Abstract

The relation of serum cytokine levels and outcome of chemotherapy was evaluated in 15 patients with cystic echinococcosis. Serum IL-4, IL-10 and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) concentrations were determined by ELISA before and after a 3-month course of albendazole treatment: at least one serum sample per patient from 13 patients (87%) contained measurable amounts of IL-4; samples from five patients (33%) measurable amounts of IL-10 and samples from only two patients (13%) measurable amounts of IFN-γ. Clinical assessment at 1 year after the end of therapy showed that 11 of the 15 patients had responded clinically. Seven of these patients had lower IL-4 serum concentrations, two had unchanged and two undetectable amounts (pre- versus post-therapy, n = 11, P = 0.008). Conversely, of the patients who did not respond, three had higher and one patient unchanged serum IL-4 concentrations. Serum IL-10 levels also decreased in all patients who responded (3/5) and increased in all patients who did not (2/5). No association was found between cytokine concentrations and cyst characteristics or antibody levels. Overall these data suggest that serum IL-4 detection may be useful in the follow up of patients with cystic echinococcosis.

Keywords: cystic echinococcosis, serum Th1/Th2 cytokines, follow up, chemotherapy

INTRODUCTION

Cystic echinococcosis (CE) is a severe parasitic disease caused by the cestode Echinococcus granulosus. In humans the larval forms develop into large cysts, especially in the liver, lung and brain. Echinococcus granulosus in humans triggers a humoral and cellular response characterized by elevated serum antibodies and by concurrent intervention of Th1 and Th2 cytokines [1]. The variability and severity of the clinical expression of the disease probably also reflect the variety of human immunological responses to the parasite. Therapy of CE is primarily surgical, even though pharmacological treatment with benzimidazole carbamates is nowadays an effective alternative [2–6]. Clinical evaluation of the outcome of the disease is difficult and relies on combined imaging methods and serological techniques. Because specific antibodies persist in patients' sera for several years after recovery, a long-term clinical and serological follow up is required to evaluate the success or failure of therapy. New and interesting research subjects in the immunosurveillance of CE include cytokines possibly associated with the outcome of the disease. In recent studies we observed the in vitro production of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), IL-4, IL-5, IL-6 and IL-10 by peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from patients with CE and suggested that Th1 cell activation (IFN-γ production) might be associated with protective immunity and Th2 cell activation with susceptibility to the disease (IL-4 and IL-10 production) [1,7,8]. Although two studies have reported the presence of cytokines in sera from surgically treated CE patients, neither of them evaluated the association between cytokines and the clinical outcome of the disease [9,10]. In particular, Torcal et al. reported a close relationship of IL-1, IL-2 and IL-4 with the number, characteristics and location of cysts within the liver; Touil-Boukuffa et al. postulated that after surgical removal of hydatid cysts, measurement of serum cytokine levels might allow early detection of relapse [9,10].

Continuing our research programme into the identification of immunological markers indicating the effectiveness of pharmacological treatment, in the present study we have expanded our initial in vitro observations monitoring serum IL-4, IL-10 and IFN-γ concentrations in 15 pharmacologically treated CE patients to evaluate in vivo the association of cytokine production with the outcome of disease. We also wanted to assess a possible relationship of serum cytokines with immunoglobulin expression and cyst characteristics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Serum samples

Serum samples were obtained from 15 CE patients (10 with cysts in the liver and five with cysts in multiple sites) and from 10 sex- and age-matched healthy donors. Diagnosis was assessed on the basis of imaging techniques (ultrasonographic scanning or nuclear magnetic resonance or both), serological assays, surgery or ex adiuvantibus after medical treatment. Patients' sera were obtained before and at the end of pharmacological treatment with a 3-month cycle of albendazole (10–12 mg/kg per day), as reported by the Bulletin of the WHO Working Group [11]. Some patients were also tested 1 month after the beginning or 1 year after the end of therapy. The effectiveness of therapy was evaluated by objective criteria mainly based on imaging techniques. The long-term outcome of therapy was assessed by the presence or the lack of relapse 1 year after the end of pharmacological treatment. None of the patients studied had a history of atopic manifestations or peripheral blood eosinophilia or other infectious diseases. All procedures were approved by the local Ethical Committee and all subjects gave their informed consent to the study. Fifteen sera were collected before chemotherapy, 3 at 1 month after the beginning of chemotherapy and 18 after the end of therapy. Sera were aliquoted, stored at −80°C and thawed only once. The cysts were classified sonographically into seven morphological types as described by Caremani et al. [12]. In brief, type I cysts are simple cysts (overall echo-free without echoes or internal structures, Ia; echo-free but with fine and suspended echoes, Ib) and type II are multiple cysts (multiple contiguous, with or without thin echoes, IIa; with septations, appearing as a rosette, honeycomb, or wheel-like pattern, IIb).

Cytokine assays

IL-4, IL-10 and IFN-γ concentrations in patients' sera were determined by ELISA by the use of human IL-4 HS (intra-assay precision: CV (%) = 6.6; inter-assay precision: CV (%) = 7.9), human IL-10 (intra-assay precision: CV (%) = 3.7; inter-assay precision: CV (%) = 6.8) and IFN-γ (intra-assay precision: CV (%) = 3.8; inter assay precision: CV (%) = 6.1) (Quantikine; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) as recommended by the manufacturer. The ranges of ELISA kits were 0.25–16 pg/ml for IL-4, 7.8–500 pg/ml for IL-10, and 15.6–1000 pg/ml for IFN-γ. Each serum was tested in triplicate.

Serological assays

Patients sera were tested with ELISA for immunoglobulin isotypes and E. granulosus antigens as described by Riganò et al. [7]. Optical densities (OD) at 492 nm were considered positive when higher than 0.3 for IgE, 0.6 for IgG, 0.1 for IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, and 0.2 for IgG4 (mean + 2 s.d. of the absorbance readings of the uninfected controls). Immunoblotting (IB) followed the procedure previously described by Siracusano et al. [13] after SDS–PAGE in a 7.5–20% gradient gel and in non-reducing conditions. To assess indirect evidence of IgE-dependent humoral immune response we used a non-quantitative histamine release test (HRT) [14].

Statistical analysis

Results of cytokine production are expressed as median value. Wilcoxon signed rank test for non-parametric data was used to compare cytokine production. Differences with a confidence interval (CI) of ≥ 95% were considered statistically significant (P < 0.05).

RESULTS

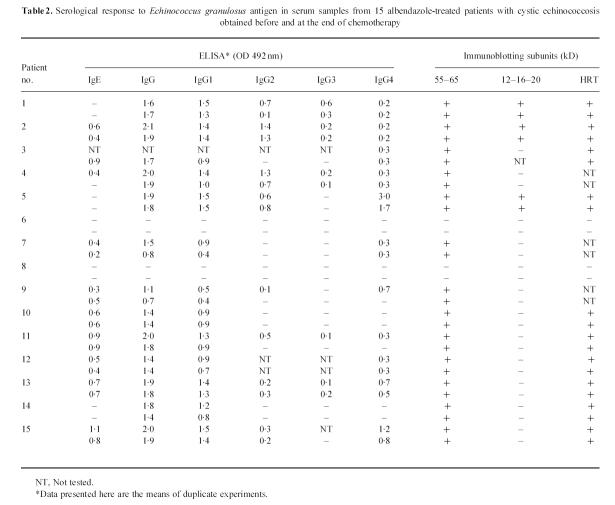

At least one serum sample from most of the pharmacologically treated patients with CE (13/15, 87%) contained measurable amounts of IL-4 but only few patients' samples (5/15, 33%) contained IL-10. Even fewer patients' samples (2/15, 13%) showed measurable IFN-γ (Table 1). Sera from the 10 healthy donors were negative for circulating cytokines in all tests.

Table 1.

Cytokine detection in sera from 15 albendazole-treated patients with cystic echinococcosis

Clinical and imaging assessment at 1 year after the end of albendazole therapy showed that 11 of the 15 patients had responded clinically. Seven of these patients (patients 1–4, 9–11) had lower IL-4 serum concentrations, two (patients 5 and 7) had unchanged and two (patients 6 and 8) had undetectable amounts. In patients 1, 2 and 4 serum IL-4 concentrations had already decreased 1 month after the beginning of therapy. In patient 3 the decrease seen at the end of the 3-month course of therapy remained unchanged at 1 year. Of the 15 patients, four did not respond clinically, three of these patients had higher and one patient unchanged serum IL-4 concentrations. In patients 13 and 14 1 year after therapy, IL-4 serum concentrations increased further.

Serum IL-10 levels also decreased in the three patients who had responded clinically to therapy at 1 year but increased in the two patients who did not.

Patients who had responded clinically to therapy at 1 year had significantly higher median IL-4 concentrations before therapy (0.6 pg/ml; 95% confidence interval: 0.0–1.2) than after therapy (0.0 pg/ml; 95% confidence interval: 0.0–0.2) and the difference was statistically significant (n = 11, P = 0.008). Patients who did not respond had lower concentrations before therapy (0.0 pg/ml; 95% confidence interval: 0.0–0.4) than after therapy (1.0 pg/ml; 95% confidence interval: 0.5–1.5), but the median value did not differ significantly. Post-therapy IL-4 concentrations differed significantly in the two groups (0.24 pg/ml versus 1.05 pg/ml; P = 0.03). Patients who had responded at 1 year had higher pretherapy serum IL-4 concentrations than patients who did not respond (1.12 pg/ml versus 0.20 pg/ml).

Diagnostic imaging assessment showed that most patients who had responded clinically at 1 year (8/11) had type I cysts (maximum diameter 0.5–10 cm) and few patients (3/11) had type II cysts (maximum diameter 3–16 cm) according to the morphological classification of Caremani et al. [12]. In contrast, the four patients who did not respond to therapy at 1 year all had type II cysts (maximum diameter 13–18 cm) (Table 1).

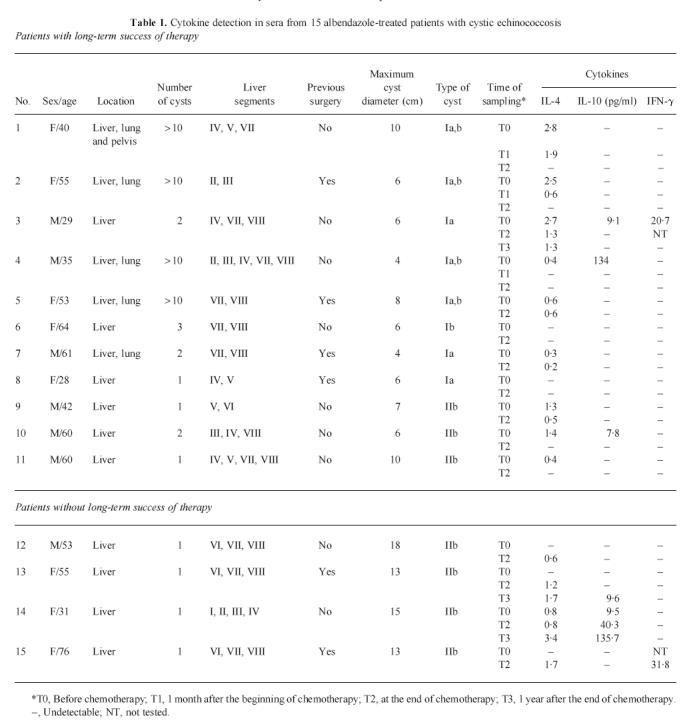

ELISA and IB showed that only 2/15 CE patients' sera contained no detectable specific antibodies against E. granulosus antigens. In immunoglobulin isotyping by ELISA, 9/13 patients (69%) were IgE- and IgG4-positive, two (15%) were positive for IgG4 alone (but HRT-positive), one patient (6%) was positive for IgE alone and two patients (15%) were negative for both isotypes (Table 2). As expected, ELISA values showed that the humoral response remained substantially unchanged at the end of therapy. All antibody-positive patients recognized in IB the 55- and 65-kD subunits of antigen 5 and three patients also recognized the 12-, 16- and 20-kD subunits of antigen B. The two seronegative patients (patients 6 and 8) were also the only two IL-4-negative patients.

Table 2.

Serological response to Echinococcus granulosus antigen in serum samples from 15 albendazole-treated patients with cystic echinococcosis obtained before and at the end of chemotherapy

DISCUSSION

One of the most immediate needs in the post-surgical or post-pharmacological treatment immunosurveillance of CE patients is to identify markers indicating the effectiveness of treatment. The frequent relapse of disease (25%) after an initial therapeutic success [2] is nowadays a serious problem in the pharmacological treatment of CE.

The results of our preliminary in vitro study show a clear association between IL-4/IL-10 cytokine levels in patients with CE and outcome of albendazole therapy. Most of our patients' sera (87%) contained IL-4; comparatively few (33%) contained IL-10, whereas fewer (13%) contained IFN-γ. Despite imaging evidence of degenerative changes in the cyst at the end of a 3-month course of chemotherapy, the significant decrease in serum IL-4 concentrations after therapy in patients who responded at 1 year and the increased concentrations in those who did not suggest that serum cytokine detection will be useful in the clinical follow up of patients with CE.

In a previous in vitro study we showed higher Th2 cytokine (IL-4 and IL-10) concentrations in patients who did not respond to chemotherapy but higher Th1 cytokine (IFN-γ) concentrations in patients who did respond [7]. In this in vivo study we report similar results for circulating IL-4 and IL-10. Interestingly, the increased serum IL-4/IL-10 in patients with active disease, apparently relatively resistant to chemotherapy, emphasizes in vivo a predominantly Th2 response in patients with chronic CE. The low percentage of patients (13%) whose sera were positive for circulating IFN-γ in this study prevents us from confirming the association of Th1 cell activation with the outcome of chemotherapy. Overall these questions await definitive answers from studies using more sensitive reagents in a larger number of patients.

As an alternative to surgery, pharmacological treatment with benzoimidazole carbamates is effective mainly in patients whose cysts are still young and active (types I and II). The drug penetrates the cyst and kills protoscoleces, brood capsules and germinal membrane [15]. During pharmacological treatment the host immune system may be exposed to varying antigens or antigen concentrations. This could partly explain why cytokine expression varied widely in our patients. These cytokine differences may also reflect the individual's expanding peripheral repertoire during chronic infections. Host genetic factors could also be involved.

The clinical findings in our patients agree with the frequent failure of therapy in patients with large, type II cysts. Accordingly, we found that chemotherapy succeeded in all patients with type I cysts and in the three patients with the smallest, type II cysts (diameter 3–10 cm). Why most patients with large cysts in whom therapy failed were IL-4-positive only after chemotherapy remains unclear.

In their recent study of patients with CE in the liver Torcal et al. detected IL-1, IL-2, IL-4 and tumour necrosis factor (TNF) serum levels before surgery, with high levels of IL-4 in patients and in healthy donors [9]. The far lower IL-4 concentrations present in our patient sera and the apparent absence of this cytokine in sera from healthy donors could therefore reflect differences in experimental conditions or in geographical/clinical characteristics of patients and controls. Torcal et al. also found higher IL-4 serum levels in patients with cysts in central and paramedian sites in the liver than in patients with peripheral localizations, whereas we observed no association between IL-4 concentrations and cyst localization in the liver. The same investigators reported a significant correlation between the level of total IgG and IL-4. Although again we failed to observe this correlation, neither of our two seronegative patients had detectable circulating IL-4 concentrations. As expected, our IL-4-positive patients were positive for IgE, IgG4, HRT, or for all three. Determining circulating IFN, TNF-α and IL-6 in CE patients before and after surgery, Touil-Boukoffa et al. [10] observed a rapid decrease in serum cytokine levels and in seroreactivity to parasitic antigen after surgery. We also found that in patients with long-term success of therapy circulating IL-4 decreased rapidly after chemotherapy, probably a drug-induced effect. Yet 1 year after the 3-month course of therapy serum antibodies against E. granulosus antigens remained high (data not shown).

If our in vivo findings are confirmed and more sensitive methods are found for measuring serum cytokine levels, new and interesting perspectives will be opened in the monitoring and therapy of CE. A rapid test for serum cytokine detection could identify patients at risk of relapse; these patients could be monitored more closely and may be candidates for immunotherapy with recombinant cytokines. Until more is known about the role of in vivo cytokines in the clinical outcome of disease, such approaches need to be pursued with extreme caution.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr D. Celestino for providing the HRT results.

References

- 1.Riganò R, Profumo E, Di Felice G, et al. In vitro production of cytokines by peripheral blood mononuclear cells from hydatid patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;99:433–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb05569.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teggi A, Lastilla MG, De Rosa F. Therapy of human hydatid disease with Mebendazole and Albendazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1679–84. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.8.1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horton RJ. Chemotherapy of Echinococcus infection in man with albendazole. Trans R Soc Med Hyg. 1989;83:97–102. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(89)90724-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Todorov T, Vutova K, Mechkov G, et al. Evaluation of response to chemotherapy of human cystic echinococcosis. Br J Radiol. 1990;63:523–31. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-63-751-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wen H, New RRC, Craig PS. Diagnosis and treatment of human hydatidosis. Br J Clin Pharm. 1993;35:565–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1993.tb04182.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pawloski Z, Dar FK, Eckert J, Kern P. Report of WHO Informal Group Meeting October 19 1994. Geneva: WHO; 1994. Guidelines for treatment of cystic and alveolar Echinococcosis in human. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riganò R, Profumo E, Ioppolo S, et al. Immunological markers indicating the effectiveness of pharmacological treatment in human hydatid disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;102:281–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb03778.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riganò R, Profumo E, Teggi A, et al. Production of IL-5 and IL-6 by peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) from patients with Echinococcus granulosus infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;105:456–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-796.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Torcal J, Navarro-Zorraquino M, Lozano R, et al. Immune response and in vivo production of cytokines in patients with liver hydatidosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;106:317–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-843.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Touil-Boukoffa C, Sanceau J, Tayebi B, et al. Relationship among circulating interferon, tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-6 and serologic reaction against parasitic antigen in human hydatidosis. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1997;17:211–7. doi: 10.1089/jir.1997.17.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO Informal Working Group on Echinococcosis. Guidelines for treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. Bull World Health Org. 1996;74:231–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caremani M, Benci A, Maestrini R, et al. Abdominal cystic hydatid disease (CHD): classification of sonographic appearance and response to treatment. J Clin Ultrasound. 1996;24:491–500. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0096(199611/12)24:9<491::AID-JCU1>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siracusano A, Ioppolo S, Notargiacomo S, et al. Detection of antibodies against Echinococcus granulosus major antigens and their subunits by immunoblotting. Transr Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1991;85:239–43. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(91)90039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aceti A, Celestino D, Teggi A, et al. Histamine release test in the diagnosis of human hydatidosis. Clin Exp Allergy. 1989;19:335–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1989.tb02392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chinnery JB, Morris DL. Effect of albendazole sulphoxide on viability of hydatid protoscoleces in vitro. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1986;80:815–7. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(86)90392-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]