Abstract

This study investigated the effect of maternal Onchocerca volvulus infection on humoral and cellular responsiveness in newborn children and their mothers. Onchocerca volvulus-specific IgG isotypes and IgE were significantly elevated in infected mothers and their infants. One year post partum, O. volvulus-specific IgG4 was strongly reduced in children of infected mothers, while IgG1 responses weakened only slightly. Umbilical cord mononuclear blood cells (UCBC) and peripheral blood cells (PBMC) from mothers proliferated in response to phytohaemagglutinin (PHA), concanavalin A (Con A), and the bacterial antigens streptolysin-O (SL-O) or purified protein derivative (PPD). UCBC from neonates born to O. volvulus-infected mothers responded lower (P < 0.01) to Con A (at 5 μg/ml), PPD (at 10 and 50 μg/ml) and O. volvulus-derived antigens (OvAg) (at 35 μg/ml), and in parallel, a diminished cellular reactivity (P < 0.01) by PBMC was observed to OvAg in mothers positive for O. volvulus. Several Th1-type (IL-2, IL-12, interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α)) and Th2-type (IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, IL-13) cytokines were secreted by UCBC and PBMC in response to OvAg, bacterial SL-O and PHA. OvAg did not stimulate IL-2 and none of the mitogens or antigens induced production of IL-4 in neonates. In response to OvAg, substantially elevated (P < 0.01) amounts of IFN-γ were produced by UCBC from newborns of O. volvulus-infected mothers. UCBC secreted low levels of IL-5 and IL-13, while higher amounts of IL-10 were found (P < 0.01) in newborns from onchocerciasis-free mothers. In conclusion, maternal O. volvulus-infection will sensitize in utero parasite-specific cellular immune responsiveness in neonates and activate OvAg-specific production of several Th1- and Th2-type cytokines.

Keywords: onchocerciasis, neonatal immunity, antibody production, cellular responses, cytokines

INTRODUCTION

In onchocerciasis and lymphatic filariasis the manifestation of disease varies from asymptomatic infection to severe pathology [1], and filarial infection in indigenous populations often persists without evident clinical disease [2]. The lower expression of pathology in endemic populations, despite high infection intensities, has been attributed to prenatal or neonatal exposure to parasites or parasite antigens which may have induced parasite-specific immunotolerance [2–6]. During pregnancy, parasite-specific antibodies, antigens and even entire parasites may pass transplacentally from the mother into the foetus [7]. In filaria-infected mothers, transplacental migration of microfilariae (mf) has been reported for Onchocerca volvulus, Mansonella perstans, and Wuchereria bancrofti [8–11], and such exposure to parasite antigens may prime and bias immunocompetence in offspring. Indeed, maternal filarial infection, and in utero exposure to filarial antigens, has been considered to influence later in life infection intensity and cellular immunity in offspring [12, 13]. Appropriate and unbiased immunocompetence upon parasite challenge is considered to be the critical determinant for effective control of infection [1, 14–16]. In onchocerciasis, deviated expression of immunity is associated with chronic infection and characterized by predominant Th2-type responses, while Th1-type responses are found in individuals exposed to infection presenting no clinical sign of disease [17–19]. Induction of immune responses with a preferential Th2 pattern has been demonstrated upon tolerance induction in newborns [20], and neonatally induced specific immune responses will persist upon secondary antigen contact later in life [21]. The particular susceptibility to tolerogenic signals during prenatal and neonatal life, and the exposure to parasite antigens at this stage of maturation, may prime for specific immunotolerance and facilitate parasite persistence. During the prenatal and neonatal period the developing foetal immune system learns to discriminate self from non-self by developing tolerance to antigens it encounters [22]; consequently, maternal infection has been considered a risk factor for increased susceptibility and facilitated parasite persistence in offspring [3, 5, 6]. Prenatal allergic sensitization to helminth antigens may also contribute to inappropriate immune responsiveness and disease manifestation [23].

The present study was aimed at determining whether prenatal exposure to O. volvulus microfilariae and filarial antigens in newborns will prime for O. volvulus-specific T cell responses, and if prenatal priming does occur will it lead to allergic sensitization or diversion of T cell responses into the Th2 pathway. Our results add evidence that indeed maternal O. volvulus infection will sensitize in utero parasite-specific cellular responsiveness in neonates and activate antigen-specific production of several Th1- and Th2-type cytokines.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Location of study and study population

This study was conducted in central Togo in West Africa, within the vector controlled area of the Onchocerciasis Control Programme (OCP), where the risk of infection with O. volvulus still remains high [24, 25]. Onchocerca volvulus-infected mothers and their newborns originated from selected villages where onchocerciasis was mesoendemic. Authorization for this study was given by the Togolese Ministry of Health and informed consent was obtained from all mothers before enrolling in this study. Serum samples and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were obtained from mothers, and heparinized umbilical cord blood samples (30–50 ml) were collected from full-term newborns at delivery. In all pregnant mothers the density of O. volvulus microfilariae was determined in skin biopsies taken from the right and left hip [14]. From pregnant mothers stool samples were collected and concurrent intestinal helminth or protozoan infections were determined by standard parasitological methodology. All mothers included in this study were negative for HIV-1 and -2 as determined by ELISA (Enzygnost; Behring, Marburg, Germany).

Onchocerca volvulus antigen-specific ELISA

Paired cord and maternal blood samples were obtained and the levels of O. volvulus antigen-specific (OvAg-specific) total IgG and IgG isotypes were determined by ELISA [14, 26]. For the determination of O. volvulus-specific IgE in mothers and their babies, sera were preabsorbed with Sepharose Protein-G (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). Briefly, equal volumes (50 μl) of sera and Sepharose Protein-G (5 mg/ml) were incubated overnight at 4°C on a shaker, then centrifuged (15000 g, 5 min) and the sera used at a final dilution of 1:40. Microtitre plates (Nunc Maxisorb, Wiesbaden, Germany) were coated with O. volvulus crude antigen (OvAg 5 μg/ml) overnight, non-specific binding capacity of wells was blocked with PBS containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and serum samples and reference control sera were added in duplicate to OvAg-coated wells and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. After washing (PBS–0.05% Tween 20), biotinylated anti-human IgE MoAb (BIOZOL, Eching, Germany) was added for 45 min at room temperature. Plates were then washed (as above) and streptavidin, conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) was added for 30 min at room temperature. Following extensive washes (×12), specific binding was visualized by addition of TMB substrate, the reaction was then stopped after 15 min, and the optical density (OD) was determined at 405 nm. Preparation of O. volvulus adult worm-derived antigen (OvAg) was effected as described previously [27, 28].

Isolation of umbilical cord blood mononuclear cells and cell culture experiments

Heparinized venous or cord blood was collected from mothers and newborns, and PBMC or umbilical cord blood cells (UCBC) were isolated by Ficoll–Paque (Pharmacia) density gradient centrifugation. Cell culture experiments were conducted as previously described by Soboslay et al. [14, 15]. Briefly, PBMC were adjusted to 1 × 107/ml in RPMI (Gibco, Eggenstein, Germany) supplemented with 25 mm HEPES buffer, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 0.25 μg/ml amphotericin B; they were then immediately used to stimulate cytokine transcription and cytokine secretion.

For purposes of depletion of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells, PBMC (at 1 × 107/ml) were suspended with anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 antibody-coated immunomagnetic beads (Dynal; Dynabeads M-450/CD4 or M-450/CD8) at a bead:cell ratio of 5:1, incubated at 2–4°C for 60 min with gentle tilting and rosetted CD4+ or CD8+ cells depleted from whole UCBC with a magnetic particle concentrator (MPC) as recommended by the manufacturer. Viability of depleted cell populations was always > 95%. For purposes of proliferation assays, isolated PBMC as well as CD4+ or CD8+ depleted UCBC were seeded at 1 × 105 cells/well in sterile round-bottomed 96-well microtitre plates (Costar, Cambridge, MA). Cells were suspended in RPMI (as above) containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), and kept in 5% CO2 at 37°C and saturated humidity. For purposes of mitogenic stimulation with phytohaemagglutinin (PHA; 1:100; Gibco) or concanavalin A (Con A; 0.5–5 μg/ml; Gibco), and of antigenic stimulation with OvAg (0.35–35 μg/ml), streptolysin-O (SL-O; 1:50–500; Difco, Augsburg, Germany) and mycobacterial purified protein derivative (PPD; 20–100 μg/ml; Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany), cultures were maintained for 3 and 5 days, respectively. For the last 18 h 1 μCi of 3H-thymidine was added; cells were then harvested on glassfibre filters (Skatron, Lier, Norway) and the incorporated radioactivity was determined by scintillation spectroscopy (Beta Plate; LKB-Pharmacia). Data are indicated as mean values of triplicate cultures in ct/min minus baseline stimulation.

Determination of cytokine production

Freshly isolated PBMC and UCBC were cultured at a concentration of 3.7 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI (as above) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS, in the presence of either O. volvulus-derived antigen (3.5 μg/ml) or PHA (1:100; Gibco) or SL-O (1:50; Difco) in 5% CO2 at 37°C and saturated humidity. Cell culture supernatants were collected after 48 h and stored in liquid nitrogen. Cytokine secretion by stimulated PBMC was quantified by sandwich ELISA using cytokine-specific monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies for IL-2, IL-5, IL-10, IL-13 and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α; Pharmingen, Hamburg, Germany), and for IL-4, IL-12 and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ; BioSource, Ratingen, Germany) as recommended by the manufacturer, and as previously described [15].

Statistical analysis

Results are indicated as mean values ± s.e.m. of different groups. Data were tested for normality and the variance of two data groups. Statistical analyses were performed by either Student's t-test or the Mann–Whitney test.

RESULTS

The study population

Prevalence of O. volvulus infection in mothers (n = 113) was 44% (mean), while 75% (aggregate) of the study group were infected with protozoan or helminth parasites. One-third (30%) of the mothers were singly infected, in 27% of the cases two parasites were detected, a triple infection was diagnosed in 15% of the mothers and 4% harboured a quadruplicate helminth and protozoan infection. Hookworm (42%), amoebiasis (30%), strongyloidiasis (17%), mansonelliasis (12%), Giardia lamblia (9%), Trichomonas intestinalis(19%), Ascaris lumbricoides(4%) and Schistosoma mansoni(1%) were found. The mean age of mothers was 22 years (range 17–40 years) and the reported average number of births per mother was 3.2 (range 1–10).

Parasite-specific immunoglobulins in mothers, neonates and children

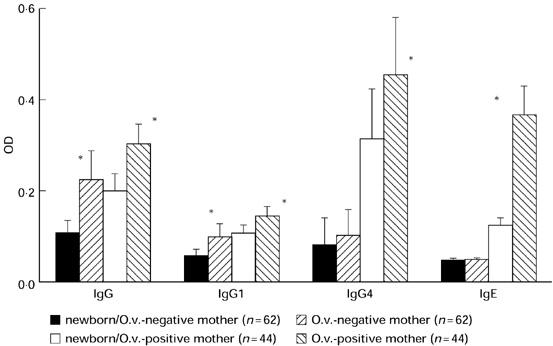

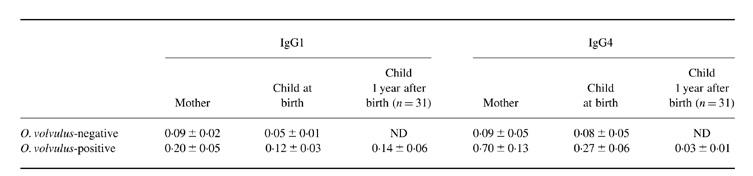

In O. volvulus-infected mothers and their babies, parasite-specific IgG4 and IgE were significantly higher than in non-infected mothers and their children (Fig. 1). Onchocerca volvulus-specific IgG subclasses were always higher in mothers than in their offspring, with IgG4 showing strongest reactivity in infected mothers and their offspring, and all IgG isotypes were positively correlated in mothers and their babies (data not shown). In babies born to O. volvulus microfilariae-positive mothers OvAg-specific IgE reactivity was twice as high as in babies born to non-infected mothers, providing clear evidence that prenatal sensitization had occurred in these children. In addition, paired cord and maternal immunoglobulin isotype reactivity to OvAg were determined at birth and, in O. volvulus-infected mother–child pairs, 1 year post partum(Table 1). In O. volvulus-infected mother–child pairs examined 1 year post partum, O. volvulus-specific IgG4 reactivity was strongly reduced in babies at 12 months after birth, while IgG1 responses weakened only slightly.

Fig. 1.

Onchocerca volvulus-specific IgG isotype and IgE reactivity (optical density (OD) ± s.d.) in newborns and their O. volvulus microfilariae-positive or -negative mothers. Determination of IgG isotypes as well as IgE-specific reactivity to O. volvulus-derived antigens was performed as described in Subjects and Methods. (*P < 0.05)

Table 1.

Determination of Onchocerca volvulus-specific IgG1 and IgG4 reactivity in O. volvulus-infected (n = 44) and non-infected mothers and their children (optical density (OD) at 405 nm)

ND, Not determined.

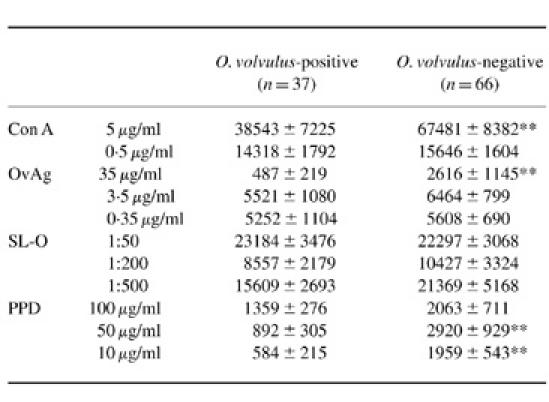

Cellular reactivity to mitogens and antigens in neonates

UCBC from mothers with or without O. volvulus infection proliferated after mitogenic stimulation with PHA and Con A, and after stimulation with bacterial (SL-O, PPD) and O. volvulus-derived antigens (Table 2). The background proliferation of unstimulated cells from babies born to infected and non-infected mothers was compared and was similar in both groups, indicating that proliferative responses were not raised due to presence of a maternal infection (Table 2). Pronounced cellular responses were measured when UCBC were stimulated with PHA, Con A and SL-O, while cellular reactivity remained low when stimulated with mycobacterial PPD or Echinoccocus multilocularis-derived antigens (not shown). Reactivity to the T cell mitogen Con A (at 5 μg/ml) was lower (P < 0.01) in UCBC from O. volvulus-infected mothers, but lower Con A concentrations (0.5 μg/ml) did not induce such differences (Table 2). At all antigen concentrations tested reactivity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis-derived antigens (PPD) was lower in UCBC from O. volvulus-infected mothers (Table 2); however, pronounced cellular proliferation of UCBC was induced by the bacteria-derived SL-O with no differences between the study groups (Table 2). Low cellular reactivity of UCBC to OvAg was measured at antigen concentrations of 35 μg/ml, but responsiveness to OvAg increased with decreasing antigen concentrations and was highest in both groups at OvAg concentrations of 3.5 and 0.35 μg/ml. Proliferative reactivity to OvAg (at 35 μg/ml) was significantly reduced (P < 0.01) in newborns of O. volvulus-infected mothers, but no such differences were observed when cells were stimulated with lower antigen concentrations (Table 2). Depletion of CD4+ or CD8+ from UCBC drastically reduced cellular responsiveness to mitogens (PHA, Con A) and antigens (SL-O, OvAg) (data not shown).

Table 2.

Cellular reactivity of umbilical cord mononuclear cells (UCBC) in neonates born to Onchocerca volvulus microfilariae- positive and negative mothers. UCBC were stimulated with concanavalin A (Con A), O. volvulus-derived antigens (OvAg), Streptococcus pyogenes-derived streptolysin-O (SL-O) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis-derived purified protein derivate (PPD). Values are indicated as mean ct/min ± s.e.m. of triplicate cultures.

UCBC background proliferation for mitogen stimulation assays (Con A): newborns from O. volvulus microfilariae mf-positive mothers 2307 ± 236 ct/min (mean ± s.e.m.) (range 30–8587 ct/min; median 1670 ct/min); newborns from O. volvulus mf-negative mothers 2650 ± 498 ct/min (range 29–7312 ct/min; median 1384 ct/min). Background proliferation for antigen stimulation assays (OvAg, SL-O, PPD): newborns from mf-positive mothers 2957 ± 234 ct/min (range 44–13 921 ct/min, median 2173 ct/min); newborns from mf-negative mothers 2178 ± 214 ct/min (range 43–12 126 ct/min, median 1090 ct/min).

**P < 0.01.

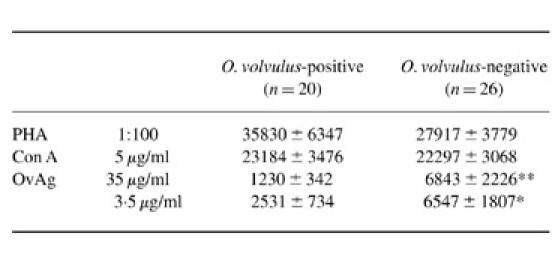

Cellular reactivity to mitogens and antigens in O. volvulus-infected and non-infected mothers

PBMC isolated from O. volvulus microfilariae-positive and mf-negative mothers proliferated in response to mitogenic (PHA, Con A) as well as OvAg-specific stimulation (Table 3). A similar magnitude of cellular responsiveness to PHA and Con A was observed in mf-positive and mf-negative mothers, but cellular responses to OvAg (at 3.5 and 35 μg/ml) were significantly reduced in mf-positive women.

Table 3.

Cellular reactivity of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from Onchocerca volvulus microfilariae-positive and mf-negative mothers. PBMC were stimulated with phytohaemagglutinin (PHA), concanavalin A (Con A) and O. volvulus-derived antigens (OvAg)

Background proliferation in mitogen (PHA and Con A) stimulation assays: O. volvulus mf-positive mothers 1419 ± 130 ct/min (mean ± s.e.m.) (range 787–2796 ct/min, median 1184 ct/min); O. volvulus mf-negative mothers 1530 ± 288 ct/min (range 684–8288 ct/min, median 1190 ct/min). Background proliferation in antigen (OvAg) stimulation assays: mf-positive mothers 1553 ± 349 ct/min (range 169–9804 ct/min, median 775 ct/min); mf-negative mothers 1832 ± 301 ct/min (range 113–7379 ct/min, median 1531 ct/min).

** P < 0.01; *P < 0.05.

Cellular production of cytokines in neonates

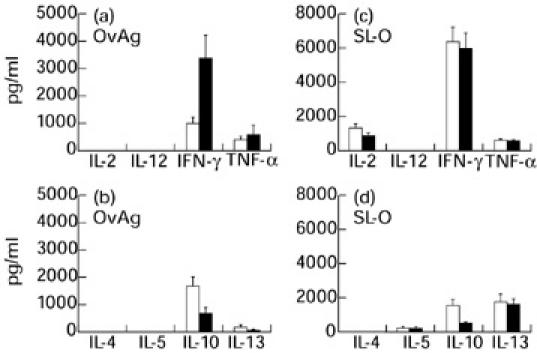

Neonate cytokine production by UCBC from O. volvulus-infected or non-infected mothers is shown in Fig. 2. In response to OvAg, PHA and SL-O production of several Th1 as well as Th2 type cytokines was measurable in cell culture supernatants, but none of the mitogens or antigens used in this study induced measurable production of IL-4 or IL-12. Spontaneous production of IL-10 in babies born to non-infected mothers was three times higher than the IL-10 production from babies born to infected mothers and more of them (41/54 versus 18/39) produce spontaneous IL-10 (Fig. 2, legend). In contrast, spontaneous TNF-α production was nearly twice as high in babies from infected mothers, and 29/34 versus 36/54 babies produced TNF-α (Fig. 2, legend).

Fig. 2.

Secretion of Th1-type (IL-2, IL-12, IFN-γ and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α)) and Th2-type (IL-4, IL-5, IL-10 and IL-13) cytokines by umbilical cord mononuclear blood cells (UCBC) from neonates born to Onchocerca volvulus-positive (▪) or negative mothers (□) in response to O. volvulus-derived antigens (OvAg 3.5 μg/ml) (a,b), and in response to Streptococcus pyogenes-derived streptolysin-O (SL-O; 1:50) (c,d). The results represent net cytokine production with spontaneous (baseline) cytokine production subtracted. Spontaneous cytokine production in the absence of antigen in babies from O. volvulus-negative (Neg) and babies from O. volvulus-positive (Pos) mothers was: for IL-2, detected in one out of 93 babies; for IL-5, detected in two out of 54 Neg (54 ± 55 pg/ml) and in four out of 31 Pos (21 ± 12 pg/ml); for IL-10, 920 ± 310 pg/ml in Neg (n = 54) and 358 ± 131 pg/ml in Pos (n = 39); for IL-13, detected in three of 54 Neg and in two of 31 Pos; for IFN-γ, 260 ± 122 pg/ml for Neg (n = 54) and 370 ± 140 pg/ml for Pos (n = 31); for TNF-α, 516 ± 159 pg/ml in 36 out of 54 Neg and 914 ± 211 pg/ml in 29/43 Pos.

Th1-type cytokines

Neonatal cellular production of IL-2 was detectable when UCBC were stimulated with PHA or SL-O, while O. volvulus-derived antigen did not induce IL-2 (Fig. 2a,c). In response to the mitogen PHA (not shown) and bacterial SL-O, substantial amounts of IFN-γ were secreted by UCBC, there being no differences between newborns from O. volvulus-infected or non-infected mothers (Fig. 2c). However, in response to OvAg substantially elevated amounts of IFN-γ were produced by UCBC from newborns of O. volvulus-infected mothers compared with those from non-infected mothers (Fig. 2a). TNF-α was produced by UCBC in response to mitogen PHA (not shown) as well as to bacterial SL-O and O. volvulus-derived antigens, with TNF-α being similarly high in newborns from O. volvulus-infected or non-infected mothers (Fig. 2a,c).

Th2-type cytokines

UCBC from newborns produced several Th2-type cytokines, i.e. IL-5, IL-10 and IL-13, in response to mitogenic or antigenic stimulation. Low levels of IL-5 were detected when UCBC were stimulated with OvAg in newborns from O. volvulus-infected and non-infected mothers (Fig. 2b), with clearly more IL-5 being produced by UCBC following stimulation with the mitogen PHA (not shown) or bacterial SL-O (Fig. 2d). No statistical differences in IL-5 production were observed between newborns from O. volvulus-infected and non-infected mothers. However, a significantly greater amount of IL-10 was secreted by UCBC in newborns from O. volvulus infection-free mothers in response to the mitogen PHA (not shown) as well as to bacterial SL-O and to O. volvulus-derived antigens (Fig. 2b,d). Umbilical cord blood cells from newborns secreted IL-13 in response to mitogenic and antigenic stimulation. Low levels of IL-13 were induced by OvAg in contrast to PHA or SL-O stimulation, after which UCBC secreted higher amounts of IL-13. No statistical differences were found between cellular IL-13 production by UCBC in newborns from O. volvulus-infected and non-infected mothers.

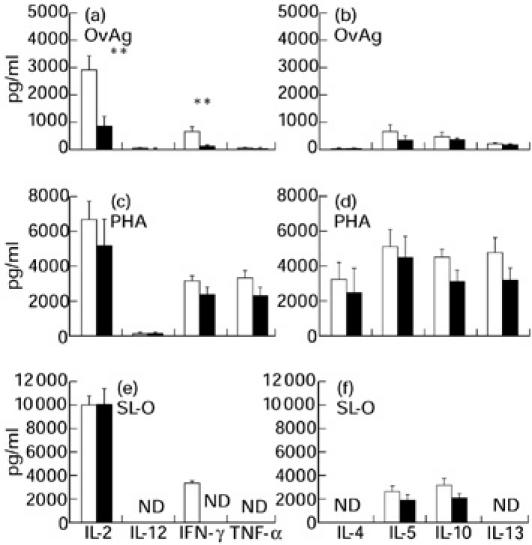

Cellular production of cytokines in mothers

Cytokine production by PBMC from O. volvulus-infected and non-infected mothers is shown in Fig. 3. PBMC from mothers secreted IL-2 spontaneously, and higher amounts (P > 0.05) were detected in O. volvulus-negative mothers (legend to Fig. 3). In response to OvAg, more IL-2 and IFN-γ (P < 0.01) were produced by PBMC from O. volvulus-negative mothers. In response to the mitogen PHA, cells from mothers produced substantial amounts of IL-2 and IL-4, while no mitogen-induced IL-4 was detectable in UCBC cultures. Secretion of IL-12 by PBMC in response to OvAg was low, detected only in 3/22 mf-positive and 11/14 mf-negative mothers. Production of IL-5 in response to OvAg was twice as high in O. volvulus-negative mothers than in those positive for microfilariae of O. volvulus.

Fig. 3.

Secretion of Th1-type (IL-2, IL-12, IFN-γ and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α)) and Th2-type (IL-4, IL-5, IL-10 and IL-13) cytokines by peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from Onchocerca volvulus-positive (▪) and negative mothers (□) in response to O. volvulus-derived antigens (OvAg, 3.5 μg/ml) (a,b), phytohaemagglutinin (PHA, 1:100) (c,d) and Streptococcus pyogenes-derived streptolysin-O (SL-O, 1:50) (e,f) (**P < 0.01). The results represent net cytokine production with spontaneous (baseline) cytokine production subtracted. Spontaneous cytokine production in the absence of antigen in O. volvulus-negative (Neg) and O. volvulus-positive (Pos) mothers was: for IL-2, 1218 ± 230 pg/ml in Neg (n = 23) and 368 ± 42 pg/ml in Pos (n = 25); for IL-4, detected in two out of 14 Neg (3 ± 2 pg/ml) versus 3/20 Pos (3 ± 2 pg/ml); for IL-5, 32 ± 20 pg/ml in Neg (n = 28) and 51 ± 25 pg/ml in Pos (n = 22); for IL-10, 558 ± 103 pg/ml in Neg (n = 26) and 610 ± 96 pg/ml in Pos (n = 23); for IL-12, 371 ± 54 pg/ml in Neg (n = 14) and 503 ± 92 pg/ml in Pos (22); for IL-13, 4 ± 3 pg/ml detected in 2/17 Neg and 20 ± 10 pg/ml in 2/20 Pos; for IFN-γ, 118 ± 50 pg/ml for Neg (n = 26) and 60 ± 21 pg/ml for Pos (n = 24); for TNF-α, 441 ± 144 pg/ml for Neg (n = 17) and 114 ± 28 pg/ml for Pos (n = 20). ND, Not determined.

DISCUSSION

Maternal helminth infections were found to be a risk factor for offspring, causing increased infection susceptibility, higher parasite densities after exposure in later life and impaired parasite-specific immunocompetence [3–5]. The presence of O. volvulus microfilariae in fetal tissues [10] and blood-circulating microfilariae in newborns from W. bancrofti-infected mothers [11] indicated that prenatal sensitization may occur in children born to filaria-infected mothers. As a consequence of in utero exposure to foreign (parasite-derived) antigens, progeny could become tolerized by negative selection of antigen-specific T cells [22], sensitized for allergic responsiveness [23], or deviated in their T cell reactivity [29].

Prenatal sensitization will induce parasite-specific IgM and IgE production in newborns, but fetal IgG subclass production remains difficult to determine due to passage of maternal IgG across the placenta [7, 30]. In newborns from infected mothers, O. volvulus-specific IgG isotypes and IgE were prominent at birth, cord and maternal IgG levels being directly correlated, and in babies born to O. volvulus microfilariae-positive mothers OvAg-specific IgE reactivity was twice as high as in babies born to non-infected mothers, providing clear evidence that prenatal sensitization had occurred in these children. Furthermore, isotype reactivity in neonates changed differentially during the first year of life. IgG4 responses were reduced to low levels, but children's IgG1 remained elevated. Such differential development of antibody isotypes may reflect a marked decrease in maternal IgG4, while post-natal IgG1 production may have started after the first 6 months of life. All children in this study were breast fed during the first year, and therefore postnatal IgG1 reactivity could be due to immunoglobulins contained in breast milk, or else the continuous transfer of O. volvulus antigens by breast feeding [31] may have induced early specific IgG1 production in offspring.

All mothers of this study originated from rural villages in central Togo where onchocerciasis is hyper- to mesoendemic [25], meaning that all mothers were exposed to O. volvulus infection, and such exposure being confirmed by their OvAg-specific cellular reactivity. The higher responsiveness to OvAg in O. volvulus mf-free mothers is in accordance with previous observations, which showed that individuals exposed to O. volvulus but without mf or clinical disease have higher cellular responses to OvAg than mf-positive individuals [17–19]. Therefore, OvAg-specific responsiveness in newborns of onchocerciasis-free mothers could be due to the leakage across the placenta of low or ultra low levels of O. volvulus-derived antigens, possibly complexed with circulating antibodies, which may provide the stimulus for T cell priming. Furthermore, ultra low levels of antigen that cross the placenta are in the range that is preferentially stimulatory to Th2 cells [32–34], and this could be the reason for enhanced OvAg-specific Th2-like IL-10 and the diminished Th1-type IFN-γ production in newborns from non-infected mothers. The cell-mediated immunocompetence of neonates, compared with adults, has been considered for some time as immature and intrinsically deficient as regards becoming appropriately activated upon antigen encounter [35–37]. Recent studies have shown that neonatal T cells responses, like those in adults, can be appropriately activated, tolerized, or switched to Th1 or Th2 responses by such parameters as dosage of antigen, type of antigen presentation, and the mode of immunization [20, 29, 38]. Interestingly, neonatal T cells require much lower doses of antigen than adult T cells to become activated, tolerized, or biased towards a Th2 phenotype [38]. From our observations we conclude that filaria-specific cellular hyporesponsiveness in progeny may be manifested with an increasing parasite load, i.e. with repeated post-natal infections and continuous accumulation of parasites, cellular anergy may develop and facilitate parasite persistence as well as predispose for chronic O. volvulus infection. Indeed, previous studies support this notion, since children born to filaria-infected mothers were found to have higher numbers of microfilariae, diminished cellular responsiveness to filaria-specific antigens, and an impaired Th1-type and Th2-type cytokine production [12, 13]. However, other investigators seeking to determine the influence of maternal filarial or S. mansoni infections [39, 40] on neonate immunity have found little evidence of in utero sensitization or skewed immune responses.

In onchocerciasis, a dominant expression of Th1-type immunity was found in ‘putatively immune’ [17, 18, 41] and ‘endemic control’ individuals [19], while Th2-type cytokine responses were associated with chronic infection and clinical manifestation of disease. Thus, activation of prenatal and early life immune responses towards a Th2 phenotype may predispose to parasite persistence, and evidence from epidemiological [42] and experimental studies [43] suggests that in utero exposure to filarial antigens may at the same time protect from pathology. Our observations disclosed that UCBC from newborns of O. volvulus-infected and non-infected mothers secreted substantial amounts of several Th1- and Th2-type cytokines upon mitogen, O. volvulus-specific or bacteria-derived antigenic stimulation. Systemically biased cellular responsiveness towards a Th1 or Th2 pattern, however, was not observed, i.e. both IFN-γ and IL-10 were produced by neonates' mononuclear cells upon stimulation with filarial antigens. Despite the fact that cellular production of IL-4 was not detectable in our study, UCBC from neonates secreted IL-13, which induces immunoglobulin isotype switching and IgG4 and IgE synthesis in immature human fetal B cells [44]. Onchocerca volvulus-specific antigens likewise stimulated production of IL-5, which is known to propagate eosinophil granulocytes. These observations, together with the OvAg-specific IgE in newborns, provide further evidence that indeed allergic sensitization by helminth antigens did occur in offspring of O. volvulus-infected mothers. Onchocerca volvulus-specific cytokine production was, however, differentially expressed, i.e. cells from children born to microfilariae-positive mothers secreted significantly more IFN-γ and less IL-10 than cells from babies born to non-patent mothers. Since Th1-type and Th2-type cytokines are mutually inhibitory, elevated IFN-γ responses may down-regulate the Th2-type cytokines and promote cell-mediated inflammatory reaction and DTH. Despite the fact that we were unable to detect cellular production of IL-2 and IL-4 in response to OvAg in offspring from O. volvulus-infected mothers, expression of immunity in neonates appeared Th0-like, resembling immune responsiveness as observed in adults exposed to infection [15, 19]. Low level production of IL-2 by UCBC in response to helminth-specific antigens [39] has been reported previously. IL-2 is an autocrine growth factor and difficult to measure in antigen-stimulated cell cultures, and therefore the lack of IL-2 may simply reflect the use of the cytokine as it is produced.

To date, investigations into the consequences of prenatal sensitization by helminth parasites have presented contrasting evidence. Our study has added further evidence that maternal infections will indeed sensitize, in utero, for parasite-specific cellular responsiveness in neonates, and also activate O. volvulus antigen-specific production of several Th1- and Th2-type cytokines, but it remains unknown how long such specific reactivity may persist and the extent to which prenatal sensitization may alter resistance or susceptibility to filarial infection. As an equally important factor, the epidemiological situation in onchocerciasis-endemic areas, i.e. repeated exposure to infection, transmission intensity, individual genetic predisposition, and concurrent helminth infections, may decisively influence post-natal development of immunocompetence. Only long-term follow up of children in a well defined epidemiological situation may resolve this as yet enigmatic issue; and our ongoing investigations are addressing the extent to which prenatal exposure to O. volvulus may contribute to differential clinical and immunological outcomes of infection in later life.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Togolese Ministry of Health. We gratefully acknowledge the invaluable support of midwives and medical assistants at village dispensaries and the expert technical assistance of the laboratory staff at the Centre Hospitalier de la Région Centrale in Sokodé/Togo. This work was supported by the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation (Grant 5996), by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Grant So367/1), the fortuene-Programme (Grant 1490095) of University Tübingen, and the Dr Peter Stingl Afrika Fonds.

REFERENCES

- 1.King CL, Nutman TB. Regulation of the immune response in lymphatic filariasis and onchocerciasis. Immunol Today. 1992;12:A54–8. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5699(05)80016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beaver PC. Filariasis without microfilaremia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1970;19:181–9. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1970.19.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewert RM, Mandlowitz S. Schistosomiasis: prenatal induction of tolerance to antigen. Nature. 1969;224:1029–30. doi: 10.1038/2241029a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haque A, Capron A. Transplacental transfer of rodent microfilariae induces antigen-specific tolerance in rats. Nature. 1982;299:361–3. doi: 10.1038/299361a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hightower AW, Lammie PJ, Eberhard ML. Maternal infection—a persistent risk factor for microfilaremia in offspring? Parasitol Today. 1993;9:418–21. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(93)90051-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlier Y, Truyens C. Influence of maternal infection on offspring resistance towards parasites. Parasitol Today. 1995;11:94–99. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(95)80165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loke YW. Transmission of parasites across the placenta. Adv Parasitol. 1982;21:155–228. doi: 10.1016/s0065-308x(08)60276-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zanetti V, Lambrecht FL. Notes sur la malaria indigène au Nepoko. Ann Soc Belg Med Trop. 1948;28:355–70. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brinkmann UK, Krämer P, Presthus GT, Sawadogo B. Transmission in utero of microfilariae of Onchocerca volvulus. Bull WHO. 1976;54:708–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schulz-Key H, Windmöller DA, Weiss N, Helling-Giese G, Görgen H, Soboslay PT. The role of transplacental transmission of Onchocerca volvulus microfilariae in an area endemic for onchocerciasis in Togo. Zbl Bkt Hyg. 1992;325:82–83. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eberhard ML, Hitch WL, McNeeley DF, Lammie PJ. Transplacental transmission of Wuchereria bancrofti in Haitian women. J Parasitol. 1993;79:62–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steel C, Guinea A, McCarthy J, Ottesen EA. Long-term effect of prenatal exposure to maternal microfilaraemia on immune responsiveness to filarial parasite antigens. Lancet. 1994;343:890–3. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elson LH, Days A, Calvopina M, Wilson Paredes Y, Araujo E, Guderian RH, Bradley JE, Nutman TB. In utero exposure to Onchocerca volvulus: relationship to subsequent infection intensity and cellular immune responsiveness. Inf Immun. 1996;64:5061–5. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5061-5065.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soboslay PT, Lüder CGK, Hoffmann WH, et al. Ivermectin-facilitated immunity in onchocerciasis. Activation of parasite-specific Th1 type responses with subclinical Onchocerca volvulus infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994;96:238–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06548.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soboslay PT, Geiger SM, Weiss N, et al. The diverse expression of immunity in humans at distinct states of Onchocerca volvulus infection. Immunol. 1997;90:592–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00210.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maizels RM, Bundy DAP, Selkirk ME, Smith AF, Anderson RM. Immunological modulation and evasion by helminth parasites in human populations. Nature. 1993;365:797–805. doi: 10.1038/365797a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ward DJ, Nutman TB, Zea-Flores G, Portocarrero C, Lujan A, Ottesen EA. Onchocerciasis and immunity in humans: enhanced T cell responsiveness to parasite antigen in putatively immune individuals. J Inf Dis. 1988;157:536–43. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.3.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elson LH, Calvopina MH, Paredes WY, Araujo E, Bradley JE, Guderian RH, Nutman TB. Immunity in onchocerciasis: putative immune persons produce a Th1-like response to Onchocerca volvulus. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:652–9. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.3.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lüder CGK, Schulz-Key H, Banla M, Pritze S, Soboslay PT. Immunoregulation in onchocerciasis: predominance of Th1-type responsiveness to low molecular weight antigens of Onchocerca volvulus in exposed individuals without microfilaridermia and clinical disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;105:245–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-747.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ridge JP, Fuchs EJ, Matzinger P. Neonatal tolerance revisited: turning on newborn T cells with dendritic cells. Science. 1996;271:1723–6. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5256.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barrios C, Brawand P, Berney M, Brandt C, Lambert PH, Siegrist CA. Neonatal and early life immune responses to various forms of vaccine antigens qualitatively differ from adult responses: predominance of a Th2-biased pattern which persists after adult boosting. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1489–96. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boehmer von H, Teh HS, Kisielow P. The thymus selects the useful, neglects the useless and destroys the harmful. Rarasitol Today. 1989;10:57–61. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(89)90307-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weil GJ, Hussain R, Kumaraswami V, Tripathy SP, Phillips KS, Ottesen EA. Prenatal sensitization to helminth antigens in offspring of parasite-infected mothers. J Clin Invest. 1983;71:1124–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI110862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Remme JHF, De Sole G, Oortmarsen van GJ. The predicted and observed decline in onchocerciasis infection during 14 years of successful control of Simulium spp. In West Africa. Bull WHO. 1990;69:331–9. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Sole G, Accorsi S, Cresveaux J, Remme J, Walsh F, Hendrickx J. Distribution and severity of onchocerciasis in southern Benin, Ghana and Togo. Acta Tropica. 1992;52:87–97. doi: 10.1016/0001-706x(92)90024-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lal PB, Ottesen EA. Enhanced diagnostic specificity in human filariasis by IgG4 antibody assessment. J Inf Dis. 1988;161:549–54. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.5.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greene GM, Fanning MM, Ellner JJ. Non-specific suppression of antigen-induced lymphocyte blastogenesis in Onchocerca volvulus infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 1983;96:259–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soboslay PT, Weiss N, Dreweck CM, Taylor HR, Brotman B, Schulz-Key H, Greene BM. Experimental onchocerciasis in chimpanzees: antibody response and antigen recognition after primary infection with Onchocerca volvulus. Exp Parasitol. 1992;74:367–80. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(92)90199-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Forsthuber T, Yip HC, Lehman PV. Induction of TH1 and TH2 immunity in neonatal mice. Science. 1996;271:1728–30. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5256.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Desowitz RS, Elm J, Alpers MP. Plasmodium falciparum-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG), IgM, and IgE antibodies in paired maternal-cord sera from east Sepik province, Papua New Guinea. Inf Immun. 1993;61:988–93. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.3.988-993.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petralanda I, Yarzabal L, Piessens WF. Parasite antigens are present in breast milk of women infected with Onchocerca volvulus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988;38:372–9. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1988.38.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prescott SL, Macaubas C, Holt BJ, Smallacombe TB, Loh R, Sly PD, Holt PG. Transplacental priming of the human immune system to environmental allergens: universal skewing of the initial T cell responses toward the Th2 cytokine profile. J Immunol. 1998;160:4730–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Constant S, Pfeiffer C, Woodard A, Pasqualini T, Bottomly K. Extent of T cell receptor ligation can determine the functional differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1591–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hosken NA, Shibuya K, Heath AW, Murphy KM, O'Garra A. The effect of antigen dose on CD4+ T helper cell phenotype development in a T cell receptor-αβ-transgenic model. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1579–84. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roser BJ. Cellular mechanisms in neonatal and adult tolerance. Immunol Rev. 1989;107:179–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1989.tb00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson CB, Lewis DB. Basis and implications of selectively diminished cytokine production in neonatal susceptibility to infection Rev. Infect Dis. 1990;12:S410–20. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.supplement_4.s410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goodnow CC. Balancing immunity and tolerance: deleting and tuning lymphocyte repertoires. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2264–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sarzotti M, Robbins SS, Hoffman PM. Induction of protective CTL responses in newborn mice by a murine retrovirus. Science. 1996;271:1726–8. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5256.1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malhotra I, Ouma J, Wamachi A, et al. In utero exposure to helminth and mycobacterial antigens generates cytokine responses similar to that observed in adults. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:1759–66. doi: 10.1172/JCI119340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hitch WL, Eberhard ML, Lammie PJ. Investigation of the influence of maternal infection with Wuchereria bancrofti on the humoral and cellular responses of neonates to filarial antigens. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1997;91:461–9. doi: 10.1080/00034989760824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dimock KA, Eberhard ML, Lammie PJ. Th1-like antifilarial immune responses predominate in antigen-negative persons. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2962–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.2962-2967.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lammie PJ, Hitch WL, Walker-Allen EM, Hightower W, Eberhard ML. Maternal filarial infection as risk factor for infection in children. Lancet. 1991;27:1005–6. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92661-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klei TR, Blanchard DP, Coleman SU. Development of Brugia pahangi infections and lymphatic lesions in male offspring of female jirds with homologous infections. Trans Roy Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1986;80:214–6. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(86)90014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Punnonen J, deVries JE. IL-13 induces proliferation, Ig isotype switching, and Ig synthesis in immature human fetal B cells. J Immunol. 1994;152:1094–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]