Abstract

We analysed the spontaneous and cytokine-stimulated production and expression in vitro of IL-8, GROα, MCP-1, RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, by subchondral bone marrow stromal cells (BMSC) isolated from RA, OA, post-traumatic (PT) patients and normal donors (ND). BMSC were cultured in vitro in the presence or absence of IL-1β and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and assessed for chemokine production, expression and immunolocalization. BMSC from different sources constitutively released MCP-1, GROα and IL-8, but not MIP-1α or MIP-1β, while BMSC from ND constitutively released only IL-8 and MCP-1. IL-8, GROα and RANTES production in basal conditions was significantly higher in RA patients than in ND. RANTES production was also higher in OA and RA than in PT patients. The combination of TNF-α and IL-1β synergistically increased the production of all chemokines tested except for RANTES. Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) demonstrated that all chemokines not detectable in the supernatants were expressed at the mRNA level. Chemokine immunostaining was localized around the nuclei. This work demonstrates that BMSC from subchondral bone produce chemokines and indicates that these cells could actively participate in the mechanisms directly or indirectly causing cartilage destruction and bone remodelling.

Keywords: chemokines, bone marrow stromal cells, cytokines

INTRODUCTION

Chemokines are a novel class of small cytokines, widely studied for their ability to activate leucocytes and their potential role as mediators in inflammation. These proteins are produced by a wide variety of cell types in response to exogenous stimuli and endogenous mediators such as IL-1, tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) [1,2]. Chemokines have been divided into two subgroups: α or CXC (IL-8, GROα) and β or CC (MCP-1, RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β), based on overall sequence homology, according to the position of the first two conserved cysteines, and the chromosomal location of the corresponding genes. In humans, CXC chemokines are predominantly chemotactic for neutrophils and lymphocytes, while CC chemokines are chemotactic for monocytes, lymphocytes, eosinophils and basophils [1–5]. Studies of chemokine expression have provided strong evidence of their involvement in rheumatic diseases [1,6]. In particular, after stimulation with TNF-α and IL-1β, chondrocytes can produce chemokines which recruit mononuclear cells involved in the degradation of extracellular matrix and changes in chondrocyte function that are thought to play a key role in inflammatory and degenerative joint diseases [6–8].

RA is a systemic autoimmune disorder of unknown aetiology characterized by marked synovial mononuclear cell infiltration and increased levels of proteolytic enzyme that cause degradation of cartilage matrix and progressive joint destruction [9,10].

OA is characterized by progressive loss of cartilage matrix with eventual exposure of bone that it is believed to be due to alterations in chondrocyte activity triggered by injury, genetic abnormalities or disease [11,12].

In these diseases the pathophysiological mechanisms leading to synovial inflammation and cartilage damage have been widely investigated. Little attention, however, has been paid to the role of cells belonging to subchondral bone, in particular bone marrow stromal cells (BMSC). This population, that includes osteoblast and chondrocyte progenitors [13], is important in haematopoiesis—supporting the growth and development of lymphocytes both by producing a variety of cytokines and by cell–cell contact [14,15]. Stromal cells, which are located in bone lacunae, can actively participate in the bone and cartilage changes which occur in inflammatory and degenerative joint diseases both by migrating from underlying bone and by producing cytokines and growth factors in the microenvironment, which can influence cell activation and migration. Moreover, BMSC produce a chemokine (SDF-1) of the CXC group that stimulates proliferation of B cell progenitors [16] and BMSC lines from RA patients have an enhanced ability to support the growth of pre B cells [17].

To assess the role of BMSC in releasing chemokines involved in inflammatory and degenerative joint diseases, we analysed their production and mRNA expression by BMSC isolated from RA, OA, post-traumatic (PT) patients and normal donors (ND).

Our data indicate that high levels of RANTES were constitutively produced by BMSC from RA and in a lesser amount from OA patients. Significant levels of IL-8, GROα and MCP-1 were constitutively produced by BMSC from RA, OA and PT patients, but not MIP-1α or MIP-1β. BMSC also expressed mRNA for chemokines not produced as protein. IL-1β and TNF-α in combination up-regulated the production of all chemokines tested except for RANTES.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

Bone marrow was obtained from eight patients with RA (two male, six female; 64 ± 11 years old (mean ± s.d.); disease duration 6 ± 4 years; C-reactive protein (CRP) 6.15 ± 8.61; erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 41.5 ± 20.6); 18 with OA (10 male, eight female; 59 ± 11 years old; disease duration 4 ± 3 years; CRP 0.72 ± 1.16; ESR 14.3 ± 11.6); eight PT (three male, six female; 66 ± 17 years old; CRP not determined; ESR 40.9 ± 22.1) (post-traumatic after fall) undergoing selective total joint replacement of the hip; and four ND undergoing multiorgan explant for transplantation (30 ± 5 years old). Patients with RA and OA were selected according to the American College of Rheumatology criteria [18,19]. Bone marrow samples were obtained after informed consent and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Istituti Ortopedici Rizzoli (Bologna, Italy).

BMSC isolation

Aspirated subchondral bone marrow was collected in 15-ml tubes containing RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies Ltd, Paisley, UK) plus heparin (20 U/ml). BMSC were obtained as previously described [16]. Briefly, BMSC were isolated using Ficoll–Hypaque density gradient (d = 1.077 g/ml; Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden). The ring was collected and cells were washed twice, resuspended in RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies) with 20% fetal calf serum (FCS; Life Technologies) and seeded at a concentration of 20 × 106 cells/T150 flask. After 1 week non-adherent cells were removed and the adherent BMSC expanded in vitro. Cells were used between the second and third passages of culture.

To assess the absence of haematopoietic cells from BMSC cultures, flow cytometric analysis was performed using MoAb anti-human CD3 (1:10), anti-human CD4 (1:10), anti-human CD8 (1:10), anti-human CD16 (1:10), anti-human CD14 (1:10) and anti-human CD45 (1:10) (all MoAbs were purchased from Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). Briefly, cells were collected after trypsinization (0.2%) and placed for 6 h in 15-ml polyethylene tubes on a racker platform at 37°C to allow the re-expression of markers cleaved during the enzymatic treatment. Cells were incubated with primary MoAb at 4°C for 30 min. BMSC were washed twice, incubated with FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse (Becton Dickinson, Indianapolis, IN) at 4°C for 30 min, fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde and analysed with a FACStar Plus (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA).

Moreover, immunohistochemical procedures were used to characterize BMSC. Unstimulated BMSC (2 × 104) were seeded in eight-well chamber slides (Nunc Inc., Napierville, IL), after 72 h slides were fixed in absolute methanol for 20 min at 4°C and acetone for 10 min at 4°C. Briefly, slides were incubated with the following anti-human MoAbs: anti-CD44 (Dako), anti-collagen type II (Chemicon International Inc., Temecula, CA), anti-collagen type IV (Serotec TD, Oxford, UK), anti-fibronectin, anti-laminin and anti-vimentin (Boehringer, Indianapolis, IN), diluted in 0.01 m PBS pH 7.2 containing 0.25% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma, St Louis, MO) and 0.1% sodium azide for 1 h at room temperature. Slides were washed twice with Tris-buffered saline (TBS) 0.04 m pH 7.6 and then sequentially incubated with goat anti-mouse immunoglobulins conjugated with FITC (1:20; Dako) for 30 min at room temperature.

Isolated BMSC were negative to haematopoietic markers (CD3, CD4, CD8, CD16, CD14, CD45) and strongly positive to CD44, collagen type II, collagen type IV, fibronectin, laminin and vimentin (data not shown).

Chemokine production

BMSC (2 × 104) were seeded in eight-well chamber slides (Nunc) in the following conditions: untreated, activated with IL-1β (0.1, 1 and 10 ng/ml) (specific activity 107 U/mg) or TNF-α (50, 100 and 500 U/ml) (specific activity 108 U/ml) (Boehringer) alone or in combination. After 24 h, 48 h and 72 h supernatants were collected and stored at −20°C. In order to preserve the cells from damage due to freezing, slides were treated with FCS at room temperature for 15 min, dried and stored at −80°C until they were used for chemokine immunolocalization. Concentrations of MCP-1 (sensitivity > 5 pg/ml), IL-8 (sensitivity > 10 pg/ml), RANTES (sensitivity > 5 pg/ml), GROα (sensitivity > 5 pg/ml), MIP-1α (sensitivity > 6 pg/ml) and MIP-1β (sensitivity > 4 pg/ml) were measured using commercial ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Chemokine RNA analysis

Chemokine mRNA expression was evaluated on BMSC both in basal conditions and after activation with IL-1β (10 ng/ml) or TNF-α (500 U/ml) alone or in combination for 19 h at 37°C. Cultured cells were washed twice with PBS–0.1% diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC; Sigma), centrifuged and stored at −80°C as dry pellets.

Total RNA was extracted from cell pellets using the single-step guanidinium-thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform method (RNAzol B solution; Biotecx Labs, Houston, TX).

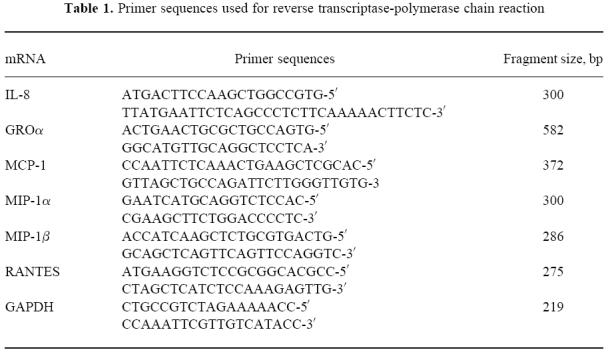

Total RNA (1 μg per reaction) was reverse transcribed using 50 U per reaction of Moloney murine leukaemia virus reverse transcriptase (Perkin Elmer, Norwalk, CT) in the presence of oligo-(dt) (Perkin Elmer) at 42°C for 30 min. The resulting cDNA was amplified using specific primers and a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) Perkin Elmer kit (GeneAmp RNA-PCR) and performing a Hot start procedure with AmpliWax PCR Gem (Perkin Elmer). The respective chemokine primer sequences are given in Table 1. Samples were amplified for 32 cycles at 90°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s in a Gene Amp PCR System 9600 (Perkin Elmer). Amplification of cDNA for the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as internal quality standard. PCR products and a molecular weight marker (123 bp DNA ladder; Life Technologies Ltd) were separated in 2% agarose gel (FMC Bio Products, Rockland, ME), stained with ethidium bromide (10 mg/ml) and bands were visualized and photographed under UV illumination.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction

Chemokine immunolocalization

The eight-well chamber slides at 72 h were fixed using 4% formaldehyde in PBS 0.01 m pH 7.2 plus 0.135% glucose and 0.1% saponin at room temperature for 30 min [20]. Immunoalkaline phosphatase studies were performed using an indirect APAAP method. After fixation, slides were preincubated with PBS containing 2% FCS at 37°C for 30 min, and then incubated with MoAb anti-IL-8, anti-GROα, anti-MCP-1, anti-MIP-1α, anti-MIP-1β and anti-RANTES (1:100; R&D Systems) diluted in RPMI containing 10% FCS and 0.1% saponin, at room temperature overnight. Slides were washed twice with 0.04 m TBS pH 7.6 containing 0.1% saponin and then sequentially incubated twice with rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulins (1:25; Dako) and APAAP mouse (1:50; Dako) at room temperature for 30 min. An alkaline phosphatase reaction using a new fuchsin kit (Dako) was performed at room temperature for 45 min in the presence of 2.2 mg of Levamisole (Sigma) in the substrate. Slides were counterstained with haematoxylin, mounted with glycerine jelly and evaluated in a brightfield microscope.

Negative controls were performed using non-human reactive monoclonal mouse antibody (Dako).

Statistical analysis

The Mann–Whitney U-test and anova Kruskal–Wallis median test were used to analyse the differences in the chemokines produced by BMSC culture supernatants from RA, OA, PT patients and ND. The Wilcoxon matched pairs test was used to analyse the differences among cytokines produced after activation with TNF-α, IL-1β or both in combination.

RESULTS

Chemokine production by BMSC in vitro

In vitro chemokine production by BMSC of RA, OA, PT patients and ND was analysed by ELISA in the supernatants under basal conditions and after activation with TNF-α, IL-1β or both in combination. In preliminary experiments different concentrations of TNF-α (50 U/ml, 100 U/ml, 500 U/ml) and IL-1β (0.1 ng/ml, 1 ng/ml, 10 ng/ml) were tested at 24 h, 48 h and 72 h in order to evaluate the kinetics of chemokine production by BMSC isolated from three RA, three OA, three PT patients and two ND. The highest concentrations in the supernatants for all chemokines (IL-8, GROα, MCP-1, RANTES, MIP-1α and MIP-1β) tested were reached after 72 h using 10 ng/ml of IL-1β and 500 U/ml of TNF-α (data not shown). This time and these agonist concentrations were then used for the subsequent experiments, that were performed on eight RA, 18 OA, eight PT patients and four ND.

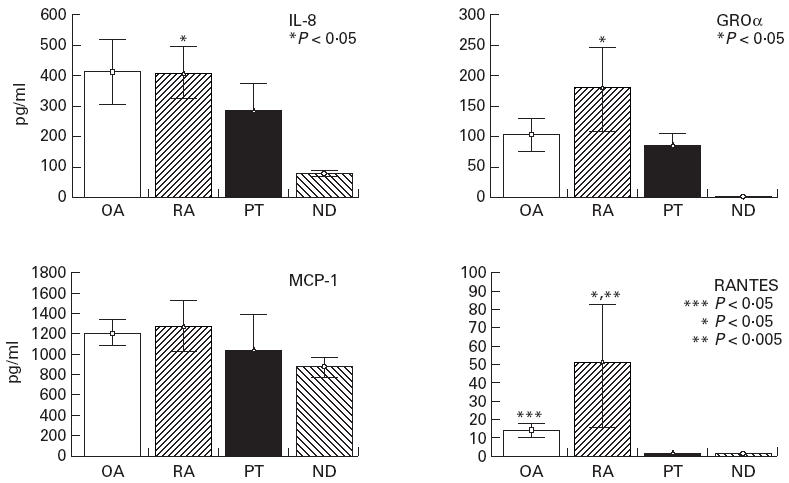

Unstimulated BMSC from ND constitutively released only IL-8 and MCP-1. BMSC from RA, OA and PT patients constitutively released IL-8, GROα, MCP-1, but MIP-1α and MIP-1β were not detectable. RANTES was released only by unstimulated BMSC from RA and OA patients. When the basal production of different chemokines by BMSC isolated from RA, OA, PT patients and ND was compared (Fig. 1), IL-8, GROα and RANTES were found significantly higher in RA patients than in ND (P < 0.05 for each chemokine); moreover, RANTES production was significantly higher in RA and OA than in PT patients (P < 0.005, P < 0.05, respectively).

Fig. 1.

Constitutive production in vitro of IL-8, GROα, MCP-1, RANTES from bone marrow stromal cells (BMSC) isolated from OA, RA post-traumatic (PT) patients and normal donors (ND), evaluated after 72 h of culture as described in Patients and Methods. Data are expressed as means ± s.e.m. of all patients analysed for each group. IL-8, GROα and RANTES production was higher in RA patients than in ND (P < 0.05 for each chemokine). RANTES production was also higher in RA patients than in PT (P < 0.005) and in OA patients than in PT (P < 0.05). *RA versus ND; **RA versus PT; ***OA versus PT.

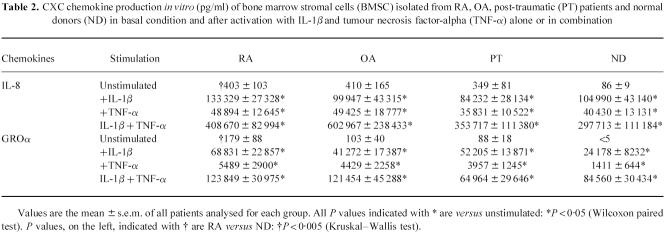

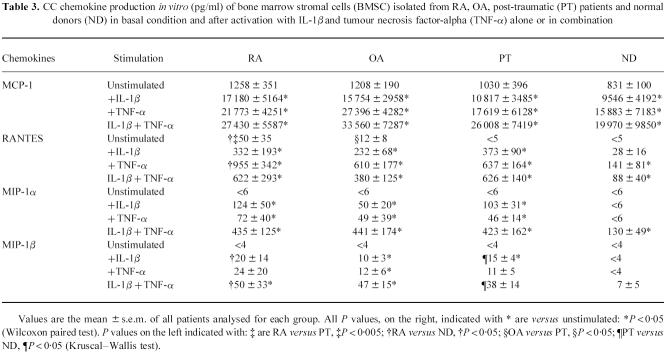

As shown in Tables 2 and 3, for CC and CXC chemokines, the addition of TNF-α and/or IL-1β significantly enhanced chemokine production up to 10-fold the basal conditions. Both TNF-α and IL-1β alone could induce the release of MIP-1α and MIP-1β by BMSC from RA, OA and PT patients, but not by BMSC derived from ND. IL-1β induced two-fold higher IL-8 and 10-fold higher GROα production than TNF-α. By contrast, TNF-α induced three-fold higher RANTES and two-fold higher MCP-1 production than IL-1β. TNF-α plus IL-1β synergistically increased IL-8, GROα, MIP-1α, MCP-1 and MIP-1β, but not RANTES production in all the groups tested. In particular, RANTES production after TNF-α activation was significantly higher in RA patients than in ND (P < 0.05). Similarly, MIP-1β production both after IL-1β and IL-1β+ TNF-α activation was significantly higher in RA and PT patients than in ND (P < 0.05 for both groups).

Table 2.

CXC chemokine production in vitro (pg/ml) of bone marrow stromal cells (BMSC) isolated from RA, OA, post-traumatic (PT) patients and normal donors (ND) in basal condition and after activation with IL-1β and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) alone or in combination

Table 3.

CC chemokine production in vitro (pg/ml) of bone marrow stromal cells (BMSC) isolated from RA, OA, post-traumatic (PT) patients and normal donors (ND) in basal condition and after activation with IL-1β and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) alone or in combination

Chemokine gene expression by BMSC

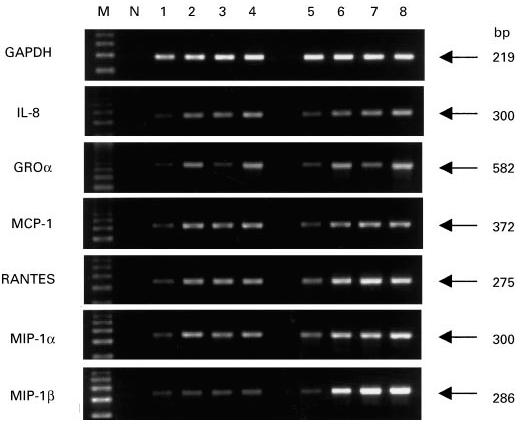

RT-PCR analysis was performed on BMSC from all four groups studied in order to assess the mRNA expression of chemokines that were not detectable in the culture supernatant. Gene transcripts were detected in each condition and for all the chemokines tested. In particular, RANTES and GROα mRNAs were evidenced in ND unstimulated cells and MIP-1α and MIP-1β mRNAs were detected in all four groups of patients (RA, OA, PT and ND) in basal conditions and also in IL-1β- and TNF-α-stimulated ND. Figure 2 shows the representative results obtained from a ND and a RA patient, both in basal and stimulated conditions.

Fig. 2.

Chemokine mRNA expression in bone marrow stromal cells (BMSC) derived from a normal donor (lanes 1–4) and a RA patient (lanes 5–8), in basal and stimulated conditions, analysed by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) as described in Patients and Methods. M, Molecular weight marker (123-bp ladder); N, negative control (no template); lanes 1 and 5, unstimulated BMSC; lanes 2 and 6, BMSC stimulated with IL-1β (10 ng/ml); lanes 3 and 7, BMSC stimulated with TNF-α (500 U/ml); lanes 4 and 8, BMSC stimulated with IL-1β+ TNF-α in combination.

RT-PCR analysis was similar in trend to ELISA data, showing that IL-1β and TNF-α can up-regulate the mRNA expression of these chemokines in BMSC and consequently induce the protein production (Tables 2 and 3). Moreover, consistent with the data on protein secretion, a higher mRNA expression could be observed in RA patients than in ND for the following chemokines: GROα and RANTES in basal conditions, RANTES after TNF-α stimulation and MIP-1β after IL-1β or IL-1β plus TNF-α stimulation.

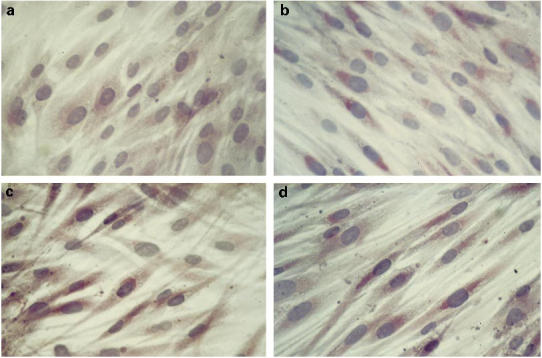

Chemokine immunolocalization by BMSC in vitro

Immunohistochemical analysis was performed to further evaluate chemokine localization inside the BMSC. All chemokines tested were localized mainly around the nuclei of BMSC, suggesting an accumulation of the secreted chemokine into the Golgi complex, and the staining was stronger after IL-1β and TNF-α treatment (Fig. 3). The intensity of immunostaining seemed to be well related to chemokine production tested in the cell culture supernatants (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Immunostaining of MIP-1α in bone marrow stromal cells (BMSC) isolated from subchondral bone of unstimulated normal donor (ND) (a), IL-1β + TNF-α–activated ND (b), OA patient (c), RA patient (d), evaluated after 72 h of culture.

DISCUSSION

RA and OA are two diseases characterized by destruction of the cartilage and subsequent modification of the underlying bone. Although the initial events leading to articular damage differ significantly in RA and OA, they share some similar pathophysiological mechanisms. In RA, chondrocyte-mediated extracellular matrix degradation can be dependent on the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines (mainly IL-1β and TNF-α) from the synovial infiltrate. Chondrocytes under appropriate immune- and non-immune-mediated stimulation can actively participate in the inflammation by releasing chemokines (e.g. IL-8, MCP-1, MIP-1α) which can trigger the recruitment of mononuclear cells and granulocytes in the site of inflammation [21]. The mechanisms leading to cell infiltration of the synovium and cartilage degeneration have recently been elucidated, but little information is available on the role of cells from the subchondral bone compartment. BMSC, which are located in the bone lacunae, are the precursors of at least five cell types of connective tissues (bone, cartilage, adipose tissue, fibrous tissue and haematopoietic-supporting reticular stroma). Here we report evidence that BMSC of inflammatory or degenerative arthritis from patients with RA and OA can release into the microenvironment important chemokines, which may be involved in the pathogenesis of these diseases.

The main findings of our study are: (i) unstimulated subchondral BMSC from ND secrete in vitro only small amounts of IL-8 and MCP-1, while significantly higher levels of IL-8, GROα and RANTES are produced by unstimulated BMSC from patients with RA; (ii) RANTES production is also more elevated in RA and OA than in PT patients; (iii) BMSC express mRNA for all chemokines not detectable as protein; (iv) IL-1β and TNF-α, alone or in combination, up-regulate chemokine production. A synergistic effect is observed for all chemokines except for RANTES production, which is down-regulated by the addition of both stimulants.

All these data suggest that subchondral BMSC, which are in close contact with the joint, are differentially activated in RA and OA and can actively participate in these diseases by releasing important chemoattractants able to induce accumulation and activation of other cell types (e.g. leucocytes, fibroblasts, chondrocytes). Previous studies demonstrated that synovial fibroblasts derived from patients with RA and OA can secrete proinflammatory chemokines. MIP-1α is produced by fibroblasts from RA [22] and MIP-1β from OA [23], only after stimulation with IL-1β and TNF-α. Although synovial fibroblasts and BMSC belong to the same lineage, these populations present important differences. Subchondral BMSC constitutively express mRNA, and the protein for a wide variety of CC and CXC chemokines seems to be preactivated in vitro in inflammatory arthritis and responds to IL-1β and TNF-α stimulation with a much higher increase in chemokine production than that reported for synovial fibroblasts [22,23].

All these findings strongly suggest that by releasing several chemokines, BMSC are involved in the pathophysiology of RA and OA, although the specific role and the main target of each chemokine remain to be determined.

IL-8, GROα (member of CXC family) and MCP-1 (member of CC family), released spontaneously at high levels from BMSC of RA, OA and PT patients, are major mediators of inflammation able to cause joint damage indirectly. These chemokines are chemoattractants for neutrophils (IL-8 and GROα) and monocytes (MCP-1) and they also show specific biological activities that could exacerbate the disease [4,6]. In particular, GROα that is not produced in basal conditions by BMSC from ND, is a potent inducer of tissue inhibitor metalloproteinases (TIMPS) [24,25], indicating that it can directly influence cartilage matrix degradation.

RANTES (a member of the CC family) is constitutively released by BMSC from RA patients, and in lower amounts from OA patients. The spontaneous elevated production of RANTES from RA patients may be related to the high level of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β and TNF-α) present in the articular microenvironment in this disease. It is noteworthy that stimulated BMSC from RA patients produce significantly more RANTES than ND (after TNF-α activation) and more MIP-1β than PT patients (after IL-1β or IL-1β plus TNF-α activation). These data suggest again that BMSC from RA patients are more prone to respond to inflammatory stimuli and it could be hypothesized that the elevated local concentrations of TNF-α and IL-1β during RA flares are able to induce on these cells a higher expression of cytokine receptors. RANTES has some peculiar properties that can be related to the pathogenesis of RA. This chemokine is also highly expressed by synovial T cells in basal conditions and by human rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts after TNF-α or IL-1β stimulation [26,27], indicating that it can play a role in exacerbating the disease.

BMSC from all the groups studied failed to produce IL-1β and TNF-a, either in basal conditions or after activation (TNF-α and IL-1β, respectively) (data not shown), but the single or combined action of these two cytokines induced a 10-fold higher production of the chemokines analysed, as also reported for other cell types [26,28]. IL-1β and TNF-α are proinflammatory cytokines actively secreted by the synovial infiltrates in RA and OA, which stimulate the recruitment of leucocytes to the damaged tissue through the production of chemokines [21,29]. Our data indicate that in BMSC IL-1β selectively increases IL-8 and GROα levels more than MCP-1 and RANTES, while TNF-α preferentially induces MCP-1 and RANTES rather than IL-8 and GROα, indicating a different regulation pattern of these chemokines. The combination of IL-1β and TNF-α significantly increased chemokine production except for RANTES. Rathanaswami et al. [26] also reported that the combination of these two cytokines reduces the levels of RANTES mRNA expressed by synovial fibroblasts from RA.

In conclusion, this study has shown that stromal cells present in the bone compartment can release chemokines that can be involved in the joint damage in RA and OA and may affect the haematopoietic system since, as reported for MIP-1α and MCP-1 [30,31], they can inhibit the proliferation of haematopoietic stem cells in vitro and in vivo. Chemokine release from BMSC is finely regulated, and different receptors and activation pathways can act synergistically, triggering or inhibiting the expression of chemokine genes. The recent observation that chemokines influence osteoclast and osteoblast functions [32,33] and consequently act on bone remodelling can help to explain the modifications of underlying articular bone which occur in RA and OA.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Mariagrazia Uguccioni (Theodor Kocher Institut, Bern, Switzerland) for her helpful advice, Dr Franco Piras for statistical analysis, and Patrizia Rappini and Luciano Pizzi for editorial and technical assistance. This work was supported by grants from Istituti Ortopedici Rizzoli, Bologna, Italy, and MURST, Università degli Studi di Bologna, Italy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baggiolini M, Dewald B, Moser B. Interleukin-8 and related chemotactic cytokines CXC and CC chemokines. Adv Immunol. 1994;55:97–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baggiolini M, Dewald B, Moser B. Human chemokines: an update. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:675–705. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baggiolini M. Chemokines and leukocyte traffic. Nature. 1998;392:565–8. doi: 10.1038/33340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adams DH, Lloyd AR. Chemokines: leucocyte recruitment and activation cytokines. Lancet. 1997;349:490–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)07524-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahuja SK, Gao JL, Murphy PM. Chemokine receptors and molecular mimicry. Immunol Today. 1994;15:281–7. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kunkel SL, Lukacs N, Kasama T, Strieter RM. The role of chemokines in inflammatory joint disease. J Leucocyte Biol. 1996;59:6–12. doi: 10.1002/jlb.59.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Villiger PM, Terkeltaub R, Lotz M. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) expression in human articular cartilage. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:488–96. doi: 10.1172/JCI115885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Recklies AD, Golds EE. Induction of synthesis and release of interleukin-8 from human articular chondrocytes and cartilage explants. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:1510–9. doi: 10.1002/art.1780351215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bodman KB, Roitt IM. The pathophysiology of rheumatoid arthritis. Fundam Clin Immunol. 1994;2:73–81. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilder RL. Rheumatoid arthritis. A epidemiology, pathology and pathogenesis. In: Schumacher HR, Klippel JH, Koopman WJ, editors. Primer on the rheumatic diseases. 10. Atlanta: Arthritis Foundation; 1993. pp. 86–89. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brandt KH, Slemenda CW. Osteoarthritis. A. Epidemiology, pathology and pathogenesis. In: Schumacher HR, Klippel JH, Koopman WJ, editors. Primer on the rheumatic diseases. 10. Atlanta: Arthritis Foundation; 1993. pp. 184–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamerman D. The biology of osteoarthritis. New Engl J Med. 1989;320:1322–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198905183202006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedenstein AJ. Osteogenic stem cells in the bone marrow. Bone Miner Res. 1990;7:243–71. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kincade PW, Lee G, Pietrangeli CE, Hayashi S-I, Gimble JM. Cells and molecules that regulate B lymphopoiesis in bone marrow. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:111–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.000551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dorshkind K. Regulation of hemopoiesis by bone marrow stromal cells and their products. Annu Rev Immunol. 1990;8:111–37. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.000551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaisho T, Oritani K, Ishikawa J, Tanabe M, Muraoka O, Ochi T, Hirano T. Human bone marrow stromal cell lines from myeloma and rheumatoid arthritis that can support murine pre-B cell growth. J Immunol. 1992;149:4088–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagasawa T, Hirota S, Tachibana K, et al. Defects of B-cell lymphopoiesis and bone-marrow myelopoiesis in mice lacking the CXC chemokine PBSF/SDF-1. Nature. 1996;382:635–8. doi: 10.1038/382635a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D. Development of criteria for the classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;20:1039–49. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arnett FC, Edwortht SM, Bloch DA, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315–24. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sander B, Andersson J, Andersson U. Assessment of cytokines by immunofluorescence and the parafolmaldehyde-saponin procedure. Immunol Rev. 1991;119:65–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1991.tb00578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.del Pozo MA, Sanchez-Mateos P, Sanchez-Madrid F. Cellular polarization induced by chemokines: a mechanism for leukocyte recruitment? Immunol Today. 1996;17:127–31. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)80604-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koch AE, Kunkel SL, Harlow LA, Mazarakis DD, Haines GK, Burdick MD, Pope RM, Strieter RM. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1α. A novel chemotactic cytokine for macrophages in rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:921–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI117097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koch AE, Kunkel SL, Shah MR, et al. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1β: a C-C chemokine in osteoarthritis. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1995;77:307–14. doi: 10.1006/clin.1995.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hogan M, Sherry B, Ritchlin C, et al. Differential expression of the small inducible cytokines GROα and GROβ by synovial fibroblasts in chronic arthritis: possible role in growth regulation. Cytokine. 1994;6:61–69. doi: 10.1016/1043-4666(94)90009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Unemori EN, Marsters JC, Bauer EA, Amento EP. The product of the GRO gene regulates collagen turnover by inducing tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34:S117. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rathanaswami P, Hachicha M, Sadick M, Schall TJ, McColl SR. Expression of the cytokine of RANTES and interleukin-8 genes by inflammatory cytokines. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:5834–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robinson E, Keystone EC, Schall TJ, Gillet N, Fish EN. Chemokine expression in rheumatoid arthritis (RA): evidence of RANTES and macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1β production by synovial T cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;101:398–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb03126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sticherling M, Kupper M, Koltrowitz F, et al. Detection of the chemokine RANTES in cytokine-stimulated human dermal fibroblasts. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;105:585–91. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12323524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sipe JD, Martel-Pelletier J, Otterness IG, Pelletier JP. Cytokine reduction in the treatment of joint conditions. Med Inflamm. 1994;3:243–56. doi: 10.1155/S0962935194000359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cashman JD, Eaves CJ, Sarris AH, Eaves AC. MCP-1, not MIP-1α, is the endogenous chemokine that cooperates with TGF-β to inhibit the cycling of primitive normal but not leukemic (CML) progenitors in long-term human marrow cultures. Blood. 1998;92:2338–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cook DN. The role of MIP-1a in inflammation and hematopoiesis. J Leukocyte Biol. 1996;59:61–66. doi: 10.1002/jlb.59.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MacDonald BR, Gowen M. Cytokines and bone. Br J Rheumatol. 1992;31:149–55. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/31.3.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fuller K, Owens JM, Chambers TJ. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1α and IL-8 stimulate the motility but suppress the resorption of isolated rat osteoclasts. J Immunol. 1995;154:6065–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]