Abstract

To examine the potential pathogenic role of IL-10 in HIV infection, we measured serum IL-10 levels in 51 HIV-infected patients and 23 healthy controls both on cross-sectional and longitudinal testing. All clinical groups (Centers for Disease Control (CDC) categories) of HIV-infected patients had significantly higher circulating IL-10 levels than controls, with the highest levels among the AIDS patients, particularly in patients with ongoing Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) infection. Among 32 HIV-infected patients followed with longitudinal testing (median observation time 39 months), patients with disease progression had increasing IL-10 levels in serum, in contrast to non-progressing patients where levels were stable. While both IL-10 and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) increased in patients with disease progression, the IL-10/TNF-α ratio decreased in these patients, suggesting imbalance between these two cytokines. Finally, we found that highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) induced a significant, gradual decrease in IL-10 levels but without normalization. These findings suggest a pathogenic role for IL-10 in HIV infection, and may suggest a possible role for immunomodulating therapy which down-regulates IL-10 activity in addition to concomitant potent anti-retroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients.

Keywords: HIV infection, IL-10, tumour necrosis factor-alpha, Mycobacterium avium complex, anti-retroviral therapy

INTRODUCTION

IL-10, initially described as a T helper 2 (Th2) cell product, has more recently been found to be produced also by B cells, monocytes, natural killer (NK) cells and various tumour cell lines [1–5]. Although anti-inflammatory effects of IL-10 with inhibition of inflammatory cytokines have received much attention, stimulatory effects on immune system cells (e.g. B cells) have also been described for this cytokine [4–7].

Th1 cells are the principal effectors of cell-mediated immunity against intracellular microbes, whereas Th2 cells are important in providing help to B cells in antibody production [8–10], and an imbalance between Th1 and Th2 responses has been suggested to be involved in the pathogenesis of HIV infection [10–12]. However, while several reports suggest a shift in cytokine pattern from Th1 to Th2 cytokine profile along with disease progression in HIV-infected patients with an increase in IL-10 levels, others have not confirmed this [12–20]. Nevertheless, several studies have shown that IL-10 production is induced in vivo and in vitro during HIV infection and that neutralization of endogenous IL-10 may improve defective antigen-specific T cell function in HIV-infected patients [2,12–14,21, 22]. On the other hand, IL-10 may inhibit T cell apoptosis [23], a potential beneficial effect in these patients. Moreover, while IL-10 has been found to inhibit HIV replication in acutely infected macrophages at concentrations that block endogenous cytokine secretion [21, 24], lower IL-10 concentrations appear to enhance HIV replication [25]. Thus, the present data are conflicting and the contribution of IL-10 to the immunopathogenesis of HIV infection remains unclear.

To examine further the possible role of IL-10 in HIV infection, in the present study we measured IL-10 levels in serum in different clinical and immunological stages of HIV infection. Furthermore, in contrast to previous studies, IL-10 levels were also measured during longitudinal testing and the effect of highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) on circulating IL-10 levels was also examined.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

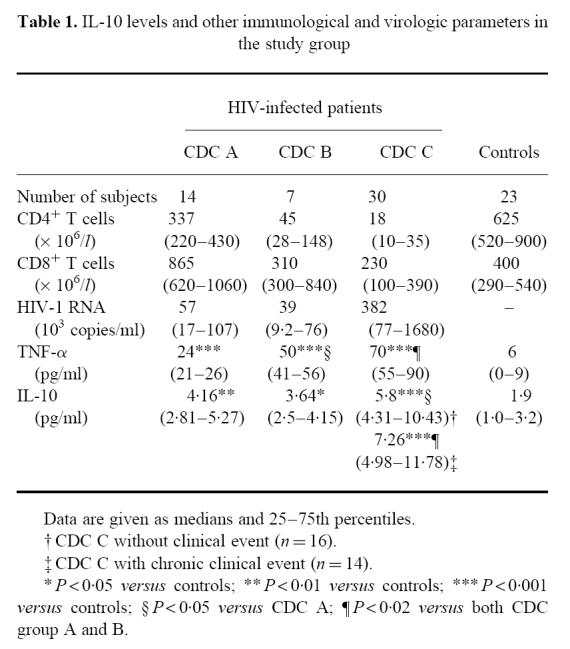

Fifty-one HIV-infected patients (median age 38 years, range 22–59 years; 40 males and 11 females) were included in the study. All patients were included in the cross-sectional study, and 32 of the patients were also followed during longitudinal testing (see below). In the cross-sectional study only the last serum sample from each patient was included. The patients were classified clinically according to the revised criteria from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [26], and some clinical, immunological and virologic characteristics of the study group at the time of the cross-sectional testing are given in Table 1. In the cross-sectional and longitudinal study only blood samples taken in periods without any acute or exacerbation of chronic infection were included. When examining IL-10 levels in relation to clinical events blood samples from the same study populations taken during clinical events were selected. Twenty-three healthy HIV− blood donors (median age 38 years, range 22–55 years; 17 males and six females) were used as controls.

Table 1.

IL-10 levels and other immunological and virologic parameters in the study group

|

Blood sampling protocol

Blood was drawn into pyrogen-free tubes without any additives. Tubes were immediately immersed in melting ice, centrifuged (600 g for 10 min) after clotting (within 1 h) and serum was stored at −80°C until analysis. Samples were frozen and thawed only once.

Quantification of IL-10 and tumour necrosis factor-alpha by enzyme immunoassay

Serum levels of IL-10 were quantified by a high-sensitivity enzyme immunoassay (EIA; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Serum concentrations of immunoreactive tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) was quantified by EIA (Medgenix, Fleurus, Belgium) as previously described [27]. In our laboratory the limit of detection was 0.5 pg/ml (IL-10) and 3 pg/ml (TNF-α). The intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were < 10% for both EIAs. All samples from a given patient were analysed in the same microtitre plate to minimize run-to-run variability.

Quantification of lymphocyte subsets in peripheral blood

CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocyte counts were determined by immunomagnetic quantification [28].

Quantification of HIV RNA copy numbers in plasma

HIV RNA levels were measured in EDTA plasma by quantitative reverse polymerase chain reaction (PCR; Amplicor Monitor; Roche Diagnostic Systems, Branchburg, NY). The limit of detection was 200 copies/ml.

Statistical analysis

When comparing two groups of individuals we used two-tailed Mann–Whitney U-test. When comparing more than two groups, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used. If a significant difference was found, the Mann–Whitney U-test was used to determine differences between each pair of groups. Coefficient of correlation was calculated by the Spearman rank test. Responses within the same individuals were compared by (two-tailed) Wilcoxon signed rank test for paired data. Differences in Kaplan–Meier estimates were tested by the log rank test. Data are given as medians and 25–75th percentiles if not otherwise stated. P values were two-sided and considered significant when < 0.05.

RESULTS

IL-10 levels in cross-sectional testing

When examining serum IL-10 levels in 51 HIV-infected patients and 23 healthy controls, we found that all clinical groups of HIV-infected patients had significantly higher IL-10 levels than controls, with the highest levels in CDC group C (Table 1). In the CDC group C, 14 patients had chronic events in a stable phase (cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis, n = 6, Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) infection, n = 8). However, also when excluding these AIDS patients with chronic events, patients in the CDC group C still had higher IL-10 levels than patients in both CDC groups A and B (Table 1). Furthermore IL-10 levels were significantly negatively correlated with CD4+ (r = −0.43, P < 0.003) and CD8+ (r = −0.39, P < 0.01) T cell counts in peripheral blood and significantly positively correlated with HIV-RNA copy numbers in plasma (r = 0.50, P < 0.005).

IL-10 levels in relation to clinical events

We next analysed serum levels of IL-10 in 19 patients having an ongoing AIDS-related clinical event in an acute phase based on established diagnostic criteria [26]: eight patients had disseminated infection with MAC, six patients had symptomatic CMV infection and five patients had Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP). IL-10 levels in these patients were compared with levels in 16 AIDS patients, but without any ongoing clinical event. There were no significant differences in CD4+ T cell counts between these subgroups of patients (data not shown). However, we found that patients with MAC infection (12.1 (9.4–19.3) pg/ml) had significantly higher IL-10 levels than both patients in CDC group C without clinical event (5.8 (4.3–10.4) pg/ml) as well as those with CMV infection (6.13 (5.0–7.0) pg/ml) or PCP (7.7 (7.0–8.0) pg/ml) (P < 0.05). In contrast, levels of IL-10 in patients with PCP or CMV infection were not significantly different from AIDS patients without any ongoing clinical event.

IL-10 levels during longitudinal testing

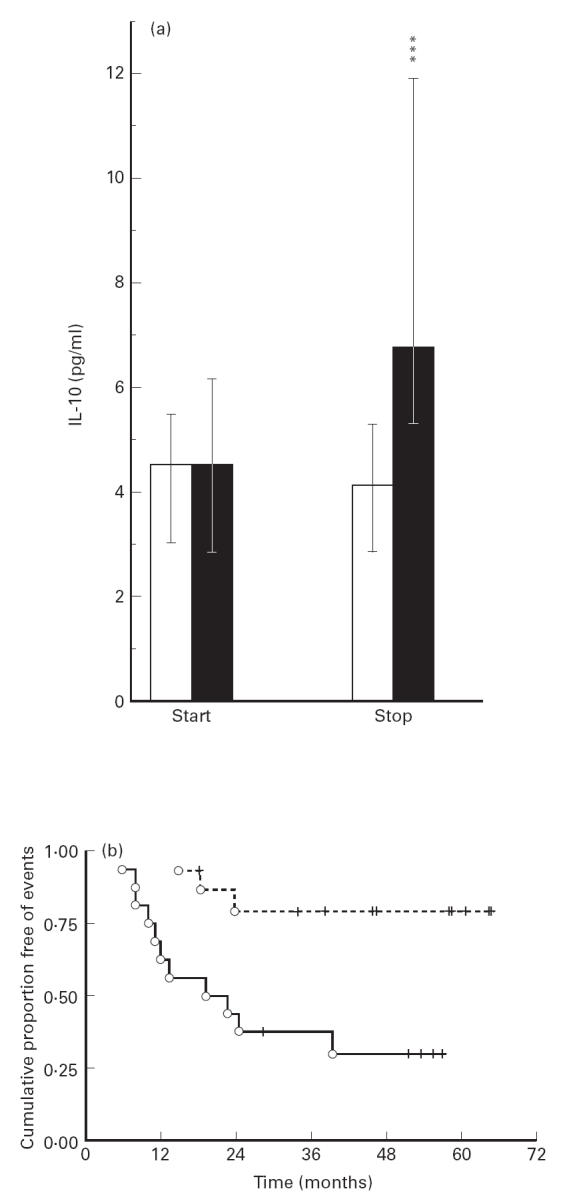

To examine whether disease progression is associated with IL-10 levels also during longitudinal testing, serum samples from 32 of the patients in which follow-up data for a period of at least 15 months were available were analysed for IL-10 concentrations (median observation time 39 months (range 17–65 months), median numbers of blood samples five (range three to six)). At baseline 22 patients were classified in CDC group A, eight in CDC group B and two patients in CDC group C. During the study period 19 patients received PCP prophylaxis and 19 patients received single nucleoside analogue therapy, but none received nucleoside analogues in combination or HAART. Patients were defined as clinical progressors if they fulfilled one of the following criteria during the study: (i) death from HIV complication; (ii) clinical progression as reflected in altered CDC classification; (iii) a new AIDS-defining event (for patients in CDC group C at baseline). Only one patient (progressor) developed MAC infection.

At baseline there was no significant difference in IL-10 levels between progressors and non-progressors (Fig. 1). However, while non-progressors had stable IL-10 levels throughout the study period, there was an increase in IL-10 concentrations among progressors, resulting in a significant difference in IL-10 levels between these two groups of patients at the end of the study (Fig. 1). Exclusion of the MAC-infected patient from the analysis did not change this pattern. Furthermore, when these 32 patients were divided into two equal groups according to their IL-10 levels at the end of the study ( > or < median IL-10 levels in all patients (5.26 pg/ml)), the clinical progression was significantly lower in patients with IL-10 levels < median (Fig. 1). Similar patterns were found when the patients were divided into two equal groups according to their actual or time-adjusted rate of change in circulating IL-10 (i.e. slope), in that IL-10 levels > median values were associated with more rapid progression in Kaplan–Meier estimates (P < 0.05).

Fig 1.

Serum levels of IL-10 during longitudinal testing. (a) IL-10 levels at the start (start) and the end (stop) of the study in two defined clinical groups of HIV-infected patients classified as progressors (▪, n = 14) and non-progressors (□, n = 18). Patients were classified as progressors if they fulfilled one of the following criteria during the study period: (i) death from HIV complication; (ii) clinical progression as reflected in altered CDC classification; (iii) a new AIDS-defining event (for patients in CDC group C at baseline). Data are given as medians, 25–75th percentiles. ***P < 0.001 versus non-progressors. (b) Kaplan–Meier plots showing differences in event-free periods between patients having circulating IL-10 above (solid lines) and below (broken lines) median IL-10 levels for all patients (5.25 pg/ml) at the end of the study. Vertical lines indicate censored cases (P = 0.005).

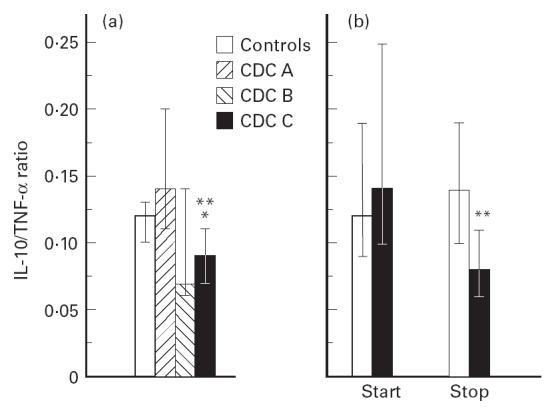

The balance between IL-10 and TNF-α during HIV infection

While IL-10 is a potent down-regulator of TNF-α production, TNF-α is in itself a stimulus for IL-10 release from various cells [29]. The balance between these two cytokines has been suggested to be of importance in the pathogenesis of HIV infection [30] and we therefore analysed serum levels of TNF-α in 38 HIV-infected patients, including 32 who participated in the longitudinal study, and in these 32 patients TNF-α levels were analysed at the start and at the end of the study period. As previously reported [27], HIV-infected patients had significantly elevated TNF-α levels (Table 1). However, while the highest concentrations of both IL-10 and TNF-α were found in the CDC group C, these patients also had significantly lower IL-10/TNF-α ratios comparing both controls and patients in CDC group A (Fig. 2a). Only one patient with MAC infection was included in the analysis. The exclusion of this patient from the analysis did not change the pattern regarding IL-10/TNF-α. Furthermore, while both increasing IL-10 (see above) and TNF-α (data not shown) levels were associated with disease progression in longitudinal testing, a decrease in IL-10/TNF-α ratio was also associated with progression of HIV-related disease. While there was no significant difference in IL-10/TNF-α ratio at baseline, progressors had a significantly lower ratio at the end of the study period comparing non-progressors (Fig. 2b). Furthermore, the two non-progressors with a marked increase in IL-10 levels (> 4 pg/ml) both had a fall in TNF-α, resulting in high IL-10/TNF-α ratios. Also, all the three progressors with a fall in IL-10 levels during the study period had a marked increase in TNF-α levels (> 40 pg/ml), resulting in low IL-10/TNF-α ratios. Thus, our data suggest that progression of HIV infection is associated with a more marked increase in TNF-α compared with the increase in IL-10 levels.

Fig 2.

The balance between IL-10 and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) in HIV infection. (a) IL-10/TNF-α ratio in three clinical groups of HIV-infected patients and 20 healthy blood donors. CDC A, asymptomatic HIV-infected patients (n = 14); CDC B, symptomatic non-AIDS HIV-infected patients (n = 6); CDC C, AIDS patients (n = 18). *P < 0.01 versus controls; **P < 0.001 versus CDC A. (b) IL-10/TNF-α ratio during longitudinal testing at the start (start) and the end (stop) of the study in two defined clinical groups of HIV-infected patients classified as progressors (▪, n = 14) and non-progressors (□, n = 18). For definition of progressors, see legend to Fig. 1. Data are given as medians and 25–75th percentiles. **P < 0.01 versus non-progressors.

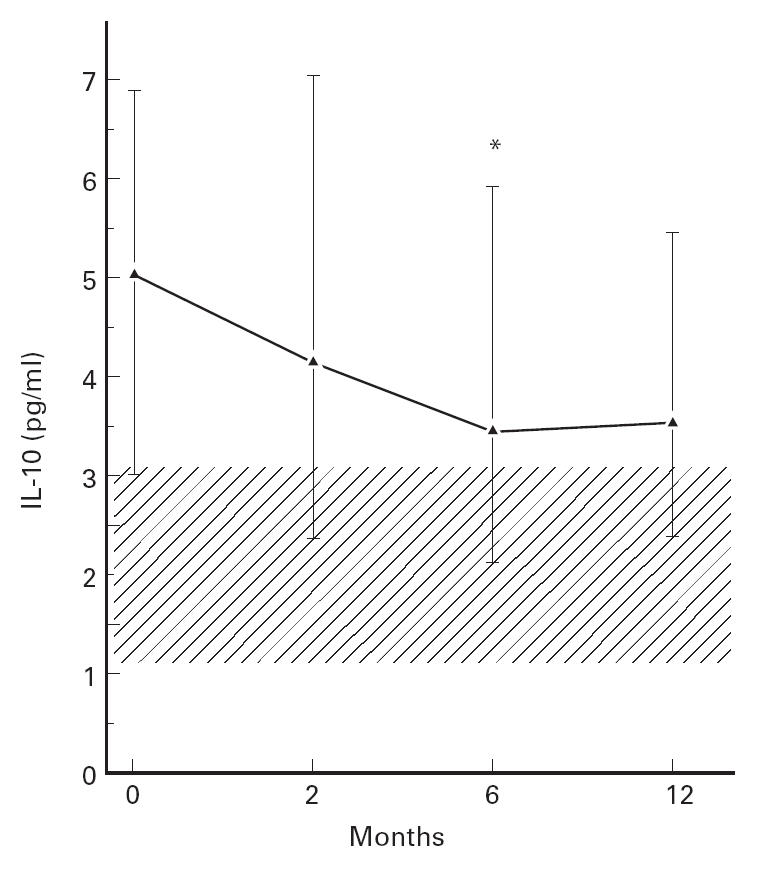

IL-10 levels during HAART

To elucidate further the role of IL-10 in HIV infection we next examined whether HAART had an effect on IL-10 levels in HIV-infected patients. We studied 16 patients treated with two nucleoside analogues (lamuvidine (150 mg bid) and zidovudine (250 mg bid), n = 13, or stavudine (40 mg bid) and lamuvidine (150 mg bid), n = 3) in combination with one HIV protease inhibitor agent (ritonavir (600 mg bid), n = 2, indinavir (800 mg tid), n = 10, saquinavir (600 mg tid) n = 4). IL-10 levels were analysed at baseline and 2, 6 and 12 months (n = 12), after initiating HAART. During therapy there was a significant increase in CD4+ (maximum increase 116 (87–142) × 106/l, P < 0.001) and CD8+ (322 (90–446) × 106/l, P < 0.05) T cell counts and a marked decrease in HIV RNA copy numbers in plasma (maximum decrease 2.49 (2.08–3.42) log10 copies/ml, P < 0.002). HAART also had an effect on IL-10 levels, resulting in decreased serum levels during the study period (Fig. 3). We have recently demonstrated a rapid fall in TNF-α (within 4 weeks) after initiated HAART, but without normalization at TNF-α levels [31]. However, in contrast to the rapid fall in plasma TNF-α and viral load and the rapid rise in CD4+ T cell counts, the decline in IL-10 levels was more delayed, reaching significantly lower levels than baseline only after 6 months of therapy, but with no normalization compared with control levels (Fig. 3). When comparing IL-10 levels with HIV-RNA copies in the whole HAART group, a highly significant positive correlation was found at both 6 (r = 0.63, P = 0.009) and 12 months (r = 0.76, P < 0.005) of treatment. Furthermore, after 6 months of therapy six patients still had detectable plasma viral RNA in plasma (> 200 copies/ml) and these patients had significantly higher IL-10 levels at 6 months compared with other patients (data not shown). Finally, one patient developed MAC infection during HAART and another 2 months after the last blood sample, and these two were the only patients with a marked rise in IL-10 levels during HAART.

Fig 3.

The effect of highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) on IL-10 levels in serum in 16 HIV-infected patients. The hatched area represents 25–75th percentile in healthy controls. Data are given as medians and 25–75th percentiles. *P < 0.05 versus baseline.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have reported discrepant results concerning IL-10 levels during HIV infection [12–20]. The present study demonstrates that HIV-infected patients have significantly higher circulating IL-10 levels than healthy controls, with the highest levels in patients with the most advanced clinical and immunological disease and high virus load. This was found regardless of concurrent illness, including MAC infection. We were also able to demonstrate that increasing IL-10 levels are correlated with disease progression on longitudinal testing. Previously, HIV and HIV peptides have been found to enhance IL-10 production from mononuclear cells in vitro [21, 32]. In the present study we demonstrate that persistent high circulating IL-10 levels are a characteristic feature of HIV infection also in vivo and may be of pathogenic importance in the progression of HIV-related disease.

Progressive immunodeficiency and susceptibility to opportunistic infections are hallmarks of AIDS. MAC represents one of the most important intracellular pathogens in AIDS patients and is associated with high morbidity and mortality [33]. We found that AIDS patients with ongoing MAC infection had significantly higher IL-10 levels than both AIDS patients without clinical events and AIDS patients with PCP or CMV infection. We have recently demonstrated enhanced IL-10 production in vitro in response to MAC products in mononuclear cells from HIV-infected patients [34], and the present study suggests that an enhanced IL-10 response to MAC also occurs in vivo. Immunosuppressive effects of high IL-10 levels, e.g. impaired Th1 responses and monocyte function [4–7], may well contribute to reduced immunity to intracellular microorganisms and may favour MAC survival in HIV-infected patients. The combined stimulatory effects of HIV [21, 32] and MAC [34] on IL-10 release may possibly explain the markedly enhanced IL-10 levels in AIDS patients with MAC infection. The high IL-10 levels may in turn further enhance MAC and thereby also HIV replication [35], which again may further increase IL-10 levels, possibly representing a vicious circle. Thus, we believe that the elevated IL-10 levels in AIDS patients with MAC infection may represent an important pathogenic feature in these patients, in particular since they also are characterized by markedly raised TNF-α levels [36].

Several reports have suggested that a shift in cytokine pattern from Th1- to Th2-related cytokines may contribute to disease progression in HIV infection [12–15]. Recently, we have suggested that raised IL-10 levels may reflect enhanced monocyte activity rather than a shift from Th1 to Th2 profile [34]. Whatever the cellular sources, high IL-10 levels may be of pathogenic importance also in HIV-infected non-MAC patients, e.g. by reducing functional lymphocyte responses to antigens, which are detectable in asymptomatic HIV infection long before decline in CD4+ T cell counts [14, 37]. Furthermore, IL-10 is an important ‘deactivator’ of macrophages [4, 5], and high IL-10 levels may impair the microbicidal capacity of these cells, as discussed above. However, the biological effect of IL-10 is also dependent on interaction with other cytokines, in particular inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α [4, 24, 25, 29, 30]. Thus, IL-10 in concentrations that suppress TNF-α levels appears to inhibit HIV replication in macrophages [24], and has also been claimed to suppress plasma viraemia after one bolus injection in HIV-infected patients [30]. However, in the same in vitro models lower concentrations of IL-10, unable to suppress endogenous production of inflammatory cytokines completely, paradoxically enhanced TNF-α-induced HIV replication. Also, IL-10 has been shown to both inhibit and promote apoptosis of T cells [23, 38], and again these apparently contradictory effects may depend on the relative balance between IL-10 and inflammatory cytokines. In the present study we found that increasing IL-10 and TNF-α levels were associated with disease progression in both cross-sectional and longitudinal testing. However, our findings concerning the IL-10/TNF-α ratio suggest that the balance between these cytokines may be of pathogenic importance in the progression of HIV-related disease.

Treatment of HIV-infected patients with HAART has been shown to have a profound down-regulatory effect on HIV replication in vivo, with concomitant increases in CD4+ and CD8+ T cell counts [39, 40]. In the present study we report that HAART also induced decreased levels of IL-10, but this decrease was more gradual than the response observed for viral load and CD4+ T cell counts and TNF-α [31]. Furthermore, a lack of decline in IL-10 levels was associated with virologic treatment failure. Finally, although there was a significant fall in IL-10 levels during HAART, there was no normalization compared with levels in healthy controls. This observation supports the notion that full immunological normalization may not be achieved during such therapy.

The potential role of IL-10 in the pathogenesis of HIV disease has been under intensive study, but this role is still unclear. The present study demonstrates increasing serum levels of IL-10 along with disease progression in HIV-infected patients and a fall in IL-10 levels during HAART. This lends further credence to the hypothesis that IL-10 may play a significant role in the pathogenesis of HIV disease. Our results suggest a possible role for immunomodulating therapy which down-regulates IL-10 activity in addition to concomitant HAART in HIV-infected patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Research Council of Norway, the Norwegian Cancer Society, Anders Jahre's Foundation, Medinnova Foundation and Odd Kåre Rabben's Memorial Found for AIDS Research. The authors thank Bodil Lunden, Lisbeth Wikeby and Vigdis Bjerkeli for excellent technical assistance and Knut Lerpold for help in the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Fiorentino DF, Bond MW, Mosmann TR. Two types of mouse T helper cell. IV. Th2 clones secrete a factor that inhibits cytokine production by Th1 clones. J Exp Med. 1989;170:2081–5. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.6.2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benjamin D, Knobloch TJ, Dayton MA. Human B-cell lines derived from patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and Burkitts lymphoma constitutively secrete large quantities of interleukin-10. Blood. 1992;80:1289–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burdin N, Peronne C, Banchereau J, Rousset F. Epstein–Barr virus transformation induces B lymphocytes to produce human interleukin 10. J Exp Med. 1993;177:295–304. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.2.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore KWO, Garra A, de Waal Malefyt R, Vieira R, Mosmann TR. Interleukin-10. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11:165–9. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.001121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mosmann TR. Properties and functions of interleukin-10. Adv Immunol. 1994;56:1–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Waal Malefyt R, Haanen J, Spits H, et al. Interleukin 10 (IL-10) and viral IL-10 strongly reduced antigen-specific human T cell proliferation by diminishing the antigen-presenting capacity of monocytes via down-regulation of class major histocompatibility complex expression. J Exp Med. 1991;174:915–24. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.4.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiorentino DF, Zlotnic A, Viera P, et al. IL-10 acts on the antigen presenting cell to inhibit cytokine production by Th1 cells. J Immunol. 1991;146:3444–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mosmann TR, Cherwinski H, Bond MW, Giedlin MA, Coffman RL. Two types of murine helper T cell clone. I. Definition according to profiles of lymphocytokine activities and secreted proteins. J Immunol. 1986;136:2348–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Del Prete GF, De Carli M, Maustromaro C, et al. Purified protein derivative of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and excretory/secretory antigen(s) of Toxocara canis expand in vitro T cells with stable and opposite (type 1 T helper or type 2 T helper) profile of cytokine production. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:346–50. doi: 10.1172/JCI115300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romagnani S. Biology of human Th1 and Th2 cells. J Clin Immunol. 1995;15:121–9. doi: 10.1007/BF01543103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abbas AK, Murphy KM, Sher A. Functional diversity of helper T lymphocytes. Nature. 1996;383:787–93. doi: 10.1038/383787a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clerici M, Shearer GM. The Th1-Th2 hypothesis of HIV infection: new insights. Immunol Today. 1994;15:575–81. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barcellini W, Rizzardi GP, Borghi MO, Fain C, Lazzarin A, Meroni PL. Th1 and Th2 cytokine production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells from HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 1994;8:757–62. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199406000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clerici M, Wynn TA, Berzofsky JA, et al. Role of interleukin-10 in T helper cell dysfunction in asymptomatic individuals infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:768–75. doi: 10.1172/JCI117031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jason J, Sleeper LA, Donfield SM, et al. Evidence for a shift from a type 1 lymphocyte pattern with HIV disease progression. J AIDS Hum Retrovir. 1995;10:471–6. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199512000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meroni L, Trabattoni D, Balotta C, et al. Evidence for type 2 cytokine production and lymphocyte activation in the early phases of HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 1996;10:23–30. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199601000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romagnani S, Maggi E, del Prete G. An alternative view of the Th1/Th2 switch hypothesis in HIV infection. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1994;10:3–9. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.iii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maggi E, Mazztti M, Ravina A, et al. Ability of HIV to promote a Th1 to Th2 shift and to replicate preferentially in Th2 and Th0 cells. Science. 1994;265:244–8. doi: 10.1126/science.8023142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graziosi C, Pantaleo G, Gantt KR, et al. Lack of evidence for the dichotomy of Th1 and Th2 predominance in HIV-infected patients. Sci. 1994;265:248–52. doi: 10.1126/science.8023143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daftarian MP, Diaz-Mitoma F, Creery WD, Cameron W, Kumar A. Dysregulated production of interleukin-10 (IL-10) and IL-12 by peripheral blood lymphocytes from human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals is associated with altered proliferative responses to recall antigens. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1995;2:712–8. doi: 10.1128/cdli.2.6.712-718.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akridge RE, Oyafuso LKM, Reed SG. IL-10 is induced during HIV-1 infection and is capable of decreasing viral replication in human macrophages. J Immunol. 1994;153:5782–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diaz-Mitoma F, Kumar A, Karimi S, et al. Expression of IL-10, IL-4 and interferon-gamma in unstimulated and mitogen-stimulated peripheral blood lymphocytes from HIV-seropositive patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;102:31–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb06632.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taga K, Cherney B, Tosato G. IL-10 inhibits apoptotic cell death in human T cells starved of IL-2. Int Immunol. 1993;5:1599–608. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.12.1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weissman DP, Poli G, Fauci AS. Interleukin 10 blocs HIV replication in macrophages by inhibiting the autocrine loop of TNF-α and IL-6 induction of virus. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1994;10:1199–206. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weissman D, Poli G, Fauci AS. IL-10 synergizes with multiple cytokines in enhancing HIV production in cells of monocytic lineage. J AIDS Hum Retrovir. 1995;9:442–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1993 revised classification for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. MMWR. 1992;41:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aukrust P, Liabakk NB, Muller F, Lien E, Espevik T, Frøland SS. Serum levels of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and soluble TNF receptors in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection—correlations to clinical, immunologic, and virologic parameters. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:420–4. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brinchman JE, Vartal F, Gaudernak G, et al. Direct immunomagnetic quantification of lymphocyte subsets in blood. Clin Exp Immunol. 1988;71:182–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Poll T, Jansen J, Levi M, ten Cate H, ten Cate JW, van Deventer SJH. Regulation of interleukin 10 release by tumor necrosis factor in human and chimpanzees. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1985–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.5.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fauci AS. Host factors and the pathogenesis of HIV-induced disease. Nature. 1996;384:529–34. doi: 10.1038/384529a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aukrust P, Muller F, Lien E, et al. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) system in HIV-infected patients during highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART)-persistent TNF activation is associated with virologic and imunologic treatment failure. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:74–82. doi: 10.1086/314572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taaoufik Y, Lantz O, Wallon C, Charles A, Dussaix E, Delfraissy JF. Human immunodeficiency virus gp120 inhibits interleukin-12 secretion by human monocytes: an indirect interleukin-10-mediated effect. Blood. 1997;89:2842–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benson CA, Ellner JJ. Mycobacterium-avium complex infection and AIDS—advances in theory and practice. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:7–20. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muller F, Aukrust P, Lien E, Haug CJ, Espevik T, Frøland SS. Enhanced interleukin-10 production in response to Mycobacterium avium products in mononuclear cells from patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:586–94. doi: 10.1086/514222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghassemi M, Andersen BR, Reddy VM, Gangadharam PR, Spear GT, Novak RM. Human immunodeficiency virus and Mycobacterium avium complex coinfection of monocytoid cells results in reciprocal enhancement of multiplication. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:68–73. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haug CJ, Aukrust P, Lien E, Muller F, Espevik T, Frøland S. Disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex infection in AIDS: significance of an activated tumor necrosis factor system and depressed serum levels of 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D. J Inf Dis. 1995;173:259–62. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.1.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miedema F, Petit AJ, Terpstra FG, et al. Immunological abnormalities in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected asymptomatic homosexual men. HIV affects the immune system before CD4+ T helper cell depletion occurs. J Clin Invest. 1988;82:1908–16. doi: 10.1172/JCI113809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Georgescu L, Vakkalanka RK, Elkon KB, Crow MK. Interleukin-10 promotes activation-induced cell death of SLE lymphocytes mediated by Fas ligand. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2622–33. doi: 10.1172/JCI119806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kelleher AD, Carr A, Zaunders J, Cooper DA. Alterations in the immune response of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected subjects treated with an HIV-specific protease inhibitor, ritonavir. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:321–9. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cameron WD, Heath-Chiozzi M, Danner S, et al. Randomised placebo-controlled trial of ritonavir in advanced HIV-disease. Lancet. 1998;351:543–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)04161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]