Abstract

IFN-α administration after primary tumour resection improves the survival of melanoma patients at high risk of relapse. To investigate whether this response might be due to stimulation of anti-tumour immunity, the effect of IFN-α on anti-melanoma CTL generation in MLTC was measured. IFN-α increased both allogeneic and autologous anti-melanoma CTL generation from peripheral blood lymphocytes stimulated with irradiated primary melanoma cultures. IFN-α up-regulated MHC class I expression on primary melanoma cultures, whereas IFN-γ up-regulated both MHC class I and II expression. However, the effect of IFN-α on anti-melanoma CTL generation was often more potent than that of IFN-γ, equalling the effect of the optimal combination of IL-2 and IL-12. Pre-treatment of primary melanoma cultures with IFN-γ was sufficient for CTL generation in MLTC, whereas IFN-α needed to be present during the MLTC. While direct anti-proliferative effects of IFN-α on some tumour cells have been described, IFN-α did not inhibit proliferation of primary melanoma cultures. These results suggest that the clinical effects of IFN-α in melanoma patients may be immune-mediated.

Keywords: IFN-α, cytotoxic T cell, melanoma

INTRODUCTION

It has been recognized for many years that melanoma is an immunogenic tumour and immunotherapy has been used to treat patients since the turn of the century. More recently, various potential immunostimulatory treatments have shown anti-melanoma activity [1]. Most of these agents have not altered the survival of patients with metastatic disease, but high dose IFN-α-2B given following primary tumour resection improved the survival of melanoma patients at risk of relapse [2].

There are many effects of type 1 IFNs (α or β) on the immune system. First, IFN-α or -β have been shown to up-regulate MHC class I expression in many cell types in culture including human monocytes [3], keratinocytes [4] and endothelial cells [5]. Furthermore, administration of IFN-α to mice up-regulated MHC class I in many tissues [6] and IFN-α administration to melanoma patients has been shown to up-regulate MHC class I expression on peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) [7]. IFN-α and -β have also been shown to up-regulate MHC class I on cultures of human melanoma cells [8,9]. All of these studies contrasted the action of type 1 IFNs with the type II IFN-γ. Type 1 IFNs tend to induce only MHC class I expression, whereas IFN-γ induces both MHC class I and class II in many cell types including melanoma [8,9]. Another effect of type I IFN on the immune system is the induction of polyclonal proliferation of CD8+ cells [10]. This probably serves to mobilize a large cohort of potential CTL during viral infection. IFN-α also enhanced Th1 cytokine responses when added to CD4+ cells [11] and when used to treat bladder cancer patients in combination with bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) [12].

Our knowledge of melanoma recognition by the immune system has advanced rapidly in the last few years. Experiments pioneered by Boon and colleagues have identified a number of peptides presented by MHC class I on melanoma cells, which can be recognized by autologous CTL (reviewed in [13]). There is also indirect evidence to support the hypothesis that anti-melanoma CTL in patients can control tumour growth. For example, metastases which appeared in patients treated with immunotherapy have lost expression of antigen/MHC class I combinations recognized by dominant CTL [14]. Evidence is more conclusive in mice, where cells with increased tumourigenicity have been shown to be variants which have lost CTL antigens [15]. IFN-α gene transfer to mouse tumours resulted in their rejection, which required CD8+ T cells [16,17]. Such tumour cells secreting IFN-α have been shown to stimulate proliferation of memory phenotype CD8+ cells in mice [18]. Because of this suggestion that IFN-α enhances generation of anti-tumour CTL in mice, our aim was to determine whether IFN-α could stimulate generation of anti-melanoma CTL from human lymphocytes incubated with primary cultures of melanoma cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

The primary melanoma cultures JB, JT and BS were isolated from metastatic melanoma biopsies as part of a melanoma gene therapy clinical trial (described in [19], from patients 11, 10 and 9, respectively). They were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Gibco, Paisley, UK), penicillin 100 μ g/ml, and streptomycin 100 μ g/ml. Peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) were isolated from heparinized venous blood from healthy donors, or the melanoma patient JT 6 weeks after three irradiated IL-2-secreting tumour cell vaccinations [19], by Ficoll–Hypaque (Lymphoprep; Nycomed Labs, Oslo, Norway) gradient centrifugation at 580 g for 20 min followed by extensive washing. K562 is a human leukaemia cell line [20] which is used as a highly sensitive natural killer (NK) cell target.

Cell-mediated cytotoxicity assays

PBL stimulations were performed in RPMI 1640 with 10% heat-inactivated human AB serum (Sera-Lab, Oxford, UK), penicillin 100 μ g/ml, streptomycin 100 μ g/ml and 3 mm glutamine as previously described [21]. Allogeneic or autologous PBL (106/ml) were incubated for 10 days with irradiated melanoma cells (100 Gy) at a ratio of 40:1. IL-2 (Eurocetus, Harefield, UK) plus IL-12 (R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK), IFN-α-2B (Intron A; Schering Corp., Kenilworth, NJ) or IFN-γ (R&D Systems) were added to the cultures on days 0, 3, 6 and 9 as indicated. On day 10, the killing of melanoma cells was measured by incubation of PBL with Na(51Cr)O4-labelled melanoma cells (2·5 × 103/well) for 4 h, then determination of cell-associated and released radioactivity. Maximum lysis was defined as the radioactivity released by 5% Nonidet-P40. Spontaneous lysis, defined as that observed after incubation Na(51Cr)O4-labelled melanoma cells in the absence of PBL for 4 h, was subtracted from all measurements. Values shown are the mean (± s.e.m.) of triplicate determinations. Where indicated, 50-fold excess K562 cells were added to inhibit NK killing of the melanoma cells [20]. Where indicated, anti-CD3 (UCHT1; Dako, High Wycombe, UK) plus anti-CD8 (Leu-2B; Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) were incubated with the PBL at a 1:10 dilution of each antibody for 30 min at 37°C before the killing assay to block T cell receptor-mediated killing. Where indicated, the melanoma target cells were preincubated for 24 h in medium containing IFN-γ (50 U/ml) before the killing assay to up-regulate MHC expression.

Flow cytometric analysis

Cells were incubated for 30 min at 4°C with a 1:50 dilution of anti-MHC class I (M736; Dako), or anti-MHC class II (MCA477; Serotec, Oxford, UK), or no antibody in PBS with 2% FCS. They were then washed twice with PBS/2% FCS, then incubated with FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulins (1:50 dilution) for a further 30 min at 4°C. After two washes with PBS −2% FCS, propidium iodide was added to allow elimination of dead cells during acquisition. The fluorescence of the stained cells was then analysed using Lysis II software on a FACScan.

RESULTS

IFN-α stimulates allogeneic anti-melanoma CTL generation

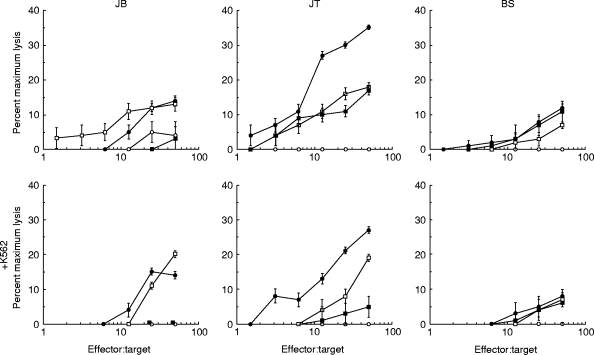

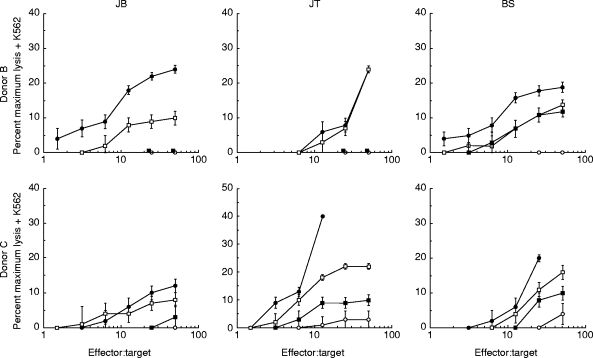

PBL from a single healthy donor (A) were incubated with irradiated primary melanoma cultures for 10 days. IFN-α or IFN-γ were added every 3 days to some cultures and their effect was compared with addition of IL-2 plus IL-12, which we have previously shown to be very potent in the generation of anti-melanoma CTL [21]. IFN-α-2B was added at the high dose of 1000 U/ml, to mimic the clinical level in melanoma therapy. At the end of 10 days the ability of the PBL to kill each melanoma was measured. Figure 1 (upper panels) shows that IFN-α was a potent stimulator of anti-melanoma lytic activity. For one melanoma, JB, IFN-α was effective whereas IFN-γ was not. When the NK cell target K562 was added to the killing assay to inhibit NK cell-mediated lysis, a considerable fraction of the IFN-α cytolytic activity remained (Fig. 1, lower panels), demonstrating that IFN-α stimulated both NK and CTL generation. Figure 2 shows that similar results were obtained with two further PBL donors (B and C), IFN-α-stimulated lytic activity in all cultures; again, a fraction of this lytic activity was not blocked by K562 cells, demonstrating both NK and CTL generation. IFN-γ was ineffective in cultures with the melanoma JB. To confirm that the lytic activity that we observed in the presence of K562 cells was mediated by CTL, we used a combination of anti-CD3 and anti-CD8 antibodies to block the activity. A typical result, for donor A PBL incubated with melanoma JT plus IFN-α, is shown in Fig. 3. This shows that essentially all the lytic activity observed in the presence of K562 cells was due to a T cell receptor-mediated mechanism.

Fig. 1.

IFN-α stimulates the generation of allogeneic anti-melanoma CTL. Peripheral blood lymphocytes from a healthy donor (donor A) were cultured for 10 days with irradiated primary cultures of melanoma cells JB, JT or BS as described in Materials and Methods. The cytokines IL-2 (10 U/ml) + IL-12 (300 pg/ml), IFN-α (1000 U/ml) or IFN-γ (50 U/ml) were added on days 0, 3, 6 and 9 of the cultures as indicated. On day 10 the ability of the cultured lymphocytes to lyse the same melanoma cells labelled with 51Cr was measured as described in Materials and Methods. These target cells were preincubated for 24 h in medium containing IFN-γ (50 U/ml) before the killing assay. The killing assay was also performed in the presence of excess unlabelled K562 cells (× 50; lower panels). ○, Nil; •, IL-2 + IL-12; □, IFN-α;▪, IFN-γ.

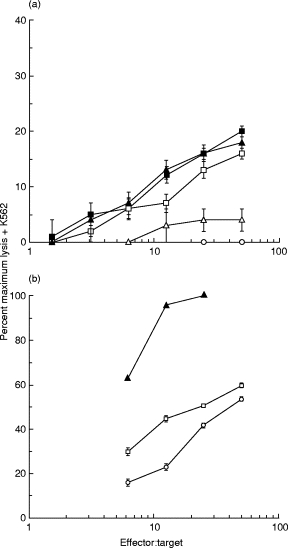

Fig. 2.

IFN-α stimulates anti-melanoma CTL generation in six allogeneic cultures. Peripheral blood lymphocytes from two further healthy donors (B and C) were cultured for 10 days with irradiated primary cultures of melanoma cells JB, JT or BS as described in Materials and Methods. The cytokines IL-2 (10 U/ml) + IL-12 (300 pg/ml), IFN-α (1000 U/ml) or IFN-γ (50 U/ml) were added on days 0, 3, 6 and 9 of the cultures as indicated. On day 10 the ability of the cultured lymphocytes to lyse the same melanoma cells labelled with 51Cr was measured as described in Materials and Methods. These target cells were preincubated for 24 h in medium containing IFN-γ (50 U/ml) before the killing assay. The killing assay was performed in the presence of excess unlabelled K562 cells (× 50). ○, Nil; •, IL-2 + IL-12; □, IFN-α;▪, IFN-γ.

Fig. 3.

Anti-CD3/CD8 blocking of IFN-α-stimulated anti-melanoma CTL. Peripheral blood lymphocytes from donor A were cultured for 10 days with irradiated primary cultures of melanoma cells JT as described in Materials and Methods. IFN-α (1000 U/ml) was added on days 0, 3, 6 and 9 of the culture. On day 10 the ability of the cultured lymphocytes to lyse the melanoma cells labelled with 51Cr was measured as described in Materials and Methods. The target cells were preincubated for 24 h in medium containing IFN-γ (50 U/ml) before the killing assay. The killing assay was performed in the presence of excess unlabelled K562 cells (× 50). Some of the lymphocytes were incubated for 30 min at 37°C with a combination of anti-CD3 and anti-CD8 MoAbs as indicated before the killing assay, the remainder were incubated in 10% mouse serum. □, IFN-α;▴, IFN-α+ anti-CD3/anti-CD8.

Effects of IFN-α on the melanoma cells

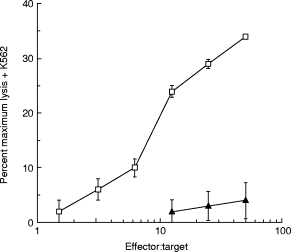

To examine the possible mechanisms by which IFN-α could stimulate CTL generation, we first examined MHC class I and class II expression by the primary melanoma cultures. Figure 4 shows that cultures JT and BS expressed high levels of MHC class I and that this was further up-regulated by treatment with either IFN-α or IFN-γ. IFN-γ also up-regulated MHC class II expression on cultures JT and BS, whereas IFN-α did not (Fig. 4). This difference in regulation of MHC class II expression by IFN-γ and IFN-α has previously been reported for a number of cell types including melanoma [8,9]. Interestingly, the melanoma culture JB expressed little MHC class I or class II and only slight up-regulation by IFN-α or IFN-γ was observed (Fig. 4). This was the culture in which IFN-γ was ineffective in the stimulation of CTL generation. However, the level of MHC class I expression by JB was clearly sufficient to allow allogeneic CTL-mediated lysis (Figs 1 and 2). Differences in MHC antigen expression by murine tumours has been shown to be due to autocrine IFN production [22], However, we did not detect autocrine IFN secretion by any of the melanoma cultures (data not shown). As IFN-α exerts anti-proliferative effects on a wide variety of tumour cell types, we also examined its effect on the growth of the primary melanoma cultures and demonstrated that neither IFN-α nor IFN-γ affected the growth of the three melanoma cultures used in this study (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

IFN-α up-regulates MHC class I expression. Primary cultures of melanoma cells JB, JT or BS were untreated, or treated with IFN-α (1000 U/ml) or IFN-γ (50 U/ml) for 48 h as indicated. MHC class I and II expression was then analysed using a FACScan by staining with either nothing (black), a mouse anti-MHC class I MoAb (red) or a mouse anti-MHC class II MoAb (green), followed by an FITC-labelled goat anti-mouse antiserum. Mean fluorescence shift, defined as mean fluorescence with anti-MHC class I or II antibody plus FITC-labelled goat anti-mouse antiserum minus mean fluorescence with FITC-labelled goat anti-mouse antiserum alone, was as follows: JB, MHC I, 3·1, MHC II, 0; JB + IFN-α, MHC I, 11·2, MHC II, 2·7; JB + IFN-γ, MHC I, 9·4, MHC II, 10·5; JT, MHC I, 970, MHC II: 0; JT + IFN-α, MHC I, 1400, MHC II, 7·8; JT + IFN-γ, MHC I, 1500, MHC II, 53; BS, MHC I, 630, MHC II, 0; BS + IFN-α, MHC I, 920, MHC II, 13; BS + IFN-γ, MHC I, 990, MHC II, 77.

The results shown in Figs 1, 2 and 4 suggest that IFN-γ might be stimulating CTL generation by up-regulating MHC expression on the melanoma cells during their co-culture with the PBL. This could be hypothesized from the lack of stimulation of CTL generation by IFN-γ in the JB co-cultures, where MHC expression was only slightly up-regulated. To test this idea, we pretreated the melanoma JT with either IFN-γ or IFN-α to up-regulate MHC expression, then set up the PBL co-culture. Figure 5a shows that the full effect of IFN-γ was observed by pretreating the melanoma cells. However, much of the effect of IFN-α was lost when the melanoma cells were pretreated (Fig. 5a), demonstrating that IFN-α also needed to act on the PBL. A direct effect of IFN-α on the PBL in the melanoma co-culture could also be inferred from the experiment of Fig. 5b. Here the ability of IFN-α-treated JT melanoma cells to act as targets was shown to be less than that of IFN-γ-treated cells. This could be ascribed to the lower MHC class I up-regulation and the lack of MHC class II up-regulation on these cells by IFN-α. However IFN-α was fully active in generating allogeneic CTL against these cells (Figs 1 and 2).

Fig. 5.

Effect of IFN-α pretreatment of melanoma cells on anti-melanoma CTL generation and melanoma cell killing. (a) Peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) from donor A were cultured for 10 days with irradiated primary cultures of melanoma cells JT. IFN-α (1000 U/ml) or IFN-γ (50 U/ml) were either used to treat the melanoma cells for 48 h before the co-culture (indicated as Pretreat) or added on days 0, 3, 6 and 9 of the cultures. On day 10 the ability of the cultured lymphocytes to lyse the melanoma cells labelled with 51Cr was measured as described in Materials and Methods. These target cells were preincubated for 24 h in medium containing IFN-γ (50 U/ml) before the killing assay. This assay was performed in the presence of excess unlabelled K562 cells (× 50). ○, Nil; Δ, pretreat IFN-α;□, IFN-α;▴, pretreat IFN-γ;▪, IFN-γ. (b) PBL from donor A were cultured for 10 days with irradiated primary cultures of melanoma cells JT and IFN-α (1000 U/ml) was added on days 0, 3, 6 and 9 of the culture. On day 10 the ability of the cultured lymphocytes to lyse melanoma cells labelled with 51Cr was measured as described in Materials and Methods. This assay was performed in the presence of excess unlabelled K562 cells (× 50). The target melanoma cells were either untreated, or pretreated with IFN-α (1000 U/ml) or IFN-γ (50 U/ml) for 48 h before the killing assay as indicated. ○, Untreated target; □, IFN-α target; ▴, IFN-γ target.

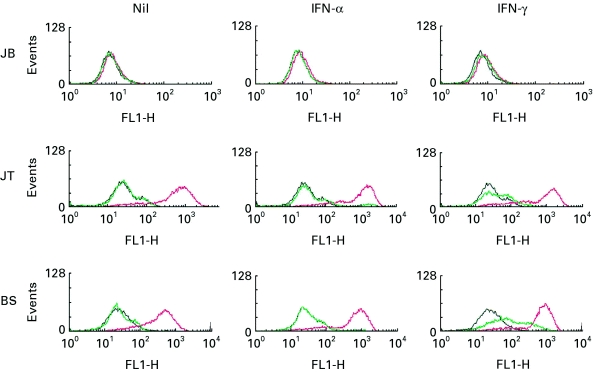

IFN-α stimulates autologous anti-melanoma CTL generation

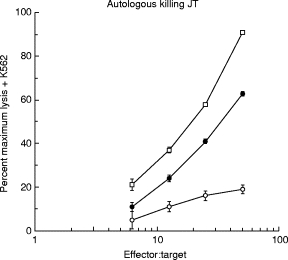

The level of anti-tumour CTL that can be generated from the PBL of most metastatic melanoma patients is low, or undetectable [19,21]. Therefore, to examine the effect of IFN-α on CTL generation in autologous MLTC, we used PBL from patient JT. This patient was treated with three vaccinations of irradiated autologous melanoma cells secreting IL-2 as part of a Phase I/II cancer gene therapy trial. After the second vaccination, high levels of anti-melanoma CTL were detected in the PBL of JT, and this level was maintained [19]. Figure 6 shows the results of PBL from JT taken 6 weeks after the third tumour vaccine, then cultured with autologous JT tumour cells. In these cultures IFN-α stimulated the generation of autologous anti-melanoma CTL (Fig. 6), proving at least as effective as the combination of IL-2 plus IL-12. A similar result was obtained with a second post-vaccination sample of JT PBL; because of limited cell numbers the effect of IFN-γ was not tested in these cultures.

Fig. 6.

IFN-α stimulates the generation of autologous anti-melanoma CTL. Peripheral blood lymphocytes from a melanoma patient (JT) were cultured for 10 days with irradiated primary cultures of autologous melanoma JT, as described in Materials and Methods. The cytokines IL-2 (10 U/ml) + IL-12 (300 pg/ml) or IFN-α (1000 U/ml) were added on days 0, 3, 6 and 9 of the cultures as indicated. On day 10 the ability of the cultured lymphocytes to lyse the same melanoma cells labelled with 51Cr was measured as described in Materials and Methods. The target cells were preincubated for 24 h in medium containing IFN-γ (50 U/ml) before the killing assay. This assay was performed in the presence of excess unlabelled K562 cells (× 50). ○, Nil; •, IL-2 + IL-12; □, IFN-α.

DISCUSSION

This study has demonstrated that IFN-α can stimulate the generation of both allogeneic and autologous anti-melanoma CTL from PBL cultured with irradiated melanoma cells. This effect of IFN-α may be partly due to MHC class I up-regulation on the melanoma cells, or up-regulation of other cell surface molecules such as intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1). Indeed, IFN-α activates both STAT1 and STAT2 in melanoma cell lines and tumour samples [23] which may regulate expression of a number of target genes. However, direct action of the IFN-α on the PBL is also required for optimal CTL generation in culture. A similar increase in CTL generation from PBL by IFN-α was shown in a study where IFN-α was added to PBL cultured with dendritic cells transfected with melanoma antigens [24]. Together these results suggest that IFN-α may be usefully combined with either tumour cell or antigen-presenting cell vaccination therapies for melanoma. The mechanism by which IFN-α acts on PBL to augment CTL generation remains to be determined. It might be due to IFN-α’s reported stimulation of Th1 cytokine production [11], or to a direct effect on CD8+ cell survival or proliferation [10]. It is also possible that IFN-α augments T cell cytotoxicity, as a recent report describes up-regulation of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) by IFN-α on activated T cells which makes them cytotoxic towards renal cell carcinoma [25].

It is possible that high dose IFN-α-2B therapy of melanoma patients at risk of relapse [2] is effective because it stimulates generation of anti-melanoma CTL which eliminate micrometastases. However, it is also clear that IFN-α can exert a number of effects in these circumstances. For example, IFN-α treatment has been shown to down-regulate TNF-α expression in patient metastases, which may enhance immune infiltration [26]. Nor are the effects of IFN-α necessarily immunostimulatory. IFN up-regulation of MHC expression on melanoma cells has also been shown to make them resistant to NK cell lysis [27]. There is also evidence for differential regulation of HLA-A and HLA-B alleles by IFN-α[28]. This complex interplay between CTL and NK cell sensitivity may explain the variation in efficacy of IFN-α therapy between patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Cancer Research Campaign. M.H. is the recipient of a Cancer Research Campaign research fellowship for a clinician.

References

- 1.Bridgewater JA, Gore ME. Biological response modifiers in melanoma. Br Med Bull. 1995;51:656–77. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirkwood JM, Strawderman MH, Ernstoff MS, Smith TJ, Borden EC, Blum RH. Interferon alfa-2b adjuvant therapy of high-risk resected cutaneous melanoma: the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trial EST 1684. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:7–17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rhodes J, Ivanyi J, Cozens P. Antigen presentation by human monocytes: effects of modifying major histocompatibility complex class II antigen expression and interleukin 1 production by using recombinant interferons and corticosteroids. Eur J Immunol. 1986;16:370–5. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830160410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niederwieser D, Aubock J, Troppmair J, et al. IFN-mediated induction of MHC antigen expression on human keratinocytes and its influence on in vitro alloimmune responses. J Immunol. 1988;140:2556–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lapierre LA, Fiers W, Pober JS. Three distinct classes of regulatory cytokines control endothelial cell MHC antigen expression. Interactions with immune gamma interferon differentiate the effects of tumor necrosis factor and lymphotoxin from those of leukocyte alpha and fibroblast beta interferons. J Exp Med. 1988;167:794–804. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.3.794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halloran PF, Urmson J, Van der Meide PH, Autenried P. Regulation of MHC expression in vivo. II. IFN-alpha/beta inducers and recombinant IFN-alpha modulate MHC antigen expression in mouse tissues. J Immunol. 1989;142:4241–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giacomini P, Fraioli R, Calabro AM, Di Filippo F, Natali PG. Class I major histocompatibility complex enhancement by recombinant leukocyte interferon in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells and plasma of melanoma patients. Cancer Res. 1991;51:652–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giacomini P, Gambari R, Barbieri R, et al. Regulation of the antigenic phenotype of human melanoma cells by recombinant interferons. Anticancer Res. 1986;6:877–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nistico P, Tecce R, Giacomini P, Cavallari A, D’Agnano I, Fisher PB, Natali PG. Effect of recombinant human leukocyte, fibroblast, and immune interferons on expression of class I and II major histocompatibility complex and invariant chain in early passage human melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 1990;50:7422–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tough DF, Borrow P, Sprent J. Induction of bystander T cell proliferation by viruses and type I interferon in vivo. Science. 1996;272:1947–50. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brinkmann V, Geiger T, Alkan S, Heusser CH. Interferon alpha increases the frequency of interferon gamma-producing human CD4 + T cells. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1655–63. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.5.1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luo Y, Chen X, Downs TM, DeWolf WC, O’Donnell MA. IFN-alpha 2B enhances Th1 cytokine responses in bladder cancer patients receiving Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin immunotherapy. J Immunol. 1999;162:2399–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boon T, Coulie PG, Van den Eynde B. Tumor antigens recognized by T cells. Immunol Today. 1997;18:267–8. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)80020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ikeda H, Lethe B, Lehmann F, et al. Characterization of an antigen that is recognized on a melanoma showing partial HLA loss by CTL expressing an NK inhibitory receptor. Immunity. 1997;6:199–208. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80426-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van den Eynde B, Lethe B, Van Pel A, De Plaen E, Boon T. The gene coding for a major tumor rejection antigen of tumor P815 is identical to the normal gene of syngeneic DBA/2 mice. J Exp Med. 1991;173:1373–84. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.6.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrantini M, Giovarelli M, Modesti A, et al. IFN-alpha 1 gene expression into a metastatic murine adenocarcinoma (TS/A) results in CD8 + T cell-mediated tumor rejection and development of antitumor immunity. Comparative studies with IFN-gamma-producing TS/A cells. J Immunol. 1994;153:4604–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coleman M, Muller S, Quezada A, et al. Nonviral interferon alpha gene therapy inhibits growth of established tumors by eliciting a systemic immune response. Hum Gene Ther. 1998;9:2223–30. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.15-2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belardelli F, Ferrantini M, Santini SM, Baccarini S, Proietti E, Colombo MP, Sprent J, Tough DF. The induction of in vivo proliferation of long-lived CD44hi CD8 + T cells after the injection of tumor cells expressing IFN-alpha1 into syngeneic mice. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5795–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palmer K, Moore J, Everard M, et al. Gene therapy with autologous, interleukin 2-secreting tumor cells in patients with malignant melanoma. Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10:1261–8. doi: 10.1089/10430349950017941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coulie PG, Somville M, Lehmann F, Hainaut P, Brasseur F, Devos R, Boon T. Precursor frequency analysis of human cytolytic T lymphocytes directed against autologous melanoma cells. Int J Cancer. 1992;50:289–97. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910500220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Wit D, Flemming CL, Harris JD, Palmer KJ, Moore JS, Gore ME, Collins MK. IL-12 stimulation but not B7 expression increases melanoma killing by patient cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;105:353–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-773.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nanni P, Landuzzi L, Nicoletti G, De Giovanni C, Giovarelli M, Lalli E, Facchini A, Lollini PL. Control of H-2 expression in transformed nonhaemopoietic cells by autocrine interferon. Br J Cancer. 1992;66:479–82. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1992.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carson WE. IFN-alpha-induced activation of STATs in malignant melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:2219–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tuting T, Wilson CC, Martin DM, et al. Autologous human monocyte-derived dendritic cells genetically modified to express melanoma antigens elicit primary cytotoxic T cell responses in vitro: enhancement by cotransfection of genes encoding the Th1-biasing cytokines IL-12 and IFN-alpha. J Immunol. 1998;160:1139–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kayagaki N, Yamaguchi N, Nakayama M, Eto H, Okumura K, Yagita H. Type I interferons (IFNs) regulate tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) expression on human T cells: a novel mechanism for the antitumor effects of type I IFNs. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1451–60. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.9.1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hakansson A, Gustafsson B, Krysander L, Bergenwald C, Sander B, Hakansson L. Effect of IFN-alpha on the expression of TNF-alpha by metastatic melanoma patients. Melanoma Res. 1997;7:139–45. doi: 10.1097/00008390-199704000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pende D, Accame L, Pareti L, Mazzocchi A, Moretta A, Parmiani G, Moretta L. The susceptibility to natural killer cell-mediated lysis of HLA class I-positive melanomas reflects the expression of insufficient amounts of different HLA class I alleles. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:2384–94. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199808)28:08<2384::AID-IMMU2384>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hakem R, Le Bouteiller P, Jezo-Bremond A, Harper K, Campese D, Lemonnier FA. Differential regulation of HLA-A3 and HLA-B7 MHC class I genes by IFN is due to two nucleotide differences in their IFN response sequences. J Immunol. 1991;147:2384–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]