washed three times and resuspended to a final concentration of 1 × 109 cells/ml in GVB++. An aliquot (0.1 ml) was added to 0.4 ml MBL (2000 ng) in GVB++, incubated with gentle shaking for 30 min at room temperature for 30 min at 0°C, washed and resuspended to 1 × 108 cells/ml in GVB++.

Preparation of PC-coated E

PC-coated E (E-PC) also were prepared by the chromic chloride method [22]. Briefly, 0.5 ml sheep E (1 × 109 cells/ml) were mixed with 0.5 ml CrCl3 solution (0.5 mg/ml), 0.5 ml PC–BSA solution (0.1–10 mg/ml) was added and the mixture was incubated with occasional shaking for 5 min at 25°C. The reaction was stopped by adding 1.5 ml ice-cold GVB++, and the E-PC were washed three times and resuspended to a final concentration of 1 × 109 cells/ml in GVB++. CRP-sensitized E-PC (E-PC-CRP) were prepared by mixing equal volumes of CRP solution (1–1000 μg/ml) and aliquots of the E-PC suspension in GVB++ (1 × 109 cells/ml) for 30 min at room temperature, 30 min at 0°C, washed and resuspended to 1 × 108 cells/ml in GVB++.

Preparation of indicator cells containing C4, C3 and C5

Indicator cells containing C4; C3 and C5 (EAC4,3,5; E-M-MBL-C4,3,5; E-PC-CRP-C4,3,5; and E-M-MBL-PC-CRP-C4,3,5) were prepared as previously described [21]. Indicator cells were washed three times and resuspended to 1 × 109 cells/ml in GVB++, prewarmed to 30°C. An equal volume of 1:10 dilution of C7-deficient human serum was added slowly with continuous shaking, and after 30 min incubation at 30°C the mixture was washed, resuspended to the original volume in GVB++, and incubated for another 1 h to decay off C2. The resulting indicator cells containing C4, C3 and C5 were washed and resuspended to the original volume in GVB++.

Haemolytic assays

Lectin pathway activity (‘LH50’) was assayed by lysis of E-M-MBL in Mg-EGTA as follows. E-M-MBL (100 μl containing 1 × 108 cells/ml in Mg-EGTA) were incubated with 100 μl/test human serum in Mg-EGTA at 37°C for 1 h, centrifuged, and the OD414 of the supernatant, percent lysis and amount of serum generating 50% lysis were determined in the usual way [12,17,21]; units are expressed as the dilution of serum added in 0.1 ml yielding 50% haemolysis. The CH50 and AH50 were determined as previously described [17,21].

ELISA for H

H concentrations were assayed by a sandwich ELISA methodology. Briefly, microtitre plates were coated with anti-H (5 μg/ml; 100 μl/well) in coating buffer (0.03 m Na2CO3, 0.02 m NaHCO3, pH 9.6) and incubated overnight at 4°C. The microtitre plates were washed three times with veronal (5 mm)-buffered saline pH 7.4 containing 0.05% Tween 20 (VBS–T), and blocked 2 h at room temperature by adding 200 μl VBS containing 1% BSA to each well. Samples and H standards were loaded into the wells in duplicate, incubated at room temperature for 1 h and washed as before. Biotinylated anti-H diluted in VBS (100 μl, 2 μg/ml) was added to each well, followed by incubation at room temperature for 1 h. The plates were washed, streptavidin–horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate (1:1000 in VBS, 100 μl/well) was added, incubation was continued at room temperature for 1 h, and after additional washes, 100 μl substrate were added. Incubation was continued for 30 min at room temperature, the reaction was stopped by addition of 2 n HCl (100 μl/well), and the absorbance at 450 nm was read on a microplate reader.

Flow cytometry assay of MBL, CRP, C4, C3, C5 and H on sheep E

The indicator cells (100 μl; 1 × 108 cells/ml) were mixed with 100 μl of 1:100 biotinylated antisera to human MBL, CRP, C4, C3, C5 or H and incubated at 4°C for 1 h. After washing three times, 100 μl 1:10 R-PE-conjugated streptavidin solution were added and incubated for 1 h at 4°C. The washed cells were resuspended to 1 ml and assayed for coated protein using an Ortho Cytoron flow cytometer (Ortho Diagnostic Systems, Raritan, NJ) to quantify orange fluorescence. The fluorescence of cells is presented as the mean channel intensity of fluorescence (MCF) of 1 × 104 cells as measured using logarithmic amplification, except as noted. In this configuration, a 22-channel increase represents an approximate doubling of fluorescence [23].

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed, in duplicate, a minimum of three times. Data from representative experiments are shown; the s.e.m. were < 10% in Figs 1,2 and 4 and < 15% in Fig. 3.

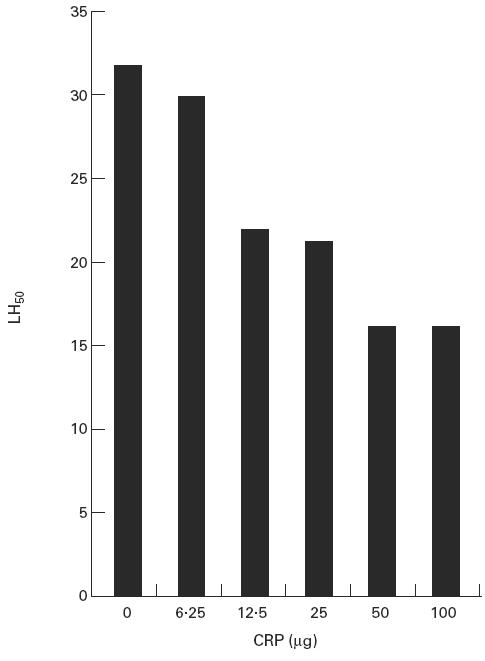

Fig. 1.

CRP inhibition of mannan-binding lectin (MBL)-initiated haemolysis. Indicator sheep erythrocytes optimally coated with phosphocholine-conjugated bovine serum albumin (PC–BSA) and mannan were reacted with MBL (1 μg) and increasing amounts of CRP prior to the addition of agammaglobulinaemic human sera; lysis was determined as described. No lysis was observed with E-PC sensitized with CRP alone.

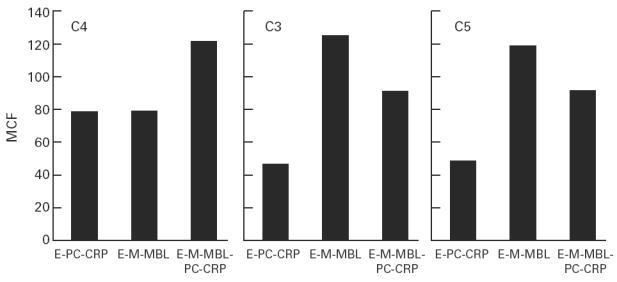

Fig. 2.

Binding of C4, C3 and C5 to CRP- and mannan-binding lectin (MBL)-sensitized indicator cells. Sheep erythrocytes (E) were coated with phosphocholine-conjugated bovine serum albumin (PC–BSA), mannan or both ligands, sensitized with CRP (50 μg), MBL (1 μg) or both molecules, and reacted with C7-deficient human serum as described; after appropriate washes, the cells were reacted with biotinylated antisera to C4, C3 and C5, respectively, and the mean channel fluorescence (MCF) was calculated in the usual way.

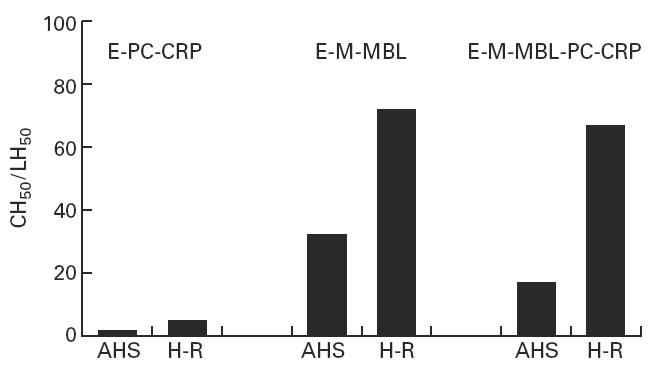

Fig. 4.

Effect of CRP on mannan-binding lectin (MBL)-initiated haemolysis in H-depleted serum. Lysis of E-M-MBL was greatly increased in agammaglobulinaemic human sera (AHS) that was depleted of H (H-R) (centre panel), and addition of CRP did not inhibit haemolysis in H-depleted serum (right panel). H depletion also led to a small, but significant, degree of haemolysis of CRP-sensitized E-PC.

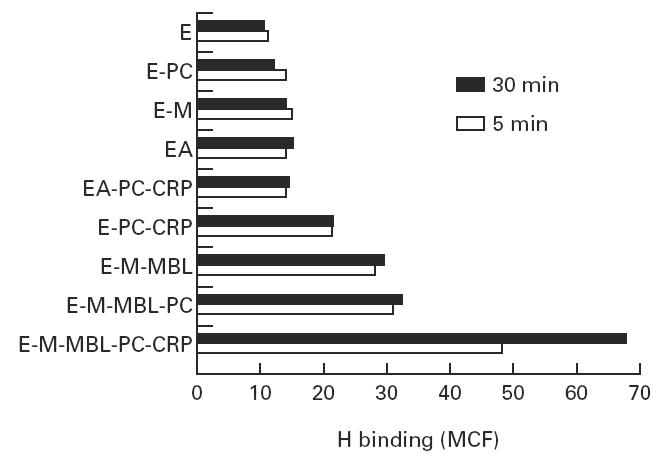

Fig. 3.

H binding to CRP- and mannan-binding lectin (MBL)-sensitized indicator cells. Indicator cells were prepared as described, and reacted with C7-deficient human serum; H binding was determined as mean channel fluorescence (MCF) after 5 and 30 min incubation, respectively.

RESULTS

CRP inhibition of lectin pathway-mediated haemolysis

We first tested the lysis of ligand-coated E using agammaglobulinaemic sera to avoid the effects of natural antibodies in GVB++ in the presence of MBL and CRP, respectively. While E-M were readily lysed (32 haemolytic units or LH50/ml) upon the addition of MBL (2 μg/108 cells), no significant lysis (< 2 LH50/ml) was observed upon addition of CRP to E coated with PC–BSA (E-PC) under identical conditions; similar results were obtained with E coated with both M and PC–BSA (data not shown). The addition of CRP to E-M-PC sensitized with MBL resulted in significant inhibition of MBL-initiated haemolysis, and inhibition increased as increasing amounts of CRP were used; a maximum two-fold inhibition (to 16 LH50/units) was observed with optimal CRP (50 μg CRP/109 cells) sensitization (Fig. 1). Binding of CRP to E-M-PC did not reduce the amount of MBL bound to these cells, showing that the inhibition did not involve competition between the acute-phase proteins for binding sites on the indicator cells. No inhibition was noted upon addition of CRP to E-M-MBL which had not been coated with PC, indicating that CRP inhibits lectin pathway activity only on surfaces to which it is bound. The concentrations of acute-phase proteins used, as well as the 2.5:1 ratio of CRP (5 μg/108 cells) to MBL (2 μg/108 cells) used in sensitization of the E, are well within upper levels reported in the acute-phase response (250 μg CRP/ml and ≈ 10–20 μg MBL/ml) [24–26].

Binding of C components to mannan- and PC-coated indicator cells

To characterize further C activation in this system, the indicator cells were tested for C4, C3 and C5 binding. Absorbed C7-deficient serum rather than AHS was used to prevent lysis of the C-coated cells, and E-M and E-PC were prepared to yield equivalent levels of C4 binding. As shown in Fig. 2, under conditions of normalized C4 binding, CRP-sensitized cells bound less C3 and C5 than did cells sensitized with MBL. The addition of CRP to E-M-PC sensitized with MBL led to increased binding of C4, but decreased binding of C3 and C5, compared with that observed with MBL sensitization alone.

MBL and CRP enhancement of H binding to cell-bound C3b

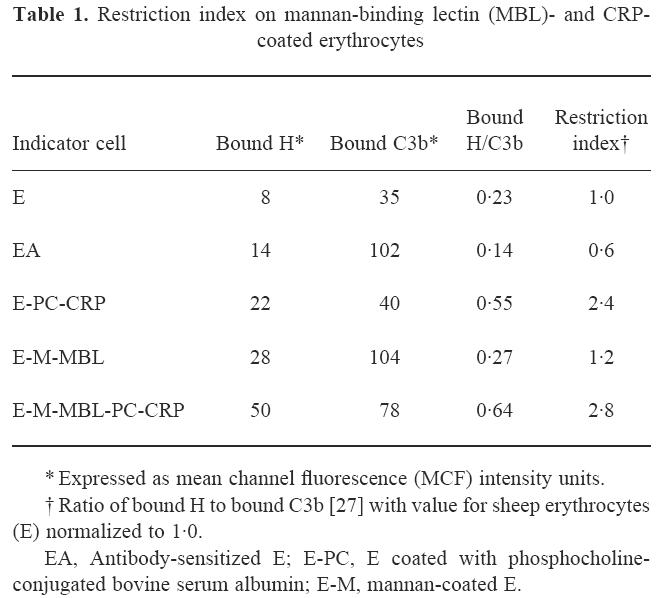

Since previous studies had demonstrated that H binding to C3b is increased on CRP-sensitized Streptococcus pneumoniae and PC-coated E [15,16], we next investigated the binding of H to the E-M-MBL used to quantify cytolysis via the lectin pathway. As shown in Fig. 3, relatively high binding of H was observed upon incubation of E-PC-CRP and E-M-MBL with C7-deficient serum, and interestingly, much higher levels were seen when cells sensitized with both MBL and CRP (E-M-MBL-PC-CRP) were used. H binding to EA was comparable to negative control indicator cells, and there was no H binding to control chromic chloride-treated E, either in C3-deficient serum or when purified H was added to E-M-MBL, demonstrating the specificity of the reaction. Similarly, no significant H binding was observed in the absence of C3b, indicating that H indeed was binding to C3b on the cell surface. The increased H binding required the presence of CRP, since removal of CRP by washing with EDTA-GVB after the C3- and C5-bearing cells were produced restored H binding to a level comparable to that observed with either E-M-MBL or E-PC in absence of CRP (data not shown). The decreased alternative pathway activity in the presence of CRP was reflected in the restriction index (Table 1), the ratio of bound H to bound C3b [27], which is < 1.0 for alternative pathway activators. The restriction index of E-M-MBL (1.2) increased more than two-fold (to 2.8) upon the addition of CRP.

Table 1.

Restriction index on mannan-binding lectin (MBL)- and CRP-coated erythrocytes

Absence of CRP inhibition of lectin pathway-mediated haemolysis in H-depleted serum

The correlation of CRP inhibition with H binding raised the question of whether H was required for the inhibition to occur. To test this possibility, E-M-MBL were reacted in AHS depleted of H by immunoabsorbtion (Fig. 4). The cells showed markedly increased lysis in H-depleted serum (78 compared with 32 LH50 U/ml), and in contrast to the inhibition of lysis in untreated AHS (to 16 LH50 U/ml), lysis was not reduced at all in the presence of CRP in serum depleted of H, remaining at 78 LH50 U/ml. Re-addition of H to the depleted serum resulted in decreased haemolysis of E-M-MBL to the levels seen in unmodified AHS, and restored the inhibitory effect of CRP (data not shown). These results indicate that H is a significant regulator of the lectin pathway, and that this regulation is modulated by CRP. Further, whereas CRP-sensitized E-PC were not lysed (< 2 CH50 U/ml) in unmodified AHS, a small but distinct degree of lysis (4.3 ± 1.5 CH50 U/ml) regularly was observed in AHS depleted of H, indicating that H is a significant modulator of haemolytic complement activity initiated by CRP.

DISCUSSION

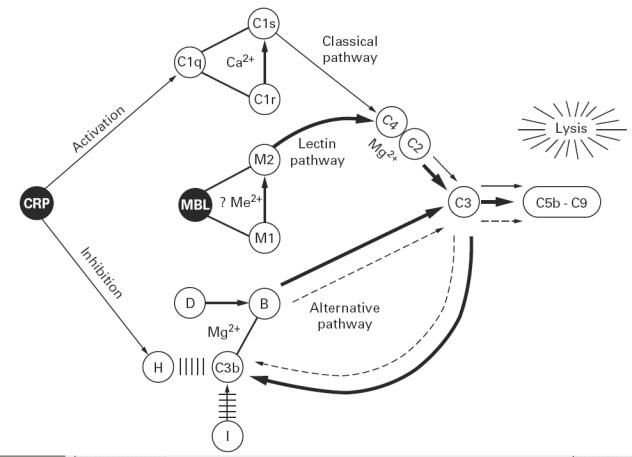

The acute-phase reactants MBL and CRP have been linked to natural immunity and host defence [2–5,13,14], in large part because of their ability to activate the complement system. Even though both proteins are commonly elevated during acute inflammatory reactions, the combined effects of MBL and CRP on complement activation have not previously been reported. We therefore investigated the effects of CRP on complement activation by MBL when ligands for both acute-phase proteins were present on the same cell. It seemed plausible that co-sensitization with CRP would increase haemolysis by MBL via the lectin pathway, since C activation by CRP leads to substantial consumption and binding of C4 by its ability to activate the classical pathway [13], and presensitization with C4 significantly increases lysis of E sensitized with M and MBL [12]. However, it seemed equally possible that CRP would inhibit MBL-initiated haemolysis by its propensity to inhibit alternative pathway activation on surfaces to which it is bound [15,16]. The present experiments clearly show that the latter effect predominates when ligand-coated E are used as the indicator cells, pointing to the strength of the alternative pathway inhibitory activity of CRP. Although MBL is known to activate the classical complement pathway, these experiments also emphasize the obligatory role of the alternative pathway in cytolysis initiated through the lectin pathway (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Diagrammatic sketch of the effects of CRP and mannan-binding lectin (MBL) on complement activation, indicating the classical pathway (thin solid line), alternative pathway (dotted line) and lectin pathway (heavy solid line); arrows other than the directional indicators from CRP indicate enzymatic cleavages. CRP activates the classical pathway via C1q, but inhibits the alternative pathway by enhancing the interaction between H and C3b, displacing B from C3b and increasing inactivation of C3b by I. This latter effect predominates during complement activation by both MBL and CRP, and hence CRP inhibits C-dependent lysis initiated by MBL via the lectin pathway. It is not yet clear whether a divalent cation (e.g. Mg2+) is required for interactions of MBL with the MASP-1 and MASP-2 (M1 and M2).

The inhibitory activity of CRP could be attributed to its ability to enhance the reaction between H and C3b. The presence of CRP greatly enhanced the binding of H to MBL-sensitized indicator cells, and when H was immunodepleted from serum, inhibition was no longer observed, while inhibition was restored upon re-addition of H. It is not yet clear how CRP enhances the binding of H to C3b. We have observed H binding to CRP on microtitre plates (C.M., unpublished observations). However, on the sensitized E studied here as well as on S. pneumoniae in previous studies [16], H binding required cell-bound C3b. It is possible that CRP provides secondary sites which increase the binding of H to C3b on the target. Thus, no significant binding of H was observed when MBL-sensitized E were reacted in C3-deficient human serum or when purified H was added to MBL-sensitized E in the absence of C3. The CRP-enhanced binding of H probably inhibits C5 convertase formation and activity as well as feedback amplification of C3 deposition by displacing B from C3b and favouring the cleavage of C3b to haemolytically inactive iC3b by I as previously described [28–30]. However, it is not yet clear how CRP enhances the binding of H to C3. The binding of H to E-M-MBL was significantly greater than to CRP-sensitized E-PC, which in turn was greater than to EA, when these each were reacted with comparable amounts of NHS. The relatively poor H binding to EA may reflect the ability of immunoglobulin to protect nascent C3b from breakdown by H and I [31,32]. These experiments also indicate that H is a regulator of CRP-initiated classical pathway activation, since lysis of CRP-sensitized cells, which is minimal at best in most experimental systems [33,34], was increased when H was depleted.

The serum levels of MBL and CRP increase during inflammatory reactions, and binding sites for both reactants may become available at sites of inflammation and tissue necrosis, permitting concomitant deposition and complement activation by both acute-phase proteins. Perhaps there is biological advantage to the enhanced activation of early acting C components when both acute-phase proteins react with ligands on the same cells, with its potential for promoting phagocytosis, along with pre-emptive inhibition of the membrane-damaging effects of the later acting C macromolecular attack complex by the inhibitory effect of CRP as described here. The present experiments indicate that H is a significant regulator of MBL-initiated cytolysis, that this regulation is modulated by CRP, and that the complement-activating functions of CRP and MBL are co-ordinated in the acute-phase response. They also support the concept that regulation of complement activation via the alternative pathway represents a major function of CRP.

Acknowledgments

This study was presented in part to the annual meeting of the Association of American Physicians in Washington DC, May 1, 1998 [1]. These investigations were supported in part by a Thai Royal Government Scholarship to C.S. and a National Institutes of Health grant to C.M., and are presented by C.S. and Y.Z. in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the PhD from Rush University. H.G. holds the Thomas J. Coogan Chair in Immunology/Microbiology established by Marjorie Lindheimer Everett.

References

- 1.Suankratay C, Mold C, Zhang Y, et al. Complement activation in the acute phase response: inhibition of mannan-binding lectin-initiated complement cytolysis by C-reactive protein. J Invest Med. 1998;46:219A. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00663.x. (Abstr.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holmskov U, Malhotra R, Sim RB, et al. Collectins: collagenous C-type lectins of the innate immune system defense system. Immunol Today. 1994;15:67–74. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoppe H, Reid KBM. Collectins: soluble proteins containing collagenous regions and lectin domains and their role in innate immunity. Protein Sci. 1994;3:1143–58. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Epstein J, Eichbaum Q, Sheriff S, et al. The collectins in innate immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 1996;8:29–35. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drickamer K, Taylor ME. Biology of animal lectins. Ann Rev Cell Biol. 1993;9:237–64. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.001321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsushita M, Fujita T. Activation of the classical complement pathway by mannose-binding protein in association with a novel C1s-like serine protease. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1497–502. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.6.1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sato T, Endo Y, Matsushita M, et al. Molecular characterization of a novel serine protease involved in activation of the complement system by mannose-binding protein. Int Immunol. 1994;6:665–9. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.4.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thiel S, Vorup-Jensen T, Stover CM, et al. A second serine protease associated with mannan-binding lectin that activates complement. Nature. 1997;386:506–10. doi: 10.1038/386506a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ikeda K, Sannoh T, Kawasaki N, et al. Serum lectin with known structure activates complement through the classical pathway. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:7451–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ji Y-H, Matsushita M, Okada H, et al. The C4 and C2 but not C1 components of complement are responsible for the complement activation triggered by the Ra-reactive factor. J Immunol. 1988;141:4271–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ji Y-H, Fujita T, Hatsuse H, et al. Activation of the C4 and C2 components of complement by a proteinase in serum bactericidal factor, Ra reactive factor. J Immunol. 1993;150:571–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suankratay C, Zhang X-H, Zhang Y, et al. Requirement for the alternative pathway as well as C4 and C2 for complement-dependent hemolysis via the lectin pathway. J Immunol. 1998;160:3006–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gewurz H, Zhang X-H, Lint TF. Structure and function of the pentraxins. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;7:54–64. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szalai AJ, Agrawal A, Greenhough TJ, et al. C-reactive protein: structural biology, gene expression, and host defense function. Immunol Res. 1997;16:127–36. doi: 10.1007/BF02786357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mold C, Gewurz H. Inhibitory effect of C-reactive protein on alternative C pathway activation by liposomes and Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Immunol. 1981;127:2089–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mold C, Kingzette M, Gewurz H. C-reactive protein inhibits pneumococcal activation of the alternative pathway by increasing the interaction between factor H and C3b. J Immunol. 1984;133:882–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeitz HJ, Miller GW, Lint TF, et al. Deficiency of C7 with systemic lupus erythematosus: solubilization of immune complexes in complement-deficient sera. Arthritis Rheum. 1981;24:87–93. doi: 10.1002/art.1780240114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ying SC, Shephard E, de Beer FC, et al. Localization of sequence-determined neoepitopes and neutrophil digestion fragments of C-reactive protein utilizing monoclonal antibodies and synthetic peptides. Molec Immunol. 1992;74:677–87. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(92)90205-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sim RB, Day AJ, Moffatt BE, et al. Complement factor I and cofactors in control of complement system convertase enzymes. Methods Enzymol. 1993;223:13–35. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)23035-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawasaki N, Kawasaki T, Yamashina I. Isolation and characterization of a mannan-binding protein from human serum. J Biochem. 1983;94:937–47. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a134437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrison RA, Lachmann PJ. Complement technology. In: Weir DM, editor. Handbook of experimental immunology. Vol. 39. Palo Alto: Blackwell Scientific Publications, Inc.; 1986. pp. 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perruca PJ, Faulk WP, Fudenberg HH. Passive immune lysis with chromic chloride-treated erythrocytes. J Immunol. 1969;102:812–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spear GT, Takefman DM, Sullivan BL, et al. Anti-cellular antibodies in sera from vaccinated macaques can induce complement-mediated virolysis of human immunodeficiency virus and simian immunodeficiency virus. Virology. 1993;195:475–80. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Claus DR, Osmand AP, Gewurz H. Radioimmunoassay of human C-reactive protein and levels in normal sera. J Lab Clin Med. 1976;87:120–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thiel S, Holmskov U, Hviid L, et al. The concentration of the C-type lectin, mannan-binding protein, in human plasma increases during an acute phase response. Clin Exp Immunol. 1992;90:31–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb05827.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aittoniemi J, Rintala E, Miettinen A, et al. Serum mannan-binding lectin (MBL) in patients with infection: clinical and laboratory correlates. APMIS. 1997;105:617–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1997.tb05062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pangburn MK, Morrison DC, Schreiber RD, et al. Activation of the alternative complement pathway: recognition of surface structures on activators by bound C3b. J Immunol. 1980;124:977–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Isenman DE, Podack ER, Cooper NR. The interaction of C5 with C3b in free solution: a sufficient condition for cleavage by a fluid C3/C5 convertase. J Immunol. 1980;124:326–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DiScipio RG. The binding of human complement proteins C5, factor B, β1H, and properdin to complement fragment C3b on zymosan. Biochem J. 1981;199:485–6. doi: 10.1042/bj1990485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ito S, Tamura N. Inhibition of classical C5 convertase in the complement system by factor H. Immunology. 1983;50:631–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Medof ME, Lam T, Prince G, et al. Requirement for human red blood cells in inactivation of C3b in immune complexes and enhancement of binding to spleen cells. J Immunol. 1983;130:1336–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fries LF, Gaither TA, Hammer CH, et al. C3b covalently bound to IgG demonstrates a reduced rate of inactivation by factor H and I. J Exp Med. 1984;160:1640–55. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.6.1640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Osmand AP, Mortensen RF, Siegel J, et al. Interactions of C-reactive protein with the complement system. III. Complement-dependent passive hemolysis initiated by CRP. J Exp Med. 1975;142:1065–77. doi: 10.1084/jem.142.5.1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berman S, Gewurz H, Mold C. Binding of C-reactive protein to nucleated cells leads to complement activation without cytolysis. J Immunol. 1986;136:1354–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]