Abstract

Bloom's syndrome (BS) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by stunted growth, sun-sensitive erythema and immunodeficiency. Chromosomal abnormalities are often observed. Patients with BS are highly predisposed to cancers. The causative gene for BS has been identified as BLM. The former encodes a protein, which is a homologue of the RecQ DNA helicase family, a family which includes helicases such as Esherichia coli RecQ, yeast Sgs1, and human WRN. WRN is encoded by the gene that when mutated causes Werner's syndrome. The function of BLM in DNA replication and repair has not yet been determined, however. To understand the function of BLM in haematopoietic cells and the cause of immunodeficiency in BS, expression of the BLM gene in various human tissues and haematopoietic cell lines was analysed and the involvement of BLM in immunoglobulin rearrangement examined. In contrast to WRN, BLM was expressed strongly in the testis and thymus. B, T, myelomonocytic and megakaryocytic cell lines also expressed BLM. All of the examined sequences at the junction of the variable (V), diversity (D) and joining (J) regions of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain genes were in-frame, and N-region insertions were also present. The frequency of abnormal rearrangements of the T cell receptor was slightly elevated in the peripheral T cells of patients with BS compared with healthy individuals, whereas a higher frequency of abnormal rearrangements was observed in the cells of patients with ataxia-telangiectasia (A-T). In DND39 cell lines, the induction of sterile transcription, which is required for class switching of immunoglobulin heavy-chain constant genes, was correlated with the induction of the BLM gene. Taking into consideration all these results, BLM may not be directly involved in VDJ recombination, but is apparently involved in the maintenance of the stability of DNA.

Keywords: BLM, expression, B cell differentiation, DNA instability

INTRODUCTION

Bloom's syndrome (BS) is a rare autosomal genetic disorder characterized by lupus-like erythematous telangiectasias of the face, sun-sensitivity, infertility and stunted growth. Upper respiratory infection and gastrointestinal infections are common [1,2]. The syndrome is associated with immunodeficiency of a generalized type and clinically the symptoms range from mild and essentially asymptomatic to severe. Almost all patients with BS have abnormally low concentrations of one or more of the serum immunoglobulins. Chromosomal abnormalities are the hallmarks of the disorder, and a high frequency of sister chromatid exchanges and quadriradial configurations in lymphocytes and fibroblasts is diagnostic of BS.

The gene that when mutated causes BS was identified and designated as BLM [3]. The BLM product is homologous to the RecQ helicase. Several lines of evidence suggest that BLM may be involved in the complex processes of DNA replication and/or repair. Instability of microsatellites and minisatellites in BS has been reported [4]. BLM possesses ATP- and Mg2+-dependent DNA helicase activity that displays 3′-5′ directionality [5]. In addition, BLM has a nuclear localization signal in its C-terminus and is localized in the nucleus [6].

Lymphocyte differentiation in humans occurs via a series of complex steps. Some stages involve DNA breaks and ligations, which might in turn invoke the involvement of DNA repair mechanisms. Specifically, in B cells two gene recombination events occur, namely immunoglobulin gene rearrangement and class switching of the heavy-chain gene constant region. In addition, somatic hypermutation of the immunoglobulin variable genes occurs after antigen stimulation. The molecular mechanisms of these processes, especially class switching and somatic hypermutation, remain speculative [7]. Recently, the role of DNA repair in immunoglobulin recombination and hypermutation has been examined. Phung et al. [8] reported that MSH2-dependent mismatch repair did not cause hypermutation in immunoglobulin variable genes. Several studies in BS cells have shown that recombination and somatic hypermutation of immunoglobulin variable genes is independent of BLM [9–11].

In patients with ataxia-telangiectasia (A-T), a genomic instability syndrome associated with a high frequency of lymphoid malignancies, it has previously been shown that the hybrid antigen-receptor gene formed by interlocus recombination between T cell receptor γ (TCRγ) V segments and TCRβ J segments occurs in peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) at a 50–100-fold higher frequency than normal [12,13]. The increase in frequency of abnormal rearrangements suggests that either ATM, the gene that when mutated causes A-T, is involved in V(D)J recombination in TCR, or that the defect of ATM causes abnormal accessibility of the different antigen receptor loci to the recombinase. The high ratio of chromosomal abnormalities, the high predisposition to lymphomas in BS and the homology of BLM to DNA helicases suggest that BLM may also have a role in VDJ rearrangement, somatic hypermutation and/or class switching. In this study we examine the expression of the BLM gene in various human tissues and cell lines and discuss the involvement of BLM in recombination and class switching.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines

A brother and sister with BS, both Japanese, identified as 96 (HiOk) and 97 (AsOk), respectively, in the BS registry and previously reported in [14], developed B cell lymphoma. A part of the surgically resected lymphomatous tissue was analysed. PBL were prepared by Ficoll–Paque (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-transformed cell lines were established by the addition of the supernatant of the marmoset cell line B95-8. Tissues and PBL from a patient with A-T (T.F.) plus B cell lymphoma were also examined.

Northern blotting

Gene expression in multiple human tissues was examined using MTM (Clonetech, Palo Alto, CA) filters. The probe preparation method and hybridization conditions were reported previously [15]. The probes for Northern blotting of BLM and WRN were prepared by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The primers used were as follows: BLM Bam sense 5′-CCC GGA TCC AGA AAT CTG AAA CAT G-3′ (1983–98), BLM Bam anti-sense 5′-CCC GGA TCC ATT TTC ACC AAA GTA GGC-3′ (3200–3218), WRN S-2 5′-GGA ACA GCA GTC TCA GGA AG–3′ (1446–1465), and WRN A-3 5′-CCG CAT GGT ATG TTC CAC AG–3′ (2601–2620). Chicken β-actin probe was purchased from ONCOR (Gaithersburg, MD).

Determination of expression of BLM by reverse transcriptase-PCR

RNA was extracted by using Isogen (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan) from various human tissues and various haematopoietic cell lines. These cell lines have been described previously [16]. cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of RNA using an oligo dT primer. The primers used for reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR were as follows: BLM sense 5′-GGA TCC TGG TTC CGT CCG C-3′ (34–52), BLM anti-sense 5′-CCT CAG TCA AAT CTA TTT GCT CG-3′ (719–741), β-actin 661S 5′-TGA CGG GGT CAC CCA CAC TGT GCC CAT CTA-3′, and β-actin 661A 5′-CTA GAA GCA TTT GCG GTG GAC GAT GGA GGG-3′. The following PCR conditions were used: 94°C 1 min, 55°C 2 min, 72°C 2 min, with this cycle being repeated 40 times. The PCR product was electrophoresed on 1% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. Thereafter, the DNA was transferred to a nylon membrane and hybridized with 32P-labelled BLM probe.

CDR3 region of the immunoglobulin heavy chain

The complementarity-determining region (CDR) 3 of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene was amplified by RT-PCR using cDNA from PBL. The PCR products were ligated to the T-vector and sequenced. The primer sets used in this experiment are as follows [17]: sense 5′-CTGTCGACACGGCCGTGTATTACTG-3′ (framework 3 of variable region), and anti-sense 5′-AACTGCAGAGGAGACGGTGACC-3′ (J region).

Vγ–Jβ rearrangement

DNA was extracted from PBL using SepaGene (Nippon Gene). Amplification reactions were performed to determine rearrangements between TCRγ and TCRβ Jβ1 segments in a two-step nested PCR protocol described previously [12,13]. 5′ primers were chosen corresponding to conserved sequences within the second exon of the Vγ1 V segments, a highly homologous family of V segments that represent nine of the 14 known Vγ1 V segments. 3′ primers were chosen corresponding to the intron 3′ of Jβ1.6 to allow amplification of rearrangements into any of the six functional Jβ1 segments. Each DNA sample was amplified in 75 μl of PCR reaction mixture with the outer 5′ Vγ primer and the 3′ Jβ primers. The mixture was heated to 95°C for 2.5 min, then subjected to 25 cycles of 0.5 min at 95°C, 0.5 min at 50°C and 6 min at 72°C, followed by 10 min at 72°C after the last cycle. The products of this first reaction (5 μl) were subjected to reamplification with the nested primers in an identical thermal protocol. The specific PCR products were identified by agarose gel electrophoresis and Southern hybridization after transfer onto a nylon membrane with an α-32P-labelled oligonucleotide (internal to the amplification primers) probe. The primer sets used in this experiment are as follows: first PCR: Vγa 5′-TAC ATC CAC TGG TAC CTA CAC CAG-3′; Jβ1a 5′-TTC CCA GCA ACT GAT CAT TG-3′; nested PCR: Vγb 5′-CTA GAA TTC CAG GGT TGT GTT GGA ATC AGG A-3′; Jβ1b 5′-CCA GGA TCC CCC GAG TCA AGA-3′; probe oligonucleotides: Vγc 5′-TCT GGG GTC TAT TAC TGT GCC ACC TGG-3′.

Induction of germ-line Cε transcription in DND39

The DND39 cell line was cultured in RPMI medium with 10% fetal calf serum in the presence of 200 U/ml IL-4 (Genzyme, Cambridge, MA) and 10 μg/ml of anti-CD40 antibody (5C3; PharMingen, San Diego, CA). The DND39 cells were collected at 3, 12 and 48 h. RNA was prepared, and cDNA was synthesized using oligo dT primers. Expression of germ-line Cε transcription was detected by RT-PCR [18]. Germ-line Cε primer: sense (Iε1) 5′-CTG GGA GCT GTC CAG GAA CC-3′, anti-sense (CεRT2) 5′-GCA GCA GCG GGT CAA GG-3′.

RESULTS

Expression of the BLM gene in human tissues

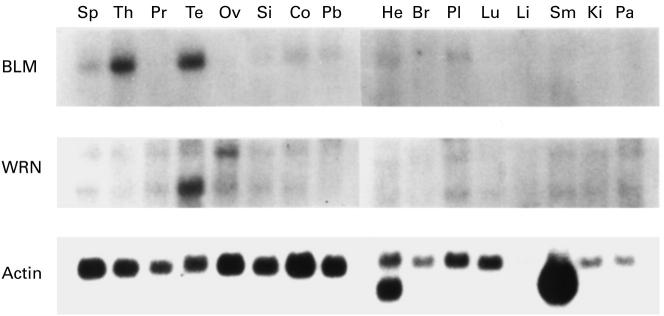

First, we examined the expression of the BLM gene in various human tissues. Northern blotting analysis revealed that the BLM gene was strongly expressed in the thymus and testis. Faint expression of BLM was detected in the spleen and peripheral blood lymphocytes (Fig. 1). On the other hand, the WRN gene was expressed in all the tissues examined, although the strongest expression was noted in the testis. BLM was specifically expressed in the thymus and testis; therefore, we investigated the expression of BLM in various haematopoietic cell lines.

Fig. 1.

Expression of BLM and WRN in various human tissues. Sp, Spleen; Th, thymus; Pr, prostate; Te, testis; Ov, ovary; Si, small intestine; Co, colon; Pb, peripheral blood leucocyte; He, heart; Br, brain; Pl, placenta; Lu, lung; Li, liver; Sm, skeletal muscle; Ki, kidney; Pa, pancreas.

Expression of BLM gene in human haematopoietic cell lines

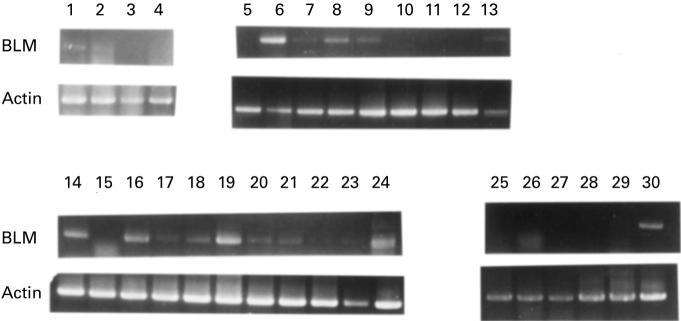

Among the B cell lines tested, the Raji cell line (lane 6) expressed the BLM gene (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Among the T cell lines, both the DND-41 (lane 14) and SKW-3 cells (lane 16) expressed BLM. Myelomonocytic (e.g. NALM-20; lane 19) and megakaryocytic (e.g. MEG1; lane 24) lines also expressed BLM. The EBV-transformed cell lines (lanes 13 and 30) expressed BLM, but the level of expression differed in each (compare lanes 13 and 30). Southern blotting with 32P-labelled BLM fragment showed the band of BLM in all of the examined cell lines (data not shown). These results indicate that the BLM gene was expressed in all haematopoietic cells examined.

Fig. 2.

Expression of BLM in various human haematopoietic cell lines. The number corresponds to the number of the cell line given in Table 1.

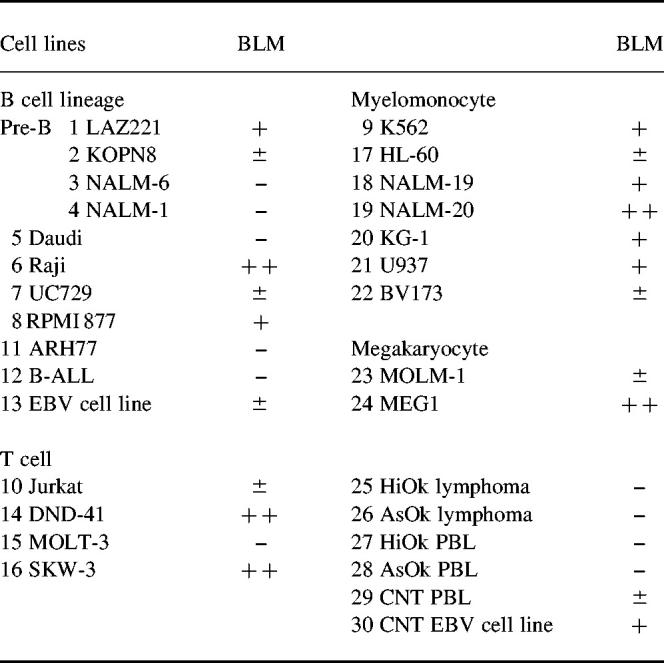

Table 1.

Expression of BLM gene in cell lines and tissues by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

–, Under the detection level of RT-PCR by ethidium bromide staining. Southern hybridization with labelled probe detected the expression of BLM in all of the examined cell lines and PBL.

CDR3 region of the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene in the PBL of patients with BS

Since the BLM gene is expressed in B lymphocytes, we examined the involvement of BLM in the recombination of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene. All the recombinations in the CDR3 region of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene were in-frame in PBL prepared from both HiOk and AsOk (data not shown). N-region insertion was also detected. No abnormal rearrangements were detected in any of the clones examined (data not shown).

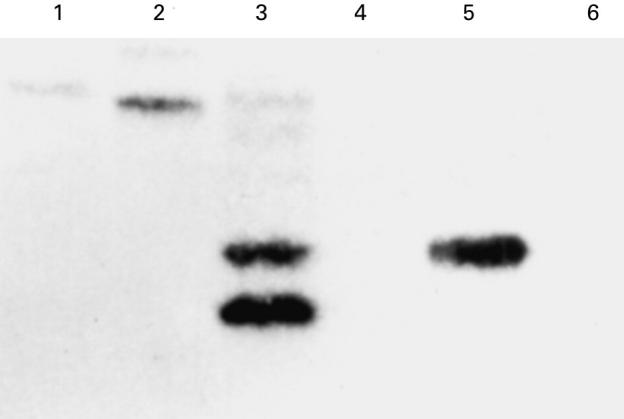

Abnormal rearrangement in TCR loci

BS cells show genomic instability. Detection of abnormal rearrangement in the TCR loci indicates genomic instability. In A-T PBL (lane 3 in Fig. 3), hybrid TCR genes formed by interlocus recombination between TCRγ V segments and TCRβ J segments were detected as previously reported. The PBL of neither of the BS patients (lanes 1 and 2) showed the bands as prominently as those of the A-T patient. A few bands were amplified and hybridized with a TCRγ oligonucleotide probe, while control PBL did not show any bands (lane 6). Cells from the B-cell lymphoma taken from the BS patients showed either one band or no bands at all (lanes 4 or 5). Both 1 μg and 5 μg of PBL DNA showed similar patterns (data not shown). These results suggest that T cells prepared from patients with BS have increased DNA instability in comparison with those from controls.

Fig. 3.

Southern blot analysis of amplified T cell receptor (TCR) Vγ–Jβ hybrid genes from genomic PBL DNA (1 μg) from a control individual, two Bloom's syndrome (BS) patients and an ataxia-telangiectasia (A-T) patient. Vγc oligonucleotide was used as the hybridization probe. Lane 1, HiOk PBL; lane 2; AsOk PBL; lane 3, A-T PBL; lane 4, HiOk lymphoma; lane 5, AsOk lymphoma; lane 6, control PBL.

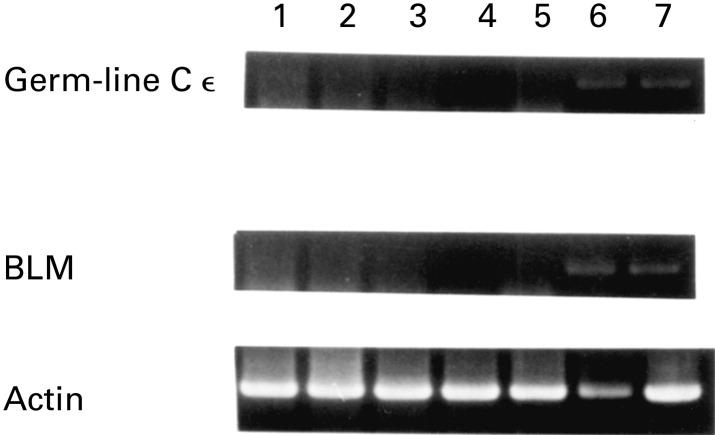

Correlation between BLM expression and germ-line transcription in the DND-39 cell line

The possibility of the involvement of BLM in immunoglobulin class switching was examined. Incubation for 48 h in the presence of IL-4 or IL-4 + CD40 antibody induced ε germ-line transcription in DND-39 cell lines (Fig. 4). Expression of the BLM gene was correlated with ε germ-line transcription (lanes 6 and 7).

Fig. 4.

Induction of germ-line Cε and BLM in DND-39 cells. Lane 1, no stimulation; lane 2, cultured with IL-4 for 3 h; lane 3, cultured with IL-4 and CD40 for 3 h; lane 4, cultured with IL-4 for 12 h; lane 5, cultured with IL-4 and CD40 for 12 h; lane 6, cultured with IL-4 for 48 h; lane 7, cultured with IL-4 and CD40 for 48 h.

DISCUSSION

Almost all patients with BS have abnormally low concentrations of one or more of the plasma immunoglobulins and fail to show delayed hypersensitivity. The mechanisms of immunodeficiency remain to be elucidated. The identification of the DNA helicase function of BLM may help clarify the relationship between lymphocyte differentiation and the complex proteins of DNA repair. The involvement of BLM in DNA repair has not yet been determined. Werner's syndrome is characterized by premature ageing and the gene that when mutated causes Werner's syndrome is WRN, which is homologous to BLM. However, immunodeficiency is not a characteristic clinical feature of Werner's syndrome. BLM is preferentially expressed in the thymus and testis while WRN is ubiquitously expressed, with strongest expression in the testis. The difference in the expression pattern between BLM and WRN might explain the clinical features of immunodeficiency in BS. BLM expression was detected in all of the examined haematopoietic cell lines, including myelomonocytes. Although the function of myelomonocytes in BS has not been determined yet, this might explain why some BS patients with normal serum immunoglobulin levels also have an increased susceptibility to infection.

Abnormal T cell rearrangements were observed at an increased frequency in the PBL of patients with BS compared with control individuals. However, the frequency of abnormal rearrangement in the PBL of the patients with BS was lower than that in the PBL of patients with A-T. Consistent with previous reports [9–11], the sequences of the CDR3 region VDJ rearrangement in the peripheral B cells of patients with BS were in-frame and the N-region insertion was also present. These results suggest that the DNA helicase activity of BLM is not directly involved in VDJ recombination. Both T and B cells utilize the same machinery for VDJ recombination. Cells of patients with BS have a normal immunoglobulin VDJ recombination, therefore it is unlikely that the increased frequency of abnormal T cell rearrangement in BS is caused by an abnormal catalytic function of the recombinase. Another explanation might be abnormal accessibility of the different antigen receptor loci to the recombinase in BS cells. The increased frequency of abnormal T cell rearrangement suggests that BLM is involved in the maintenance of DNA stability.

In class switching recombination, germ-line transcripts are expressed prior to the recombination. IL-4 induces ε germ-line transcription in DND-39 cell lines and it also induces the BLM gene. However, the results shown in Fig. 4 are only preliminary, and might merely reflect coincidental expression. To address this issue, the binding sites in the BLM promoter region must be elucidated. Recently, Sun et al. reported that BLM helicase efficiently unwinds G4 DNA [19] and, as G4 DNA is a consensus repeat of immunoglobulin switch regions, this finding is intriguing. Further experiments are required to determine the involvement of BLM in class switching.

REFERENCES

- 1.German J. Bloom syndrome: a mendelian protototype of somatic mutational disease. Medicine. 1993;72:393–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.German J. Bloom's syndrome. Dermatol Clin. 1995;13:7–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellis NA, Groden J, Ye TZ, Straughen J, Lennon DJ, Ciocci S, Proytcheva M, German J. The Bloom's syndrome gene product is homologous to RecQ helicases. Cell. 1995;83:655–66. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90105-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foucault F, Buard J, Praz F, Jaulin C, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Vergnaud G, Amor-Gueret M. Stability of microsatellites and minisatellites in Bloom syndrome of genetic instability. Mutat Res. 1996;362:227–36. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(95)00047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karow JK, Chakraverty RK, Hickson ID. The Bloom's syndrome gene product is a 3′-5′ DNA helicase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:30611–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.30611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaneko H, Orii KO, Matsui E, et al. BLM (the causative gene of Bloom syndrome) protein translocation into the nucleus by a nuclear localization signal. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;240:348–53. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manis JP, Gu Y, Lansford R, Sonoda E, Ferrini R, Davidson L, Rajewsky K, Alt FW. Ku 70 is required for late B cell development and immunoglobulin heavy chain class switching. J Exp Med. 1998;187:2081–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.12.2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phung QH, Winter DB, Cranston A, Tarone RE, Bohr VA, Fishel R, Gearhart PJ. Increased hypermutation at G and C nucleopetides in immunoglobulin variable genes from mice deficient in the MSH2 mismatch repair protein. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1745–51. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.11.1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsieh CH, Arlett CF, Lieber MR. V(D)J recombination in Ataxia Telangiectasia, Bloom's syndrome, and a DNA ligase I-associated immunodeficiency disorder. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:20105–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petrini JH, Donovan JW, Dimare C, Weaver DT. Normal V(D)J coding junction in DNA ligase I deficiency syndromes. J Immunol. 1994;152:176–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sack SZ, Liu Y, German J, Green NS. Somatic hypermutation of immunoglobulin genes is independent of the Bloom's syndrome DNA helicase. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;112:248–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00575.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lipkowitz S, Stern MH, Kirsch IR. Hybrid T cell receptor genes formed by interlocus recombination in normal and ataxia-telangiectasia lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1990;172:409–18. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.2.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lipkowitz S, Garry VF, Kirsch IR. Interlocus V-J recombination measures genomic instability in agriculture workers at risk for lymphoid malignancies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5301–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaneko H, Inoue R, Yamada Y, et al. Microsatellite instability in B-cell lymphoma originating from Bloom syndrome. Int J Canc. 1996;69:480–3. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19961220)69:6<480::AID-IJC11>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu C-E, Oshima J, Fu Y-H, et al. Positional cloning of the Werner's syndrome gene. Science. 1996;272:258–62. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5259.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaneko H, Ariyasu T, Inoue R, et al. Expression of Pax5 gene in human hematopoietic cells and tissues: comparison with immunodeficient donors. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;111:339–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00509.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamada M, Wasserman R, Reichard BA, Shane S, Caton AJ, Rovera G. Preferential utilization of specific immunoglobulin heavy chain diversity and joining segments in adult human peripheral blood B lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1991;173:395–407. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.2.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ichiki T, Takahashi W, Watanabe T. The effect of cytokines and mitogens on the induction of Cε germline transcripts in a human Burkitt lymphoma B cell line. Int Immunol. 1992;4:747–54. doi: 10.1093/intimm/4.7.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun H, Karow JK, Hickson ID, Maizels N. The Bloom's syndrome helicase unwinds G4 DNA. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:27587–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]