Abstract

To elucidate the pathogenic mechanisms of human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1)-associated lung inflammation, we conducted a histopathological and molecular analysis study using transgenic mice bearing pX region of this virus. In these mice, accumulations of inflammatory cells consisting mainly of lymphocytes were present in peribronchiolar and perivascular areas and alveolar septa, while control littermate mice did not show such changes. In situ hybridization showed that the anatomic distribution of p40tax mRNA was similar to that of inflammatory cells, typically in peribronchiolar areas and to a lesser extent in perivascular and alveolar septa. Inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, tumour necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma, and several chemokines, such as monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), RANTES, macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α) and IP-10, were detected in lungs of transgenic mice but not control mice. Semiquantitative analysis using reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction showed a significant correlation between MCP-1 mRNA expression and p40tax mRNA, but not with other chemokines. The gene expression of the above chemokines, with the exception of MIP-1α, correlated with the severity of histopathological changes in the lung. Considered together, our results suggested that p40tax synthesis may be involved in the development of lung lesions caused by HTLV-1 through the induction of local production of chemokines.

Keywords: HTLV-1, lung disease, Tax, chemokines, inflammatory cytokines

Introduction

Human T lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) is the aetiological agent of adult T-cell leukaemia (ATL) [1,2] and HTLV-1-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP) [3,4]. ATL is a neoplastic disease characterized by monoclonal expansion of HTLV-1-transformed cells, whereas HAM/TSP is thought to be caused by immunological reaction to infected CD4+ T cells in the central nervous system. Recently, many other clinical conditions have been considered to be associated with HTLV-1 infection, including uveitis [5], arthropathy [6] and inflammatory pulmonary diseases [7,8].

The possible relationship between HTLV-1 infection and pulmonary involvement was initially raised in a report demonstrating the presence of lymphocytosis and HTLV-1-infected T cells in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) of patients with HAM/TSP compared with healthy carriers without any other diseases [7]. Subsequent studies have shown a close correlation between viral mRNA expression and lymphocytosis in the lungs of these patients [9,10]. It is postulated that HTLV-1 infection and its expression may cause activation of intrapulmonary lymphocytes and development of cellular inflammatory lesions in the lungs.

The protein product of HTLV-1 pX gene, p40tax, is a potent transcriptional activator, which enhances not only replication of the virus itself but also the expression of various normal cellular genes, such as IL-2, IL-2R, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), c-jun and c-fos, which are known to be involved in cellular growth and immune reactions [1]. Thus, p40tax is suspected to play an important role in the pathogenesis of diseases caused by HTLV-1. To elucidate the involvement of HTLV-1 infection in pulmonary inflammatory diseases, we recently used transgenic mice bearing the gene segment of HTLV-1 including the env and pX regions, a model previously established by Iwakura and co-workers [11]. These mice express p40tax mRNA in various tissues, including joints, brain, muscles and lungs, and exhibit clinical and histopathological findings of arthritis [11]. We have recently shown that these mice also exhibited histopathological changes, characterized by accumulation of inflammatory cells in the lungs, especially in peribronchiolar and perivascular areas and in alveolar septa, and that these changes correlated with the expression of p40tax in the lungs [12]. These findings suggested that p40tax might be involved in the pathogenesis of HTLV-1-associated pulmonary inflammatory diseases. However, the precise mechanism remains to be elucidated.

Recent studies have demonstrated the important role of a variety of chemoattracting cytokines in the development of various inflammatory lesions with infiltration of leucocytes [13,14] and the regulatory role of several inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), in the production of certain chemokines [15]. Using cultured human T cell lines, Baba and co-workers [16] indicated that p40tax was involved in the production of various chemokines.

As an extension to our recent findings [12], the aim of the present study was to compare the distribution of p40tax gene expression in the lungs with the histopathological changes in transgenic mice. Furthermore, we also examined the correlation between expression of inflammatory cytokine and chemokine mRNAs and that of p40tax mRNA as well as the distribution of inflammatory cells in the lungs.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Animals

Transgenic mice with HTLV-1 env-pX region of the viral genome including its own long-terminal repeat promoter were employed. Original transgenic mice with C3H/HeN background were backcrossed with BALB/c mice. Mice of 10–11 generations after backcrossing were used in the present experiments. The transgene was detected through dot blot hybridization using DNA prepared from mouse tails. Littermate mice were used as controls. The experimental protocol was approved by the Ethics Review Committee for Animal Experimentation of our university. All mice were housed in a pathogen-free environment and received sterilized food and water at the Laboratory Animal Centre for Biomedical Science in University of the Ryukyus.

Histopathological examination

Mice were killed at 7, 11 and 26 weeks of age and the middle and lower lobes of the right lung were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS at room temperature overnight and embedded in paraffin by standard procedures. Sections (3 μm) were prepared and placed on glass slides, stained with haematoxylin–eosin (H–E) and examined under a light microscope.

Preparation of pulmonary intraparenchymal leucocytes

The chest was opened, and the pulmonary vascular bed was flushed by injecting 2 or 3 ml of chilled physiological saline into the right ventricle. The lungs were then excised and washed in RPMI 1640/10 mm HEPES. After teasing with stainless mesh, the lungs were incubated in RPMI 1640 with 5% of fetal calf serum (FCS; Whitakker, Walkersville, MD), 100 U/ml penicillin G, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 10 mm HEPES, 50 mm 2-mercaptoethanol and 2 mm l-glutamine, containing 20 U/ml collagenase (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO) and 1 μg/ml DNase I (Sigma). A volume of 10 ml was used for one set of lungs. After incubation for 60 min at 37°C with vigorous shaking, tissue fragments and the majority of dead cells were removed by passing through the 50-μm nylon mesh. After centrifugation, the pellet was resuspended in 4 ml of 40% (v/v) Percoll (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) and layered onto 4 ml of 80% (v/v) Percoll. After centrifugation at 600 g for 20 min at 15°C, the cells at the interface were collected, washed twice and counted using a haemocytometer. Cells were centrifuged onto a glass slide and stained using a May–Giemsa technique. At least 500 cells were examined for differential of cellular fraction by photomicroscopic observation.

Quantitative analysis of severity of lung lesions

For quantification of the pathological changes, light microscopic images of the total visual fields in five non-sequential lung sections were captured, digitized and saved on a Macintosh computer (8100/100AV) using Adobe Photoshop software (version 3.0J; Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA). Inflammatory lesions were identified and the area of each selected region was measured using NIH image analysis software (version 1.61; Bethesda, MD). The selected areas of inflammatory lesions were measured and summated in every individual mouse. At the same time, the areas of total fields in the same lung sections were also quantified and summated. The severity of pathological changes in the lung was calculated by using the following formula: the relative area of lung lesions = sum of areas of lung lesions/total areas in five non-sequential sections of the right middle and lower lobes.

Extraction of RNA and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted from the left lungs of 7-, 11- and 26-week-old mice by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform method. For this purpose, 20–45 μg of RNA were obtained from each lung and resuspended in 30 μl of distilled water. Subsequently, RT was carried out by mixing 5 μg of the sample RNA solution (15 μl) with 2 μl of hexadeoxyribonucleotide mixture (Gibco BRL, Life Technologies, Tokyo, Japan). This solution was incubated for 2 min at 95°C and quickly cooled on ice. In the next step, 12 μl of a solution containing 6 μl of 5× reverse transcriptase buffer (250 mm Tris–HCl pH 8·3, 375 mm KCl, 15 mm MgCl2 (Gibco BRL)), 0·5 μl of RNase inhibitor (200 U/ml; Gibco BRL), 3 μl of 100 mm dithiothreitol, and 2·5 μl of 10 mm dNTP were added, and the tubes were incubated for 2 min at 37°C. We then added 1·0 μl Moloney murine leukaemia virus reverse transcriptase (200 000 U/ml; Gibco BRL) and incubated the sample for 60 min at 37°C. After adding 45 μl of 0·7 m NaOH and 40 mm EDTA, the tubes were incubated for 10 min at 65°C and quickly cooled on ice. The resultant cDNA was precipitated with 75% ethanol overnight at −70°C. The precipitates were washed once with 75% ethanol, dried, and resuspended in 50 μl of distilled water. The sample was stored at −20°C until use.

PCR was carried out in an automatic DNA thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, CT). For amplification of the desired cDNA, gene-specific primers (Table 1) were used. We added 1·0 μl of the sample cDNA solution to 49 μl of the reaction mixture, which contained 10 mm Tris–HCl pH 8·3, 50 mm KCl, 1·5 mm MgCl2, 10 μg/ml of gelatin, dNTP (each at a concentration of 200 mm), 1·0 mm sense and anti-sense primer, and 1·25 U of Ampli-Taq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer Cetus). The preparations in the microtubes were amplified by using a three-temperature PCR system usually consisting of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, primer annealing at 55°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 1·5 min for p40tax, hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase (HPRT), IL-1β, TNF-α and IFN-γ. PCR conditions of denaturing at 95°C for 1 min, annealing at 62°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 1 min 45 s were used for monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), RANTES and IP-10. PCR conditions were one cycle of denaturing at 95°C for 2 min, followed by annealing at 56°C for 30 s and extension at 72°C for 1 min. This cycle was followed by 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 56°C, and 1 min at 72°C for macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α). The cycle numbers were changed every two cycles from 26 to 32 for HPRT and RANTES, 28–34 for IP-10, 32–38 for MCP-1 and p40tax and 32–38 for MIP-1α. PCR products were electrophoresed on 2% agarose gel, stained with 0·5 μg/ml of ethidium bromide, and observed with a UV transilluminator.

Table 1.

Sequences of the oligonucleotide primers for polymerase chain reaction amplification of cytokines, p40tax, and chemokines

| mRNA | Primer sequence (5′→3′) | |

|---|---|---|

| HPRT | Sense | GTT GGA TAC AGG CCA AGA CTT TGT TG |

| Anti-sense | GAT TCA ACT TGC GCT CAT CTT AGG C | |

| p40tax | Sense | ATC CCG TGG AGA CTC CTC AA |

| Anti-sense | AAC ACG TAG ACT GGG TAT CC | |

| IL-1β | Sense | GCA ACT GTT CCT GAA CTCA |

| Anti-sense | CTC GGA GCC TGT AGT GCA G | |

| TNF-α | Sense | GGC AGG TCT ACT TTG GAG TCA TTG C |

| Anti-sense | ACA TTC GAG GCT CCA GTG AAT TCG G | |

| IFN-γ | Sense | AAC GCT ACA CAC TGC ATC T |

| Anti-sense | TGC TCA TTG TAA TGC TTG G | |

| MCP-1 | Sense | TCC ATG CAG GTC CCT GTC ATG CTT |

| Anti-sense | CTA GTT CAC TGT CAC ACT GGT C | |

| RANTES | Sense | TCT TCT CTG GGT TGG CAC ACA C |

| Anti-sense | CCT CAC CAT CAT CCT CAC TGC A | |

| IP-10 | Sense | CCC GGG AAT TCA TAC CAT GAA CCC AAG TGC TGC C |

| Anti-sense | GTC ACG ATG AAT TCC TTA AGG AGC CCT TTT AGA CCT | |

| MIP-1α | Sense | CAC CCT CTG TCA CCT GCT CAA CAT C |

| Anti-sense | GGT TCC TCG CTG CCT CCA AGA CTC T | |

| MIP-1β | Sense | GGA ATT CTG CAG TCC CAG CTC TGT GCA A |

| Anti-sense | GGA ATT CCA CAG TCA TAT CCA CAA TAG |

Primer sequences were obtained from previous reports by Gezzinelli et al. [33] for hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase (HPRT), by Kinoshita et al. [34] for p40tax, by Montgomery & Dallman [35] for IL-1β, by Murray et al. [36] for tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), by Pearlman et al. [37] for monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), RANTES, IP-10 and macrophage inflammatory protein-1 beta (MIP-1β), by Tessier et al. [38] for MIP-1α.

The obtained bands of amplified DNA were quantified using NIH image software and each value was plotted with the corresponding cycle number. Using this graph, we calculated the differentials in the PCR cycle number that provided the same intensity of amplified DNA between genes. The level of mRNA expression of p40tax and other cytokines was expressed as a reciprocal of the relative value to that of HPRT mRNA.

Oligonucleotide probes

Oligonucleotide probes were used with similar sequences, polarity (sense) or complementarity (anti-sense), to sequences in the HTLV-1 p40tax region: 5′ ACG CCC TAC TGG CCA CCT GTC CAG AGC ATC AGA TCA CCT G 3′ (7425–7464) [17] with additional 3 and 2 repeaters of adenine-thymine-thymine (ATT) at 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. The probes were haptenized by generating thymine-thymine dimers (T-T) by UV irradiation, as described by Koji et al. [18]. The optimal UV dose for these oligonucleotide probes was 10 000 J/m2 determined by dot blot hybridization using horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated mouse anti-T-T dimer IgG (Kyowa Hakko, Tokyo, Japan).

Detection of p40tax mRNA by in situ hybridization

For detection of p40tax mRNA in tissue sections by in situ hybridization, 3–5 μm thick sections were cut and deparaffinized. Sections were pretreated and in situ hybridized using the method described by Koji et al. [18]. Briefly, samples were rehydrated with PBS and incubated in 0·2 n HCl for 20 min at room temperature, then treated with 100 μg/ml of proteinase K (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Tokyo, Japan) for 15 min at 37°C. After washing with PBS, the specimens were re-fixed with 4% PFA/PBS for 5 min and treated twice with glycine solution (2 mg/ml). The specimens were then prehybridized with a solution containing 50% (v/v) deionized formamide, 4× SSC for 1 h at room temperature. For hybridization, 3–4 μg/ml T-T dimerized DNA probe in 10 mm Tris–HCl buffer pH 7·4, 0·6 m NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1× Denhardt’s solution, 250 μg/ml yeast tRNA, 125 μg/ml salmon sperm DNA, 10% dextran sulphate, and 40% deionized formamide were annealed at 41°C overnight in a humid chamber. After repeated washings, the hybridized probes were reacted with HRP-conjugated mouse anti-T-T dimer IgG in succession and sites of peroxidase were visualized by DAB in the presence of H2O2 and nickel and cobalt ions as chromogens.

The lungs of transgenic mice were tested with the anti-sense and sense HTLV-1 p40tax probes, the positive and negative probes, respectively. At the same time, those of littermate mice were also tested with anti-sense p40tax probe as negative tissue controls. In addition, MT-2 cells (obtained from Fujisaki Cell Centre, Hayashibara, Okayama, Japan) were used as an HTLV-1 mRNA-positive control, and Molt-3 (obtained from Fujisaki Cell Centre), HL-60, U937 and THP-1 (obtained from Cancer Cell Repository, Research Institute for Tuberculosis and Cancer, Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan) were used as a negative control.

Statistical analysis

Linear least-squares regression analysis was used to estimate the relationship between chemokine mRNA expression and the level of pathological changes in the lungs. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student’s t-test. P<0·05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Expression of p40tax mRNA and cellular inflammatory changes in lungs of transgenic mice

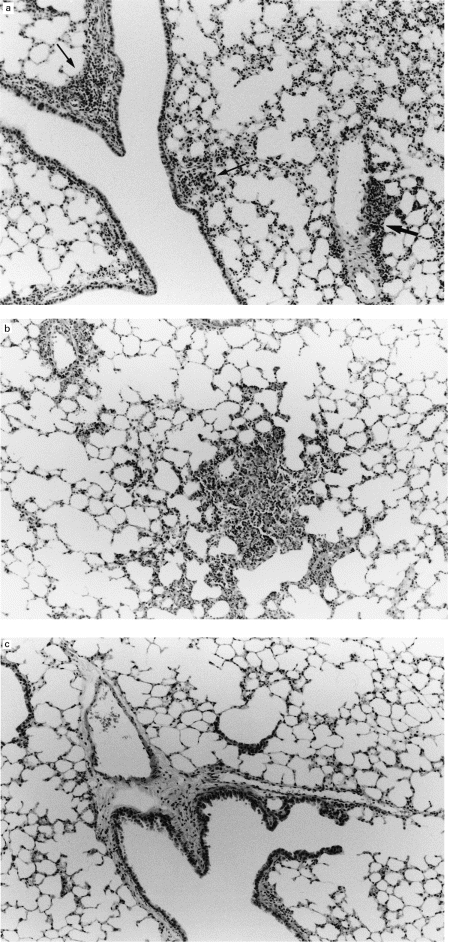

As shown in Fig. 1, inflammatory leucocytes consisting mainly of lymphocytes accumulated in peribronchial (arrows: Fig. 1a) and perivascular areas (bold arrow: Fig. 1a) and in alveolar septa (Fig. 1b) in the lungs of transgenic mice. In contrast, there were no marked changes in littermate mice (Fig. 1c). Compatible with this finding, pulmonary intraparenchymal leucocyte analysis showed a significant increase in the number of mononuclear leucocytes, such as lymphocytes and macrophages, but not neutrophils, in the lungs of transgenic mice, compared with those of littermate mice (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Representative examples of histopathological findings in the lungs of transgenic mice. Histopathological changes in the lungs of transgenic mice included accumulation of inflammatory cells, consisting mainly of lymphocytes, in peribronchiolar (arrows), perivascular area (bold arrow) (a) and alveolar septa (b) (26 weeks old). Note lack of similar changes in a littermate mouse (c). (H–E staining, mag. ×33.)

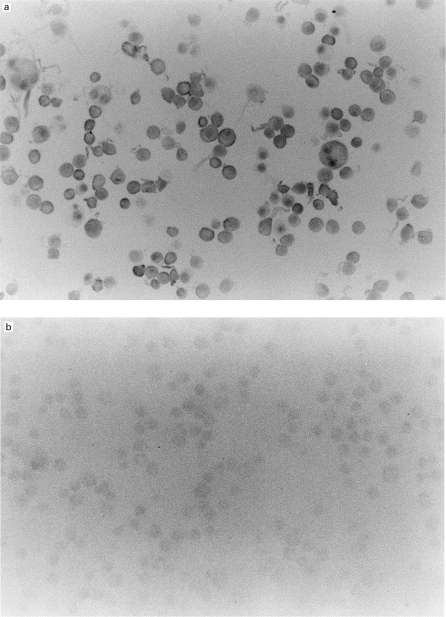

In our recent study [12], the mRNA level of p40tax in the lungs, evaluated semiquantitatively by RT-PCR, correlated with the severity of histopathological changes in transgenic mice. However, this observation did not provide evidence for a direct relationship between histopathological changes and distribution of p40tax. In the present study therefore we examined the distribution of p40tax in the lungs of transgenic mice using in situ hybridization and compared it with histopathological changes. For this purpose, we first established the specificity of anti-sense p40tax probe using a HTLV-1+ cell line, MT-2. When these cells were hybridized with the anti-sense p40tax probe, a signal was detected in all nuclei and cytoplasmic areas (Fig. 2a). No staining was found with the sense p40tax probe in these cells (Fig. 2b). In addition, several HTLV-1− cell lines, such as Molt-3, HL-60, U937 and THP-1, did not show any positive staining even when the anti-sense probe was used (data not shown). These results confirm that positive signals produced by this method were specific for HTLV-1 p40tax mRNA.

Fig. 2.

In situ expression of p40tax mRNA in MT-2 cells (a). In situ hybridization with an anti-sense p40tax probe showed a signal in all nuclei and cytoplasmic areas of MT-2 cells. (b) Specificity was confirmed by the lack of signals with the sense probe. (Mag. ×66.)

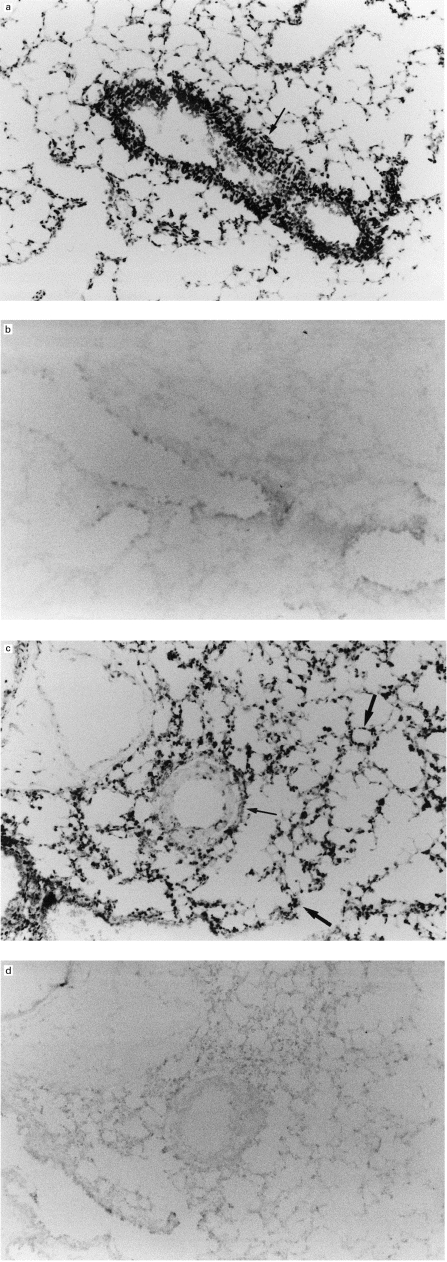

In the next step we examined the distribution of p40tax in the lung. As shown in Fig. 3a, marked expression of p40tax mRNA was observed around peribronchial areas (arrow) when the anti-sense probe was used, while no signal was detected with the sense probe in serial sections (Fig. 3b). In other sections, the expression of this gene was detected around perivascular areas (arrow: Fig. 3c) and alveolar septa (bold arrows: Fig. 3c), although the signals were weaker than those in Fig. 3a. No signal was detected in serial sections examined with the sense probe (Fig. 3d). These results indicate that the distribution of p40tax expression matched that of histopathological changes.

Fig. 3.

Expression of p40tax in lungs of transgenic mice. In situ hybridization of lung specimens from 26-week-old transgenic mice using an anti-sense p40tax probe. Note strong signals around peribronchiolar area (arrow) (a), and lack of signal in serial sections using the sense probe (b). Weaker signals of p40tax mRNA are present around perivascular (arrow) and alveolar septa (bold arrows), compared with those in (a) when the anti-sense probe is used (c), while no signal is present when the sense probe is used (d). (Mag. ×33.)

Production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in lungs of transgenic mice

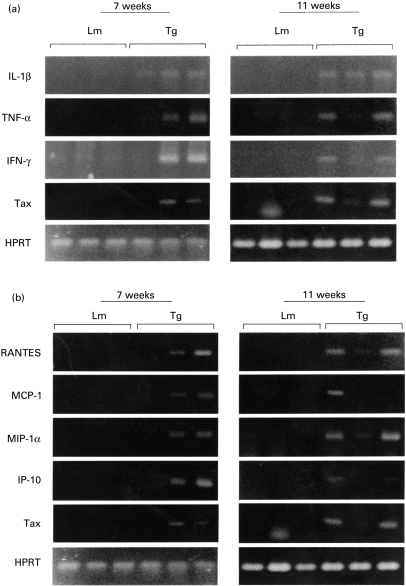

HTLV-1 p40tax is known to activate its own replication as well as a variety of cellular genes, including those of inflammatory cytokines [1] and chemokines [16]. In the next experiments, to determine the mechanisms responsible for accumulation of inflammatory cells, we examined the production of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF-α and IFN-γ and chemokines including RANTES, MCP-1, MIP-1α and IP-10 in the lungs of transgenic mice at mRNA level using the RT-PCR method. As shown in Fig. 4, the above inflammatory cytokines and chemokines were clearly expressed in transgenic mice, but not in control mice. The results of p40tax mRNA expression are shared with those shown in Fig. 2 of our parallel study [12]. Interestingly, the expression of these chemokines correlated with that of p40tax mRNA, i.e. the synthesis of chemokines was observed only in mice that showed p40tax expression. This finding suggested the involvement of p40tax in the synthesis of these chemokines. To test this conclusion, we compared the synthesis of these chemokines with the expression of p40tax mRNA among six transgenic mice using a semiquantitative analysis with RT-PCR, in which the levels of MCP-1, RANTES, MIP-1α, IP-10 and p40tax mRNA expression were calculated relative to that of HPRT. There was a significant correlation between p40tax mRNA and MCP-1 expression (r = 0·92, P = 0·008) but not with RANTES (r = 0·21, P = 0·135), MIP-1α (r = 0·60, P = 0·205) and IP-10 (r = 0·61, P = 0·195).

Fig. 4.

Expression of cytokine and chemokine mRNA in lungs of transgenic mice. Transgenic (Tg) and littermate mice (Lm) were killed at the ages of 7 and 11 weeks and total RNA was extracted from their lungs. Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction was carried out for p40tax and inflammatory cytokines (a), and chemokines (b). Hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase (HPRT) was used as an internal control.

Relationship between expression of chemokines and cellular inflammatory changes in lungs of transgenic mice

Chemokines are known to play a central role in infiltration of inflammatory leucocytes into the tissue. As indicated above, augmented synthesis of RANTES, MCP-1, MIP-1α and IP-10 was noted in the lungs of transgenic mice. Accordingly, we then examined the relationship between the expression of these chemokines and histopathological scores of lung lesions among six transgenic mice. The severity of histopathological changes was determined by calculating the areas showing accumulation of inflammatory leucocytes relative to the total areas of lung sections, as described in Materials and Methods. There was a significant relationship between cellular inflammatory changes and gene expression of all chemokines (MCP-1: r = 0·97, P = 0·001; RANTES: r = 0·86, P = 0·025; IP-10: r = 0·84, P = 0·037) with the exception of MIP-1α (r = 0·15, P = 0·76).

DISCUSSION

We have recently demonstrated the presence of inflammatory changes in the lungs of transgenic mice bearing the pX region of HTLV-1 [12]. These changes were characterized by lymphocytic accumulation around peribronchiolar and perivascular areas and in alveolar septa. In the same study, we used RT-PCR and demonstrated a positive correlation between the expression of p40tax mRNA and histopathological scores of lung lesions [12]. These findings suggested that p40tax might be directly involved in the pathogenesis of HTLV-1-associated pulmonary inflammatory diseases.

We extended the above findings in the present study by examining the distribution of p40tax mRNA expression in the lungs of transgenic mice and correlation of this with accumulation of inflammatory cells in the lung. In situ hybridization analysis showed a strong expression of p40tax mRNA around peribronchial areas and to a lesser extent around perivascular areas and alveolar septa. Interestingly, the distribution of these cells was similar to that of p40tax mRNA expression. Combined with the results of our recent study, the present findings indicate that expression of p40tax is directly involved in the pathogenesis of HTLV-1-associated pulmonary diseases. Our results are similar to those of several other groups demonstrating a correlation between p40tax mRNA expression and pathological changes in other tissues. For example, in specimens obtained from HAM/TSP patients, p40tax mRNA was detected in infiltrating CD4+ T cells [19] and neuroglial cells, including astrocytes [20], which were distributed around blood vessels in inflammatory and degenerative areas. These investigators speculated that the expression of p40tax mRNA might play an important role in provoking immune responses and lymphocyte accumulation, including HTLV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes, during the development of HAM/TSP [19,21,22]. Other investigators demonstrated the expression of p40tax mRNA as detected by RT-PCR in fresh synovial tissues and cultured synovial cells obtained from patients with HTLV-1-associated arthropathy, and that such expression induced over-expression of HLA class II molecules, resulting in the enhancement of immune response to these cells [23,24]. Considered collectively, these findings suggested that the expression of p40tax mRNA might directly or indirectly contribute to the pathogenesis of HTLV-1-associated diseases through the induction of immune responses.

Recently, many studies have demonstrated that inflammatory cytokines enhance the accumulation of inflammatory leucocytes. Furthermore, these cytokines, including IL-1β, TNF-α and IFN-γ, also augment the expression of adhesion molecules, such as intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and selectins, on vascular endothelial cells and leucocytes [25, 26], which play an important role in trafficking of leucocytes from the circulation into the site of inflammation [13]. Several studies using mice genetically depleted of adhesion molecules have confirmed these observations [27, 28]. Because the above inflammatory cytokines were clearly synthesized in the lungs of transgenic mice, adhesion molecules might also be involved in the accumulation of inflammatory leucocytes into lung lesions. In support of this argument, results of preliminary experiments from our laboratory have recently demonstrated over-expression of LFA-1 and ICAM-1 on the surface of lymphocytes obtained from lungs of transgenic mice. On the other hand, transmigration of inflammatory cells into the inflammatory sites is strictly regulated by a variety of chemokines, which are classified into two structurally related subfamilies based on the arrangement of the first two of four conserved cysteines, i.e. adjacent to one another or separated by one amino acid (C-C or C-X-C chemokines, respectively) [14, 15,29]. The C-X-C chemokines such as IL-8, MIP-2 and KC act predominantly on neutrophils, while the C-C chemokines including MCP-1, RANTES, MIP-1α and MIP-1β attract mainly monocytes, lymphocytes, eosinophils and basophils [14,15,29]. IP-10 selectively stimulates the migration of monocytes and lymphocytes into inflammatory sites, although it belongs to the C-X-C subfamily [30]. In the present study we examined the expression of mononuclear leucocyte-trafficking chemokines such as MCP-1, RANTES, MIP-1α and IP-10, because lymphocytes were the major infiltrating leucocytes in lung lesions of transgenic mice. The expression of these chemokines was clearly present at mRNA level in the lungs of transgenic mice but not in control littermate mice, suggesting the likely involvement of these chemokines in the development of cellular inflammatory lesions in the lungs. Furthermore, these cellular inflammatory responses might be potentiated through the enhanced production of chemokines by inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, TNF-α and IFN-γ, as recently demonstrated by several investigators [14, 15, 29, 31].

The protein product of HTLV-1 pX gene, p40tax, is known to act as a transactivation factor on the long-terminal repeat of HTLV-I itself as well as on promoters of many cellular genes including cytokines, cellular oncogenes and cell surface molecules [1]. Iwakura et al. [32] indicated that genes for several inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, TGF-β1, IFN-γ and IL-2, were activated in the inflammatory joints of p40tax transgenic mice. Our present results confirm these observations in lungs of the same animal. In addition, an interesting finding has recently been reported by Baba et al. [16], which demonstrated that both HTLV-I-infected and p40tax-transfected cells spontaneously produced large amounts of chemokines, including IL-8, IP-10, MIP-1α and MIP-1β, although it remains to be elucidated whether such expression was mediated by direct action of viral products on their own promoter. In addition, we have demonstrated that several T cell lines obtained from HTLV-1-infected patients spontaneously expressed p40tax as well as mRNAs of several chemokines using RT-PCR (unpublished data). In the present study, both inflammatory cytokines and chemokines were detected at mRNA level and the expression of some chemokines including MCP-1, RANTES, MIP-1α and IP-10 seemed to correlate with that of p40tax mRNA in the lungs of transgenic mice. Furthermore, the relationships between gene expression of most of these chemokines and severity of histopathological changes in lungs were significant. These results suggested that mononuclear cell-trafficking chemokines produced by p40tax-expressing cells might cause infiltration of lymphocytes in the lungs of transgenic mice. It should be noted here that there is another possibility that the positive relationship between p40tax and chemokine expression may just be a reflection of the increased number of leucocytes expressing them at the inflammatory lesions. However, this possibility is less likely, because the expression of both p40tax and chemokines was detected in lungs before the appearance of the inflammatory lesions in 7-week-old transgenic mice [12].

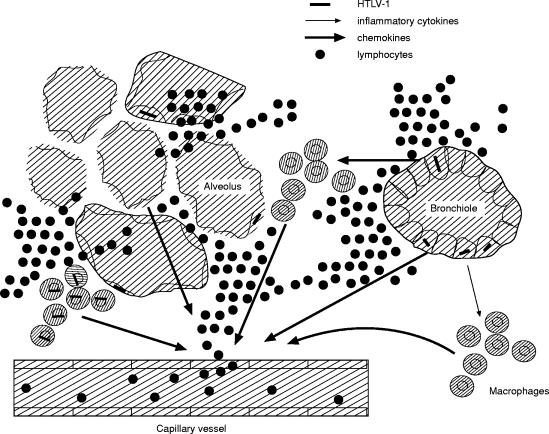

Although direct evidence has not so far been obtained, the findings of the present study allow the construction of a hypothesis in which chemokines, produced directly by HTLV-1-infected cells [16] or indirectly by uninfected cells upon stimulation by inflammatory cytokines synthesized from infected cells [14, 15, 29, 31], are involved in the pathogenesis of HTLV-1-associated pulmonary diseases, as shown schematically in Fig. 5. To confirm this hypothesis, further studies are necessary to examine the distribution of chemokine mRNA expression using in situ hybridization and the effects of neutralizing antibodies against these chemokines on the development of cellular inflammatory changes in the lungs.

Fig. 5.

Schematic diagram of pathogenic mechanisms of HTLV-1-associated pulmonary inflammation. Chemokines, produced directly by HTLV-I-infected cells or indirectly by uninfected cells upon stimulation by inflammatory cytokines synthesized by infected cells, might be involved in the pathogenesis of HTLV-1-associated lung disorder.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yoshida M, Suzuki T, Fujiwara J, et al. HTLV-1 oncoprotein tax and cellular transcription factors. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;193:79–89. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78929-8_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sugamura K, Hinuma Y. The retoroviridae. New York: Plenum Press; 1993. Human retroviruses: HTLV-I and HTLV-II; pp. 399–435. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osame M, Usuku K, Izumo S, et al. HTLV-1-associated myelopathy, a new clinical entity. Lancet. 1986;i:1031–2. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)91298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gessain A, Barin F, Vernant JC, et al. Antibodies to human T-lymphotropic virus type I in patients with tropical spastic paraparesis. Lancet. 1985;ii:407–10. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)92734-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mochizuki M, Watanabe T, Yamaguchi K, et al. HTLV-1 uveitis, a distinct entity caused by HTLV-1. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1992;83:236–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1992.tb00092.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nishioka K, Maruyama I, Sato K, et al. Chronic inflammatory arthropathy associated with HTLV-1. Lancet. 1989;i:441. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sugimoto M, Nakashima H, Matsumoto M, et al. Pulmonary involvement in patients with HTLV-1-associated myelopathy: increased soluble IL-2 receptors in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;139:1329–35. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/139.6.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maruyama I, Tihara J, Sakashita I, et al. HTLV-1 associated bronchopneumonopathy, a new clinical entity? Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;137:46. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho I, Sugimoto M, Mita S, et al. In vivo proviral burden and viral RNA expression in T cell subsets of patients with human T lymphotropic virus type-1-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;53:412–8. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1995.53.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higashiyama Y, Katamine S, Kohno S, et al. Expression of human T lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) tax/rex gene in fresh bronchoalveolar lavage cells of HTLV-1-infected individuals. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994;96:193–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06541.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwakura Y, Tosu M, Yoshida E, et al. Induction of inflammatory arthropathy resembling rheumatoid arthritis in mice transgenic for HTLV-1. Science. 1991;253:1026–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1887217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawakami K, Miyazato A, Iwakura Y, et al. Induction of lymphocytic inflammatory changes in the lung interstitium by human T cell leukemia virus type 1. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:995–1000. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.3.9808125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Springer TA. Traffic signals for lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte emigration: the multiple paradigm. Cell. 1994;76:301–14. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baggiolini M, Dewald B, MoSeries B. Interleukin-8 and related chemotactic cytokines-CXC and CC chemokines. Adv Immunol. 1994;55:97–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oppenheim JJ, Zachariae COS, Mukaida N, et al. Properties of the novel proinflammatory supergene ‘intercrine “ cytokine family. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:617–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.003153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baba M, Imai T, Yoshida T, et al. Constitutive expression of various chemokine genes in human T-cell lines infected with human T-cell leukemia virus type 1: role of the viral transactivator tax. Int J Cancer. 1996;66:124–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960328)66:1<124::AID-IJC21>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seiki M, Hattori S, Hirayama Y, et al. Human adult T-cell leukemia virus: complete nucleotide sequence of the provirus genome integrated in leukemia cell DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:3618–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.12.3618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koji T, Nakane PK. Localization in situ of specific mRNA using thymine-thymine dimerized DNA probes. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1990;40:793–807. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1990.tb02492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moritoyo T, Reinhart TA, Moritoyo H, et al. Human T-lymphotropic virus type I-associated myelopathy and tax gene expression in CD4+ T lymphocytes. Ann Neurol. 1996;40:84–90. doi: 10.1002/ana.410400114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lehky TJ, Fox CH, Koenig S, et al. Detection of human T-lymphotropic virus type I (HTLV-I) tax RNA in the central nervous system of HTLV-I-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis patients by in situ hybridization. Ann Neurol. 1995;37:167–75. doi: 10.1002/ana.410370206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Umehara F, Izumo S, Nakagawa M, et al. Immunocytochemical analysis of the cellular infiltrate in the spinal cord lesions in HTLV-1-associated myelopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1993;52:424–30. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199307000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Umehara F, Nakamura A, Izumo S, et al. Apoptosis of T lymphocytes in the spinal cord lesions in HTLV-1-associated myelopathy: a possible mechanism to control viral infection in the central nervous system. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1994;53:617–24. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199411000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kitajima I, Yamamoto K, Sato K, et al. Detection of human T cell lymphotropic virus type I proviral DNA and its gene expression in synovial cells in chronic inflammatory arthropathy. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:1315–22. doi: 10.1172/JCI115436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakajima T, Aono H, Hasunuma T, et al. Overgrowth of human synovial cells driven by the human T cell leukemia virus type I tax gene. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:186–93. doi: 10.1172/JCI116548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tessier P, Audette M, Cattaruzzi P, et al. Up-regulation by tumor necrosis factor alpha of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 expression and function in synovial fibroblasts and its inhibition by glucocorticoids. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36:1528–39. doi: 10.1002/art.1780361107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bevilacqua MP. Endothelial-leukocyte adhesion molecules. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11:767–804. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.004003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sligh JE, Ballantyne CM, Rich SS, et al. Inflammatory and immune responses are impaired in mice deficient in intracellular adhesion molecule 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8529–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mayadas TN, Johnson RC, Rayburn H, et al. Leukocyte rolling and extravasation are severely compromised in, p selectin-deficient mice. Cell. 1993;74:541–54. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80055-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schall TJ, Bacon KB. Chemokines, leukocyte trafficking, and inflammation. Curr Opin Immunol. 1994;6:865–73. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taub DD, Lloyd AR, Conlon K, et al. Recombinant human interferon-inducible protein 10 is a chemoattractant for human monocytes and T lymphocytes and promotes T cell adhesion to endothelial cells. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1809–15. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.6.1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rollins BJ, Yoshimura T, Leonard EJ, et al. Cytokine activated human endothelial cells synthesize and secrete a monocyte chemoattractant, MCP-1/JE. Am J Pathol. 1990;136:1229–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iwakura Y, Saijo S, Kioka Y, et al. Autoimmune induction by human T cell leukemia virus type 1 in transgenic mice that develop chronic inflammatory arthropathy resembling rheumatoid arthritis in human. J Immunol. 1995;155:1588–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gazzinelli R, Eltoum I, Wynn TA, et al. Acute cerebral toxoplasmosis is induced by in vivo neutralization of TNF-α and correlates with the down-regulated expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and other markers of macrophage activation. J Immunol. 1993;151:3672–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kinoshita T, Shimoyama M, Tobinai K, et al. Detection of mRNA for the tax1/rex1 gene of human T-cell leukemia virus type I in fresh peripheral blood mononuclear cells of adult T-cell leukemia patients and viral carriers by using the polymerase chain reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5620–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.14.5620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Montgomery R, Dallman MJ. Analysis of cytokine gene expression during fetal thymic ontogeny using the polymerase chain reaction. J Immunol. 1991;147:554–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murray LJ, Lee R, Martens C. In vivo cytokine gene expression in T cell subsets of the autoimmune MRL/Mp-lpr/lpr mouse. Eur J Immunol. 1990;20:163–70. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830200124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pearlman E, Lass JH, Gardensein DS, et al. IL-12 exacerbates Helminth-mediated corneal pathology by augmenting inflammatory cell recruitment and chemokine expression. J Immunol. 1997;158:827–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tessier PA, Naccache PH, Clark-Lewis I, et al. Chemokine networks in vivo. Involvement of C-X-C and C-C chemokines in neutrophil extravasation in vivo in response to TNF-α. J Immunol. 1997;159:3595–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]