Abstract

In peripheral blood the majority of circulating monocytes present a CD14highCD16− (CD14++) phenotype, while a subpopulation shows a CD14lowCD16+ (CD14+CD16+) surface expression. During haemodialysis (HD) using cellulosic membranes transient leukopenia occurs. In contrast, synthetic biocompatible membranes do not induce this effect. We compared the sequestration kinetics for the CD14+CD16+ and CD14++ monocyte subsets during haemodialysis using biocompatible dialysers. Significant monocytopenia, as measured by the leucocyte count, occurred only during the first 30 min. However, remarkable differences were observed between the different monocyte subsets. CD14++ monocyte numbers dropped to 77 ± 13% of the predialysis level after 15 min, increasing to ≥ 93% after 60 min. In contrast, the CD14+CD16+ subset decreased to 33 ± 15% at 30 min and remained suppressed for the course of dialysis (67 ± 11% at 240 min). Approximately 6 h after the end of HD the CD14+CD16+ cells returned to basal levels. Interestingly, the CD14+CD16+ monocytes did not show rebound monocytosis while a slight monocytosis of CD14++ monocytes was occasionally observed during HD. A decline in CD11c surface density paralleled the sequestration of CD14+CD16+ monocytes. Basal surface densities of important adhesion receptors differed significantly between the CD14+CD16+ and CD14++ subsets. In conclusion, during HD the CD14+CD16+ subset revealed different sequestration kinetics, with a more pronounced and longer disappearance from the blood circulation, compared with CD14++ monocytes. This sequestration kinetics may be due to a distinct surface expression of major adhesion receptors which facilitate leucocyte–leucocyte, as well as leucocyte–endothelial, interactions.

Keywords: monocytes, CD14+CD16+ subset, haemodialysis, monocytopenia, sequestration

Introduction

Since the early observation of a transient leukopenia in the first minutes of heamodialysis (HD) by Kaplow and Goffinet [1], this issue has undergone extensive investigation. Several studies have shown that neutropenia and monocytopenia take place during HD procedures when cellulosic membranes are used [2–5]. Leucocyte margination and adhesion is associated with complement activation during HD with cellulosic dialysers such as cuprophan [6]. During the HD process, direct contact of plasma with the dialyser membrane initiates the alternative pathway of complement activation leading to the generation of the active peptides C3a and C5a which can then induce responses in neutrophils [6,7]. However, synthetic membranes that show a higher biocompatibility (e.g. polyamide, polyacrylonitrile or polysulphone) markedly reduced complement and granulocyte activation, as well as subsequent granulocytopenia [3,7–9].

Most studies have focused on the pathophysiology of granulocytes during HD. However, the HD process also influences monocytes. In addition, monocytes also express many of the same complement and adhesion receptors expressed by neutrophils (e.g. CD11b, CD11c, etc.). It has been suggested that neutrophils and monocytes are activated during dialysis even before they pass the dialyser [5].

Peripheral blood monocytes are not a homogeneous population and can be subdivided into discrete subpopulations by virtue of their surface antigen expression. A minor subset of circulating monocytes express the Fcγ receptor III (CD16) together with lower levels of the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) receptor antigen (CD14) [10]. These cells are described as the CD14+CD16+ monocyte subpopulation [11]. The majority of blood monocytes express high levels of CD14 (CD14++ monocytes) and are negative for CD16. In normal healthy subjects the CD14+CD16+ subset accounts for about 7–10% of all circulating blood monocytes [12–15]. However, during infectious or inflammatory diseases, such as AIDS [13,16], septicaemia [17], tuberculosis [18] or asthma [19], CD14+CD16+ monocyte numbers are markedly expanded. Recently we reported that elevated monocyte counts in stable HD patients resulted from an expansion of the CD14+CD16+ subpopulation [14]. While numbers of CD14+ CD16+ monocytes were significantly higher, counts of CD14++ monocytes were unaltered compared with normal controls.

CD14+CD16+ monocytes are thought to act as an important proinflammatory effector monocyte subset based upon their expansion during inflammatory processes [11,20]. Their cytokine expression is primarily proinflammatory, while expression of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 is low compared with that seen in CD14++ monocytes [21]. In addition, CD14+CD16+ monocytes show a distinct scavenger receptor function [22] and possess properties of tissue macrophages [11,12].

The aim of the present study was to examine the sequestration kinetics of the CD14+CD16+ and CD14++ monocyte subsets during haemodialysis, and to analyse variations in adhesion receptor expression during the disappearance and return of this leucocyte subpopulation into the peripheral circulation. In addition, we compared the cell surface density of various adhesion receptors responsible for leucocyte–endothelial, as well as leucocyte–leucocyte interactions, in both monocyte subpopulations.

Patients and methods

Study population

Eleven patients on chronic maintenance haemodialysis were selected for the study. Informed consent was obtained from the patients for additional blood sampling. The patients had been on haemodialysis for 1–15 years. All dialyses were part of the routine dialysis programme for each patient. None of the patients had clinical evidence of acute infections or inflammatory diseases at the time of the study. Seventeen healthy subjects from our clinical and laboratory staff were recruited as normal controls.

Haemodialysis

Patients studied underwent 4 h of maintenance haemodialysis three times per week. Patients received medication including erythropoietin, phosphate binders, multivitamins, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II antagonists and/or calcium antagonists. None received drugs known to interfere with the immunoresponse at the time of the study. All patients were placed on a normocaloric diet and low water and potassium intake. Eight patients were routinely dialysed with a polyamide membrane (Polyflux 11; Gambro, Hechingen, Germany) and three with a polysulphone membrane (Hemoflow F-60S, Fresenius, Bad Homburg; and APS-650, Diamed, Köln, Germany). Water produced by reverse osmosis and concentrate was distributed by distinct loops. The routinely used dialysate contained bicarbonate (32·5 mmol/l). Blood flow ranged from 180 to 300 ml/min. Anticoagulation was performed using a heparin bolus (1500–2500 IE) followed by continuous heparin administration (500–1000 IE/h).

Blood samples and cell counts

Blood samples were drawn before the haemodialysis session and from the arterial line at 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120, 180 and 240 min after starting HD. Additionally, in selected patients blood specimens were collected 2–18 h after the end of HD. The samples were collected in sterile tubes containing K-EDTA (1·5 mg/ml blood) as an anticoagulant.

Leucocyte counts, as well as differential counts for lymphocytes, monocytes and neutrophils, were determined using a blood cell analyser (Coulter STKS; Krefeld, Germany).

Flow cytometric analyses and monoclonal antibodies

Leucocytes were analysed by two- or three-colour immunostaining of whole blood. The characteristics of the MoAbs used in this study are listed in Table 1. For direct immunofluorescence labelling, 100 μl of whole blood were incubated with antigen-specific fluorochrom-labelled MoAbs or the corresponding isotype control antibodies for 15 min at room temperature. The erythrocytes were lysed for 10 min with specific lysis solution (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany). After washing with PBS, the leucocytes were fixed with 0·5 ml of 2% paraformaldehyde. Fixed cells were analysed by flow cytometry within 6 h.

Table 1.

Specificity of monoclonal antibodies used in the study

| MoAb | Antigen | Clone | Label | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD11a | LFA-1 | G-25.2 | FITC | BD |

| CD11b | MAC-1, complement receptor 3 | D12 | PE | BD |

| CD11c | p150,95 | S-HCL-3 | PE | BD |

| CD14 | LPS receptor | MΦP9 | PerCP | BD |

| CD16 | Fcγ receptor type III | G022 | PE | BD |

| 3G8 | FITC | Immunotech | ||

| CD18 | β2-integrin | L130 | FITC | BD |

| CD29 | VLA-β | K20 | FITC | Immunotech |

| CD31 | PECAM-1 | WM59 | FITC | PharMingen |

| CD35 | Complement receptor 1 (CR1) | E11 | FITC | PharMingen |

| CD44 | pgp-1 | J.173 | FITC | Immunotech |

| CD49d | VLA-4 | HP2/1 | FITC | Immunotech |

| CD50 | ICAM-3 | HP2/19 | PE | Immunotech |

| CD54 | ICAM-1 | LB-2 | PE | BD |

| CD62L | l-selectin | DREG56 | FITC | Immunotech |

| CD102 | ICAM-2 | CBR-IC2/2 | FITC | Bender Diagnostics |

Sources: BD, Becton Dickinson; PharMingen, Becton Dickinson-PharMingen product line; Immunotech: product line of Beckman-Coulter.

Monocytes were gated based upon their light scattering properties and then FITC, PE and PerCP channel fluorescence was recorded within the monocyte gate for specific, as well as non-specific, labelling. Results were expressed as mean channel fluorescence intensity (MFI) of specific minus non-specific staining.

Statistical analysis

Results were normally expressed as mean ± s.d. for each value. For statistical analysis the mathematical software BIAS version 5.0 (obtained from Dr Hans Ackermann, Department of Biomathematics, University of Frankfurt/Main, Germany) was used. Statistical comparisons between different parameters were performed using Student's t-test or the Wilcoxon matched pairs test as appropriate. P < 0·05 was considered significant.

Results

Granulocyte and monocyte cell count during haemodialysis

We initially compared leucocyte numbers in 11 patients during haemodialysis with synthetic polyamide or polysulphone membranes. Leucocyte counts were examined before dialysis (t0), at close intervals during dialysis (t15min – t180min) and at the end of the dialysis session (t240min). The granulocyte and monocyte responses to dialysis are shown in Table 2. The neutrophil count was found to be slightly decreased at the beginning of HD, but the changes were significant only at 15 min. In contrast, a significant decrease in the number of peripheral blood monocytes occurred between 15 and 30 min of dialysis. Although not statistically significant, the mean monocyte count remained suppressed during dialysis. Monocyte, as well as neutrophil, counts varied up to three-fold between individual patients (predialysis levels: 335–1035 monocytes/μl; 2520–8436 neutrophils/μl). Therefore the percentage variation in cell numbers during a HD session, compared with the predialysis level, was calculated for further studies.

Table 2.

Neutrophil and monocyte counts before and during dialysis

| Time of dialysis | Neutrophils (cells/μl) | Monocytes (cells/μl) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 (pre) | 5253 ± 1997 | 520 ± 242 |

| 15 min | 4472 ± 2023* | 379 ± 129* |

| 30 min | 4939 ± 2408 | 410 ± 172* |

| 45 min | 5142 ± 2334 | 457 ± 185 |

| 60 min | 5059 ± 2379 | 468 ± 194 |

| 90 min | 5186 ± 2327 | 465 ± 188 |

| 120 min | 5251 ± 2007 | 472 ± 181 |

| 180 min | 5344 ± 2390 | 462 ± 170 |

| 240 min | 5215 ± 2103 | 467 ± 174 |

Whole blood specimens were collected before (pre) a haemodialysis (HD) session, at the indicated time intervals during HD and at the end (240 min). Peripheral blood neutrophils and monocytes were counted using an automated blood cell counter. Data are mean ± s.d. from 11 patients using biocompatible synthetic dialyser membranes.

P < 0·05 versus predialysis (t0).

Differential kinetics of CD14++ and CD14+CD16+ monocyte subsets during haemodialysis

The intradialytic changes in neutrophil, as well as monocyte subset, numbers were examined as described above. Neutrophil counts were slightly reduced only in the initial phase of HD (t15: 83 ± 13%, P < 0·05) and returned to basal levels 30–45 min after the onset of HD (t30: 88 ± 10%; t45: 94 ± 11%; Fig. 1). When peripheral blood monocytes were examined by two-colour CD14/CD16 immunofluorescence, substantial differences between the CD14++ and CD14+CD16+ subpopulations were observed (Fig. 2).

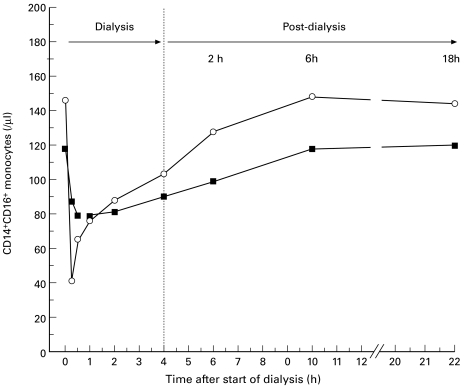

Fig. 1.

Changes in peripheral blood neutrophil and CD14++ and CD14+CD16+ monocyte subset numbers during haemodialysis. Data are from 11 patients dialysed with biocompatible polyamide or polysulphone membranes. Values are shown as the percentage of the level before dialysis. ▪, Neutrophils; ○, CD14++ monocytes; •, CD14+CD16+ monocytes.

Fig. 2.

Two-colour CD14/CD16 immunostaining of peripheral blood monocytes during haemodialysis (HD). Peripheral blood specimens were stained with an anti CD14–FITC and an anti-CD16–PE-labelled antibody. Cells were further analysed by flow cytometry as described (see PATIENTS and METHODS). Results of a representative patient before HD (a), after 30 min of HD (b), and at the end of HD (c) are shown. The percentage of CD14+CD16+ monocytes (upper right quadrant) is 23% (a), 9% (b) and 17% (c).

As shown in Fig. 1, the kinetics of CD14++ monocyte levels paralleled that of neutrophils, except for a slightly more pronounced decline at start of HD (t15: 77 ± 13%, P < 0·01; t30: 81 ± 15%, P < 0·05). In contrast, the CD14+CD16+ monocyte subset dropped dramatically to 33 ± 15%, P < 0·001, during the first 30 min of dialysis and only began to recover slowly during ongoing HD (t60: 55 ± 16%; t90: 48 ± 15%; and t120: 58 ± 12%). CD14+CD16+ cell numbers remained suppressed until the end of dialysis (t240: 67 ± 11%, P < 0·05).

Since the CD14+CD16+ monocyte subset remained suppressed until the end of the dialysis sessions, we examined this subset in the intradialytic time period. The number of CD14+CD16+ monocytes was measured during a HD session, as well as up to 18 h after HD. Figure 3 shows the results of two out of four patients tested. The return of CD14+CD16+ monocytes into the circulation started during ongoing HD, as described above, and was completed at about 6 h after the end of HD.

Fig. 3.

Changes in the CD14+CD16+ monocyte subpopulations in two patients during and after haemodialysis. Numbers of the CD14+CD16+ blood monocytes were calculated before and during a 4-h dialysis session, as well as up to 18 h after the end of dialysis. One patient used a polyamide membrane (▪) and the other patient a polysulphone dialyser (○).

Rebound monocytosis of CD14++ but not CD14+CD16+ monocytes

CD14++ and CD14+CD16+ monocyte subpopulations also differed in their rebound kinetics during a HD session. While in most patients the CD14++ monocytes declined in the initial phase of dialysis and then subsequently returned to predialysis levels, in two patients a rebound monocytosis of these cells was observed.

The kinetics of CD14++ and CD14+CD16+ monocytes for both these patients is shown in Fig. 4. As described above, in these patients the CD14++ monocyte count and CD14+CD16+ monocyte count fell rapidly in the initial phase of dialysis and then started to rise during ongoing dialysis. However, as CD14++ monocytes returned into circulation, a transient (patient A) or continuous CD14++ monocytosis (patient B) during HD was observed. In patient A, CD14++ monocyte numbers reached a peak level of 130% of the predialysis level at 90 min, and returned to basal levels at the end of the session. In the other patient, CD14++ monocyte counts rose to 121% of the predialysis level and remained elevated throughout the session. In contrast, after the initial drop, the CD14+CD16+ subset slowly increased to 57% or 73% of the predialysis level in patient A and B, respectively. Thus, CD14+CD16+ monocytes did not follow the rebound monocytosis observed occasionally for CD14++ monocytes.

Fig. 4.

Rebound monocytosis in two patients (A and B) during haemodialysis. Absolute cell numbers, as well as percentage changes compared with predialysis levels, are shown for CD14++ (•) and CD14+CD16+ (○) monocytes.

Adhesion receptor expression of CD14++ and CD14+CD16+ monocytes in HD patients and healthy controls

We compared the cell surface expression of 13 adhesion and complement receptor molecules expressed on the surface CD14++ and CD14+CD16+ monocytes in haemodialysed patients and healthy controls (Table 3). The CD14+CD16+ monocyte subset revealed a unique expression pattern of surface receptor molecules compared with the CD14++ population. Of the 13 antigens measured only CD44 and CD29 were of equal surface density in both monocyte populations, whereas expression of seven antigens (CD11a, CD11c, CD18, CD31, CD49d, CD54 and CD102) were significantly higher in CD14+CD16+ monocytes. The surface density of four antigens (CD11b, CD35, CD50 and CD62L) were lower in the CD14+CD16+ subset.

Table 3.

Comparison of antigen expression between peripheral blood monocyte (PBM) subsets

| PBM from healthy controls (n = 17) | PBM from HD patients (n = 14) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antigen | CD14++ | CD14+CD16+ | CD14++ | CD14+CD16+ |

| CD11a | 64 ± 9 | 130 ± 14* | 65 ± 10 | 140 ± 24* |

| CD11b | 386 ± 90 | 291 ± 52* | 335 ± 76 | 254 ± 65* |

| CD11c | 378 ± 65 | 934 ± 97* | 288 ± 67 | 940 ± 171* |

| CD18 | 127 ± 38 | 238 ± 29* | 114 ± 19 | 212 ± 37* |

| CD29 | 140 ± 17 | 136 ± 19 | ND | ND |

| CD31 | 136 ± 16 | 290 ± 52* | 165 ± 22 | 326 ± 63* |

| CD35 | 33 ± 6 | 15 ± 4* | 27 ± 11 | 12 ± 3* |

| CD44 | 1252 ± 132 | 1209 ± 190 | ND | ND |

| CD49d | 45 ± 9 | 108 ± 13* | 51 ± 11 | 116 ± 21* |

| CD50 | 2035 ± 355 | 1433 ± 300* | 1633 ± 319† | 1014 ± 266*† |

| CD54 | 89 ± 30 | 207 ± 63* | 69 ± 28 | 180 ± 47* |

| CD62L | 138 ± 27 | 26 ± 11* | 107 ± 44 | 10 ± 5* |

| CD102 | 43 ± 7 | 84 ± 12* | ND | ND |

PBM from healthy volunteers and haemodialysis (HD) patients were stained with specific MoAbs and analysed by three-colour immunofluorescence. Results are given as mean ± s.d. MFI of specific antigen expression.

P < 0·05 as significance in comparative analyses between CD14+CD16+ monocytes and CD14++ monocytes.

P < 0·05 in comparative analyses of a monocyte subset in HD patients versus healthy controls.

ND, Not determined.

Intradialytic expression of membrane adhesion antigens in CD14++ and CD14+CD16+ monocyte subsets

To investigate possible correlations between adhesion receptor expression and the sequestration kinetics for the monocyte subsets, the expression of several adhesion molecules on both CD14++ and CD14+CD16+ monocyte subpopulations was studied during haemodialysis. No significant changes were found in the cell surface density of β2-integrin molecules (CD11a, CD11b, CD11c) and the PECAM antigen (CD31) on CD14++ monocytes during HD. However, a slight but significant decline in the expression of CD11c was observed on the CD14+CD16+ subset during the first 30 min of HD; t0 908 ± 169 MFI, t15 778 ± 180 MFI (P < 0·05); t30 772 ± 182 MFI (P < 0·05). During the further course of HD, CD11c surface density levels increased to those of predialysis levels. A similar decrease in CD11a surface density was observed during sequestration of the CD14+CD16+ subset, but these changes were not considered to be statistically significant. Other antigens, including CD11b or CD49d, showed no alterations in either CD14++ or CD14+CD16+ monocyte numbers during HD (data not shown).

Discussion

Alterations in the immunocompetence of patients on chronic HD has been intensively investigated during the last decade (reviewed by Descamps-Latscha [23]). These changes in cellular immunity result partly from the uraemic state, as well as from renal replacement therapy. Studies of the functional capacity of immune cells have revealed a paradoxical association between cell activation and an aberrantly reduced response to specific stimulations [24].

While older studies have examined granulocyte and lymphocyte immunology, little attention was paid to peripheral blood monocytes in haemodialysed patients (reviewed by Gibbons et al. [25]). However, during the past few years more work has focused on the changes in monocyte function, e.g. scavenger receptor activity [26] and cytokine expression and release [28–30].

Peripheral blood monocytes are not homogeneous with regard to their cell surface receptor expression. Using the Fcγ receptor III (CD16) and LPS receptor (CD14) as marker antigens, the majority of circulating monocytes in healthy controls exhibit the CD14++ phenotype and ≤ 10% belong to the CD14+CD16+ subpopulation. CD14+CD16+ monocytes are potent proinflammatory cells that expand during various infectious and inflammatory conditions [11]. In addition, expanded CD14+CD16+ monocyte populations are also seen in stable patients undergoing chronic HD. Patients with acute or chronic inflammatory diseases exhibit a further elevation of this cell population [14].

The HD procedure is associated with leucocyte activation during the extracorporeal blood circuit. The contact of blood components with the dialyser membrane triggers monocytes to release proinflammatory cytokines by the combined action of complement activation, leucocyte adherence and stimulatory dialysate components, such as endotoxin (reviewed by Chatenoud et al. [24]). In the present study, we found different sequestration kinetics for the CD14+CD16+ subset compared with CD14++ monocytes. While minor sequestration of CD14++ monocytes was noted only in the early 30 min of the haemodialysis sessions, the CD14+CD16+ subpopulation was more markedly suppressed in the peripheral circulation and the suppression was longer lived than that seen for the CD14++ monocytes. This intense margination could not be explained solely by complement activation, as synthetic polyamide or polysulphone membranes do not induce significant complement activation compared with cellulosic membranes [5,7,9]. We observed no significant changes in monocyte CD11b expression during HD in either monocyte populations. In addition, CD14+CD16+ monocytes are thought to be less sensitive to complement activation than CD14++ monocytes due to their lower expression of complement receptors CR3 (CD11b/CD18) and CR1 (CD35). In relation to this, a model has been proposed suggesting that both receptors co-operate in the binding of complement-opsonized particles [31].

The intense sequestration of CD14+CD16+ cells seen here implicates a tight adherence onto capillary endothelia analogous to that proposed for neutrophil sequestration [32]. While in earlier reports leucocyte adherence was thought to be mediated primarily by the CD11b/CD18 receptor [33], additional adhesion molecules may also be involved. We found that CD14+CD16+ monocytes reveal distinct surface densities of important adhesion molecules that are clearly different from the spectrum of expression seen in the CD14++ population. This expression pattern may play a role in the altered sequestration kinetics described here. For example, PECAM-1 is required for the transendothelial migration of leucocytes [34] and is capable of participating in an adhesion cascade resulting in the activation of monocyte β2-surface integrins [35]. Therefore, a higher PECAM expression on CD14+CD16+ cells may support their adherence to vascular endothelia. The unique expression of adhesion molecules by the CD14+CD16+ subset favours the hypothesis that, following activation, cells with a unique expression pattern may ‘sequester’ more intensively than other cell populations. This may explain the decline of adhesion receptor densities, such as CD11c, seen on those CD14+CD16+ cells that remain in the circulation during the margination phase.

In 1998 Steppich et al. postulated a model of monocyte compartmentalization between a marginal and central pool [36]. Therein, CD14+CD16+ monocytes interact more avidly with the vascular endothelium. This could lead to a preferential localization of these cells to the marginal pool. Additionally, CD14+CD16+ monocytes are mobilized by physical stress and a catecholamine-dependent mechanism from the marginal into the central pool [37]. Arnaout et al. [33] hypothesized that during HD endocrinological alterations, such as alterations in endogenous glucocorticoid or catecholamine levels, may alter granulocyte adhesiveness in vivo. To date this has not been reported for monocytes. However, we and others have reported a selective and reversible suppression of CD14+CD16+ monocytes after administration of glucocorticoids [20,38].

If the expanded CD14+CD16+ subset (seen even in stable HD patients [14]) results from chronic activation during the dialysis procedure, the repeated sequestration, as well as the recovery cycles that take place during long-term HD, may lead to an enhanced overall level of these cells in HD patients. Alternatively, the increased CD14+CD16+ monocyte numbers could also represent a latent inflammatory response to the uraemic situation in HD patients. This hypothesis is strengthened by our recent findings of elevated CD14+CD16+ subsets in uraemic patients using chronic peritoneal dialysis for renal replacement therapy [39].

In conclusion, during HD the CD14+CD16+ monocyte subpopulation showed increased and longer margination from the blood circulation compared with CD14++ monocytes. Several immunomodulatory events that take place during the extracorporeal blood circuit may initiate monocyte sequestration. In a similar manner, during cardiopulmonary bypass the percentage of CD14+CD16+ monocytes in circulation is also decreased [40]. Thus, more intense studies of these cells would clarify the underlying mechanisms of leucocyte activation, as well as deactivation, during extracorporeal blood circuits.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Angelika Nockher for her excellent technical assistance during the study and Dr Peter Nelson for critically reading the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kaplow LS, Goffinet JA. Profound neutropenia during the early phase of hemodialysis. JAMA. 1968;203:1135–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Craddock PR, Freh J, Dalmasso AP, Brigham KL, Jacobs HS. Hemodialysis leukopenia: pulmonary vascular leukostasis resulting from complement activation by dialyzer cellophane membranes. J Clin Invest. 1977;59:879–88. doi: 10.1172/JCI108710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stuard S, Carreno M-P, Poignet J-L, Albertazzi A, Haeffner-Cavaillon N. A major role for CD62P/CD15s interaction in leukocyte margination during hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 1995;48:93–102. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaupke CJ, Zhang J, Cesario T, Yousefi S, Akeel N, Vaziri ND. Effect of hemodialysis on leukocyte adhesion receptor expression. Am J Kidney Dis. 1996;27:244–52. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(96)90548-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tabor B, Geissler B, Odell R, Schmidt B, Blumenstein M, Schindhelm K. Dialysis neutropenia. The role of the cytoskeleton. Kidney Int. 1998;53:783–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hakim RM. Clinical implications of hemodialysis membrane biocompatibility. Kidney Int. 1993;44:484–94. doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Combe C, Pourtein M, de Precigout V, et al. Granulocyte activation and adhesion molecules during hemodialysis with cuprophane and a high-flux biocompatible membrane. Am J Kidney Dis. 1994;24:437–42. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80900-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alvarez V, Pulido R, Campanero M, de Paraiso V, Landazuri MO, Sanchez-Madrid F. Differentially regulated cell surface expression of leukocyte adhesion receptors on neutrophils. Kidney Int. 1991;40:899–905. doi: 10.1038/ki.1991.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawabata K, Nagake Y, Shikata K, Makino H, Ota Z. The changes of Mac-1 and l-selectin expression on granulocytes and soluble l-selectin level during hemodialysis. Nephron. 1996;73:573–9. doi: 10.1159/000189143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Passlick B, Flieger D, Ziegler-Heitbrock HWL. Identification and characterization of a novel monocyte subpopulation in human peripheral blood. Blood. 1989;74:2527–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ziegler-Heitbrock HWL. Heterogeneity of human blood monocytes: the CD14+CD16+ subpopulation. Immunol Today. 1996;17:424–8. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)10029-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ziegler-Heitbrock HWL, Fingerle G, Ströbel M, Schraut W, Stelter F, Schüttc Passlick B, Pforte A. The novel subset of CD14+/CD16+ blood monocytes exhibit features of tissue macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:2053–8. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nockher WA, Bergmann L, Scherberich JE. Increased soluble CD14 serum levels and altered CD14 expression of peripheral blood monocytes in HIV-infected patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994;98:369–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb05499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nockher WA, Scherberich JE. Expanded CD14+CD16+ monocyte subpopulation in patients with acute and chronic infections undergoing hemodialysis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2782–90. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2782-2790.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanaka M, Honda J, Imamura Y, Shiraishi K, Tanaka K, Oizumi K. Surface phenotype analysis of CD16+ monocytes from leukapheresis collections for peripheral blood progenitors. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;116:57–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00869.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thieblemont N, Weiss L, Sadeghi HM, Estcourt C, Haeffner-Cavaillon N. CD14lowCD16high: a cytokine-producing monocyte subset which expands during human immunodeficiency virus infection. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:3418–24. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830251232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fingerle G, Pforte A, Passlick B, Blumenstein M, Ströbel M, Ziegler-Heitbrock HWL. The novel subset of CD14+/CD16+ blood monocytes is expanded in sepsis patients. Blood. 1993;82:3170–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vanham G, Edmonds K, Qing L, et al. Generalized immune activation in pulmonary tuberculosis: co-activation with HIV infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;103:30–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.907600.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rivier A, Pene J, Rabesandratana H, Chanez P, Bousquet J, Campbell AM. Blood monocytes of untreated asthmatics exhibit some features of tissue macrophages. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;100:314–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb03670.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scherberich JE, Nockher WA. CD14++ monocytes, CD14+/CD16+ subset and soluble CD14 as biological markers of inflammatory systemic diseases and monitoring immunosuppressive therapy. Clin Chem Lab Med. 1999;37:209–13. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.1999.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frankenberger M, Sternsdorf T, Pechumer H, Pforte A, Ziegler-Heitbrock HWL. Differential cytokine expression in human blood monocyte subpopulations: a polymerase chain reaction analysis. Blood. 1996;87:373–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Draude G, von Hundelshausen P, Frankenberger M, Ziegler-Heitbrock HW, Weber C. Distinct scavenger receptor expression and function in the human CD14+CD16+ monocyte subset. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:H1144–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.4.H1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Descamps-Latscha B, Herbelin A. Long-term dialysis and cellular immunity: a critical survey. Kidney Int. 1993;43(Suppl. 41):S135–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chatenoud L, Jungers P, Descamps-Latscha B. Immunological considerations of the uremic and dialyzed patient. Kidney Int. 1994;45(Suppl 44):S92–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gibbons RAS, Martinez OM, Garovoy MR. Altered monocyte function in uremia. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1990;56:66–80. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(90)90170-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ando M, Lundkvist I, Bergstrom J, Lindholm B. Enhanced scavenger receptor expression in monocyte-macrophages in dialysis patients. Kidney Int. 1996;49:773–80. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thylen P, Fernvik E, Haegerstrand A, Lundahl J, Jacobson SH. Dialysis-induced serum factors inhibit adherence of monocytes and granulocytes to adult human endothelial cells. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;29:78–85. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mege JL, Capo C, Purgus R, Olmer M. Monocyte production of transforming growth factor beta in long-term hemodialysis: modulation by hemodialysis membranes. Am J Kidney Dis. 1996;28:395–9. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(96)90497-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Girndt M, Sester U, Kaul H, Köhler H. Production of proinflammatory and regulatory monokines in hemodialysis patients shown at a single-cell level. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9:1689–96. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V991689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balakrishnan VS, Jaber BL, Natov SN, Cendoroglo M, King AJ, Schmid CH, Pereira BJ. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist synthesis by peripheral blood mononuclear cells in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 1998;54:2106–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sutterwala FS, Rosenthal LA, Mosser DM. Cooperation between CR1 (CD35) and CR3 (CD11b/CD18) in the binding of complement-opsonized particles. J Leuk Biol. 1996;59:883–90. doi: 10.1002/jlb.59.6.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toren M, Goffinet JA, Kaplow LS. Pulmonary bed sequestration of neutrophils during hemodialysis. Blood. 1970;36:337–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arnaout MA, Hakim R, Todd RF, Dana N, Colten HR. Increased expression of an adhesion-promoting surface glycoprotein in the granulocytopenia of hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:457–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198502213120801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muller WA, Weigl SA, Deng X, Phillips DM. PECAM-1 is required for transendothelial migration of leukocytes. J Exp Med. 1993;178:449–60. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.2.449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berman ME, Muller WA. Ligation of platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 (PECAM-1/CD31) on monocytes and neutrophils increases binding capacity of leukocyte CR3 (CD11b/CD18) J Immunol. 1995;154:299–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steppich B, Ziegler-Heitbrock HWL. Preferential localization of CD14+CD16+ monocytes in the marginal pool. Immunobiology. 1998;199:555. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steppich B, Dayyani F, Gruber R, Lorenz R, Mack M, Ziegler-Heitbrock HWL. Selective mobilization of CD14+CD16+ monocytes by exercise. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;279:C578–86. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.3.C578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fingerle-Rowson G, Angstwurm M, Andreesen R, Ziegler-Heitbrock HWL. Selective depletion of CD14+CD16+ monocytes by glucocorticoid therapy. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;112:501–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00617.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scherberich JE, Nockher WA. Blood monocyte phenotypes and soluble endotoxin receptor CD14 in systemic inflammatory diseases and in patients with chronic renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000;15:574–8. doi: 10.1093/ndt/15.5.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hiesmayr MJ, Splitter A, Lassnigg A, et al. Alterations in the number of circulating leucocytes, phenotype of monocyte and cytokine production in patients undergoing cardiothoracic surgery. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;115:314–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00801.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]