Abstract

CVID is a primary immune disorder in which hypogammaglobulinaemia may be associated with a number of T cell defects including lymphopenia, anergy, impaired lymphocyte proliferation and deficient cytokine secretion. In this study we show that T cells of CVID subjects, in comparison with control T cells, undergo spontaneous apoptosis in culture and markedly accelerated apoptosis after γ-irradiation. Although costimulation of the CD28 receptor following engagement of the TCR/CD3 receptor normally provides a second signal necessary for IL-2 secretion, CD28 costimulation in CVID does not significantly increase IL-2 production, nor does this combination of activators enhance the survival of irradiated CVID T cells, as it does for cultured normal T cells. Addition of IL-2 enhances CVID T cell survival, suggesting that the IL-2 signalling pathways are normal. CVID T cells have similar expression of Bcl-2 to control T cells. CD3 stimulation up-regulates T cell expression of bcl-xL mRNA for normal T cells, but anti-CD28 does not augment bcl-xL expression for CVID subjects with accelerated apoptosis. Defects of the CD28 receptor pathway, leading to cytokine deprivation and dysregulation of bcl-xL, could lead to poor T cell viability and some of the cellular defects observed in CVID.

Keywords: immunodeficiency diseases, T lymphocytes, apoptosis, CD28, Bcl-xl, co-stimulatory molecules

Introduction

CVID is a primary immunodeficiency disease characterized by hypogammaglobulinaemia and recurrent bacterial infections, especially of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts [1–4]. Inflammatory, autoimmune and/or granulomatous disease appear in some patients [4–6]. In spite of a number of investigations, the fundamental cause of this defect remains unknown. The primary phenotypic defect is a failure in B cell differentiation, leading to impaired secretion of immunoglobulins [7–10], but in the majority of patients there are significant T cell abnormalities, including cutaneous anergy, decreased lymphocyte proliferation and reduced production and/or expression of IL-2, IL-4 and IL-5 [11–17], whereas reduced or enhanced production of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) has been reported [14,18,19]. An impairment in early signalling events following triggering of the TCR has been suggested, since activation with phorbol esters bypasses the impairment and up-regulates both IL-2R and IL-2 production [17,20]. CD28, a 44-kD surface glycoprotein present on 80% of peripheral human T cells, is a well characterized costimulatory molecule, shown to affect multiple aspects of T cell activation [20,21]. CD28 costimulation lowers the concentration of anti-CD3 required to induce a proliferative response [22], markedly enhances the production of lymphokines by helper T cells [23–25], and activates the cytolytic potential of cytotoxic T cells.

Since lack of sufficient costimulation can lead to defective T cell proliferation and anergy, the CD28 costimulatory pathway in CVID T cells has drawn previous attention. The distribution of CD28 on CD4+ T cells is normal but there is a modest decrease of CD28 on CD8+ T cells [26]. While culture of CD3-activated CVID T cells with anti-CD28 enhances DNA synthesis, comparable to that of normal controls, IL-2 and IFN-γ production has been found deficient [26,27], and IL-10 production is not enhanced by this combination of activators [28]. Thon et al. [29] also showed that CVID T cells stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 resulted in deficient IL-2 and IL-4 production, with deficient up-regulation of CD40L on activated T cells, while CD69 was normally displayed, suggesting that a global activation defect was not present.

More recently, CD28 has emerged as a receptor important in controlling the expression of Bcl-xL, a Bcl-2-related mitochondrial protein that permits the survival of antigen-stimulated T cells [30,31]. Since defective CD28 costimulation leading to poor T cell viability could explain some of the T cell defects observed in CVID, we studied the survival of CVID T cells in culture, with and without activation of the CD3 receptor, testing the effects of CD28 costimulation. Our results show that CVID T cells demonstrate increased cell death in vitro, and in contrast to normal controls, CD3 and CD28 costimulation does not promote cell viability or augment expression of bcl-xL mRNA.

Materials and methods

Patients

These studies include 21 patients of age range 12–67 years with CVID diagnosed according to the diagnostic criteria of the WHO expert group for primary immunodeficiency diseases [1]. Specifically, these subjects had significantly reduced serum IgG and IgA and/or IgM levels. All patients were free of viral infections when studied. T and B cell numbers, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were determined for each subject. The range for CD4+ cells was 174–2490/mm3; the ratio of CD4/CD8 ranged from 0·33 to 4·64. Blood samples were collected before monthly intravenous immunoglobulin infusions were given. Healthy adult blood donors were studied in parallel.

Cells and cell culture

Mononuclear cells were isolated from heparinized whole blood or from the buffy coats of healthy donors, by density gradient centrifugation over Ficoll–Hypaque (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ). T cells were obtained by rosetting with neuraminidase-treated sheep erythrocytes, lysis with NH4Cl and depletion of monocytes and macrophages by adherence to plastic or in some cases by passage over nylon wool columns. Fluorescence staining of T cell populations showed 93–98% CD3 staining cells. T cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with fetal calf serum (FCS; 10%), l-glutamine (2 mm) and penicillin–streptomycin (100 U/ml, 100 μg/ml) (Gibco, Grand Island, NY). Cultures of CVID and normal T cells were split into three groups at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/ml: the first was cultured in medium alone, the second was stimulated with 10 μg/ml plate-immobilized anti-CD3 (OKT3; Ortho Biotech Inc., Raritan, NJ), and the third was stimulated with plate-immobilized anti-CD3 and with an optimal amount of 10 μg/ml (established in previous experiments) of antibody to CD28 (MoAb 9.3; Oncogene Corp., Seattle, WA). After 16 h, cells were removed from the culture dish and irradiated at 15 Gy with a γ-irradiator (Gamma Cell 1000; Nordion Int. Inc., Kanata, Ontario, Canada). Following irradiation, cells were re-plated and viability was assessed by propidium iodide (PI) exclusion at various times of culture. In some experiments, irradiated CVID T cells were cultured with human recombinant IL-2 (100 U/ml; Preclinical Repository, Biological Resources Branch, National Cancer Institute, Frederick, MD).

PI exclusion

At indicated time points, cells were washed in PBS and stained for 30 min with a FITC-conjugated anti-human CD3 MoAb (Coulter Corp., Hialeah, FL) or a non-binding matched isotype control. Cells were washed twice and re-suspended in 0·5 ml of PBS with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0·01% sodium azide and PI (1 g/ml; Sigma, St Louis, MO). Samples were analysed using flow cytometry (Epics Profile II; Coulter). Percent viability was determined by dividing the number of PI− CD3+ cells by the total number (PI+ and PI−) CD3+ cells. Forward light scatter characteristics of living cells were used to delete debris from the analyses.

Cell cycle analysis

Cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde, washed twice in PBS and re-suspended in 70% ethanol overnight at 4°C. Afterwards, cells were washed twice with PBS, permeabilized with Triton X-100 N-100 (Sigma) at a concentration of 0·1% and incubated in PBS with PI (50 g/ml; Sigma) and RNase A (0·1%; Boehringer, Indianapolis, IN) and the cell cycle was determined using flow cytometry. The percentage of cells in apoptosis was determined from the pre-G1 peak on the PI histogram [32].

Apo2.7 staining

In other studies, the appearance of a mitochondrial membrane protein, APO2.7, was used as a marker to detect apoptotic cells [33]. At indicated time points, cells were washed twice in PBS and stained for 30 min with APO2.7–PECy5-conjugated antibody (Coulter) and either FITC-labelled anti-human CD4 or anti-human CD8 antibody (Coulter). FITC-labelled and PECy5-labelled mouse IgG served as isotype-matched background controls. Following incubation, cells were washed twice, resuspended in 0·5 ml of PBS with 1% BSA and 0·01% sodium azide, and analysed using flow cytometry (Facscalibur; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

Intracellular Bcl-2 expression

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were washed and stained with PECy5-labelled anti-human CD3 for 30 min at 4°C. Cells were permeabilized (Permeafix; Ortho Diagnostic Ltd), washed with PBS with 1% BSA and 0·01% sodium azide and incubated with FITC-labelled anti-Bcl-2 (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) for 30 min at 4°C. FITC-labelled and PECy5-labelled mouse IgG were used as isotype-matched controls. The percentage of double-positive cells (CD3+ Bcl-2+) was determined and the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of these cells determined.

RNA isolation and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction analyses

RNA was isolated from non-stimulated, or CD3-, or CD3/CD28-stimulated T cells by C reagent (Gibco BRL) and chloroform extraction. Reverse transcription was performed using the M-MLV R/T enzyme (Gibco BRL). The reaction mixture was incubated at 40–42°C for 45 min, heated to 99°C for 5 min to denature the reverse transcriptase, cooled on ice for 5 min and stored at −20°C before use. The experimental cDNA samples were subjected to 29–32 cycles of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification on a programmable thermal controller (PTC-100; MJ Research, Inc., Watertown, MA). For PCR amplification, a 25-μl reaction was made containing 1 μl of cDNA mixture, 12·5 pmol of each primer, 0·2 mm of each dNTP, 2 mm MgCl2, and 1·25 U of Taq DNA polymerase. The amplification cycles consisted of denaturation (95°C for 1 min), annealing (58°C for 1 min), and extension (72°C for 1 min). The following primers were used: β-actin, 5′-TGA CGG GGT CAC CCA CAC TGT GCC CAT CTA-3′ and 5′-CTA GAA GCA TTG CGG TGG ACG ATG GAG GG-3′; bcl-xL, 5′-TGG TCG ACT TTC TCT CCT AC-3′ and 5′-AGA GAT CCA CAA AGA TGT CC-3′. PCR products were size fractionated by agarose electrophoresis, stained with ethidium bromide, visualized under UV light, and scanned with densitometer. Results were obtained from three independent experiments for each gene. β-actin served as a quantity control for RNA. As a positive control, Jurkat T cells transfected with either Neo gene, or a construct containing bcl-xL, provided by Dr Carl June (Naval Medical Research Center, Bethesda, MD), were included in each experiment.

DNA synthesis, cell proliferation and IL-2 production

T cells were cultured in medium alone, with plate-immobilized anti-CD3 (OKT3, 1 μg/ml in 0·01 Na phosphate buffer, pH 9·8) or with both plate-bound anti-CD3 and 1 μg/ml anti-CD28 added to the culture medium (MoAb 9.3; Bristol-Meyers, Seattle, WA). DNA synthesis was determined by adding 1 μCi/well of 3H-thymidine during the final 8 h of the 72-h culture period. Plates were harvested on a Mac III M 96-well harvester (Tomtec, Orange, CT) and counts were read on a 1450 Microbeta Plus (Wallac, Allerod, Denmark) microplate scintillation counter. All data points were performed in triplicate. Cell culture media harvested after 16 h of stimulation with plate-immobilized anti-CD3 (OKT3, 10 μg/ml in 0·01 Na phosphate buffer, pH 9·8) or with both plate-bound anti-CD3 and 10 μg/ml anti-CD28 were tested for IL-2 by ELISA using microtitre plates (Corning Easy Wash; Corning, NY) coated overnight with 2 μg/ml anti-IL-2 capture MoAb (PharMingen, San Diego, CA) in 0·1 m Na2HPO4 pH 9 buffer and blocked with PBS–Tween. A biotin-labelled anti-IL-2 detecting antibody (PharMingen) at 1 μg/ml in PBS−10% FCS was used. The plates were developed using avidin–horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Vector, Burlingame, CA) and 2,2 azino-bis substrate (Sigma). The lower limit of detection was 15·6 pg/ml.

Statistical analysis

The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare cell culture results of CVID subjects with normal controls and the Wilcoxon matched pairs signed-ranks test to compare the values within the same group of subjects.

Results

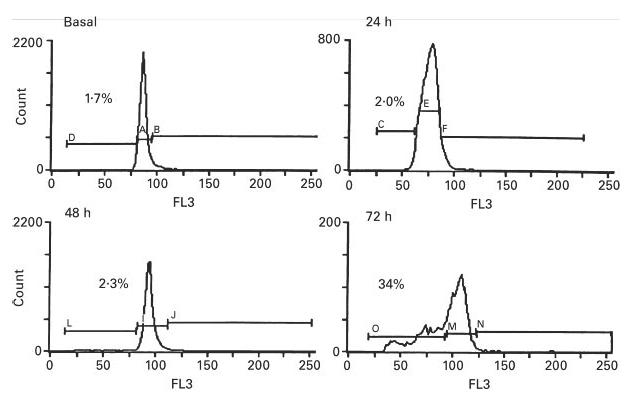

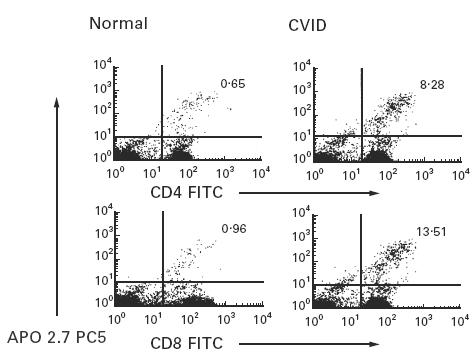

CVID T cells undergo enhanced apoptosis in vitro

Non-stimulated isolated T cells of CVID and normal subjects were cultured in complete medium to study T cell viability; PI exclusion was evaluated immediately after cell isolation and after 1, 2, 3 and 6 days of culture. In comparison with T cells of normal controls, T cells of 22 CVID subjects showed a variable but significantly reduced cell survival after 2 and 3 days of culture (Table 1). Even poorer cell viability was displayed for many CVID subjects on the day 6 of cell culture, but these results were not significantly different from the normal controls. Accelerated T cell death was most prominent for 11/22 subjects; cell cycle analysis of T cells of these subjects showed an increased percentage of subdiploid cells emerging after 72 h of cell culture (Fig. 1 shows cell cycle analysis for a CVID subject who had 34% apoptotic cells at this time point). Further confirmation of apoptosis was made by examining the appearance of a 38-kD mitochondrial membrane protein (APO2.7), an early marker of apoptosis [33]. CVID subjects had a significant increase of APO2.7+ CD4+ and CD8+ T cells as early as 24 h of culture (P < 0·05; Fig. 2). Median APO2.7+ CD4+ percentage was 5·9 (range 2·8–8·3) for five CVID versus 1·7 (range 0·6–2·6) for four normals, and median APO2.7+ CD8+ percentage was 4·6 (range 2·2–13·5) for five CVID versus 1·5 (range 0·9–2·9) for four normals.

Table 1.

Enhanced spontaneous cell death of CVID T cells†

| Day 0 | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (21) | 98·1 | 95·8 | 94·0** | 93·2* | 88·1 (NS) |

| (97·3–99·8) | (85·3–99·6) | (86·1–98·6) | (70·9–99·2) | (44·5–99·6) | |

| Controls (16) | 99·1 | 97·3 | 96·6 | 96·1 | 93·6 |

| (98·2–100) | (90·6–98·9) | (97·3–99·2) | (85·3–86·1) | (90·7–98·8) |

Data expressed as median and range (% viable cells).

CVID and normal T cells were isolated and put in culture. At the indicated time points cell viability was evaluated by CD3 staining and propidium iodide exclusion. CVID T cells had significantly poorer T cell viability after 2 and 3 days of culture

P < 0·01

P < 0·05

NS, not significant.

Fig. 1.

Cell cycle analysis of T cells of one CVID subject after permeabilization and staining with propidium iodide at 0, 24, 48, and 72 h of culture. The percentage of cells in the apoptotic fraction is indicated in each histogram. (Results similar to three other CVID subjects studied; two normal subjects showed 2·3% of apoptotic cells after 72 h of culture).

Fig. 2.

Flow cytometric detection of APO2.7–PECy5 in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells after 24 h of culture. The numbers show the percentages of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells that are positively stained for APO2.7 for one CVID subject (ratio CD4/CD8 = 3·0) in comparison with one representative control (ratio CD4/CD8 = 1·5) (five CVID and four normal controls studied).

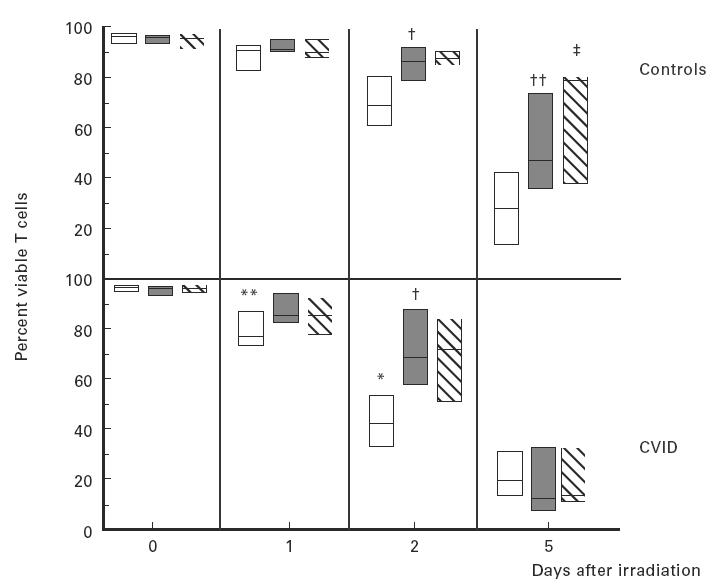

Effects of CD3 and CD3/CD28 ligation on cell survival after irradiation

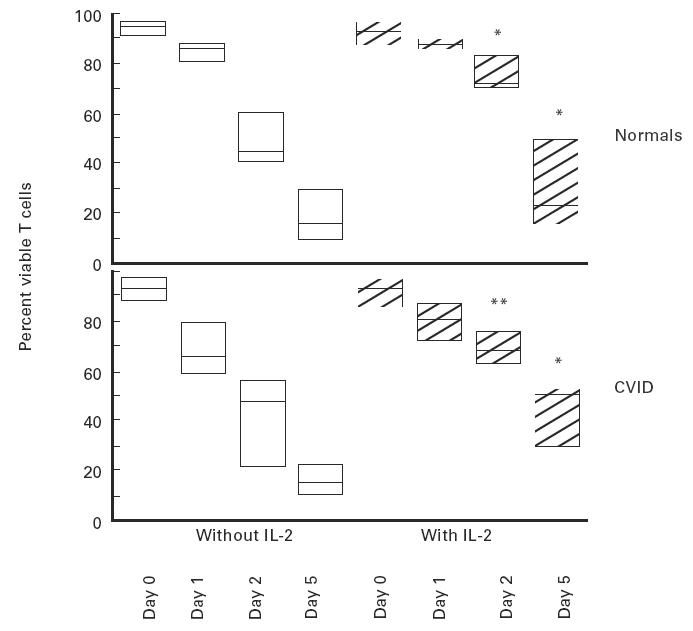

After irradiation, the viability of both normal and CVID T cells in culture declined rapidly; however, for CVID subjects the percentage of viable T cells was variable but significantly reduced compared with normal T cells (Fig. 3). To determine the degree to which anti-CD3 or anti-CD3 and CD28 costimulation enhanced the viability of irradiated T cells, cells were cultured with or without these activators. CD3 triggering enhanced the viability of irradiated T cells for both controls and for CVID subjects on the second day of cell culture (P < 0·05); the addition of anti-CD28 had little overall enhancing effect on cell viability for controls or CVID subjects at this time point. After 5 days of culture, anti-CD3 significantly enhanced cell viability for T cells of control subjects, but had no effect on the survival of CVID T cells (P < 0·05); at the same data point the addition of anti-CD28 further increased normal T cell viability in comparison with CD3 stimulation alone (P < 0·05), but had no effect on CVID T cells (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

T cells of 10 normal subjects (upper panel) or 16 CVID subjects (lower panel) were tested for survival before and following γ-irradiation. T cells were cultured in medium alone (□), or stimulated with plate-immobilized anti-CD3 alone (shaded bars) or with anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 (hatched bars) for 16 h and then exposed to 15 Gy of γ-irradiation. Percent viability of each group was assessed by CD3 staining and propidium iodide exclusion. CVID T cells had significantly poorer T cell viability on days 1 and 2 after irradiation (**P < 0·01; *P < 0·05, respectively). CD3 stimulation enhanced CVID T cell viability on day 2 (†P < 0·05) and normal T cell viability on days 2 and 5 after irradiation (††P < 0·05). CD28 costimulation further increased normal T cell viability on day 5 (‡P < 0·05). The boxes represent the range, the line inside the box represents the median value.

CD28 costimulation increases DNA synthesis but not IL-2 production

Culture of CVID T cells with MoAb CD3 resulted in significantly less DNA synthesis than for normal controls (P < 0·05), but CD28 costimulation increased thymidine incorporation of CVID T cell to levels similar to that of control T cells (Table 2). CVID T cells also produced lower levels of IL-2 than normal subjects after CD3 stimulation (P < 0·05). Moreover, CD3/CD28 costimulation increased IL-2 production for control T cells (P < 0·01), but not for CVID T cells; the difference between IL-2 production by T cells of normal controls and CVID subjects after CD3/CD28 costimulation was highly significant (P < 0·001; Table 2). There was no significant relationship between the absolute number of CD4 cells and IL-2 production in any culture condition.

Table 2.

Effects of anti-CD28 on DNA synthesis and IL-2 production§

| Controls (13) | CVID (21) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activator | 3H-thymidine incorporation (ct/min) | IL-2 production (pg/ml) | 3H-thymidine incorporation (ct/min.) | IL-2 production (pg/ml) |

| None | 74 | 6·0 | 33 | 0·5 |

| (48–114) | (0–23) | (21–99) | (0–30·4) | |

| Anti-CD3 | 2627 | 59 | 670† | 9·0*** |

| (284–14 807) | (14–291) | (72–7620) | (0–51) | |

| Anti-CD3/anti-CD28 | 20 075 | 82·8‡ | 14 596 (NS) | 8·75*** |

| (11 079–32 198) | (23–817) | (1760–37 629) | (0–114) | |

Data expressed as median and range. CVID T cells had significantly reduced CD3-induced DNA synthesis

(P < 0·05). CVID T cells had significantly reduced CD3- and CD3/CD28-induced IL-2 production

(P < 0·001). CD28 costimulation increased IL-2 production in normal T cells

(P < 0·05), but not in CVID.

IL-2 enhances cell survival

Since CD28 triggering had no significant effect on enhancing cell viability and IL-2 secretion was deficient, the effect of adding exogenous IL-2 on T cell survival was investigated. Addition of IL-2 to irradiated T cell cultures significantly reduced apoptosis for CVID T cells, having an effect on enhancing cell survival that was comparable to that of irradiated normal T cells cultured with IL-2 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Pretreatment with IL-2 enhances the survival of normal (upper panel) and CVID (lower panel) T cells after γ-irradiation. Normal or CVID T cells were cultured overnight and then kept either in the original medium, or in medium with recombinant 100 U/ml IL-2 added prior to irradiation. The data refer to five normal controls and eight CVID subjects. The boxes represent the range, the line inside the box represents the median value. (*P < 0·05; **P < 0·01 difference for IL-2-treated versus no IL-2-treated, significant for both groups).

Expression of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL

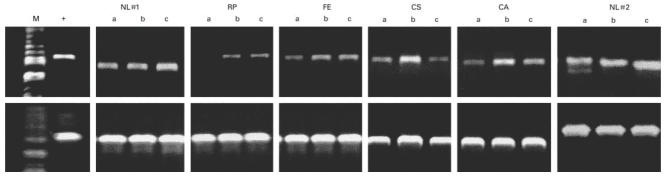

The intracellular levels of Bcl-2 for CD3+ T cells of 23 subjects with CVID varied widely, but were not overall significantly different from T cells of 10 normal controls. The median mean fluorescence intensity for CVID CD3+ T cells was 18·1 (range 10–24·6) versus 19·6 for controls (range 12·4–36·4). Bcl-xL gene expression after CD3 and CD3/CD28 costimulation was also examined. T cells of both CVID and normals had increased expression of bcl-xL mRNA in cultures stimulated by anti-CD3. While T cells of normal controls had augmented bcl-xL expression after CD3/CD28 costimulation, T cells of CVID subjects had no increase of bcl-xL mRNA under these conditions, suggesting dysregulation of the CD28 signalling pathway (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

T cells of CVID subjects were examined for up-regulation of bcl-xL gene expression, testing cells incubated with no stimulators, or with anti-CD3, or anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 in a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primers specific for bcl-xL or actin, as a sample control. The positive control was Jurkat cells transfected with bcl-x. The upper panel shows PCR results for two normals and four CVID subjects; a, no stimulation; b, CD3 stimulation; c, CD3 + CD28 stimulation. CVID subjects had enhanced bcl-xL expression after CD3 stimulation which was not augmented by addition of anti-CD28. The actin sample controls are shown (lower panels) for each. M, Molecular weight markers; +, positive control.

Discussion

In these studies we found that the T cells of about half of the CVID subjects studied displayed accelerated apoptosis in vitro, both with and without γ-irradiation. Whether this represents distinct subcategories of CVID is uncertain. Accelerated T cell apoptosis could underlie or contribute to a number of T cell defects characteristic of CVID, including lymphopenia [1,3], deficiency of antigen-specific T cells after immunization [34], reduced lymphocyte proliferation [4], and deficient cytokine secretion [13–15]. In the past several years, a number of investigators have examined the molecular factors that determine T cell survival; important amongst these are factors resulting from T cell antigen receptor cross-linking. Activation of T cells with either anti-TCR or anti-CD3 can enhance or maintain lymphocyte viability [30], or in some circumstances induce the onset of programmed cell death [35,36]. The differences in these outcomes can depend upon the presence of specific costimulatory influences, the best characterized being the CD28 receptor. CD28 costimulation markedly enhances cytokine production through transcriptional and post-translational regulation of cytokine gene expression, and promotes T cell survival by enhancing the expression of intracellular proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL [30,31]. Although previous work had concluded that CD28 receptor signalling was functional in CVID, since it enhanced DNA synthesis [26], CD28 coligation has not been found to normalize T cell responses to soluble antigens, nor significantly enhance IL-2, IL-4, IFN-γ or IL-10 production [27,28]. These observations suggest that some portions of the CD28 signalling pathways are abnormal in CVID. Our data show that while CD28 costimulation may increase the viability of irradiated normal T cells, it had no effect on enhancing the viability of CVID T cells.

CVID poor T cell viability in vitro could be due to lack of CD28 receptor-enhanced IL-2 secretion, resulting in cytokine deprivation, which under certain conditions can induce programmed cell death [37]. As previously demonstrated in CVID [27], we found a marked deficiency of IL-2 production for CVID T cells stimulated via the TCR and CD28 receptor. Washing irradiated normal human TCR/CD3-stimulated T cells, and placing them in medium without IL-2, also leads to a marked reduction in cell viability, a situation which is reversed by adding IL-2 [30,38]. Addition of IL-2 to irradiated CVID T cell cultures enhanced T cell survival as much as it did for T cells of normal subjects, suggesting that the interaction of IL-2 with its receptor is normal in CVID, and that lack of this cytokine is likely to be an important factor leading to poor T cell viability.

IL-2 deficiency could potentially lead to reduced expression of intracellular Bcl-2, an anti-apoptotic protein which is constitutively present in human T cells, and up-regulated by IL-2 [39]; a deficiency of Bcl-2 could lead to poor T cell viability. In virally infected humans, Bcl-2 expression is reduced, and correlated with apoptosis of T cells, especially T cells of the CD45RO phenotype [40]. Although the CD45RO population of T cells is generally expanded in CVID [41], we found that CVID T cell Bcl-2 expression appeared similar to that of T cells from normal control subjects, suggesting that a relative lack of Bcl-2 is not likely to contribute to poor viability of resting T cells. Our data agree with those of other authors, who noted increased T and B cell apoptosis in a subset of CVID subjects, together with an increased expression of Fas molecule which may contribute to the enhanced cell death, as noted in other congenital immunodeficiency diseases [42–44].

Another possibility is that Bcl-xL, a related mitochondrial membrane protein induced by T cell activation and important in T cell survival [30,31], might be insufficiently up-regulated in CVID. Since CD28 coligation normally up-regulates the expression of bcl-xL mRNA, the effects of CD28/TCR ligation on bcl-xL expression were examined. Bcl-xL message was up-regulated in CD3-stimulated CVID T cells, as for normal T cells tested under these conditions, but in contrast to normal T cells, addition of anti-CD28 had little or no effect on augmenting expression of bcl-xL. Defective up-regulation of bcl-xL could contribute to lack of T cell viability, as has been suggested for T cells of virally infected humans who also have been found to have deficient bcl-xL expression [40].

With abnormal T cell CD28 costimulation, T cell proliferation defects, and deficient IL-2 production, CVID bears some resemblance to the immune deficiencies of the CD28 gene knock-out mouse. Targeted disruption of CD28 in mice produces proliferation defects, IL-2 deficiency, poor T cell viability, serum immunoglobulin levels one-fifth of normal, and abnormal isotype switch from IgM to IgG, all features characteristic of CVID [45–47]. While we found that CD28 receptor triggering did not augment IL-2 production or enhance the viability of irradiated T cells, additional CD3 triggering defects are likely to be present, since anti-CD3 did not improve the viability of irradiated T cells to the degree found for normal T cells. Abnormalities of CVID TCR signalling have been previously described and could contribute to poor T cell survival [17,20]. Further understanding of the signalling pathways initiated via the T cell CD28 receptor in normal T cells will be needed before we can explore potential defects in CVID.

REFERENCES

- 1.Report of a WHO Scientific Group. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;109(Suppl.1):1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spickett GP, Farrant J, North ME, Zhang J, Morgan L, Webster Adb. Common variable immunodeficiency: how many diseases? Immunol Today. 1997;18:325–8. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sneller MC. Sneller MC, editor. Clinical spectrum of common variable immunodeficiency. New insights into common variable immunodeficiency. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:720–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-9-199305010-00011. Moderator. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cunningham-Rundles C, Bodian C. Common variable immunodeficiency: clinical and immunologic features of 248 patients. Clin Immunol. 1999;92:34–48. doi: 10.1006/clim.1999.4725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hermaszewski RA, Webster Adb. Primary hypogammaglobulinemia: a survey of clinical manifestations and complications. Q J Med. 1993;86:31–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mechanic L, Dickman S, Cunningham-Rundles C. Granulomatous disease in common variable immunodeficiency. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:613–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-8_part_1-199710150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saiki O, Ralph P, Cunningham-Rundles C, Good Ra. Three distinct stages of B-cell defect in common varied immunodeficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;79:6008–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.19.6008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bryant A, Calver NC, Toubi E, Webster ADB, Farrant J. Classification of patients with common variable immunodeficiency by B-cell secretion of IgM and IgG in response to anti-IgM and interleukin 2. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1990;56:239–48. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(90)90145-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saxon A, Sidell N, Zhang K. B cells from subjects with CVI can be driven to Ig production in response to CD40 stimulation. Cell Immunol. 1992;144:169–81. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(92)90234-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eisenstein EM, Chua K, Strober W. B cell differentiation defects in common variable immunodeficiency are ameliorated after stimulation with anti-CD40 antibody and IL10. J Immunol. 1994;152:5957–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright JJ, Wagner DK, Blaese RM, Hagengruber C, Waldmann TA, Fleisher Ta. Characterization of common variable immunodeficiency: identification of a subset of patients with distinct immunophenotypic and clinical features. Blood. 1990;76:2046–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.North ME, Spickett GP, Allsop J, Webster ADB, Farrant J. Defective DNA synthesis by T cells in acquired ‘common variable’ hypogammaglobulinemia on stimulation with mitogens. Clin Exp Immunol. 1989;76:19–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kruger G, Welte K, Ciobanu N, et al. Interleukin-2 correction of defective in vitro T cell mitogenesis in patients with common varied immunodeficiency. J Clin Immunol. 1984;4:295–303. doi: 10.1007/BF00915297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pastorelli G, Roncarolo MG, Touraine JL, Peronne G, Tovo PA, DeVries Je. Peripheral blood lymphocytes of patients with common variable immunodeficiency produce reduced levels of interleukin-4, interleukin-2 and interferon-gamma, but proliferate normally upon activation with mitogens. Clin Exp Immunol. 1989;78:334–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sneller MC, Strober W. Abnormalities of lymphokine gene expression in patients with common variable immunodeficiency. J Immunol. 1990;144:3762–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stagg AJ, Funauchi M, Knight SC, Webster ADB, Farrant J. Failure in antigen responses by T cells from patients with common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) Clin Exp Immunol. 1994;96:48–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06228.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fischer MB, Hauber J, Eggenbauer H, et al. A defect in the early phase of T-cell receptor-mediated T-cell activation in patients with common variable immunodeficiency. Blood. 1994;84:4234–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.North ME, Akbar AN, Borthwick N, Sagawa K, Funauchi M, Webster AD, Farrant J. Co-stimulation with anti-CD28 (Kolt-2) enhances DNA synthesis by defective T cells in common variable immunodeficiency. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;105:517–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06511.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.North ME, Webster AD, Farrant J. Primary defect in CD8+ lymphocytes in the antibody deficiency disease (common variable immunodeficiency): abnormalities in intracellular production of interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma) in CD28+ (‘cytotoxic’) and CD28−(‘suppressor’) CD8+ subsets. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;111:70–75. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00479.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fischer MB, Wolf HM, Hauber I, Eggenbauer H, Thon V, Sasgary M, Eibl M. Activation via the antigen receptor is impaired in T cells but not in B cells from patients with common variable immunodeficiency. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:231–41. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linsley PS, Ledbetter Ja. The role of the CD28 receptor during T cell responses to antigen. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11:191–212. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.001203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.June CH, Bluestone JA, Nadler LM, Thompson Cb. The B7 and CD28 receptor families. Immunol Today. 1994;15:321–31. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gimmi CD, Freeman GJ, Gribben JG, Sugita K, Freedman AS, Morimoto C, Nadler Lm. B-cell surface antigen B7 provides a costimulatory signal that induces T cells to proliferate and secrete interleukin 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:6575–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.15.6575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fraser JD, Irving BA, Crabtree GR, Weiss A. Regulation of interleukin-2 gene enhancer activity by the T cell accessory molecule CD28. Science. 1991;251:313–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1846244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jenkins MK, Taylor PS, Norton SD, Urdahl Kb. CD28 delivers a costimulatory signal involved in antigen-specific IL2 production by human T cells. J Immunol. 1991;147:2461–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.North ME, Akbar AN, Borthwick N, Sagawa K, Funauchi M, Webster AD, Farrant J. Costimulation with anti-CD28 (Kolt-2) enhances DNA synthesis by defective T cells in common variable immunodeficiency. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994;95:204–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06511.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fischer MB, Wolf HM, Eggenbauer H, et al. The costimulatory signal CD28 is fully functional but cannot correct the impaired antigen response in T cells of patients with common variable immunodeficiency. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994;95:209–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06512.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhuo Z, Huang R, Danon M, Mayer L, Cunningham-Rundles C. IL-10 production in common variable immunodeficiency. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1998;86:298–304. doi: 10.1006/clin.1997.4483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thon V, Wolf HM, Sasgary M, Litzman J, Samstag A, Hauber I, Lokai J, Eibl Mm. Defective integration of activating signals derived from the T cell receptor (TCR) and costimulatory molecules in both CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes of common variable immunodeficiency patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;110:174–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1997.tb08314.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boise LH, Minn AJ, Noel PJ, June CH, Accavitti MA, Lindstein T, Thompson Cb. CD28 costimulation can promote T cell survival by enhancing the expression of Bcl-xL. Immunity. 1995;3:87–98. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90161-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sperling AI, Auger JA, Ehst BD, Rulifson IC, Thompson CB, Bluestone Ja. CD28/B7 interactions deliver a unique signal to naive T cells that regulate cell survival but not early proliferation. J Immunol. 1996;157:3909–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCloskey TW, Oyaizu N, Coronesi M, Pahwa S. Use of flow cytometric assay to quantitate apoptosis in human lymphocytes. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1994;71:14–18. doi: 10.1006/clin.1994.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koester SK, Roth P, Mikulka WR, Schlossman SF, Zhang C, Bolton We. Monitoring early cellular response in apoptosis is aided by the mitochondrial membrane protein-specific monoclonal antibody APO2.7. Cytometry. 1997;29:306–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kondratenkto I, Amlot N, Webster AD, Farrant J. Lack of specific antibody response in common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) associated with failure in production of antigen-specific memory T cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;108:9–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.d01-993.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klas C, Debatin KM, Jonker RR, Krammer Ph. Activation interferes with the APO-1 pathway in mature human T cells. Int Immunol. 1993;5:625–30. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.6.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Owen-Schaub LB, Yonehar S, Crump WL, Grimm Ea. DNA fragmentation and cell death is electively triggered in activated human lymphocytes by Fas antigen engagement. Cellular Immunol. 1992;140:197–205. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(92)90187-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neito MA, Gonzalez A, Lopez-Rivas A, Diaz-Espada F, Gambon F. IL-2 protects against anti-CD3-induced cell death in human medullary thymocytes. J Immunol. 1990;145:1364–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boise LH, Minn AJ, June CH, Lindsten T, Thompson Cb. Growth factors can enhance lymphocyte survival without committing the cell to undergo cell division. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5491–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gomez J, Martinez AC, Gonzalez A, Garcia A, Rebollo A. The Bcl-2 gene is differentially regulated by IL-2 and IL-4: role of the transcription factor NF-AT. Oncogene. 1998;10:1235–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akbar AN, Borthwick N, Salmon M, et al. The significance of low bcl-2 expression by CD45RO T cells in normal individuals and patients with acute viral infections. The role of apoptosis in T cell memory. J Exp Med. 1993;178:427–38. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.2.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baumert E, Wolff-Vorbeck G, Schlesier M, Peter Hh. Immunophenotypical alterations in a subset of patients with common variable immunodeficiency. Clin Exp Immunol. 1992;90:25–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb05826.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iglesias J, Matamoros N, Raga S, Ferrer JM, Mila J. CD95 expression and function on lymphocyte subpopulations in common variable immunodeficiency (CVID); related to increased apoptosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;117:138–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00946.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saxon A, Keld B, Diaz-Sanchez D, Guo BC, Sidell N. B cells from a distinct subset of patients with common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) have increased CD95 (Apo-1/fas), diminished CD38 expression, and undergo enhanced apoptosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;102:17–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb06630.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brugnoni D, Airo P, Facchetti F, Blanzuoli L, Ugazio AG, Cattaneo R, Notarangelo Ld. In vitro cell death of activated lymphocytes in Omenn's syndrome. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2765–73. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shahinian A, Pfeffer K, Lee KP, et al. Differential T cell costimulatory requirements in CD28-deficient mice. Science. 1993;261:609–12. doi: 10.1126/science.7688139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Green JM, Noel PJ, Sperling AI, Walunas TL, Gray GS, Bluestone JA, Thompson Cb. Absence of B7-dependent responses in CD28-deficient mice. Immunity. 1994;1:501–8. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lucas PJ, Negishi I, Nakayama K, Fields LE, Loh Dy. Naive CD28-deficient T cells can initiate but not sustain an in vitro antigen-specific immune response. J Immunol. 1995;154:5757–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]