Abstract

The CD14 molecule, which is known to be a receptor for endotoxin, is expressed on monocytes and neutrophils. It is found as a soluble CD14 (sCD14) in circulation, and the plasma level has been shown to be increased in some infectious diseases, including sepsis. To investigate the potential significance of circulating sCD14 in Kawasaki disease (KD), the plasma level of sCD14 was measured using ELISA in patients with KD, patients with a Gram-negative bacterial infection (GNBI) including sepsis, patients with viral infection (VI), and healthy controls. We also analysed CD14 receptor expression in monocytes and neutrophils using flow cytometry and a semiquantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction. Although KD patients had significantly lower counts of peripheral neutrophils and monocytes than GNBI patients, KD patients had significantly higher levels of sCD14 than GNBI. No significant correlations were observed between sCD14 levels and clinical laboratory values or the cytokine (interferon-gamma, tumour necrosis factor-alpha) levels in the acute phase. The mean intensity of CD14 receptor expression on neutrophils markedly increased in the acute phases of KD and GNBI compared with that in their convalescent phases, while that on monocytes decreased. The expression of CD14 mRNA in neutrophils increased in the acute phases of KD and GNBI, while that in monocytes did not decrease but instead remained quite abundant. The present findings suggest that the elevated level of circulating sCD14 appears to be an important parameter for KD and that sCD14 shedding is accompanied by different kinetics regarding the expression of CD14 antigen and CD14 gene between monocytes and neutrophils.

Keywords: Kawasaki disease, CD14, monocytes, neutrophils

INTRODUCTION

CD14 is originally a myeloid differentiation antigen detected on mature monocytes and macrophages [1] and is also expressed on neutrophils to a lesser extent [2]. CD14 has been shown to be a key molecule responsible for the innate recognition of bacteria by human cells and also functions as a receptor for lipopolysaccharide (LPS, endotoxin) derived from the outer surface of Gram-negative bacteria [3,4]. A soluble form of CD14 (sCD14) is found in normal sera [5] and the sCD14 level also increases in septic patients [6]. Furthermore, the sCD14 level is higher in infants with Gram-negative sepsis than in those with Gram-positive sepsis [7]. The source of sCD14 in such patients is unclear, but it is thought to be a by-product of CD14-expressing cells (monocytes and neutrophils) [8]. In addition, CD14 expression on their surfaces and sCD14 shedding are regulated by LPS, several cytokines and other stimuli [8]. sCD14 is thought to either protect or enhance the response to LPS [3,9], but the pathophysiological role of sCD14 is still not completely understood.

Kawasaki disease (KD) is an acute febrile illness which predominantly affects infants and children [10]. It is characterized by systemic vasculitis including coronary artery involvement [11]. The aetiology of this disease is still unknown; however, we recently demonstrated that bacterial LPS is bound to circulating neutrophils via CD14 on their surfaces in KD and that the LPS-bound neutrophils secrete an excess amount of elastase into the circulation, thus suggesting that endotoxin may be involved in the pathogenesis of KD [12]. CD14+ monocytes/macrophages have also been reported to increase during the acute phase of KD [13,14]. We therefore became interested in the kinetics of circulating sCD14 in KD. The aim of the present study was thus to investigate the significance of sCD14 in the pathogenesis of KD. Furthermore, we also analysed the regulation of CD14 receptor expression in circulating monocytes and neutrophils at the protein level on their surfaces and at the mRNA level.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients and sample preparations

We evaluated 30 patients with KD (aged 3 months to 9 years, median 20 months), 10 patients with a Gram-negative bacterial infection (GNBI; aged 3 months to 5 years, median 19 months), 10 patients with a viral infection (VI; aged 6 months to 8 years, median 24 months), 17 healthy children (aged 6–24 months, median 17 months), and 10 healthy adults (aged 24–43 years, median 30 years). Informed consent was obtained from the parents of all children. In addition, all patients were hospitalized at the National Defense Medical College Hospital between February 1996 and February 1998. All KD patients were enrolled within 8 days of the onset of illness, with day 1 defined as the first day of fever, and all also met the diagnostic criteria for KD established by the Japanese Kawasaki Disease Research Committee [15]. No bacterial species were identified in the blood culture from the KD patients. The GNBI group included six children with sepsis (four with Haemophilus influenzae, one with Salmonella, and one with Escherichia coli) and four children with a urinary tract infection due to E. coli. These organisms were isolated from both blood and urine cultures. The VI group included febrile patients consisting of three with an upper respiratory infection, four with bronchitis, and one each with enterocolitis, aseptic meningitis or croup. Although a viral culture was not carried out, the C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were < 0.6 mg/dl in all patients in this group. Blood samples were obtained from patients in the acute phase during the febrile period and in the convalescent phase when the CRP level was < 0.3 mg/dl. The plasma samples were stored at −80°C until analysed. The peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) and neutrophils were immediately separated by density gradient centrifugation using a Mono-Poly Resolving Medium (ICN Biochemicals, Costa Mesa, CA) and were then washed with PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Next, the monocytes were isolated from the mononuclear cells. Briefly, the mononuclear cells were resuspended in RPMI 1640 (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO) containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 2 mm glutamine, penicillin, and streptomycin, and were cultured for 1 h at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere in plastic Petri dishes. After removing non-adherent cells, the dishes were washed and adherent monocytes were collected. The studies were approved by the National Defense Medical College Institutional Review Board.

Assay for sCD14, interferon-gamma and tumour necrosis factor-alpha

The plasma levels of sCD14, interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) were measured using an ELISA kit (sCD14, IBL, Hamburg, Germany; IFN-γ and TNF-α, Central Laboratory of the Netherlands Red Cross Blood Transfusion Service, Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

Flow cytometric analysis

The mononuclear cells and neutrophils (5 × 105/ml) were immediately exposed to FITC-conjugated anti-CD14 MoAb (Tük4; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) or non-specific mouse IgG2a-FITC (isotype-negative control MoAb). All samples were analysed with a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). After setting the gates separately around the monocyte and neutrophil populations, the data were acquired using CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson).

Semiquantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction of CD14 mRNA

The total RNA was extracted separately from isolated monocytes and neutrophils (104 cells) with the acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform method (Isogen kit; Nippon Gene, Toyama, Japan). First-strand cDNA was generated from the RNA samples using Ready-to-Go You-Prime First-Strand Beads (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden). Two pairs of oligonucleotides primers were prepared for human CD14-specific sequences (sense, 5′ TAAAGGACTGCCAGCCAAGC 3′; anti-sense, 5′ AGCCAAGG CAGTTTGAGTCC) [16] and β-actin-specific sequences (sense, 5′ AACTGGGACGACATGGAGAA 3′; anti-sense, 5′ ATACCCCT CGTAGATGGGCA 3′) [17]. Semiquantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was carried out with 1 μl of cDNA, 1 U of Taq polymerase, 0.4 mm dNTP, and 20 pmol of each 3′ and 5′ primer in the PCR buffer (total volume of 50 μl). Each sample was then subjected to 30 cycles of amplification consisting of 1 min denaturation at 94°C, 2 min primer annealing at 60°C, and 3 min extension at 72°C. The PCR products were separated by 4% PAGE and the gels were viewed by UV transillumination.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± s.d. Any differences between the acute and convalescent phases in the same group were assessed by the Wilcoxon signed rank test. Intergroup differences were analysed with the Mann–Whitney test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Patient profiles and laboratory findings

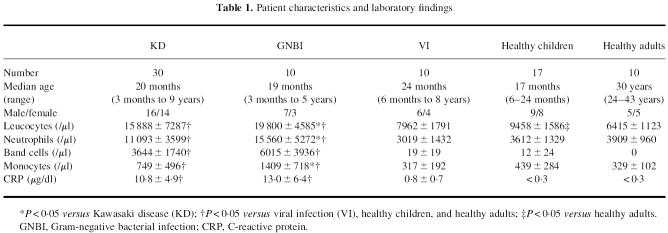

The patients and healthy controls enrolled in this study were classified into five groups: KD, GNBI, VI, healthy children, and healthy adults (Table 1). The mean counts of leucocytes, neutrophils, band cells and monocytes, and mean CRP levels were significantly higher in patients with KD and GNBI than in VI, the healthy children, and healthy adults. Furthermore, the GNBI patients had significantly higher levels of leucocytes as well as higher neutrophil and monocyte counts than did KD patients.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and laboratory findings

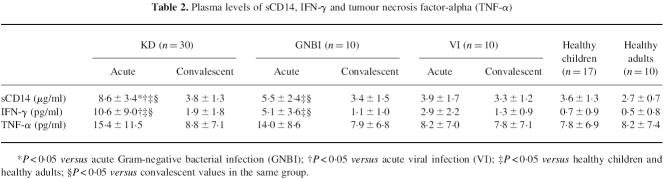

Plasma levels of sCD14, IFN-γ and TNF-α

Patients with KD and GNBI had significantly higher levels of sCD14 in their acute phases than in their convalescent phases and in both healthy children and healthy adults (Table 2). Furthermore, the mean sCD14 level was significantly higher in the acute phase of KD than in the acute phases of GNBI and VI. No significant difference was observed in the sCD14 level between the six patients with sepsis and the four patients without sepsis in the GNBI group, and the KD patients also had a significantly higher level of sCD14 than the six patients with Gram-negative sepsis. The mean IFN-γ level significantly increased in the acute phases of KD and GNBI compared with the mean levels in their convalescent phases, in the acute phase of VI, and in both healthy children and healthy adults. The IFN-γ level tended to be higher, but not significantly so, in the acute phase of KD than in the acute phase of GNBI. The mean TNF-α level was slightly higher, but not significantly so, in the acute phases of KD and GNBI than the mean levels in their convalescent phases, in the acute phase of VI, and in both healthy children and adults.

Table 2.

Plasma levels of sCD14, IFN-γ and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α)

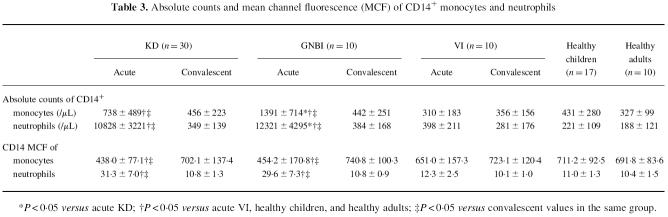

CD14 expression on the surfaces of monocytes and neutrophils

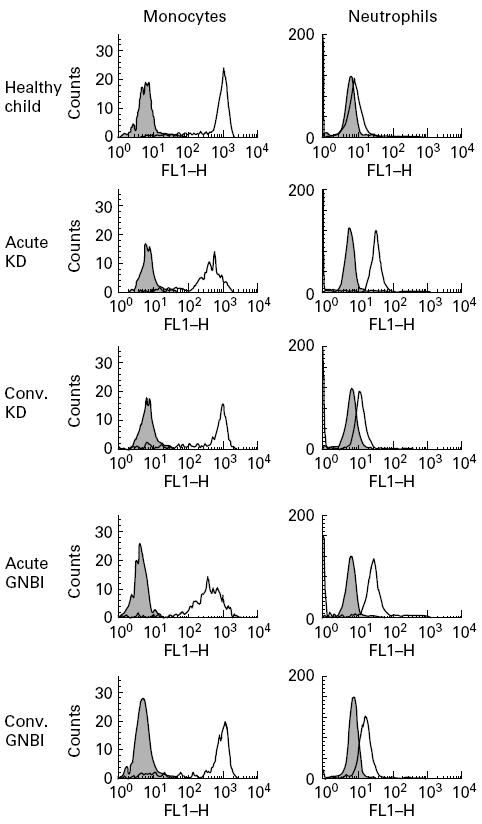

Figure 1 demonstrates the histograms of flow cytometric analysis for representative cases. CD14 expression on monocytes was abundant in a healthy child, while that on neutrophils was very weak. The fluorescent intensity of CD14 expression on monocytes decreased in the acute phases of both KD and GNBI, whereas that on neutrophils increased. In the convalescent phases of KD and GNBI, the fluorescent levels of CD14 expression on monocytes and neutrophils recovered to the level seen in a healthy child.

Fig. 1.

CD14 expressions on the surfaces of monocytes and neutrophils. Cells, stained with isotype-matched mouse IgG2a–FITC (shaded histograms) and anti-CD14 MoAb–FITC (thick lines), were analysed using a flow cytometer in a healthy child and the acute and convalescent (conv.) phases of a Kawasaki disease (KD) patient and a Gram-negative bacterial infection (GNBI) patient.

The absolute count of CD14+ monocytes and neutrophils and the CD14 mean channel fluorescence (MCF), an indicator of receptor density, on monocytes and neutrophils were averaged in each group (Table 3). The absolute counts of CD14+ monocytes and neutrophils were significantly higher in the acute phases of KD and GNBI than in their convalescent phases, VI, healthy children, and healthy adults. Furthermore, the mean counts of CD14+ monocytes and neutrophils were significantly higher in the acute phase of GNBI than in the acute phase of KD. The CD14 MCF on monocytes was significantly lower in the acute phases of KD and GNBI than in their convalescent phases. In contrast, the mean CD14 MCF on neutrophils was significantly higher in the acute phases of KD and GNBI than in their convalescent phases. There were no significant differences in the CD14 MCF for either monocytes or neutrophils between KD and GNBI in the acute phase.

Table 3.

Absolute counts and mean channel fluorescence (MCF) of CD14+ monocytes and neutrophils

In the acute phases of KD and GNBI, no significant correlation was seen between the laboratory values (leucocyte, neutrophil, band cell, monocyte counts, and CRP level), sCD14 levels, cytokine (IFN-γ and TNF-α) levels, absolute counts of CD14+ monocytes and neutrophils, and the CD14 MCF on monocytes and neutrophils.

CD14 mRNA expression in monocytes and neutrophils

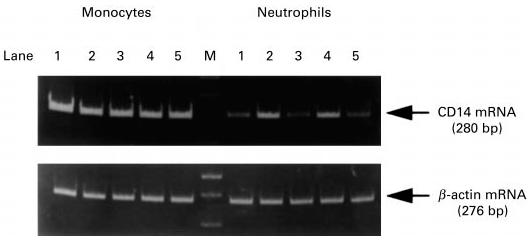

Figure 2 shows the profiles of reverse transcription (RT)-PCR for representative cases. The monocytes expressed CD14 mRNA constitutively at high levels in a healthy child. In the acute and convalescent phases of KD and GNBI, patients had an abundant expression of CD14 mRNA in the monocytes at nearly the same level as in the healthy child. In contrast, CD14 mRNA in the neutrophils was expressed at a low level in the healthy child. The extent of CD14 mRNA expression in the neutrophils increased in the acute phases of KD and GNBI, recovering to low levels in the convalescent phases of KD and GNBI. Similar expression patterns of CD14 mRNA were seen in other patients with KD and GNBI (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

CD14 mRNA expression in monocytes and neutrophils. Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction products using primers specific for CD14 and β-actin are displayed for a healthy child, a Kawasaki disease (KD) patient and a Gram-negative bacterial infection (GNBI) patient. Lane 1, healthy child; lane 2, acute KD; lane 3, convalescent KD; lane 4, acute GNBI; lane 5, convalescent GNBI. M indicates a molecular weight marker (100-bp ladder).

DISCUSSION

In the present study we demonstrate that KD patients had a significantly higher level of sCD14, although the level of circulating monocytes and neutrophils was lower than in GNBI patients. CD14 expression on the surface of monocytes decreased with constitutively abundant amounts of CD14 mRNA in the acute phases of both KD and GNBI, while CD14 expression on the surface of neutrophils increased with higher levels of CD14 mRNA expression in the acute phases of KD and GNBI than in their convalescent phases.

CD14, a 55-kD glucosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored membrane protein, lacks transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains and is expressed on both monocytes and activated neutrophils [1,2]. sCD14 is thought to be released from the cell surfaces either due to the action of phospholipases or by protease digestion [3,8]. The shedding of leucocyte CD14 is constitutive and inducible. sCD14 is detected in the culture supernatants of untreated monocytes and neutrophils [2,18]. sCD14 can also be shed from the surfaces of monocytes in response to LPS, cytokines (IFN-γ and TNF-α) and other stimuli in vitro [8,18]. Clinical observations have demonstrated the circulating sCD14 levels to increase in sepsis, especially Gram-negative sepsis [6,7], and this increased level is associated with a high mortality in Gram-negative septic shock [6] and with signs of septicaemia in patients with polytrauma and severe burns [19]. Serum sCD14 is also reported to increase in other diseases such as AIDS [20], atopic dermatitis [21] and liver disease [22], but there have so far been no reports in which the sCD14 levels were compared between these diseases and Gram-negative sepsis. The present study showed circulating sCD14 to be significantly elevated in the acute phase of KD compared with GNBI, including sepsis. These findings thus suggest that the increased sCD14 levels reflect the intense cytokine-mediated inflammation of KD, although the elevation of sCD14 is not specific for acute KD. Further investigations of serum sCD14 levels therefore need to be done in patients who have other infectious diseases in addition to the increased cytokine levels in the serum.

Functionally, sCD14 has two opposite effects in vitro. sCD14 can inhibit the binding of the LPS–LPS binding protein complex to the CD14 receptor and can also inhibit LPS-induced cytokine secretion by mononuclear cells [23,24]. sCD14 has also been reported to participate in LPS elimination in vivo in patients with Gram-negative sepsis [25]. In contrast, sCD14 forms complexes with LPS and can enhance the LPS-induced response (activation and damage) of CD14− cells such as endothelial cells [3,26]. sCD14 also mediates the permeability-increasing effect of LPS on endothelial cells in a dose-dependent manner [27,28]. KD vasculitis is pathologically characterized by endothelial activation, degeneration, and increased vascular permeability [29,30]. The pathophysiological role of sCD14 in KD remains obscure in the present study. However, the abnormally increased level of sCD14 in KD may support our theory of endotoxin involvement in its pathogenesis, and it is thus possible that the sCD14 is involved in the elimination of LPS and/or the endothelial cell injury due to LPS in KD. Leung et al. have also proposed that KD may be caused by a bacterial superantigen [31]. Although there is no evidence to prove that the serum sCD14 levels rise in superantigen-mediated diseases, superantigen may also release sCD14 into the circulation due to its intense inflammatory response.

CD14 expression on monocytes stimulated with LPS in vitro has been reported to be down-regulated [18], and CD14 expression on monocytes is down-regulated in patients with sepsis, especially Gram-negative sepsis [32,33]. There have been no reports in which the regulation of CD14 expression was analysed in both monocytes and neutrophils from septic patients. In the present flow cytometric analysis, the intensity of CD14 expression on monocytes, which naturally have an abundant CD14 expression, decreased, while that on neutrophils, which naturally have a low CD14 expression, increased in the acute phases of KD and GNBI. Since the expression of CD14 mRNA in monocytes did not decrease in the acute phase, the decreased CD14 expression on monocytes may not be caused by the inhibition of CD14 protein synthesis in them but instead by shedding from their surfaces. These findings suggest monocytes to be a major source of sCD14 in KD and GNBI. However, sCD14 may also be shed from neutrophils, because the sCD14 levels increase concomitantly with the cell surface expression of CD14 in vitro [8]. Since the kinetics of CD14 receptor expression in both monocytes and neutrophils was common to KD and GNBI in the present study, we could not clarify whether a greater amount of sCD14 sheds from these cells into the circulation in KD than in GNBI. IFN-γ and TNF-α are representative cytokines which can modulate the CD14 expression on monocytes and neutrophils and the sCD14 shedding in vitro [8,34], but in the present study no significant correlation was observed with the IFN-γ or TNF-α levels and sCD14 values or CD14 MCF on circulating monocytes and neutrophils in the acute phases of KD and GNBI. The relevant monocytes and neutrophils in the tissues may contribute to the elevated levels of sCD14. It is also possible that sCD14 is released from other cells than monocytes and neutrophils in KD patients, because CD14 mRNA has been reported to be detected in a variety of murine organs and non-myeloid cells treated with LPS [35].

In conclusion, a significant up-regulation of sCD14 shedding beyond GNBI is seen in KD, thus suggesting that the increased level of sCD14 in the circulation may be one of the inflammatory markers for KD vasculitis. sCD14 shedding is accompanied by the different kinetics in CD14 cell surface expression and the CD14 gene between the circulating monocytes and neutrophils, although this phenomenon is also commonly seen in both KD and GNBI. The exact mechanism of sCD14 shedding in KD may therefore be important for elucidating KD pathogenesis and should thus be further investigated in the future.

REFERENCES

- 1.Haziot A, Chen S, Ferrero E, Low MG, Silber R, Goyert SM. The monocyte differentiation antigen, CD14, is anchored to the cell membrane by a phosphatidylinositol linkage. J Immunol. 1988;141:547–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haziot A, Tsuberi B-Z, Goyert SM. Neutrophil CD14: biochemical properties and role in the secretion of tumor necrosis factor-α in response to lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 1993;150:5556–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ulevitch RJ, Tobias PS. Receptor-dependent mechanisms of cell stimulation by bacteria endotoxin. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:437–57. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.002253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright SD. CD14 and innate recognition of bacteria. J Immunol. 1995;155:6–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bazil V, Horejsi V, Baudys M, et al. Biochemical characterization of a soluble form of the 53-kDa monocyte surface antigen. Eur J Immunol. 1986;16:1583–9. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830161218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Landmann R, Zimmerli W, Sansano S, et al. Increased circulating soluble CD14 is associated with high mortality in gram-negative septic shock. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:639–44. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.3.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blanco A, Solis G, Arranz E, Coto GD, Ramos A, Telleria J. Serum levels of CD14 in neonatal sepsis by gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Acta Paediatr. 1996;85:728–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1996.tb14135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ziegler-Heitbrock HWL, Ulevitch RJ. CD14: cell surface receptor and differentiation marker. Immunol Today. 1993;14:121–5. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90212-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maliszewski CR. CD14 and immune response to lipopolysaccharide. Science. 1991;252:1321–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1718034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawasaki T, Kosaki F, Okawa S, Shigematsu I, Yanagawa H. A new infantile acute febrile mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome (MLNS) prevailing in Japan. Pediatrics. 1974;54:271–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kato H, Koike S, Yamamoto M, Ito Y, Yano E. Coronary aneurysms in infants and young children with acute febrile mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome. J Pediatr. 1975;86:892–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(75)80220-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takeshita S, Nakatani K, Kawase H, et al. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide-bound neutrophils in Kawasaki disease. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:508–12. doi: 10.1086/314600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furukawa S, Matsubara T, Motohashi T, Nakachi S, Sasai K, Yabuta K. Expression of FcεR2/CD23 on peripheral blood macrophages/monocytes in Kawasaki disease. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1990;56:280–6. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(90)90149-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furukawa S, Matsubara T, Yabuta K. Mononuclear cell subsets and coronary artery lesions in Kawasaki disease. Arch Dis Child. 1992;67:706–8. doi: 10.1136/adc.67.6.706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Japan Kawasaki Disease Research Committee. Tokyo: Japan Kawasaki Disease Research Committee; 1984. Diagnostic guidelines of Kawasaki disease, 4th revised edn. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cosentino G, Soprana E, Thienes CP, Siccardi AG, Viale G, Vercelli D. IL-13 down-regulates CD14 expression and TNF-α secretion in normal human monocytes. J Immunol. 1995;155:3145–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takeshita S, Kawase H, Yamamoto M, Fujisawa T, Sekine I, Yoshioka S. Increased expression of human 63-kD heat shock protein gene in Kawasaki disease determined by quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction. Pediatr Res. 1994;35:179–83. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199402000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bazil V, Strominger JL. Shedding as a mechanism of down-regulation of CD14 on stimulated human monocytes. J Immunol. 1991;147:1567–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krüger C, Schütt C, Obertacke U, et al. Serum CD14 levels in polytraumatized and severely burned patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 1991;85:297–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1991.tb05722.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krüger C, Schütt C, Dietz H, et al. Elevated levels of soluble CD14 molecules in serum of HIV-1 infected patients. Immunobiology. 1990;181:244(A). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wüthrich BK, Kägi MK, Joller-Jemelka H. Soluble CD14 but not interleukin-6 is a new marker for clinical activity in atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol Res. 1992;284:339–42. doi: 10.1007/BF00372036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oesterreicher C, Pfeffel F, Petermann DM, Müller C. Increased in vitro production and serum levels of the soluble lipopolysaccharide receptor sCD14 in liver disease. J Hepatol. 1995;23:396–402. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80197-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haziot A, Rong G-W, Bazil V, Silver J, Goyert SM. Recombinant soluble CD14 inhibits LPS-induced tumor necrosis factor-α production by cells in whole blood. J Immunol. 1994;152:5868–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schütt C, Schilling T, Grunwald U, Schönfeld W, Krüger C. Endotoxin-neutralizing capacity of soluble CD14. Res Immunol. 1992;143:71–78. doi: 10.1016/0923-2494(92)80082-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hiki N, Berger D, Prigl C, et al. Endotoxin binding and elimination by monocytes: secretion of soluble CD14 represents an inducible mechanism counteracting reduced expression of membrane CD14 in patients with sepsis and in a patient with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1135–41. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.1135-1141.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pugin J, Schürer-Maly C-C, Leturcq D, Moriarty A, Ulevitch RJ, Tobias PS. Lipopolysaccharide activation of human endothelial and epithelial cells is mediated by lipopolysaccharide-binding protein and soluble CD14. Immunology. 1993;90:2744–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldblum SE, Brann TW, Ding X, Pugin J, Tobias PS. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-binding protein and soluble CD14 function as accessory molecule for LPS-induced changes in endothelial barrier function, in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:692–702. doi: 10.1172/JCI117022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishii Y, Shuyi W, Kitamura S. Soluble CD14 in serum mediates LPS-induced increase in permeability of bovine pulmonary arterial endothelial cell monolayers in vitro. Life Sci. 1995;56:2263–72. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)00216-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leung DYM, Cotran RS, Kurt-Jones E, Burns JC, Newburger JW, Pober JS. Endothelial cell activation and high interleukin-1 secretion in the pathogenesis of acute Kawasaki disease. Lancet. 1989;2:1298–302. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91910-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amano S, Hazama F, Hamashima Y. Pathology of Kawasaki disease I. Pathology and morphogenesis of the vascular changes. Jpn Circ J. 1979;43:633–43. doi: 10.1253/jcj.43.633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leung DYM, Meissner HC, Fulton DR, Murray DL, Kotzin BL, Schlievert PM. Toxic shock syndrome toxin-secreting Staphylococcal aureus in Kawasaki disease. Lancet. 1993;342:1385–8. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92752-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Birkenmaier C, Hong YS, Horn JK. Modulation of the endotoxin receptor (CD14) in septic patients. J Trauma. 1992;32:473–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fingerle G, Pforte A, Passlick B, Blumenstein M, Ströbel M, Ziegler-Heitbrock HWL. The novel subset of CD14+/CD16+ blood monocytes is expanded in sepsis patients. Blood. 1993;82:3170–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takeshita S, Nakatani K, Takata Y, Kawase H, Sekine I, Yoshioka S. Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) enhance lipopolysaccharide binding to neutrophils via CD14. Inflamm Res. 1998;47:101–3. doi: 10.1007/s000110050290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fearns C, Kravchenko VV, Ulevitch RJ, Loskutoff DJ. Murine CD14 gene expression in vivo: extramyeloid synthesis and regulation by lipopolysaccharide. J Exp Med. 1995;181:857–66. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.3.857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]