Abstract

Hepatic parenchymal cells respond in many different ways to acute-phase cytokines. Some responses may protect against damage by liver-derived inflammatory mediators. Previous investigations have shown that cytokines cause increased secretion by hepatoma cells of soluble complement regulatory proteins, perhaps providing protection from complement attack. More important to cell protection are the membrane complement regulators. Here we examine, using flow cytometry and Northern blotting, the effects of different cytokines, singly or in combination, on expression of membrane-bound complement regulators by a hepatoma cell line. The combination of tumour necrosis factor-alpha, IL-1β, and IL-6 caused increased expression of CD55 (three-fold) and CD59 (two-fold) and decreased expression of CD46 at day 3 post-exposure. Interferon-gamma reduced expression of CD59 and strongly antagonized the up-regulatory effects on CD59 mediated by the other cytokines. Complement attack on antibody-sensitized hepatoma cells following a 3-day incubation with the optimum combination of acute-phase cytokines revealed increased resistance to complement-mediated lysis and decreased C3b deposition. During the acute-phase response there is an increased hepatic synthesis of the majority of complement effector proteins. Simultaneous up-regulation of expression of CD55 and CD59 may serve to protect hepatocytes from high local concentrations of complement generated during the acute-phase response.

Keywords: hepatoma, acute phase, complement regulators, cytokines

Introduction

The hepatocyte is the primary site of synthesis for the majority of the complement (C) components [1]. As a consequence, the local concentration of C components in the vicinity of hepatocytes is probably much higher than that measured in plasma. During the acute-phase (AP) response, the biosynthesis of these C components is increased several-fold by the action on hepatocytes of AP response-associated cytokines, IL-1 and IL-6 and tumour necrosis factor (TNF) [2–4]. One consequence of this is to increase further the local concentration of C components in the liver. Therefore, during the AP response, hepatocytes will be exposed to very high local concentrations of C components that could pose the threat of C-mediated damage to the cells [5–10].

Cells express soluble and membrane-bound C regulators to protect against C damage [11]. Of the secreted proteins, C4b-binding protein (C4bp) and factor H (fH) act to inhibit during the activation stages while S-protein and clusterin act in the terminal pathway. Of the membrane-associated proteins, decay-accelerating factor (DAF; CD55) and membrane cofactor protein (MCP; CD46) act in the activation stages and CD59 regulates the terminal pathway. These latter proteins are critical for protection from C damage, as is evident from numerous studies where membrane C regulators have been blocked with specific antibodies. Up-regulation of membrane C regulators has been implicated as a survival strategy in numerous human tumours [12–14].

Despite their key role in C biosynthesis, expression of C regulators by hepatocytes has not been studied in detail. Because of the difficulties in maintaining primary hepatocytes in culture, hepatoma-derived cell lines have been widely used as in vitro models in studies of hepatocyte functions, including C biosynthesis [15]. We have previously shown that expression of the α- and β-chains of the soluble C regulator C4bp is up-regulated upon exposure of hepatoma cells to the AP cytokines IL-6/IL-1β/interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), but down-regulated by TNF-α [16]. In contrast, expression of the soluble C regulator factor H was not altered by exposure of hepatoma cells to IL-6/IL-1β/TNF-α, but was up-regulated by IFN-γ [17]. Hepatocyte/hepatoma expression of the membrane-bound C regulators, CD55, CD46 and CD59, has not been studied in detail. One report identified message for each of the membrane C regulators in the HepG2 cell line [18], while a study of the role of C in acute hepatitis found that only CD46 was present on hepatocytes in vivo [19].

We set out to confirm the expression of membrane C regulators on hepatocyte-derived cell lines and to analyse the effects of cytokines associated with the acute phase (IL-6/IL-1β/TNF-α) and with chronic inflammation (IFN-γ) on expression. The functional consequences of cytokine-induced changes in expression of C regulators were assessed using assays of C3b deposition and cell lysis. The data demonstrate that AP cytokines increase the expression of membrane C regulator on hepatocyte-derived cells and increase cell resistance to C damage.

Materials and methods

Cells

Hepatoma cell lines Hep3B and HepG2 were obtained from the European Collection of Animal Cell Cultures (ECACC; Salisbury, UK) and propagated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), supplemented with glutamine, penicillin and streptomycin (Life Technologies, Paisley, UK). Hepatoma cell lines were used for all experiments, as we were unable to obtain primary human hepatocytes from local or commercial sources.

Cytokines

Cytokines were purchased from Boehringer (Mannheim, Germany) and were added to the cell medium at the following concentrations: IL-6 500 U/ml, IL-1β 5 ng/ml, TNF-α 5 ng/ml, IFN-γ 200 U/ml. Cell supernatants were changed daily. Preliminary titration analyses were performed for individual cytokines on complement regulator expression and a minimal response to different concentrations was found; therefore the concentrations used were chosen to reflect physiological levels in vivo.

Flow cytometry

Cells (5 × 105) were seeded into small Petri dishes and, following incubation with cytokines, were washed twice with PBS, then disaggregated with flow cytometry buffer (FCB; PBS containing 15 mm EDTA, 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 15 mm NaN3, pH 7·4). The cells were resuspended at a concentration of 106/ml. Cells (100 μl; 105) were incubated with 5 μg of specific primary antibody for 30 min on ice, and the unbound antibody removed by three washes with FCB. The cells were then incubated with 1:100 dilution of the PE-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Dako Ltd, Ely, UK), washed three more times with FCB and analysed on a Becton Dickinson FACScalibur (Oxford, UK). All measurements were made in duplicate and each experiment was replicated two to three times; all results were combined and statistically analysed. Statistical analysis consisted of anova with post hoc analysis of significant results using Fischer's least significant difference test. Primary antibodies included OX23 (isotype-matched control; ECACC), 1H4 (CD55; Dr W. Rosse, Duke University, NC), MBC1 (CD55; this laboratory), E4.3 (CD46; B. Loveland, Austin Institute, Melbourne, Australia), M177 (CD46; Serotec Ltd), MEM43 (CD59; Dr V. Horejsi, Institute of Molecular Genetics, Prague, Czech Republic), B229 (CD59; IBGRL, Elstree, UK), W6/32 (HLA class I; ECACC), OKT9 (CD71; Dr W. Jefferies, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada) and C3/30 (C3b/iC3b; Dr P. Taylor, Novartis, Horsham, UK).

Calcein release

Hepatoma cells were grown in 24-well plates (104 cells/well) and cytokines added in the combinations indicated for the length of time specified in the results. Prior to C attack, cells were loaded with 2 μg/ml of calcein AM (Molecular Probes, Portland, OR) for 1 h at 37°C. Where indicated, cells were additionally sensitized with 10% rabbit polyclonal anti-U937 antiserum (raised in this laboratory against CD59-negative U937 line) diluted in serum-free DMEM. This U937 cell line was used to generate sensitizing antibodies, as it is deficient in CD59, and purified soluble CD55 was added to the antiserum to remove the reactivity with CD55. The resultant antiserum has a broad range of cross-reactivity with other human cell lines, including the hepatoma lines used here. Following sensitization, cells were then incubated for 1 h at 37°C with 20% normal human serum diluted in veronal buffered saline (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK). Released calcein was collected and cell-associated calcein was then released with 0·1% Triton X-100. Measurements of calcein were made using the Denley Wellfluor fluorimeter (Life Sciences Int. Ltd, Basingstoke, UK) set at excitation wavelength of 485 nm and emission wavelength of 530 nm. Percent lysis was calculated for each well, and all conditions were performed in triplicate.

C3 deposition

Hepatoma cells were set out and incubated with cytokines as described above, then sensitized and incubated with 20% human serum in veronal-buffered saline for 10 min, stained with the C3/30 antibody and subjected to flow cytometry. The background was assessed by using an isotype-matched control antibody in place of C3/30 in identical cultures. Levels of sensitizing antibody binding were also assessed by flow cytometry for each condition using PE-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin antiserum (Sigma Aldrich Chemical Co., Poole, UK). Where preliminary experiments indicated that incubation of cells with cytokines altered sensitizing antibody binding, the input levels of sensitizing antibody were adjusted so that staining with anti-rabbit antibody assessed by FACS analysis indicated roughly equal binding.

Northern blot analysis

Steady state levels of CD55, CD46 and CD59 mRNAs were determined for 5 × 105 hepatoma cells grown in 35-mm2 Petri dishes and incubated for 1–4 days with no added cytokines or with a combination of IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α. Medium was changed daily and total RNA was harvested for each condition at 24-h intervals using a guanidium isothiocyanate method [20]. Total RNA (10 μg) was separated by electrophoresis on a 1·3% formaldehyde-agarose gel and transferred onto nylon membranes. The nylon membranes were then sequentially probed with 32P-labelled DNA probes made from CD55, CD59, and CD46 cDNAs, each containing the entire coding sequence [21]. The levels of human CD55, CD59 and CD46 mRNAs were quantified by exposure of the Northern blot membranes to photoactivated storage phosphorimaging plates to obtain autoradiographic images which were analysed by densitometry (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). All samples were also probed for GAPDH mRNA and results were normalized for loading by calculating the ratios relative to GAPDH signal. Data were collected for four (CD59 and CD46) or two (CD55) experiments.

Results

Expression at the mRNA level of CD46, CD55, and CD59 and effect of AP cytokines

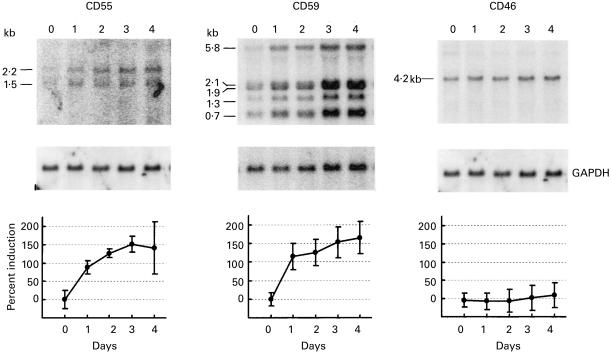

Expression in hepatoma cells of mRNA encoding the membrane C regulators was assessed by Northern blot analysis. Cells were examined unstimulated and at various intervals following exposure to a combination of IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α. This combination of cytokines was chosen because they are specific to the AP response and are released by infiltrating inflammatory cells; the concentrations were chosen to mimic those reported in vivo during the AP response [2,3,22,23]. Total RNA was collected from Hep3B cells, separated on a denaturing agarose gel, and probed for CD55, CD59, CD46 and GAPDH (Fig. 1). Cells prior to exposure to cytokines expressed mRNA for each of the regulators. Upon exposure to cytokines, mRNA levels for CD55 and CD59 were doubled by day 1 and increased 2·5-fold compared with basal levels by day 3. For CD46, no change in mRNA expression was detected at any time point.

Fig. 1.

Autoradiographs showing steady state mRNA levels for CD55, CD59, CD46 and GAPDH in samples collected from Hep3B cells at 24-h intervals following exposure to IL-6, IL-1β, and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). The major mRNA species are identified to the left of each blot and normalized densitometry values are shown at bottom. Data represent the mean value ± s.d. (expressed relative to unstimulated cells taken as 0%) for four (CD59/CD46) or two (CD55) experiments.

Expression at the protein level of CD46, CD55, and CD59 and effect of AP cytokines

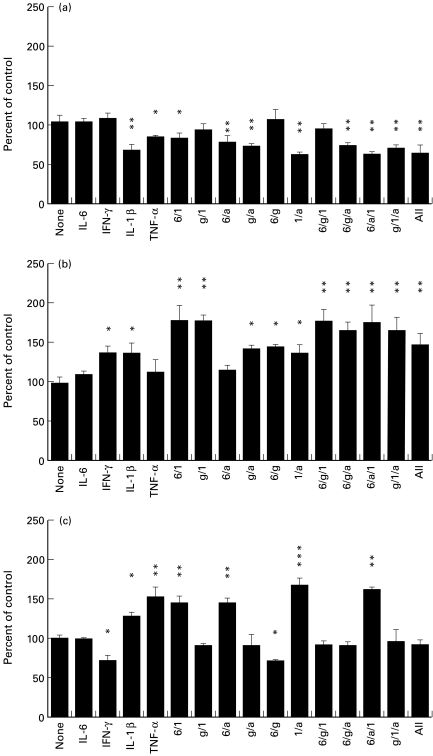

To assess the effects of the cytokines on expression by hepatoma cells of membrane C regulators at the protein level, cells were incubated with cytokines, stained with specific antibodies and analysed by flow cytometry (Fig. 2). In vivo, the levels of IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α will all be increased together during the AP response. However, we wished to examine if one particular cytokine was more important for the alteration in C regulator expression than the others. In order to examine this, Hep3B cells were incubated for 48 h with individual AP response cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α) alone or in various combinations. The effects of a cytokine associated with chronic inflammation (IFN-γ) were also examined. Each of the three C regulators was expressed on unstimulated cells, CD59 at high level (mean cellular fluorescence (MCF) of 1188 against a background MCF of 4·1) and CD55 and CD46 at lower levels (MCF of 77·7 for CD55, MCF of 293·5 for CD46) as assessed by flow cytometry using specific MoAbs. No combination of cytokines caused increased expression of CD46; however, IL-1β and TNF-α both significantly decreased CD46 expression and acted in combination to further decrease expression (Fig. 2a). Cytokine exposure caused much greater changes in CD55 expression (Fig. 2b). Incubation of Hep3B cells with either IFN-γ or IL-1β increased the expression of CD55 by 40%, and together these cytokines increased expression by 78% compared with controls. Interestingly, although incubation with IL-6 alone did not increase the expression of CD55, co-incubation of IL-6 with IL-1β increased expression of CD55 to a level similar to that induced by IFN-γ and IL-1β together (Fig. 2b). IL-6 had no such synergistic effect on CD55 expression when combined with IFN-γ. Incubation of Hep3B cells with either IL-1β or TNF-α also significantly increased the expression of CD59, and a combination of these two cytokines further enhanced expression (Fig. 2c). IL-6 had no effect on the expression of CD59 and IFN-γ was found to decrease the expression of CD59 by 30%. When IFN-γ was used in combination with any of the up-regulating cytokines, the down-regulating effects of IFN-γ were predominant (Fig. 2c). The data from these protein expression studies support the information obtained at the mRNA level in that the combination of IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α shown to cause a large increase in expression of mRNA for CD55 and CD59 (Fig. 1), also caused a large increase in expression of CD55 and CD59 at the protein level (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Flow cytometric analysis of CD46 (a), CD55 (b), and CD59 (c) expression following a 48-h incubation of Hep3B cells with cytokines. Data graphed represent the mean and s.d. of four measurements obtained from two separate experiments (each point measured in duplicate per experiment). Hep3B cells were incubated with 200 U/ml of IFN-γ (g), 500 U/ml IL-6 (6), 5 ng/ml tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) (a), or 5 ng/ml IL-1β (b), alone or in combination. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01; ***P < 0·001.

Time course of changes in membrane C regulator protein expression induced by cytokine exposure

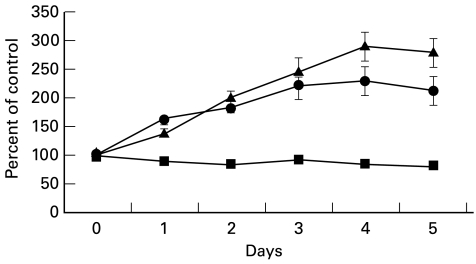

Levels of mRNA for the C regulators CD55 and CD59 increased relatively slowly upon exposure of cells to cytokines (Fig. 1). We therefore wished, for comparison, to determine the rate at which the cell surface expression of the C regulators increased upon exposure to the AP response cytokines. Hepatoma cells were examined by flow cytometry, unstimulated and at various intervals following exposure to a combination of IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α (Fig. 3). Expression of CD46, CD55 and CD59 by Hep3B cells at intervals after exposure to cytokines is shown relative to the expression on unstimulated cells (100%). Expression of CD46 fell slowly over the course of the experiment, resulting in a 20% decrease (P < 0·05 for days 2, 3 and 5) compared with cells at day 0 following 5 days of cytokine exposure. Expression of CD55 was 140% at day 1 (P < 0·05) and continued to increase steadily over the first 4 days of continuous cytokine exposure, reaching 280% at day 4 (P < 0·001); the increase was significant at each time point. Expression of CD59 was 165% on day 1 (P < 0·05) and thereafter expression increased slowly to 220% at day 4 (P < 0·001); the increase was significant at each time point.

Fig. 3.

Time course of alterations in CD46 (▪), CD55 (▴), and CD59 (•) expression following incubation with IL-6, IL-1β, and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), as assessed by flow cytometry on Hep3B. Cells were all incubated for 5, 4, 3, 2, or 1 day with cytokines and compared with untreated cells (day 0); measurements for all conditions were obtained on the same day. One of two experiments shown, mean and s.d. of data collected in triplicate are shown.

Functional protection of hepatoma cells following incubation with AP cytokines

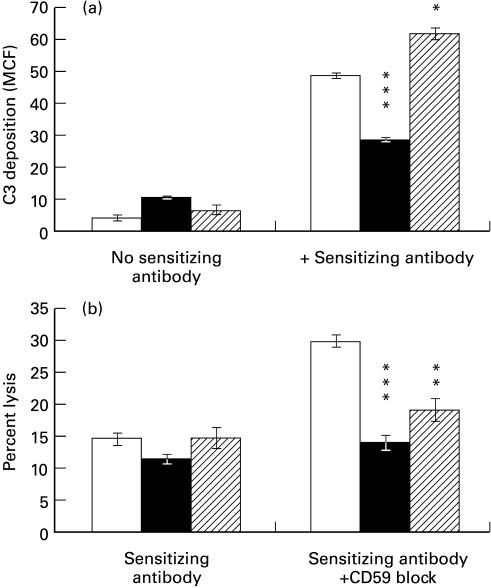

To assess whether the alterations in C regulators had a functional role, Hep3B cells were incubated with either IL-6/IL-1β/TNF-α (up-regulates CD55 and CD59, down-regulates CD46) or IFN-γ (up-regulates CD55, down-regulates CD59) and resistance to C attack compared with untreated cells Fig. 4). The amount of cell-bound sensitizing antibody, as assessed by flow cytometry, was found to be increased by IFN-γ. To compensate for this and eliminate differences in C activation, the amount of input sensitizing antibody was adjusted to obtain equal amounts of cell-bound antibody across all conditions. C3 deposition on sensitized cells was assessed by flow cytometry using anti-C3b/iC3b MoAb following a 10-min incubation with 20% normal human serum (Fig. 4a). Since the anti-C3 MoAb used (C3/30) recognizes a neo-epitope on C3b and iC3b and is not reactive with native C3, we were able to measure C3 deposited on the cell via activation without interference from native C3 associated with or produced by the cell [24]. A 41% reduction in C3 deposition was seen on cells incubated with IL-6/IL-1β/TNF-α (P < 0·001) and a 27% increase in C3 deposition on cells incubated with IFN-γ (P < 0·05).

Fig. 4.

Susceptibility to C attack of Hep3B cells treated with IL-6/IL-1β/tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) (▪) or IFN-γ (hatched) was compared with untreated cells (□). Protection from both C3 deposition following a 10-min incubation with 20% human serum (a) and calcein AM release from cells following a 1-h incubation with 20% human serum (b) are shown. Where indicated, cells were presensitized with a rabbit polyclonal anti-U937 antiserum (which was free of anti-CD59 and anti-CD55 reactivity) or CD59 activity was blocked by preincubation of the cells with 10 μg/ml of the monoclonal anti-CD59, BRIC229. All measurements were made in triplicate and mean and s.d. are shown.

Lytic susceptibility was assessed by measuring calcein release following C attack on sensitized cells. The lysis of untreated Hep3B cells was low and the effects on lysis of incubation with cytokines could not be adequately assessed (Fig. 4b). However, when CD59 activity was blocked by BRIC229, it was apparent that cells incubated with IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α were much more resistant to C-mediated lysis. It is interesting to note that although the levels of C3 deposition on Hep3B cells incubated with IFN-γ were significantly increased, these cells were more resistant to C-mediated lysis following blocking of CD59 than the control cells (Fig. 4). The mechanism by which IFN-γ causes increased resistance to C membrane attack independent of CD59 is unknown.

Discussion

The AP response is characterized by marked changes in the synthesis and secretion of specific proteins by hepatocytes in response to a mixture of acute phase-specific cytokines released by activated phagocytes at sites of injury or inflammation. The majority of the proteins up-regulated during the AP response play roles in immune defence or in the resolution of tissue damage. Hepatocytes are the primary site of synthesis for the majority of the components of C, and synthesis and secretion of these C proteins is also increased during the AP response ([5–9], reviewed in [10]). Therefore, during the acute phase, the local concentration of C components in the local milieu of hepatocytes will be substantially elevated, placing the cells at risk of damage. In order to avoid the threat of damage by high local concentration of C components we speculated that hepatocytes might up-regulate expression of membrane C regulators. The suggestion that hepatocytes might be intrinsically resistant to C damage is supported by recent evidence from a rat model of TNF-induced lethal hepatitis, in which severe liver cell toxicity was accompanied by dramatic consumption of the circulating C components and abundant activation of C in the liver [25]. Depletion of C in this model had no effect on the course of hepatocyte damage, suggesting that hepatocytes were resistant to killing by C.

Expression of membrane C regulators by hepatocyte-derived cells has not been clearly demonstrated and the effects of AP response cytokines on expression has not been examined. The purpose of this study was to examine formally whether hepatocyte-derived cells express the membrane C regulators CD46, CD55 and CD59 and whether cytokines associated with the AP response modulate their expression. Because we were unable to obtain primary hepatocytes, we chose a well-characterized hepatoma cell line, Hep3B, and examined the effects of cytokines implicated in the AP response on expression of C regulators by the cells. A second hepatoma cell line, HepG2, was also examined and gave broadly similar results, but we chose to present results from Hep3B because we have previously found in studies of effects of AP response cytokines on expression of the fluid-phase C regulatory protein, C4bp, that the response to AP cytokines in the latter cell more closely mirrors changes observed in vivo [16,26,27].

We found, both at the mRNA and protein level, expression of each of the membrane C regulators by the hepatoma line Hep3b. Expression in HepG2 was also examined and all three of the membrane C regulators were present at similar expression levels; these data are not included for the sake of clarity. Unstimulated cells expressed each regulator on 100% of the cells. We then tested the effects of cytokines implicated in the AP response or chronic inflammation on expression of the C regulators. The combination of IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α, characteristic of the AP response in vivo, caused a 2·5-fold increase in mRNA for CD55 and CD59 in Hep3B cells within 2–3 days of exposure, but did not alter CD46 mRNA levels. Expression at the protein level correlated with the mRNA result, in that this cytokine combination increased surface expression of CD55 by two to three-fold and CD59 expression by 1·5–2-fold by day 3, but did not significantly alter CD46 expression. Incubation of Hep3B cells with IFN-γ, a cytokine associated with a chronic inflammatory response, down-regulated the expression of CD59. We measured the response of the HepG2 cell line to AP response cytokines in parallel, and always observed findings similar to those in Hep3B cells. The induction of C regulator mRNA continued to increase up to 3 days and protein expression also peaked at day 3. This prolonged time course of induction was surprising, in that others have found maximum induction of C regulator mRNAs to occur within the first day in response to cytokines in other cell types [28,29]. However, a similar requirement for prolonged stimulation with cytokines to increase CD55 expression has been reported for human lung carcinoma cell lines [12]. Our findings are also in agreement with the effects of the AP response in patients: for example, no increase in the serum levels of C4bp are seen in the first 24 h, but are instead observed over a 3–9-day period post-surgery [26].

The effects of IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, and IFN-γ on the expression of CD46, CD55, and CD59 have been investigated on many different cell types. These include cells of human intestinal epithelial, vascular endothelial, keratinocytic, monocytic and fibroblastic origins [28–39]. However, no consistent pattern of response to cytokines has been observed. For some cells, such as keratinocytes or uveal melanocytes, these cytokines have no effect on the expression of CD46, CD55 or CD59 [30,36]. For other cell lines, such as the colonic adenocarcinoma cell line HT29, CD55 expression increased upon exposure to AP response cytokines, but not IFN-γ, and CD46 expression was increased following addition of IL-1β [27,28,31,39]. DAF expression was also found to increase on cells derived from lung carcinomas or primary endothelial cells following incubation with TNF-α or IFN-γ [37,38]. Gasque et al. [40] found an increase in CD59 on oligodendroglioma cells following incubation with IFN-γ. Enhanced expression of C regulators on cells derived from tumours has been postulated as a survival mechanism, and this may explain some of these seemingly contradictory findings [12–14]. It is known that hepatocytes express a unique combination of transcriptional factors which are responsible for the hepatocyte differentiation and gene expression profile [41]. These factors give hepatocytes a unique mode of response to cytokines, which is the basis of the AP response. To test the hepatocyte specificity of the AP response cytokine induction of C regulators, we have exposed unrelated cell lines to these cytokines and see little or no alteration in expression (data not included).

In order for any functional relevance to be attributed to the observed increases in membrane C regulators, it was essential that assays of C susceptibility were performed. These have rarely been done in previous studies. Here we show that cytokine-induced up-regulation of expression of DAF reduces C3b deposition and lytic susceptibility of the hepatoma cell lines. We were unable directly to assess the protective role of increased expression of CD59 because hepatoma cells, even without cytokine treatment, were resistant to C lysis. Of note, treatment with IFN-γ reduced expression of DAF with resultant increased C3b deposition, but rendered hepatoma cells resistant to C lysis even after neutralization of CD59. The mechanism of this surprising resistance to membrane attack is under investigation.

In conclusion, our data demonstrate that AP response cytokines, but not cytokines implicated in chronic inflammation, cause increased expression of two membrane C regulators, CD55 and CD59, on hepatoma lines. Increased C regulator expression caused decreased C3-fragment deposition and increased resistance to C lysis of hepatoma cells following exposure to AP response cytokines. We propose that this increased expression of membrane C regulators might be of functional relevance to homeostasis in the liver during the AP response, protecting against damage by the high local concentrations of C in the liver parenchyma and subverting the threat to hepatocyte integrity.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by The Wellcome Trust and by the Acciones Integrades grant from The British Council. Additional support was obtained from the Comision Interministerial de Ciencia y Tecnologia (SAF99-0013).

References

- 1.Colten HR. Biosynthesis of complement. Adv Immunol. 1976;22:67–118. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60548-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suffredini AF, Fantuzzi F, Badolato R, Oppenheim JJ, O'Grady NP. New insights into the biology of the acute phase response. J Clin Immunol. 1999;19:203–14. doi: 10.1023/a:1020563913045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramadori G, Christ B. Cytokines and the hepatic acute-phase response. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19:141–55. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumann H, Gauldie J. The acute phase response. Immunol Today. 1994;15:74–80. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whaley K, Schwaeble W. Complement and complement deficiencies. Semin Liver Dis. 1997;17:297–310. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falus A, Rokita H, Walcz E, Brozik M, Hidvegi T, Meretey K. Hormonal regulation of complement biosynthesis in human cell lines—II. Upregulation of the biosynthesis of complement components C3, factor B and C1 inhibitor by IL-6 and IL-1 in human hepatoma cell line. Mol Immunol. 1990;27:197–201. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(90)90115-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Platel D, Bernard A, Mack G, Guiguet M. Interleukin 6 upregulates TNFα-dependent C3-stimulating activity through enhancement of TNFα specific binding on rat liver cells. Cytokine. 1996;8:895–9. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1996.0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perissutti S, Tedesco F. Effect of cytokines on the secretion of the fifth and eighth complement components by HepG2 cells. Int J Clin Lab Res. 1994;24:45–48. doi: 10.1007/BF02592409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scheurer B, Rittner C, Schneider PM. Expression of the human complement C8 subunits is independently regulated by interleukin 1 beta, interleukin 6, and interferon gamma. Immunopharmacology. 1997;38:167–75. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(97)00077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Volanakis JE. Transcriptional regulation of complement genes. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:277–305. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.001425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris CL, Morgan BP. Complement regulatory proteins. London: Academic Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Varsano S, Rashkovsky L, Shapiro H, Ophir D, Mark-Bentankur T. Human lung cancer cell lines express cell membrane complement inhibitory proteins and are extremely resistant to complement-mediated lysis; a comparison with normal human respiratory epithelium in vitro, and an insight into mechanism(s) of resistance. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;113:173–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00581.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thorsteinsson L, O'Dowd GM, Harrington PM, Johnson PM. The complement regulatory proteins CD46 and CD59, but not CD55, are highly expressed by glandular epithelium of human breast and colorectal tumour tissues. APMIS. 1998;106:869–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1998.tb00233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niehans GA, Cherwitz DL, Staley NA, Knapp DJ, Dalmasso AP. Human carcinomas variably express the complement inhibitory proteins CD46 (membrane cofactor protein), CD55 (decay-accelerating factor), and CD59 (protectin) Am J Pathol. 1996;149:129–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morris KM, Aden DP, Knowles BB, Colten HR. Complement biosynthesis by the human hepatoma-derived cell line HepG2. J Clin Invest. 1982;70:906–13. doi: 10.1172/JCI110687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Criado Garcia O, Sanchez-Corral P, Rodriguez de Cordoba S. Isoforms of human C4b-binding protein. II. Differential modulation of the C4BPA and C4BPB genes by acute phase cytokines. J Immunol. 1995;155:4037–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams SA, Vik DP. Characterization of the 5′ flanking region of the human complement factor H gene. Scand J Immunol. 1997;45:7–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1997.d01-364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang C, Jones JL, Barnum SR. Expression of decay-accelerating factor (CD55), membrane cofactor protein (CD46) and CD59 in the human astroglioma cell line, D54-MG, and primary rat astrocytes. J Neuroimmunol. 1993;47:123–32. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(93)90022-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pham BNJF, Mosnier F, Durand JY, et al. Immunostaining for membrane attack complex of complement is related to cell necrosis in fulminant and acute hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:495–504. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–9. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spiller OB, Borysiewicz LK, Morgan BP. Development of a model for cytomegalovirus infection of oligodendrocytes. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:3349–56. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-12-3349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boutten A, Dehoux M, Deschenes M, Rouzeau JD, Bories PN, Durand G. Alpha 1-acid glycoprotein potentiates lipopolysaccharide-induced secretion of interleukin-1 beta, interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha by human monocytes and alveolar and peritoneal macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:2687–95. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830221032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xing Z, Jordana M, Kirpalani H, Driscoll KE, Schall TJ, Gauldie J. Cytokine response by neutrophils and macrophages in vivo: endotoxin induces TNFα, MIP-2, IL-1β, and IL-6 but not RANTES or TGFβ1 mRNA expression in acute lung inflammation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1994;10:148–53. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.10.2.8110470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kemp PA, Spragg JH, Brown JC, Morgan BP, Gunn CA, Taylor PW. Immunohistochemical determination of complement activation in joint tissues of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis using neoantigen-specific monoclonal antibodies. J Clin Lab Immunol. 1992;37:147–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Libert C, Wielockx B, Grijalba B, Van Molle W, Kremmer E, Colten HR, Fiers W, Brouckaert P. The role of complement activation in tumour necrosis factor-induced lethal hepatitis. Cytokine. 1999;11:617–25. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1998.0462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Criado-Garcia O, Gonzalez-Rubio C, Lopez-Trascasa M, Pascual-Salcedo D, Munuera L, Rodriguez de Cordoba S. Modulation of C4b-binding protein isoforms during the acute phase response caused by orthopedic surgery. Haemostasis. 1997;27:25–34. doi: 10.1159/000217430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanchez-Corral P, Criado-Garcia O, Rodriguez de Cordoba S. Isoforms of human C4b-binding protein. I. Molecular basis for the C4BP isoform pattern and its variations in human plasma. J Immunol. 1995;155:4030–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andoh A, Fujiyama Y, Sumiyoshi K, Sakumoto H, Bamba T. Interleukin-4 acts as an inducer of decay-accelerating factor gene expression in human intestinal epithelial cells. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:911–8. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(96)70058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andoh A, Fujiyama Y, Sumiyoshi K, Sakumoto H, Okabe H, Bamba T. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha up-regulates decay-accelerating factor gene expression in human intestinal epithelial cells. Immunology. 1997;90:358–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.1997.00358.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pasch MC, Bos JD, Daha MR, Asghar SS. Transforming growth factor-beta isoforms regulate the surface expression of membrane cofactor protein (CD46) and CD59 on human keratinocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:100–8. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199901)29:01<100::AID-IMMU100>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nasu J, Mizuno M, Uesu T, et al. Cytokine-stimulated release of decay-accelerating factor (DAF; CD55) from HT-29 human intestinal epithelial cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;113:379–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00660.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bjorge L, Jensen TS, Matre R. Characterisation of the complement-regulatory proteins decay-accelerating factor (DAF, CD55) and membrane cofactor protein (MCP, CD46) on a human colonic adenocarcinoma cell line. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1996;42:185–92. doi: 10.1007/s002620050269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bryant RW, Granzow CA, Siegel MI, Egan RW, Billah MM. Wheat germ agglutinin and other selected lectins increase synthesis of decay-accelerating factor in human endothelial cells. J Immunol. 1991;147:1856–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lappin DF, Guc D, Hill A, McShane T, Whaley K. Effect of interferon-gamma on complement gene expression in different cell types. Biochem J. 1992;281:437–42. doi: 10.1042/bj2810437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moutabarrik A, Nakanishi I, Namiki M, et al. Cytokine-mediated regulation of the surface expression of complement regulatory proteins, CD46 (MCP), CD55 (DAF), and CD59 on human vascular endothelial cells. Lymphokine Cytokine Res. 1993;12:167–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blom DJ, Goslings WR, De Waard-Siebinga I, Luyten GP, Claas FH, Gorter A, Jager JM. Lack of effect of different cytokines on expression of membrane-bound regulators of complement activity on human uveal melanocyte cells. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1997;17:695–700. doi: 10.1089/jir.1997.17.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Varsano S, Rashkovsky L, Shapiro H, Radnay J. Cytokines modulate expression of cell-membrane complement inhibitory proteins in human lung cancer cell lines. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1998;19:522–9. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.19.3.3181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mason JC, Yarwood H, Sugars K, Morgan BP, Davies KA, Haskard DO. Induction of decay-accelerating factor by cytokines or the membrane-attack complex protects vascular endothelial cells against complement deposition. Blood. 1999;94:1673–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bjorge L, Jensen TS, Ulvestad E, Vedeler CA, Matre R. The influence of tumour necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1 beta and interferon-gamma on the expression and function of the complement regulatory protein CD59 on the human colonic adenocarcinoma cell line HT29. Scand J Immunol. 1995;41:350–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1995.tb03578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gasque P, Morgan BP. Complement regulatory protein expression by a human oligodendrocyte cell line: cytokine regulation and comparison with astrocytes. Immunology. 1996;89:338–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.d01-756.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arenzana N, Rodriguez de Cordoba S. Promoter region of the human gene coding for beta-chain of C4b binding protein. Hepatocyte nuclear factor-3 and nuclear factor-I/CTF transcription factors are required for efficient expression of C4BPB in HepG2 cells. J Immunol. 1996;156:168–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]