Abstract

The possible relation between HLA-DQ genotypes and both frequencies and levels of autoantibodies associated with IDDM was assessed by examining HLA-DQB1 alleles and antibodies to islet cells (ICA), insulin (IAA), glutamic acid decarboxylase (GADA) and the protein tyrosine phosphatase-related IA-2 molecule (IA-2A) in 631 newly diagnosed diabetic children under the age of 15 years. ICA were found in 530 children (84.0%), while close to half of the subjects (n = 307; 48.7%) tested positive for IAA. GADA were detected in 461 index cases (73.1%), with a higher frequency in those older than 10 years (78.9% versus 69.2% in the younger ones; P = 0.006). More than 85% of the children (n = 541; 85.7%) tested positive for IA-2A. Altogether there were only 11 children (1.7%) who had no detectable autoantibodies at diagnosis. There were no differences in the prevalence of ICA or GADA between four groups formed according to their HLA-DQB1 genotype (DQB1*0302/02, *0302/X (X = other than *02), *02/Y (Y = other than *0302) and other DQB1 genotypes). The children with the *0302/X genotype had a higher frequency of IA-2A and IAA than those carrying the *02/Y genotype (93.8% versus 67.3%, P < 0.001; and 49.0% versus 33.6%, P = 0.002, respectively). The children with the *02/Y genotype had the highest GADA levels (median 36.2 relative units (RU) versus 14.9 RU in those with *0302/X; P = 0.005). Serum levels of IA-2A and IAA were increased among subjects carrying the *0302/X genotype (median 76.1 RU versus 1.6 RU, P = 0.001; and 50 nU/ml versus 36 nU/ml, P = 0.004) compared with those positive for *02/Y. Only three out of 11 subjects homozygous for *02 (27.3%) tested positive for IA-2A, and they had particularly low IA-2A (median 0.23 RU versus 47.6 RU in the other subjects; P < 0.001). The distribution of HLA-DQB1 genotypes among autoantibody-negative children was similar to that in the other patients. These results show that DQB1*0302, the most important single IDDM susceptibility allele, is associated with a strong antibody response to IA-2 and insulin, while GAD-specific humoral autoimmunity is linked to the *02 allele, in common with a series of other autoimmune diseases as well as IDDM. We suggest that IA-2A may represent β cell-specific autoimmunity, while GADA may represent a propensity to general autoimmunity.

Keywords: insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, HLA-DQB1, islet cell antibodies, insulin autoantibodies, antibodies to the 65-kD isoform of glutamic acid decarboxylase, antibodies to the protein tyrosine phosphatase-related IA-2 antigen

INTRODUCTION

IDDM is thought to be an autoimmune disease with an immunogenetic regulation [1]. The destruction process of the pancreatic β cells which precedes the clinical onset of the disease may be provoked by environmental factors accompanied by cellular and humoral immune responses directed against the insulin-producing cells. Autoantibodies to islet cell antigens, including cytoplasmic structures (ICA), insulin (IAA), the 65-kD isoform of glutamic acid decarboxylase (GADA), and the protein tyrosine phosphatase-related IA-2 molecule (IA-2A) have been reported to precede the clinical manifestation of IDDM by several years [2–5]. The genetic background of the disease is complex, although the major genetic susceptibility to IDDM has been located in the MHC region on the short arm of chromosome 6, particularly its class II HLA genes [6]. Convincing evidence has accumulated to suggest that the HLA-DR and DQ loci confer genetic susceptibility to IDDM, with the DR4-DQB1*0302/DR3-DQB1*02 genotype encoding the highest risk, and DR2-DQB1*0602–3 providing a strong protective effect [7–9]. About 90% of the Caucasian population with IDDM have DQB1*0302 and/or DQB1*02, compared with < 40% in the control subjects. The molecular mechanisms of this HLA defined genetic predisposition remain to be defined, however.

To test the hypothesis that a strong genetic susceptibility to IDDM is associated with aggressive autoimmunity directed against the pancreatic β cells and reflected in high levels of disease-related autoantibodies, we typed an extensive population of children with newly diagnosed IDDM for five HLA-DQB1 alleles and measured their serum levels of ICA, GADA, IAA and IA-2A. An additional objective was to explore whether subjects with no detectable disease-associated autoantibodies at diagnosis represent a genetically conventional type of IDDM.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Subjects

The population comprised 631 children under 15 years of age out of a total of 801 probands (78.8%) in whom IDDM was diagnosed during the recruitment period of the Childhood Diabetes in Finland (DiMe) Study, from September 1 1986 to April 30 1989. The study population included all index cases with available HLA-DQB1 genotyping data. The background and design of this study have been described in detail previously [10]. The mean age of the diabetic children was 8.5 years (range 0.8–15.0 years), and 55.5% of them were boys (n = 350). Blood samples were taken at the diagnosis before the first insulin injection. Sera were stored at −20°C until analysis. The research design was approved by the ethical committees of all the participating hospitals.

Methods

Autoantibody determinations

ICA were determined by a standard immunofluorescence method using sections of frozen human group O pancreas [11]. End point dilution titres were examined for the positive samples and the results were expressed in Juvenile Diabetes Foundation (JDF) units relative to an international reference standard [12]. The detection limit was 2.5 JDF units. Our laboratory has participated in the international workshops on the standardization of the ICA assay, in which its sensitivity was 100%, specificity 98%, validity 98% and consistency 98% in the fourth round.

IAA levels were analysed with a radiobinding assay modified from that described by Palmer et al. [13]. Endogenous insulin was removed with acid charcoal prior to the assay, and free and bound insulin were separated after incubation with mono-125I(TyrA14)-human insulin (Novo Research Institute, Bagsvaerd, Denmark) for 20 h in the absence or presence of an excess of unlabelled insulin. The IAA levels were expressed in nU/ml, where 1 nU/ml corresponds to a specific binding of 0.01% of the total counts. The interassay coefficient of variation was < 8%. A subject was considered to be positive for IAA when the specific binding exceeded 54 nU/ml (99th percentile in 105 non-diabetic subjects). The disease sensitivity of the IAA assay was 26%, and the disease specificity 97% based on 140 samples included in the 1995 Multiple Autoantibody Workshop [14].

GADA were measured with a modification [15] of the radiobinding assay described by Petersen et al. [16]. The results were expressed in relative units (RU), representing the specific binding as a percentage of that obtained with a positive standard serum. The cut-off limit for antibody positivity was set at the 99th centile in 372 non-diabetic Finnish children and adolescents, i.e. 6.6 RU. The intra-assay coefficient of variation was < 5%, and the interassay coefficient < 10%. The disease sensitivity of the GADA assay was 79% and its specificity 97%, based on the 1995 Multiple Autoantibody Workshop [14].

IA-2A were quantified with a radiobinding assay as previously described [17]. The results were expressed as RU based on a standard curve run on each plate using an automated calculation program (MultiCalc; Wallac, Turku, Finland). The limit for IA-2A positivity (0.43 RU) was set at the 99th percentile in 374 non-diabetic Finnish children and adolescents. The interassay coefficient of variation was < 12%. This assay had a disease sensitivity of 62% and a specificity of 97% based on 140 samples included in the Multiple Autoantibody Workshop [14].

HLA-DQB1 typing was performed by a recently described method based on time resolved fluorescence [18]. The second exon of the DQB1 gene was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and the product subsequently hybridized with four lanthanide-labelled, sequence-specific oligonucleotide probes identifying the following alleles known to be significantly associated with either susceptibility or protection against IDDM: DQB1*0302, *02, *0301 and *0602–03. The index cases were classified into four groups based on their genotype: DQB1*0302/02, *0302/X (X = other than *02), *02/Y (Y = other than *0302) and other DQB1 genotypes. In addition, patients homozygous for *0302 or *02 were identified based on the parental alleles. Those carrying the protective DQB1*0602 and *0603 alleles were also compared with the remaining subjects.

Statistical analysis

The data were evaluated statistically with cross-tabulation and χ2 statistics, the Kruskall–Wallis one-way analysis of variance with post hoc testing of differences between two groups, when indicated, and the Mann–Whitney U-test. Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was performed, where appropriate. The results are expressed as proportions (95% confidence intervals (CI)) or medians (range), if not otherwise indicated. In addition we performed multiple regression analyses with antibody positivity and antibody levels as dependent variables and sex, age, and DQB1 alleles as independent variables. All the analyses were performed using the SPSS software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Autoantibodies, sex, and age

ICA were detected in 530 index cases (84.0% (CI 81.2–86.9%)), their level ranging from 2.5 to 2473 JDF units with a median of 36 JDF units. The frequency of ICA was similar in boys and girls, but the patients under the age of 10 years tested more often positive for ICA than the older ones (88.4% (CI 85.1–91.6%) versus 77.3% (CI 72.0–82.2%); P < 0.001). Close to half of the children tested positive for IAA [307; 48.7% (CI 44.8–52.6%)) with a level ranging from 55 to 3315 nU/ml and a median of 146 nU/ml. IAA were detected at a higher frequency in the children under the age of 5 years than in the older ones (73.9% (CI 66.6–81.2%) versus 41.3% (CI 36.9–45.7%); P < 0.001).

There were 461 index cases (73.1% (CI 69.6–76.5%)) who had detectable GADA at diagnosis, the levels ranging from 6.6 to 197.1 RU with a median of 20.1 RU. There was no sex difference between GADA-positive and -negative children among those more than 10 years of age, but among the younger ones the girls tested more often positive for GADA than the boys (74.2% (CI 67.6–80.6%) versus 64.9 (CI 58.2–71.4%); P = 0.05). GADA were more frequent in those older than 10 years (78.9% (CI 73.8–83.9%) versus 69.2% (CI 64.5–73.8%) in those under the age of 10 years; P = 0.007). Five hundred and forty-one probands (85.7% (CI 83.0–88.5%)) tested positive for IA-2A with a median antibody level of 45.0 RU (range 0.68–2801 RU). Multiple autoantibodies (three or more) were observed in 484 cases (77.2%). Children younger than 5 years had multiple autoantibodies more often than did the older ones (80.3% (CI 73.7–86.9%) versus 68.9% (CI 64.8–73.0%); P = 0.01).

HLA-DQB1 genotypes and autoantibodies

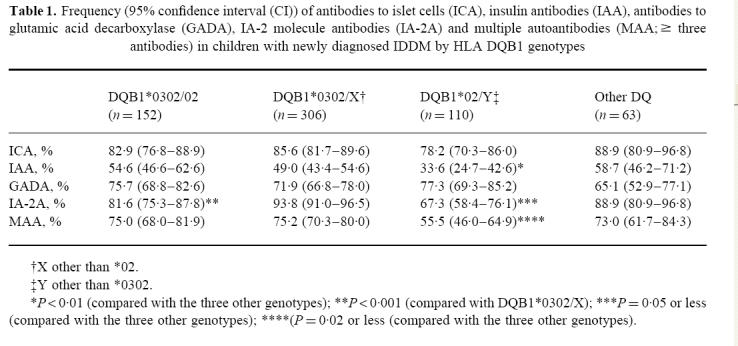

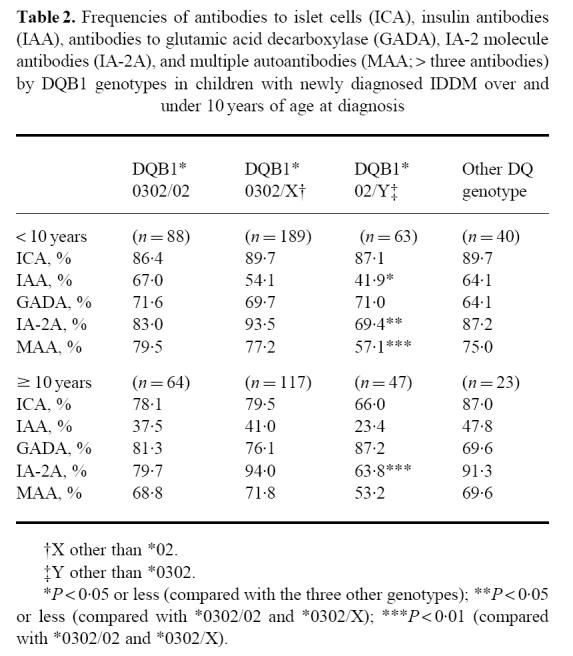

One hundred and fifty-two subjects were HLA-DQB1*0302/02 heterozygotes (24.1%), 306 carried the *0302/X genotype (48.5%) and 110 the *02/Y genotype (17.4%), while the remaining 63 patients had other genotypes (10.0%). There were no significant differences in the proportion of children testing positive for ICA or GADA between the four genotype groups (Table 1), but cases carrying the *02/Y genotype had a decreased frequency of IAA and IA-2A and less often tested positive for multiple autoantibodies than those with the other genotypes. The prevalence of IA-2A was particularly low in the 11 patients homozygous for DQB1*02 (27.3% (CI 4.1–58.6%) versus 71.7% (95% CI 62.6–80.7%) among those with the heterozygous *02/Y genotype; P < 0.001). When analysing subjects less than 10 years old at diagnosis, similar differences could be seen in the frequencies of IAA and multiple autoantibodies between the four genotypes as those observed in the total population, while these differences could not be observed among those older than 10 years (Table 2). IA-2A remained less frequent among those with the *02/Y genotype in both age groups.

Table 1.

Frequency (95% confidence interval (CI)) of antibodies to islet cells (ICA), insulin antibodies (IAA), antibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase (GADA), IA-2 molecule antibodies (IA-2A) and multiple autoantibodies (MAA; ≥ three antibodies) in children with newly diagnosed IDDM by HLA DQB1 genotypes

|

Table 2.

Frequencies of antibodies to islet cells (ICA), insulin antibodies (IAA), antibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase (GADA), IA-2 molecule antibodies (IA-2A), and multiple autoantibodies (MAA; > three antibodies) by DQB1 genotypes in children with newly diagnosed IDDM over and under 10 years of age at diagnosis

|

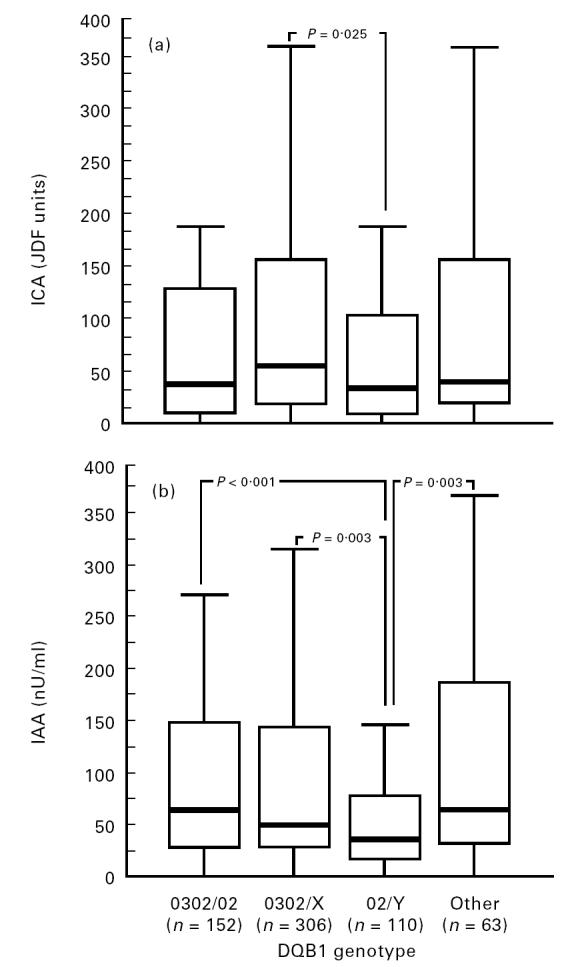

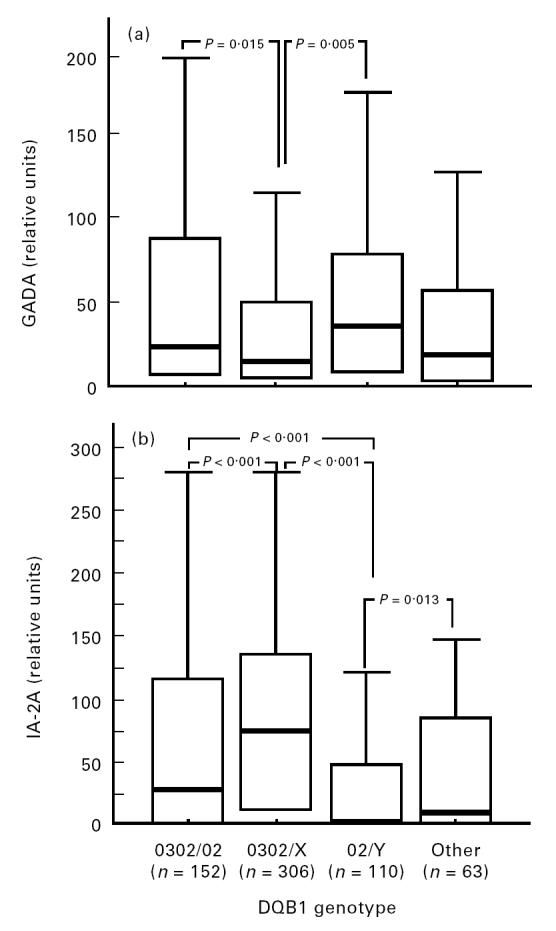

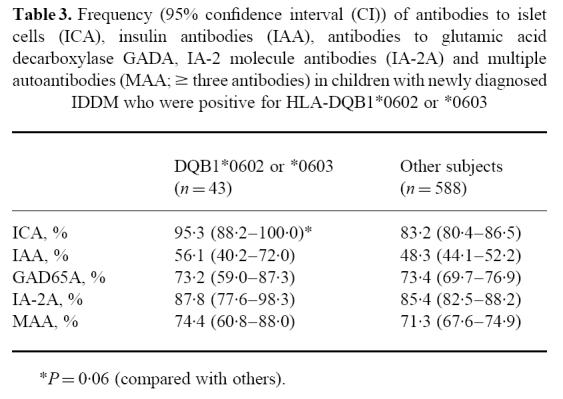

The children carrying the DQB1*0302/X genotypes had higher ICA levels than those with DQB1*02/Y, but lower GADA levels than those carrying *0302/02 or *02/Y (Figs 1 and 2). Cases that were positive for *02/Y had lower IAA and IA-2A levels than the other three genotypes (Figs 1 and 2). The lowest IA-2A levels were seen in the subjects who were homozygous for DQB1*02 (median 0.32 RU (range 0.13–48.6 RU) versus 2.39 RU (range 0.11–564 RU) in the *02/Y heterozygous patients; P = 0.01, and versus 59.6 RU (range 0.08–2801 RU) in all other patients; P < 0.001). The probands carrying the protective DQB1*0602 or *0603 alleles had an increased frequency of ICA (Table 3) and higher antibody levels than the remaining patients (71 versus 36 JDF units; P = 0.007).

Fig 1.

Antibody to islet cells (ICA) (a) and insulin antibody (IAA) (b) levels in 631 index cases according to their HLA-DQB1 genotypes. Each box plot represents the median (——), the 25th and the 75th centiles. The error bars represent the smallest and the largest observed values that are not outliers.

Fig 2.

Antibody to glutamic acid decarboxylase (GADA) (a) and IA-2 molecule antibody (IA-2A) (b) levels in 631 index cases according to their HLA-DQB1 genotypes. Each box plot represents the median (——), the 25th and 75th centiles. The error bars represent the smallest and the largest observed values that are not outliers.

Table 3.

Frequency (95% confidence interval (CI)) of antibodies to islet cells (ICA), insulin antibodies (IAA), antibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase GADA, IA-2 molecule antibodies (IA-2A) and multiple autoantibodies (MAA; ≥ three antibodies) in children with newly diagnosed IDDM who were positive for HLA-DQB1*0602 or *0603

|

There were altogether 11 subjects who tested negative for all four disease-associated autoantibodies at diagnosis. Two carried the DQB1*0302/02 genotype, five the *0302/X genotype, and three the *02/Y genotype, and only one had a protective genotype. Accordingly the distribution of DQB1 genotypes in these children was similar to that among antibody-positive subjects.

Relation between autoantibodies, sex, age and HLA-DQB1 alleles

In a multiple regression model with sex, age and HLA-DQB1 alleles as independent variables, ICA were inversely related to age (P < 0.05). There was also an inverse relation between IAA and both age (P < 0.001) and HLA-DQB1*02 (P < 0.05). GADA levels were associated with female sex (P < 0.001) and age (P < 0.001), but not with HLA-DQB1*02. We could not find any significant relationship between IA-2A and any of the dependent variables in the multiple regression model.

DISCUSSION

We set out in this population-based study to explore whether strong HLA-DQB1-defined disease susceptibility is associated with an aggressive autoimmune process in the form of high frequencies and levels of IDDM-related autoantibodies. The results indicate that the HLA-DQB1 genotype may have a modifying influence on the expression of disease-associated autoantibodies, but there is no clear evidence of a simple linear relation between genetic disease susceptibility and the intensity of the humoral immune response to β cell antigens, although we observed a decrease in the prevalence and levels of IAA from the high risk *0302/02 genotype down to the low risk *02/Y genotype. This trend was diffracted by a higher frequency and increased levels of IAA in children carrying neutral or protective genotypes. Patients with strong genetic disease protection had both an increased prevalence and high levels of ICA, suggesting that the genetic disease protection can be broken by a strong autoimmune reaction.

The present results are largely concordant with most previous findings on the association between HLA class II alleles and IDDM-related autoantibodies. Ziegler et al. reported a substantially higher frequency of IAA and higher levels in patients with newly diagnosed IDDM carrying the DR4 allele, especially in those who were DR4 homozygous [19]. A relatively strong association was observed between the DQA1*0301-DQB1*0302 haplotype and IAA and high titre ICA in recent-onset patients in a Belgian study [20]. Our observations are also in line with those of Hagopian et al. [21], who found that GADA were associated with DQB1*02 and IAA with DQB1*0302 in Swedish IDDM children studied at the time of diagnosis. A recent Italian study reported that IA-2A were more prevalent in newly diagnosed patients carrying the DR4 allele, while DR3+ cases had more often and higher levels of GADA [22]. The most novel observation in the present survey is the conspicuously low frequency and levels of IA-2A in the few patients who were homozygous for DQB1*02, indicating that this trait carries relatively strong protection against an antibody response to the IA-2 molecule.

According to our observations and those of others [21, 22], there are differences in the autoantibody profile between those carrying the *0302/X genotype and cases with the *02/Y genotype, the former being characterized by increased IAA and IA-2A concentrations but low GADA levels, whereas low IAA and IA-2A levels and increased GADA concentrations are typical for the latter cases. The DR3/DQB1*02 haplotype has been reported to be associated with a milder presentation and natural course of the disease [23, 24]. High GADA levels have also been observed in patients with multiple autoimmune endocrinopathies, in whom they seem to be related to infrequent, retarded progression to clinical IDDM [25]. These findings in combination with the present results raise the issue whether high GADA levels are markers of a propensity to a strong humoral autoimmune reactivity rather than of specific β cell destruction.

Females have previously been shown to test positive for GADA more often than males [15], and in the present series this could be confirmed in those less than 10 years of age at diagnosis. No gender associations have been observed for the other disease-related autoantibodies. In contrast, an inverse correlation has been demonstrated repeatedly between age and both ICA and particularly IAA [15, 20,26–28]. Gorus et al. reported IA-2A to be more prevalent among patients diagnosed under the age of 20 years compared with older patients [29], but we were unable to detect any effect of age on the frequency of IA-2A among children presenting with IDDM before the age of 15 years [17]. In the present series we confirmed in a multiple regression analysis the previous observations that positivity for IAA and ICA is related to young age, whereas GADA are associated with older age and female gender. In the multiple regression model there was an inverse relation between IAA positivity and the presence of the DQB1*02 allele, while the associations between GADA and the DQB1*02 allele and between IA-2A and the DQB1*0302 allele could not be verified in the multiple regression model. This observation indicates that the relationship between autoantibodies, genetic markers and demographic characteristics is complicated and affected by factors not included in the present analysis. In a Belgian study is has been shown, for example, that GADA are associated with the insulin gene polymorphism predisposing to IDDM in patients carrying the DQA1*05-DQB1*02 combination and with clinical disease onset after the age of 20 years [30].

The observation that the DQB1 genotype distribution among children with recent-onset IDDM without signs of humoral β cell autoimmunity is identical to that among those testing positive for one or more autoantibodies suggests that these children have the same disease, at least genetically. It has been speculated that children testing negative for autoantibodies at diagnosis would represent a distinct form of diabetes, either non-immune IDDM or some of the recently characterized maturity-onset diabetes in the young syndromes [31]. The present findings do not provide any evidence for such speculations, and prospective observation of prediabetic siblings has shown that a small proportion of the progressors may turn autoantibody-negative before clinical diagnosis, although they test positive for one or more autoantibodies earlier during the prediabetic process [32].

Our results fit well into a pathogenic model of IDDM, where the genetic elements either facilitate or protect against the initiation of β cell destruction by an exogenous agent. The intensity and pace of the autoimmune destruction is probably mainly regulated by various host and environmental factors, but may be modified by disease susceptibility genes. The present observations suggest that in the presence of protective HLA-DQB1 alleles, a strong autoimmune reaction manifested by high ICA levels is needed to break the protection and lead to progressive target cell destruction and clinical disease.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Foundation for Diabetes Research in Finland, the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation International (grants 188517 and 197032), the Novo Nordisk Foundation, and the Medical Research Council, the Academy of Finland (grant 26109). E.S. was a recipient of a grant from the Centre for International Mobility (CIMO), Helsinki, Finland. The ‘Childhood Diabetes in Finland’ project has been supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (grant DK-37957), the Sigrid Jusélius Foundation, the Association of Finnish Life Insurance Companies, the University of Helsinki and Novo Nordisk A/S, Bagsvaerd, Denmark. The authors thank Susanna Heikkilä, Sirpa Anttila, Riitta Päkkilä and Päivi Koramo for their skilful technical assistance. The Childhood Diabetes in Finland (DiMe) Study Group has the following members: Principal investigators: H.K. Åkerblom, J. Tuomilehto; Co-ordinators: R. Lounamaa, L. Toivonen; Data management: E. Virtala, J. Pitkäniemi; Local investigators: A. Fagerlund, M. Flittner, B. Gustafsson, M. Häggquist, A. Hakulinen, L. Herva, P. Hiltunen, T. Huhtamäki, N.-P. Huttunen, T. Huupponen, T. Joki, R. Jokisalo, M.-L. Käär, S. Kallio, E. A. Kaprio, U. Kaski, M. Knip, L. Laine, J. Lappalainen, J. Mäenpää, A.-L. Mäkelä, K. Niemi, A. Niiranen, A. Nuuja, P. Ojajärvi, T. Otonkoski, K. Pihlajamäki, S. Pöntynen, J. Rajantie, J. Sankala, J. Schumacher, M. Sillanpää, M.-R. Ståhlberg, C.-H. Stråhlmann, T. Uotila, M. Väre, P. Varimo, G. Wetterstrand; Special investigators: A. Aro, M. Hiltunen, H. Hurme, H. Hyöty, J. Ilonen, J. Karjalainen, M. Knip, P. Leinikki, A. Miettinen, T. Petäys, L. Räsänen, H. Reijonen, A. Reunanen, T. Saukkonen, E. Savilahti, E. Tuomilehto-Wolf, P. Vähäsalo, S. M. Virtanen.

References

- 1.Atkinson MA, Maclaren NK. What causes diabetes? Sci Am. 1990;263:62–71. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0790-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tarn AC, Thomas JM, Dean BM, Ingram D, Schwartz G, Bottazzo GF, Gale EA. Predicting insulin-dependent diabetes. Lancet. 1988;2:845–50. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91601-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christie MR, Tun RY, Lo SS, et al. Antibodies to GAD and tryptic fragments of islet 64K antigen as distinct markers for development of IDDM. Studies with identical twins. Diabetes. 1992;41:782–7. doi: 10.2337/diab.41.7.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karjalainen J, Vähäsalo P, Knip M, Tuomilehto-Wolf E, Virtala E, Åkerblom HK. the Childhood Diabetes in Finland Study Group. Islet cell autoimmunity and progression to insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in high- and low-risk siblings of diabetic children. Eur J Clin Invest. 1996;26:640–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1996.tb02147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verge CF, Gianini R, Kawasaki E, Yu L, Pietropaolo M, Jackson RA, Chase HP, Eisenbarth GS. Prediction of type 1 diabetes in first-degree relatives using a combination of insulin, GAD and ICA512bdc/IA-2 antibodies. Diabetes. 1996;45:926–33. doi: 10.2337/diab.45.7.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nepom GT. Class II antigens and disease susceptibility. Ann Rev Med. 1995;46:17–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.46.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheehy MJ, Schart SJ, Rowe JR, Neme de Gimenez MH, Meske LM, Erlich HA, Nepom BS. A diabetes susceptible HLA haplotype is best defined by a combination of HLA-DR and -DQ alleles. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:830–5. doi: 10.1172/JCI113965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baisch JM, Weeks T, Giles R, Hoover M, Stastny P, Capra JD. Analysis of HLA-DQ genotypes and susceptibility in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:836–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199006283222602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kockum I, Wassmuth R, Holmberg E, Michelsen B, Lernmark Å. HLA primarily confers protection and HLA-DR susceptibility in type I (insulin dependent) diabetes studied in population-based affected families and controls. Am J Hum Genet. 1993;53:150–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tuomilehto J, Lounamaa R, Tuomilehto-Wolf E, Reunanen A, Virtala E, Kaprio EA, Åkerblom HK. Epidemiology of childhood diabetes mellitus in Finland—background of a nationwide study of type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1992;35:70–76. doi: 10.1007/BF00400854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bottazzo GF, Florin-Christensen A, Doniach D. Islet-cell antibodies in diabetes mellitus with autoimmune polyendocrine deficiencies. Lancet. 1974;2:1279–82. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)90140-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lernmark Å, Molenaar JL, van Beers WA, Yamaguchi Y, Nagataki S, Ludvigsson J, Maclaren NK. The fourth international serum exchange workshop to standardize cytoplasmic islet cell antibodies. Diabetologia. 1991;34:534–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00403293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palmer JP, Asplin CM, Clemons P, Lyen K, Tatpati O, Raghu PK, Paquette TL. Insulin antibodies in insulin-dependent diabetics before insulin treatment. Sci. 1983;222:1337–9. doi: 10.1126/science.6362005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verge CF, Stenger D, Bonifacio E, Colman PG, Pilcher C, Bingley PJ, Eisenbarth GS. participating laboratories. Combined use of autoantibodies (IA-2ab, GADab, IAA, ICA) in type 1 diabetes: combinatorial islet autoantibody workshop. Diabetes. 1998;47:1857–66. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.12.1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sabbah E, Kulmala P, Veijola R, et al. Glutamic acid decarboxylase antibodies in relation to other autoantibodies and genetic risk markers in children with newly diagnosed insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:2455–9. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.7.8675560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petersen JS, Hejnaes KR, Moody A, et al. Detection of GAD65 antibodies in diabetes and other autoimmune diseases using a simple radioligand assay. Diabetes. 1994;43:459–67. doi: 10.2337/diab.43.3.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Savola K, Bonifacio E, Sabbah E, et al. IA-2 antibodies—a sensitive marker of IDDM with clinical onset in childhood and adolescence. Diabetologia. 1998;41:424–9. doi: 10.1007/s001250050925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sjöroos M, Iiitiä A, Ilonen J, Reijonen H, Lövgren T. Triple-label hybridization assay for type-1 diabetes-related HLA alleles. Biotechniques. 1995;18:870–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ziegler AG, Standl E, Albert E, Mehner H. HLA associated insulin autoantibody formation in newly diagnosed type 1 diabetic patients. Diabetes. 1991;40:1146–9. doi: 10.2337/diab.40.9.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vandewalle CL, Decraene T, Schuit FCDE, Leeuw IH, Pipeleers DG, Gorus FK. Insulin autoantibodies and high titre islet cell antibodies are preferentially associated with the HLA DQA1*0301-DQB1*0302 haplotype at clinical onset of type 1 insulin dependent diabetes before age of 10 but not at onset between age 10 and 40. Diabetologia. 1994;36:1155–62. doi: 10.1007/BF00401060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hagopian WA, Sanjeevi CB, Kockum I, et al. Glutamic decarboxylase, insulin-, and islet cell-antibodies and HLA typing to detect diabetes in a general population-based study of Swedish children. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:1505–11. doi: 10.1172/JCI117822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Genovese S, Bonfanti R, Bazzigaluppi E, Lampasona V, Benazzi E, Bosi E, Chiumello G, Bonifacio E. Association of IA-2 autoantibodies with HLA DR phenotypes in IDDM. Diabetologia. 1996;39:1223–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02658510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ludvigsson J, Samuelsson U, Beauforts C, et al. HLA-DR3 is associated with a more slowly progressive form of type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes. Diabetologia. 1986;29:207–10. doi: 10.1007/BF00454876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Veijola R, Knip M, Reijonen H, Vähäsalo P, Puukka R, Ilonen J. Effect of genetic risk load defined by HLA-DQB1 polymorphism on clinical characteristics of IDDM in children. Eur J Clin Invest. 1995;25:106–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1995.tb01534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Genovese S, Bonifacio E, McNally JM, Dean BM, Wagner R, Bosi E, Gale EA, Bottazzo GF. Distinct cytoplasmic islet cell antibodies with different risks for type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1992;35:385–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00401207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arslanian SA, Becker D, Rabin B, Atchison R, Eberhardt M, Cavender D, Dorman J, Drash AL. Correlates of insulin autoantibodies in newly diagnosed children with insulin-dependent diabetes before insulin therapy. Diabetes. 1985;34:926–30. doi: 10.2337/diab.34.9.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karjalainen J, Knip M, Mustonen A, Ilonen J, Åkerblom HK. Relation between insulin antibody and complement-fixing islet cell antibody at clinical diagnosis of IDDM. Diabetes. 1986;35:620–2. doi: 10.2337/diab.35.5.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vähäsalo P, Knip M, Karjalainen J, Tuomilehto-Wolf E, Lounamaa R, Åkerblom HK. the Childhood diabetes in Finland Study Group. Islet cell specific autoantibodies in children with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and their siblings at clinical manifestation of the disease. Eur J Endocrinol. 1996;134:689–95. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1350689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gorus FK, Goubert P, Semakula C, et al. IA-2 autoantibodies complement GAD65 autoantibodies in new-onset IDDM patients and help predict impending diabetes in their siblings. Diabetologia. 1997;40:95–99. doi: 10.1007/s001250050648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vandewalle CL, Falorni A, Lernmark A, et al. Associations of GAD65- and IA-2-autoantibodies with genetic risk markers in new-onset IDDM patients and their siblings. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1547–52. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.10.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yki-Järvinen H. MODY genes and mutations in hepatocyte nuclear factors. Lancet. 1997;349:516–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)80078-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knip M, Kulmala P, Petersen JS, Vähäsalo P, Karjalainen J, Dyrberg T, Åkerblom HK, the Childhood Diabetes in Finland Study Group Evolution of islet cell associated autoimmunity in preclinical IDDM. Diabetologia. 1995;38(Suppl. 1):A88. (Abstr.) [Google Scholar]