Abstract

Intestinal epithelial cells seem to play a key role during IBD. The network of cellular interactions between epithelial cells and lamina propria mononuclear cells is still incompletely understood. In the following co-culture model we investigated the influence of intestinal epithelial cells on cytokine expression of T cytotoxic and T helper cells from patients with IBD and healthy controls. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were purified by a Ficoll–Hypaque gradient followed by co-incubation with epithelial cells in multiwell cell culture insert plates in direct contact as well as separated by transwell filters. We used Caco-2 cells as well as freshly isolated colonic epithelia obtained from surgical specimens. Three-colour immunofluorescence flow cytometry was performed after collection, stimulation and staining of PBMC with anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-IFN-γ and anti-IL-4. Patients with IBD (Crohn's disease (CD), n = 12; ulcerative colitis (UC), n = 16) and healthy controls (n = 10) were included in the study. After 24 h of co-incubation with Caco-2 cells we found a significant increase of IFN-γ-producing CD8+ lymphocytes in patients with IBD. In contrast, healthy controls did not respond to the epithelial stimulus. No significant differences could be found between CD and UC or active and inactive disease. A significant increase of IFN-γ+/CD8+ lymphocytes in patients with UC was also seen after direct co-incubation with primary cultures of colonic crypt cells. The observed epithelial–lymphocyte interaction seems to be MHC I-restricted. No significant epithelial cell-mediated effects on cytokine expression were detected in the PBMC CD4+ subsets. Patients with IBD—even in an inactive state of disease—exert an increased capacity for IFN-γ induction in CD8+ lymphocytes mediated by intestinal epithelial cells. This mechanism may be important during chronic intestinal inflammation, as in the case of altered mucosal barrier function epithelial cells may become targets for IFN-γ-producing CD8+ lymphocytes.

Keywords: mononuclear cells, CD8+ lymphocytes, interferon-gamma, intestinal epithelial cells, inflammatory bowel disease

Introduction

Intestinal epithelial cells (iEC) play a key role in the initiation and perpetuation of intestinal inflammation [1–6]. They are recognized as central players in regulating the natural and acquired immune system of the host at mucosal surfaces. In vivo normal human iEC do not express costimulatory molecules. On the other hand, iEC can take up soluble polypeptides and activate CD8+ lymphocytes. GP180, a novel member of the immunoglobulin supergene family, appears to be a key ligand on the surface of intestinal epithelial cells for the CD8 molecule on T cells [7].

Until now the network of cellular interactions between epithelial cells and lamina propria mononuclear cells (LPMNC) or peripheral mononuclear cells has been only incompletely understood. It has been shown that T cell/monocyte interactions influence epithelial physiology in states of inflammation [8]. T cells and T cell-derived cytokines induce and regulate mucosal immune responses, e.g. stimulation of epithelial proliferation, expression of MHC antigens and modulation of epithelial secretory activities [9, 10]. It could also be demonstrated that iEC influence T lymphocytes as they down-regulate intraepithelial lymphocytes [11]. In IBD, many immunoregulatory abnormalities in intestinal and peripheral T lymphocytes are noted. This includes, for instance, the altered ratio of proinflammatory to immunosuppressive cytokines, the selective activation of T-helper lymphocyte subsets and abnormalities in epithelial antigen presentation (for review, see [12]). There is increasing evidence that iEC can function as non-professional antigen-presenting cells. When activated by iEC during the initial inflammatory process, macrophages and T cells secrete a large number of proinflammatory cytokines, which recruit other inflammatory cell types. Activated macrophages initiate a T cell cascade, which leads to secretion of a variety of cytokines followed by recruitment of several other cell types. IFN-γ seems to be one of the key cytokines during intestinal inflammation. It has been shown to increase mucosal permeability by injuring epithelial tight junctions [13]. Recent studies indicate that the occurrence of intestinal inflammation is regulated by reciprocal IFN-γ and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) responses [14]. Tissue injury and epithelial damage with consecutive regeneration processes are the net result of soluble products and activated inflammatory lymphocytes [3].

According to the hypothesis of the existence of preactivated T cells stimulated by iEC during IBD we established a human co-culture system to analyse T cell cytokine profiles in mono- and dual-compartment systems with epithelial cells. To differentiate between type-1 and type-2 responses in T-helper and T cytotoxic subsets, we used the marker cytokines IFN-γ and IL-4, reflecting and identifying Th1/Th2 as well as Tc1/Tc2 responses by the epithelial stimulus.

We were able to demonstrate that CD8+ lymphocytes from patients with IBD have a high capacity for IFN-γ induction by iEC.

Subjects and methods

Study population

Peripheral mononuclear cells taken from 40 ml EDTA blood were analysed from healthy volunteers and patients suffering from ulcerative colitis (UC) or Crohn's disease (CD). Patients were recruited by the Department of Medicine B of the University of Münster. Activity of disease was defined by the Rachmilewitz index in patients with UC [15] and by the Crohn's disease activity index (CDAI) in patients with CD [16]. Colonic epithelia were obtained from patients undergoing surgical resection (e.g. colectomy, hemicolectomy or segmental resection), either in the case of CD or UC or in the case of, for example, colonic tumours or diverticulitis.

Co-culture studies were performed in 16 patients with UC, 12 patients with CD and 10 controls (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Crohn's colitis | Ulcerative colitis | Control | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | n = 6 | n = 9 | n = 9 |

| Female | n = 6 | n = 7 | n = 1 |

| CDAI/CAI | 133 | 4·83 | Neg. |

| Leucocyte count (/μl) mean | 10 200 | 8430 | 6600 |

| Platelet count (/μl) mean | 380 000 | 333 000 | 280 000 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dl) mean | 13·2 | 13·6 | 13·8 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dl) mean | 2·78 | 1·4 | Neg. |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dl) mean | 378 | 461 | 258 |

| BSG mm 1st hour mean | 12·9 | 14·9 | 5·0 |

| Extra-intestinal symptoms | Arthritis 2/12 | Arthritis 1/16 | 0/10 |

| Fistula 1/12 | Periostitis 1/16 | ||

| Stomatitis 1/12 | |||

| Mesalazine | 10/12 | 15/16 | 0/10 |

| Azathioprine | 1/12 | 0/16 | 0/10 |

| Steroids/Budesonide | 8/12 | 11/16 | 0/10 |

| Ranged from 4 to 60 mg | Ranged from 7·5 to 35 mg |

Co-cultures of primary intestinal epithelial crypt cells and peripheral mononuclear cells in an autologous system were made with six patients (three UC patients, three controls).

All patients had given written informed consent to participate in the study. The study protocol was approved by the Human Studies Committee of the University of Münster.

Isolation procedure

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from healthy volunteers and IBD patients taken from EDTA blood were purified by Ficoll–Hypaque density gradient centrifugation [17]. For this purpose, whole blood was carefully layered on Ficoll solution (density 1·077). Centrifugation (Beckman, Fullerton, CA, USA) was performed for 40 min at 600 g at room temperature. The mononuclear cell interphase was taken, washed in PBS (including Ca2+, Mg2+ Seromed, Berlin, FRG) and finally centrifuged three times for 10 min at 400 g. This procedure was followed by haemolysis, which was achieved by short incubation with 0·83% NH4Cl pH 7·2. (Gey's solution). Purified mononuclear cells were washed again as mentioned above. Finally, they were resuspended in RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) medium, containing 10% human serum, 1% glutamine (2 mm), 1% non-essential amino acids and penicillin (50 U/ml)/streptomycin (50 μg/ml). Viability was checked by trypan blue exclusion (0·1% trypan blue). Cells were counted in a Neubauer chamber and plated in 24-well cell culture insert plates (Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Lymphocytes

To exclude monocyte interference in lymphocyte/iEC interaction, highly purified lymphocytes were generated after Ficoll density gradient centrifugation by monocyte depletion on plastic surfaces after 3 h of adherence. Non-adherent lymphocytes were flushed with PBS including Ca2+ and Mg2+. Lymphocyte purity could be demonstrated by subsequent flow cytometry in FSC/SSC analysis. Purity was > 90%.

Intestinal epithelial cells

Caco-2 colonic carcinoma cell line

Caco-2 cells, a well established human colonic carcinoma cell line (ATCC, Rockville, MD [18]), were cultured under standard conditions in MEM medium containing 10% human serum and standard supplements. We used early passages (15 up to 30) in the co-culture experiments. Cells grew to monolayers and were trypsinized after Ca2+ complexation with EDTA. In subsequent steps they were washed and resuspended in RPMI medium. Co-cultures were performed with PBMC.

Primary cultures of colonic crypt cells

Primary cultures of colonic crypt cells were prepared according to a modification of the procedure described by evans et al. [19] and flint et al. [20]. Resected large bowel tissue was immediately placed on ice-cold high glucose medium 199 after longitudinal dissection of the tissue wall and removal of adventitia and serosa. After removing remaining endoluminal macroparticles and detritus, small pieces of tissue were intensively rinsed with PBS including Ca2+, Mg2+ up to eight times. Mucus was partially removed by short incubation with 1 mm DTT (Sigma, Deisenhofen, FRG) by orbital shaking (15 min). Afterwards, the mucosa was scraped off the submucosa with a scalpel and thin mucosal layers were placed into a small volume of saline solution (including Ca2+, Mg2+). Thin mucosal pieces were minced by a crossed scalpel technique before they were placed into a collagenase IX (300 U/ml, 0·25 mg/ml; Sigma)/dispase I (0·1 mg/ml; Boehringer, Indiannapolis, IN, USA) digestion cocktail for at least 30 min. Crypt isolates were moderately shaken at 70 rev/min at room temperature. Tissue disintegration and crypt isolation could be observed by increasing turbidity of the cocktail. Colonic crypt formations were centrifuged twice at 110 g for 4 min without deceleration and the supernatant was carefully removed. Finally, crypts were resuspended in RPMI medium and co-cultures were performed with PBMC in rat collagen type I (4 μg/ml)-coated culture inserts for adherence improvement. Viability of the isolated crypts was checked by trypan blue exclusion (0·1% trypan blue), viability of crypt cells ranged from 85% to 89% (mean) 30 min after isolation procedure and remained at 70–75% (mean) after 48 h of culture. To determine the purity of primary epithelial cell preparations flow cytometric analysis was performed after 24 h with monocultured epithelial cells using a specific epithelial glycoprotein surface marker (Ber-EP4) and CD markers for lymphocyte subpopulations to calculate the lymphocytic contamination. Purity of epithelial cells after preparation was > 90%. Contamination by CD4 and CD8 lymphocytes < 5%.

Co-culture conditions

PBMC as well as monocyte-depleted T cells were co-cultured with iEC (Caco-2 or primary cultures of colonic crypts) in 24-well cell culture insert plates (Falcon) in direct contact as well as separated by transwell filters (0·4 μm; Falcon) using a 10:1 (2 × 106/2 × 105 cells/well) effector:target ratio. PBMC monocultures served as controls. Co-cultures were performed over a total time of 24 h in supplemented RPMI 1640 containing 10% human serum under standard culture conditions (5% CO2 and 37°C).

Soluble IL-12 pathway blocking

Monocyte cytokine interference concerning the IL-12 pathway with initiation of type-I responses in T cell–iEC interaction was investigated and excluded by IL-12 (p40/70) blocking experiments with anti-IL-12 antibody (p40/70) before co-culture was started. We used the neutralizing mouse IgG1 C8.6 anti-human IL-12 (p40/70) antibody (PharMingen, Heidelburg, FRG) in concentrations from 10 to 1000 ng/ml.

MHC I-restricted signalling blocking

To differentiate between stimulatory or inhibitory effects mediated by soluble mediators or surface–surface interactions, MHC I-restricted interactions between peripheral CD28+CD8+ T cells and iEC were blocked by anti-MHC I antibody (mouse IgG1κ, clone G46-2.6 anti-human HLA A/B/C; PharMingen) in concentration ranges from 1 to 5 μg/ml.

Cell preparation for flow cytometric analysis

After 24 h of co-culture cells were collected and stimulated with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA, 1 ng/ml; Sigma), additionally with ionomycin, a Ca2+ ionophore (1 μm; Sigma), and monensin (3 μm; Sigma) for 4 h at 37°C/5% CO2. To prevent insufficient stimulation caused by cell sedimentation, samples were resuspended every 15 min. After paraformaldehyde (PFA) fixation (4% PFA in PBS including Ca2+, Mg2+ Merck, Darmstadt, FRG) cells were permeabilized with 0·1% saponin (Fluka, Sigma).

According to this frequently described procedure [21], three-colour immunofluorescence labelling was done with anti-CD4 (Cychrome®, clone RPA-T4 mouse IgG1) or anti-CD8 (Cychrome®, clone RPA-T8 mouse IgG1) anti-IFN-γ (FITC, clone 4S.B3 mouse IgG1) and anti-IL-4 (PE, clone 8D4-8 mouse IgG1, all Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, FRG). Finally, flow cytometric analysis was performed with Becton Dickinson FACScan. Data generated form each sample included 10 000 counted cells.

Statistical analysis

Dot plots were analysed by WinMDI. Patients' statistics were processed with Sigma Plot and SPSS by use of Wilcoxon test for non-parametrically distributed paired samples and Mann–Whitney U-test for unpaired intergroup comparison. P < 0·05 was considered significant.

Results

Influence of iEC on intracellular IFN-γ and IL-4expression in CD8+ and CD4+ lymphocyte populations

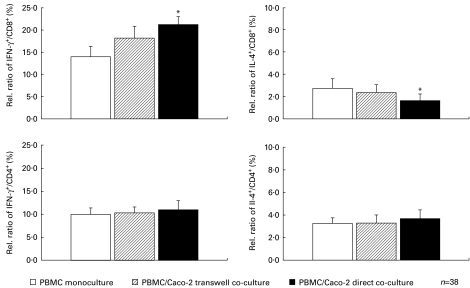

IFN-γ- and IL-4-producing T lymphocytes were examined in the whole study population. After 24 h of co-incubation with Caco-2 cells at a 10:1 effector:target ratio we found a 48% increase of IFN-γ-producing CD8+ lymphocytes (21·23 ± 1·8% versus 13·97 ± 2·3%, P = 0·025, n = 38; direct co-culture versus control, mean ± s.e.m.). A slight decrease of IL-4+/CD8+ lymphocytes (ratio means proportion of IL-4 and CD8 double-positive stained subpopulation out of whole positive stained CD8 population) was observed in this set (2·73 ± 0·9% versus 1·62 ± 0·6%; P = 0·05, n = 38; control versus direct co-culture). A similar but not significant tendency was observed in Caco-2 transwell co-incubation experiments with a 24% increase of IFN-γ+/CD8+ lymphocytes (18·20 ± 2·6% versus 13·97 ± 2·3%, P > 0·05, n = 38; transwell versus control; ratio means proportion of IFN-γ and CD8 double-positive stained subpopulation out of whole positive stained CD8 population) and a slight decrease of IL-4+/CD8+ lymphocytes (2·73 ± 0·9% versus 2·35 ± 0·7%, P > 0·05, n = 38; control versus transwell) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Influence of intestinal epithelial cells on intracellular IFN-γ and IL-4 expression in CD8+ and CD4+ lymphocyte populations. After 24 h co-incubation of 2 × 105 peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from the whole study group with 2 × 106 Caco-2 cells, samples were prepared, stimulated and stained for intracellular FACS analysis. A significant increase of IFN-γ-producing CD8+ lymphocytes (+48%; *P = 0·025; n = 38) was observed by direct short-term co-culture with Caco-2 cells (▪, upper left graph, compared with PBMC monoculture, □ = 100%). A decrease of IL-4+/CD8+ lymphocytes was also measured in this set (−41%; *P = 0·05, upper right graph). A similar trend was found in Caco-2 transwell co-incubation experiments with an increase of IFN-γ+/CD8+ (+24%; P > 0·05) and a slight decrease of IL-4+/CD8+ (−15%; P > 0·05). Intracellular IFN-γ and IL-4 analysed in CD4+ lymphocytes showed no shifting after co-culture with Caco-2 cells.

Concerning CD4+ lymphocytes, we did not observe any effect on cytokine production either when using transwell co-incubation or during direct co-culture (Fig. 1).

In contrast to healthy controls, CD8+ lymphocytes from patients with IBD are strongly inducible for IFN-γ production after co-culture with iEC

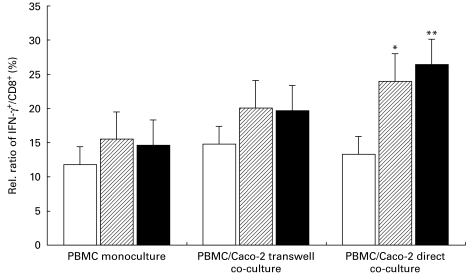

T cell subgroup analysis between controls and IBD patients showed differences in basal IFN-γ expression and increase of IFN-γ in CD8+ lymphocytes by iEC after 24 h co-culture. IBD patients revealed a tendency to increased basal intracellular IFN-γ expression (15·5 ± 4·1%, IFN-γ+/CD8+ in CD; and 14·6 ± 2·9%, IFN-γ+/CD8+ in UC versus 11·8 ± 2·3%, IFN-γ+/CD8+ in the control group, P > 0·05). Intracellular IFN-γ production was strongly inducible by iEC in CD8+ lymphocytes in IBD patients, even in patients with inactive disease, whereas controls responded only poorly to the epithelial stimulus. We observed an increase of IFN-γ expression from 15·5% to 20·1 ± 5·6% in transwell samples (P > 0·05) and a further increase up to 24·0 ± 5·8%, IFN-γ+/CD8+ in direct co-cultures (P = 0·012 compared with monoculture) in patients suffering from CD. UC patients revealed a similar strong induction of intracellular IFN-γ signal from 19·7 ± 3·5% up to 26·4 ± 4·7%, IFN-γ+/CD8+ lymphocytes in transwell (P > 0·05) and direct co-cultures (P = 0·0058 compared with monoculture) corresponding to a basic expression of 14·6% IFN-γ+/CD8+ lymphocytes (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

In contrast to healthy controls, cytotoxic lymphocytes of patients with inactive IBD were strongly inducible for IFN-γ by epithelial cell stimulus. After 24 h co-incubation of 2 × 105 peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) with 2 × 106 Caco-2 cells, samples were prepared, stimulated and stained for intracellular FACS analysis. Cytotoxic T cell subgroup analysis between healthy controls (□, n = 10) and IBD patients (ulcerative colitis (UC), ▪, n = 16; Crohn's disease (CD), hatched, n = 12) demonstrates differences in basal IFN-γ expression and an increase of IFN-γ-producing lymphocytes by intestinal epithelial cells (iEC) after 24 h co-culture. IFN-γ was strongly inducible by iEC in CD8+ lymphocytes in CD and UC patients, whereas controls only poorly responded to the epithelial stimulus. An increase of IFN-γ from 15·5% to 20·1% in transwell samples and a further increase up to 24·0% in direct PBMC/Caco-2 co-cultures (*P = 0·012) with patients suffering from CD were determined. UC patients showed a similarly strong induction of the intracellular IFN-γ signal in CD8+/IFN-γ+ lymphocytes in transwell and direct co-cultures (**P = 0·0058).

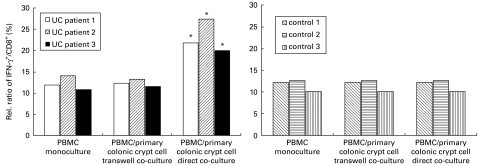

IFN-γ induction in CD8+ lymphocytes in co-culture with autologous primary colonic crypt cells in UC patients

A significant increase of IFN-γ+/CD8+ lymphocytes (+81%, P = 0·014) was measured after direct co-incubation of peripheral mononuclear cells with primary cultures of colonic crypt cells in an autologous co-culture system in patients with UC (n = 3). Co-cultures showed a significant shift in the distribution of the IFN-γ+/CD8+ population resulting in 22·97 ± 2·2% IFN-γ+/CD8+ lymphocytes in UC patients' lymphocytes directly co-cultured with autologous intestinal crypts (related to 12·27% in control sample). We did not observe any significant IFN-γ induction in transwell preparations (12·27 ± 0·9% versus 12·33 ± 0·4% in control versus transwell subsets). Transwell and direct co-culture subsets showed no significant differences in the control group compared with monoculture preparations (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

IFN-γ induction of cytotoxic lymphocytes in ulcerative colitis (UC) patients by co-culture of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) with autologous primary colonic crypt cells. After 24 h co-incubation of 2 × 105 PBMC with 2 × 106 primary colonic crypt cells in transwell and direct co-culture, samples were prepared, stimulated and stained for intracellular FACS analysis. A significant increase of IFN-γ+/CD8+ lymphocytes (+81% mean, *P = 0·014) was measured after direct co-incubation of peripheral mononuclear cells with primary cultures of colonic crypt cells in an autologous co-culture system in the UC patient group (n = 3). No significant induction was observed in the control group (n = 3) or in any transwell preparation.

No significant epithelial cell-mediated effects on cytokine expression were detected in the CD4+ subsets of peripheral mononuclear cells in primary colonic crypt cell co-cultures (data not shown).

Epithelial cell-mediated IFN-γ induction in peripheral cytotoxic lymphocytes does not depend on monocytes

To exclude monocyte interference in the cellular network of cytotoxic cells with iEC we depleted monocytes from PBMC. Monocyte-depleted lymphocyte preparations were used for repetition of co-culture experiments with transwell and direct cell–cell contact co-culture samples. We were able to confirm that cytotoxic cell–iEC interaction is a monocyte-independent cell–cell communication system. IFN-γ rose to 11·55% in transwell and 13·29% in direct co-culture compared with the basal expression of 7·02% in CD8+ lymphocytes. Monocyte contamination was < 5%.

The addition of a neutralizing anti-IL-12 (p40/p70) antibody at the beginning of 24 h co-culture of iEC and peripheral mononuclear cells with different concentrations (10–1000 ng/ml) showed no interference with IFN-γ induction in PBMC. In this set we also observed a nearly two-fold increase in direct co-cultures of PBMC and Caco-2 cells. The IFN-γ signal showed no quantitative decrease in CD8+ cells in concentration ranges of anti‐IL-12 from 10 ng/ml to 1000 ng/ml (data not shown). Therefore, we conclude that the observed epithelial cell-mediated IFN-γ induction in CD8+ lymphocytes is based on an IL-12-independent pathway or interaction.

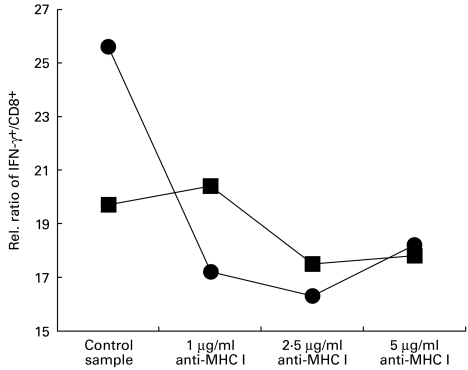

MHC I-restricted signalling blockade with anti-MHC I antibody

Addition of anti-MHC I antibody (mouse IgG1, κ, clone G46-2.6) at concentrations ranging from 1 to 5 μg/ml suggests that IFN-γ induction in our co-culture system was partially transduced by MHC I molecules. After 24 h of monoculture and direct co-culture (conditions described above), we observed a down-regulation of the intracellular IFN-γ signal in direct co-cultures incubated with anti-MHC I to values below those of basal expression of monoculture samples. In detail, we measured 25·6% IFN-γ+/CD8+ lymphocytes in direct co-culture samples versus 19·7% IFN-γ+/CD8+ lymphocytes in control monocultures, reflecting the induction circuit by iEC. Intracellular IFN-γ signal in direct co-culture was markedly decreased by anti-MHC I antibody (17·2% IFN-γ+/CD8+, 16·3% IFN-γ+/CD8+ and 18·2% IFN-γ+/CD8+ with concentrations of 1, 2·5 and 5 μg/ml anti-MHC I compared with 25·6% IFN-γ+/CD8+ lymphocytes in direct co-culture control sample (Fig. 4)).

Fig. 4.

Interaction between intestinal epithelial cells (iEC) and CD8+ lymphocytes is MHC I-restricted. Interactions between peripheral CD8+ cytotoxic T cells and iEC were blocked by anti-MHC I antibody (mouse IgG1κ, clone G46-2.6 anti-human HLA A/B/C; PharMingen) in concentration ranges from 1 to 5 μg/ml. After 24 h of monoculture (▪) and direct co-culture (•) a down-regulation was observed of the intracellular IFN-γ signal in direct co-cultures incubated with anti-MHC I to values below those of basal expression of monoculture samples. In our co-culture system IFN-γ induction may therefore be partially transduced by MHC I molecules. Data represent results of four independent experiments with similar results.

Discussion

We present a human co-culture model with iEC that are capable of inducing IFN-γ production in CD8+ lymphocytes from patients with IBD.

Interaction between iEC and T lymphocytes has been determined in earlier studies [22]. It has been shown that enterocytes can act as stimulators in an allogeneic mixed lymphocyte type response [23–25]. It has been further demonstrated that iEC preferentially stimulate proliferation of CD8+ T cells [26, 27]. This process seems to be regulated by epithelial MHC I expression [28] and by the non-classical MHC class I molecule CD1d [25, 29]. The stimulatory signal has been suggested to be mediated by a 180-kD glycoprotein (gp180) that is expressed on normal iEC, which binds to CD8 and activates the CD8-associated tyrosine kinase p56lck [7]. In our study we used peripheral T lymphocytes which were co-cultured with iEC, as it is a well-known fact that peripheral lymphocytes offer more stable conditions and provide more reliable data compared with studies done with lamina propria lymphocytes [30]. In fact, there are many differences in phenotypic pattern and immunoregulatory responses of LPMNC and PBMC to an epithelial stimulus, as has previously been demonstrated by in vitro data [31]. However, the isolation procedure of LPMNC is much more difficult compared with that of PBMC and always contains digestive or chelating steps with consecutive alterations in CD and cytokine pattern. This results in artificial stimulation or inhibition of LPMNC for technical reasons. There are also many individual differences concerning LPMNC distribution, reflecting the degree of inflammation or leucocyte infiltration or the level of individual stimulation depending on the local mucosal milieu. This needs histological correlation for interpreting flow cytometric co-culture results and complicates interindividual comparison. Regarding these aspects as well as the fact that there is a recruitment of PBMC from the circulation at an inflamed site during IBD, generation of peripheral leucocytes has been preferred in our study. Our human co-culture model does not reflect the in vivo situation but allows us to study cellular interactions between distinct cell populations in vitro to specify immunological behaviour in IBD patients compared with a control group.

Our data show stimulation of CD8+ lymphocytes from IBD patients by iEC with increased capacity to produce IFN-γ. IFN-γ stimulation was more intense after direct co-culture in a single compartment compared with co-culture experiments performed in transwell tissue culture plates. This observation suggests that not only soluble factors are responsible for the observed interaction, and cell–cell contacts predominate over effects induced by soluble mediators. A potential signal transducer in cellular interaction between mononuclear cells—or better, T lymphocytes—and iEC may be the MHC I complex. This could be confirmed by our MHC I blocking experiments, thereby inhibiting intracellular IFN-γ up-regulation. IFN-γ induction in CD8+ lymphocytes therefore seems to be driven, at least in part, by an MHC I-restricted pathway. It might also be speculated that in our study the interaction between iEC and CD8+ lymphocytes with increased production of IFN-γ is mediated by monocytes in the PBMC population. Recent studies have shown that IFN-γ can be induced in T lymphocytes by monocyte-derived IL-12 [32]. As monocyte/macrophage-derived IL-12 production seems to be up-regulated in CD patients [33], it is conceivable that in our study IFN-γ induction may be brought about by IL-12. However, IL-12-mediated effects could be excluded by neutralization with an anti-IL-12 antibody that did not affect interaction between iEC and T lymphocytes. We could further demonstrate that depletion of monocytes from PBMC did not affect IFN-γ stimulation either in CD8+ lymphocytes, suggesting that the observed mechanisms are solely driven by interactions between epithelial cells and T lymphocytes.

We found that IFN-γ production in CD8+ lymphocytes from patients with IBD—even during inactive disease—was markedly up-regulated during co-culture with Caco-2 cells as well as with freshly isolated iEC. In contrast, healthy controls did not show any alteration of IFN-γ production. Concerning IL-4-producing CD8+ lymphocytes in the whole study population, there was a significant down-regulation (P = 0·05) after co-culture with iEC. However, concerning UC and CD patients, we could only observe the tendency to diminished IL-4-producing cells, not however reaching the level of significance (data not shown). Therefore, in IBD patients IL-4 regulation does not seem to play a major role during the interaction between epithelial cells and T lymphocytes. Nor have CD4+ lymphocytes been affected in our co-culture system. Even in an autologous co-culture system with intestinal crypt cells and peripheral mononuclear cells from patients with UC, we observed only increased numbers of IFN-γ-producing CD8+ lymphocytes but no effect in the CD4+ population. The fact that cytokine production on CD4+ lymphocytes did not seem to be involved in our co-culture system seems to be in contrast to recent findings suggesting that only CD4+ but not CD8+ lymphocytes are involved in epithelial–lymphocyte interactions during IBD [27, 34]. However, in these studies cytokine production in T lymphocytes during UC and CD was not determined. A recent study by Toy et al. found defective gp180 expression in CD and UC patients that may be responsible for CD4 activation by iEC during IBD [34]. However, this study also demonstrated that not only CD4+ cells but also—to a lesser extent—CD8+ lymphocytes could be stimulated during co-culture with epithelial cells.

IFN-γ is known to up-regulate macrophage IL-12 production, thereby enhancing inflammatory activity [35]. It has also been shown that IFN-γ affects intestinal permeability during inflammation [13] and modulates CD1d expression on epithelial cells [36]. Increased activation of CD8+ lymphocytes may be important during intestinal inflammation, as in case of altered mucosal barrier function—especially during mucosal inflammation—epithelial cells may become targets for CD8+ lymphocytes with cytotoxic phenotype. Cytotoxic action of peripheral leucocytes against human fetal colon cells has been shown in an early in vitro study by Broberger & Perlmann [37]. During IBD and especially in CD the intestinal mucosa can be infiltrated diffusely by immune cells, including T lymphocytes, despite the absence of morphological, endoscopic or clinical evidence of inflammation [38]. CD8+ cytotoxic effector lymphocytes have been shown to be increased numerically in patients with IBD [39]. It is therefore conceivable that increased numbers of IFN-γ-producing CD8+ lymphocytes induced by epithelial cells, even in uninvolved tissue, are responsible for permanent inflammatory activity within the intestine. Our data showing slightly increased IFN-γ levels even in unstimulated peripheral CD8+ lymphocytes from patients with inactive IBD and strong induction capacity after co-culture with iEC demonstrate that T cells are in an activated state in patients with IBD even in a state of clinical remission. In our study, increased numbers of IFN-γ-producing CD8+ lymphocytes have been shown in patients not only with inactive but also with highly active IBD. However, there was no significant difference concerning IFN-γ production in CD8+ lymphocytes between active and inactive disease (data not shown). Therefore, it might be suggested that during intestinal inflammation activated iEC stimulate preactivated CD8+ T lymphocytes by direct contact or by soluble mediators, thereby inducing a strong IFN-γ production with induction of long-lasting inflammatory activity.

Our data demonstrating a direct interaction between iEC and T lymphocytes are supported by findings of Arosa et al. [40], who recently characterized the interactions between peripheral blood CD8 lymphocytes and iEC. They phenotyped the CD8+CD28− population as antigen-experienced T cells, down-regulating CD28 after TCR-mediated stimulation. A large number of these CD8+ effector T cells may be recruited during the development of intestinal inflammation.

In conclusion, we were able to demonstrate that epithelial cells reveal high induction capacity to stimulate CD8+ lymphocytes from patients with IBD to strongly express IFN-γ. The interaction observed in our co-culture system may partially be mediated by MHC I molecules. It is suggested that IFN-γ induction might be an important mechanism for chronification of intestinal inflammation, as IFN-γ has been shown to play a major role in the IBD process.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Wilhelm Sander-Stiftung (Grant 96.046.1).

REFERENCES

- 1.MacDermott RP. Alterations of the mucosal immune system in inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:907–16. doi: 10.1007/BF02358624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christ AD, Blumberg RS. The intestinal epithelial cell: immunological aspects. Springer Semin Immunpathol. 1997;18:449–16. doi: 10.1007/BF00824052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sartor RB. Pathogenesis and immune mechanisms of chronic inflammatory bowel diseases. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:5S–11S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kagnoff MF. Mucosal immunology: new frontiers. Immunol Today. 1996;17:57–59. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)80579-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jung HC, Eckmann L, Yang SK, et al. A distinct array of proinflammatory cytokines is expressed in human colon epithelial cells in response to bacterial invasion. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:55–65. doi: 10.1172/JCI117676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reinecker HC, Loh EY, Ringler DJ, et al. Monocyte-chemoattractant protein 1 gene expression in intestinal epithelial cells and inflammatory bowel disease mucosa. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:40–50. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y, Yio XY, Mayer L. Human intestinal epithelial cell-induced CD8+ T cell activation is mediated through CD8 and the activation of CD8-associated p56lck. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1079–88. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.4.1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKay DM, Croitoru K, Perdue MH. T-cell–monocyte interactions regulate epithelial physiology in a co-culture model of inflammation. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:C418–28. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.270.2.C418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kucharzik T, Lügering N, Weigelt H, et al. Immunoregulatory properties of IL-13 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease; comparison with IL-4 and IL-10. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;104:483–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.39750.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pullman WE, Elsbury S, Kobayashi M, et al. Enhanced mucosal cytokine production in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:529–37. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90100-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamamoto M, Fujihashi K, Kawabata K, et al. A mucosal intranet: intestinal epithelial cells down-regulate intraepithelial, but not peripheral T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1998;160:2188–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fiocchi C. Inflammatory bowel disease: etiology and pathogenesis. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:182–205. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madara JL, Stafford J. Interferon-γ directly affects barrier function of cultured intestinal epithelial monolayers. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:724–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI113938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strober W, Kelsall B, Fuss I, et al. Reciprocal IFN-γ and TGF-β responses regulate the occurrence of mucosal inflammation. Immunol Today. 1997;18:61–64. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01000-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rachmilewitz D. Coated mesalazine (5-amino-salicylic acid) versus sulphasalazine in the treatment of active ulcerative colitis—a randomized trial. BMJ. 1989;198:82–84. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6666.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Best WR, Becktel JM, Singleton JW, et al. Development of a Crohn's disease activity index: national cooperative Crohn's disease study. Gastroenterology. 1976;101:782–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romeu MA, Mestre M, Gonzalez L, et al. Lymphocyte immunophenotyping by flow cytometry in normal adults. Comparison of fresh whole blood lysis technique, Ficoll–Paque separation and cryopreservation. J Immunol Methods. 1992;154:7–10. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(92)90206-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jumarie C, Malo C. Caco-2 cells cultured in serum-free medium as a model for the study of enterocytic differentiation in vitro. J Cell Physiol. 1991;149:24–33. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041490105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evans GS, Flint N, Somers AS, Eyden B, Potten CS. The development of a method for the preparation of rat intestinal epithelial cell primary cultures. J Cell Sci. 1992;101:219–31. doi: 10.1242/jcs.101.1.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flint N, Cove FL, Evans GS. A low-temperature method for the isolation of small intestinal epithelium along the crypt–villus axis. Biochem J. 1991;280:331–4. doi: 10.1042/bj2800331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prussin C. Cytokine flow cytometry: understanding cytokine biology at the single cell level. J Clin Immunol. 1997;17:195–203. doi: 10.1023/a:1027350226435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Panja A, Barone A, Mayer L. Stimulation of lamina propria lymphocytes by intestinal epithelial cells: evidence for recognition of non classical restriction elements. J Exp Med. 1994;179:943–50. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.3.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bland PW, Warren LG. Antigen presentation by epithelial cells of the rat small intestine. I. Kinetics, antigen specificity and blocking by anti-Ia antisera. Immunology. 1986;58:1–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayer LL, Shlien R. Evidence for function of Ia molecules on gut epithelial cells in man. J Exp Med. 1987;166:1471–83. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.5.1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoang P, Crotty B, Dalton HR, et al. Epithelial cells bearing class II molecules stimulate allogeneic human colonic intraepithelial lymphocytes. Gut. 1992;33:1089–93. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.8.1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bland PW, Warren LG. Antigen presentation by epithelial cells of the rat small intestine. II. Selective induction of suppressor T cells. Immunology. 1986;58:9–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mayer LL, Eisenhardt D. Lack of induction of suppressor T cells by intestinal epithelial cells from patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:1255–60. doi: 10.1172/JCI114832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campbell NA, Mayer L. Intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) target a subpopulation of CD8+ T cells which are pre-committed to have a suppressor phenotype. Gastroenterology. 1999;116A:G2948. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panja A, Blumberg RS, Balk SP, et al. CD1d is involved in T cell–intestinal epithelial cell interactions. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1115–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.3.1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ebert EC, Roberts AI. Pitfalls in the characterization of small intestinal lymphocytes. J Immunol Methods. 1995;178:219–27. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)00259-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Niessner M, Volk BA. Phenotypic and immunoregulatory analysis of intestinal T-cells with inflammatory bowel disease: evaluation of an in vitro model. Eur J Clin Invest. 1995;25:155–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1995.tb01542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12: a cytokine produced by antigen-presenting cells with immunoregulatory functions in the generation of T-helper cells type I and cytotoxic lymphocytes. Blood. 1994;84:4006–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Monteleone G, Biancone L, Marasco R, et al. Interleukin 12 is expressed and actively released by Crohn's disease intestinal lamina propria mononuclear cells. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1169–78. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70128-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Toy LS, Yio XY, Lin A, et al. Defective expression of gp180, a novel CD8 ligand on intestinal epithelial cells, in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2062–71. doi: 10.1172/JCI119739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma X, Chow JM, Cri G, et al. The interleukin 12 p40 gene promoter is primed by interferon γ in monocytic cells. J Exp Med. 1996;183:147–57. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Colgan SP, Morales VM, Madara JL, et al. IFN-gamma modulated CD1d surface expression on intestinal epithelia. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:C276–C283. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.1.C276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perlmann P, Broberger O. In vitro studies of ulcerative colitis. II. Cytotoxic action of white blood cells from patients on human fetal colon cells. J Exp Med. 1963;117:717–33. doi: 10.1084/jem.117.5.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oberhuber G, Puspok A, Oesterreicher C, et al. Focally enhanced gastritis: a frequent type of gastritis in patients with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:698–706. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9041230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muller S, Lory J, Corazza N, et al. Activated CD4+ and CD8+ cytotoxic cells are present in increased numbers in the intestinal mucosa from patients with active inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:261–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arosa FA, Irwin C, Mayer L, et al. Interactions between peripheral blood CD8 T-lymphocytes and intestinal epithelial cells (iEC) Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;112:226–36. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00566.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]