Abstract

The human nuclear autoantigenic sperm protein, NASP, is a testicular histone-binding protein of 787 amino acids to which most vasectomized men develop autoantibodies. In this study to define the boundaries of antigenic regions and epitope recognition pattern, recombinant deletion mutants spanning the entire protein coding sequence and a human NASP cDNA sublibrary were screened with vasectomy patients' sera. Employing panel sera from 21 vasectomy patients with anti-sperm antibodies, a heterogeneous pattern of autoantibody binding to the recombinant polypeptides was detected in ELISA and immunoblotting. The majority of sera (20/21) had antibodies to one or more of the NASP fusion proteins. Antigenic sites preferentially recognized by the individual patients' sera were located within aa 32–352 and aa 572–787. Using a patient's serum selected for its reactivity to the whole recombinant protein in Western blots, cDNA clones positive for the C-terminal domain of the molecule were identified. The number and location of linear epitopes in this region were determined by synthetic peptide mapping and inhibition studies. The epitope-containing segment was delimited to the sequence aa 619–692 and analysis of a series of 74 concurrent overlapping 9mer synthetic peptides encompassing this region revealed four linear epitopes: amino acid residues IREKIEDAK (aa 648–656), KESQRSGNV (aa 656–664), AELALKATL (aa 665–673) and GFTPGGGGS (aa 680–688). All individual patients' sera reacted with epitopes within the sequence IRE….GGS (aa 648–688). The strongest reactivity was displayed by peptides corresponding to the sequence AELALKATL (aa 665–673). Thus, multiple continuous autoimmune epitopes in NASP involving sequences in the conserved C-terminal domain as well as in the less conserved testis-specific N-terminal region comprising the histone-binding sites, as predicted for an antigen-driven immune response, may be a target of autoantibodies in vasectomized men and may provide a relevant laboratory variable to describe more accurately the spectrum of autoantibody specificities associated with the clinical manifestation of vasectomy.

Keywords: autoantibodies, vasectomy, B cell epitopes, NASP

Introduction

Anti-nuclear autoantibodies have been instrumental as immunological probes in delineating the structural basis of autoimmunity to nuclear antigens including DNA, histones, nuclear enzymes and protein–RNA complexes [1,2]. Experimental approaches to dissect the fine specificity of antigenic determinants have relied on synthetic peptides [3–5] or have been performed with phage libraries [6–8]. Epitope mapping utilizing short synthetic peptides to identify continuous antigenic determinants originally described by Geysen [9,10] is a well-favoured, although sometimes controversial methodology [11], and has been applied to search systematically for linear epitopes in numerous antigens. Autoimmune epitopes have been determined for several nuclear autoantigens such as B/B′ [12], lamin B [13], Ku [14], (U1) RNP-associated protein [15], tRNA Ala [16], (U1) RNA [17], La [18,19], Ro [20,21], sp100 [22], topoisomerase II [23], and histones [24], which are involved in multisystemic autoimmune syndromes.

Considerably less information is available regarding the autoantigenicity of nuclear sperm and testis-specific proteins. The immunologically privileged status of the testis, and consequently of germ cell-specific antigens sequestered behind the blood–testis barrier, seems to be compromised under abnormal circumstances such as vasectomy. Since vasectomy is currently a widely used and the most cost-efficient male contraceptive [25], a better understanding of its immunological consequences is desirable. Following vasectomy, anti-sperm antibodies develop that have been implicated in reduced fertility following vasovasostomy [26–30]. The induction of antinuclear antibodies directed to the nuclear sperm-specific basic proteins, the protamines, and to a sperm-specific DNA-polymerase following vasectomy, has been reported [31–33]. We have reported the presence of antibodies to a human testicular nuclear autoantigenic sperm protein (NASP) in sera from vasectomized patients [34]. Testicular NASP cDNA has been cloned and sequenced and encodes a protein of deduced molecular mass of 86 190 D which is localized in primary spermatocytes and spermatids in rabbit [35–37] and human testes [38]. Testicular NASP (tNASP) is distinct from somatic NASP (sNASP) that occurs in several non-germ cell tissues [39]. Somatic NASP is a splice variant of tNASP and is identical except for the deletion of two separate regions that reduce the deduced molecular weight of somatic NASP to 45 752 D [39].

In our previous study [34] it was found that 18/21 vasectomized patients (86%) with anti-sperm antibodies had anti-tNASP autoantibodies. Consequently we have initiated the present study of a second group of vasectomized patients with anti-sperm antibodies in order to address the issue of the autoantigenic potential of continuous autoimmune epitopes on the primary sequence of testicular NASP. In the present study we have cloned and expressed the human gene encoding the protein. On the basis of the full-length cDNA, a series of truncation mutants has been designed and expressed in vitro and a human tNASP gene sublibrary of cDNA fragments with random endpoints was constructed in the expression vector λgt11. Using recombinant deletion mutants, two major immunogenic regions aa 32–352 and aa 572–787 have been identified. To map more precisely the location of linear autoepitopes, using an autoantibody selected cDNA clone the sequences of four minimal autoimmune epitopes in the C-terminal of tNASP are deduced. The C-terminal autoepitopes appear to be present on the surface of the intact, folded molecule, as evidenced by the ability of autoantibodies to bind to them in liquid-phase assays. The linear B cell epitopes have been localized using the mimotope format of immunoassay. Delineation of these autoimmune epitopes and their existence in other non-germ cell somatic NASP proteins should lead to a better understanding of the immunological reaction to vasectomy.

Materials and methods

Expression plasmid constructs

A human tNASP cDNA clone (2·411 kb) which did not contain a 5′-untranslated region and started three codons downstream of the initiation codon, aa 5–787 (Fig. 1), was isolated from a human testis cDNA library (Clontech Labs, Palo Alto, CA) [40]. The cDNA was recloned in the Eco RI site of the pBluescript vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and propagated in Escherichia coli strain DH 5α. For expression in E. coli, the coding region of NASP was blunted with Klenow fragment DNA polymerase and introduced in the Sma I site of the His-tag pQE 30 expression vector (Qiagen Inc., Chatsworth, CA) downstream of the original ATG initiation codon provided by the vector. N-terminal and C-terminal truncated mutants were generated either by utilizing restriction sites within the cDNA or by amplification of specific regions by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). All constructs were subcloned into the corresponding pQE expression vector (either pQE 30, 31, or 32) [40]. The following expression constructs were used: a Bam HI/Pst I fragment from nt 99–178 and a Bam HI/Pst I fragment from nt 99–661 were subcloned into pQE 30; two Pst I/Pst I fragments from nt 178–1141 and nt 178–661 were inserted in pQE-30, a Pst I/Hind III fragment from nt 1801–2510 was introduced in pQE-31. The subclones from nt 662–1141, nt 1142–1801 and nt 1802 were amplified by PCR using a Bam H1 site in the sense primer and a Kpn I site in the antisense primer and inserted into pQE-30. The reading frame and identity of the insert in each construct were validated by plasmid sequencing in both orientations by the dideoxy chain-termination method [41] using the Sequenase Version 2.0 T7 DNA polymerase (USB Corp., Cleveland, OH). The following deletion subclones were produced (Fig. 1) spanning: aa 5–31, aa 5–192, aa 32–192, aa 32–352, aa 193–352, aa 352–571, aa 571–787, aa 572–787. Recombinant pQE plasmids were propagated in E. coli M15 host cell line containing the pREP4 plasmid and the encoded proteins were expressed as IPTG-induced 6xHistidine tag fusion proteins. The recombinant proteins were affinity-purified by Ni-NTA chromatography (Qiagen Inc.) and the molecular size of the 5–787 tNASP and the expressed portions of the protein was verified by SDS–PAGE.

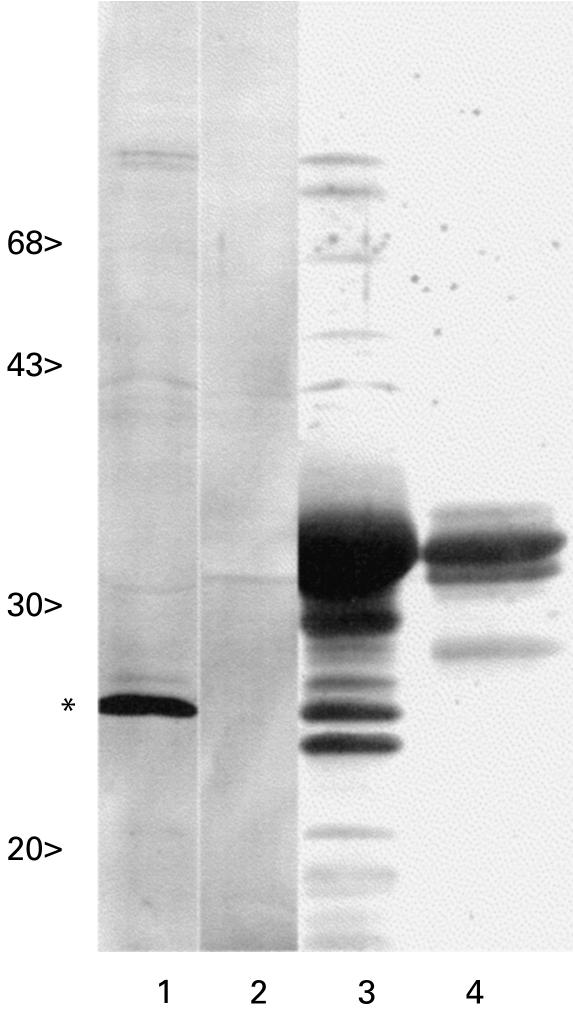

Fig. 1.

SDS–PAGE of recombinant human testicular nuclear autoantigenic sperm protein (tNASP) expression clones. Deletion subclones were generated and expressed as 6xHis-tagged fusion proteins. In addition to the full size protein fragments, shorter fragments representing prematurely terminated translation products were also detected: lane 1, molecular size markers; lane 2, tNASP, aa 5–787; lanes 3–10, deletion mutants, spanning the designated regions. The fragments expressed as recombinant proteins are indicated with amino acid no.; lane 11, a C-terminal recombinant fragment generated by cyanogen bromide cleavage (see text), aa 619–691.

Construction of λgt11 tNASP cDNA sublibrary and screening

The 2·411-kb Eco RI/Eco RI tNASP cDNA cloned in pBluescript KS+ was excised, purified and used to construct a gene sublibrary as described by Mehra et al. [6]. DNA was digested with DNase I, fractionated by agarose gel electrophoresis and the fragments of 100–800 bp were recovered and end-repaired with bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase. Blunt-ended fragments were then ligated to phosphorylated 8-mer Eco RI linkers (New England Biolabs, Inc., Beverly, MA), extensively digested with Eco RI and purified by agarose gel electrophoresis, phenol extraction and ammonium acetate precipitation. The linked DNA fragments were ligated into phosphatase-treated λgt11 arms (Gibco/BRL Corp., Gaithersburg, MD) and packaged into recombinant phage using Gigapack Gold II packaging extract (Statagene, La Jolla, CA). For screening, E. coli Y1090 was infected with the recombinant λgt11 phage and plated at a density sufficient to produce 1 × 103 plaques per 135 mm agar plate. Plates were incubated for 4 h at 42°C, overlaid with nitrocellulose filters soaked in 10 mm isopropyl-αd-thiogalactoside (IPTG), and transferred to 37°C overnight. After washing with TBS–Tween 20 (Tris-buffered saline, pH 7·5) and blocking in TBS−2% non-fat dry milk, the filters were incubated overnight at 4°C with a vasectomy patient's serum denoted as no. 15 (diluted 1:20 in TBS−1% bovine serum albumin (BSA)), that had been preabsorbed with E. coli bacterial lysate. The filters were washed with TBS–Tween and incubated with 125I-labelled protein A (1·5 μCi per filter) for 2 h at room temperature, washed, dried out and exposed using Kodak XAR x-ray film at −70°C. Several positive cDNA clones were selected with the human serum which all cross-hybridized with each other by Southern blotting.

Immunoblotting

Purified recombinant proteins or bacterial lysates were subjected to SDS–PAGE (10–14% gels) and transferred onto Immobilon P membranes (PVDF; Millipore, Bedford, MA) [42]. After blocking with 2% non-fat dry milk in TBS–T (TBS, 20 mm Tris–HCl, 0·5 m NaCl, pH 7·5, + 0·5% Tween), the membranes were washed and incubated in human sera diluted 1:100 in TBS–T−1% BSA or 1:500 diluted mouse immune sera raised against recombinant tNASP (aa 5–787). The washed membranes were incubated in alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-human immunoglobulin (IgM, IgG and IgA; 1:2000 dilution) or alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin (IgM, IgG and IgA). After washing, the reaction was developed with 30 mg/ml nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) and 15 mg/ml 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate-p-toluidine salt (BCIP; Sigma, St Louis, MO) in a 0·1-m NaHCO3, 1 mm MgCl2, pH 9·8 substrate buffer.

Affinity purification of autoantibodies

Affinity-purified human anti-tNASP autoantibodies were used in some experiments. Purified recombinant full-length NASP was electrophoresed in a 10% gel, transferred to Immobilon P membranes (Millipore) and the corresponding band was cut out, blocked and incubated in 1:100 diluted vasectomy patient's serum no. 15. Bound antibodies were eluted with 0·2 m glycine–HCl pH 2·5, and 1·0 m KH2PO4 pH 9·0 and 5% fetal calf serum (FCS) added. To reduce the ionic strength, 1 volume deionized water and 1/3 volume TBS were added and the final concentration of FCS in the antibody solution was made 20%.

Cyanogen bromide cleavage and high performance liquid chromatography

Recombinant protein (50 μg) expressing the C-terminal portion of tNASP solubilized in 0·1 N HCl was digested with 100 μg cyanogen bromide (CNBr)/ml HCOOH in the presence of 4% 2-mercaptoethanol for 2 h at room temperature. The sample was extensively washed with deionized water and dried in a speedvac. The peptides were solubilized in TFA-acetonitrile and separated using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) by C8 reverse phase column chromatography. The peptides were eluted with a gradient of TFA/water/acetonitrile. Fractions were dried in a speedvac and subjected to SDS–PAGE (20% gels) and immunoblotting or were tested by ELISA. For peptide sequencing, fractions were separated by electrophoresis, transblotted onto Immobilon P membrane and specific bands were cut out.

Immunoassays

Mimotope ELISA

Mimotope assays with anti-sperm antibodies have been described in detail previously [43]. The basic procedures are those recommended by the manufacturer, Chiron Mimotopes (Clayton, Victoria, Australia). The pin-bound 9mer peptides were incubated overnight at 4°C with either human vasectomy patients' sera diluted 1:200–1:1000 or affinity-purified anti-tNASP human autoantibodies, 200 μl/well. Statistical analysis was performed as described by Pauls et al. [4]. The absorbance value for each individual peptide was transformed into a standard score (Z-score). The mean score expressing the reactivity to a respective serum of all peptides was subtracted from each individual absorbance value and then divided by the s.d. for the particular serum. Results were represented as standard units, called a Z-score. A Z-score of > 2·0 was considered significant. The integrity of the ELISA assay was confirmed by testing in separate analyses the absorbance of the positive control peptide PLAQ (optical density (OD) 450 nm range 0·655–0·883) and the negative control peptide GLAQ (OD 450 nm range 0·156–0·290).

Direct ELISA

Purified recombinant proteins (0·1 μg/well) were immobilized on microtitre plates by using 200 μl/well of Bouin's fixative (15 ml picric acid, 4 ml 37% formaldehyde, 1 ml glacial acetic acid). The plates were centrifuged at 1500 g for 7 min, washed with PBS (0·01 m phosphate pH 7·4, 0·15 m NaCl)/ethanol (1:1 v/v), PBS and PBS–T (PBS + 0·5% Tween), and blocked with PBS–T + 2% non-fat dry milk. After washing, the plates were incubated with human sera, affinity-purified anti-tNASP human autoantibodies or mouse anti-recombinant human tNASP antisera at the indicated dilutions and the reaction was allowed to proceed and develop as already described [43]. For competitive binding inhibition, immobilized recombinant proteins were incubated with antibody in the presence of the respective antigen (20 μg/ml). Following washing, the plates were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated second antibody (Cappel, Organon Teknika, Durham, NC) diluted 1:1500 in PBS + 1% BSA and the reaction was developed as described.

Human sera

The human sera from 21 vasectomy patients used in this study were kindly provided by Drs N. J. Alexander and A. Belker (University of Kentucky). The sera were previously characterized by routine clinical techniques for the presence of anti-sperm agglutinating and immobilizing antibodies. Sera from healthy male individuals and normal female sera were applied as controls in ELISA and immunoblotting. A mouse antiserum produced against recombinant human tNASP (aa 5–787) was used in ELISA as a positive control.

Results

Pattern of anti-tNASP autoreactivity

To map the location of autoimmune epitopes on the primary sequence of human tNASP, cDNAs encoding different segments of the molecule were expressed in E. coli (Fig. 1). The purified recombinant mutants contained beside the complete fusion protein a set of smaller mol. wt fragments that may represent prematurely terminated incomplete translational products and/or proteolytically processed fragments. N-terminal sequencing of a fragment present in the C-terminal fusion protein preparation confirmed this possibility. To examine the distribution of autoepitopes on tNASP, the 6xHis-tagged fusion proteins were employed in ELISA to screen a panel of antibodies from vasectomy patients. Of 21 sera from vasectomy patients with anti-sperm antibodies, 20 (95%) had antibodies to one or more of the tNASP fragments. >Figure 2 shows the reactivity of nine positive sera as assessed by ELISA to seven recombinant fragments spanning the entire protein coding sequence. The reactivity to the different recombinant mutants varied several-fold, with fragments 32–352 and 572–787 exhibiting the highest reactivity (Fig. 2). Immunoblot testing of the nine sera (used in Fig. 2) revealed differential reactivity to the distinct regions, six sera were reactive to the aa 572–787 fragment, two reacted to the aa 32–192 fragment and four to the aa 193–352 fragment. The antibody titres as evaluated by ELISA were not exactly dependent on the presence of Western blot-detectable autoantibody reactivities, thus it may be anticipated that different populations of autoantibodies may be present in vasectomy sera with specificity to conformationally less restrained as well as to conformationally restricted epitopes. The specificity of autoantibody binding to the expressed subfragments aa 32–192, aa 193–352 and aa 572–787 was verified by competitive inhibition with the homologous fusion protein. Furthermore, when sera were tested by immunoblotting to the whole recombinant tNASP (aa 5–787) only one reacted to the largest recombinant protein as opposed to the inability of the majority of sera to recognize the full-length protein in Western blots. This serum (denoted no. 15) was therefore selected for sublibrary screening.

Fig. 2.

Reactivity in ELISA of sera from nine vasectomy patients to seven recombinant fragments of testicular nuclear autoantigenic sperm protein (tNASP).

Mapping of linear autoimmune epitopes

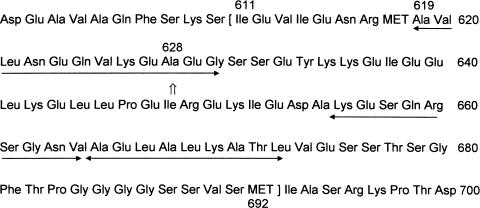

As a result of the foregoing analysis to limit the boundaries of antigenic sites, a tNASP cDNA sublibrary was constructed and screened with the selected human serum no. 15 as a probe. A number of positive, overlapping cDNA clones were identified which all cross-hybridized with each other. By Southern blotting of different restriction fragments encompassing the entire tNASP sequence with one of these clones as a probe designated C1 (100 bp in length), it was found that clone C1 hybridized to the C-terminal restriction fragment (nt 1802–2446) of tNASP cDNA. Using the expressed C-terminal mutant, the ability was shown of the majority of the original 21 human vasectomy sera to recognize autoimmune epitopes in this domain, 95% positive by ELISA, thus indicating a major epitope in this region recognized when denatured and presumably linear. Furthermore, to map the location of autoimmune epitopes within the C-terminal domain of tNASP, serum no. 15 was used on a Western blot of the N- and C-terminal fragments (Fig. 3). As shown in Fig. 3, lane 1, the predominant immunoreactive band corresponded to a protein staining band of mol. wt 26 kD, which is smaller than the complete C-terminal fusion protein (Fig. 3, lane 3). No appreciable reactivity was seen to the N-terminal fragment (Fig. 3, lanes 2 and 4). Normal human male and female sera and a vasectomy serum no. 18 which exhibited no reactivity to tNASP by ELISA were used as controls. No staining of the full-length mutants as well as of smaller subfragments was observed. Microsequencing of the 26-kD band revealed the N-terminal sequence to be AEGS…, which starts at amino acid position number 628 (Fig. 4), indicating that the band was a breakdown product of the expressed C-terminal fragment 572–787. The prevalent recognition of the smaller fragment (mol. wt 26 kD band) compared with the whole expressed protein was observed for all six sera which were positive to the C-terminal in immunoblots. Thus, the pattern of immunoreactivity with the degradation product of the C-terminal fragment is consistent with a better reactivity to the corresponding epitope when it is presented on a smaller mol. wt polypeptide. To narrow the boundary of amino acids contributing to immunogenicity at the C-terminal, the C-terminal recombinant protein (aa 572–787) was cleaved with CNBr and the generated fragments separated by HPLC. The immune reactivity of the fractions was evaluated by ELISA and immunoblotting with vasectomy serum no. 15. The major reactivity was contained in an immunoreactive band of mo. wt 5·8 kD after SDS–PAGE (data not shown). Microsequencing of the 5·8-kD band revealed the N-terminal sequence to be AVLN…, which corresponds to the predicted CNBr fragment aa 619–692 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Western blot analysis of vasectomy serum no. 15 on N-terminal and C-terminal fragments of testicular nuclear autoantigenic sperm protein (tNASP). Lanes 1 and 2, Western blot of lanes 3 and 4 with vasectomy serum no. 15; lanes 3 and 4, protein stain; lanes 1 and 3, C-terminal aa 573–787; lanes 2 and 4, N-terminal aa 5–192.

Fig. 4.

The human testicular nuclear autoantigenic sperm protein (tNASP) amino acid sequence aa 600–700 [32]. The N-terminal sequence of the 26-kD band identified in Fig. 3 starts at Ala, aa 628 (⇑). The N-terminal 12 amino acid sequence of the cyanogen bromide (CNBr) fragment reactive to vasectomy serum no. 15 starts at Ala, aa 619. The synthetic 9mer peptides used in the mimotope analysis start at Ile, aa 611 ([) and continue through Met, aa 692 (]). The two major autoepitopes are indicated by heavy double-headed arrows, Lys-Val, and Ala-Leu.

Mimotope analysis

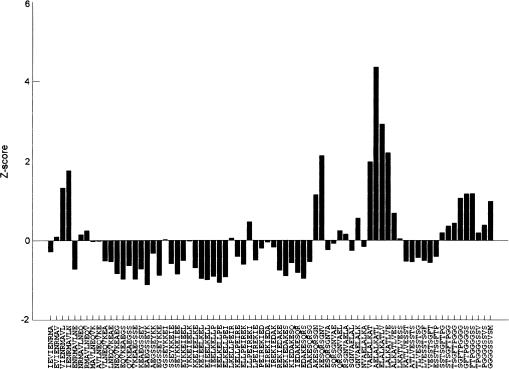

Given the reactivity of autoimmune sera which was delimited to the C-terminal aa 619–692, to analyse more precisely the extent to which the removal of amino acids from the C-terminus might be tolerated without affecting antigenicity, a set of 74 sequentially overlapping, synthetic 9mer peptides representing the sequence from IEV… to …VSM (aa 611–692) was synthesized on polyethylene pins and used in an ELISA format of immunoassay for further analysis. This immunoassay should assess the capacity of the human autoantisera to recognize short linear peptides able to mimic the structural features of sequential epitopes. When serum no. 15, which had been subjected to affinity purification on the recombinant aa 5–787 tNASP, was tested in the mimotope ELISA, it reacted with one highly significant autoimmune epitope, AELALKATL (aa 665–673; Z-score > 4·0, Fig. 5) and a second somewhat less significant epitope, KESQRSGNV (aa 656–664; Z-score > 2·0, Fig. 5). The corresponding mimotope analysis for vasectomy serum no. 18 (control) which did not react with tNASP is shown in Fig. 6. Analysis of the Z-scores of the epitope scans with five additional vasectomy sera revealed that all individual patients' sera reacted with epitopes within the sequence IRE….GGS (aa 648–688). The strongest reactivities (Z-scores > 2) were displayed by peptides corresponding to sequences: IREKIEDAK (aa 648–656; one patient, peptide scan not shown), KESQRSGNV (aa 656–664; four patients), AELALKATL (aa 665–673; four patients), and GFTPGGGGS (aa 680–688; two patients, peptide scan not shown). To determine whether or not the antigenic sites present on the peptides were also accessible on the complete C-terminal fusion protein, a competitive inhibition assay was devised. In this assay anti-tNASP-specific autoantibodies in the vasectomy serum competed between the pin-immobilized peptide and the recombinant protein in liquid phase. As shown in Fig. 7, the binding of the autoantibody to the peptides spanning the sequence VAELALKATLVE (aa 664–675) was appreciably inhibited, suggesting that the epitope AELALKATL is available for immune reaction on the complete C-terminal fusion protein as well as on the immobilized peptide.

Fig. 5.

Reactivity of testicular nuclear autoantigenic sperm protein (tNASP) 9mer peptides, representing the sequence of amino acids 611–692, with affinity-purified human anti-tNASP antibodies (patient no. 15). For sequence AELALKATL, Z-score > 4; for KESQRSGNV, Z-score > 2.

Fig. 6.

Reactivity of testicular nuclear autoantigenic sperm protein (tNASP) 9mer peptides, representing the sequence of amino acids 611–692, with anti-sperm antibody vasectomy serum (patient no. 18) which did not react with tNASP (control).

Fig. 7.

Competitive inhibition assay of anti-testicular nuclear autoantigenic sperm protein (tNASP)-specific autoantibodies (patient no. 19). Autoantibody binding to the pin-immobilized peptides VAELALKATLVE is inhibited by the recombinant protein in liquid phase.

Discussion

This study has demonstrated the major autoantigenic regions in human tNASP and fine specificity of linear autoepitopes targeted by autoantibodies in the sera of vasectomized men. Antibody reactivities against peptides aa 32–352 and aa 572–787 represent the major anti-tNASP specificity. Initial autoepitope analysis was performed by deletion mapping of recombinant proteins expressed in E. coli and screening of a tNASP cDNA sublibrary with a vasectomy patient's serum. The removal of flanking sequences is not deleterious to autoantibody binding sites in these regions, but is not compatible with binding to the midregion aa 353–572, otherwise autoantibodies to this fragment might be infrequently generated. By using an epitope-coding cDNA clone selected from the sublibrary, recombinant proteins expressing various regions of tNASP, and synthetic peptides derived from a 72 amino acid autoantigenic fragment, the sequences of four linear autoimmune epitopes in the C-terminal of tNASP have been defined. The sequence of aa 648–688 is essentially identical in rabbit tNASP [35], human tNASP [38] and sNASP [39]. The heterogeneity in the location of autoimmune epitopes in the C-terminal domain of the molecule as well as in the testis-specific N-terminal region encompassing the histone-binding sites aa 116–127 and aa 211–244 [40] suggests that tNASP itself perpetuates the autoimmune response in vasectomized men.

The epitopes identified in this study appear to be structured primarily by the juxtaposition of hydrophobic and charged amino acids, while aromatic amino acids are underrepresented. The addition of valine (V), a hydrophobic aliphatic residue and glutamic acid (E), to the C-terminal of the peptide AELALKATL did not appreciably affect the antibody binding, but the addition of two serines (S), charged polar residues, and a threonine (T), a charged hydrophobic residue, did severely hinder antibody binding (see Figs 5 and 7). In the peptide KESQRSGNV, the loss of lysine (K), a charged residue, from the N-terminal and the addition of alanine (A), a small hydrophobic residue, to the C-terminal abolished the antibody binding (Fig. 6). In the two other immunodominant epitopes found in this study (peptide scans not shown), the removal of isoleucine (I), a hydrophobic aliphatic residue, from the N-terminal and the addition of glutamic acid (E), a charged residue, to the C-terminal of the peptide IREKIEDAK resulted in marked reduction of autoantibody binding. The addition of two serine (S) residues to the C-terminal end of the glycine motif (GGGG) of the peptide GFTPGGGG, potentiated the binding of autoantibodies. However, with the addition of a C-terminal valine (V) the binding was abolished. The profile of immunoreactivity was consistently reproducible for all sera tested, thus it may be suggested that the intrinsic structural features and conformational constraints of this domain encompassing aa 648–688 mark it for autoantibody recognition. Peptides covering the rest of the sequence IEV…. EDA were essentially non-immunoreactive, as indicated by the negative Z-scores of peptides in this region. Positioned in the secondary structure of tNASP, the four linear epitopes map to α helical coiled-coil regions, extended parts of the protein backbone (β sheets), locally folded parts (β turns) and regions of high flexibility. Structural aspects such as the presence of charge-rich, coiled-coil α helices have been suggested to contribute to the autoantigenic potential of systemic autoantigens, and the preferential processing by the B cells of antigens containing such segments has also been suggested [44]. Although not all immunodominant sites adopt secondary structures, the ability to fold as an α helical structure may be an intrinsic feature that favours an immune response, and such helical structures have been implicated in antigen presentation [45]. Antigenicity of conserved structural motifs has been noted as a general rule for nuclear antigens, even though there is considerable heterogeneity among the epitopes recognized by patient sera in a number of nuclear autoantigens [14,21,46]. However, a more limited distribution of epitopes has been detected for anti-histone antibody responses in lupus patients [47].

The identification of autoepitopes on tNASP has been carried out employing immunoblotting and ELISA assays which favour the detection of linear epitopes on denatured antigens [48]. The ability of autoantibodies in the vasectomy sera to recognize short peptides suggests that the autoantibody response is driven by the antigen after being processed to peptides. The preferential immunodetection by human sera of the cognate epitope when presented on shorter, truncated forms of the recombinant subfragment and/or on breakdown products in Western blots as opposed to lesser or no binding to the longer, complete fusion protein (Fig. 3) argues in favour of this suggestion. In this regard, the autoantibodies in the vasectomy sera behave as anti-peptide antibodies, and this mode of reactivity has some implications for the mechanism of generation of tNASP-specific human autoantibodies to the processed antigen. Anti-peptide antibodies have been shown to bind well to the homologous peptide endowed in most cases with higher than average atomic mobility and flexibility [49–51], yet fail to react or only rarely bind to the longer more ordered parent protein [52]. A similar observation has been reported for autoantibodies to other self proteins such as histones [53], protein D of Sm antigen [54], and topoisomerase I [55].

The existence of a peptide within a larger protein with flanking sequences present may affect antibody recognition by limiting the range of conformations adopted by the peptide. Hence, in the present study, the use of short protein fragments made the heterogeneity of the autoimmune response to tNASP more detectable. Most epitopes need the native conformation of the protein in order to be immunoreactive, and flexible portions of the protein may be expected to have higher than average antigenicity [49]. Some structural motifs of protein architecture may facilitate the cross-reaction of short segments of the protein with protein-specific and conformation-dependent antibodies [56]. On the basis of this view, the mimotope format of immunoassay may be biased to the detection of epitopes situated in extended parts of the protein backbone or in locally folded parts. Indeed, in a competitive inhibition assay, the binding to one of the linear epitopes (AELALKATL) was appreciably inhibited by the C-terminal region recombinant protein, thus confirming the specificity and availability of the corresponding epitope as solvent exposed in the context of the parent fusion protein.

Finally, it should be noted that the use of a peptide to mimic the initial conformation of the cognate sequence in a protein may be useful in a diagnostic strategy depending on its propensity to adopt the appropriate conformation at the epitope location in the protein. Antibodies to one or more of the autoimmune epitopes present in almost all vasectomized men may make them useful as markers for anti-sperm antibodies. Additionally, the potential for cross-reactivity of anti-tNASP autoantibodies following vasectomy with somatic NASP is present and may be of significance in those individuals who mount a strong autoimmune response and/or those who desire to return to fertility.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr I. Lea for the critical reading of the manuscript and many helpful suggestions during the course of this study. This study was supported by NIH/NICHD through cooperative agreement U54HD35041 as part of the SCCPRR.

References

- 1.Tan EM. Antinuclear antibodies: diagnostic markers for autoimmune diseases and probes for cell biology. Adv Immunol. 1989;44:92–152. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60641-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naparstek Y, Plotz PH. The role of autoantibodies in autoimmune disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11:79–104. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.000455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Getzoff ED, Tainer JA, Lerner RA, Geysen HM. The chemistry and mechanism of antibody binding to protein antigens. Adv Immunol. 1988;43:1–98. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60363-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pauls JD, Edworthy SM, Fritzler MJ. Epitope mapping of histone 5 (H5) with systemic lupus erythematosus, procainamide-induced lupus and hydralazine-induced lupus sera. Mol Immunol. 1993;30:709–19. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(93)90142-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodda SJ, Maeji NJ, Tribbick G. Epitope mapping using multipin peptide synthesis. Meth Mol Biol. 1996;66:137–47. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-375-9:137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehra V, Sweetser D, Young RA. Efficient mapping of protein antigenic determinants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:7013–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.18.7013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scott JK, Smith GP. Searching for peptide ligands with an epitope library. Science. 1990;249:386–90. doi: 10.1126/science.1696028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dottavio D. Epitope mapping using phage-displayed peptide libraries. Meth Mol Biol. 1996;66:181–93. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-375-9:181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geysen HM, Meloen RH, Barteling SJ. Use of peptide synthesis to probe viral antigens for epitopes to a resolution of a single amino acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:3998–4002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.13.3998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geysen HM, Rodda SJ, Mason TJ, Tribbick G, Schoofs PJ. Strategies for epitope analysis using peptide synthesis. J Immunol Methods. 1987;102:259–74. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(87)90085-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laver WG, Air GM, Webster RG, Smith-Gill SJ. Epitopes on protein antigens: misconceptions and realities. Cell. 1990;61:553–6. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90464-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rokeach LA, Jarnatipour M, Hoch S. Heterologous expression and epitope mapping of a human small nuclear ribonucleoprotein-associated Sm-B′/B autoantigen. J Immunol. 1990;144:1015–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chou C-H, Reeves WH. Recognition of multiple epitopes in the coiled-coil domain of lamin B by human autoantibodies. Mol Immunol. 1992;29:1055–64. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(92)90037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reeves WH, Pierani A, Chou C-H, Nig T, Nicastri C, Roeder RG, Stroeger ZM. Epitopes of the p70 and p80 (Ku) lupus autoantigens. J Immunol. 1991;146:2678–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barakat S, Briand JP, Abuaf N, Van Regenmortel MHV, Muller S. Mapping of epitopes on U1 snRNP polypeptide A with synthetic peptides and autoimmune sera. Clin Exp Immunol. 1992;86:71–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1991.tb05776.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bunn CC, Mathews MB. Autoreactive epitope defined as the anticodon region of alanine transfer RNA. Science. 1987;238:1116–9. doi: 10.1126/science.2446387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoet RM, DeWeerd P, Klein Gunnewiek J, Koornneef I, Van Venrooij W. Epitope regions on small nuclear RNA recognized by anti-U1RNA-specific autoantibodies. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:1753–62. doi: 10.1172/JCI116049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McNeilage LJ, Macmillan EM, Wittingham SF. Mapping of epitopes on the La (SS-B) autoantigen of primary Sjögren's syndrome: identification of a cross-reactive epitope. J Immunol. 1990;145:3829–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bini P, Chu J-L, Okolo C, Elkon K. Analysis of autoantibodies to recombinant La (SS-B) peptides in systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjögren's syndrome. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:325–33. doi: 10.1172/JCI114441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boire G, Lopez-Longo F-J, Lapointe S, Menard HA. Sera from patients with autoimmune disease recognize conformational determinants on the 60 kDa Ro/SS-A protein. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34:722–30. doi: 10.1002/art.1780340613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saitta M, Arnett FC, Keene JD. 60-kDa Ro protein autoepitopes identified using recombinant polypeptides. J Immunol. 1994;152:4192–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bluthner M, Schafer C, Schneider C, Bautz FA. Identification of major linear epitopes on the sp100 nuclear PBC autoantigen by the gene-fragment phage-display technology. Autoimmunity. 1999;29:33–42. doi: 10.3109/08916939908995970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grogolo B, Mazzetti I, Borzi RM, Hickson ID, Fabbri M, Fasano L, Meliconi R, Faccini A. Mapping of topoisomerase II alpha epitopes recognized by autoantibodies in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;114:339–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00747.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shen GQ, Shoenfeld Y, Peter JB. Anti-DNA, anti-histone, and antinucleosome antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus and drug-induced lupus. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 1998;16:321–34. doi: 10.1007/BF02737642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trussell J, Leveque JA, Koenig JD, et al. The economic value of contraception: a comparison of 15 methods. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:494–503. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.4.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alexander NJ, Anderson DJ. Vasectomy—consequences of autoimmunity to sperm antigens. Fertil Steril. 1979;32:253–60. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)44228-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Linnet L, Hjort T, Fogh-Anderson P. Association between failure to impregnate after vasovasostomy and sperm agglutinins. Lancet. 1981;1:117–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)90708-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flickinger CJ, Harris M, Herr J, Howards SS. Early antibody response following vasectomy is related to fertility after vasovasostomy in glucocorticoid-treated and untreated Lewis rats. J Urol. 1994;151:791–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35089-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tung KSK, Bryson R, Goldberg E, Han LB. Antisperm antibody in vasectomy: studies in human and guinea pig. In: Lepow IH, Crozier R, editors. Vasectomy: immunologic and pathophysiologic effects in animals and man. New York: Academic Press; 1979. pp. 267–84. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tung KSK, Yule TD, Mahi-Brown CA, Listrom MB. Distribution of histopathology and Ia positive cells in actively induced and passively transferred experimental autoimmune orchitis. J Immunol. 1987;138:752–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Samuel T, Kolk AHJ, Rumke P, Van Lis JMJ. Auto-immunity to sperm antigens in vasectomized men. Clin Exp Immunol. 1975;21:65–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Samuel T. Antibodies reacting with salmon and human protamines in sera from infertile men and from vasectomized men and monkeys. Clin Exp Immunol. 1977;30:181–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adourian U, Shampaine EL, Hirshman CA, Fuchs E, Adkinson NF. High-titer protamine-specific IgG antibody associated with anaphylaxis: report of a case and quantitative analysis of antibody in vasectomized men. Anesthesiology. 1993;78:368–72. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199302000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richardson RT, Widgren EE, O'Rand MG. Molecular comparison of two sperm autoantigens. In: Dondero E, Johnson PM, editors. Reproductive immunology. New York: Raven Press; 1993. pp. 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Welch JE, Zimmerman LJ, Joseph DR, O'Rand MG. Characterization of a sperm-specific nuclear autoantigenic protein. I. Complete sequence and homology with the Xenopus protein N1/N2. Biol Reprod. 1990;43:559–68. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod43.4.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Welch JE, O'Rand MG. Characterization of a sperm-specific nuclear autoantigenic protein. II. Expression and localization in the testis. Biol Reprod. 1990;43:569–78. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod43.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee YH, O'Rand MG. Ultrastructural localization of NASP, a nuclear autoantigenic sperm protein, in spermatogenic cells and spermatozoa. Anat Rec. 1993;236:442–8. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092360304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O'Rand MG, Richardson RT, Zimmerman LJ, Widgren EE. Sequence and localization of human NASP. conservation of a Xenopus histone-binding protein. Dev Biol. 1992;154:37–44. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(92)90045-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richardson RT, Batova IN, Zheng L-X, Whitfield M, Marzluff WF, O'Rand MG. Characterization of the histone-binding protein NASP, as a cell cycle regulated somatic protein. submitted. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Batova IN, O'Rand MG. Histone-binding domains in a human nuclear autoantigenic sperm protein. Biol Reprod. 1996;54:1238–44. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod54.6.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanger FS, Nicklen S, Coulson AR. DNA sequencing with chain terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O'Rand MG, Widgren EE. Identification of sperm antigen targets for immunocontraception: B-cell epitope analysis of Sp17. Reprod Fertil Dev. 1994;6:289–96. doi: 10.1071/rd9940289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dohlman JG, Lupas A, Carson M. Long charge-rich alpha-helices in systemic autoantigens. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;195:686–96. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Estaquier J, Boutillon C, Grass-Masse H, Ameisen A-C, Capron A, Tartar A, Auriault C. Comprehensive delineation of antigenic and immunogenic properties of peptides derived from the nef HIV-1 regulatory protein. Vaccine. 1993;11:1083–92. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(93)90066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guldner HH, Netter HJ, Szostecki C, LaKomek HJ, Will M. Epitope mapping with a recombinant human 68 kDa (U1) ribonuclearprotein antigen reveals heterogeneous autoantibody profiles in human autoimmune sera. J Immunol. 1988;141:469–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rubin RL, Waga S. Antihistone antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 1987;14:118–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.St Clair EW, Pisetsky DS, Reich CF, Chambers JC, Keene JD. Quantitative immunoassay of anti-La antibodies using purified recombinant La antigen. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:506–14. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tainer JA, Getzoff ED, Alexander H, Houghten RA, Olson AJ, Lerner RA. The reactivity of anti-peptide antibodies is a function of the atomic mobility of sites in the protein. Nature (London) 1984;312:127–34. doi: 10.1038/312127a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tainer J, Getzoff E, Paterson Y, Olson A, Lerner RA. The atomic mobility component of protein antigenicity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1985;3:501–35. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.03.040185.002441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaiser ET, Kezdy FJ. Secondary structures of proteins and peptides in amphiphilic environments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:1137–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.4.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Geysen HM. Antigen–antibody interactions at the molecular level: adventures in peptide synthesis. Immunol Today. 1985;6:364–9. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(85)90096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tuaillon N, Muller S, Pasquali JL, Bordigoni P, Youinou P, Van Regenmortel MHV. Antibodies from patients with rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile chronic arthritis analyzed with core histone synthetic peptides. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1990;91:297–305. doi: 10.1159/000235131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Barakat S, Briand J-P, Weber J-C, Van Regenmortel MHV, Muller S. Recognition of synthetic peptides of Sm-D autoantigen by lupus sera. Clin Exp Immunol. 1990;81:256–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1990.tb03327.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McNeilage LJ, Youngchaiyud U, Whittingham S. Racial differences in antinuclear antibody patterns and clinical manifestations of scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32:54–60. doi: 10.1002/anr.1780320109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Van Regenmortel MHV. Structural and functional approaches to the study of protein antigenicity. Immunol Today. 1989;10:266–72. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(89)90140-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]