Abstract

Infants respond to antigen by making antibody that is generally of low affinity for antigen. Somatic hypermutation of immunoglobulin genes, and selection of cells expressing mutations with improved affinity for antigen, are the molecular and cellular processes underlying the maturation of antibody affinity. We have reported previously that neonates and infants up to 2 months of age, including individuals undergoing strong immunological challenge, show very few mutated VH6 sequences, with low mutation frequencies in mutated sequences, and little evidence of selection. We have now examined immunoglobulin genes from healthy infants between 2 and 10 months old for mutation and evidence of selection. In this age group, the proportion of VH6 sequences which are mutated and the mutation frequency in mutated sequences increase with age. There is evidence of selection from 6 months old. These results indicate that the process of affinity maturation, which depends on cognate T–B cell interaction and functional germinal centres, is approaching maturity from 6 months old.

Keywords: somatic hypermutation, antibody response, paediatric immunology, affinity maturation, immunoglobulin genes, VH6

INTRODUCTION

The immune response of neonates is functionally immature [1–3]. The infant makes largely IgM antibody, of low affinity, and against a limited range of antigens [1,4,5]. The development of immunological memory appears to be restricted, as illustrated by lower recall responses to some antigens in infants immunized at 7 days old compared with infants immunized later [6]. The capacity to develop memory is, however, established at least in part by 4 months old, since immunization with polysaccharide–protein conjugates at this age induces a state of memory, such that later antigen exposure elicits a secondary response [7].

We have shown that the neonate and infant up to 2 months old is capable of mutating immunoglobulin genes, but the frequency of mutated clones, as well as the frequency of mutations in mutated clones, is very low compared with adults [8]. Furthermore, there is limited evidence of selection [8]. Klein et al. [9] showed in a sample from a 4-year-old child that mutations were present at a high rate in tonsil germinal centre cells and at a lower rate in peripheral blood B cells. van DijkHard et al. [10] compared four cord blood samples with adults ranging from 21 years old upwards, and found a lower rate of mutation and selection in cord blood. The capacity of the immune system to engage in mutation and selection in the age group 2–10 months is unknown, although this age group is the major recipient of prophylactic immunization. Immunization is effective as a means of preventing infectious disease in infancy, but our understanding of the immune response in the human infant is limited, and a better understanding could lead to improvements in immunization procedures. In this study we investigate whether the immune response of the infant aged 2–10 months is mature with regard to immunoglobulin gene mutation frequency and selection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Samples

Peripheral blood samples (≈ 300 μl) were obtained from healthy uninfected infants who were enrolled in an immunization trial, and from adult laboratory staff. Informed consent was obtained in all cases and samples were taken by arterial catheter. All blood samples were anticoagulated with lithium heparin (15 U) The studies were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Women's and Children's Hospital, working under the principles of the Helsinki declaration.

Preparation of cells

Mononuclear cell fractions were isolated by density centrifugation on Lymphoprep (Nycomed Pharma, Oslo, Norway). Blood samples were centrifuged at 350 g for 4 min in a microfuge and the mononuclear cell layer was collected and washed with PBS (3800 g for 2 min).

Genomic DNA extraction

Genomic DNA was prepared from the mononuclear cell fraction using the Dynabeads DNA Direct Kit (Dynal, Oslo, Norway). DNA was resuspended in 20–30 μl of 10 mm Tris–HCl pH 8 and stored at 20°C.

Amplification and cloning of rearranged VH6–D–JH genes

A two-round polymerase chain reaction (PCR) protocol was used to amplify genomic VH6–D–JH rearrangements, as described previously [8]. Second-round amplified DNA was purified, ligated into the pGem-T vector (Promega, Madison, WI) and used to transform competent Escherichia coli TG1 cells. Recombinant colonies were selected by blue/white screening and screened for the presence of VH6 insert as described previously [8].

Heteroduplex analysis of cloned VH6 DNA

Amplified cloned VH6 DNA (5 μl) was mixed with unmutated VH6 DNA (5 μl) which had been amplified with identical primers (VH6-ND and FWR3-anti). The presence of heteroduplexes was analysed on polyacrylamide gel as described previously [8].

Analysis of VH6–D–JH sequences

Clones which appeared mutated by heteroduplex analysis were sequenced as described previously [8]. Sequences were compared with the germ-line VH6 sequence 6-1G1 [11] using the IBI MacVector software (Kodak, Rochester, NY), and point mutations were identified.

Estimation of fidelity of PCR amplification

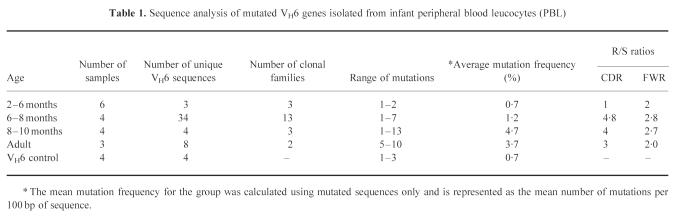

Using the above methods, four unmutated VH6–D–JH rearrangements were amplified and cloned. VH6+ clones were screened by heteroduplex analysis. Between 6% and 9% of the clones showed mutations (Fig. 2). Sequencing of these mutated clones revealed mutations from a single base deletion up to three mutations per clone. The mean mutation frequency was 1.75 mutations/clone (0.7%) (Table 1).

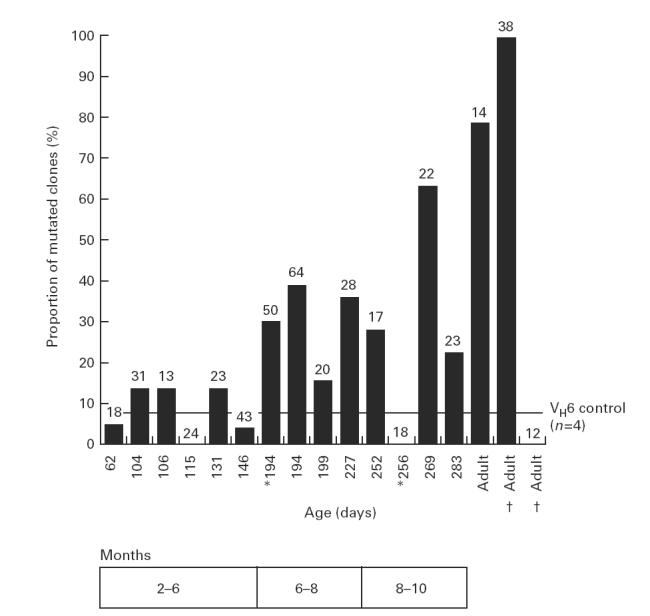

Fig. 2.

Summary of heteroduplex analysis of VH6 sequences isolated from cloned samples. Each bar represents the percentage of mutated sequences detected for each sample. The total number of VH6 sequences analysed is given above each bar. The VH6 control line represents the proportion of mutated sequences which arise from polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification, and is the mean value from four separate cloning reactions of a germ-line VH6–D–J rearrangement and the subsequent screening of 125 VH6+ clones. Sequential blood samples taken from the same donor are shown by † or *.

Table 1.

Sequence analysis of mutated VH6 genes isolated from infant peripheral blood leucocytes (PBL)

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance of the difference between two groups in proportion to sequences showing mutations was assessed using Fisher's exact test (two-tailed). The relationship between age and occurrence of mutation was examined by linear regression analysis. Mutation frequencies in individual samples were compared using the Mann–Whitney U-statistic. Values of P < 0.05 were considered to show statistical significance.

Analysis of adult sequences from database

A database of existing VH6-containing adult immunoglobulin sequences was assembled by extracting sequences from the GenBank database (21 August 1997 release). Sequences identical to the germ-line were excluded, leaving 107 sequences containing mutations. These sequences were aligned to the germ-line VH6 sequence using MacVector software and the frequency of mutations determined. Only the regions for which complete sequences were available were included in calculations of mutation frequencies and replacement/silent (R/S) ratios. The region analysed was the same 241-bp region analysed in our samples.

RESULTS

Proportion of VH6 sequences with mutations

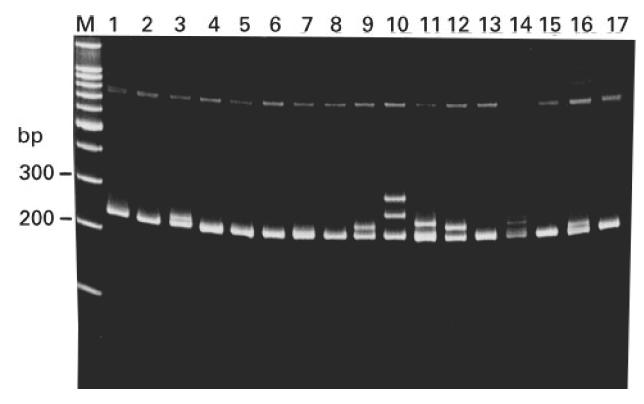

Amplified VH6 genomic DNA from 14 infants aged 2–10 months was cloned and mutated sequences were identified by heteroduplex analysis. Figure 1 shows a representative gel with heteroduplexes formed between mutated and unmutated VH6 DNA. Figure 2 plots the proportion of mutated clones against age. The proportion of sequences bearing mutations was low up to 6 months old (mean = 9%) and was not significantly different from the proportion of mutated clones in the VH6 control (P = 1). In the 6–8 and 8–10 month age groups the proportion of sequences showing mutations was significantly higher than in controls (P < 0.05) and reached levels close to and greater than 30%, still lower than adults (generally > 80%). In three samples (Fig. 2), one of them an adult, no mutated clones were found. In the adult a later sample, and in one of the infants an earlier sample, showed mutations. Regression analysis showed that, for infants 2–10 months old, there was a correlation between age and the proportion of sequences showing mutation (R = 0.55; P = 0.042) There was a significant difference (P < 0.05, Fisher's exact test) between the 2–6 month and 6–8 month age groups, while the difference between the 6–8 month and 8–10 month groups was not significant. The proportion of mutated clones for all infant age groups was significantly different from the adult group (P < 0.05, Fisher's exact test).

Fig. 1.

Heteroduplex analysis of VH6+ clones isolated from infant peripheral blood leucocytes (PBL). Mutated clones were identified by heteroduplex formation (lanes 3, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14) between the unknown VH6 sequence and a known germ-line VH6 sequence (run unmixed in lane 15). Mutations were confirmed by sequencing. Heteroduplex negative clones were considered unmutated (lanes 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 13), and some of these were also sequenced to confirm this. A positive control (lane 16) of germ-line mixed with mutated VH6 sequence (two mutations) showed a double band. M, Marker lane (100-bp ladder; Promega).

Mutation frequency in mutated VH6 sequences

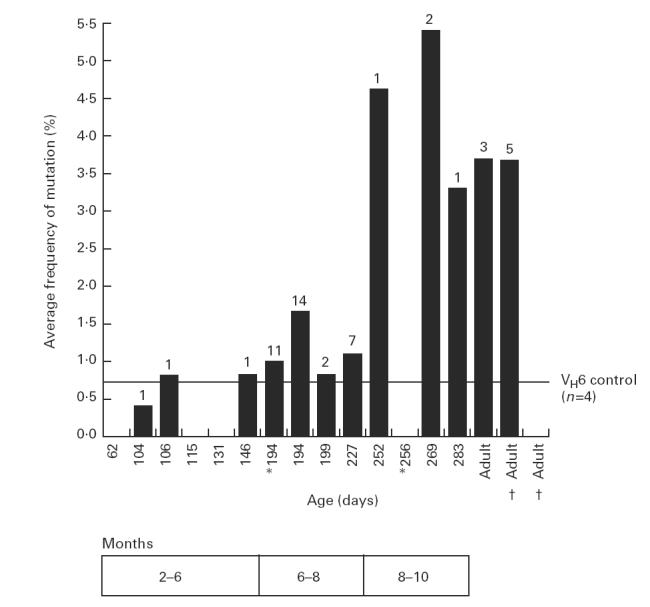

To avoid sequencing identical clones, mutated clones were first screened against each other by heteroduplex analysis; sequencing was performed only on clones which differed according to heteroduplex formation. For each blood sample, the mean frequency of mutations per mutated sequence was calculated; the mean values (expressed as mutations per 100 bp of sequence) are plotted against age in Fig. 3. Infants < 8 months old did not show significantly higher mutation frequencies than the VH6 control (P > 0.05, Mann–Whitney U-test). From 8 months old the mean mutation frequency was significantly higher than in the VH6 control (P < 0.05) and comparable to adults. Table 1 summarizes the results pooled into age groups.

Fig. 3.

Sequence analysis of the mutated VH6 genes isolated from infant and adult peripheral blood leucocytes (PBL). Each bar represents the mean mutation frequency, for the mutated sequences, for a particular sample. Mutation frequency is expressed as the mean number of mutations per 100 bp of sequence. The numbers above the bar represent the number of unique mutated sequences isolated for each sample. The VH6 control line represents the mean mutation frequency from mutated clones generated by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) protocol. Sequential blood samples taken from the same donor are shown by † or *. We were unable to obtain satisfactory sequencing data for those mutated clones detected in infants aged 62 and 131 days, hence no mutation frequency is shown for these samples.

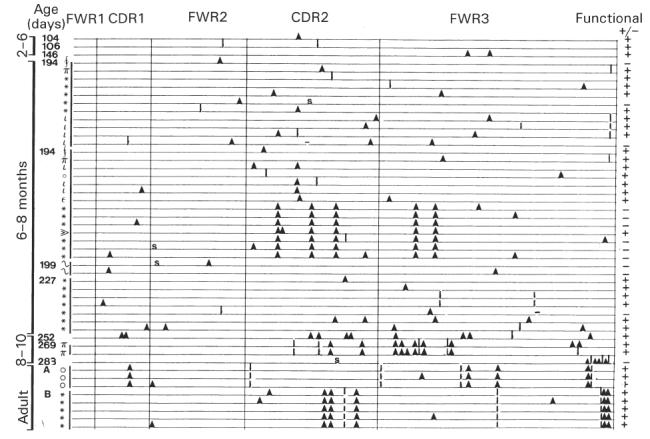

Selection and intraclonal diversification

Figure 4 shows the mutations that were identified in 49 mutated sequences analysed from infants and adults. In the 6–8 month group there were, in addition to the 22 functional rearrangements, 12 non-functional rearrangements. These non-functional sequences provided an additional 26 mutations from five clonal families (a clonal family being a group of non-identical sequences with the same CDR3). One clonal family (labelled 194* in Fig. 4) yielded six different sequences which shared five mutations and expressed up to three additional unique mutations. This suggests that the cells went through several rounds of mutation and may have been subjected to selection before acquiring disabling mutations. This non-functional clonal family also shared the same five mutations with a different (functional) clonal family isolated from the same sample, suggesting selection by a common antigen. In another clonal family five different mutated sequences were detected, containing up to four mutations, in addition to the germ-line sequence.

Fig. 4.

Schematic representation of mutations in rearranged VH6 sequences isolated from infants and adult blood samples. Each line represents one mutated VH6 sequence. The age of each infant is given in days on the left, with symbols denoting clonal families within each sample. The CDR and framework regions (FWR) are indicated and mutations are represented by different symbols: ▴, replacement mutations; I, silent mutations; S, stop codon; −, single base pair deletion. Functional sequences are represented by + and non-functional sequences arising from an altered reading frame or stop codons are shown as −.

The R/S ratios are shown in Table 1 for the CDR and framework region (FWR) for each of the age groups. In infants from 6 months upwards, R/S ratios for the CDR were comparable to those for adults.

CDR3 characteristics

The length of the CDR3 was examined. The CDR3 was defined as the region between the 3′ end of the VH6 sequence and the 3′ end of the J region (codon 95–102 inclusive), and identified by locating codons 92 and 102, which are highly conserved. CDR3 length varied between 24 and 60 bp (median 36) in the infant group, while the adult samples contained only two different CDR3 sequences, of 18 and 21 bp. Examination of the database of adult VH6 sequences showed CDR3 lengths ranging from 18 to 81 (median 36). The difference between the distributions (infant experimental data versus adult database) was not significant (Mann–Whitney U-test).

The major apparent difference in J gene usage was that 13/19 (68%) infant sequences used J4, compared with 35/82 (44%) in the adult database. This difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.05, Fisher's exact test). The major apparent differences in D region usage were the frequent use of DIR1 in infant sequences (3/19, 16%) compared with only 1/82 in adults, and the occurrence of DN1 as the most frequent D gene in adult sequences (17%) but in only 11% of infant sequences. These differences were not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The results of this study show an increasing incidence of mutation and selection with age in infants from 2 to 10 months. Heteroduplex analysis of cloned VH6 sequences showed a gradual increase with age in the proportion of mutated clones (Fig. 2), although the 8–10 month age group still showed a significantly lower proportion than the adult controls. Regression analysis showed a rise in mutation frequency with age (P < 0.05). The proportions of mutated clones in all groups > 6 months old were significantly different from the control unmutated sample, which represents the contribution from Taq polymerase-induced mutations. We previously analysed cord blood and infants up to 2 months old [8]. The majority of cord samples did not show mutations, but from the age of about 10 days infants with acute infection almost invariably had mutations, as detected by heteroduplex analysis of uncloned VH6 DNA [8]. Analysis of cloned VH6 rearrangements in the 10 days to 2 months age group in the earlier study revealed an incidence of mutated clones which was higher than in the 2–6 month age group in the current study (P = 0.024). However, the earlier study comprised infants in intensive care because of acute infection, while the children in the current study were healthy participants in an immunization trial. Furthermore, the 0–2 month age group included one individual with an exceptionally high load of mutations; if this sample is excluded from analysis the difference between the 0–2 and 2–6 month age groups becomes non-significant (P = 0.38).

In three samples no mutated clones were isolated, although they would have been expected on the basis of the age of the donor and the isolation of mutated sequences from other samples from the same donors. This probably reflects the sampling process, in the sense that the number of clones examined is limited and more importantly that the cells in the blood represent a limited sample of immune cells. Another consequence of sampling was the incidence of identical sequences isolated.

Mutated clones were sequenced in order to examine the process of mutation and selection in infants. The mutation frequency was low in infants < 6 months old (Table 1 and Fig. 3). Beyond 8 months old, the overall mutation frequency was 4.7%, comparable to that seen in adults (3.7% in our small adult sample and 4.3% in the larger database of 107 VH6 sequences derived from GenBank). As discussed above, in all cases the proportion of clones bearing mutations was lower in infants than in adults. The combination of adult frequencies of mutation in mutated clones with lower proportions of mutated clones, seen above 8 months of age, suggests that the mutational machinery is active but only a proportion of cells is involved. Mutation occurs primarily in germinal centres. These structures are seen in neonates, but there is as yet no detailed analysis to determine if they are fully active. The observations in this study are consistent with the possibility that a proportion of B cell proliferative activity occurs either outside germinal centres or in germinal centres which are not mutationally active, and that this proportion falls with increasing maturity.

VH6 was selected for analysis because it is a single-member gene family and avoids confusion between mutations and polymorphism. The question arises as to whether mutation in VH6 is atypical. VH6 has been reported to be used more frequently than would be expected from random V gene usage in the fetus [12], in ‘naturally activated’ B cells (cells which could be shown to contain immunoglobulin mRNA without in vitro activation) [13] and in autoreactive B cells [14]. VH6 is also used in responses to bacterial antigens, including Bordetella pertussis [15] and lipid A [16]. VH6 is used, and mutated, in CD5+ and CD5− B cells [17]. VH6 is the V region closest to the DJ genes, which may affect its usage. It is highly conserved in primates [18]. It has been suggested that VH6 may generate a binding site that is expanded on the basis of its unmutated structure rather than selected on the basis of mutation [10]. In contrast, Insel & Varade found VH6 to be highly mutated [19]. Our database analysis showed a mutation frequency of 4.3%, with a range from 1 to 24 mutations in the 241-bp segment analysed. Whilst VH6 may be atypical, cells with rearranged VH6 clearly are subject to mutation and selection and so provide a suitable probe for these processes in the infant immune system.

Insel & Varade [19] found that mutations were concentrated in the CDR, suggesting a mutation mechanism that favours the CDR. This observation confirms experimental studies in the murine model, which have defined the target of mutation as a region of 2 kb centred on the VDJ rearrangement, containing motifs which are particularly prone to mutation (hotspots) [20]. In the 41 sequences analysed from infants in the current study, the mutation frequency was also higher in the CDR (1.6%) than in the FWR (0.9%), a ratio similar to that found in the database sequences (6.4% for CDR and 3.3% for FWR).

The sequence data were examined for evidence of selection. Silent and replacement mutations are expected to be present in proportions reflecting random mutations in the absence of selection; deviations from the predicted frequency of silent and replacement mutations indicate the operation of selection processes. Since selection operates primarily on the CDR, the R/S ratio would be expected to be higher in the CDR than in the FWR if selection has been operative. Replacement mutations in the FWR often lead to loss of function [21], so the R/S ratio in the FWR tends to be lower in selected than unselected sequences. A general calculation based on codon redundancy indicates that the R/S ratio should be 2.9 in the absence of selection [22]. However, the probability of a silent or replacement mutation depends on the sequence itself, and a more detailed analysis on immunoglobulin gene mutations is based on knowledge of the germ-line sequence [23]. Based on mutation frequencies in unselected genes (in meiotic division), the 241-bp VH6 segment used in this study would be expected to give R/S ratios of 3.2 for CDR and 2.4 for FWR.

Predicted R/S ratios depend on the assumptions made, and Insel & Varade arrived at different predicted ratios (4.1 and 2.8) for VH6 CDR and FWR, respectively. For this reason, we have taken observed R/S ratios in the database for adult samples as the standard for comparison. Analysis of the 107 adult sequences in the database, which cover the same region as our samples, showed an R/S ratio of 3.7 for CDR and 1.7 for FWR. Combining the results for the 2–6 month age group in the present study with the 0–2 month samples described previously [8] yields R/S ratios of 2.1 for the CDR and 3.3 for the FWR, which does not suggest the operation of selection in these age groups. This does not rule out the possibility that selection operates in some individuals, and indeed one 15-day infant suffering cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection showed multiple mutations and an R/S ratio of 9 for the CDR compared with 2.3 for the framework [8].

In contrast, for the 6–10 month age group the R/S ratios were 4 for the CDR and 2.9 for the FWR, suggesting that selection was operating. In calculating the R/S ratios, shared mutations within clonal families were counted once, on the assumption that they arose from a single mutation event. Dual mutations in the same codon were counted as two replacement mutations if either alone would have led to a change; if they could be interpreted as one silent and one replacement mutation occurring separately they were counted as one of each.

Evidence of intraclonal diversification was seen in samples showing extensive mutation, including a 15-day-old infant [8] and some of the older infants. Intraclonal diversification was not evident in the majority of samples from infants < 6 months old, but this probably reflects the paucity of mutations. Since clonal diversification is believed to result from mutated/selected cells re-entering the mutation process in the germinal centre [21,24], this evidence supports the conclusion that germinal centres may operate normally from a young age, although the frequency of such events is low before 6 months old.

Examination of CDR length showed a wide range for both our infant population and an adult database population, and the distributions were not significantly different. Comparison of the CDR3 length in the different infant age groups did not reveal any significant difference. Whilst the distribution of CDR3 lengths in infants has not previously been compared with the corresponding parameter in adults, the literature contains analyses showing a longer CDR3 in the secondary repertoire (cells selected by antigen) compared with the primary (unselected) repertoire [25], and on the other hand an analysis of cord blood sequences showing longer CDR3 in IgM than in IgG or IgA sequences [26]. Our results show that CDR3 length can vary within approximately the same wide range in infants as in adults. Statistically significant differences were not observed in D and J gene usage between the infant (2–10 months old) population and the adult database population.

We conclude that in human infants below the age of about 6 months mutation is rare, but that when it occurs it can be accompanied by selection. Beyond 6 months of age, mutation is found with increasing frequency and the R/S ratios are sufficiently high in the CDR to indicate selection. Whilst mutation and selection show a clear maturation in infants, CDR3 length and D/J gene usage appear not to be correlated with maturity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs E. J. (Ted) Steele and Mike Brisco for helpful discussions, and Jacqui Aldis for help with recruiting vaccinees. This work was supported by a grant from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council.

References

- 1.Gathings WE, Kubagawa H, Cooper MD. A distinctive pattern of B cell immaturity in perinatal humans. Immunol Rev. 1981;57:107–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1981.tb00444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson CB. Immunologic basis for increased susceptibility of the neonate to infection. J Pediatr. 1986;108:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(86)80761-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holt PG. Postnatal maturation of immune competence during infancy and childhood. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 1995;6:59–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.1995.tb00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith RT, Eitzman DV, Catlin ME, Wirtz EO, Miller BE. The development of the immune response. Characterization of the response of the human infant and adult to immunization with salmonella vaccines. Pediatrics. 1964;68:163–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rijkers GT, Sanders LA, Zegers BJ. Anti-capsular polysaccharide antibody deficiency states. Immunodeficiency. 1993;5:1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Sant'Agnese PA. Simultaneous immunization of new-born infants against diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis. Am J Public Health. 1950;40:674–80. doi: 10.2105/ajph.40.6.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurikka S, Kayhty H, Saarinen L, Ronnberg PR, Eskola J, Makela PH. Immunologic priming by one dose of Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine in infancy. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:1268–72. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.5.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ridings J, Nicholson IC, Goldsworthy W, Haslam R, Roberton DM, Zola H. Somatic hypermutation of immunoglobulin genes in human neonates. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;108:366–74. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.3631264.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein U, Kuppers R, Rajewsky K. Variable region gene analysis of B cell subsets derived from a 4-year-old child: somatically mutated memory B cells accumulate in the peripheral blood already at young age. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1383–93. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.4.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van DijkHard I, Soderstrom I, Feld S, Holmberg D, Lundkvist I. Age-related impaired affinity maturation and differential D–JH gene usage in human VH6-expressing B lymphocytes from healthy individuals. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:1381–6. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berman JE, Mellis SJ, Pollock R, et al. Content and organization of the human Ig VH locus: definition of three new VH families and linkage to the Ig CH locus. EMBO J. 1988;7:727–38. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02869.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berman JE, Nickerson KG, Pollock RR, et al. VH gene usage in humans: biased usage of the VH6 gene in immature B lymphoid cells. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21:1311–4. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830210532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davidkova G, Pettersson S, Holmberg D, Lundkvist I. Selective usage of VH genes in adult human B lymphocyte repertoires. Scand J Immunol. 1997;45:62–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1997.d01-376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Logtenberg T, Young FM, Van Es JH, Gmelig Meyling FH, Alt FW. Autoantibodies encoded by the most JH-proximal human immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region gene. J Exp Med. 1989;170:1347–55. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.4.1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andris JS, Brodeur BR, Capra JD. Molecular characterization of human antibodies to bacterial antigens: utilization of the less frequently expressed VH2 and VH6 heavy chain variable region gene families. Mol Immunol. 1993;30:1601–16. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(93)90452-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Settmacher U, Jahn S, Siegel P, von Baehr R, Hansen A. An anti-lipid A antibody obtained from the human fetal repertoire is encoded by VH6-V lambda 1 genes. Mol Immunol. 1993;30:953–4. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(93)90021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brezinschek HP, Foster SJ, Brezinschek RI, Dorner T, DomiatiSaad R, Lipsky PE. Analysis of the human V-H gene repertoire—differential effects of selection and somatic hypermutation on human peripheral CD5(+)/IgM(+) and CD5(-)/IgM(+) B cells. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:2488–501. doi: 10.1172/JCI119433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meek K, Eversole T, Capra JD. Conservation of the most JH proximal Ig VH gene segment (VHVI) throughout primate evolution. J Immunol. 1991;146:2434–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Insel RA, Varade WS. Bias in somatic hypermutation of human VH genes. Int Immunol. 1994;6:1437–43. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.9.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wagner SD, Neuberger MS. Somatic hypermutation of immunoglobulin genes. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:441–57. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dorner T, Brezinschek HP, Brezinschek RI, Foster SJ, DomiatiSaad R, Lipsky PE. Analysis of the frequency and pattern of somatic mutations within nonproductively rearranged human variable heavy chain genes. J Immunol. 1997;158:2779–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jukes TH, King JL. Evolutionary nucleotide replacements of DNA. Nature. 1979;281:605–6. doi: 10.1038/281605a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaartinen M, Kulp S, Makela O. Characteristics of selection-free mutations and effects of subsequent selection. In: Steele EJ, editor. Somatic mutations in V-regions. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1991. pp. 105–14. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oprea M, Perelson AS. Somatic mutation leads to efficient affinity maturation when centrocytes recycle back to centroblasts. J Immunol. 1997;158:5155–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohlin M, Borrebaeck CA. Characteristics of human antibody repertoires following active immune responses in vivo. Mol Immunol. 1996;33:583–92. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(96)00018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mortari F, Wang JY, Schroeder HW. Human cord blood antibody repertoire. Mixed population of VH gene segments and CDR3 distribution in the expressed C alpha and C gamma repertoires. J Immunol. 1993;150:1348–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]