Abstract

HIV-1 gene expression is regulated by the promoter/enhancer located within the U3 region of the proviral 5′ LTR that contains multiple potential cis-acting regulatory sites. Here we describe that the inhibitor of the cellular ribonucleoside reductase, hydroxyurea (HU), inhibited phorbol myristate acetate- or tumour necrosis factor-alpha-induced HIV-1-LTR transactivation in both lymphoid and non-lymphoid cells in a dose-dependent manner within the first 6 h of treatment, with a 50% inhibitory concentration of 0·5 mm. This inhibition was found to be specific for the HIV-1-LTR since transactivation of either an AP-1-dependent promoter or the CD69 gene promoter was not affected by the presence of HU. Moreover, gel-shift assays in 5.1 cells showed that HU prevented the binding of the NF-κB to the κB sites located in the HIV-1-LTR region, but it did not affect the binding of both the AP-1 and the Sp-1 transcription factors. By Western blots and cell cycle analyses we detected that HU induced a rapid dephosphorylation of the pRB, the product of the retinoblastoma tumour suppressor gene, and the cell cycle arrest was evident after 24 h of treatment. Thus, HU inhibits HIV-1 promoter activity by a novel pathway that implies an inhibition of the NF-κB binding to the LTR promoter. The present study suggests that HU may be useful as a potential therapeutic approach for inhibition of HIV-1 replication through different pathways.

Keywords: hydroxyurea, NF-κB, HIV-1, LTR

INTRODUCTION

HIV-1 infects T cells and monocytes in both a latent and a productive manner [1–3]. Replication of HIV-1 in cell lines and in cells from infected patients often requires agonists to activate the cell and its latent virus [4]. Cytokines such as granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), IL-3 and IL-6 up-regulate virus expression, whereas tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) is a particularly potent activator [5–8].

The regulation of HIV-1 replication is mediated by both viral proteins and cellular factors that play a critical role in the transcription of the HIV-1-LTR promoter [9,10]. Among those cellular factors, the nuclear factor NF-κB is of special interest in transcriptional regulation of HIV-1 [11]. Two highly conserved consecutive copies of κB elements at nucleotides −104 to −81 are critical for HIV-1 replication in T cells [12,13]. NF-κB is made of hetero- or homodimeric combinations of several proteins that belong to the same family (Rel family). The five known mammalian Rel/NF-κB proteins, NF-κB1 (p50), NF-κB2 (p52), RelA (p65), RelB and c-Rel, share a highly conserved Rel homology domain that contains sequences required for DNA binding, protein dimerization, and nuclear localization [14]. The most common species are p50 subunit homodimers or heterodimers consisting of a p50 subunit and either a p65 (RelA) subunit or the product of the c-rel oncogen (c-Rel). NF-κB is rendered inactive in the cytoplasm by inhibitory proteins called IκB in unstimulated cells. In response to extracellular stimuli, the IκB proteins are phosphorylated on specific serine residues and tagged for ubiquinitation and degradation by the proteasome, leading to the nuclear localization and activation of NF-κB [15–17]. A kinase complex consisting of NIK and IKK-α/β is involved in signal-induced phosphorylation of IκB proteins [18–20].

Efforts to find an effective anti-HIV-1 chemotherapy have been focused on the development of chemicals that inhibit viral proteins, which are essential for HIV replication. The most important limitation of this therapeutic approach is the rapid generation of mutated quasispecies of HIV-1 resistant to those inhibitors. It has been suggested that a combination of antiviral chemotherapy with some inhibitors of cellular proteins may greatly improve the anti-HIV-1 treatment [21–24]. Among these proteins, the cellular enzyme ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase may be an important target, since this enzyme can be inhibited by compounds of the hydroxamate family such as hydroxyurea (HU) [25].

HU is a free radical quencher that inhibits the cellular enzyme ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase and, in so doing, reduces the levels of deoxyribonucleotides [26]. HU has been used over the last 30 years for the treatment of human diseases such as chronic myelogenous leukaemia, myeloproliferative syndromes and more recently sickle cell anaemia [27–31]. Moreover, HU inhibits HIV-1 DNA synthesis in activated peripheral blood lymphocytes by decreasing the amount of intracellular deoxynucleotides. Combination of HU with the nucleoside analogue didanosine (2′,3′-dideoxynosine, or ddI) generated a synergistic inhibitory effect without increasing toxicity [26,32–34].

In the present study we show that HU inhibits the HIV-1-LTR transactivation in response to either TNF-α or phorbol myristate acetate (PMA). This inhibition was found to be specific for the LTR, since transactivation of either the CD69 promoter or an AP-1-dependent promoter was not affected by the presence of HU. Moreover, we show that HU dephosphorylates the product of the retinoblastoma gene (pRB) and inhibits the binding activity of NF-κB to the κB sites located in the HIV-1-LTR. These data suggest that HU may inhibit HIV-1 replication by a novel pathway independent of the inhibition of the ribonucleoside reductase.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and reagents

The J.Jhan T cell line (a Jurkat-derived clone) and the 5.1 clone (obtained from Dr N. Isräel, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France) were maintained in exponential growth in RPMI 1640 medium (Bio-Whittaker, VerViers, Belgium). The human embryonic kidney-derived 293T cells and the cervix cancer HeLa cells (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Bio-Whittaker). The culture media were supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), 2 mm l-glutamine and the antibiotics penicillin and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) (Gibco, Paisley, UK). The 5.1 cell line is a J.Jhan-derived clone stably transfected with a plasmid containing the luciferase gene driven by the HIV-LTR promoter and was maintained in the presence of G418 (100 μg/ml). γ32P-ATP (3000 Ci/mmol) was purchased from ICN (Costa Mesa, CA). All other reagents were from Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO).

Transient transfections and luciferase activity

293T cells (105/ml) were transiently transfected in 24-well plates by using lipofectamine as described by the manufacturer (Gibco BRL). The cells were transfected with 1 μg/ml of the following plasmids: (i) the HIV-LTR promoter (LAV1 Bru strain) followed by the luciferase gene [35]; (ii) the AP-1-Luc reported plasmid (constructed by inserting three copies of a SV40 AP-1 binding site into the Xho site of pGL-2 promoter vector (Promega Co., Madison, WI); and (iii) the AIM-170-Luc plasmid that contains the luciferase gene driven by 170 bp of the proximal CD69 promoter [36]. HeLa cells (105/ml) were transfected as above with the HIV-1-LTR-Luc plasmid (1 μg/ml), and Jhan cells (2 × 107) were transfected by electroporation (BioRad Gene Pulser apparatus) at 150 V/960 μ F with 20 μg of the HIV-1-LTR-Luc plasmid. Twenty-four hours after transfection the cells were stimulated as indicated and then lysed in 25 mm Tris-phosphate pH 7·8, 8 mm MgCl2, 1 mm DTT, 1% Triton X-100, and 15% glycerol. Luciferase activity was measured in a luminometer (Lumat; Berthold, Wildbad, Germany) following the instructions of the luciferase assay kit (Promega). The background obtained with the lysis buffer was subtracted in each experimental value, and the luciferase activity measured as above described. All the experiments were repeated at least three times.

Western blots

Total cellular proteins were extracted in lysis buffer (20 mm Tris–HCl pH 7·4; 10 mm EDTA; 100 mm NaCl; 1% Triton X-100; 1 mm each PMSF, sodium fluoride, β-glycerophosphate, sodium vanadate and EGTA; 5 μg/ml each Na-p-tosyl-l-lysine choromethyl ketone (TLCK), leupeptin and pepstatin; and 5 mm sodium pyrophosphate). Thirty micrograms of proteins were boiled in Laemmli buffer and electrophoresed in 7% SDS/polyacrylamide gels. Separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and immunodetection of pRB protein was carried out with the anti-pRB MoAb 1F8 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Proteins detected by the primary antibody were visualized with horseradish peroxidase (HPRO)-labelled secondary antibody and the use of an enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham, Aylesbury, UK).

Isolation of nuclear extracts and electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA)

5.1 cells were cultured at 2 × 106/ml and stimulated with the agonists in complete medium as indicated. Cells were then washed twice with cold PBS and proteins from nuclear extracts isolated as previously described [37]. Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method (BioRad, Richmond, CA). For the EMSA assay we used either a double-stranded oligonucleotide that contains HIV-1-LTR sequences from −107 to −77 bp and includes two NF-κB-binding sites (5′-CAAGGGACTTTCCGCTGGGGACTTTCCAGGG-3′) (LTR-κB), or two commercial oligonucleotides containing the AP-1 site or the Sp1 binding site (Promega). The binding reaction mixture contained 3 μg of nuclear extract, 0·5 μg poly(dI-dC) (1·5 μg for the NF-κB binding) (Pharmacia Fine Chemical, Piscataway, NJ), 20 mm HEPES pH 7, 70 mm NaCl, 2 mm DTT, 0·01% NP-40, 100 μg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA), 4% Ficoll, and 100 000 ct/min of end-labelled DNA fragments in a total volume of 20 μl. When indicated, 0·5 μl of rabbit anti-p50, anti-p65 (RelA) or preimmune serum (PRE) was added to the standard reaction prior to the addition of the radiolabelled probe. For cold competition, a 100-fold excess of the double-stranded oligonucleotide competitor (LTR-κB, Ig-κB (Promega), and LTR-Ets (LTR sequences from −180 to −138)) was added to the binding reaction. After 30 min incubation at 4°C, the mixture was electrophoresed through a native 6% polyacrylamide gel containing 89 mm Tris-borate, 89 mm boric acid and 1 mm EDTA. Gels were pre-electrophoresed for 30 min at 225 V and then for 2 h after loading the samples. These gels were dried and exposed to XAR film at −70°C.

Cytofluorometric analysis of cell surface antigen and cell cycle

5.1 cells were treated for 16 h with either PMA (20 ng/ml) or TNF-α (50 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of HU (2 mm), and surface expression of the CD69 antigen was analysed by flow cytometry using MoAb TP1/55 [38]. Cells were incubated at 4°C with 100 μl of hybridoma culture supernatant, followed by washing and labelling with a FITC-tagged goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Biosource, Camarillo, CA). Cell surface fluorescence was measured on an EPICS XL Analyser (Coulter, Hialeah, FL). To study the cell cycle, 5.1-treated cells were fixed in ethanol (70%, for 24 h at 4°C), followed by RNA digestion (RNase-A, 50 U/ml) and propidium iodide (PI; 20 μg/ml) staining, and analysed by cytofluorometry as previously described [39].

RESULTS

HU inhibits LTR-HIV-1 transactivation

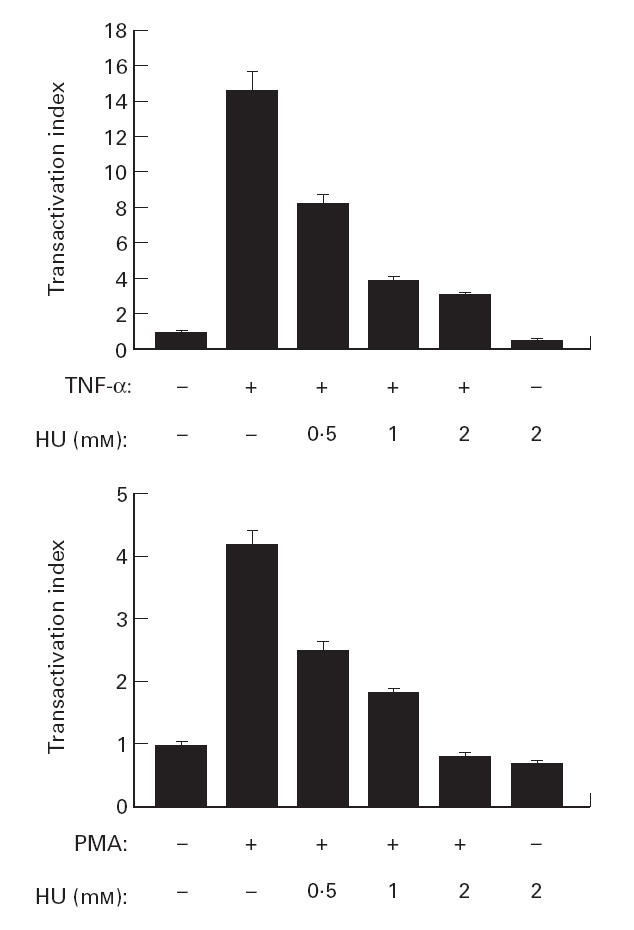

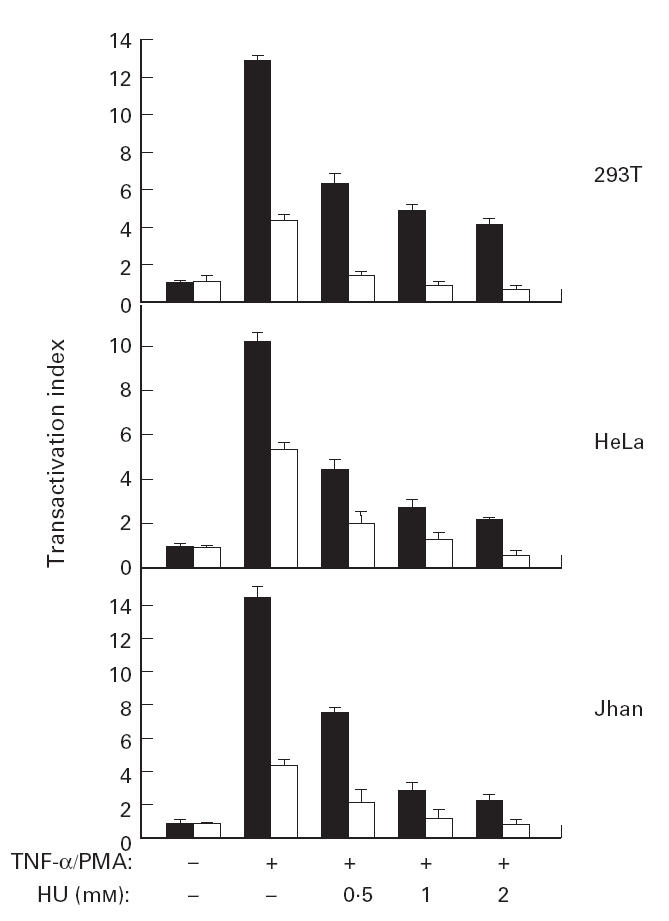

It has been suggested that HU inhibits HIV-1 DNA synthesis in activated peripheral blood lymphocytes by decreasing the amount of intracellular deoxynucleotides [26]. To evaluate the effects of HU in the transactivation of the LTR-HIV-1 promoter, we used the 5.1 clone, a Jurkat-derived cell stably transfected with a plasmid containing the luciferase gene driven by the LTR-HIV-1 promoter (LAV1 Bru strain) [35]. We preincubated the cell line with the increasing doses of HU, and 30 min later the cells were stimulated with TNF-α (50 ng/ml) or PMA (20 ng/ml) for 6 h. Then the cells were lysed and the luciferase activity was measured and expressed as the transactivation index. It is shown in Fig. 1 that TNF-α induced a strong LTR-HIV-1 transactivation in 5.1 cells (up to 15-fold induction over the basal levels). PMA also transactivated HIV-LTR but to a lesser extent (about 4·5-fold induction). Nevertheless, in both cases HU was able to inhibit in a dose-dependent manner (ranging between 0·5 and 2 mm) the transactivation of the HIV-LTR. Moreover, HU alone also had a modest inhibitory effect on the basal transcriptional activity of the HIV-LTR promoter. To study if the inhibition of HIV-1-LTR transcription by HU was cell type-independent, we performed transient transfections in different cell lines (HeLa, 293T and J.Jhan) with the HIV-LTR-Luc plasmid. After 24 h the cells were preincubated with increasing doses of HU and then stimulated with either TNF-α (20 ng/ml) or PMA (50 ng/ml) for 6 h. The results showed that HU inhibited both the TNF-α- and PMA-induced LTR transactivation in the three cell lines tested. Similar to what was found for 5.1 cells, this inhibition was also dose-dependent with about 50% of reduction with 0·5 mm of HU (Fig. 2). Altogether, these results demonstrated the ability of HU to inhibit HIV-LTR gene transcription independently of the stimuli and of the cell line.

Fig. 1.

Hydroxyurea (HU) inhibits HIV-1-LTR transactivation in 5.1 cells. The clone 5.1 was preincubated with the indicated concentration of HU, and then stimulated with tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α; 50 ng/ml) or phorbol myristate acetate (PMA; 20 ng/ml) for 6 h. The luciferase activity was measured and expressed as the transactivation index. Values are means ±s.d. of six independent experiments.

Fig. 2.

Hydroxyurea (HU) inhibits HIV-1-LTR transactivation in different cell lines. The cell lines HeLa, 293T and J.Jhan were transfected with the HIV-LTR-Luc plasmid. After 24 h, the cells were preincubated with increasing doses of HU and then stimulated with tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α;▪, 50 ng/ml) or phorbol myristate acetate (PMA; □, 20 ng/ml) for 6 h. The TNF-α- and PMA-induced LTR transactivation was expressed as the transactivation index. Values are means ±s.d. of three independent experiments.

HU does not affect CD69 gene transcription and expression in stimulated Jurkat cells

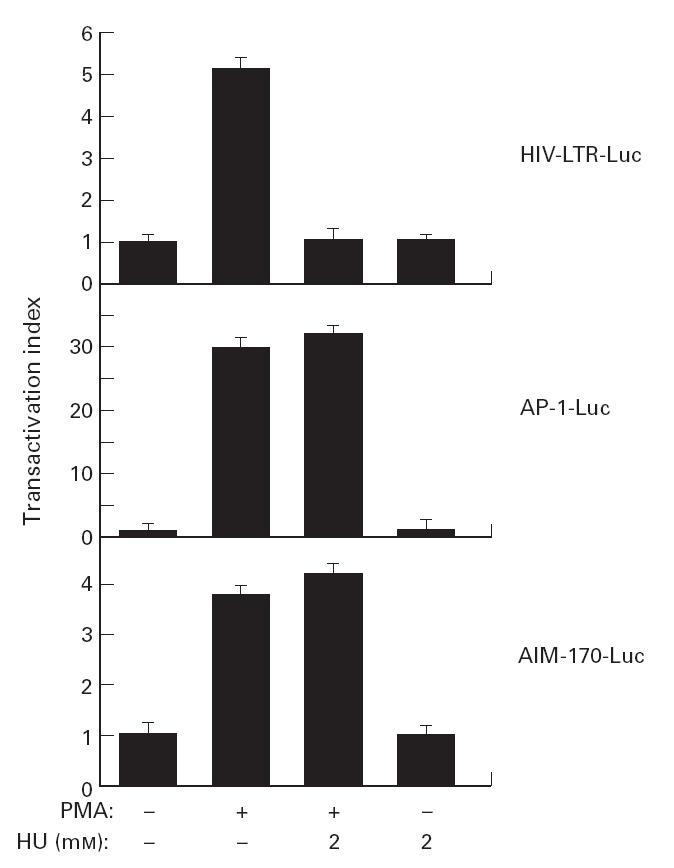

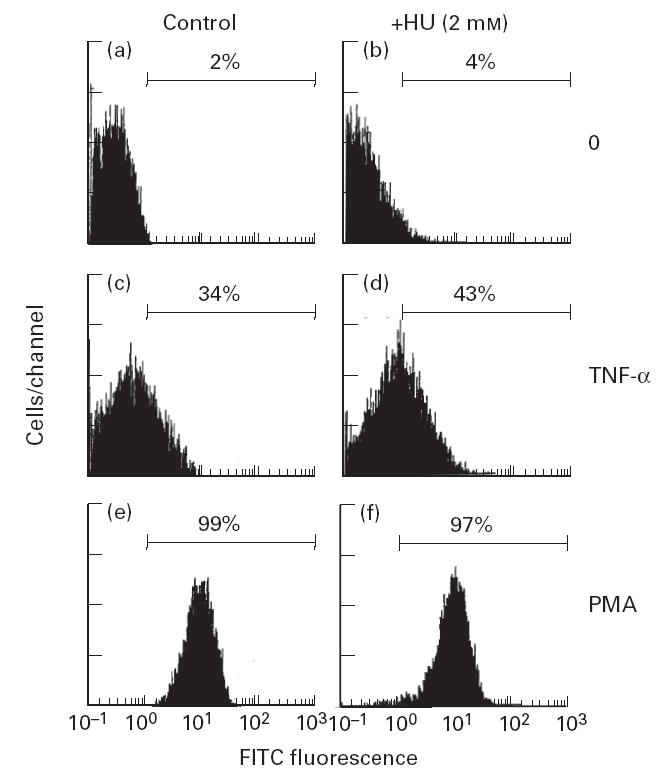

To study the specific inhibition of LTR-HIV-1 transactivation by HU, we transfected the J.Jhan cell line with the following plasmids: (i) the HIV-LTR-Luc; (ii) a plasmid containing three AP-1 sites followed by the luciferase gene; and (iii) the AIM-170-Luc plasmid, that includes the luciferase gene driven by a fragment of 170 bp of the AIM promoter [36]. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were incubated for 30 min with 2 mm of HU, and then stimulated with PMA (50 ng/ml) for 6 h. Then the cells were lysed and the luciferase activity was measured and expressed as the transactivation index. In Fig. 3 it is shown that again HU selectively inhibited LTR-HIV-1-dependent gene transcription, but did not affect either the AP-1-dependent transcription or the transcriptional activity of the AIM promoter. Moreover, in 5.1 cells stimulated for 18 h with either TNF-α (20 ng/ml) or PMA (50 ng/ml) the cell surface expression of the CD69/AIM antigen was not inhibited by the presence of HU (2 mm), but rather stimulated in the case of TNF-α(Fig. 4). This stimulation was highly reproducible but statistically not significant.

Fig. 3.

Effects of hydroxyurea (HU) in AP-1 and CD69 gene promoter in phorbol myristate acetate (PMA)-stimulated Jhan cells. Jhan cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids, and 24 h later preincubated with HU (2 mm) and stimulated with PMA (50 ng/ml) for 6 h. The luciferase activity was measured and expressed as the transactivation index. Each value represents the average of three independent assays.

Fig. 4.

Cell surface expression of the CD69/AIM antigen was not affected by hydroxyurea (HU). The 5.1 clone was stimulated for 18 h with either tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α; 20 ng/ml) or phorbol myristate acetate (PMA; 50 ng/ml), in the presence or absence of HU (2 mm) and the cell surface expression of CD69 measured by flow cytometry. The results shown are representative of four separate experiments.

HU induces dephosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein and cell cycle arrests in 5.1 cells

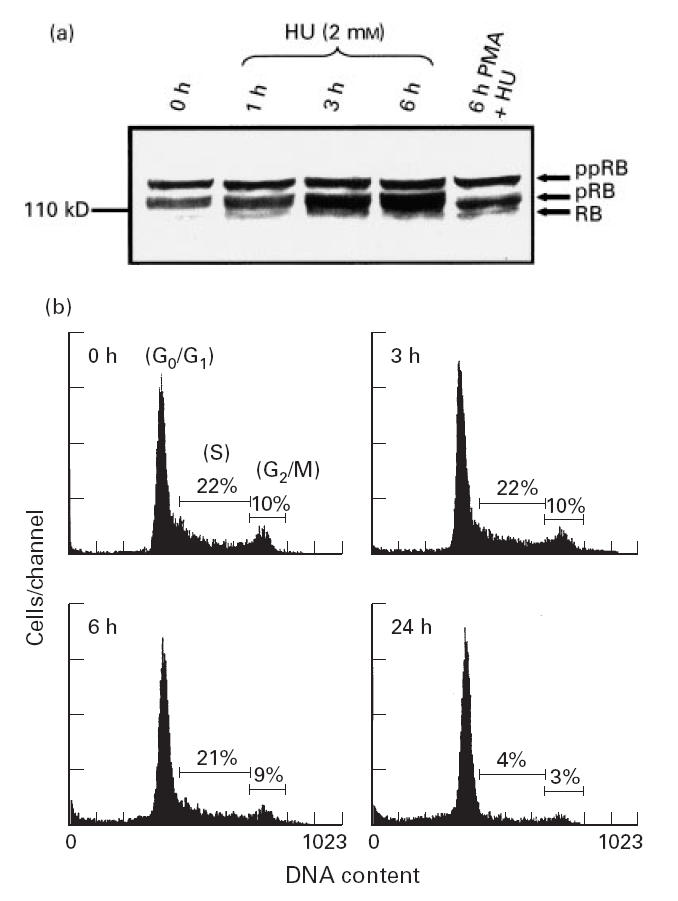

It has been demonstrated that the retinoblastoma gene product (pRB) controls the cell cycle progression at the G1/S boundary by inactivating the E2F transcription factor. In the phase G0 and in the proceeding hours of G1, pRB is found in an underphosphorylated form. In the last several hours of G1 and phase S, pRB is hyperphosphorylated, and pRB maintains this configuration until phase M, where upon emergence it loses its phosphate groups [40]. Since one of the characteristics of HU is to induce cell cycle arrest in phase S [41], we studied the effect of HU in the phosphorylation state of pRB in 5.1 cells by Western blot and the cell cycle by flow cytometry. Exponentially grown cells were treated with HU (2 mm) during 1, 3 or 6 h, or with PMA (50 ng/ml) in the presence of HU (2 mm) for 6 h, and cellular proteins extracted as indicated in Materials and Methods. In Fig. 5a it is shown that in untreated 5.1 cells pRB is present mainly in its hyperphosphorylated form, while a clear increase in dephosphorylated pRB was found in HU-treated cells, which was more evident after 6 h of treatment. It was also found that treatment with PMA in the presence of HU accelerated the dephosphorylation of the pRB. When the phosphorylation status of pRB was compared with the cell cycle, it was found that HU induced the arrest of the cell cycle after 24 h of treatment (the cells did not proceed to phase M), while the cell cycle did not change after 3 h or 6 h of HU treatment when compared with untreated 5.1 cells (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

(a) Hydroxyurea (HU) induces dephosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein. Cellular extracts from either HU (2 mm) or phorbol myristate acetate (PMA; 50 ng/ml) plus HU-treated 5.1 cells at the indicated times, were subjected to SDS–PAGE electrophoresis, and the retinoblastoma protein detected by Western blot (ppRB, hyperphosphorylated protein; pRB, phosphorylated protein; RB, unphosphorylated protein). (b) HU induces cell cycle arrest in 5.1 cells. Exponentially growing cells were incubated with HU (2 mm) and harvested at the indicated times. The cell cycle analysis was studied by propidium iodide staining and evaluated by flow cytometry. The percentages of cells in phase S and G2/M are indicated.

HU inhibits the binding of NF-κB to DNA

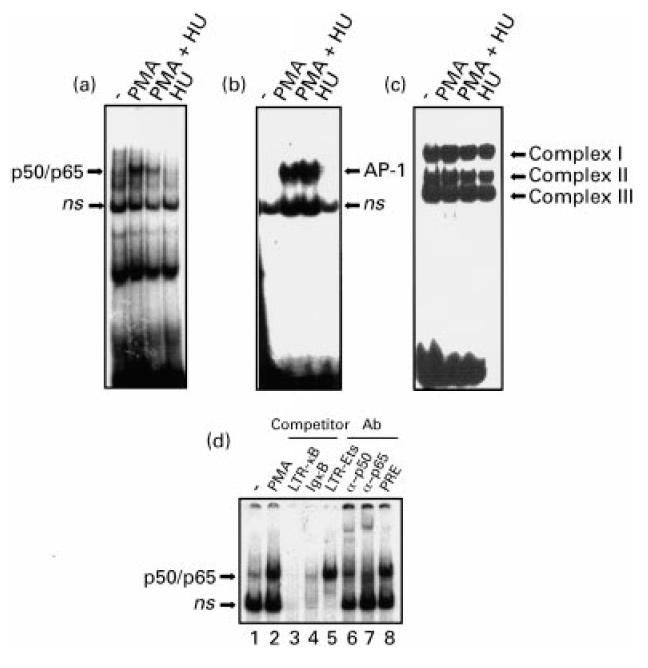

The promoter proximal region of the HIV-1-LTR contains two NF-κB binding sites that are required for inducible HIV gene expression in activated T cells and mature monocytes [10–13]. To study the role of NF-κB in the inhibition of HIV gene transcription by HU in 5.1 cells, we stimulated the cells with PMA (50 ng/ml) for 2 h in the presence or absence of HU (2 mm). Nuclear extracts were obtained and the binding to the κB sites in the HIV-LTR promoter (Fig. 6a), to an AP-1 site (Fig. 6b) and to an Sp1 site (Fig. 6c) was measured by EMSA assays using specific 32P-labelled double-stranded oligonucleotides (see MATERIALS and METHODS). An increase in the binding of nuclear proteins to the NF-κB sites was detected in nuclear extracts from PMA-stimulated 5.1 cells (Fig. 6a). The specificity and identification of this complex was demonstrated by cold competition with an excess of cold oligonucleotides, and by supershift experiments with the specific antisera anti-p50 and anti-p65. The results shown in Fig. 6d demonstrate that the binding proteins were composed of p50/p65 heterodimers. Interestingly, the binding of NF-κB was almost completely inhibited by HU (Fig. 6a), while under the same conditions the binding of inducible AP-1 to DNA was not affected by HU in PMA-stimulated 5.1 cells (Fig. 6b). When the binding of Sp1 transcription factor to DNA was studied, three specific complexes were found that bind to DNA in untreated 5.1 cells, and the binding of these complexes was not affected by PMA treatment either in the presence or absence of HU (2 mm) (Fig. 6c).

Fig. 6.

Effects of hydroxyurea (HU) on the DNA binding activity of Sp-1, NF-κB and AP-1 transcription factors. 5.1 cells were stimulated as indicated and nuclear extracts subjected to electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) analyses using different end-labelled oligonucleotides containing binding sites for NF-κB, LTR-κB (a), AP-1 (b), and Sp1 (c). ns, Non-specific. (d) Characterization of the phorbol myristate acetate (PMA)-induced NF-κB–DNA complexes. 5.1 cells were stimulated with PMA (50 ng/ml) for 2 h and nuclear extracts analysed by EMSA using a 32P-labelled DNA probe specific for the NF-κB site of the HIV-LTR promoter. Excess (100-fold) of LTR-κB cold oligonucleotide (lane 3), IgκB (lane 4), or LTR-Ets (lane 5) was used to determine the specificity of binding. The characterization of the specific complexes was performed with the specific antibodies anti-p50 (lane 6), anti-p65 (lane 7) or a preimmune antiserum (lane 8).

DISCUSSION

We demonstrate in this study that HU effectively inhibits the HIV-1-LTR transactivation induced by either PMA or TNF-α in lymphoid and non-lymphoid cells. This inhibition was dose-dependent, with a 50% inhibitory concentration of 0·5 mm, a plasma concentration well tolerated by patients with oncological diseases [42].

The use of HU in HIV-1 treatment has been controversial [43]. Several clinical studies of hydroxyurea-based drug combinations have been concluded, and the results have shown that HU alone neither affects the HIV-1 plasma viraemia nor increases the total number of CD4+ cells. In contrast, a combination of HU with nucleoside analogues (ddI or d4T) resulted in many cases in a prolonged decrease of the plasma viraemia [44–46]. HU effectively disrupts DNA synthesis in dividing cells by reducing the pool of available deoxyribonucleotides, and in so doing the viral reverse transcriptase cannot make functional viral products. Moreover, the nucleoside analogues will incorporate more rapidly to the new viral template stopping its synthesis [33,34]. Interestingly, it has been shown that a decrease in the intracellular pool of dNTPs mediated by HU also has an inhibitory effect on lamivudine-resistant variants of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase enzyme [47]. A possible limitation for such therapy may come from the side-effects of HU, bone marrow suppression being one of the more frequent side-effects [25]. This may explain why in some patients that received HU in combination with ddI or d4T, the decrease in viral RNA load did not correlate with a clear increase in the total number of peripheral CD4+ cells.

TNF-α, a pleiotropic inflammatory cytokine produced mainly by activated macrophages, is now recognized as a key pathogenic mediator of inflammatory and infectious diseases, including AIDS [48]. It has been shown that HIV-1 infection dysregulates the immune system, leading to abnormal production of TNF-α in AIDS patients [49,50]. Thus, the inhibition of the production and/or the effects of this cytokine has been for a while one of the strategies in AIDS therapy in combination with anti-retrovirals [51,52]. Our results show that HU effectively inhibits HIV-1-LTR transactivation in TNF-α-treated cells, but it does not inhibit the signalling pathways activated by this cytokine, since neither AP-1 activation nor CD69 induction was inhibited by HU. The molecular mechanisms by which HU inhibits HIV-1-LTR transactivation are not known. Nevertheless, the inhibition of the HIV-LTR occurs in the first 6 h of treatment. In this time the cell cycle is not affected, but a dephosphorylation of the pRB is evident. It has been shown that pRB in its unphosphorylated form interacts with the p50 subunit of the NF-κB family and suppresses its transcriptional activity [53]. Thus, in our model it is possible that pRB, which is a ubiquitously expressed nuclear protein, may interact with the p50 subunit of the NF-κB complex, inhibiting its function. Nevertheless, this effect would imply a general mechanism of NF-κB inhibition that is not the case for HU. We found that HU did not affect TNF-α induction of CD69, an effect that is mediated by NF-κB activation [36]. Moreover, HU did not inhibit the transcriptional activation of a plasmid containing the luciferase gene driven by three multimerized NF-κB sites from the IgκB promoter (data not shown). Kundu et al. have shown that the transcription factor E2F-1 is able to bind specifically to a site embedded within the two NF-κB elements of the HIV-1-LTR promoter [54]. In addition, E2F-1 can also interact with the p50 subunit repressing NF-κB-mediated transcription in cell free system [54], and inhibits Tat-induced LTR transactivation [55]. Thus, it is possible that pRB dephosphorylated by HU can bind to E2F-1 and also interact with the p50 subunit of NF-κB, preventing its binding to DNA and its transcriptional activity. We are actually performing experiments to study this hypothesis. Another possibility is that pRB dephosphorylation by HU is mediated by the induction of p53 tumour suppressor gene product through an increase of p21cip expression [56], and it has been shown that in some conditions p53 can also inhibit HIV-1-LTR transcription [57]. Although HeLa cells are p53-defective, this suppressor gene may have a potential role in the inhibition of HIV-1-LTR transactivation by HU in normal cells. In addition, we cannot rule out that the inhibitory effects of HU on the HIV-1-LTR transactivation are mediated by the arrests of cells at the phase G0/G1 of the cell cycle. In this context, it has been shown recently that the viral Vpr protein arrests cells in G2 phase of the cell cycle and can indirectly up-regulate HIV-1-LTR transcription [58]. Thus, it is possible that different nuclear factors involved in the progression of the cell cycle may act on the HIV-1-LTR promoter regulating its transcriptional activity.

In conclusion, we show here that HU inhibits HIV-1-LTR transactivation through a pathway independent of the inhibition of the ribonucleoside reductase and probably related to the dephosphorylation of the pRB. These results provide a new insight into the use of HU in AIDS therapy, mainly in the cases where serum levels of TNF-α are elevated.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by CICYT grant SAF98-0046 to E.M. The authors wish to thank Dr Nicole Isräel (Institute Pasteur, Paris, France) for the 5.1 cell line, Dr Alain Isräel (Institute Pasteur, Paris, France) for the gift of anti-p50 and anti-p65 antiserum, Dr Manuel Lopez-Cabrera (Hospital de la Princesa, Madrid, Spain) for the AIM-170 plasmid and Ms Carmen Cabrero-Doncel for assistance with the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zagury D, Bernard J, Leonard R, Cheynier R, Feldman M, Sarin PS, Gallo RC. Long-term cultures of HTLV-III-infected T cells: a model of cytopathology of T-cell depletion in AIDS. Science. 1986;231:850–3. doi: 10.1126/science.2418502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Folks T, Kelly J, Benn S, et al. Susceptibility of normal human lymphocytes to infection with HTLV-III/LAV. J Immunol. 1986;136:4049–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fauci AS, Schnittman SM, Poli G, Koenig S, Pantaleo G. NIH conference. Immunopathogenic mechanisms in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection; Ann Intern Med; 1991. pp. 678–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenberg ZF, Fauci AS. Induction of expression of HIV in latently or chronically infected cells. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1989;5:1–4. doi: 10.1089/aid.1989.5.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poli G, Kinter A, Justement JS, Kehrl JH, Bressler P, Stanley S, Fauci AS. Tumor necrosis factor alpha functions in an autocrine manner in the induction of human immunodeficiency virus expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:782–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.2.782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monté D, Groux H, Raharinivo B, et al. Productive human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection of megakaryocytic cells is enhanced by tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Blood. 1992;79:2670–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clouse KA, Powell D, Washington I, et al. Monokine regulation of human immunodeficiency virus-1 expression in a chronically infected human T cell clone. J Immunol. 1989;142:431–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poli G, Fauci AS. The effect of cytokines and pharmacologic agents on chronic HIV infection. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1992;8:191–7. doi: 10.1089/aid.1992.8.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaynor R. Cellular transcription factors involved in the regulation of HIV-1 gene expression. AIDS. 1992;6:347–63. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199204000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cullen BR. Regulation of human immunodeficiency virus replication. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1991;45:219–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.45.100191.001251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin R, Gewert D, Hiscott J. Differential transcriptional activation in vitro by NF-kappa B/Rel proteins. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:3123–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.7.3123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia JA, Gaynor RB. The human immunodeficiency virus type-1 long terminal repeat and its role in gene expression. Prog Nucl Acid Res Mol Biol. 1994;49:157–96. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones KA, Peterlin BM. Control of RNA initiation and elongation at the HIV-1 promoter. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:717–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.003441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grilli M, Chiu JJ, Lenardo MJ. NF-kappa B and Rel: participants in a multiform transcriptional regulatory system. Int Rev Cytol. 1993;143:1–62. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61873-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thanos D, Maniatis T. NF-kappa B: a lesson in family values. Cell. 1995;80:529–32. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90506-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verma IM, Stevenson JK, Schwarz EM, Van Antwerp D, Miyamoto S. Rel/NF-kappa B/I kappa B family: intimate tales of association and dissociation. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2723–35. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.22.2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baeuerle PA, Baltimore D. NF-kappa B: ten years after. Cell. 1996;87:13–20. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Régnier CH, Song HY, Gao X, Goeddel DV, Cao Z, Rothe M. Identification and characterization of an IkappaB kinase. Cell. 1997;90:373–83. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80344-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mercurio F, Zhu H, Murray BW, et al. IKK-1 and IKK-2: cytokine-activated IkappaB kinases essential for NF-kappaB activation. Science. 1997;278:860–6. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woronicz JD, Gao X, Cao Z, Rothe M, Goeddel DV. IkappaB kinase-beta: NF-kappaB activation and complex formation with IkappaB kinase-alpha and NIK. Science. 1997;278:866–9. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richman DD. Resistance, drug failure, and disease progression. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1994;10:901–5. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hammer SM, Kessler HA, Saag MS. Issues in combination antiretroviral therapy: a review. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1994;7:S24–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montaner JS, Hogg RS, O'Shaughnessy MV. Emerging international consensus for use of antiretroviral therapy. Lancet. 1997;349:1042. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)62289-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao WY, Cara A, Gallo RC, Lori F. Low levels of deoxynucleotides in peripheral blood lymphocytes: a strategy to inhibit human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8925–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.8925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donehower RC. An overview of the clinical experience with hydroxyurea. Semin Oncol. 1992;19:11–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lori F, Malykh A, Cara A, Sun D, Weinstein JN, Lisziewicz J, Gallo RC. Hydroxyurea as an inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus-type 1 replication. Science. 1994;266:801–5. doi: 10.1126/science.7973634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alter BP, Gilbert HS. The effect of hydroxyurea on hemoglobin F in patients with myeloproliferative syndromes. Blood. 1985;66:373–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cortelazzo S, Finazzi G, Ruggeri M, Vestri O, Galli M, Rodeghiero F, Barbui T. Hydroxyurea for patients with essential thrombocythemia and a high risk of thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1132–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199504273321704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Najean Y, Rain JD. Treatment of polycythemia vera: the use of hydroxyurea and pipobroman in 292 patients under the age of 65 years. Blood. 1997;90:3370–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steinberg MH, Nagel RL, Brugnara C. Cellular effects of hydroxyurea in Hb SC disease. Br J Haematol. 1997;98:838–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.3173132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charache S, Terrin ML, Moore RD, Dover GJ, Barton FB, Eckert SV, McMahon RP, Bonds DR. Effect of hydroxyurea on the frequency of painful crises in sickle cell anemia. Investigators of the Multicenter Study of Hydroxyurea in Sickle Cell Anemia. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1317–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505183322001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malley SD, Grange JM, Hamedi-Sangsari F, Vila JR. Suppression of HIV production in resting lymphocytes by combining didanosine and hydroxamate compounds. Lancet. 1994;343:1292. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92182-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao WY, Johns DG, Mitsuya H. Anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 activity of hydroxyurea in combination with 2′,3′-dideoxynucleosides. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;46:767–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meyerhans A, Vartanian JP, Hultgren C, Plikat U, Karlsson A, Wang L, Eriksson S, Wain-Hobson S. Restriction and enhancement of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication by modulation of intracellular deoxynucleoside triphosphate pools. J Virol. 1994;68:535–40. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.1.535-540.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Israël N, Gougerot-Pocidalo MA, Aillet F, Virilizier JL. Redox status of cells influences constitutive or induced NF-kappa B translocation and HIV long terminal repeat activity in human T and monocytic cell lines. J Immunol. 1992;149:3386–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.López-Cabrera M, Muñoz E, Blázquez MV, Ursa MA, Santis AG, Sánchez-Madrid F. Transcriptional regulation of the gene encoding the human C-type lectin leukocyte receptor AIM/CD69 and functional characterization of its tumor necrosis factor-alpha-responsive elements. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:21545–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.37.21545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Macho A, Blázquez MV, Navas P, Muñoz E. Induction of apoptosis by vanilloid compounds does not require de novo gene transcription and activator protein 1 activity. Cell Growth Differ. 1998;9:277–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cebrián M, Yagüe E, Rincón M, López-Botet M, Landázuri MO, Sánchez-Madrid F. Triggering of T cell proliferation through AIM, an activation inducer molecule expressed on activated human lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1988;168:1621–37. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.5.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nicoletti I, Migliorati G, Pagliacci MC, Grignani F, Riccardi C. A rapid and simple method for measuring thymocyte apoptosis by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry. J Immunol Methods. 1991;139:271–9. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(91)90198-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weinberg RA. The retinoblastoma protein and cell cycle control. Cell. 1995;81:323–30. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wise DA, Brinkley BR. Mitosis in cells with unreplicated genomes (MUGs): cell cycle arrest G1/S. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1997;36:291–302. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1997)36:3<291::AID-CM9>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Belt RJ, Haas CD, Kennedy J, Taylor S. Studies of hydroxyurea administered by continuous infusion: toxicity, pharmacokinetics, and cell synchronization. Cancer. 1980;46:455–62. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800801)46:3<455::aid-cncr2820460306>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Romanelli F, Pomeroy C, Smith KM. Hydroxyurea to inhibit human immunodeficiency virus-1 replication. Pharmacotherapy. 1999;19:196–204. doi: 10.1592/phco.19.3.196.30913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rutschmann OT, Opravil M, Iten A, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of didanosine plus stavudine, with and without hydroxyurea, for HIV infection. The Swiss HIV Cohort Study. AIDS. 1998;12:F71–77. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199808000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cohen J. HIV supressed long after treatment. Science. 1997;227:1927. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5334.1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vila J, Nugier F, Barguès G, Vallet T, Peyramond D, Hamedi-Sangsari F, Seigneurin JM. Absence of viral rebound after treatment of HIV-infected patients with didanosine and hydroxycarbamide. Lancet. 1997;350:635–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)24035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Back NKT, Berkhout B. Deoxynucleoside triphosphate concentrations emphasize the processivity defect of lamivudine-resistant variants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2484–91. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.11.2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aggarwal BB, Natarajan K. Tumor necrosis factors: developments during the last decade. Eur Cytokine Netw. 1996;7:93–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Molina JM, Scadden DT, Byrn R, Dinarello CA, Groopman JE. Production of tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin 1 beta by monocytic cells infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:733–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI114230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lähdevirta J, Maury CPJ, Teppo AM, Repo H. Elevated levels of circulating cachectin/tumor necrosis factor in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Med. 1988;85:289–91. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(88)90576-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Makonkawkeyoon S, Limson-Pobre RN, Moreira AL, Schauf V, Kaplan G. Thalidomide inhibits the replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5974–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.5974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Odeh M. The role of tumour necrosis factor-alpha in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Intern Med. 1990;228:549–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1990.tb00278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tamami M, Lindholm PF, Brady JN. The retinoblastoma gene product (Rb) induces binding of a conformationally inactive nuclear factor-kappaB. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:24551–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kundu M, Guermah M, Roeder RG, Amini S, Khalili K. Interaction between cell cycle regulator, E2F-1, and NF-kappaB mediates repression of HIV-1 gene transcription. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:29468–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.47.29468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kundu M, Srinivasan A, Pomerantz RJ, Khalili K. Evidence that a cell cycle regulator, E2F1, down-regulates transcriptional activity of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 promoter. J Virol. 1995;69:6940–6. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6940-6946.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sawaya BE, Khalili K, Mercer WE, Denisova L, Amini S. Cooperative actions of HIV-1 Vpr and p53 modulate viral gene transcription. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:20052–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gualberto A, Hixon ML, Finco TS, Perkins ND, Nabel GJ, Baldwin As., Jr A proliferative p53-responsive element mediates tumor necrosis factor alpha induction of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3450–9. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gummuluru S, Emerman M. Cell cycle-mediated and Vpr-mediated regulation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 expression in primary and transformed cell lines. J Virol. 1999;73:5422–30. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5422-5430.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]