Abstract

Blood samples from 29 preterm (24–32 weeks of gestation) and 21 full-term (37–42 weeks of gestation) neonates were analysed for surface markers of lymphocyte subtypes and macrophages, and the effects of gestational age, neonatal infection, maternal pre-eclampsia, maternal betamethason therapy and mode of delivery were assessed with multiple regression analysis. Gestational age alone had few independent effects (increase in CD3+, CD8+CD45RA+, and CD11α+ cells, and decrease in CD14+, HLA-DR− cells) during the third trimester on the proportions of the immune cell subtypes studied. Neonatal infection and mother's pre-eclampsia had the broadest and very opposite kinds of effects on the profile of immune cells in the blood. Infection of the neonate increased the proportions of several ‘immature’ cells (CD11α−CD20+, CD40+CD19−, and CD14+HLA-DR−), whereas mother's pre-eclampsia decreased the proportions of naive cell types (CD4+CD8+, CD5+CD19+). In addition, neonatal infection increased the proportion of T cells (CD3+, CD3+CD25+, and CD4+/CD8+ ratio, and CD45RA+ cells), while maternal pre-eclampsia had a decreasing effect on the proportion of CD4+ cells, CD4+/CD8+ ratio, and proportions of CD11α+, CD14+ and CD14+HLA-DR+ cells. Maternal betamethason therapy increased the proportion of T cells (CD3+) and macrophages (CD14+, CD14+HLA-DR+), but decreased the proportion of natural killer (NK) cells. Caesarean section was associated with a decrease in the proportion of CD14+ cells. We conclude that the ‘normal range’ of proportions of different mononuclear cells is wide during the last trimester; further, the effect of gestational age on these proportions is more limited than the effects of other neonatal and even maternal factors.

Keywords: lymphocyte subpopulations, neonatal infection, prematurity, pre-eclampsia

INTRODUCTION

The development of the immune system is characterized by sequential events that begin early during fetal life [1,2]. Very little is known about the phenotypes of the immune cells in preterm newborns. Since at 18–22 weeks of gestation blood samples are sometimes drawn for perinatal diagnosis of severe inherited diseases, some data exist on lymphocyte subtypes [3,4]; the composition of the lymphocyte subtypes seems already at that time to be remarkably similar to that in full-term newborns [5–9]. However, it is quite different from adults, and further maturation is thought to take place upon multiple antigen contacts after birth. This is illustrated, for example, by antibody production, which is impaired in newborns [10,11] and reaches its full capacity later during childhood [12].

The aim of this study was to elucidate the changes in immune cell composition during the last trimester using several surface markers that reflect maturation and/or activation of the cells. However, because the reasons that underlie prematurity are often complex, it is difficult to differentiate between the changes due to immaturity itself and those that result from the cause of the prematurity, or from other perinatal factors. Multiple regression analysis is a statistical method that allows one to evaluate independent effects of multiple factors simultaneously. We utilized multiple regression analysis to distinguish between the effect of gestational age and the effects of neonatal infection, maternal pre-eclampsia, maternal betamethason therapy, and mode of delivery on the immune cell composition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Blood samples from 29 preterm and 21 full-term newborns were included in this study. The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Children's Hospital. The presence of maternal pre-eclampsia or neonatal infection was diagnosed by a senior doctor by evaluating case history (maternal symptoms, e.g. high blood pressure, proteinuria, oedema, fever, and laboratory findings), clinical status (respiratory and circulatory symptoms and irritability), and laboratory findings (leucocyte, thrombocyte, C-reactive protein (CRP) values, aerobic and anaerobic blood culture, and arterial blood gas analysis). Twenty-five of 29 mothers of the preterm newborns had received betamethason (12 mg, once or twice at 12-h intervals, of Celeston Chronodose; Schering-Plough, Heist-Op-Den-Berg, Belgium) treatment before delivery. After birth, blood samples (1.2 ml) from preterm babies were obtained from intra-arterial lines established for routine clinical tests. The average age of the newborns at the time of sample collection was 16.3 h (range 3–39 h). Ten of the preterm babies were born at 24–26, 11 at 27–29, and eight at 30–32 weeks of gestation; 20 of them were delivered by caesarean section. Nine of the preterm babies were born to mothers with severe pre-eclampsia, and 10 had a neonatal systemic infection; the diagnoses of the other 10 preterm babies included non-identical twins (2 pairs + 1 = 5), premature birth due to cervix insufficiency (n = 2), placenta ablation (n = 1), and prematurity of unknown cause (n = 2). From the 21 healthy full-term (37–42 weeks of gestational age) newborns, cord blood (CB) samples were obtained from umbilical cord vessels within minutes after either a vaginal delivery (6/21) or an elective caesarean section (15/21). The clamped cord was punctured with a sterile needle attached to a syringe without any suction (Venoject; Terumo Europe N.V., Leuven, Belgium). When the needle was in the umbilical vessel, a tube with negative pressure was attached to the syringe. Using this technique, the possibility of contamination of CB with maternal blood is minimal.

Sample preparation and flow cytometric analysis

Immediately after sample collection 50 μl of whole blood were incubated with FITC- and/or PE-conjugated mouse anti-human MoAbs for 30 min at room temperature (in the dark). Erythrocytes were lysed with fluorescence-activated cell sorter lysing solution (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cells were washed twice in a phosphate buffer (Orion Diagnostica, Espoo, Finland), fixed with 0.5% paraformaldehyde, and stored at 4°C until analysis. Lymphocytes were gated from an unstained sample and the accuracy of the gate was monitored by a pan leucocyte marker CD45 (FITC) combined with a myeloid marker CD14 (PE) (Immunotech, Marseille, France). For each sample 10 000 gated events were analysed with FACScan flow cytometry (Becton Dickinson) equipped with either LYSYS II or CellQuest software. The MoAbs used were specific for: CD3, CD4, CD11α, CD14, CD19, and CD21 (all FITC-labelled); CD4, CD5, CD8, CD25, CD16 and CD56, and HLA-DR (all PE-labelled); IgG1-FITC/IgG2-PE as a negative control (all purchased from Immunotech); and CD20, CD23 and CD40 (all PE-conjugated, purchased from Serotec, Oxford, UK).

Statistical analysis

The associations between the proportions of different cell types and gestational age, neonatal infection, maternal pre-eclampsia, maternal betamethason therapy, and mode of delivery were assessed with a forward stepping multiple regression analysis. Gestational age was treated as a continuous variable, whereas the other factors were coded as dichotomous (yes/no) variables. The reported P values are not adjusted for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

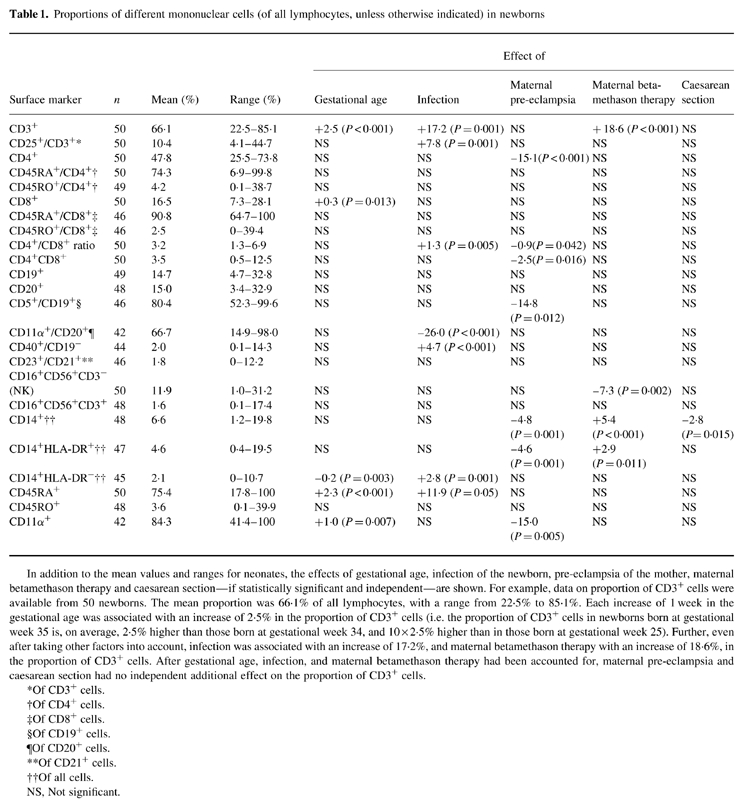

There were significant differences in the proportions of all different mononuclear cell types between individual newborns at the time of birth. In addition to gestational age, also infection, maternal pre-eclampsia, treatment of mother with betamethason, and mode of delivery were reflected in the cell composition of peripheral blood of the newborns. These differences are summarized in Table 1. There were no associations between time interval of betamethason treatment and blood sampling or gender, and cell type distribution. Since almost all babies (48/50) were of Caucasian descent, the effect of race could not be examined.

Table 1.

Proportions of different mononuclear cells (of all lymphocytes, unless otherwise indicated) in newborns

In addition to the mean values and ranges for neonates, the effects of gestational age, infection of the newborn, pre-eclampsia of the mother, maternal betamethason therapy and caesarean section—if statistically significant and independent—are shown. For example, data on proportion of CD3+ cells were available from 50 newborns. The mean proportion was 66.1% of all lymphocytes, with a range from 22.5% to 85.1%. Each increase of 1 week in the gestational age was associated with an increase of 2.5% in the proportion of CD3+ cells (i.e. the proportion of CD3+ cells in newborns born at gestational week 35 is, on average, 2.5% higher than those born at gestational week 34, and 10 × 2.5% higher than in those born at gestational week 25). Further, even after taking other factors into account, infection was associated with an increase of 17.2%, and maternal betamethason therapy with an increase of 18.6%, in the proportion of CD3+ cells. After gestational age, infection, and maternal betamethason therapy had been accounted for, maternal pre-eclampsia and caesarean section had no independent additional effect on the proportion of CD3+ cells.

*Of CD3+ cells.

†Of CD4+ cells.

‡Of CD8+ cells.

§Of CD19+ cells.

¶Of CD20+ cells.

**Of CD21+ cells.

††Of all cells.

NS, Not significant.

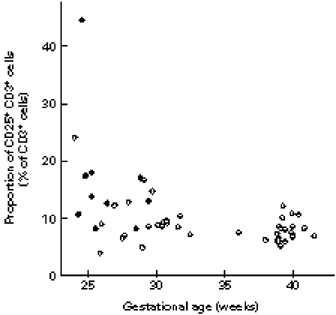

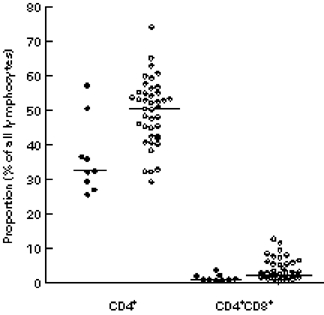

The proportion of CD3+ cells increased with gestational age, and in the presence of an infection; maternal betamethason therapy was the third factor associated with higher CD3+ cell proportion. Interestingly, the proportion of CD3+ cells that also expressed CD25 was significantly higher in newborns with than in those without infections (Fig. 1). The proportion of CD8+ cells increased with advancing gestational age. Maternal pre-eclampsia had a significant effect on T cell distribution: neonates born to mothers with pre-eclampsia had significantly less CD4+ cells and CD4+CD8+ double-positive cells than other neonates (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the CD4/CD8 ratio was decreased in these babies. In contrast, the CD4+/CD8+ ratio was increased in neonates with infection.

Fig. 1.

The association between the proportion of CD25+CD3+ cells, gestational age, and infection. •, Infected newborns; ○, uninfected newborns.

Fig. 2.

Proportions of CD4+ and CD4+CD8+ cells in neonates born to mothers with (•) or without (○) pre-eclampsia. Medians are denoted by horizontal lines.

In all newborns, > 50%—up to 99%—of CD19+ B cells were also CD5+. Maternal pre-eclampsia decreased the proportion of CD5+CD19+ cells by approx. 15%. A substantial proportion of all B cells were CD11α−: the lowest levels of CD11α+B cells were observed in those prematures who had an infection. Another interesting phenomenon was the occurrence of CD19−CD40+ cells: in three infected neonates, all very immature, born at 25 weeks of gestational age, 12–14% of all lymphocytes were CD40+ despite being CD19−.

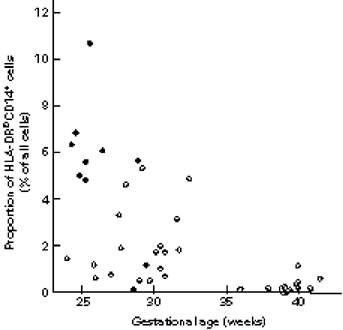

A significant proportion of the CD14+ cells of the newborns were HLA-DR−. There was an inverse correlation between gestational age and the proportion of HLA-DR−CD14+ cells; the very highest proportions of these cells were observed in those premature infants who also had a neonatal infection (Fig. 3). Maternal pre-eclampsia and treatment with betamethason had opposite effects on the proportion of HLA-DR+CD14+, as well as on the proportion of all CD14+ cells, pre-eclampsia diminishing and betamethason increasing these proportions. Further, caesarean section was associated with a decrease in the proportion of CD14+ cells.

Fig. 3.

The association between the proportion of HLA-DR−CD14+ cells and infection. •, Infected newborns; ○, uninfected newborns.

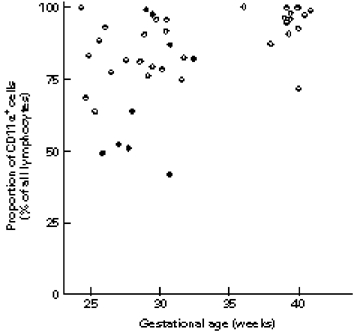

The proportion of CD45RA+ cells increased with gestational age, and was further accentuated by the presence of infection, while the proportion of CD45RO+ cells was not associated with either of those. Even the proportion of CD11α+ cells increased with advancing gestational age, but was decreased in the babies born to mothers with pre-eclampsia (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The association between the proportion of CD11α+ cells, gestational age, and maternal pre-eclampsia. •, Neonates born to mothers with pre-eclampsia; ○, neonates born to mothers without pre-eclampsia.

DISCUSSION

One of the most interesting findings of our study is the occurrence of ‘primitive’, or at least immature, cell types in the youngest premature newborns: CD11α− B cells, CD40+CD19− cells, and HLA-DR− monocytes/macrophages. The fact that all these cells were most prevalent in the babies with clinical infection raises an intriguing question: did these newborns contract the infection because of their extremely immature immune system, or were the cells released to peripheral blood merely in response to the stress imposed by the infection?

CD11α, expressed on all mature leucocytes, is an adhesive molecule that mediates migration of the cell into tissue and cell–cell contact [13,14]. Mature B cells require expression of CD11α also in order to develop into immunoglobulin-secreting cells: in vitro blocking of CD11α inhibits IgE, IgG, IgM and IgA production [15,16]. In preterm (or full-term) babies, high proportions of CD11α−B cells may therefore partially explain their impaired antibody production and susceptibility to infections. Alternatively, the decrease in proportion of CD11α+B cells in newborns with infection might perhaps reflect a situation where B cells are drawn away from the circulation via CD11α.

CD40 mediates immunoglobulin class switch from IgM to IgG [17–19]; inherited inability to express CD40L, a counterpart to CD40 on T cells, causes the hyper-IgM syndrome, where a person is practically unable to produce antibodies other than IgM [20], but the rest of the immune system seems to be unaffected. Knowing the limited specific function of CD40 on B cells, an increase in the proportion of CD40+ cells that are CD19− seems peculiar. CD40 has been reported to be involved with regulation of cell death [21]. However, it is also known that the CD40 molecule bears a striking homology to growth factor receptors, and may be functioning transiently on proliferating cells [22,23]; indeed, bone marrow myeloid cells have been described to express CD40 (CD34+CD19−CD40+ cells) [19]. We speculate that our observation of elevated proportions of CD40+CD19− cells in the three infected, extremely premature newborns is explained by the release of the primitive myeloid cells from the bone marrow into blood stream in response to the stress caused by infection.

HLA-DR molecules are involved in antigen processing and presentation, mediating antigen-specific T cell activation [24]. The proportion of HLA-DR− cells of all CD14+ cells has been reported to be smaller in adults (< 5%) than in full-term newborns (13%) [25]. In our material this proportion was, on average, 27%; the highest proportions were seen in the most premature babies. Further, infection of the newborn was another independent factor associated with an increase in the proportions of both all CD14+ cells and HLA-DR−CD14+ cells. Most likely the immune system is responding to infection by increasing the number of monocytes, but is unable to keep up with maturation (from HLA-DR-negative to positive) in a stress situation. Similarly, it seems that maturation or activation of increasing numbers of T cells (CD25+ cells of CD3+) upon infection is only slightly more efficiently established than that of CD14+ cells (Table 1).

The effect of maternal pre-eclampsia on the proportion of CD4+ cells and decreased CD4/CD8 ratio has been demonstrated before [5]. Baker et al. [5] postulated that the decreases in the proportion of these cells types and natural killer (NK) cells were merely reflecting intra-uterine malnutrition, a factor delaying or inhibiting maturation. However, our finding that the proportions of two ‘hallmarks’ of immature cell types (CD5+ B cells, and CD4+CD8+ double-positive T cells) decrease with maternal pre-eclampsia does not support this notion; rather, it is indicative of a more rapidly advancing maturation. Since even the proportions of CD14+HLA-DR+ and CD11α+ (in vitro secretion of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) has been associated with the proportion of CD18/CD11α+ cells [6]) are decreased in these babies, it seems that maternal pre-eclampsia has an inhibitory effect on the cell-mediated immunity. Treatment of mothers with a cortisone derivative, betamethason, prior to the delivery could theoretically cause such a suppression of the baby's immune system. This treatment, given in order to accelerate maturation of the lungs of the fetus, however, did not explain our findings, since betamethason had an opposite effect on the proportion of CD14+HLA-DR+ and NK cells, and a clear increasing effect on the proportion of T (CD3+) cells (Table 1)

Previous studies have shown that babies delivered vaginally have more NK cells than those born by caesarean section [26], a finding that could not be confirmed in the present study, where a decrease in the proportion of CD14+ cells was the only independent effect attributable to caesarean section.

The proportions of CD45RA, CD45RO, and CD11α/CD18+ cells increase during childhood [6], and CD45RA and CD45RO are believed to delineate ‘naive’ and ‘primed’ T cells [27]. In our study an age-dependent increase in the proportions of both all CD45RA and all CD11α+ cells could be demonstrated already during pregnancy. However, we cannot attribute these changes to any given cell type (i.e. CD4+ or CD8+ cells, or CD20+ cells, respectively). Neonatal infection increased the proportion of CD45RA+ cells by approx. 12%. This change could not be attributed to the T cell subtypes either. Furthermore, no changes could be seen in the proportions of CD45RO+ cells. Perhaps expression of CD45RO maturates later than that of CD45RA, since it has been reported that prematurity delays post-natal full expression of CD45RO [28].

In conclusion, we have demonstrated important baseline information on immune cell composition in both preterm and full-term newborns and that there are considerable differences in the proportions of any given cell subtype between different groups of newborns. Gestational age as such had a smaller independent effect than we had expected; in contrast, other neonatal and even maternal factors had more widespread effects that might have been erroneously attributed to gestational age had a multivariate analysis not been performed. Based on the observed relatively small effect of betamethason therapy on immune cell composition, therapy of mothers might not have to be deferred in fear of immunosuppressive effects in the neonates. Finally, the observed opposing effects of neonatal infection versus maternal pre-eclampsia on immune cell composition offer an interesting starting point for further studies.

Acknowledgments

A.K.-A. was supported by The Foundation for Paediatric Research.

References

- 1.Hayward AR. Development of lymphocyte responses and interactions in the human fetus and newborn. Immunol Rev. 1981;57:39–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1981.tb00441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burgio GR, Hanson LA, Ugazio A. Immunology of the neonate. Berlin: Springer; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lucivero G, D'Addario V, Tannoia N, Dell'Osso A, Gambatesa V, Lopalco PL, Cagnazzo G. Ontogeny of human lymphocytes. Two-color fluorescence analysis of circulating lymphocyte subsets in fetuses in the second trimester of pregnancy. Fetal Diagn and Ther. 1991;6:101–6. doi: 10.1159/000263632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peakman M, Buggins AG, Nicolaides KH, Layton DM, Vergani D. Analysis of lymphocyte phenotypes in cord blood from early gestation fetuses. Clin Exp Immunol. 1992;90:345–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb07953.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker DA, Hameed C, Tejani N, Thomas J, Dattwyler R. Lymphocyte subsets in the neonates of preeclamptic mothers. Am J Reprod Immunol Microbiol. 1987;14:107–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1987.tb00129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muller K, Zak M, Nielsen S, Pedersen FK, de Nully P, Bendtzen K. In vitro cytokine production and phenotype expression by blood mononuclear cells from umbilical cords, children and adults. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 1996;7:117–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.1996.tb00118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moretta A, Valtorta A, Chirico G, Chiara A, Bozzola M, De Amic M, Maccario R. Lymphocyte subpopulations in preterm infants: high percentage of cells expressing P55 chain of interleukin-2 receptor. Biol Neonate. 1991;59:213–8. doi: 10.1159/000243346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Motley D, Meyer MP, King RA, Naus GJ. Determination of lymphocyte immunophenotypic values for normal full-term cord blood. Am J Clin Pathol. 1996;105:38–43. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/105.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zola H, Fusco M, Macardle PJ, Flego L, Roberton D. Expression of cytokine receptors by human cord blood lymphocytes: comparison with adult blood lymphocytes. Pediatr Res. 1995;38:397–403. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199509000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruuskanen O, Pittard WB, Miller K, Pierce G, Sorensen RU, Polmar SH. Staphylococcus aureus Cowan I-induced immunoglobulin production in human cord blood lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1980;125:411–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watson W, Oen K, Ramdahin R, Harman C. Immunoglobulin and cytokine production by neonatal lymphocytes. Clin Exp Immunol. 1991;83:169–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1991.tb05609.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper MD, lymphocytes B. Current concepts.Normal development and function. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1452–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198712033172306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keizer GD, Borst J, Figdor CG, Spits H, Miedema F, Terhorst C, De VJE. Biochemical and functional characteristics of the human leukocyte membrane antigen family LFA-1, Mo-1 and p150,95. Eur J Immunol. 1985;15:1142–8. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830151114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marlin SD, Springer TA. Purified intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) is a ligand for lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1) Cell. 1987;51:813–9. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katada Y, Tanaka T, Ochi H, Aitani M, Yokota A, Kikutani H, Suemura M, Kishimoto T. B cell–B cell interaction through intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and lymphocyte functional antigen-1 regulates immunoglobulin E synthesis by B cells stimulated with interleukin-4 and anti-CD40 antibody. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:192–200. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tohma S, Ramberg JE, Lipsky PE. Expression and distribution of CD11a/CD18 and CD54 during human T cell–B cell interactions. J Leukoc Biol. 1992;52:97–103. doi: 10.1002/jlb.52.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clark EA, Ledbetter JA. Activation of human B cells mediated through two distinct cell surface differentiation antigens, Bp35 and Bp50. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:4494–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.12.4494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valle A, Zuber CE, Defrance T, De Djossou ORM, Banchereau J. Activation of human B lymphocytes through CD40 and interleukin 4. Eur J Immunol. 1989;19:1463–7. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830190818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saeland S, Duvert V, Caux C, et al. Distribution of surface-membrane molecules on bone marrow and cord blood CD34+ hematopoietic cells. Exp Hematol. 1992;20:24–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allen RC, Armitage RJ, Conley ME, et al. CD40 ligand gene defects responsible for X-linked hyper-IgM syndrome. Science. 1993;259:990–3. doi: 10.1126/science.7679801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hess S, Engelmann H. A novel function of CD40: induction of cell death in transformed cells. J Exp Med. 1996;183:159–67. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uckun FM. Regulation of human B-cell ontogeny. Blood. 1990;76:1908–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grimaldi JC, Torres R, Kozak CA, Chang R, Clark EA, Howard M, Cockayne DA. Genomic structure and chromosomal mapping of the murine CD40 gene. J Immunol. 1992;149:3921–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagy ZA, Baxevanis CN, Ishii N, Klein J. Ia antigens as restriction molecules in Ir-gene controlled T-cell proliferation. Immunol Rev. 1981;60:59–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1981.tb00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glover DM, Brownstein D, Burchett S, Larsen A, Wilson CB. Expression of HLA class II antigens and secretion of interleukin-1 by monocytes and macrophages from adults and neonates. Immunology. 1987;61:195–201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samelson R, Larkey DM, Amankwah KS, McConnachie P. Effect of labor on lymphocyte subsets in full-term neonates. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1992;28:71–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1992.tb00761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanders ME, Makgoba MW, Shaw S. Human naive and memory T cells: reinterpretation of helper-inducer and suppressor-inducer subsets. Immunol Today. 1988;9:195–9. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(88)91212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maccario R, Chirico G, Mingrat G, Arico M, Lanfranchi A, Montagna D, Moretta A, Rondini G. Expression of CD45RO antigen on the surface of resting and activated neonatal T lymphocyte subsets. Biol Neonate. 1993;64:346–53. doi: 10.1159/000244010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]