Abstract

DiGeorge syndrome (DGS) and velocardiofacial syndrome (VCFS) are associated with chromosome 22q11.2 deletion. Limited information is available on the T cell receptor (TCR) Vβ repertoire. We therefore investigated TCR Vβ families in lymphocytes isolated from blood and thymic samples of seven patients with DGS and seven patients with VCFS, all with 22q11.2 deletion. We also studied activities related to TCR signalling including in vitro proliferation, anti-CD3-induced protein tyrosine phosphorylation, and susceptibility to apoptosis. Reduced CD3+ T cells were observed in most patients. Spontaneous improvement of T cell numbers was detected in patients, 3 years after the first study. Analysis of CD4+ and CD8+ TCR Vβ repertoire in peripheral and thymic cells showed a normal distribution of populations even if occasional deletions were observed. Lymphoproliferative responses to mitogens were comparable to controls as well as anti-CD3-induced protein tyrosine phosphorylation. Increased anti-CD3-mediated apoptosis was observed in thymic cells. Our data support the idea that in patients surviving the correction of cardiac anomalies, the immune defect appears milder than originally thought, suggesting development of a normal repertoire of mature T cells.

Keywords: DiGeorge syndrome, velocardiofacial syndrome, thymus, TCR repertoire, TCR signalling, apoptosis

INTRODUCTION

The DiGeorge syndrome (DGS) has been described as an immunodeficiency disease characterized by abnormal development of the third and fourth branchial pouches, resulting in thymic aplasia, parathyroid hypoplasia and cardiac abnormalities [1,2]. Infants with DGS may have some thymic rudiment and reduced number of functional T cells. A minority of cases presents with no thymus and absence of peripheral T cells. Approximately 90% of DGS is associated with chromosome 22q11.2 deletion [3,4] that disrupts the UFD1L gene [5–7].

The 22q11.2 deletion may present with other phenotypes including velocardiofacial syndrome (VCFS) [8–10]. VCFS is characterized by cleft palate or velopharyngeal insufficiency, cardiac anomalies, characteristic facies, learning disabilities, but presence of the thymus [11,12].

A few DGS cases have defects in other chromosomes, notably 10p13 [13,14].

In recent years, limited information has been reported on the immune defect in patients with chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndromes [15–20]. In particular, the lack of detailed studies of T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire in residual T cells of DGS patients is surprising because of the possible relevance of this information in understanding T cell differentiation and, consequently, pathogenesis of the disease.

Recently, a restricted TCR Vβ repertoire has been found by Collard et al. [21] in a case of complete DGS. Moreover, a repertoire restriction has been shown in the nude mouse, an animal model resembling DGS [22].

In our study we have grouped together all patients with 22q11.2 deletion irrespective of the phenotype (DGS or VCFS). This was supported by available immunological data showing that impaired T cell production and function are similar in patients with chromosome 22q11.2 deletion [23] and by involvement of UFD1L in the pathogenesis of the diseases [7].

We investigated the TCR Vβ repertoire in lymphocytes isolated from blood and rudimentary thymic samples. We also studied some of the functional activities related to TCR signalling, including (i) in vitro proliferation; (ii) phosphorylation pathway in response to anti-CD3 stimulation; and (iii) susceptibility to apoptosis. In addition, since it has been shown that oncostatin M may contribute to extrathymic differentiation [24,25], we analysed serum levels of this cytokine.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

Fourteen patients with 22q11.2 deletion were studied, seven with DGS and seven with VCFS. Nine were females and five were males. The mean age was 30 months (range 1–96 months). All patients had clinical and phenotypical anomalies of DGS/VCFS. The presence of the thymus was assessed at time of cardiac surgery. A small fragment of thymus was found in an ectopic location only in two of seven patients with DGS. In all patients with VCFS the thymus appeared normal. The control group included 12 age-matched patients, eight females and four males. All were negative for 22q11.2 deletion and had a congenital heart defect (CHD).

Deletions of 22q11.2 were investigated in all patients by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis on metaphase chromosomes prepared from peripheral blood lymphocytes as previously reported in detail [26].

Parental permission was obtained for all tested subjects according to the guidelines of informed consent approved by the Ethic Committee of the Hospital ‘Bambino Gesu’, Rome.

Isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells and surface phenotyping

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated from heparinized venous blood by Ficoll–Isopaque (FI) gradient (Lymphoprep Nycomed, Oslo, Norway). Immunophenotyping of freshly isolated PBMC was performed as previously reported in double or triple fluorescence [27], with an Ortho Cytoron fluorimeter (Ortho Diagnostics Systems, Inc., Raritan, NJ). MoAbs used included: anti-CD3–FITC, -CD4–PE, -CD8-peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP), anti-CD7 (FITC), anti-TCR-α/β (FITC), anti-TCR-γ/δ (FITC), anti-CD2 (FITC), anti-CD28 (PE), anti-CD38 (PE), anti-CD95 (FITC) (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA). Absolute lymphocyte counts were calculated by standard techniques.

For the purpose of this study, according to Hannet et al. [28] patients were described as having impaired T cell production if their CD3 count was < 62% and < 1800/μ l. A defect of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell counts was also considered when CD4 were < 30% and < 1000/μ l and when CD8 were < 25% and < 800/μ l. These are the 5% confidence limits for children between the ages of 1 and 6 years, which is the age range of 70% of the studied population.

Results were analysed with Student's t-test.

TCR phenotypic analysis

This was performed in triple fluorescence on an Ortho Absolute cytometer on PBMC from five patients (three with DGS and two with VCFS) and from five age-matched controls. The following MoAbs were purchased from Immunotech (Marseille, France) with the exception of anti-Vβ6.7 obtained from Serotec (Oxford, UK): Vβ2, -3, -5.1, -5.2, -5.3, -6.7, -7, -8, -9, -11, -12, -13.1, -13.6, -14, -16, -17, -18, -20, -21.3, -22, -23. All the MoAbs were used in an indirect immunofluorescence assay with a PE-labelled goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Dako, Carpinteria, CA). Anti-CD4–FITC and anti-CD8–PerCP were purchased from Becton Dickinson (San Jose, CA).

We also analysed the thymocytes derived from a rudimentary thymus obtained at time of cardiac surgery from two DGS patients and from two controls with 22q-unrelated deletion cardiopathy. Thymic tissue was minced carefully, thymocytes isolated through a FI gradient and analysed as described above.

Evaluation of spontaneous or induced apoptosis

Spontaneous apoptosis was detected as previously reported with slight modifications [29,30]. In brief, thymocytes were isolated through a FI gradient with standard techniques. Cells were incubated in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco Labs, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), glutamine and antibiotics in a CO2 incubator at 37°C for 24 h in a 24-well plate at a concentration of 4 × 105 cells/ml, in duplicate. At the beginning of the culture (day 0) and 24 h later, cells were removed from the well by careful pipetting, and stained with ethidium bromide (0·5 μ g/ml). At least 1000 cells were run through a cytofluorometer (Cytoron Absolute; Ortho Diagnostic Systems) to evaluate the absolute number of viable cells (i.e. cells not stained with ethidium). Percent mortality rate (MR) was calculated by the following formula: 100 − ((absolute number of viable cells at day 3)/(absolute number of viable cells at day 0)) × 100.

Apoptotic cells appear as a discrete population characterized by smaller size (mean forward scatter, 62) and increased granularity (mean right scatter, 33) in comparison with viable cells (mean forward scatter, 100, and mean right scatter, 19), and bright staining with ethidium.

Anti-CD3- and anti-Fas-induced apoptosis was assessed in 24-h culture as described above; anti-CD3 (clone UCHT1, PharMingen, San Diego, CA, used at the concentration of 0·1 μ g/ml) and anti-Fas (IgM CH-11 antibody, obtained from UBI, Lake Placid, NY and used at the concentration of 1 μ g/ml) were added to the cells at the beginning of the cultures.

In vitro lymphoproliferative responses

Cell proliferation was performed as previously reported [31]. In brief, PBMC were plated (2 × 105/well) in triplicate in 96-well tissue culture plates (Falcon, Becton Dickinson, Lincoln Park, NJ) and cultured for 3 days in RPMI 1640 with 10% FCS and antibiotics. Cultures were stimulated with phytohaemagglutinin (PHA, used at 1 μ g/ml and purchased from Sigma, St Louis, MO) and anti-CD3 (supernatants of clone OKT3, used at appropriate dilutions). Tritiated thymidine (Amersham, Aylesbury, UK) incorporation was measured on day 3, after addition of 1 μ Ci/well 4 h before terminating the cultures, in a β counter (Packard Instruments, Inc., Downers Grove, IL).

Evaluation of tyrosine phosphorylation induced by anti-CD3 MoAb

This was performed as previously reported [32]. Briefly, 107 PBMC/ml were cultured in medium alone or in the presence of anti-CD3 MoAb. After 5 min, cells were lysed in a buffer containing 20 mm Tris pH 8·0, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 1% NP-40, 1 mm PMSF, 100 μ g/ml aprotinin, 20 μ g/ml leupeptin and 1 mm sodium vanadate at 4°C for 30 min. Supernatants were clarified by centrifugation at 4°C for 15 min at 10 000 g. Protein content was determined by a colourimetric assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Fifteen micrograms protein per sample were separated on 10% SDS–PAGE followed by electrophoretic transfer onto nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond C; Amersham). After transfer, residual binding sites were blocked with 2% gelatin in TBS (10 mm Tris pH 8·0, 150 mm NaCl) for 1 h at 25°C. The filters were then incubated overnight with anti-phosphotyrosine MoAb (UBI) at 1 µ g/ml, in TBS–T (TBS with 0·05% Tween 20), washed twice and incubated for 1 h with 125I-labelled F(ab′)2 sheep anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Amersham) 1 μ Ci/ml in TBS–T. Finally, blots were exposed to x-ray film for 1–2 days.

Detection of serum levels of oncostatin M

Levels of oncostatin M were determined on sera collected and stored at −80°C. Sera were obtained from 17 patients (four with DGS and 13 with VCFS) and from 17 age-matched controls (each group included some subjects not available for other tests). Sera were concentrated × 2 on Microcon-10 microconcentrators (Amicon, Beverly, MA) and then tested for oncostatin M levels in ELISA using the Quantikine h-onc-M kit (R&D, Minneapolis, MN), according to the manufacturer's specification. Results were analysed with Student's t-test.

RESULTS

Analysis of lymphocyte populations

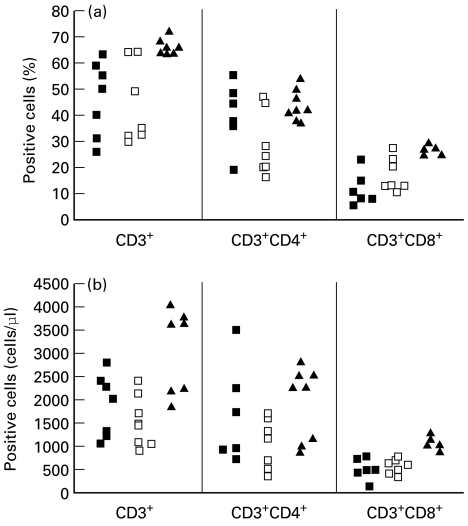

Both DGS and VCFS patients showed significantly reduced CD3+ T cells when compared with controls (P < 0·05). CD3 T cell count was 1895 ± 660 cells/μ l (46 ± 14%) in DGS patients and 1488 ± 544 cells/μ l (43 ± 16%) in VCFS patients versus 2915 ± 1055 cells/μ l (65 ± 3%) in controls. The CD4+ T cell count was not significantly different in DGS and VCFS patients from controls. In contrast, a significant decrease in CD8+ T cell count was observed in both groups of patients compared with controls (P < 0·01): 490 ± 235 cells/μ l (12 ± 7%) in DGS patients and 594 ± 179 cells/μ l (17 ± 6%) in VCFS patients versus 986 ± 129 cells/μ l (26 ± 1%) in controls. Detailed data for each patient are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow cytometric analysis of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from DiGeorge syndrome (DGS; ▪) and velocardiofacial syndrome (VCFS; □) patients and from controls (▴) with 22q-unrelated congenital heart defect. Percentage (a) and absolute numbers (cells/μ l) (b) of CD3+, CD3+CD4+ and CD3+CD8+ cells. Not all the markers were studied in all tested subjects.

Three years after the first study, analysis of lymphocyte populations was repeated in three patients with lower levels of CD3+ T cells and normal T cell responses to mitogens. Spontaneous improvement of T cell subpopulations was observed. In particular, CD3+ T cells increased from 1150 ± 135 cells/μ l to 2146 ± 825 cells/μ l, CD4+ T cells from 658 ± 297 cells/μ l to 1269 ± 701 cells/μ l and CD8+ T cells from 591 ± 173 cells/μ l to 836 ± 82 cells/μ l. In agreement with improvement of immune parameters, during the follow-up period no increased susceptibility to infections was shown.

Phenotyping of TCR

This was evaluated on both CD4+ and CD8+ peripheral and thymic T cells with a panel of MoAbs covering approximately 60% of the Vβ repertoire. PBMC were obtained from five patients (three with DGS and two with VCFS) and from five age-matched controls. In two VCFS patients and in one DGS patient the analysis of Vβ TCR on both CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes did not show any perturbations of tested populations compared with controls (data not shown). Missing populations were found in the other two DGS patients (CD4 and CD8 Vβ5.2, CD4 and CD8 Vβ20 in one patient and CD8 Vβ9, CD8 Vβ13.1, CD4 and CD8 Vβ13.6 and CD8 Vβ18 in the other patient). These subjects showed the lowest levels of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells among the analysed patients.

A fragment of a rudimentary thymus was obtained when surgery was performed to correct CHD from two patients with DGS and from two controls with 22q11.2 deletion-unrelated CHD.

Phenotypic analysis showed no differences between patients and controls with the exception of double-positive (DP) T cells (CD4+CD8+) reduced in both patients (30% and 42%, respectively, versus 79 ± 2% of controls) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Phenotype of lymphoid cells derived from thymic tissues obtained from two DiGeorge syndrome (DGS) patients and from two controls with 22q-unrelated congenital heart defect

| CD7 | CD4+CD8+ | CD4+CD8− | CD4−CD8+ | α/β | γ/δ | CD2 | CD28 | CD38 | CD95 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | 97 | 30 | 48 | 14 | 89 | 1 | 97 | 82 | 97 | 4 |

| Patient 2 | 97 | 42 | 35 | 17 | 64 | 2 | 98 | 56 | 98 | 3 |

| Controls | 95 ± 2 | 79 ± 2 | 10 ± 1 | 11 ± 1 | 55 ± 3 | 1 ± 0·8 | 98 ± 1 | 83 ± 5 | 96 ± 1 | 3 ± 1 |

Results are given as individual percentage of positive cells in patients and as mean percentage (± s.d.) in controls.

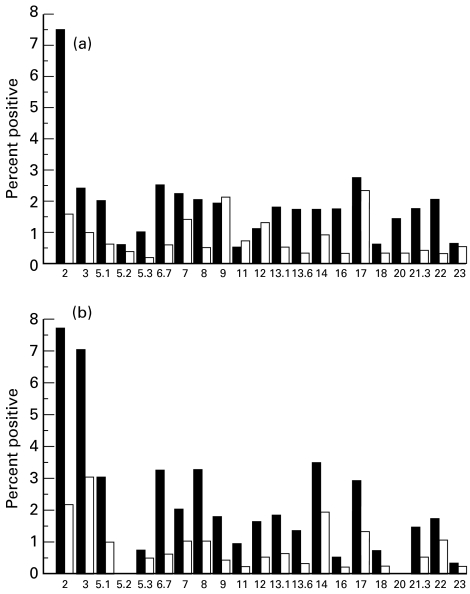

Analysis of the frequency of Vβ populations was also performed. One patient (Fig. 2a) had no significant perturbation of Vβ populations compared with controls. The other patient (Fig. 2b) showed the same undetectable TCR families (CD4 and CD8 Vβ5.2, CD4 and CD8 Vβ20) observed in peripheral T cells.

Fig. 2.

T cell receptor (TCR) Vβ repertoire as measured by flow cytometry of thymic CD4+ (▪) and CD8+ (□) T cells from two DiGeorge syndrome (DGS) patients. Patient (a) had no significant perturbation of Vβ populations compared with normal controls (data not shown). Missing populations were shown in patient (b) (CD4 and CD8 Vβ5.2, CD4 and CD8 Vβ20). In this patient the same undetectable Vβ families were observed in peripheral T cells.

Apoptosis

Apoptosis of lymphoid cells from thymic tissues obtained from two patients with DGS and from two controls was also evaluated. In both patients spontaneous apoptosis (14 ± 1%) and CD3- and Fas-mediated apoptosis (27 ± 7% and 20 ± 3%, respectively) was reduced when compared with controls (47 ± 22%, 59 ± 25% and 52 ± 41%, respectively). CD3- and Fas-mediated apoptosis was increased, although not significantly, in comparison with spontaneous apoptosis in all tested cases.

Lymphoproliferative responses to mitogens and anti-CD3-induced tyrosine phosphorylation pathway

Lymphoproliferative responses to PHA and to anti-CD3 were normal in all tested patients compared with controls (PHA > 75 000 ct/min and anti-CD3 > 55 000 ct/min). Anti-CD3-induced protein tyrosine phosphorylation was also studied in two DGS patients and compared with that induced by the same treatment in one normal control. The pattern of tyrosine phosphorylated proteins observed in DGS patients was not significantly different from that observed in controls (data not shown).

Detection of serum levels of oncostatin M

Oncostatin M was detectable in sera from nine out of 17 patients (three out of four DGS patients, six out of 13 VCFS patients) and from three out of 17 controls. Mean level (± s.e.m.) of oncostatin M was 8·8 ± 5·8 pg/ml in DGS patients, 4 ± 2·2 pg/ml in VCFS patients (P > 0·05 versus DGS patients) and 0·6 ± 1·6 pg/ml in controls (P < 0·05 versus DGS patients and P > 0·05 versus VCFS patients).

DISCUSSION

Fourteen patients with chromosome 22q11.2 deletion (seven with DGS and seven with VCFS) were studied. Flow cytometric analysis of PBMC showed a reduction in T cells in both groups of patients. TCR Vβ repertoire expressed by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells isolated from blood and rudimentary thymic samples presented a normal distribution of Vβ families with occasional deletions observed. Lymphoproliferative responses in vitro to a variety of stimuli were also normal as well as anti-CD3-induced protein tyrosine phosphorylation. Anti-CD3-mediated apoptosis was increased compared with spontaneous apoptosis.

Our results support the idea that the T cell defect, measured by a variety of phenotypic and functional tests, is mild in most patients with 22q11.2 deletion. In addition, the defect tends to decrease with time, as shown by our analysis which was repeated. These data are in accordance with previous reports that patients who have low T cell numbers but normal T cell responses to mitogens can spontaneously demonstrate an increase in T cell numbers [2,33]. We agree with Markert et al. [34], that immunorestorative therapy should not be considered for patients with low T cell numbers if there is a good response to mitogens. In contrast, in patients with a profound decrease in immune function, such as those studied by Markert et al., early thymic transplantation should be performed [35,36].

In recent years it has become possible to investigate the repertoire of TCR specificities by the measurement of T lymphocytes expressing the different Vβ families. Although a few populations were occasionally missing, in most of our samples the different Vβ populations were normally present. However the observation of a normal size of individual TCR Vβ families does not imply a normal repertoire. Further studies by molecular biology-based techniques, such as the fragment size analysis of the third complementary determining region (CDR3 spectratyping), are needed to acquire further information on the distribution of TCR Vβ families [37–39].

A few TCR Vβ families were occasionally missing in our patients (Vβ5.2, Vβ20, Vβ9, Vβ13.1, Vβ13.6 and Vβ18). Recent studies [36] showed in one DGS patient, before and after thymus transplantation, no CD3 T cells expressing Vβ5.2 and other TCR Vβ families different from those observed by us. Previous studies showed that even modest allelic variation in human TCR Vβ coding regions can have a significant impact on the expression of human Vβ genes in the peripheral repertoire [40]. These polymorphisms, already described for Vβ3 and Vβ6.7 [40–42], could be responsible for the deletions of TCR Vβ families observed in our patients.

Our data are different from those obtained in the animal model where a restricted repertoire was found [22]. A repertoire restriction was also reported in a case of complete DGS [21]. However, these interesting findings were limited to one patient who had no detectable thymus tissue and profound T cell dysfunction, as shown by the extremely low response to mitogen stimulation.

We also evaluated some functional activities related to TCR signalling. No significant differences were observed in either DGS or VCFS patients compared with controls.

In two DGS patients we also analysed anti-CD3-mediated apoptosis of thymic cells, another functional activity related to TCR signalling. The increased level of apoptosis observed in our samples support the notion that activation of immature thymocytes via their TCR induces apoptosis rather than proliferation in these cells [43].

Since apoptosis is a mechanism involved in organ modelling [44] it could be hypothesized that patients with the absence of a normal thymic structure could present higher levels of spontaneous or CD3-induced apoptosis of thymocytes. On the contrary, our data suggest a reduction of both spontaneous and CD3- or Fas-mediated apoptosis in comparison with a normal thymus. These data are probably related to the reduction of more immature DP cells observed in DGS patients, which are more susceptible to apoptosis. Finally, the presence of relatively high numbers of T cells in patients with rudimentary thymus suggests that these fragments are sufficient to allow T cell differentiation. Furthermore, extrathymic lymphopoiesis may also be relevant in these patients. Recently, a role has been proposed for oncostatin M based on data obtained in mice transgenic for oncostatin M [25]. These animals develop mature T cells independently of the presence of the thymus [24]. In an attempt to identify if this mechanism could contribute to the development of T cells in DGS patients, we measured their serum levels of this cytokine and found them significantly higher in sera of DGS patients compared with controls. Further studies are required to confirm if over-production of oncostatin M is responsible for T cell development in these patients, and in which tissue T cell development takes place.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by MURST-cofin 1997–1998, grant no. E.723 from the Italian Telethon and grant no. 40A0.02, 1998, from the ‘Istituto Superiore di Sanita’. We thank doctors and nurses of the Unit of Cardiac Surgery of the Hospital Bambino Gesu' (Chief Dr R. Di Donato), Rome, Italy, for supplying thymic samples.

REFERENCES

- 1.DiGeorge A. Congenital absence of the thymus and its immunologic consequences: concurrence with congenital hypoparathyroidism. In: Good RA, Bergsma D, editors. Immunologic deficiency diseases in man, Birth Defects Original Article Series. Vol. 4. New York: New York National Foundation Press; 1968. pp. 116–21. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hong R. The DiGeorge anomaly. Immunodef Rev. 1991;3:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Driscoll DA, Budarf ML, Emanuel BS. A genetic etiology for DiGeorge syndrome: consistent deletions and microdeletions of 22q11. Am J Hum Genet. 1992;50:924–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carey AH, Kelly D, Halford S, et al. Molecular genetic study of the frequency of monosomy 22q11 in DiGeorge syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 1992;51:964–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pizzuti A, Novelli G, Ratti A, et al. UFD1L, a developmentally expressed ubiquitination gene, is deleted in CATCH 22 syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:259–65. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Novelli G, Mari A, Amati F, et al. Structure and expression of the human ubiquitin fusion-degradation gene (UFD1L) Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1396:158–62. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(97)00211-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamagishi H, Garg V, Matsuoka R, Thomas T, Srivastava D. A molecular pathway revealing a genetic basis for human cardiac and craniofacial defects. Science. 1999;283:1158–61. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5405.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Driscoll DA, Spinner NB, Budarf ML, et al. Deletions and microdeletions of 22q11.2 in velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1992;44:261–8. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320440237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Driscoll AD, Salvin J, Sellinger B, Budarf ML, MacDonald-MacGinn DM, Zackai EH, Emanuel BS. Prevalence of 22q11 microdeletions in DiGeorge and velocardiofacial syndromes: implications for genetic counseling and prenatal diagnosis. J Med Genet. 1993;30:813–7. doi: 10.1136/jmg.30.10.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelly D, Goldberg R, Wilson D, et al. Confirmation that the velo-cardio-facial syndrome is associated with haplo-insufficiency of genes at chromosome 22q11. Am J Med Genet. 1993;45:308–12. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320450306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldberg R, Motzkin B, Marion R, Scamber P, Shprintzen R. Velo-cardio-facial syndrome: a review of 120 patients. Am J Med Genet. 1993;45:313–9. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320450307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson DI, Burn J, Scambler P, Goodship J. DiGeorge syndrome: part of CATCH 22. J Med Genet. 1993;30:852–6. doi: 10.1136/jmg.30.10.852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daw S, Taylor C, Kramam M, et al. A common region of 10p deleted in DiGeorge and velocardiofacial syndromes. Nature Med. 1996;13:458–60. doi: 10.1038/ng0896-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pignata C, D'Agostino A, Finelli P, et al. Progressive deficiencies in blood T cells associated with a 10p12-13 interstitial deletion. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1996;80:9–15. doi: 10.1006/clin.1996.0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muller W, Peter H, Kallfelz H, Franz A, Rieger C. The DiGeorge sequence. II. Immunologic findings in partial and complete forms of the disorder. Eur J Pediatr. 1989;149:96–103. doi: 10.1007/BF01995856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Radford DJ, Perkins L, Lachman R, Thong YH. Spectrum of Di George syndrome in patients with truncus arteriosus: expanded Di George syndrome. Pediatr Cardiol. 1988;9:95–101. doi: 10.1007/BF02083707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slade HB, Greenwood JH, Beekman Rd McCoy JJ, Hudson JL, Pahwa S, Schwartz SA. Flow cytometric analysis of lymphocyte subpopulations in infants with congenital heart disease. J Clin Lab Anal. 1989;3:14–20. doi: 10.1002/jcla.1860030105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Junker AK, Driscoll DA. Humoral immunity in DiGeorge syndrome. J Pediatr. 1995;127:231–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(95)70300-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rhoden DK, Leatherbury L, Helman S, Gaffney M, Strong WB, Guill MF. Abnormalities in lymphocyte populations in infants with neural crest cardiovascular defects. Pediatr Cardiol. 1996;17:143–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02505203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta S, Aggarwal S, Nguyen T. Increased spontaneous apoptosis in T lymphocytes in DiGeorge anomaly. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;113:65–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collard HR, Boeck A, McLaughlin TM, Watson TJ, Schiff SE, Hale LP, Markert ML. Possible extrathymic development of nonfunctional T cells in a patient with complete DiGeorge syndrome. Clin Immunol. 1999;91:156–62. doi: 10.1006/clim.1999.4691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacDonald HR, Lees RD, Bron C, Sordat B, Meiescher G. T cell antigen receptor expression in athymic (nu/nu) mice. J Exp Med. 1987;166:195–209. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.1.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sullivan KE, Jawad AF, Randall JP, Driscoll DA, Emanuel BS, McDonald-McGinn DM, Zackai EH. Lack of correlation between impaired T cell production, immunodeficiency and other phenotypic features in chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndromes (DiGeorge syndrome /velocardiofacial syndrome) Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1998;86:141–6. doi: 10.1006/clin.1997.4463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clegg C, Rulffes J, Wallace P, Haugen H. Regulation of an extrathymic T-cell development pathway by oncostatin M. Nature. 1996;384:261–3. doi: 10.1038/384261a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Metcalf D. Another way to generate T cells? Nature Med. 1997;3:18–19. doi: 10.1038/nm0197-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pizzuti A, Novelli G, Mari A, et al. Human homologue sequences to the Drosophila dishevelled segment-polarity gene are deleted in the DiGeorge syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58:722–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pandolfi F, Trentin L, San MJ, Wong JT, Kurnick JT, Moscicki RA. T cell heterogeneity in patients with common variable immunodeficiency as assessed by abnormalities of T cell subpopulations and T cell receptor gene analysis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1992;89:198–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb06932.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hannet I, Erkeller-Yuksel F, Lydyard P, Deneys V, De Bruyere M. Lymphocyte populations as a function of age. Immunol Today. 1992;13:215–8. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pandolfi F, Oliva A, Sacco G, et al. Fibroblast-derived factors preserve viability in vitro of mononuclear cells isolated from subjects with HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 1993;7:323–9. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199303000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pandolfi F, Pierdominici M, Oliva A, et al. Apoptosis-related mortality in vitro of mononuclear cells from patients with HIV infection correlates with disease severity and progression. J AIDS. 1995;9:450–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pandolfi F, Foa R, De Rossi G, et al. Clonally expanded CD3+, CD4−, CD8− cells bearing the alpha/beta or the gamma/delta T-cell receptor in patients with the lymphoproliferative disease of granular lymphocytes. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1991;60:371–83. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(91)90094-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giovannetti A, Aiuti A, Pizzoli P, et al. Tyrosine phosphorylation pathway is involved in interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) production; effect of sodium ortho vanadate. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;100:157–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb03618.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bastian J, Law S, Volger L, et al. Prediction of persistent immunodeficiency in the DiGeorge anomaly. J Pediatr. 1989;115:391–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(89)80837-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Markert ML, Hummell DS, Rosenblatt HM, et al. Complete DiGeorge syndrome: persistence of profound immunodeficiency. J Pediatr. 1998;132:15–21. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70478-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Markert ML, Kostyu DD, Ward FE, et al. Successful formation of a chimeric human thymus allograft following transplantation of cultured postnatal human thymus. J Immunol. 1997;158:998–1005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Markert ML, Boeck A, Hale LP, et al. Transplantation of thymus tissue in complete DiGeorge syndrome. New Engl J Med. 1999;341:1180–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910143411603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pannetier C, Cochet M, Darche S, Casrouge A, Zoller M, Kourilski P. The sizes of the CDR3 hypervariable regions of the murine T cell receptor vary as a function of the recombined germ-line segments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4319–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.9.4319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maslanka K, Piatek T, Gorski J, Yassai M, Gorski J. Molecular analysis of T cell repertoires. Spectratypes generated by multiplex polymerase chain reaction and evaluated by radioactivity or fluorescence. Hum Immunol. 1995;44:28–34. doi: 10.1016/0198-8859(95)00056-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shen J, Andrews DM, Pandolfi F, et al. Oligoclonality of Vδ1 and Vδ2 cells in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells: TCR selection is not altered by stimulation with Gram-negative bacteria. J Immunol. 1998;160:3048–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vissinga CS, Charmley P, Concannon P. Influence of coding region polymorphism on the peripheral expression of a human TCR V beta gene. J Immunol. 1994;152:1222–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Y, Szabo P, Robinson MA, Dong B, Posnett DN. Allelic variations in the human T cell receptor V beta 6.7 gene products. J Exp Med. 1990;171:221–30. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.1.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Posnett DN, Vissinga CS, Pambuccian C, et al. Level of human TCRBV3S1 (V beta 3) expression correlates with allelic polymorphism in the spacer region of the recombination signal sequence. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1707–11. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.5.1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McConkey D, Hartzell P, Chow S, Orrenius S, Jondal M. Calcium-dependent killing of immature thymocytes by stimulation via the CD3/T cell receptor complex. J Immunol. 1989;143:1801–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kerr J, Wyllie A, Currie A. Apoptosis: a basic biological phenomenon with wide ranging implication in tissue kinetics. Br J Cancer. 1972;26:239–57. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1972.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]