Abstract

Surgical interventions and cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) induce a systemic inflammatory response with cytokine release. Ageing is perceived as a process of impaired immune functions: IL-1β, IL-6 and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) secretion are increased while IL-2 release is reduced in advanced age. At present, little information is available about perioperative immune reactions at different stages of ageing. The aim of the present study was to compare IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-10 and soluble IL-2 receptor (sIL-2R) in younger and older patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Male patients (n = 14) undergoing elective coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery employing CPB with moderate hypothermia were divided into two groups according to their age: group 1 included seven patients < 50 years old, group 2 included seven patients > 65 years old. All patients received general anaesthesia using a balanced technique with sufentanil, isoflurane and midazolam. Blood samples were collected pre-operatively (T1); intra-operatively during CPB (T2); post-operatively on the day of surgery (T3); on the first post-operative day (T4). Blood concentrations of IL-6, IL-1β, IL-10, TNF-α and sIL-2R were measured using commercially available ELISA kits and corrected for plasma cell volume. Statistical analysis was performed by non-parametric analysis of variance and Mann–Whitney U-test. Significance level was set to P < 0.05. There were no statistically significant differences in the perioperative release of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-10 and sIL-2R among the two groups. We conclude that the perioperative course of cytokine release in patients undergoing CABG surgery with CPB and comparable perioperative management does not significantly differ in the two age groups.

Keywords: cytokine, age, cardiac surgery, perioperative, IL-10, IL-6, IL-1β, tumour necrosis factor, IL-2R

INTRODUCTION

Surgical interventions and cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) are medical conditions that induce a systemic inflammatory response, activating the complement system and triggering the release of cytokines [1–4]. IL-6, IL-1β and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) are main mediators of the acute-phase inflammatory responses [5,6].

Ageing is assumed to be accompanied by a process of impaired immune functions [7,8]. Several age-related changes of the immune system have been reported: humoral immunity shows a tendency to rise, while cellular immune responses generally decrease with age [7,9–11]. Lehtonen et al. [12] and Sansoni et al. [13] reported that the number of lymphocytes was decreased in healthy elderly subjects.

Other investigators found that in the elderly IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α levels were increased, while IL-2 release was reduced [14–17]. Sindermann et al. [18] reported decreased levels of soluble IL-2 receptor (sIL-2R) after phytohaemagglutinin (PHA) stimulation in elderly compared with younger persons.

Results of experimental studies suggest that increased cytokine production may have an adverse impact on the stability of several physiological systems [19,20]. In human cardiac tissue IL-6, IL-2 and TNF-α have a negative inotropic effect [21]. It has been shown that perioperative cytokine release is associated with cardiovascular instability in patients undergoing cardiac surgery [22].

At present, little information is available about the perioperative release of the pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines at different ages. To our knowledge, there have been no studies investigating the cytokine changes in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery according to their age.

The aim of the present study was to compare blood levels of IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-10 and sIL-2R in younger and older patients undergoing cardiac surgery.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

After approval by the institutional review board, written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Subjects

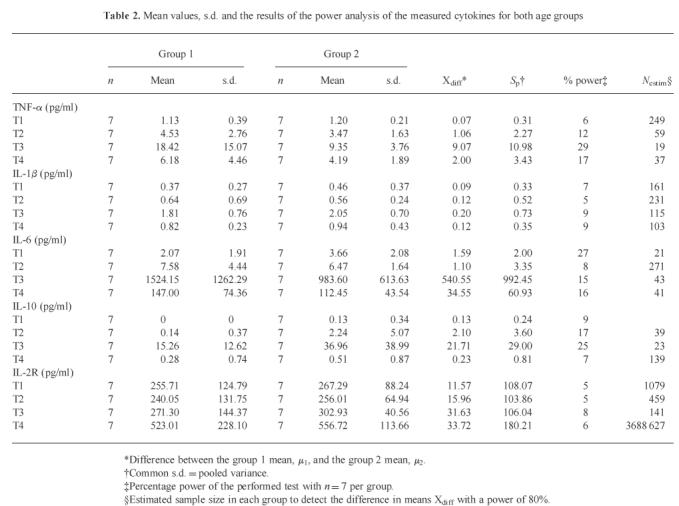

Fourteen male patients scheduled for elective CABG surgery without known immunological, renal or central nervous system dysfunction were enrolled in the study. Patients with pre-existent congestive heart failure, exogenous hormone therapy, chronic renal failure, malignancy past and present, infection, inflammation, myocardial infarction within 6 weeks, malnutrition or with diabetes mellitus type I were excluded from this study. The enrolees were divided according to their age into two study groups: group 1 with seven patients < 50 years old and group 2 with seven patients > 65 years old (Table 2). All patients suffered from angina pectoris due to documented arterosclerosis. Three patients in group 2 and one patient in group 1 had a history of myocardial infarction in the past. Five patients in group 1 and three patients in group 2 suffered from hyperlipidaemia. Three patients in group 1 and five patients in group 2 were hypertensive. Three patients in group 1 had well controlled diabetes mellitus type II.

Table 2.

Mean values, s.d. and the results of the power analysis of the measured cytokines for both age groups

Study design

Premedication consisted of oral flunitrazepam 1 mg on the evening of surgery and on call to the operating room (OR). Induction of anaesthesia was achieved by administering midazolam 0.05 mg/kg, sufentanil 1 μg/kg, and etomidate 0.2 mg/kg. Endotracheal intubation was performed following relaxation with pancuronium 0.1 mg/kg. Anaesthesia was maintained with continuous infusions of sufentanil 0.1 μg/kg per h and midazolam 0.03 mg/kg per h. Endtidal concentrations of isoflurane were titrated between 0.4 vol% and 0.8 vol% according to the clinical situation. Repetitive doses of pancuronium 0.03 mg/kg were given on an hourly basis to maintain adequate neuromuscular blockade. Controlled mechanical ventilation (CMV) using an air in oxygen mixture with an inspired oxygen concentration (FIO2) between 0.33 and 1.0 was instituted, to keep the arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) > 100 mmHg. In normovolaemic patients, arterial hypotension (mean arterial pressure (MAP) of < 70 mmHg) was treated with a dopamine infusion at 2–5 μg/kg per min. Hypertension (systolic pressures > 140 mmHg) was treated with a nitroglycerin infusion at 1–2 μg/kg per min. Following surgery, all patients remained intubated and artificially ventilated in the intensive care unit (ICU) until they regained sufficient spontaneous respiration. During this time, the sufentanil infusion was continued for sedation at 0.01–0.02 μg/kg per h. All extubations took place upon stable cardiovascular and respiratory conditions of the patients.

During the period of data sampling, patients received no medication containing steroids.

Cardiopulmonary bypass

CPB was conducted using a membrane oxygenator (Stöckert Instruments, Mutz an der Knatter, Germany) employing moderate hypothermia (28–32°C) and non-pulsatile flow. Pump prime consisted of 1000 ml Ringer's solution, 250 ml human albumin 5% and 250 ml mannitol solution 20%. Pump flow was maintained at 2.4 l/m2 body surface area (BSA) per min. Saint Thomas' Hospital crystalloid cardioplegic solution (600 ml) was injected in the aortic root immediately after cross-clamping of the aorta to achieve cardiac arrest.

Additional cardioplegia was administered in 200-ml increments every 30 min to maintain cardiac stand still.

Blood samples

Time and route of collection of blood samples were as follows. Pre-operatively between 6 and 8 p.m., before premedication (T1); intra-operatively 90 min after incision, on bypass, between 9.00 a.m. and 15.00 p.m. (T2); and post-operatively between 6 and 8 p.m. on the day of surgery (T3), as well as between 6 and 8 p.m. on the first post-operative day (T4).

Blood samples were obtained from an i.v. sampling catheter. The blood was spun down for 10 min in a centrifuge at 1500 rev/min and −10°C 10 min after drawing. The serum was stored at −80°C until it was assayed. Since most of our CABG patients leave the hospital on the second or third post-operative day to undergo cardiac rehabilitation programmes elsewhere, blood sampling was restricted to post-operative day 1.

Cytokine determinations

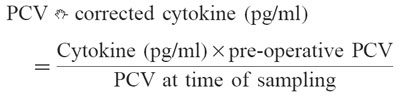

The concentrations of the cytokines IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α and sIL-2R were measured in a quantitative sandwich ELISA. For our investigations we used commercial kits only (Quantikine; R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK). The calculation of the cytokine values was performed as a relative measurement in comparison with standards that are aligned with World Health Organization references. Assays were repeated from the identical frozen specimen if the obtained values were out of range. In order to take perioperative plasma volume changes into account, blood sampling for cytokine and packed cell volume (PCV) was performed simultaneously. Correction of the dilution effect for cytokine determinations in regard to PCV was made according a formula that was described by Taylor et al. [23]:

|

According to information from the manufacturer, sensitivities for the assays were: TNF-α < 180 fg/ml, IL-6 assay = 0.70 pg/ml, IL-1β assay < 100 fg/ml, and sIL-2R assay = 24 pg/ml. Intra-assay coefficients were 5.6–6.1% for TNF-α, 8.0–11.8% for IL-1β, 3.2–8.5% for IL-6, 4.6–6.1% for IL-2R and 2.3–7.5% for IL-10 assay. Interassay coefficients were 7.5–10.4% for TNF-α, 7.1–11.1% for IL-1β, 3.5–8.7% for IL-6, 6.0–7.2% for IL-2R, 3.7–7.6% for IL-10.

For IL-10 blood samples were assayed with use of an ultrasensitive sandwich-type ELISA (Cytoscreen; Laboserv GmbH Diagnostica, Giessen, Germany). The lower limit of quantification was quoted as < 208 fg/ml.

Statistical analysis

We used the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for analysing data. The PCV-corrected immunological data were not normally distributed (Kolmogorow–Smirnow test). Data are presented as the mean and s.d.

The immunological parameters were statistically evaluated by non-parametric two-way analysis of variance (Friedman test). Post hoc comparisons were done by Wilcoxon tests.

The study group was divided into two groups according to age. Pair-wise comparisons among both groups were done by Mann–Whitney U-test. The significance level was set to α < 0.05.

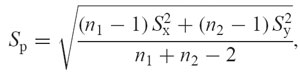

Power analysis of the data was performed with NQuery [24]. A sample size of Nestim in each group will have 80% power to detect the difference between the mean of group 1 (μ1) and group 2 (μ2) assuming that the common s.d.

|

using a two-group t-test with a 0.050 two-sided significance level (see Table 2).

RESULTS

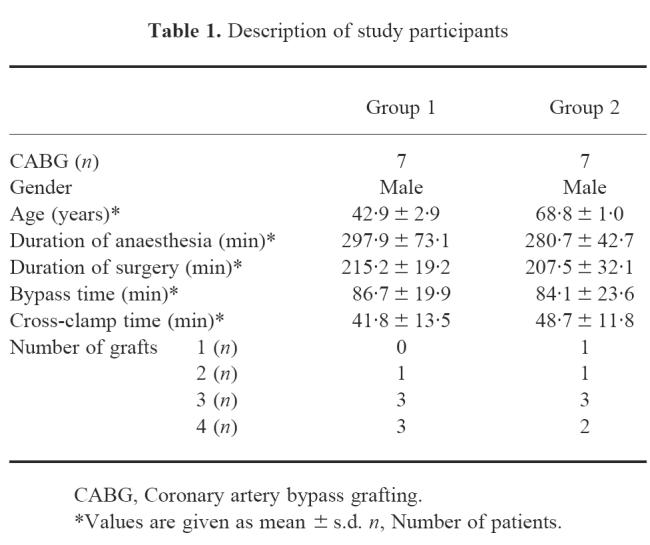

Serum concentrations of IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-10 and sIL-2R of patients < 50 years old (group 1) and > 65 years old (group 2) undergoing elective CABG surgery were determined on four data points during the perioperative period. Descriptions of the study participants, number of grafts performed during surgery, as well as duration of anaesthesia, surgery, bypass and cross-clamp times for the two age groups are listed in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the age groups in duration of anaesthesia, surgery, bypass and cross-clamp times.

Table 1.

Description of study participants

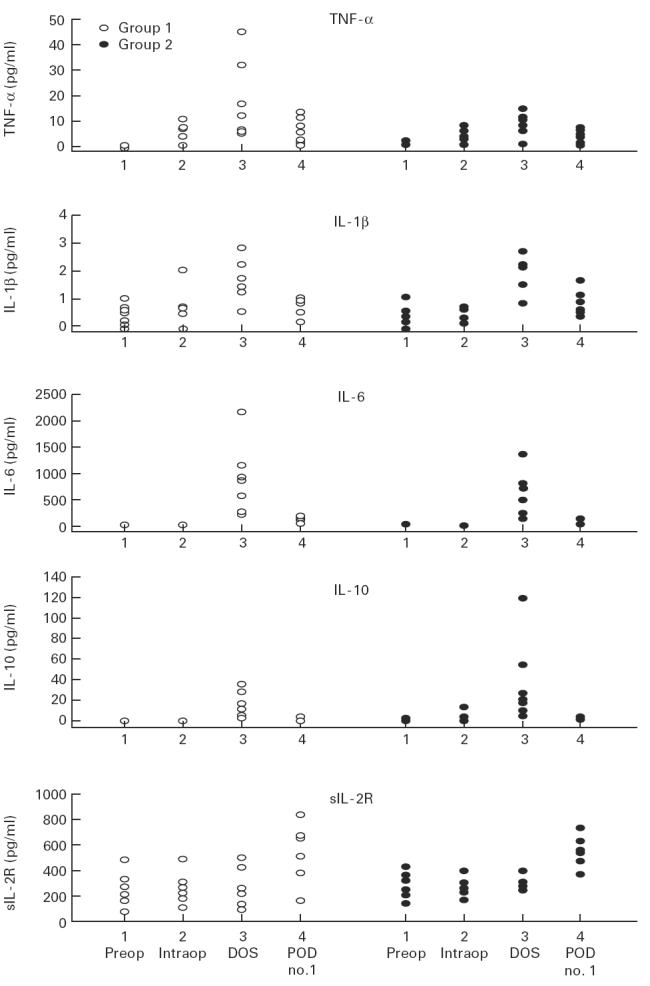

IL-6, TNF-α, and sIL-2R were detected in all patients during the measurement period. Pre- and intra-operatively, IL-1β was detected in 12 of the 14 patients, post-operatively (T3, T4) in all patients. IL-10 was detected pre-operatively (T1) in one, intra-operatively (T2) in two, post-operatively (T3) in all, and on the first post-operative day (T4) in three patients of the study group. Table 2 demonstrates the obtained parameters of the investigated age groups as mean and s.d. Figure 1 depicts the individual values of the measured cytokines for both groups. When comparing pre-operative with post-operative values, samples drawn at T3 showed significant increases of serum levels for IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-10 amongst both groups (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Perioperative alterations in concentrations of circulating tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10 and sIL-2R in patients < 50 years old (group 1) versus patients > 65 years old (group 2) undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. 1, Pre-operative; 2, intra-operative; 3, post-operative on day of surgery; 4, post-operative, on the first post-operative day.

Measurements taken at T4 demonstrated a significant increase of sIL-2R compared with pre-operative values in both groups. Blood concentrations of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10 and sIL-2R at the four data points during the perioperative period in patients > 65 years old were not significantly different compared with patients < 50 years old.

A power analysis was performed to estimate the number of patients to detect significant differences in cytokine levels amongst both age groups. Table 2 shows the results of the power analysis: the sample size in each group (Nestim) that is necessary to deem a given difference significant and the amount of power in percentage (% power) in our study test with n = 7.

The sample size of seven in each group has 27% power to detect the difference in means for IL-6 pre-operatively of − 1.586 (the difference between the group 1 mean of pre-operative IL-6, μ1, of 2.071 and the group 2 mean, μ2, of 3.657) assuming that the common s.d. is 2.000 using a two-group t-test with a 0.050 two-sided significance level.

DISCUSSION

This study compares the perioperative blood levels of IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-10 and sIL-2R in male patients undergoing elective CABG surgery according to the patients' ages.

The release of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α as well as the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 and sIL-2R were not significantly different in the group of patients < 50 years old compared with the patients > 65 years old.

Post-operatively on the day of surgery, the mean of IL-10 in the older age group was slightly higher than in the younger age group. IL-10 is known to have anti-inflammatory properties [25–28]. IL-10 inhibits the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and reduces antigen-specific human T cell proliferation by diminishing the antigen-presenting capacity of monocytes [29]. Our result is in accordance with the finding of Meyer et al. [30], who investigated IL-10 concentrations in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid among different age groups. However, without reaching statistical significance, in patients > 65 years old Meyer et al. found overall higher levels of IL-10 as well as increased detection of IL-10.

Although none of the measured cytokines differed between the age groups to a statistically significant extent, the means of IL-6 and TNF-α were higher in the younger group.

Several studies reported an increased unstimulated and stimulated IL-6 in elderly animals and human beings [30–33]. Fagiolo et al. [15] reported that the in vitro production of IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α by peripheral mononuclear cells was increased in older subjects. These results are in contrast to others, which found no age related differences in IL-10 [30], TNF-α [34,35] or IL-6 secretion [34,36]. Caruso et al. [34] found no significant difference between elderly and young subjects in regard to TNF-α, IL-4, IL-5 and IL-6 secretion. Recent publications further reported that in the healthy elderly, immune responses are not impaired and resemble adult immune responses [37–39].

Several studies have shown that not biological age but additional risk factors, e.g. hypertension, diabetes mellitus and myocardial infarction, are responsible for the increased risk during surgery in the elderly [40]. These studies showed that incremental risk factors for morbidity in the elderly are a higher New York Heart Association (NYHA) class, congestive heart failure, emergency surgery and female gender [40]. In order to achieve homogen study conditions, only men undergoing elective procedures were enrolled.

The SENIEUR selection protocol is a benchmark method for studying age effects in healthy elderly subjects [41,42]. Our study on patients undergoing CABG surgery, who are less healthy than subjects selected according to SENIEUR protocol, may constitute a population in which it is important to assess dysregulated immune function for its clinical relevance [38]. It can not be fully excluded that differences in concomitant diseases between the patient groups may have confounded the differences that have been related to age alone. Several studies described relationships between cytokine release and disease, e.g. diabetes mellitus [43–45], hyperlipidaemia [46]. Furthermore, age-related abnormalities in cytokine secretion may not be only ‘cytokine-specific’ but also ‘stimulus-specific’ [35].

The used anaesthetic technique is a common combination of anaesthetic agents in cardiac surgery [47–49]. Many of the drugs used perioperatively are assumed to influence cytokine release, but their specific and additive effects are not yet well characterized.

In a recent study Taylor et al. [50] showed that the inflammatory response to surgery measured by cytokines is not modified by the supplementation of potent agents (such as isoflurane) combined with conventional dosages of opioids. However, the administration of isoflurane alone inhibited the release of IL-1β and TNF-α by human peripheral mononuclear cells [51]. Brand et al. [52] detected anaesthesia-associated increase of TNF-α, sIL-2R synthesis after in vitro stimulation of immune cells with mitogens, while IL-1β and IL-6 remained unchanged during general anaesthesia by fentanyl, thiopental and isoflurane. Midazolam causes an increase in the production of TNF-α from human monocytes [53]. Other drugs (mannitol, ACE inhibitors, aprotinin, hetastarch, heparin, protamine) given during CABG surgery may modulate the balance of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines. In a study by McBride et al. [54] the cytokine response of in vitro monocyte cultures was studied in relation to the administration of drugs commonly used in cardiac surgery. IL-1β was increased by heparin. Fentanyl enhanced the IL-1 receptor antagonist response. Protamine blocked the heparin-induced increase in TNF-α and IL-1β. Opiates were able to modulate IL-6 response in rats [55]. Crozier et al. [56] and Pirttikangas et al. [57] found an attenuation of IL-1β release by opiates. From the above described studies it is evident that study designs that model surgical stimulus and anaesthetic effect vary greatly.

Factors that may have influenced the perioperative immunological response, such as type of anaesthesia and type of surgery, were kept constant between the two study groups.

Our results may indicate that there is no significant difference in cytokine secretion in differently aged patients undergoing CABG surgery. Although statistically not significant, our data show higher mean values in the younger group, making it more likely that other concomitant factors (e.g. disease process) and not age per se evokes differences of cytokine release. Several factors may account for our findings: patients undergoing CABG surgery may represent a subset of elderly patients with a certain pattern and extent of concomitant disease that is not equal to the possibly more diverse health status of medically treated geriatric patients that were enrolled in the above cited studies [38]. The impact of age alone on perioperative cytokine release may have not been captured accurately by our small sample size and the inability to enrol patients at greater extremes of age. It can not be excluded that studies with a greater number of patients and/or studies with a higher age differential in the study groups may find age-related differences in perioperative cytokine release.

We conclude from our results that in patients with comparable anaesthesiological as well as surgical management the cytokine release of elderly patients (> 65 years) is not significantly different from younger patients (< 50 years) in the perioperative course of CABG surgery up to the first post-operative day. Further studies that have a greater sample size as well as account for the extremes of age are necessary to understand the full scope of immunological response to CABG surgery during senescence.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mrs Bianca Sternberg (Institute of Immunology and Transfusion Medicine, Medical University of Lübeck) for the processing of the cytokine assays, Professor Dr H. H. Sievers, Chairman of the Department of Cardiac Surgery, who gave permission to perform the study in his Department, PD Dr H. J. Friedrich, Associate Professor of Biomedical Statistics, for his help with the statistical analysis of the data.

REFERENCES

- 1.Herskowitz A, Mangano DT. Inflammatory cascade. A final common pathway for perioperative injury? Anesthesiology. 1996;85:957–60. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199611000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Downing SW, Edmunds LH. Release of vasoactive substances during cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thor Surg. 1992;54:1236–43. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(92)90113-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hattler BG, Finkel MS. Interleukin-6, a myocardial depressant factor and its possible role in myocardial reperfusion injury in man. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 1991;15F:145. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lahat N, Zlotnick AY, Shtiller R, Bar I, Merin G. Serum levels of IL-1, IL-6 and tumour necrosis factors in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafts or cholecystectomy. Clin Exp Immunol. 1992;89:255–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb06941.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hattler BG, Zeevi A, Oddis CV, Finkel MS. Cytokine induction during cardiac surgery: analysis of TNF-α expression pre- and postcardiopulmonary bypass. J Card Surg. 1995;10(Suppl.):418–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.1995.tb00671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shimada M, Winchurch RA, Beloucif S, Robotham JL. Effect of anesthesia and surgery on plasma cytokine levels. J Crit Care. 1993;8:109–16. doi: 10.1016/0883-9441(93)90015-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paganelli R, Scala E, Quinti I, Ansotegui IJ. Humoral immunity in aging. Aging Clin Exp Res. 1994;6:143–50. doi: 10.1007/BF03324229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirokawa K. Understanding the mechanism of the age-related decline in immune function. Nutr Rev. 1992;50:361–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1992.tb02481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song L, Kim YH, Chopra RK, et al. Age-related effects in T cell activation and proliferation. Exp Geront. 1993;28:313–21. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(93)90058-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thoman ML, Weigle WO. The cellular and subcellular bases of immunosenescence. Adv Immunol. 1989;46:221–61. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60655-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hallgren HM, Buckley CE, Gilbersten VA, et al. Lymphocyte phytohemagglutinin responsiveness, immunoglobulins and autoantibodies in aging humans. J Immunol. 1973;124:1101–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lehtonen L, Eskols J, Vainio O, et al. Changes in lymphocyte subsets and immune competence in very advanced age. J Gerontol. 1990;45:M108–M112. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.3.m108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sansoni P, Cossarizza A, Brianti V, et al. Lymphocyte subset and natural killer cell activity in healthy old people and centenarians. Blood. 1993;82:2767–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei J, Xu H, Davies JL, Hemming GP. Increase of plasma IL-6 concentration with age in healthy subjects. Life Sci. 1992;51:1953–6. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fagiolo U, Cossarizza A, Scala E, et al. Increased cytokine production in mononuclear cells of healthy elderly people. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:2375–8. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rabinowich H, Goses Y, Reshef T, et al. Interleukin-2 production and activity in aged humans. Mech Ageing Dev. 1985;32:213–26. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(85)90081-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molteni M, Bella SD, Mascagni B, et al. Secretion of cytokines upon allogeneic stimulation: effect of aging. J Biol Reg Homeos Ag. 1994;8:41–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sindermann J, Kruse A, Frercks HJ, et al. Investigations of the lymphokine system in elderly individuals. Mech Ageing Dev. 1993;70:149–59. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(93)90066-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tracey KJ, Beutler B, Lowry SF, et al. Shock and tissue injury by recombinant human cachectin. Science. 1986;234:470–4. doi: 10.1126/science.3764421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okusawa S, Gelfand JA, Ikejima T, Connolly RJ, Dinarello CA. Interleukin 1 induces a shock-like state in rabbits. J Clin Invest. 1988;81:1162–72. doi: 10.1172/JCI113431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finkel MS, Oddis CV, Jacob TD, Watkins SC, Hattler BG, Simmons RL. Negative inotropic effects of cytokines on the heart mediated by nitric oxide. Science. 1992;257:387–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1631560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hennein HA, Ebba H, Rodriguez JL, et al. Relationship of the proinflammatory cytokines to myocardial ischemia and dysfunction after uncomplicated coronary revascularization. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;108:626–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor KM, Bain WH, Jones JV, Walker MS. The effect of hemodilution on plasma levels of cortisol and free cortisol. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1976;72:57–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elashoff JD. Los Angeles: Dixon Associates; 1995. NQuery advisor user's guide. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marchant A, Bruyns C, Vandenabeele P, et al. Interleukin-10 controls interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor production during experimental endotoxemia. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:1167–71. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marchant A, Devière J, Byl B, De Groote D, Vincent JL, Goldman M. Interleukin-10 production during septicaemia. Lancet. 1994;343:707–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91584-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Vries JE. Immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory properties of interleukin 10. Ann Med. 1995;27:537–41. doi: 10.3109/07853899509002465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katsikis PD, Chu CQ, Brennan FM, Maini RN, Feldmann M. Immunoregulatory role of interleukin 10 in rheumatoid arthritis. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1517–27. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.5.1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Waal Malefyt R, Haanen J, Spits H, et al. Interleukin 10 (IL-10) and viral IL-10 strongly reduce antigen-specific human T cell proliferation by diminishing the antigen-presenting capacity of monocytes via downregulation of class II major histocompatibility complex expression. J Exp Med. 1991;174:915–24. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.4.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyer KC, Ershler W, Rosenthal NS, Lu XG, Peterson K. Immune dysregulation in the aging human lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:1072–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.3.8630547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ershler WB. Interleukin-6: a cytokine for gerontologists. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;176:176–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb02054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ershler WB, Sun WH, Binkley N, et al. Interleukin-6 and aging: blood levels and mononuclear cell production increase with advancing age and in vitro production is modifiable by dietary restriction. Lymphokine Cytok Res. 1993;12:225–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Daynes RA, Araneo BA, Ershler WB, Maloney C, Li GZ, Ryu SY. Altered regulation of IL-6 production with normal aging. Possible linkage to the age-associated decline in dehydroepiandrosterone and its sulfated derivative. J Immunol. 1993;150:5219–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caruso C, Candore G, Cigna D, et al. Cytokine production pathway in the elderly. Immunol Res. 1996;15:84–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02918286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riancho JA, Zarrabeitia MT, Amado JA, Olmos JM, González-Macias J. Age-related differences in cytokine secretion. Gerontology. 1994;40:8–12. doi: 10.1159/000213568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Candore G, Di Lorenzo G, Melluso M, et al. γ-interferon, interleukin-4 and interleukin-6 in vitro production in old subjects. Autoimmunity. 1993;16:275–80. doi: 10.3109/08916939309014646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rowe JW, Kahn RL. Human aging: usual and successful. Science. 1987;237:143–9. doi: 10.1126/science.3299702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pawelec G, Adibzadeh M, Pohla H, et al. Immunosenescence: ageing of the immune system. Immunol Today. 1995;16:420–2. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peterson PK. Aging, immunity, and cardiopulmonary bypass surgery: adding insult to injury. J Lab Clin Med. 1997;129:578–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(97)90190-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fernandez J, Chen C, Anolik G, et al. Perioperative risk factors affecting hospital stay and hospital costs in open heart surgery for patients > or =65 years old. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1997;11:1133–40. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(97)01216-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ligthart GJ, Corberand JX, Geertzen HG, et al. Necessity of the assessment of health status in human immunogerontological studies: evaluation of the SENIEUR protocol. Mech Ageing Dev. 1984;55:89–105. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(90)90108-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ligthart GJ, Radl J, Corberand JX, et al. Monoclonal gammopathies in human aging: increased occurrence with age and correlation with health status. Mech Agein Dev. 1990;52:243–53. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(90)90127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feugeas JP, Caillens H, Charron D, et al. Influence of metabolic and genetic factors on tumor necrosis factor alpha and lymphotoxin-alpha production in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Diabet Metab. 1997;23:295–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hussain MJ, Peakman M, Gallati H, et al. Elevated serum levels of macrophage-derived cytokines precede and accompany the onset of IDDM. Diabetologia. 1996;39:60–69. doi: 10.1007/BF00400414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chang FY, Shaio MF. Decreased cell-mediated immunity in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pr. 1995;28:137–46. doi: 10.1016/0168-8227(95)00168-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Terao K, Fukase Y. Effects of hyperlipaemic serum on interleukin-2 (IL-2) production, IL-2 receptor expression and T cell proliferation induced by IL-2 in cynomolgus monkeys. Jpn J Med Sci Biol. 1991;44:17–28. doi: 10.7883/yoken1952.44.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roth-Isigkeit A, Brechmann J, Dibbelt L, et al. Persistent endocrine stress response in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. J Endocrinol Invest. 1998;21:12–19. doi: 10.1007/BF03347280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Raza SMA, Masters RW, Vasireddy AR, Zsigmond EK. Haemodynamic stability with midazolam-sufentanil analgesia in cardiac surgical patients. Can J Anaesth. 1988;35:518–25. doi: 10.1007/BF03026904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tuman KJ, McCarthy RJ, El-Ganzouri AR, et al. Sufentanil-midazolam anesthesia for coronary artery surgery. J Cardiothorac Anaesth. 1990;4:308–13. doi: 10.1016/0888-6296(90)90036-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taylor NM, Lacoumenta S, Hall GM. Fentanyl and the interleukin-6 response to surgery. Anaesthesia. 1997;52:112–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1997.65-az0063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mitsuhata H, Shimizu R, Yokoyama MM. Suppressive effects of volatile anesthetics on cytokine release in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1995;17:529–34. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(95)00026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brand JM, Kirchner H, Poppe C, et al. The effects of general anaesthesia on human peripheral immune cell distribution and cytokine production. Clin Immunol Immunopharmacol. 1997;83:190–4. doi: 10.1006/clin.1997.4351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rossano F, Tufano R, Cipollaro-de-Lèro G, et al. Anesthetic agents induce human mononuclear leucocytes to release cytokines. Immunopharmacol Immunother. 1992;14:439–50. doi: 10.3109/08923979209005403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McBride WT, Armstrong MA, McMurray TJ. An investigation of the effects of heparin, low molecular weight heparin, protamine and fentanyl on the balance of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in in-vitro monocyte cultures. Anaesthesia. 1996;51:634–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1996.tb07844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bertolucci M, Perego C, De-Simoni MG. Central opiate modulation of peripheral IL-6 in rats. Neuroreport. 1996;7:1181–4. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199604260-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Crozier TA, Müller JE, Quittkat D, et al. Effect of anaesthesia on the cytokine responses to abdominal surgery. Br J Anaesth. 1994;72:280–5. doi: 10.1093/bja/72.3.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pirttikangas CO, Salo M, Mansikka M, et al. The influence of anaesthetic technique upon the immune response to hysterectomy. Anaesthesia. 1995;50:1056–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1995.tb05951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]