Abstract

MRL/lpr mice develop a systemic autoimmune disease characterized by autoantibodies and inflammatory lesions in various organs. The main cause of early mortality is glomerulonephritis. We previously found that MRL/lprγR−/− mice are protected from glomerulonephritis and have an increased life span compared with their MRL/lprγR+/+ littermates. We now carried out a histopathological study of a selection of organs of MRL/lprγR−/− mice. Mice were killed as soon as they showed clinical signs of disease. In the majority of animals skin lesions were the first apparent pathology. Mononuclear cell infiltrates were frequent in skin, lungs and kidneys, and they occurred also in liver, salivary glands and heart. In infiltrated areas there was an abnormal accumulation of bundles of collagen. In the lungs of MRL/lprγR−/− mice, and occasionally in other organs, small and middle-sized arteries and veins showed intimal proliferation, resulting in a narrowed lumen. Alveolitis was widespread. Mononuclear cell infiltrates and excessive production of collagen in the skin and several visceral organs, thickening of vascular intima and autoantibodies are characteristic features of human systemic sclerosis. Thus, MRL/lprγR−/− mice might represent a model for that disease.

Keywords: scleroderma, systemic sclerosis, autoimmunity, animal model

INTRODUCTION

The MRL/lpr murine strain is broadly used for investigating pathological mechanisms in systemic autoimmunity. MRL/lpr mice produce autoantibodies and are affected by chronic inflammatory diseases such as glomerulonephritis, vasculitis, arthritis and skin lesions [1,2]. Glomerulonephritis is by far the main cause of early mortality in MRL/lpr mice. MRL/lpr mice deficient for IFN-γ or for the IFN-γ receptor are protected from glomerulonephritis [3–5]. However, autoimmunity seems to persist to some extent in those mice, since their serum levels of autoantibodies, though lower than those of littermates with a functional IFN-γ signalling pathway, are still higher than in non-autoimmune controls [3,5]. In the present study we looked for histological evidence of autoimmune pathology in MRL/lprγR−/− mice. Mice were killed as they showed clinical signs of disease and selected tissues were examined.

The most striking histological findings in MRL/lprγR−/− mice were an accumulation of collagen in connective tissue of various organs and a vasculopathy characterized by intima thickening. The occurrence of these two alterations in an autoimmune background is reminiscent of systemic sclerosis in humans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and experimental design

The procedures for introduction of the IFNγR−/−mutation into the MRL/lpr background and for the determination of the genotype have been described previously [5]. For the present study we mated MRL/lprγR+/− mice of the F7 backcross generation. We followed 25 litters comprising 58 +/+ mice (27 males and 31 females) and 58 −/− mice (37 males and 21 females) up to the age of 10 months. Clinical observation, at a frequency of twice a week, started when the mice were 3 months of age. Special attention was paid to the aspect of the skin. Body weight and proteinuria were measured weekly. Proteinuria was evaluated with a dipstick (Albustix; Bayer Diagnostics, Basingstoke, UK). Mice were killed if one of the following observations was made: (i) proteinuria ≥ 3 mg/ml during 2 successive weeks, (ii) wound in diseased skin area, (iii) loss of body weight exceeding 15%, (iv) mouse showing a disturbed behaviour, like prostration. Blood was drawn from heart under deep anaesthesia using methoxyflurane and organs were sampled for histology.

Histology

Organ samples were collected from nine litters (22 MRL/lprγR+/+ and 27 MRL/lprγR−/−). Three females and three males of the C57/B6 strain, aged 7 months, were taken as controls. Tissues were fixed by immersion in 4% buffered paraformaldehyde. Fixed samples were embedded in paraffin and 3 μm thick sections were cut. All tissues were stained with the periodic acid Schiff (PAS) reagent. Other stains were used in order to confirm specific histopathological features: haematoxylin–eosin for identification of inflammatory cells, trichrome (azocarmin-anilin-orange G) for demonstration of collagen fibres, resorcin-fuchsin for staining of elastic lamina, phosphotungstic acid-haematoxilin for fibrin [6].

Phenotype of mononuclear cell infiltrates

This was carried out in six mice that had been killed because of necrotic skin lesions. Cryostat sections of unfixed shock-frozen kidneys were incubated with the following rat anti-mouse primary antibodies: anti-CD3 (clone KT3), anti-macrophage scavenger receptor (clone 2F8), anti-CD4 (clone YTS 191.1.2), anti-CD8 (clone 53-6.7). Cy3-labelled mouse anti-rat IgG was used as the second antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs, West Grove, PA). Cy3-labelled goat anti-mouse Ig(G + M) (Jackson ImmunoResearch) was used for detection of B cells. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (4,6-diamino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride; Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany). Total number of nuclei in an infiltrated area and numbers of cells labelled with a given antibody were evaluated on double fluorescence images (DAPI, blue; Cy3, red). At least 200 cells (nuclei) were evaluated for each mouse.

Assay of cryoglobulins

Blood samples taken at the time of sacrifice from 10 of each the MRL/lprγR+/+ and MRL/lprγR−/− populations were incubated for 1 h at 37°C and then centrifuged. One 100 μl of serum was incubated for 96 h at 4°C and then centrifuged for 15 min at 12 000 g. The pellets, containing cryoglobulins, were washed with 500 μl PBS at 4°C. After four wash steps followed by centrifugation, the pellets were resuspended in 100 μl PBS. The suspension was kept at 40°C for 2 h in order to dissolve the cryoglobulins. After one further centrifugation step the supernatants were collected for assay of IgG by ELISA. The standard curve, made of pure mouse IgG, ranged between 1 × 10−6 and 1 × 10−4 mg/ml mouse IgG. In preliminary assays the serum samples were diluted at several concentrations between 10−2 and 10−6; 10−2 and 10−5 were found convenient for MRL/lprγR−/− and MRL/lprγR+/+, respectively.

Adaptive immune responses

The humoral and cellular immune responses to rabbit immunoglobulins were evaluated in 3-month-old female mice. Six MRL/lprγR−/− and six MRL/lprγR+/+ mice were immunized with 200 μg of rabbit IgG in Freund's complete adjuvant (FCA). Ten days later 20 μl of 1 mg/ml rabbit IgG or 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA) were injected in the right and left footpad, respectively. The difference in thickness between the right and the left foot 24 h after injection was taken as a measure of the DTH reaction. One week later blood was sampled by heart puncture for measurement of anti-rabbit IgG antibody titres. All reagents for ELISA were from Sigma (St Louis, MO). Microtitre plates were coated with rabbit IgG at 1 μg/ml in PBS, washed, and blocked with BSA. Mouse sera were incubated overnight at dilutions ranging from 1:100 to 1:237 600 in 1:3 steps. Goat anti-mouse IgG1 or IgG2a coupled to alkaline phosphatase was used as second antibody and the disodium salt of p-nitrophenyl phosphate as the substrate. The absorbance at 405 nm was measured after 20 min of incubation at room temperature. The titre was the reciprocal value of the dilution yielding an absorption of 0.2 over background, calculated by extrapolation on a four-parameter plot.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data are expressed as the mean ± s.d. The anova software was used for comparison of experimental groups. The significance level was P < 0.05 in the Fischer's PLSD test.

RESULTS

Morbidity and mortality

The MRL/lprγR+/+ mice will not be described in detail. They were found previously to behave in a similar way to the original MRL/lpr population with respect to the incidence of glomerulonephritis, the production of autoantibodies, abnormally high numbers of CD4−CD8−T cells, and longevity [5]. In the present study 54 out of 58 had glomerulonephritis as revealed by proteinuria and histology and 49 showed vasculitis in the renal arteries.

MRL/lprγR−/− mice were killed mostly (45/58) because skin lesions had produced open wounds. Two males and no female survived the 10-month observation period without showing any symptom of disease. A further 11 mice died without showing skin necrosis. Two of these 11 were found dead and the other nine were killed because they showed proteinuria (one female, two males) or because they showed unspecific signs of illness like motoric inactivity or ruffled hairs (one female, seven males). Of the latter, two males had endocarditis and one showed a large intrathoracic lymph node, which might have caused impairment of cardiac or respiratory function. For the remaining five mice the cause of death was uncertain. However, all but one showed at least one of the histological abnormalities described below.

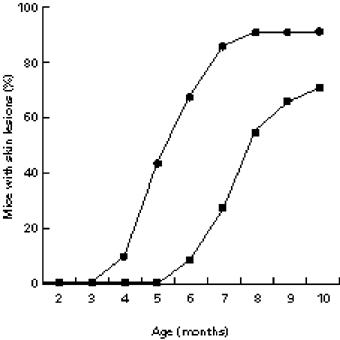

Skin disease appeared earlier in females than in males (Fig. 1). The earliest manifestations were erythema and hair rarefaction on the back and/or the ears. It then took between 2 and 4 weeks until wounds appeared. The latter may represent a consequence of the intense scratching which began as soon as erythema was visible. As the same histopathological alterations were found in males and in females in the six organs under study, no further distinction of gender will be made.

Fig. 1.

Incidence of skin disease in male (▪) and female (•) MRL/lprγ R−/− mice. The time of appearance of the first symptom was recorded.

Thrombosis

The mean age of animals subjected to histopathological study was 8.1 ± 1.4 months for the MRL/lprγR−/−, 4.7 ± 1.3 for the MRL/lprγR+/+ and 7 months for the C57BL/6. The incidence of the most characteristic lesions in organs of MRL/lprγR−/− mice is given in Table 1.

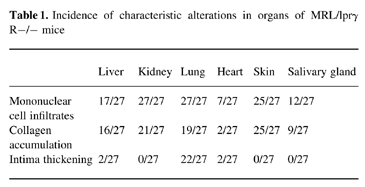

Table 1.

Incidence of characteristic alterations in organs of MRL/lprγ R−/− mice

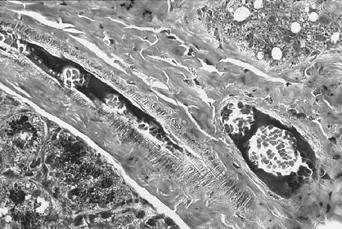

The only finding that was constant in all MRL/lprγR+/+ and MRL/lprγR−/− mice was the presence in small-sized arterial and venous vessels of thrombi which stained red with PAS. Although only a small fraction of the vessels displayed thrombi, these were found in all organs under study. We first suspected that they might consist of cryoglobulins, which are abundant in the plasma of MRL/lpr mice [1]. This is unlikely however, since in contrast to the MRL/lprγR+/+ mice, the sera of MRL/lprγR−/− mice contained low concentrations of cryoglobulins (548 ± 510 μg/ml versus 3 ± 3 μg/ml; mean ± s.d.; n = 10). The thrombi stained dark blue with phosphotungstic acid-haematoxylin, a stain that is reactive with fibrin [6] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Thrombi in an artery and in a vein, salivary gland. Staining: phosphotungstic acid-haematoxylin. (Mag. × 250.)

Vasculopathy

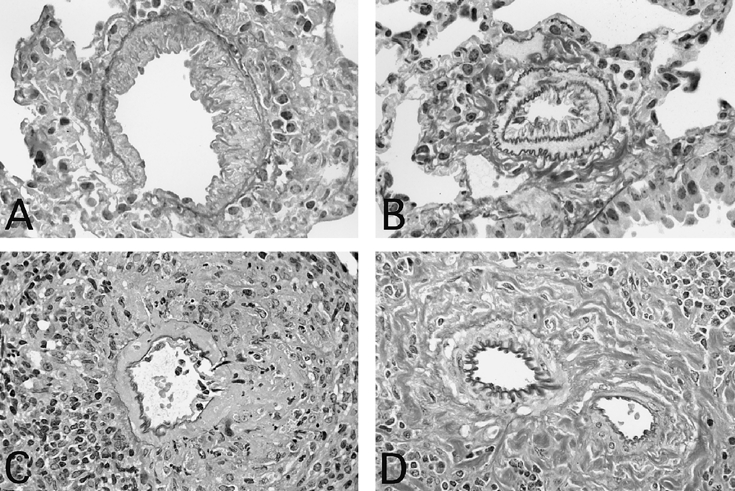

In the kidneys of MRL/lprγR+/+ animals signs of vascular inflammation, for instance necrosis in the media and disruption of the elastic membranes, were frequent in medium-sized arteries (Fig. 3). In that situation inflammatory cells were mostly macrophages and/or granulocytes. In contrast, in all MRL/lprγR−/− mice mononuclear cell cuffs around profiles of intrarenal arteries consisted mainly of small lymphocytes. The latter were mostly isolated from the vessel wall by large amounts of collagen (Figs 3 and 4). Necrosis was never observed and the external and internal elastic membranes remained intact. Thus, the perivascular infiltrates in MRL/lprγR−/− mice are not likely to reflect vasculitis.

Fig. 3.

Vasculopathy in lung (A,B) and in kidney (C,D). Intima thickening but intact elastic membranes in a small vein (A) and in a small artery (B) in a MRL/lprγR−/− mouse. An arcuate artery shows necrotizing vasculitis in a MRL/lprγR−/− mouse (C). In a MRL/lprγR−/− mouse (D) an arcuate artery appears intact in spite of a mononuclear cell cuff and of large amounts of collagen. Staining: resorcin-fuchsin. (Mag. × 430 (A,B); × 290 (C,D).)

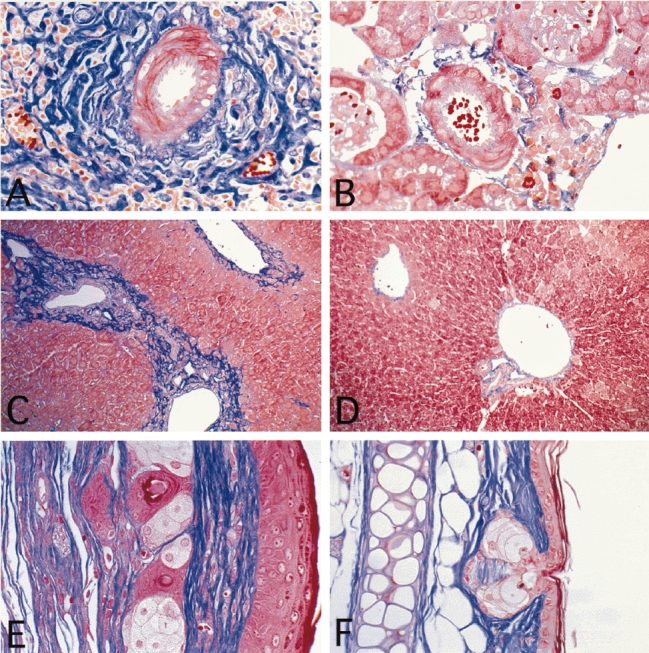

Fig. 4.

Accumulation of collagen in tissues of MRL/lprγR−/− mice (A,C,E) compared with C57/B6 mice (B,D,F). (A,B) Arcuate arteries in kidney. (C,D) Liver. (E,F) Ear. Staining: trichrome. (Mag. × 320 (A,B); × 150 (C,D,E,F).)

A complex pattern of vasculopathy was observed in the lungs of MRL/lprγR−/− mice. The most obvious alteration was a fibrocellular intima proliferation (Fig. 3). The blue colour with the trichrome stain (not shown) suggests that the fibrous material in the intima consists of collagen fibres. In the lungs frequent profiles of medium-sized veins showed intima thickening without any sign of infiltration of the media. In some profiles, however, the media underneath the thickened intima was focally disrupted by infiltrates but the elastic membrane remained intact (not shown). Intima thickening was also prominent in small pulmonal veins, in which the media was hardly detectable by light microscopy (Fig. 3). Small arteries and arterioles in the lung frequently showed narrowed, or occasionally completely obliterated lumina. In some profiles of small arteries it seemed that an amorphous extracellular material had accumulated beneath the endothelium. In other profiles there was a fibrocellular proliferation of the intima. Staining of the elastic membrane confirmed that proliferation affected the intima while the media remained normal (Fig. 3). In veins and arteries that kind of lesion was not accompanied by signs of necrotizing vasculitis, like nuclear fragments, fibrin deposits, predominance of macrophages or of granulocytes in the infiltrates. Intima thickening was only occasional in the other organs under study (Table 1).

Fibrosis

Compared with the non-autoimmune-prone strain C57/B6, bundles of collagen fibres in the connective tissues were more abundant and thicker in infiltrated areas of the skin, kidneys, liver, lungs and salivary glands of MRL/lprγR−/− mice (Fig. 4). In contrast, in MRL/lprγR+/+ mice the connective tissue, though frequently infiltrated by mononuclear cells, showed similar amounts of collagen to control mice (not shown). In the diseased skin areas, however, the amount of collagen was increased in both MRL/lprγR−/− and MRL/lprγR+/+ mice. Skin fibrosis has been already described in the MRL background [7].

Mononuclear cell infiltrates

In most MRL/lprγR−/− mice the heart hardly showed signs of disease besides thrombi in some small vessels (Table 1). Only occasional small mononuclear infiltrates were found in the surroundings of arteries. Severe myocarditis, however, was found in two mice and thickening of the intima of small arteries in two others.

The histology of diseased skin areas was similar in MRL/lprγR−/− mice to the MRL/lprγR+/+ counterparts. The main findings were acanthosis and proliferation of the connective tissue, both together resulting in a thickening of the skin (Fig. 4). There was no evidence of inflammation in the epidermis. Mononuclear cell infiltrates were found in the connective tissue, mostly in deep areas (Fig. 4). Specific association of infiltrates with structures such as vessels, hair follicles or glands was not evident.

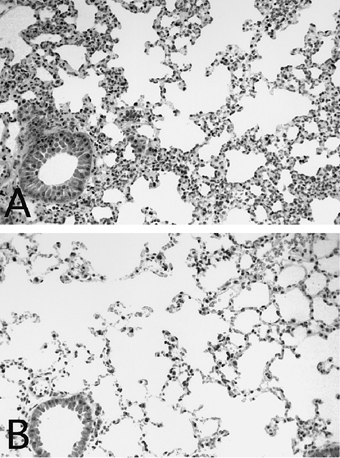

Mononuclear cell infiltrates were common around arteries, veins and/or bronchioles in the lungs of MRL/lprγR−/− and MRL/lprγR+/+ mice. The alveolar septa were infiltrated by mononuclear cells and few granulocytes and they were thickened (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Alveolitis in a MRL/lprγR−/− mouse (A) compared with a C57/B6 mouse (B). Staining: haematoxilin–eosin. (Mag. × 140.)

Perivascular mononuclear cell infiltrates were found in the livers (Fig. 4) and salivary glands (not shown) of MRL/lprγR+/+ as well as MRL/lprγR−/− mice. They were mostly restricted to the connective tissue surrounding the vessels and the secretory ducts.

The phenotype of cells infiltrating the connective tissue surrounding renal arcuate arteries was evaluated by immunofluorescence. Judging from expression of the macrophage scavenger receptor, 32.2 ± 7.2% of the cells in the perivascular infiltrates were macrophages. CD3+ T cells made up 56.2 ± 5.7% of the cells in the infiltrates. Most of them were T-helper cells, since CD4 was expressed by 41 ± 4.4% of the cells and CD8 by only 6 ± 3.7%. B cells, which amounted for 6.2 ± 3.5%, were mostly found in clusters at the periphery of the infiltrates.

Adaptive immune responses

The immune response to rabbit immunoglobulins in MRL/lprγ R−/−mice, compared with MRL/lprγR+/+ mice, was characterized by decreased titres of IgG2a (2184 ± 868 versus 10 459 ± 3356) and unchanged titres of IgG1 (107 555 ± 50 287 versus 84 668 ± 37 450), as well as an inhibition of DTH (0.08 ± 0.03 mm versus 0.30 ± 0.06 mm). The differences in IgG2a titres and in DTH were statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

Lack of expression of the IFN-γ receptor in MRL/lpr mice results in a striking protection against glomerulonephritis and in an increased longevity. However, the MRL/lprγR−/− mutants still produce autoantibodies. In the present study we looked for histological signs of inflammatory disease in six organs that are affected in the original MRL/lpr strain [1,2]. The most typical lesions in the MRL/lpr strain, namely glomerulonephritis and vasculitis, showed a low incidence in the MRL/lprγR−/− mice. In contrast, the latter displayed alterations that have not been described in the original MRL/lpr strain, namely exaggerated amounts of collagen in connective tissue in inner organs and a proliferative vasculopathy. Thus, MRL/lprγR−/−mice present a pattern of organ lesions that is new among murine models of systemic autoimmunity.

Production of autoantibodies, collagen accumulation accompanying mononuclear cell infiltrates in various organs and a vasculopathy characterized by intimal proliferation constitute three major criteria for the human disease systemic sclerosis. Interstitial lung disease is also a frequent finding in patients [8,9]. Thus, MRL/lprγR−/− mice might represent an interesting animal model for that disease.

Two findings, namely intima thickening and thrombi in the microvasculature, point to a possible impairment of vascular endothelial cell function in the MRL/lpr mouse. Thrombosis has been described before in that strain [10,11]. Intima proliferation and thrombotic tendency in patients with systemic sclerosis may be linked to altered properties of the endothelium [12,13]. Whether the endothelium in systemic sclerosis is a primary target of immune effectors or whether its function is altered secondarily to haemodynamic changes or to an abnormal function of platelets remains to be elucidated [12].

While the IFN-γR−/− mutation protected MRL/lpr mice from glomerulonephritis and necrotizing vasculitis, it seems to promote two alterations, namely a proliferative vasculopathy in the lung and fibrosis in some inner organs. This does not necessarily mean that IFN-γ is protective against those two diseases. It is also possible that the increased longevity of MRL/lprγR−/−mice compared with the MRL/lprγR+/+ counterparts allows enough time for the development of additional tissue alterations. As far as fibrosis is concerned, a direct influence of the MRL/lprγR−/− mutation seems possible, since the anti-fibrotic action of IFN-γ has been well documented [14–17]. Whatever the role of the lack of IFN-γ signalling in the development of histological alterations in MRL/lprγR−/− mice, this lack by itself adds an aspect to the analogy between that murine population and systemic sclerosis patients. Indeed, production of IFN-γ by T cells seems abnormally low in the latter [14,18,19]. Evolution of the skin disease in systemic scle-rosis can be slowed down by local treatment with IFN-γ [20,21].

The expected effects of an impaired IFN-γ signalling on adaptive immune response are decreases of cellular immunity and of IgG2 and IgG3 antibody production [22]. Indeed, in the present study the immune response to rabbit IgG was characterized by a lower DTH response and reduced IgG2a antibodies in comparison with MRL/lprγR+/+ mice. Thus, any DTH-type lesions should be delayed or blunted in the IFNγR−/− mutants. Inversely, accumulation of collagen and intima thickening are not likely to be initiated by a DTH response, since they were evident only in the MRL/lprγR−/− mice. Thus, the functional significance of the presence of CD4+ T cells and of macrophages at the sites of lesions remains unclear. Likewise, the therapeutic effect of IFN-γ on skin lesions in patients suggest that these lesions are not elicited by a DTH-like mechanism.

Cryoglobulins reach very high concentrations in the plasma of MRL/lpr mice [1,23]. They might play a role in the pathogenesis of glomerulonephritis and vasculitis [23]. However, even though cryoglobulins induce vasculitis in skin microvasculature [23], they are not required for skin lesions in MRL/lpr mice. Indeed, skin lesions were frequent in MRL/lprγR−/− mice in spite of the low levels of cryoglobulins.

Three models of spontaneous systemic sclerosis have been described so far. The L200 chickens [24,25] display a pathology close to the human disease. In the tight-skin mouse, in contrast to humans affected by systemic sclerosis, there is no evidence of autoimmune disease, subcutaneous connective tissue hyperplasia is not associated with leucocytic infiltration, and inner organs are not affected [25,26]. Also in the tight-skin 2 mouse, fibrosis has been reported only in the skin [25,27]. In the latter strain the dermis is infiltrated by mononuclear cells, but it is not known whether the mice present autoimmunity. Vasculopathy has not been reported in those two murine models. The large amount of data available concerning histopathology, immunological abnormalities and gene-tics of MRL/lpr mice constitutes a further advantage in comparison with the models of systemic sclerosis investigated so far.

Acknowledgments

This study has been supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation, grant 31-39543.93.

References

- 1.Andrews BS, Eisenberg RA, Theofilopoulos AN, et al. Spontaneous murine lupus-like syndromes. Clinical and immunopathological manifestations in several strains. J Exp Med. 1978;148:1198–215. doi: 10.1084/jem.148.5.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Theofilopoulos AN. Murine models of lupus. In: Lahita RG, editor. Systemic lupus erythematosus. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1992. pp. 121–94. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peng SL, Moshlehi D, Craft J. Roles of interferon-gamma and interleukin-4 in murine lupus. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:1936–46. doi: 10.1172/JCI119361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balomenos D, Rumold R, Theophilopoulos AN. Interferon-gamma is required for lupus-like disease and lymphadenopathy. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:364–71. doi: 10.1172/JCI750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haas C, Ryffel B, Le Hir M. IFN-gamma is essential for the development of autoimmune glomerulonephritis in MRL/Ipr mice. J Immunol. 1997;158:5484–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pearse AGE. Histochemistry. 3. Edinburg: Churchill Livingstone; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furukawa F, Tanaka H, Sekita K, Nakamura T, Horiguchi Y, Hamashima Y. Dermatopathological studies on skin lesions of MRL mice. Arch Dermatol Res. 1984;276:186–94. doi: 10.1007/BF00414018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harrison NK, Myers AR, Corrin B, et al. Structural features of interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:706–13. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.3_Pt_1.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silver RM. Interstitial lung disease of systemic sclerosis. Intern Rev Immunol. 1995;12:281–91. doi: 10.3109/08830189509056718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berden JHM, LeMing H, McConahey PJ, Dixon FJ. Analysis of vascular lesions in murine SLE I. Association with serologic abnormalities. J Immunol. 1983;130:1699–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamamoto K, Loskutoff DJ. The kidneys of mice with autoimmune disease acquire a hypofibrinolytic/hypercoagulant state that correlates with the development of glomerulonephritis and tissue microthrombosis. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:725–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kahaleh MB. The vascular endothelium in scleroderma. Intern Rev Immunol. 1995;12:227–45. doi: 10.3109/08830189509056715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pearson JD. The endothelium: its role in scleroderma. Ann Rheum Dis. 1991;50:866–71. doi: 10.1136/ard.50.suppl_4.866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Postlethwaite AE. Role of T cells and cytokines in effecting fibrosis. Intern Rev Immunol. 1995;12:247–58. doi: 10.3109/08830189509056716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tiggelman AM, Boers W, Linthorst C, Sala M, Chalumeau RA. Collagen synthesis by human liver (myo) fibroblasts in culture: evidence for a regulatory role of IL-1 beta, IL-4, TGF beta and IFN gamma. J Hepathol. 1995;23:307–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Granstein RD, Flotte TJ, Amento EP. Interferons and collagen production. J Invest Dermatol. 1990;95(Suppl. 6):75S–80S. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12874789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Serpier H, Gillery P, Salmon-Ehr V, et al. Antagonistic effects of interferon-gamma and interleukin-4 on fibroblast cultures. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;109:158–62. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12319207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prior C, Haslam PL. In vivo levels and in vitro production of interferon-gamma in fibrosing interstitial lung disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 1992;88:280–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb03074.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mavilia C, Scaletti C, Romagnani P, et al. Type 2 helper T-cell predominance and high CD30 expression in systemic sclerosis. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:1751–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunzelmann N, Anders S, Fierlbeck G, et al. Systemic scleroderma. Multicenter trial of 1 year of treatment with recombinant interferon gamma. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:609–13. doi: 10.1001/archderm.133.5.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vlachoyannopoulos PG, Tsifetaki N, Dimitriou I, Galaris D, apiris SA, Moutsopoulos HM. Safety and efficacy of recombinant gamma interferon in the treatment of systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Diseases. 1996;55:761–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.55.10.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finkelman FD, Holmes J, Katona IM, et al. Lymphokine control of in vivo immunoglobulin isotype selection. Annu Rev Immunol. 1990;8:303–33. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.001511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Izui S, Berney T, Shibata T, Fulpius T. IgG3 cryoglobulins in autoimmune MRL-lpr/lpr mice: immunopathogenesis, therapeutic approaches and relevance to similar human diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 1993;52:S48–S54. doi: 10.1136/ard.52.suppl_1.s48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gershwin ME, Abplanalp H, Castles JJ, et al. Characterization of a spontaneous disease of white leghorn chickens resembling progressive systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) J Exp Med. 1981;153:1640–59. doi: 10.1084/jem.153.6.1640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Water J, Jimenez SA, Gershwin ME. Animal models of scleroderma: contrasts and comparisons. Intern Rev Immunol. 1995;12:201–16. doi: 10.3109/08830189509056713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Green MC, Sweet HO, Bunker LE. Tight-skin, a new mutation of the mouse causing excessive growth of connective tissue and skeleton. Am J Pathol. 1976;82:493–512. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christner PJ, Peters J, Hawkins D, Siracusa LD, Jimenez SA. The tight skin 2 mouse. An animal model of scleroderma displaying cutaneous fibrosis and mononuclear cell infiltration. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1791–8. doi: 10.1002/art.1780381212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]