Abstract

Anti-cardiolipin autoantibodies (aCL) induce thrombosis and recurrent fetal death. These antibodies require a ‘cofactor’, identified as β2-glycoprotein I (β2-GPI), to bind phospholipids. We show here that aCL can bind β2-GPI in the absence of phospholipid. Binding of aCL to β2-GPI is dependent upon the β2-GPI being immobilized on an appropriate surface including cardiolipin, irradiated polystyrene and nitrocellulose membrane. This effect cannot be explained by increased antigen density of β2-GPI immobilized on these surfaces. Rather, conformational changes that occur following the interaction of β2-GPI with phospholipid render this protein antigenic to aCL. Liquid-phase β2-GPI was not antigenic for aCL. Thus, aCL cannot bind circulating β2-GPI. These findings may explain why patients with aCL can remain healthy for many years but then undergo episodes of thrombosis or fetal loss without changes in their circulating aCL profile, as the triggering event for these pathologies can be predicted to be one that renders β2-GPI antigenic for aCL.

Keywords: β2-glycoprotein I, anti-phospholipid, autoantibodies, antigen binding, autoimmunity, lupus

INTRODUCTION

Anti-cardiolipin autoantibodies (aCL) are part of the family of anti-phospholipid autoantibodies that can cause thrombosis and pregnancy losses [1–7]. The mechanism(s) by which these autoantibodies are pathogenic is undefined. It has been reported that aCL require a plasma protein ‘cofactor’ identified as β2-glycoprotein I (β2-GPI) to bind phospholipid [8–11]. There is uncertainty as to the true nature of the antigen for aCL, with some reports suggesting that aCL can bind to β2-GPI in the absence of phospholipid, whilst others are contradictory [8,12–14]. Matsuura et al. [15] provided a possible explanation by showing that exposure of polystyrene ELISA plates to γ-radiation results in incorporation of oxygen into the plate surface, causing an overall increase in the negative charge. This process, as well as UV-radiation of polystyrene, is used by manufacturers to improve the hydrophilicity and protein binding characteristics of ELISA plates. The surface of irradiated plates is postulated to mimic the surface of cardiolipin-coated plates and facilitate the direct binding of aCL to β2-GPI.

It is important to identify the true antigen of aCL for two reasons. First, aCL immunoassay data are inconsistent and a more accurate definition of the antigen for aCL should allow development of a more reliable clinical screening assay upon which more rational treatment decisions may be based. Second, in order to attain the ultimate goal of preventing aCL-mediated diseases the basic pathogenic mechanism of these autoantibodies must be better understood. In this study we investigated (i) whether aCL bind to phospholipid-free β2-GPI in various immunoassay systems, and (ii) the mechanism by which this binding occurs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Purification and biotinylation of β2-GPI

β2-glycoprotein I was purified as previously described [16] and the absence of phospholipid confirmed by testing for phosphate using a commercially available kit (Sigma, Sydney, Australia). β2-GPI preparations were demonstrated to be > 99.5% phosphate-free by weight.

Purified β2-GPI (5 mg) was dialysed against three changes of PBS pH 7.4, then incubated for 20 min at 4°C with 10 mm NaIO4. The oxidized β2-GPI was biotinylated by incubation overnight at 4°C with 9 mg biotin LC-hydrazide (Pierce, Rockford, IL) dissolved in 300 μl dimethyl sulphoxide. Free biotin was removed by repeated dialysis against PBS pH 7.4.

γ-radiation of ELISA plates

Polystyrene 96-well plates were exposed to varying levels of γ-radiation (25, 75 or 100 kGy) under an ambient oxygen atmosphere in a commercially operated plant using a cobalt source (Mallinckrodt Veterinary, Upper Huh, New Zealand).

Anti-cardiolipin antibody and β2-GPI antibody detection

Anti-cardiolipin antibodies and β2-GPI-reactive antibodies were detected by ELISAs as previously published [7,17].

Combined cardiolipin and β2-GPI ELISA

Wells of 96-well ELISA plates were coated with 50 μl of cardiolipin (Sigma; 50 μg/ml in ethanol) by evaporation overnight at 4°C. Simultaneously, other wells of the same ELISA plates were coated overnight at 4°C with 50 μl purified β2-GPI (10 μg in 0.1 m carbonate, pH 9.0). Plates were then washed three times with PBS pH 7.4. Cardiolipin–β2-GPI complexes were formed by incubating the required number of cardiolipin-coated wells with 50 μl/well of β2-GPI, 10 μg/ml in PBS, pH 7.4, for 1 h at room temperature. During this incubation, PBS pH 7.4 was added to the remaining cardiolipin-coated and β2-GPI-coated wells. All subsequent incubations were at room temperature. Plates were blocked by the addition of 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS pH 7.4 for 1 h. The blocking solution was discarded and plates were washed three times with PBS pH 7.4, and then samples diluted in blocking solution were incubated on the plates for 1 h. The plates were then washed three times with PBS pH 7.4, and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-human γ-chain antibody (Tago, Burlingame, CA), diluted 1:8500 in blocking solution, was added for a further 1 h. The plates were again washed three times with PBS pH 7.4, and the assay developed by addition of 1 mg/ml OPD (Sigma) in 0.1 m citrate buffer pH 5.5, containing 0.006% fresh H2O2. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 10% HCl, and optical density (OD) at 490 nm determined.

Determination of relative amounts of β2-GPI immobilized on polystyrene surfaces

A dilution series of biotinylated β2-GPI was prepared in 0.1 m carbonate buffer pH 9.0, and 50 μl incubated in the wells of the various 96-well polystyrene ELISA plates to be tested for 16 h at 4°C. The unbound protein was then removed by three washes with PBS–Tween 20 (PBS–T) pH 7.4, and plates were blocked by addition of 50 μl/well 5% non-fat milk powder (NFM) in PBS–T pH 7.4, for 1 h. Following three further washes with PBS–T pH 7.4, streptavidin-conjugated HRP (diluted 1:5000 in the blocking solution) was added and incubated on the plates for 30 min. Unbound protein was removed by washing three times with PBS–T pH 7.4, and the colourimetric assay developed by the addition of 1 mg/ml OPD (Sigma) in 0.1 m citrate buffer pH 5.5, containing 0.006% fresh H2O2. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 10% HCl and the OD determined.

That biotinylation did not affect binding of β2-GPI to ELISA plates was confirmed by comparing the binding of β2-GPI-reactive MoAbs to ELISA plates coated with equal amounts of both biotinylated and non-biotinylated β2-GPI. There was no statistical difference between the levels of binding (data not shown).

Cardiolipin liposome affinity chromatography

Cardiolipin antibodies were affinity-purified from patient serum using cardiolipin liposomes as previously described [11].

Electrophoresis and Western blotting using patient sera

Purified β2-GPI was electrophoresed on 8% non-reducing SDS–PAGE according to the method of Laemmli [18]. The protein was then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane which was cut into lanes and exposed either to individual patient serum, diluted in 5% NFM in PBS pH 7.4 containing 0.25% Tween 20 (PBS–H–T), or to an anti-β2-GPI MoAb, Jab-2 [16], for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were then washed in PBS–H–T pH 7.4, and HRP-conjugated anti-human (Tago) or anti-mouse (Sigma) γ-chain specific autoantibodies, diluted 1:500 or 1:1000, respectively, were incubated with the membranes for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were then washed with PBS–H–T pH 7.4, and developed using an enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (Amersham, Auckland, New Zealand) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The membranes were then exposed to x-ray film (Amersham), which was developed using a Kodak M35 X-OMAT automated developing system.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed by t-test or anova, as appropriate, using the Microsoft Excel (Version 5.0).

Patients

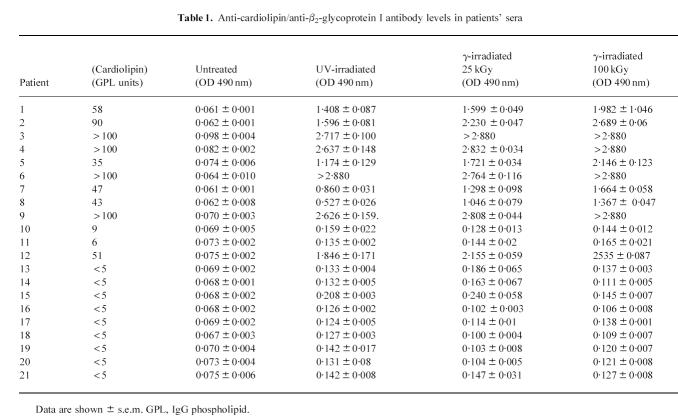

Ethical permission was obtained from the institutional ethics committee. Serum was obtained with informed consent from 11 women and one man with elevated levels of aCL > 5 IgG phospholipid (GPL) units (see Table 1). All fulfilled the criteria of anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome (aPLS) [19]. Serum was also obtained from nine normal volunteers.

Table 1.

Anti-cardiolipin/anti-β2-glycoprotein I antibody levels in patients' sera

RESULTS

The effect of γ-radiation of ELISA plates on assay levels of anti-β2-GPI autoantibodies in patients' sera

Serum samples from 12 patients with aCL and eight normal controls were tested for autoantibodies reactive with β2-GPI by ELISAs. The ELISAs employed polystyrene plates that were untreated or similar plates that had been exposed to UV-radiation by the manufacturer as well as plates that had been exposed to 25, 75 or 100 kGy γ-radiation (Table 1). None of the tested sera contained autoantibodies reactive with β2- GPI immobilized on untreated polystyrene ELISA plates. In contrast, 10 of the 12 aCL+ sera contained autoantibodies reactive with β2-GPI when this protein had been immobilized on the surface of commercially available UV-irradiated (Maxisorp, Nunc, Auckland, New Zealand) or γ-irradiated polystyrene ELISA plates, irrespective of the radiation dose (Table 1). Sera from the remaining two aCL+ patients (nos 10 and 11) had no anti-β2-GPI reactivity (Table 1).

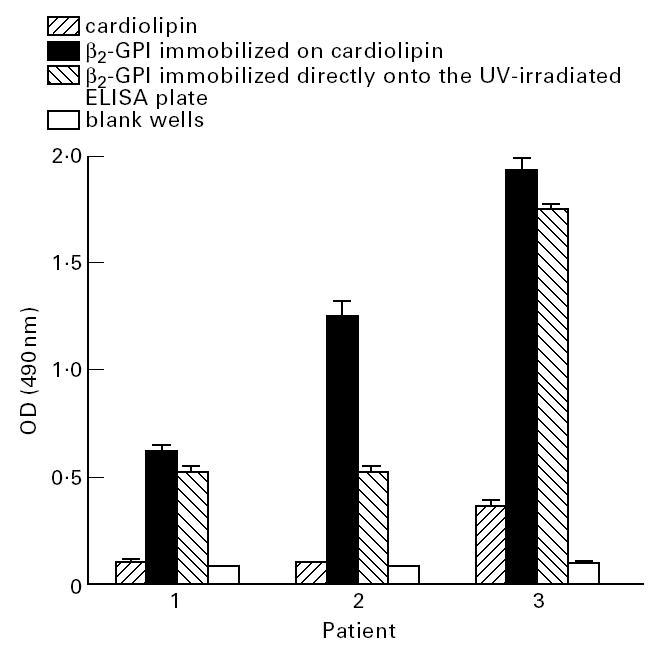

Binding characteristics of affinity-purified β2-GPI autoantibodies

Anti-cardiolipin antibodies were purified from the sera of three patients by cardiolipin liposome affinity and then assessed for their ability to bind to cardiolipin, cardiolipin–β2-GPI complexes or β2-GPI alone. The affinity-purified aCL bound to both cardiolipin–β2-GPI complexes and β2-GPI (immobilized on UV-irradiated polystyrene) alone, but not to cardiolipin in the absence of β2-GPI (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Anti-cardiolipin autoantibodies were affinity-purified from patient serum by cardiolipin liposome affinity chromatography and assessed for their ability to bind to cardiolipin, β2-glycoprotein I (β2-GPI) immobilized on cardiolipin, β2-GPI immobilized directly onto the UV-irradiated ELISA plate, or blank wells. All samples were assayed in quadruplicate on at least two separate occasions. Bars represent standard errors.

Quantification of binding of β2-GPI to different microtitre plates

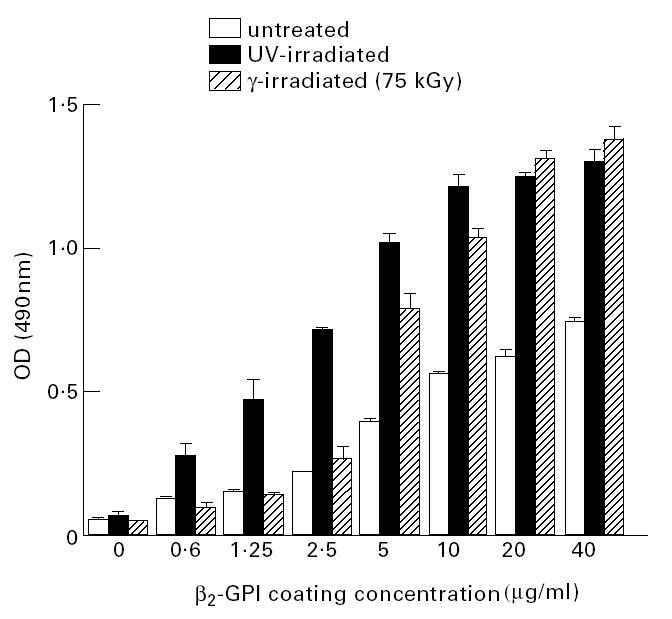

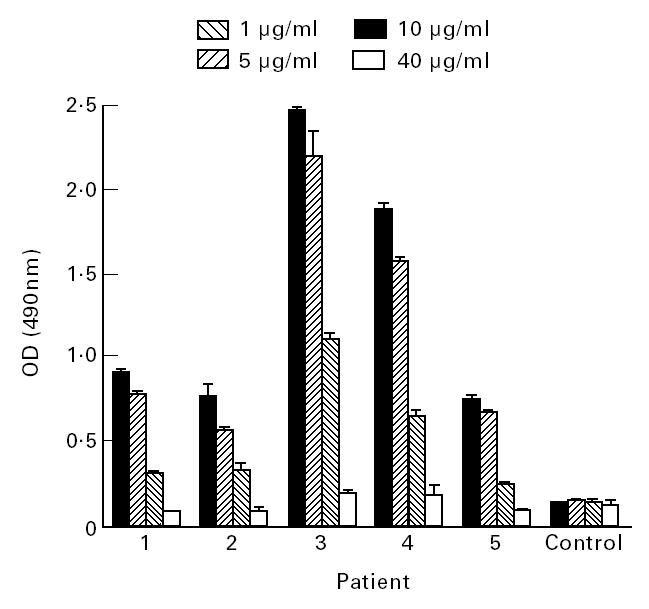

To investigate why aCL bound to β2-GPI immobilized on irradiated but not untreated polystyrene ELISA plates, the relative amounts of β2-GPI immobilized on untreated and UV- or γ-irradiated polystyrene ELISA plates were compared using biotinylated β2-GPI (Fig. 2). This analysis demonstrated significantly more β2-GPI was immobilized on the UV-irradiated polystyrene than on the untreated polystyrene at all coating concentrations tested (Fig. 2). However, of particular importance to the remainder of this study was the observation that, at a β2-GPI coating concentration of 40 μg/ml, significantly more β2-GPI was immobilized on untreated polystyrene plates than at a coating concentration of 1.25 μg/ml for UV-irradiated polystyrene ELISA plates (P < 0.01; t-test) (Fig. 3). The level of autoantibody binding to β2-GPI immobilized on UV-irradiated polystyrene ELISA plates at coating concentrations of 10, 5 or 1 μg/ml was then compared with the autoantibody binding to β2-GPI immobilized on untreated plates with a coating concentration of 40 μg/ml (Fig. 3). For all sera tested, there was significantly more autoantibody binding to β2-GPI (1 μg/ml) immobilized on the UV-irradiated plates than to β2-GPI (40 μg/ml) immobilized on untreated polystyrene ELISA plates (P < 0.01, patient 2; P < 0.0001, patients 1, 3 and 5; t-test) (Fig. 3). Binding of autoantibodies to β2-GPI immobilized on untreated plates remained at background levels (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

The amount of β2-glycoprotein I (β2-GPI) immobilized on untreated, UV-irradiated, or γ-irradiated (75 kGy) polystyrene ELISA plates was compared by coating plates with increasing concentrations of biotinylated β2-GPI for 16 h at 4°C followed by detection employing horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated streptavidin. At all coating concentrations tested, the amount of β2-GPI immobilized on UV-irradiated polystyrene plates was greater than that on untreated polystyrene plates. Binding of β2-GPI to UV-irradiated polystyrene plates was saturated using a coating concentration of 10 mg/ml. Use of coating concentrations of 20 or 40 μg/ml did not cause significantly more β2-GPI to bind to the UV-irradiated plates (P = 0.21, anova). The binding of β2-GPI to untreated polystyrene plates was not saturated at any coating concentration tested. Of relevance to subsequent work, significantly (P = 0.0029) more β2-GPI was immobilized on untreated plates coated at 40 mg/ml than on UV-irradiated polystyrene plates using a coating concentration of 1.25 μg/ml. All samples were assayed in quadruplicate on at least two separate occasions. Bars represent standard errors.

Fig. 3.

The binding of autoantibodies from patient serum, or control normal human serum, to β2-glycoprotein I (β2-GPI) immobilized at different concentrations (1, 5 or 10 μg/ml) on UV-irradiated, or (40 μg/ml) on untreated, polystyrene plates was examined by ELISA. For all patients, there was a significantly higher level of autoantibody binding to β2-GPI immobilized on UV-irradiated plates, regardless of the coating concentration used, than to untreated plates coated with 40 μg/ml β2-GPI. All samples were assayed in quadruplicate on at least two separate occasions. Bars represent standard errors.

The antigenicity of liquid-phase β2-GPI

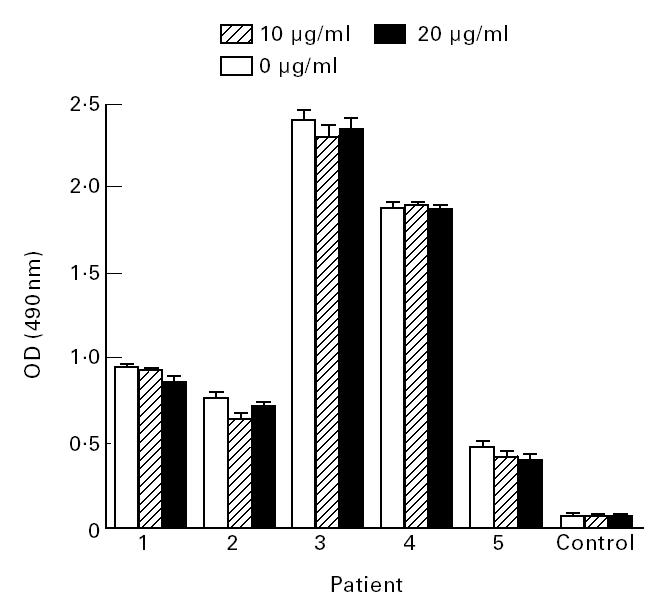

Liquid phase β2-GPI did not significantly inhibit autoantibody binding to β2-GPI immobilized on UV-irradiated polystyrene even when the concentration of liquid-phase β2-GPI exceeded the concentration used when immobilizing on the plates, demonstrating that liquid-phase β2-GPI is not antigenic for aCL (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The ability of liquid-phase β2-glycoprotein I (β2-GPI) to inhibit the binding of autoantibodies from patient serum to β2-GPI immobilized on UV-irradiated polystyrene plates was examined by ELISA. Normal human serum was also included in the assays as a control. There was no inhibition for any at either 10 μg/ml or 20 μg/ml inhibitory β2-GPI (P > 0.05, t-test) compared with the samples containing no inhibitory β2-GPI. These assays were conducted in quadruplicate on at least two separate occasions. Bars represent standard errors.

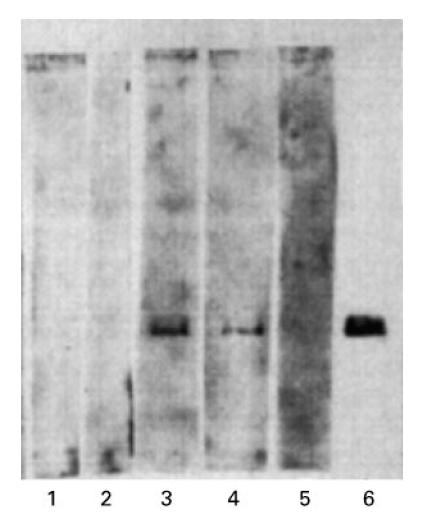

Detection of anti-β2-GPI autoantibodies by Western blotting

Western blots of β2-GPI were probed with sera of four patients with aCL. Autoantibodies from two patients' sera (nos 1 and 3), but not two further patients (nos 2 and 5) or control normal sera, reacted with β2-GPI (Fig. 5). The strongest reaction was produced by autoantibodies from patient 1, who had moderate levels of aCL and β2-GPI autoantibodies by ELISA (Fig. 5 and Table 1). In contrast, patients 2 and 3 had considerably higher levels of aCL–β2-GPI autoantibodies by ELISA (Table 1) but produced no or weak reactivity with β2-GPI, respectively, by Western blot.

Fig. 5.

β2-glycoprotein I (β2-GPI) was electrophoresed on an 8% SDS–PAGE gel, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and probed with anti-cardiolipin autoantibody (aCL)-containing patient sera (lane 1, patient 5; lane 2, patient 2; lane 3, patient 1; lane 4, patient 3), normal human serum (lane 5) or the anti-β2-GPI MoAb Jab-2 (lane 6). aCL from two patients (1 and 3) reacted with the immobilized β2-GPI. In contrast, the ELISA reactivity of patients' 2 and 3 sera with β2-GPI was higher than that of patient 1, indicating that the reactivity by Western blotting was not proportional to the level of anti-β2-GPI reactivity by ELISA.

DISCUSSION

Recently, Horkko et al. [20] have shown the recommended procedure for coating cardiolipin on ELISA plates (evaporation from an ethanolic solution overnight) leads to the oxidation of the cardiolipin [20]. Exposure of polystyrene to γ- or UV-radiation results in incorporation of oxygen into the surface as C-0 and C = O [21]. Thus, both cardiolipin-coated and irradiated polystyrene plates have oxidized, negatively charged surfaces. It is postulated that the increased negative charge on the surface of irradiated polystyrene plates mimics the negative charge of a cardiolipin-coated ELISA plate, and that it is this increased negative charge that renders β2-GPI antigenic for aCL. Untreated polystyrene ELISA plates do not have such a charged surface. Our data confirm that β2-GPI immobilized on untreated polystyrene is not antigenic for aCL, but β2-GPI immobilized on irradiated polystyrene is antigenic for aCL. In order to confirm that autoantibodies binding to β2-GPI immobilized on irradiated polystyrene are indeed aCL, we have shown that affinity-purified aCL also react with β2-GPI immobilized on either cardiolipin-coated or irradiated polystyrene plates, but do not react with β2-GPI immobilized on untreated polystyrene plates. Further, these affinity-purified autoantibodies did not bind directly to cardiolipin in the absence of β2-GPI. These data confirm that so-called anti-cardiolipin autoantibodies in fact react directly with β2-GPI, but only when β2-GPI is immobilized on an appropriate surface.

There are two possible explanations why β2-GPI immobilized on irradiated but not untreated polystyrene plates is antigenic for aCL. The first is that insufficient β2-GPI is bound to the untreated plate to facilitate aCL binding and irradiating the polystyrene increases the amount of β2-GPI immobilized on the plate surface. The second is that, upon binding to irradiated polystyrene (or cardiolipin-coated polystyrene), β2-GPI undergoes a conformational change essential to render it antigenic to aCL. We have presented three separate lines of evidence in support of the latter explanation. First, aCL bound β2-GPI immobilized on UV-irradiated polystyrene when coating concentrations of β2-GPI as low as 1 μg/ml were used. In contrast, patient autoantibodies did not bind to β2-GPI immobilized on untreated polystyrene plates, even when coating concentrations of β2-GPI were as high as 40 μg/ml. At these respective coating concentrations, significantly more β2-GPI was immobilized on untreated plates than on UV-irradiated plates. Thus, although we found less β2-GPI was immobilized on untreated than on irradiated at any given coating concentration, this reduced antigen density does not explain why aCL did not react with β2-GPI immobilized on untreated polystyrene.

Second, we and others [15,22] have shown that liquid-phase β2-GPI is not antigenic for aCL and cannot inhibit the binding of aCL to β2-GPI immobilized on irradiated polystyrene. Liquid-phase β2-GPI has not undergone the putative conformational change induced by interaction with negative surfaces and therefore would not be expected to inhibit binding of aCL to immobilized (conformationally altered) β2-GPI.

Third, we have demonstrated that aCL from some, but not all, patients with aCL that bind β2-GPI immobilized on irradiated polystyrene can also bind to β2-GPI immobilized on negatively charged nitrocellulose membrane. If, as suggested by others [22,23], negative surfaces simply increase the antigen density of β2-GPI to allow binding of low-affinity aCL, it would be anticipated that all aCL reactive with β2-GPI by ELISA would also be reactive with β2-GPI by Western blot. Our data show this is not the case. Our results are instead consistent with the suggestion that a conformational change occurs in β2-GPI once it interacts with a negative surface, and that this change may be subtly different depending upon the exact nature of the surface. This is consistent with the demonstration, by circular dichroism, that β2-GPI undergoes a conformational. change upon interaction with phospholipid [24].

From the conclusion that aCL react only with conformationally altered β2-GPI, we can surmise that these antibodies react with only one or a limited number of epitopes on (conformationally altered) β2-GPI. Further, that aCL bind to β2-GPI only when this protein is bound to an appropriate surface may explain why patients with these autoantibodies have episodes of thrombosis interspersed with long periods of good health. As aCL cannot bind liquid-phase β2-GPI, circulating β2-GPI will not be bound by these autoantibodies. Rather, β2-GPI must be immobilized on a suitable surface before aCL can bind. The most likely surface of physiological relevance is negatively charged phospholipid, particularly phosphatidyl serine. However, this phospholipid is not a normal component of the accessible outer leaflet of the membrane of resting cells. Upon cellular activation or apoptosis, negatively charged phospholipid ‘flip flops’ from the interior to exterior leaflet of the membrane where it would be able of immobilizing and conformationally altering β2-GPI [25]. Thus, a triggering event, such as cellular activation or damage, which is independent of aCL, must occur prior to pathogenesis in aCL+ individuals.

In the course of this study, we identified two patients with low levels of serum aCL but no anti-β2-GPI autoantibodies regardless of the assay conditions. Both patients had clinical features of aPLS (one had 12 first trimester losses and the other had systemic lupus erythematosus and four perinatal deaths) and neither had any other identifiable cause of pregnancy failures. Thus, these women were considered to have aPLS, but our results using the β2-GPI ELISA suggest that the low-level aCL were false-positives and that neither woman had aPLS. This is clinically important, as treatment, which could include long-term anticoagulation or high-dose corticosteroids, could be administered on the basis of a (false) positive aCL test. A combination of ELISAs to detect autoantibodies reactive with β2-GPI (immobilized on irradiated polystyrene plates) and traditional aCL ELISA may prove to be a useful tool for discriminating between true- and false-positive aCL assay results.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Mrs Fay Adams for her valuable assistance in preparing the graphics for this publication. This research is supported by grants from the Health Research Council of New Zealand, The Auckland Medical Research Foundation and the Wellcome Trust.

References

- 1.Harris EN, Gharavi AE, Boey ML, et al. Anticardiolipin antibodies: detection by radioimmunoassay and association with thrombosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lancet. 1983;ii:1211–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)91267-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asherson RA, Mercey D, Phillips G, et al. Recurrent stroke and multi-infarct dementia in systemic lupus erythematosus: association with antiphospholipid antibodies. Ann Rheum Dis. 1987;46:605–11. doi: 10.1136/ard.46.8.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Branch DW, Andres R, Digre KB, et al. The association of antiphospholipid antibodies with severe pre-eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73:541–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kushner MJ. Prospective study of anticardiolipin antibodies in stroke. Stroke. 1990;21:295–8. doi: 10.1161/01.str.21.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Long AA, Ginsberg JS, Brill-Edwards P, et al. The relationship of antiphospholipid antibodies to thromboembolic disease in systemic lupus erythematosus: a cross-sectional study. Thromb Haem. 1991;66:520–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birdsall MA, Pattison NS, Chamley LW. Antiphospholipid antibodies and adverse pregnancy outcome. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;32:328–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.1992.tb02844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pattison NS, Chamley LW, Liggins GC, et al. Antiphospholipid antibodies in pregnancy: prevalence and clinical associations. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;100:909–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1993.tb15105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galli M, Comfurius P, Maassen C, et al. Anticardiolipin antibodies (ACA) directed not to cardiolipin but to a plasma protein cofactor. Lancet. 1990;335:1544–7. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91374-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McNeil HP, Simpson RJ, Chesterman CN, Krilis SA. Antiphospholipid antibodies are directed against a complex antigen that includes a lipid-binding inhibitor of coagulation: β2-glycoprotein I (apolipoprotein H) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4120–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.11.4120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsuura E, lgarashi Y, Fujimoto M, et al. Anticardiolipin cofactor(s) and differential diagnosis of autoimmune disease. Lancet. 1990;336:177–8. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chamley LW, McKay EJ, Pattison NS. Cofactor dependent and cofactor independent anticardiolipin antibodies. Thromb Res. 1991;61:291–9. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(91)90106-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones JV, James H, Tan MH, Mansour M. Antiphospholipid antibodies require β2-glycoprotein I (apolipoprotein H) as cofactor. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:1397–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pierangeli SS, Harris EN, Davis SA, DeLorenzo G. β2-glycoprotein I (β2-GPI) enhances cardiolipin binding activity but is not the antigen for antiphospholipid antibodies. Br J Haem. 1992;82:565–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1992.tb06468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang M-X, Kandiah DA, Ichikawa K, et al. Epitope specificity of monoclonal anti-β2-GPI autoantibodies derived from patients with the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. J Immunol. 1995;155:1629–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuura E, Igarashi Y, Yasuda T, et al. Anticardiolipin antibodies recognise β2-glycoprotein I structure altered by interacting with an oxygen modified solid phase surface. J Exp Med. 1994;179:457–62. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chamley LW, Allen JL, Johnson PM. Synthesis of β2-glycoprotein I by the human placenta. Placenta. 1997;18:403–10. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(97)80040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stern C, Chamley LW, Hale L, et al. Antibodies to β2-glycoprotein I are significantly associated with in-vitro-fertilisation implantation failure as well as recurrent miscarriage: results of a prospective prevalence study. Fertility and Sterility. 1988;70:938–44. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(98)00312-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–5. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris EN. Syndrome of the black swan. Br J Rheumatol. 1981;26:324–6. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/26.5.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horkko S, Miller E, Dudl E, et al. Antiphospholipid antibodies are directed against epitopes of oxidised phospholipids. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:815–25. doi: 10.1172/JCI118854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Onyiriruka EC, Hersh LS, Hertl W. Surface modification of polystyrene by gamma radiation. Applied Spectroscopy. 1990;44:808–11. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roubey RAS, Eisenberg RA, Harper MF, Winfield JB. ‘Anticardiolipin’ autoantibodies recognise β2-glycoprotein I in the absence of phospholipid. J Immunol. 1995;154:954–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tincani A, Spatola L, Prati E, et al. The anti-β2-glycoprotein I activity in human antiphospholipid syndrome sera is due to monoreactive low-affinity autoantibodies directed to epitopes located on native β2-glycoprotein I and preserved during species' evolution. J Immunol. 1996;157:5732–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borchman D, Harris EN, Pierangeli SS, Lamba OP. Interactions and molecular structure of cardiolipin and β2-glycoprotein I (β2-GPI) Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;102:373–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb03792.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gerrard JM, Friesen LL. Platelets. In: poller L, editor. Recent advances in blood coagulation. Vol. 4. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1985. pp. 139–68. [Google Scholar]