Abstract

Cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) leads to a systemic inflammatory response with secretion of cytokines. Alterations in the serum concentrations of cytokines have important prognostic significance. Reports on cytokine release during cardiac surgery with CPB have yielded conflicting results. Haemodilution occurs with the onset of CPB resulting in large fluid shifts during the perioperative course of cardiac procedures. In the present study we compare the perioperative course of serum concentrations of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10 and sIL-2R with and without correction for haemodilution in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery. Twenty male patients undergoing elective CABG surgery with CPB and general anaesthesia using a balanced technique with sufentanil, isoflurane and midazolam were enrolled into the study. Serum levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10 and sIL-2R were measured using commercially available ELISA kits. Simultaneous haematocrit values were obtained at all sample times. Statistical analysis was performed by non-parametric analysis of variance and t-tests for data corrected for haemodilution and data that were not corrected for haemodilution. Adjusted significance level was P < 0.01. Intra-operatively, up to the second post-operative day PCV values were significantly decreased compared with preoperative values. Cytokine measurements not corrected for haemodilution were significantly lower than the corrected values. The perioperative haemodilution and decrease in PCV may lead to an underestimation of the cytokine secretion in post-operative patients. We conclude that cytokine measurements were significantly influenced by the perioperative haemodilution and the subsequent decrease in PCV and may in part account for the varying results reported in the literature regarding cytokine release in patients undergoing CABG surgery.

Keywords: cytokine, cardiac surgery, cardiopulmonary bypass, haematocrit, tumour necrosis factor-alpha, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, sIL-2R, haemodilution

INTRODUCTION

Cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) provokes a systemic inflammatory response with secretion of cytokines [1,2]. Alterations in the serum concentrations of cytokines have important prognostic significance [3].

The perioperative secretion of cytokines is the result of a number of processes that occur during cardiac surgery with CPB: immunomodulatory effects of anaesthesia and drugs administered perioperatively [4], tissue damage, contact activation of the blood with non-endothelial surfaces of the extracorporeal circulation tubing, hyperthermia during rewarming, development of cardiac ischaemia with subsequent reperfusion injury, and the likelihood of endotoxaemia [1,5–8]. The inflammatory response that continues to be present following cardiac surgery is assumed to be the cumulative effect of the above mentioned factors on the immune system [1]. Interpretation of these changes may be complicated by changes in fluid balance.

Cardiac procedures are accompanied by large fluid shifts perioperatively [2]. Haemodilution is a standard practice during CPB [9]. Marked haemodilution occurs at the onset of CPB and results in moderate (> 25%) to severe (< 20%) reduction of the patients' haematocrit values [10].

Reports on cytokine release during coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery with CPB have yielded conflicting results. Hall et al. [1] reports variable detection of certain cytokines after CABG surgery as well as differences in the time course for peak levels of the measured cytokines. There are numerous reasons for these differences: the timing of samples, assay sensitivities, circadian variations in cytokine release, the short half-life of TNF-α and IL-1β may all influence the measurement of the desired parameters during CABG surgery [1,11,12].

In addition, cytokine measurements are influenced by haemodilution. Patient variability in the extent of haemodilution may also account for the observed interpatient discrepancy of cytokine release in the cardiac surgery patient.

At present, little information is available about the effect of perioperative haemodilution on serum concentrations of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. To our knowledge there has been no study that corrected observed cytokine values for the concomitantly occurring haemodilution. The objective of the present study was to compare blood levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10 and sIL-2R with and without correction for haemodilution in patients undergoing CABG surgery.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

After approval by the institutional review board, written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Subjects

Twenty male patients scheduled for elective CABG surgery without known immune, renal or central nervous system dysfunction were enrolled in the study. Patients with pre-existent congestive heart failure, exogenous hormone therapy, chronic renal failure, malignancy past or present, infection, inflammation, acute myocardial infarction within 6 weeks, malnutrition or with diabetes mellitus type I were excluded from this study.

Study design

Study design, cardiopulmonary bypass technique and cytokine determinations were identical to those described previously [13].

Premedication consisted of oral flunitrazepam 1 mg on the evening of surgery and on call to the operating room (OR). Induction of anaesthesia was achieved by administering midazolam 0.05 mg/kg, sufentanil 1 μg/kg, and etomidate 0.2 mg/kg. Endotracheal intubation was performed following relaxation with pancuronium 0.1 mg/kg. Anaesthesia was maintained with continuous infusions of sufentanil 0.1 μg/kg per h and midazolam 0.03 mg/kg per h. End-tidal concentrations of isoflurane were titrated between 0.4 vol% and 0.8 vol% according to the clinical situation. Repetitive doses of pancuronium 0.03 mg/kg were given on an hourly basis to maintain adequate neuromuscular blockade. Controlled mechanical ventilation (CMV) using an air in oxygen mixture with an inspired oxygen concentration (FIO2) between 0.33 and 1.0 was instituted, keeping the arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) > 100 mm of mercury (mmHg). In normovolaemic patients, arterial hypotension (mean arterial pressure (MAP) < 70 mmHg) was treated with a dopamine infusion at 2–5 μg/kg per min. Hypertension (systolic blood pressure > 140 mmHg) was treated with a nitroglycerin infusion at 1–2 μg/kg per min. Following surgery, all patients remained intubated and artificially ventilated in the intensive care unit (ICU) until they regained sufficient spontaneous respiration. During this time, the sufentanil infusion was continued for sedation at 0.01–0.02 μg/kg per h. All extubations took place upon stable cardiovascular and respiratory conditions of the patients.

During the period of data sampling, patients received no medication containing steroids.

Cardiopulmonary bypass

CPB was conducted using non-heparin-coated circuits and a membrane oxygenator (Stöckert Instruments, Mutz an der Knatter, Germany). Upon initiation of CPB, 18 patients were cooled to 28–32°C, two patients were cooled to 35°C. Pump prime consisted of 1000 ml of Ringer's solution, 250 ml of human albumin 5% and 250 ml mannitol solution 20%. Pump flow (non-pulsatile) was maintained at 2.4 l/m2 body surface area (BSA)/min. Saint Thomas' Hospital crystalloid cardioplegic solution (600 ml) was injected in the aortic root immediately after cross-clamping of the aorta to achieve cardiac arrest. Additional cardioplegia was administered in 200-ml increments every 30 min to maintain cardiac stand still.

Blood samples

Time and route of collection of blood samples were as follows. Preoperatively between 6 and 8 p.m., before premedication (T1), intra-operatively 90 min after incision, on bypass (T2), and post-operatively between 6 and 8 p.m. on the day of surgery (T3), as well as between 6 and 8 p.m. on the first (T4) and second (T5) post-operative day.

Blood samples were obtained from an i.v. sampling catheter. The blood was spun down for 10 min in a centrifuge at 1000 g and −10°C 10 min after drawing. The serum was stored at −80°C until it was assayed. In four patients of the study group it was not possible to obtain blood samples on the second post-operative day. Since most CABG patients leave our hospital on the second or third post-operative day to undergo cardiac rehabilitation programmes elsewhere, blood sampling was possible up to post-operative day 2.

Analytical methods

The concentrations of the cytokines IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α and sIL-2R were measured in quantitative sandwich ELISA. Only commercial kits were used (Quantikine; R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK). If the original analysis of a certain specimen was out of range, we conducted follow-up analyses from the original specimen. In order to take perioperative blood volume changes into account, blood sampling for cytokine and packed cell volume (PCV) was performed simultaneously. PCV was computed from erythrocyte count and mean cellular volume. Correction of the dilution effect for cytokine determinations with regards to PCV was made according to a formula described by Taylor et al. [10]: PCV-corrected cytokine (pg/ml) =(cytokine (pg/ml) × preoperative PCV)/PCV at time of sampling.

According to the information of the manufacturer, sensitivities for the assays were: TNF-α < 180 fg/ml, IL-6 assay 0.70 pg/ml, IL-1β assay < 100 fg/ml, and sIL-2R assay 24 pg/ml. Intra-assay coefficients were 5.6–6.1% for TNF-α, 8.0–11.8% for IL-1β, 3.2–8.5% for IL-6, 4.6–6.1% for sIL-2R and 2.3–7.5% for IL-10 assay. Interassay coefficients were 7.5–10.4% for TNF-α, 7.1–11.1% for IL-1β, 3.5–8.7% for IL-6, 6.0–7.2% for sIL-2R, 3.7–7.6% for IL-10.

For IL-10 blood samples were assayed with an ultrasensitive sandwich-type ELISA (Cytoscreen, Laboserv GmbH Diagnostica, Giessen, Germany). The lower limit of quantification was quoted as < 208 fg/ml.

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) was used for the analysis of the data. Serial data corrected for haemodilution and not corrected for haemodilution were evaluated by the repeated measures analysis of variance and then by paired t-tests, except for IL-10. For IL-10 non-parametric analysis of variance separating data corrected for haemodilution and data that were not corrected for haemodilution was performed. Post hoc comparisons and comparisons between values corrected for haemodilution and non-corrected values were done with Wilcoxon–Wilcox tests. Spearman's rank correlation coefficients were computed for the determination of relationships between measurements. The significance level was set two-sided with α = 0.05.

RESULTS

Demographic data of the study participants and details of surgery are given in Table 1. Intra-operatively, during CPB, the PCV decreased significantly in all studied patients compared with the preoperatively obtained values (0.43% preoperative versus 0.27% intra-operative). The decrease in PCV was classified in four cases as minimal (PCV > 30%), in eight cases as moderate (PCV > 25%) and in eight cases as severe (PCV < 25%).

Table 1.

Description of the study participants (n = 20)

CPB, Cardiopulmonary bypass.

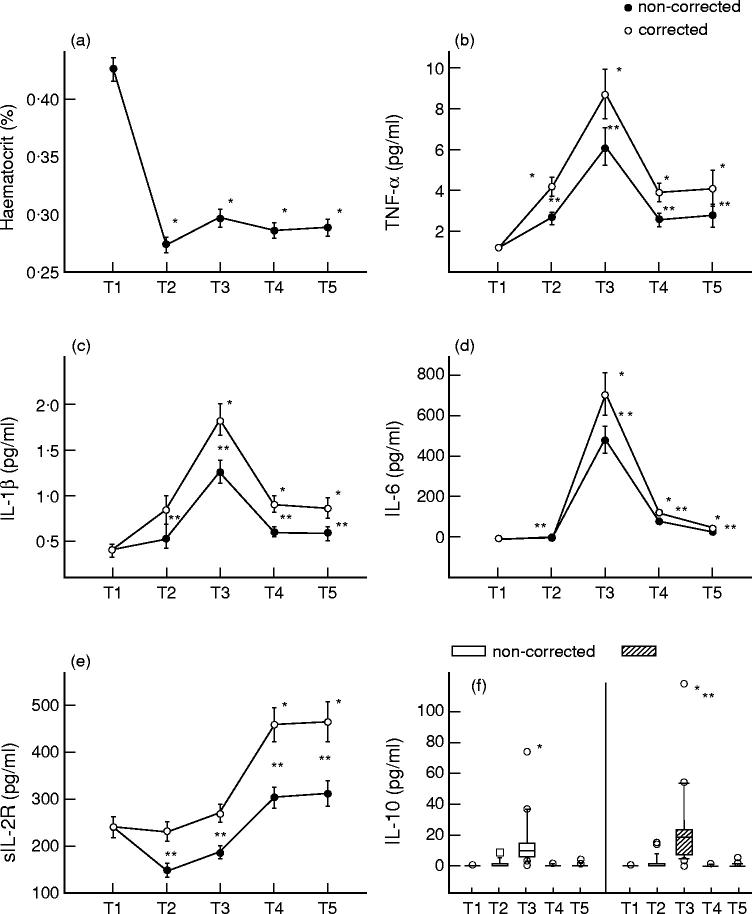

In the post-operative period up to the second post-operative day, PCV remained significantly decreased compared with the baseline values (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Haematocrit (a), TNF-α (b), IL-1β (c), IL-6 (d), sIL-2R (e) and IL-10 (f) blood levels of 20 patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting surgery preoperative (T1), intra-operative, during cardiopulmonary bypass (T2), post-operative, on day of surgery (T3), the first (T4) and second (T5) post-operative day with and without correction for haemodilution. Results are expressed as mean value ± s.e.m. (a–e) and the median with 25 and 75 percentiles (f). *Significant differences compared with preoperative values; **significant differences between values corrected for haemodilution and non-corrected values.

Intra- and post-operative values of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and sIL-2R not corrected for haemodilution were significantly lower than haemodilution-corrected values (P < 0.001). Intra-operatively, non-corrected concentrations of sIL-2R were significantly lower compared with the preoperative values.

TNF-α was detected in all patients throughout the study period. Intra- and post-operatively up to the second post-operative day, serum levels of TNF-α were significantly elevated compared with preoperative measurements (Fig. 1b). Post-operatively, on the day of surgery, serum concentrations of TNF-α were maximally increased. They were also significantly correlated with TNF-α values obtained at the first (r = 0.665; P = 0.002) and second (r = 0.624; P = 0.01) post-operative day.

Preoperatively, serum levels of IL-1β were not detectable in three study participants. Intra-operatively IL-1β was detected in 19 out of 20 enrolees. Post-operatively, sufficient serum levels of IL-1β were found in all studied patients. Post-operatively, up to the second post-operative day, serum concentrations of IL-1β were significantly increased compared with preoperative values (Fig. 1c).

Serum concentrations of IL-6 were demonstrable throughout the study period. Post-operatively, up to the second post-operative day, serum levels of IL-6 were significantly elevated compared with their pre- and intra-operative measurements (Fig. 1d).

Serum concentrations of IL-10 were detected preoperatively in one, intra-operatively in six, post-operatively, on the day of surgery in 19, on the first post-operative day in three and on the second post-operative day in four cases of all study participants. Post-operatively, at T3 blood levels of IL-10 were significantly elevated compared with the pre- and intra-operative measurements.

DISCUSSION

The present study investigated the perioperative time course of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in 20 male patients undergoing elective CABG surgery with and without correction of the cytokine measurements for haemodilution.

A persistent effect of haemodilution up to the second post-operative day was found in the study participants. In agreement with the results of other studies [10] intra-operatively obtained PCV values were significantly decreased compared with the preoperative measurements. Starting from the time of the initial haemodilution (i.e. initiation of CPB), PCV values remained decreased up to the second post-operative day.

During the study period, cytokine measurements not corrected for haemodilution were significantly lower compared with corrected measurements. For example, intra-operatively obtained, non-corrected serum levels of sIL-2R were found to be significantly decreased compared with their preoperative values. This finding can be interpreted as an epiphenomenon: low levels of sIL-2R arise as a consequence of the haemodilution that occurs invariably with the initiation of CPB.

Since haemodilution may be only one of several factors affecting cytokine measurements following the employment of CPB, it can be assumed that the true levels of the investigated substances lie in the range between corrected and non-corrected values. The effect of haemodilution, due to perioperative transfusion of fluids, on the concentration of serum constituents can be corrected by several formulae based on alterations in the PCV [14].

Attempts have been made to determine the most appropriate method of correcting concentrations of plasma and serum constituents for the effect of haemodilution, so that concomitant or subsequent non-dilutional changes, resulting from surgical trauma, could be detected [14]. The results of the study of Taggart et al. [14] suggest that none of the currently available formulae can consistently correct for the effect of haemodilution in vivo. At present the most appropriate correctional formula for comparative studies, examining sequential changes in the immediate as well as late period after haemodilution, seem to be uncertain [14]. The formula used in our study provides an easily applicable correction factor and has been found to correct appropriately for the effects of haemodilution in the post-operative period in vivo, while underestimating the effects of haemodilution in vitro [14].

Cardiac surgery involving cardiopulmonary bypass requires a correction for marked haemodilution as a large volume of fluid is added to the circulation in a relatively short period of time [14].

Our data demonstrate that cytokine measurements are significantly influenced by haemodilution and the consecutive decrease in PCV and may in part account for the widespread differences of cytokine measurements cited in the literature for CABG surgery patients. The perioperative haemodilution and the subsequent decrease in PCV may lead to an underestimation of cytokine secretion in post-operative patients. The ability to correct for haemodilution is of clinical value, since measurements of serum cytokine concentrations are used as markers of the inflammatory response to surgery and have been reported to provide prognostic value for patients with sepsis syndrome [3].

The extent of cytokine secretion and systemic inflammatory response in association with and following CPB has been enlisted to help in the risk stratification of surgical and critically ill patients. TNF-α and IL-1β are mediators of the host inflammatory reaction, i.e. post-operative fever and symptoms of acute-phase reactions [1]. Common post-operative problems associated with CPB, i.e. coagulopathy, increased capillary permeability, fever, multisystem organ failure, have been assumed to be manifestations of the profoundly altered immune functions following cardiac surgery [6,12,15–17]. Sawa et al. [18] demonstrated the negative impact of the inflammatory response initiated by CPB on myocardial recovery after cross-clamping of the aorta. Hennein et al. [19] showed that TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 can serve as markers for myocardial ischaemia and dysfunction.

Several studies describe an increase in blood levels of IL-6 in patients undergoing cardiac surgery [6,20–23]. IL-6 is recognized as an early and robust marker of the systemic inflammatory response following surgery [24,25]. Cruickshank et al. [24] reported that the amount of secretion of IL-6 in surgical patients has a positive correlation with the extent of surgical injury. In accordance with our results in the cardiac surgery population, they describe increased blood levels of IL-6 with peak levels 6–12 h after incision in patients undergoing abdominal surgical procedures. Peak levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-10 were found in our study participants also in the post-operative period.

In conclusion, we report the consecutive changes in pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine levels corrected for haemodilution in patients undergoing CABG surgery. Intra-operatively, up to the second post-operative day, PCV values were significantly decreased compared with the preoperative values. Cytokine measurements not corrected for haemodilution were significantly lower than the corrected values. Post-operatively, on the day of surgery, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-10 were maximally elevated compared with the preoperative values. We conclude that cytokine measurements are significantly influenced by haemodilution and the decrease in PCV. This finding may in part account for the variable results for cytokine release in CABG surgery patients that are cited in the literature.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mrs Bianca Sternberg, Institute of Immunology and Transfusion Medicine, Medical University of Lübeck, for the processing of the cytokine assays, Professor Dr H. H. Sievers, Chairman of the Department of Cardiac Surgery, who gave permission to perform the study in his department, PD Dr H. J. Friedrich, Associate Professor of Biomedical Statistics, for his help with the statistical analysis of the data, Ms Angret Daher for her help with the manuscript, and Ms Johanna Schwarzenberger MD, Assistant Professor of Clinical Anaesthesiology St Luke's-Roosevelt Hospital Center, Columbia University, NY, for her constructive criticism and helpful review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hall RI, Smith MS, Rocker G. The systemic inflammatory response to cardiopulmonary bypass: pathophysiological, therapeutic, and pharmacological considerations. Anesth Analg. 1997;85:766–82. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199710000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herskowitz A, Mangano DT. Inflammatory cascade. A final common pathway for perioperative injury? Anesthesiology. 1996;85:957–60. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199611000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackwell TS, Christman JW. Sepsis and cytokines. Br J Anaesth. 1996;77:110–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/77.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McBride WT, Armstrong MA, McBride SJ. Immunomodulation: an important concept in modern anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 1996;51:465–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1996.tb07793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marti F, Munoz J, Peiro M, et al. Higher cytotoxic activity and increased levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass. Am J Hematol. 1995;49:237–9. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830490310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abe K, Nishimura M, Sakakibara T. Interleukin-6 and tumour necrosis factor during cardiopulmonary bypass. Can J Anaesth. 1994;41:876–7. doi: 10.1007/BF03011610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Westaby S. Organ dysfunction after cardiopulmonary bypass. A systemic inflammatory reaction initiated by the extracorporeal circuit. Intens Care Med. 1987;13:89–95. doi: 10.1007/BF00254791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butler J, Pillai R, Rocker GM, Westaby S, Parker D, Shale DJ. Effect of cardiopulmonary bypass on systemic release of neutrophil elastase and tumor necrosis factor. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1993;105:25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liam BL, Plöchl W, Cook DJ, Orszulak TA, Daly RC. Hemodilution and whole body oxygen balance during normothermic cardiopulmonary bypass in dogs. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;115:1203–8. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(98)70422-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor KM, Bain WH, Jones JV, Walker MS. The effect of hemodilution on plasma levels of cortisol and free cortisol. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1976;72:57–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inaba H, Kochi A, Yorozu S. Suppression by methylprednisolone of augmented plasma endotoxin-like activity and interleukin-6 during cardiopulmonary bypass. Br J Anaesth. 1994;72:348–50. doi: 10.1093/bja/72.3.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frering B, Philip I, Dehoux M, Rolland C, Langlois JM, Desmonts JM. Circulating cytokines in patients undergoing normothermic cardiopulmonary bypass. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;108:636–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roth-Isigkeit A, Schwarzenberger J, von Borstel T, et al. Perioperative cytokine release during coronary artery bypass grafting in patients of different ages. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;114:26–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00682.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taggart DP, Fraser WD, Fell GS, Wheatley DJ, Shenkin A. Plasma albumin and haemodilution: the problem of interpretation in sequential studies. Ann Clin Biochem. 1989;26:132–6. doi: 10.1177/000456328902600207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ide H, Kakiuchi T, Furuta N, et al. The effect of cardiopulmonary bypass on T cells and their subpopulations. Ann Thorac Surg. 1987;44:277–82. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)62074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Misoph M, Babin-Ebell J. Interindividual variations in cytokine levels following cardiopulmonary bypass. Heart Vessels. 1997;12:119–27. doi: 10.1007/BF02767129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalfin RE, Engelman RM, Rousou JA, et al. Induction of interleukin-8 expression during cardiopulmonary bypass. Circulation. 1993;88II:401–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sawa Y, Shimazaki Y, Kadoba K, et al. Attenuation of cardiopulmonary bypass-derived inflammatory reactions reduces myocardial reperfusion injury in cardiac operations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;111:29–35. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(96)70398-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hennein HA, Ebba H, Rodriguez JL, et al. Relationship of the proinflammatory cytokines to myocardial ischemia and dysfunction after uncomplicated coronary revascularization. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;108:626–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knudsen F, Andersen LW. Immunological aspects of cardiopulmonary bypass. J Cardiothorac Anesth. 1990;4:245–58. doi: 10.1016/0888-6296(90)90246-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Butler J, Chong GL, Baigrie RJ, Pillai R, Westaby S, Rocker GM. Cytokine responses to cardiopulmonary bypass with membrane and bubble oxygenation. Ann Thorac Surg. 1992;53:833–8. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(92)91446-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawamura T, Wakusawa R, Okada K, Inada S. Elevation of cytokines during open heart surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass: participation of interleukin 8 and 6 in reperfusion injury. Can J Anaesth. 1993;40:1016–21. doi: 10.1007/BF03009470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Almdahl SM, Waage A, Ivert T, Vaage J. Release of bioactive interleukin 6 but not of tumour necrosis factor-α after elective cardiopulmonary bypass. Perfusion. 1993;8:233–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cruickshank AM, Fraser WD, Burns HJ, Van Damme J, Shenkin A. Response of serum interleukin-6 in patients undergoing elective surgery of varying severity. Clin Sci. 1990;79:161–5. doi: 10.1042/cs0790161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Udelsman R, Holbrook NJ. Endocrine and molecular responses to surgical stress. Curr Prob Surg. 1994;31:653–720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]