Abstract

Platelet-activating factor (PAF) is a proinflammatory agent in infectious and inflammatory diseases, partly due to the activation of infiltrating phagocytes. PAF exerts its actions after binding to a monospecific PAF receptor (PAFR). The potent bioactivity is reflected by its ability to activate neutrophils at picomolar concentrations, as defined by changes in levels of intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i), and induction of chemotaxis and actin polymerization at nanomolar concentration. The role of PAF in neutrophil survival is, however, less well appreciated.

In this study, the inhibitory effects of synthetic PAFR-antagonists on various neutrophil functions were compared with the effect of recombinant human plasma-derived PAF-acetylhydrolase (rPAF-AH), as an important enzyme for PAF degradation in blood and extracellular fluids. We found that endogenously produced PAF (–like) substances were involved in the spontaneous apoptosis of neutrophils. At concentrations of 8 µg/ml or higher than normal plasma levels, rPAF-AH prevented spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis (21 ± 4% of surviving cells (mean ± SD; control) versus 62 ± 12% of surviving cells (mean ± SD; rPAF-AH 20 µg/ml); P < 0·01), during overnight cultures of 15 h. This effect depended on intact enzymatic activity of rPAF-AH and was not due to the resulting product lyso-PAF. The anti-inflammatory activity of rPAF-AH toward neutrophils was substantiated by its inhibition of PAF-induced chemotaxis and changes in [Ca2+]i.

In conclusion, the efficient and stable enzymatic activity of rPAF-AH over so many hours of coculture with neutrophils demonstrates the potential for its use in the many inflammatory processes in which PAF (–like) substances are believed to be involved.

Keywords: neutrophils, platelet-activating factor acetyl hydrolase, chemotaxis, apoptosis, inflammation

INTRODUCTION

Platelet-activating factor (PAF) (1-O-alkyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine) is a potent phospholipid mediator with pleiotropic effects on a variety of cells and tissues [1,2]. PAF has various pathophysiological effects on the cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal and central nervous system. In addition to these effects, PAF is a key agent in the pathogenesis of inflammatory processes through its ability to activate neutrophilic granulocytes [1–3]. PAF mediates its bioactivity by the activation of a specific G-protein-coupled, seven-transmembrane receptor, the PAFR [4–6]. Two forms of human PAFR transcripts exist with identical open reading frames driven by individual promotors and regulation: transcript 1 is expressed in a ubiquitous fashion and is most abundant in leucocytes, and transcript 2 is mainly located in heart, lung, spleen and kidney but not in brain and leucocytes [7,8].

An acute inflammatory response consists of a directed influx of neutrophilic granulocytes as the first line of defense. Many granulocytic functions, such as those required for extravasation [9,10], and responsive signalling cascades can be induced by PAF, but not all [11]. Neutrophils can be stimulated to a brisk response of chemotaxis, actin polymerization, some adhesion and degranulation, but PAF cannot activate the NADPH oxidase system by itself. On the other hand, PAF ‘primes’ the neutrophils to respond to a second stimulus, such as the bacterial peptide analogue FMLP, with a strongly increased generation of toxic oxidative products [12].

After the influx of granulocytes into extravascular tissues, these cells exert antimicrobial protection until they go into apoptosis and are subsequently taken up by tissue macrophages. These mechanisms have been proposed for the removal of neutrophils from daily turnover in the tissues as well as at sites of inflammation. The mechanisms involved in regulating neutrophil survival are poorly understood, but there is evidence that growth factors (e.g. G(M)-CSF) and cytokines (e.g. TNF-α and IL-1) can alter the rate of the neutophil apoptosis in vitro [13–15]. Although the involvement of PAF in these apoptotic reactions has been suggested [16], its precise contribution remained controversial.

PAF may be derived from the tissue cells involved in the inflammatory process, such as macrophages and endothelial cells, as well as from the infiltrating neutrophils. The potency and nature of its effect suggest that both its synthesis and breakdown must be strictly controled [1,2]. Degradation plays a major role in the potential for PAF to circulate or function as a local autocoid. PAF is degraded by hydrolysis of the acetyl group at the sn-2 position of the glycerol backbone to produce the biologically inactive lyso-PAF and acetate. This process is catalysed by specific enzymes with so-called PAF-acetyl hydrolase (PAF-AH) activity [17]. Several PAF-AHs have been identified in the cytosol of tissue cells as well as in plasma, and were subsequently purified and cloned [18–20]. Plasma PAF-AH activity is a 45-kD protein unrelated to any known lipase or phospholipase, which is present in plasma or serum at levels of 0·5–1 µg/ml as a fully functional enzyme, usually associated with plasma lipoproteins [17,18]. At an inflammatory site, PAF-AH is made available by vascular leakage, as indicated by the anti-inflammatory potential of PAF-AH in animal models [18]. In contrast to the rapid distribution and clearance of PAFR-antagonists, PAF-AH can thus be assumed to be active for long periods of time and, in addition, it can be more specifically distributed to inflammatory sites. Moreover, the catalytic activity of PAF-AH toward its substrate is not limited to its soluble or micellar form but is also present when PAF is exposed on the plasma membrane of activated cells [17].

Except for PAF-induced neutrophil polarization, little is known about the effects of rPAF-AH on neutrophil functions [18]. We therefore undertook a study to investigate the effect of rPAF-AH on early and late neutrophil reponses in comparison with well-characterized PAFR-antagonists. The rPAF-AH proved to be a more potent antagonist than the PAFR-antagonists used in our study. It blocked PAF-induced neutrophil chemotaxis and changes in [Ca2+]i, as well as spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis. In this way, we established a possible role for endogenous PAF-like material in the normal turn-over of human neutrophils.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

PAF, lyso-PAF, FMLP, cytochalasin B (Cyto B), and phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA); indo-1/AM was obtained from Molecular Probes (Junction City, OR, USA). WEB-2086 was a kind gift of Dr H. Heuer (Boehringer, Ingelheim, Germany). These reagents were dissolved in dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) at 1000 times the final concentration, aliquoted under sterile conditions and stored at − 20°C. TCV-309 was obtained from Dr H. Fukase (Takeda Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan), dissolved in sterile PBS at a stock concentration of 100 mm, and held at 4°C protected from light. Human recombinant platelet-activating factor-acetyl hydrolase (rPAF-AH; 4 mg/ml; produced by E. coli, LPS-and pyrogen-free) and identically treated ‘vehicle’ as solvent controls to exclude contaminating bacterial products were a generous gift of Dr G. Dietsch (ICOS Corporation, Bothell, WA, USA) and kept at 4°C under sterile conditions. No contamination by LPS was measured by the Limulus-amoebocyte lysate assay (LAL assay; Kabi Pharmaceutical, Mölndal, Sweden). Serum-treated zymosan (STZ) was prepared according to Goldstein et al. [21]. FITC-labelled Annexin-V was purchased from Bender MedSystems (Vienna, Austria). Monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs) were directed against FcγRIII (CD16, CLB/FcR-gran1; CLB, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), L-selectin (CD62L, Leu8; Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA, USA), Mac1 (CD11b, 44a; Amererican Tissue Culture Collection, Rockville, MD, USA), or Fas antigen (CD95). In case of Fas antigen, CD95 MoAbs were used with pro-apoptotic (MoAb APO-1–3 from Alexis Biochemicals, San Diego, CA, USA) or antiapoptotic effect (Fas-2; CLB). Basal incubation medium for cell suspensions contained 20 mm Hepes, 132 mm NaCl, 1 mm MgSO4, 1 mm CaCl2, 6 mm KCl, 1·2 mm KH2PO4, 5·5 mm glucose and 0·5% (w/v), human serum albumin (HSA), pH 7·4.

Leucocyte isolation

Blood was obtained from healthy volunteers by venepuncture, and was anticoagulated with 0·4% (w/v) trisodium citrate (pH 7·4). Granulocytes were purified as described before [22], and were resuspended in incubation medium at a final concentration of 106 cells/ml. Purity of the granulocytes was more than 98%, with > 95% neutrophils. Patient cells were isolated in a similar way.

Neutrophil chemotaxis

Chemotaxis was measured in a 48-well microchemotaxis chamber (NeuroProbe, Cabin John, MD, USA) [23]. Two cellulose filters were placed between the upper and lower compartments: a lower stop filter (0·45-µm pore size; Millipore Corp. Bedford, MA, USA) and a migration filter on top (150-µm thick, 8-µm pore size; Sartorius GmbH, Göttingen, Germany). Before use, the filters were soaked in incubation medium. Chemoattractant or incubation medium was placed in the lower compartments. Purified neutrophils were prewarmed in incubation medium (2 × 106/ml) for 15 min at 37°C, and 25 µl of the cell suspension (5 × 104 neutrophils) was then added to the upper compartment. The chambers were incubated for 90 min at 37°C.

PAF and FMLP were diluted in incubation medium and used as chemoattractant at concentrations previously defined to be optimal in the assay: 10−7 M PAF and 10−8 M FMLP, respectively. In some experiments, rPAF-AH (or vehicle) was added for 15 min to chemoattractant-containing incubation medium; in others, the neutrophils were preincubated with saturating amounts of the PAFR-antagonists WEB-2086 or TCV-309 for 15 min at 37°C before addition of the cells to the upper compartment. After 90 min, the migration filter was removed, was fixed with butanol-ethanol (20/80%, v/v) for 10 min, and was stained with Weigert's solution (1 : 1 mixture of haematoxylin 1% in ethanol (v/v) and a 70-mm acidic FeCl3 solution). The filters were dehydrated with ethanol, and made transparent with xylene. The number of cells that had completely passed the 150-µm thick filter was determined with light microscopy in 10 high-power fields (at a magnification of 400) per filter. Spontaneous migration without chemoattractants consisted of 5–7 cells in 10 high-power fields per filter.

Measurement of oxygen consumption

Oxygen consumption of neutrophils was measured at 37°C with an oxygen electrode, as described before [24]. In case of ‘priming’ the respiratory burst of neutrophils, the priming agent (i.e. PAF at 1 µM for 3–5 min; or LPS from E. coli (Sigma) at 20 ng/ml for 30 min) was added to the neutrophil suspension (2 × 106/ml in incubation medium containing 0·5% human serum instead of albumin) while being continuously stirred at 37°C. After the period of priming, the agonist was added (i.e. FMLP at 1 µM, or STZ at 10 mg/ml). The results are expressed as the rate of O2 consumption obtained after activation of neutrophils.

Measurement of cytosolic free Ca2+

[Ca2+]i was measured as described before [25]. In short, prewarmed neutrophils (5 min at 37°C, 107 cells/ml in incubation medium) were incubated with 0·5 µM indo-1/AM for 30 min at 37°C. After two washes, the cells were resuspended at 2 × 106 cells/ml in incubation medium and kept at room temperature. Fluorescence measurements were performed at 37°C under continuous stirring in a spectrofluorometer (model RF-540; Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). Excitation and emission wavelengths were 340 nm and 390 nm, respectively. Calibration of indo-1 fluorescence was determined by saturation of trapped indo-1 with Ca2+ after permeabilization of the cells with digitonin (5 µM), followed by quenching with Mn2+ (0·5 mm) [26]. A Kd of 250 nm was used for the indo-1/Ca2+ complex for the calculation of [Ca2+]i [27].

Measurement of PAF

PAF was measured with a commercially available radioimmunoassay (New England Nuclear, Boston, MA, USA) [28], according to the instructions of the manufacturer. The amount of PAF was determined in samples of 800 µl from neutrophils (2 × 106/ml) in incubation medium at 30 min, 1, 2, 3, 6, and at 18 h after overnight culture with or without centrifugation of the cells or separation of medium from the cells. Cells were mixed with 3 ml of methanol/chloroform (2 : 1) with 2% (v/v) acetic acid added to the methanol. After separation of the phases with 1 ml of chloroform and 1 ml of H2O, the lower phase was stored at −70°C under nitrogen. The amounts of PAF in the samples were determined from a standard curve constructed with known amounts of PAF. Recovery of PAF during the whole procedure was more than 90%, with the detection limit at 50 pg. Samples to determine neutrophil apoptosis in these incubations were simultaneously prepared and measured by FACscan (see below).

Determination of apoptosis and surface antigen expression

Apoptosis was measured according to Homburg et al. [15], with slight modifications. In short, neutrophil (2 × 106/ml) were usually cultured overnight in ISCOVE's medium, supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), penicillin (100 U/ml; Gibco), streptomycin (100 µg/ml; Gibco), fungizone (2·5 µg/ml; Gibco), and glutamine (2 mm). Unless indicated otherwise, the usual culture time was 15 h in 24- or 96-well plates (NUNC Brand Products, Denmark), incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. After culture, neutrophils were collected and checked for recovery (> 85%, after 15 h) and nuclear morphology. After washing the (non)apoptotic cells in ice-cold incubation medium, cells were labelled with Annexin-V/FITC at a 1 : 500 dilution in Hepes/plus medium (i.e. incubation medium containing 2·5 mm Ca2+) for 30–45 min at 4°C. After two additional washes with ice-cold Hepes/plus medium, cells were kept at 4°C and PI (1 : 100) was added prior to flowcytometry. Viable cells (Annexin-V/FITCneg, PIneg) were distinguished from early apoptotic (Annexin-V/FITCpos, PIneg) and late apoptotic cells (Annexin-V/FITCpos,PIpos). The percentage of necrotic neutrophils (Annexin-V/FITCneg,PIpos) was always < 3% in each sample. The number of cells were analysed with a FACScan (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA). Data were collected from 10 000 cells per sample.

Statistical analysis

Student's t-test for paired observations (two-tailed) was used for statitistical analysis.

RESULTS

PAF-dependent neutrophil chemotaxis

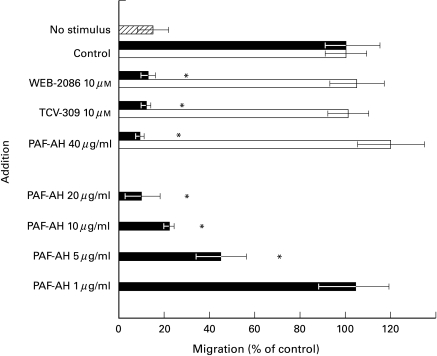

In a 48-well microassay, neutrophils were allowed to migrate for 90 min. As previously shown, the inhibitory effect of PAFR-antagonists such as WEB-2086 and TCV-309 was selective for the PAF-directed neutrophil mobility. In analogy with these PAFR-antagonists, coincubation of PAF with PAF-AH at 10–40 µg/ml in the lower chamber prevented the chemotactic response of neutrophils toward PAF but not toward FMLP. At lower concentrations, rPAF-AH became less effective (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Chemotaxis of neutrophils toward PAF and FMLP. Neutrophils (2 × 106/ml in incubation medium) were preincubated for 15 mins at 37°C before addition to the upper chamber. In some experiments, neutrophils were coincubated with the PAFR-antagonist WEB-2086, TVC-309, or DMSO as solvent control. Optimal concentration of chemoattractant was added to the lower chamber: PAF (10−7 M; ▪) or FMLP (10−8 M; □), and defined as 100%. Spontaneous chemokinesis is the condition with incubation medium without chemoattractant ( ). In some experiments, rPAF-AH was added in the indicated doses to the chemoattractants; the background chemokinesis without stimulus but with rPAF-AH remained unchanged. Mean ± SD of 3–5 experiments performed on different occasions. Significance (P < 0·05) is marked by an asterisk (*).

). In some experiments, rPAF-AH was added in the indicated doses to the chemoattractants; the background chemokinesis without stimulus but with rPAF-AH remained unchanged. Mean ± SD of 3–5 experiments performed on different occasions. Significance (P < 0·05) is marked by an asterisk (*).

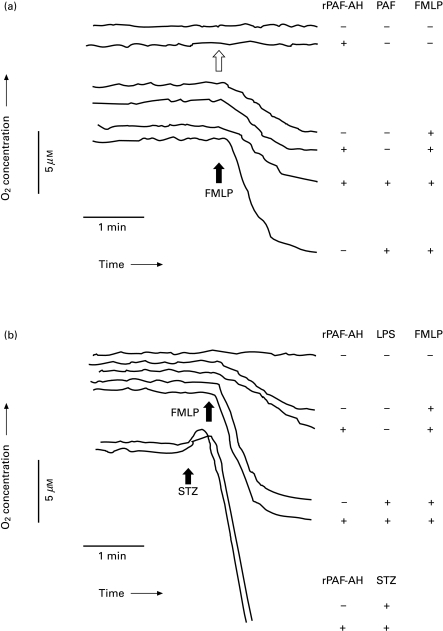

No involvement of endogenous PAF in the NADPH-oxidase activity

PAF is a well-characterized priming agent of FMLP-induced NADPH-oxidase activity of neutrophils [11]. This phenomenon of PAF priming was prevented by preincubation of the neutrophils with rPAF-AH at 40 µg/ml for 2–5 min prior to the addition of PAF up to 1 µM (Fig. 2a). The addition of rPAF-AH did neither result in neutrophil activation by itself (Fig. 2a; second trace, open arrow), nor in priming of the respiratory burst activity of the neutrophils upon activation with the agonist FMLP (Fig. 2a; fourth trace).

Fig. 2.

Activation of the respiratory burst in neutrophils. (a) In some experiments, cells were incubated with rPAF-AH (40 µg/ml) for 2–5 mins before FMLP was added (at 1 µm; black arrow). In other experiments, cells were preincubated by rPAF-AH before the primig agent PAF (at 1 µm for 3 min) was added, followed by FMLP (black arrow). In the second trace, rPAF-AH was added (open arrow) to show a lack of direct neutrophil activation in the absence of further additions. The order of additions is given in the Table corresponding to the traces. (b) In the experiments on LPS-priming effects, rPAF-AH (40 µg/ml) was added for 30 min or shortly before LPS (20 ng/ml, 30 min), until FMLP was added (at 1 µm; black arrow). STZ (at 10 mg/ml; black arrow) was used in the absence or presence of rPAF-AH (40 µg/ml, 2–5 min of preincubation). The order of additions is given in the Table corresponding to the traces. Experiments were performed on 3–5 different occasions.

In contrast to the effect on PAF priming, rPAF-AH did not prevent LPS-induced priming of the NADPH-oxidase activity upon FMLP addition (Fig. 2b). The lack of neutrophil priming when rPAF-AH was incubated over a longer period (up to 60 min) prior to the addition of FMLP, further excluded the presence of any contaminating LPS or other priming substances in the preparations of active rPAF-AH or the vehicle used (Fig. 2b; third trace for 30 min preincubation, and data not shown).

Neutrophils themselves are able to produce considerable amounts of PAF, in particular upon activation by serum-treated zymosan particles (STZ) particles. In comparison with STZ, activation with FMLP only results in nanomolar amounts of PAF generation, and only after pretreatment of the neutrophils with priming agents such as cytochalasin B, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), or the growth factor GM-CSF [29,30]. As shown in Fig. 2b, rPAF-AH was not able to change the kinetics of NADPH oxidase activity when STZ was used instead of FMLP, even when used at a lower concentration of particles (1 mg/ml; data not shown). The late start of endogenous PAF generation by neutrophils activated with FMLP or STZ may explain the apparent lack of effect of rPAF-AH on the NADPH-oxidase activity (Fig. 2a,b), as also found in case of the PAFR-antagonists WEB-2086 and TCV-309 [not shown].

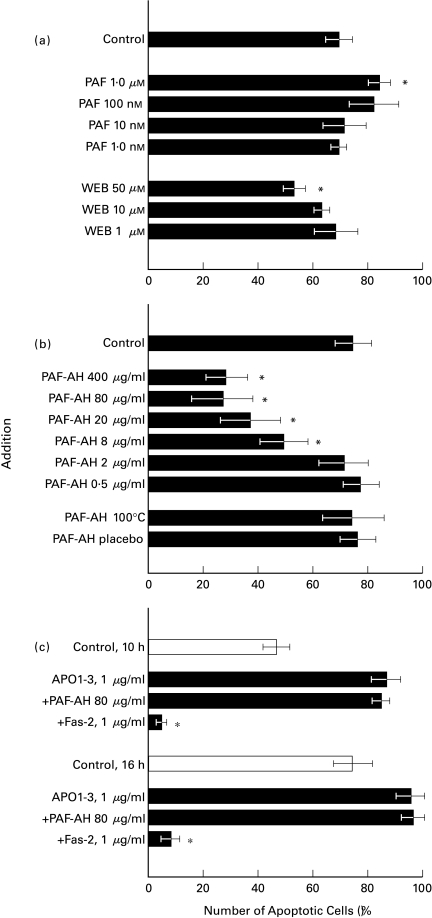

The effect of PAF on neutrophil survival

Although the amount of endogenously produced PAF seemed to be too little and too late to be relevant for most early neutrophil responses, the role of PAF or PAF-like substances in long-term neutrophil responses might be defined by the determination of cell survival during overnight cultures for 15 h. Upon addition of exogenous PAF, a small but significant increase in apoptosis was seen at high concentrations of PAF. PAFR-antagonists were able to rescue neutrophils from programmed cell death or apoptosis as shown here for WEB-2086 (Fig. 3a). At higher doses (>50 µm), this PAFR antagonist induced apoptosis instead of protection in neutrophils [not shown], most likely because WEB2086 can act as an agonist at higher concentrations. Instantaneous toxic effects of the PAFR antagonist were not detected (no LDH release or PI-staining within the first 5 h-tested) and seemed culture-dependent (significant increase in Annexin-V/FITC staining after > 12 h or more; data not shown). In contrast to the small effects observed with PAFR antagonists, rPAF-AH strongly prevented neutrophils from apoptosis (Fig. 3b). Direct interference of rPAF-AH with annexin-V/FITC binding to phosphatidyl serine lipids was excluded. First, the increment in neutrophil survival coincided with increased numbers of neutrophils with a nonapoptotic phenotype, i.e. high levels of FcγRIII and L-selectin surface expression and intact morphology [15,31]. Second, addition of the enzyme at 40 µg/ml to an overnight culture of neutrophils just one hour prior to the normal staining procedure did not affect the number of apoptotic neutrophils determined afterwards.

Fig. 3.

Neutrophil apoptosis in an overnight culture. The percentage of Annexin-V/FITC-positive cells is shown. The role of PAF (–like) material was studied by (a) the addition of exogenous PAF (10−6 M), or in the presence of PAFR-antagonists WEB-2086 or TCV-309 [data not shown]; (b) enzymatically active rPAF-AH, in the indicated doses; (c) the apoptosis-inducing CD95 MoAb APO1–3 or the antiapoptosis CD95 MoAb Fas-2. Mean ± SD of 5–8 experiments performed on different occasions. Significance (P < 0·05) is marked by an asterisk (*). PAF-AH placebo is the vehicle (solvent).

The solvent solution for rPAF-AH (vehicle) did not have any effect on neutrophil functions, including apoptosis. Moreover, inactivation of the enzymatic activity (5 min, 100°C; or 10 min, 70°C) prevented the antiapoptotic effect of rPAF-AH completely (Fig. 3b). The possibility that the protective effect of rPAF-AH was due to formation of lyso-PAF, the natural product of PAF breakdown, was excluded by exogenous addition of lyso-PAF. There was no protective effect of lyso-PAF from 10−9 to 10−4 M; in contrast, an increase in neutrophil apoptosis at higher doses (Table 1). We subsequently tried to define the amount of PAF generated during the in-vitro cultures. At several time points (30 min, 1, 2, 6, and 15–16 h), PAF was undetectable in neutrophil cultures by a sensitive and PAF-specific competition assay.

Table 1.

Effect of lyso-PAF on neutrophil apoptosis in overnight cultures

| Addition | Apoptosis (%) (mean ± SD)* | Significance (P-value) |

|---|---|---|

| Control (15 h) | 78 ± 3 | |

| Lyso-PAF 10−6 M | 80 ± 5 | |

| Lyso-PAF 10−5 M | 83 ± 4 | < 0·05 |

| Lyso-PAF 10−4 M | 90 ± 3 | < 0·01 |

Values are expressed as percentage of neutrophils positive for Annexin-V/FITC staining after overnight cultures for 15 h. Mean ± SD of 8 experiments performed in duplicate on different occasions.

Next, we studied the effect of rPAF-AH on Fas-mediated apoptosis in neutrophils using the pro-apoptosis-inducing MoAb APO1–3. No inhibitory effect was seen, neither on early apoptosis (10 h) nor in overnight cultures (15–16 h). As a positive control the CD95 MoAb Fas-2 was added to show viability by blocking Fas-mediated death (Fig. 3c).

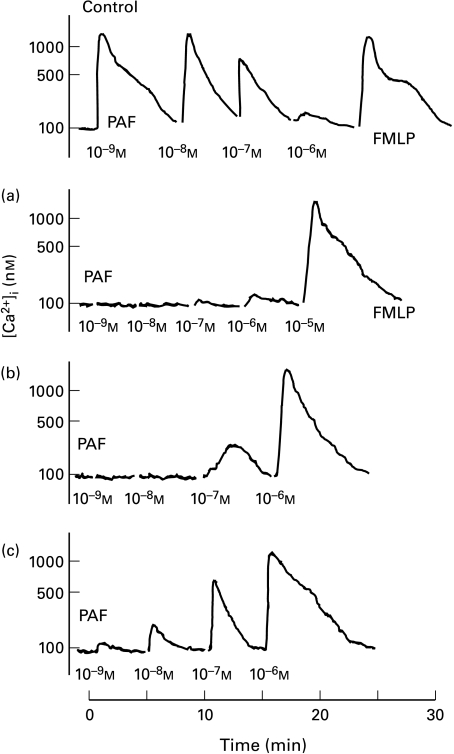

The efficiency to PAF-AH to prevent PAF-induced changes in cytosolic Ca2+

The lack of detectable PAF formation does not necessarily exclude a role of PAF in neutrophil apoptosis. Because of the stronger inhibitory potency of rPAF-AH over PAFR-antagonists in apoptosis, we determined the bioenzymatic efficacy with which rPAF-AH inactivates active PAF in a bioassay. One of the most sensitive and rapid responses of neutrophils to PAF (–like) substances consists of the changes in intracellular free calcium ions ([Ca2+]I). We compared the potency of PAFR-antagonists to inhibit PAF-induced [Ca2+]i responses with the ability of rPAF-AH to prevent these [Ca2+]i changes by breakdown of PAF. First of all, we tried to define the bioenzymatic activity of the rPAF-AH by simple co‐incubation of rPAF-AH to PAF, prior to the addition of (remaining) PAF to the indo-1/AM -loaded neutrophils. At 4 mg/ml (10−4 m), rPAF-AH completely prevented the normal PAF-induced changes induced by 1 mm PAF within 15 s of coincubation, which is in accordance with the Vmax of PAF-AH of about 167 µmol PAF/mg/h [17,32]. From these and additional tests, it follows that 1 molecule of rPAF-AH hydrolyses about 100–120 bioactive PAF molecules per minute. In general, catalysis by the neutral lipases and secretory phospholipases A2 (sPLA2) is enhanced at substrate concentrations above the critical micellar concentration (CMC). This means that plasma-derived PAF-AH with a CMCPAF of 1·1 µm is more active at PAF concentrations in the range of 0·01–1 mm [17,32]. Indeed, when the same amounts of rPAF-AH and PAF were coincubated in a 10,000-fold dilution (rPAF-AH 0·4 µg/ml; PAF 0·1 µm), i.e. below the CMC for PAF of 1·1 µm, a less effective catalysis was noticed. Only when coincubation was extended for 4 min or more, or when a 10-fold higher concentration of rPAF-AH was added, bioactive PAF was as efficiently degraded as described above [not shown].

To define the impact of rPAF-AH under more physiological conditions, rPAF-AH or PAFR-antagonists were added to the neutrophil suspension prior to the addition of PAF over a range of 10−11 up to 10−5 m PAF. In this way, the effect of PAFR-antagonists could be directly compared to that of rPAF-AH. First of all, the PAFR-antagonists WEB-2086 and TCV-309 (at 10 µm) were found to compete with PAF for PAFR binding up to a concentration of 3 × 10−7 m of PAF [not shown]. Yet, at concentrations of PAF that were no longer inhibited by the highest, nontoxic levels of these PAFR antagonists (50–100 µm), rPAF-AH was still able to counter neutrophil activation significantly.

At a very high concentration of rPAF-AH of 400 µg/ml, addition of PAF only at 10−5 m final concentration induced a clear rise in [Ca2+]i whereas 10−6 m of PAF did no longer induce this effect in the indo-1/AM-loaded neutrophils (Fig. 4a). When the neutrophils were preincubated with rPAF-AH at 40 µg/ml or 4 µg/ml, PAF induced a change of [Ca2+]i in neutrophils from 10−7 m and 10−9 m onward, respectively (Fig. 4 b,c). In the control trace, the normal pattern of PAFR desensitization upon stimulation with increasing doses of PAF is seen.

Fig. 4.

The effect of rPAF-AH on PAF-induced changes in [Ca2+]i in indo-1/AM-loaded neutrophils. Neutrophils (2 × 106/ml in incubation medium) were preincubated for 15 mins at 37°C in the absence (control) or presence of rPAF-AH at a concentration of 400 µg/ml (a), 40 µg/ml (b), or 4 µg/ml (c). Subsequently, PAF was added in a graded fashion from 10−9 m to 10−5 m. Desensitization of the PAFR at higher doses of PAF stimulation was excluded in this way, as well as in separate control traces [not shown]. FMLP (10−7 m) was included as positive control in all traces. rPAF-AH or vehicle did not induce by themselves any change of [Ca2+]i in neutrophils. Digitonin and Mn2+ was used for the calculation of cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration (see Material and methods).

DISCUSSION

Several mediators generated at the site of an inflammatory lesion have chemotactic activity, i.e. they bind to specific receptors on the surface of neutrophils and thus induce these cells to move to the inflammatory site, in a coordinated repertoire of adherence to vascular endothelium, diapedesis and migration [3]. Both under pathological and normal conditions of neutrophil turn-over, subsequent apoptosis of neutrophils and phagocytosis of the apoptotic cells by tissue macrophages is considered the normal sequence through which the neutrophils disappear. An important role for PAF in these processes of neutrophil extravasation and activation in the tissues has been strongly suggested in the past [7,8]. Although PAFR-antagonists have been shown to be effective in several in vitro and in vivo models, clinical applications in humans have not yet been established. An explanation may be found in the potency of PAF and in the lack of sustained levels of antagonists required for complete inhibition.

The use of enzymatically active rPAF-AH may be a potential alternative. Several PAF-induced neutrophil functions were found to be strongly inhibited by coincubation with rPAF-AH, as shown here for chemotaxis and changes in [Ca2+]i (Figs 1 and 4). The role of endogenously produced PAF or PAF-like substances in indirect granulocyte activation has previously been suggested for STZ-induced changes in [Ca2+]i [28,33]. Although not proven, the possibility of auto-activating PAF-like lipids may be extended to the late response of neutrophil apoptosis (Fig. 3a). Addition of PAF induced a significant increase in spontaneous apoptosis, whereas PAFR-antagonists increased survival. Most impressive was the ability of rPAF-AH to prevent neutrophils from undergoing apoptosis (Fig. 3b), whereas Fas-induced apoptosis was not prevented (Fig. 3c).

However, we were not able to detect PAF in neutrophil supernatant and cell extracts upon culture. This may be explained in two ways. First, levels of a continuous low-rate synthesis of PAF under the level of detection limit of the assay used may be responsible for the neutrophil apoptosis. Or alternatively, other PAF-like lipid mediators may be involved that cannot be detected by the radioimmunoassay used in this study, such as the PAF analogs with an acyl chain at the sn-1 position [34]. This last possibility is supported by the fact that the stringency to act on short acyl chains at the sn-2 position varies between the forms of PAF-AH [32]. Although PAF is the preferred substrate, plasma PAF-AH may act on substrates with an acyl-chain up to C5, or oxidatively damaged phospholipids up to an sn-2 C9 aldehyde homologue, some of which may activate the neutrophil in a way comparable to PAF [32,35]. Yet, all of these homologues exert their action through binding to the PAFR [33–36], leaving the mechanism involved in neutrophil apoptosis and the effect of plasma PAF-AH herein unchanged. On the other hand, the potent effect seen with rPAF-AH may relate to additional mechanisms not yet clarified, in which its enzymatic activity is required because heating and inhibition by the protease inhibitor Pefabloc abolish the effect of rPAF-AH on neutrophil apoptosis (Fig. 3b; and data not shown).

The potential use of rPAF-AH may be set back by the finding that PAF-AH was reported to deviate from normal Michaelis-Menten kinetics at low substrate concentrations. Hydrolysis of 1 nm of PAF by lipoprotein-associated PAF-AH activity proceeds at about 2% of the predicted rate [17]. This means that higher concentrations of rPAF-AH than predicted may be needed for a complete inactivation of PAF (–like) material. This inefficient enzymatic activity at low substrate concentrations can also explain the fact that rather high doses of rPAF-AH were required to significantly decrease the neutrophil responses as measured in this study. Another disadvantage of plasma PAF-AH may consist of its reported sensibility to oxidative inactivation [37]. In our determination of early [Ca2+]i changes (Fig. 4), PAF cannot induce NADPH oxidase activity in neutrophils under these conditions [11,12]. The role of oxidation by neutrophil-derived toxic oxygen metabolites during an overnight culture was excluded in two ways. First, addition of catalase did not result in enhanced neutrophil survival at lower doses of rPAF-AH in the overnight cultures. Second, dose–response curves for rPAF-AH were unchanged when neutrophils were used from two patients with Chronic Granulomatous Disease (unable to generate toxic oxygen radicals because of an inherent defect in the NADPH-oxidase complex [38]). Spontaneous apoptosis of these neutrophils was also not different from normal control neutrophils [not shown].

On the other hand, an enormous advantage in vivo of rPAF-AH as compared to the use of PAFR-antagonists lays in its capacity to afford strong and long-term protective effects against PAF and PAF-like substances through its half-life of 30–38 h in humans [39], as was recently substantiated by our observations in a rat model of anaphylactic shock mediated by endogenous PAF. Once the animals are in shock, the beneficial effects of PAFR-antagonists rapidly declined after their intravenous bolus administration in these animals, whereas rPAF-AH provided a rapid improvement followed by a prolonged protection from the shock effects on various cardiovascular parameters [40]. Because plasma concentrations of PAF during severe infections occur in the picomolar range, even a 10-fold increase in plasma concentration of rPAF-AH may suffice to inhibit neutrophil activation by PAF within the circulation or the tissues. The beneficial and prolonged effects of rPAF-AH is further indicated by our findings on early changes in [Ca2+]i, and chemotaxis, as well as in late long-term survival.

Clearly, the anti-inflammatory effects of PAFR-antagonists or PAF-AH on early granulocyte activation and extravasation during PAF-mediated or -promoted inflammation may now be extended to a more late-phase protection from too rapid neutrophil decay. An increased number of neutrophils present at a site of inflammation does not necessarily result in an increase of tissue damage [41]. Prolonged survival and activity of the inflammatory neutrophils in the tissues can have positive effects, e.g. on the killing of pathogens and (hence) on mortality. This was suggested in studies on bacterial pneumonia and ARDS showing a correlation between a decreased rate of neutrophil apoptosis and effective control of pulmonary inflammation [42,43]. On the other hand, neutrophil apoptosis may also represent a mechanism of the host to protect itself from harmful effects of a potentially toxic cell and overt spillage of its proteolytic enzymes [44]. Yet, we believe that a delay in neutrophil apoptosis is more relevant as a harmful and pathologic event under conditions of autoimmunity or chronic inflammatory responses when protease inhibition is impaired [45]. Until now, the beneficial effect of rPAF-AH has been shown in acute inflammatory models [18,40,46]. Prolonged survival and activity of neutrophils may be another aspect of the beneficial effects of rPAF-AH in vivo.

Acknowledgments

TW Kuijpers is a research fellow of the Royal Dutch Acadamy of Sciences. We thank Drs CE Hack and AJ Verhoeven for critically reading the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Snyder F. Biochemistry of Platelet-activating Factor: a unique class of biologically active phospholipids. FASEB J. 1989;190:125–35. doi: 10.3181/00379727-190-42839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chao W, Olson MS. Platelet-activating factor: receptors and signal transduction. Biochem J. 1993;292:617–29. doi: 10.1042/bj2920617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuijpers TW, van de Poll T. The role of PAF in endotoxin-related disease. In: Morrison D, et al., editors. Endotoxin and Disease. New York: Bauer Press; 1999. pp. 449–62. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Honda Z, Nakamura M, Miki I, et al. Cloning by functional expression of platelet-activating factor receptor from guinea-pig lung. Nature. 1991;349:342–4. doi: 10.1038/349342a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakamura M, Honda Z, Izumi T, et al. Molecular cloning and expression of platelet-activating factor receptor from human leukocytes. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:20400–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ye RD, Prossnitz ER, Zou A, Cochrane CG. Characterization of a human cDNA that encodes a functional receptor for platelet activating factor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;15:105–11. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)81261-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mutoh H, Ishii S, Izumi T, Kato S, Shimizu T. Platelet-activating factor (PAF) positively auto-regulates the expression of human PAF receptor transcript 1 (leukocyte-type) through NF-kappa B. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;15:1137–42. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mutoh H, Kume K, Sato S, Kato S, Shimizu T. Positive and negative regulations of human platelet-activating factor receptor transcript 2 (tissue-type) by estrogen and TGF-beta 1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;15:1130–6. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuijpers TW, Hakkert BC, Hart MHL, Roos D. Neutrophil migration across monolayers of cytokine-prestimulated endothelial cells: a role for Platelet-activating Factor and IL-8. J Cell Biol. 1992;117:565–72. doi: 10.1083/jcb.117.3.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nourshargh S, Larkin SW, Das A, Williams TJ. Interleukin-1-induced leukocyte extravasation across rat mesenteric microvessels is mediated by platelet-activating factor. Blood. 1995;85:2553–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bokoch GM. Chemoattractant signalling and leukocyte activation. Blood. 1995;86:1649–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nick JA, Avdi NJ, Young SK, Knall C, Gerwins P, Johnson GL, Worthen GS. Common and distinct intracellular signaling pathways in humen neutrophils utilized by platelet-activating factor and FMLP. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:975–86. doi: 10.1172/JCI119263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colotta F, Re F, Polentarutti N, Sozzani S, Montovani A. Modulation of granulocyte survival and programmed cell death by cytokines and bacterial products. Blood. 1992;80:2012–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whyte MKB, Meagher LC, MacDermot J, Haslett C. Impairment of function in ageing neutrophils is associated with apoptosis. J Immunol. 1993;150:5123–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Homburg CHE, de Haas M, dem Borne AEG, Kr Verhoeven AJ, Reutelingsperger CPM, Roos D. Human neutrophils lose their surface FcãRIII and acquire Annexin V binding sites during apoptosis in vitro. Blood. 1995;85:532–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murray J, Barbara JAJ, Dunkley SA, et al. Regulation of neutrophil apoptosis by tumor-necrosis factor-á: requirements of TNFR55 and TNFR75 for induction of apoptosis in vitro. Blood. 1997;90:2772–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stafforini DM, Prescott SM, Zimmerman GA, McIntyre TM. Mammalian platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolases. BBA. 1996;1301:161–73. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(96)00040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tjoelker LW, Wilder C, Eberhardt C, et al. Anti-inflammatory properties of a platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase. Nature. 1995;374:549–53. doi: 10.1038/374549a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hattori K, Adachi H, Matsuzawa A, et al. cDNA cloning and expression of intracellular platelet activating factor (PAF) acetylhydrolase II. its homology with plasma acetylhydrolase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:33032–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.33032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swenson HYS, Derewenda U, Serre L, et al. Brain acetylhydrolase that inactivates platelet-activating factor is a G-protein-like trimer. Nature. 1997;385:89–93. doi: 10.1038/385089a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldstein IM, Roos D, Kaplan HB, Weissmann G. Complement and immunoglobulins stimulate superoxide production by human leukocytes independently of phagocytosis. J Clin Invest. 1975;56:1155–61. doi: 10.1172/JCI108191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roos D, de Boer M. Purification and cryopreservation of phagocytes from human blood. Meth Enzymol. 1986;132:225–55. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(86)32010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuijpers TW, Mul FPJ, Blom M, Kovach NL, Gaeta FCA, Tollefson V, Elices MJ, Harlan JM. Freezing adhesion molecules in a state of high-avidity binding blocks eosinophil migration. J Exp Med. 1993;78:279–84. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.1.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamers MN, Bot AAM, Weening RS, Sips HJ, Roos D. Kinetics and mechanism of the bactericidal action of human neutrophils against Escherichia coli. Blood. 1984;64:635–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pozzan T, Lew DP, Wollheim CB, Tsien RY. Is cytosolic ionized calcium regulating neutrophil activation? Science. 1983;22:1413–5. doi: 10.1126/science.6310757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bijsterbosch MK, Rigley KP, Klaus GGB. Crosslinking of surface immunoglobulin on B lymphocytes induces both intracellular Ca2+ release and Ca2+ influx: analysis with indo-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1985;37:500–6. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(86)91238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grynkiewicz GM, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985;258:3440–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tool ATJ, Koenderman L, Kok PTM, Blom M, Roos D, Verhoeven AJ. Release of platelet-activating factor is important for the respiratory burst induced in human eosinophils by opsonized particles. Blood. 1992;79:2729–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verhoeven AJ, Tool ATJ, Kuijpers TW, Roos D. Nimesulide inhibits platelet-activating factor synthesis in activated human neutrophils. Drugs. 1993;46:52–8. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199300461-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stewart AG, Cotterill T, Harris T. Granulocyte and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factors exert differential effects on neutrophil platelet-activating factor generation and release. Immunology. 1994;82:51–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsuba KT, van Eeden SF, Bicknell SG, Walker BAM, Hayashi S, Hogg JH. Apoptosis in circulating PMN. increased susceptibility in l-selectin-deficient PMN. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:H2852–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.6.H2852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stremler KE, Stafforini DM, Prescott SM, McIntyre TM. Human plasma platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase. Oxidatively fragmented phospholipids as substrates. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:11095–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tool ATJ, Verhoeven AJ, Roos D, Koenderman L. Platelet-activating factor (PAF) acts as an intercellular messenger in the changes of cytosolic free Ca2+ in human neutrophils induced by opsonized particles. FEBS Lett. 1989;259:209–14. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81530-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pinckard RN, Showell HJ, Castillo R, Lear C, Breslow R, McManus LM, Woodard DS, Ludwig JC. Differential responsiveness of human neutrophils to the autocrine actions of 1-O-alkyl-homologs and 1-acyl analogs of platelet-activating factor. J Immunol. 1992;48:3528–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patel KD, Zimmerman GA, Prescott SM, McIntyre TM. Novel leukocyte agonists are released by endothelial cells exposed to peroxide. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:15168–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smiley PL, Stremler KE, Prescott SM, Zimmerman GA, McIntyre TM. Oxidatively fragmented phosphatidylcholines activate human neutrophils through the receptor for platelet-activating factor. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:11104–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ambrosio G, Oriente A, Napoli C, et al. Oxygen radicals inhibit human plasma acetylhydrolase, the enzyme that catabolizes platelet-activating factor. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:2408–16. doi: 10.1172/JCI117248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roos D, de Boer M, Kuribayashi F, et al. Mutations in the X-linked and autosomal recessive forms of chronic granulomatous disease. Blood. 1996;87:1663–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pribble J, Yu A, Peterman G. Evaluations of the safety, pharmacokinetics and clinical pharmacology of recombinant human platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase in healthy subjects and critically ill patients. 6th International Congress on Platelet-activating Factor and Related Lipid Mediators, New Orleans. :A33. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bleeker W, Teeling JL, Verhoeven AJ, et al. Vasoactive side effects of intravenous immunoglobulin presss in a rat model and their treatment with recombinant platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase. Blood. 2000;95:1856–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eichacker PQ, Waisman Y, Natanson C, Farese A, Hoffman WD, Banks SM, MacVittie TJ. The cardiopulmonary effects of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in a canine-model of bacterial sepsis. J Appl Physiol. 1994;77:2366–73. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.77.5.2366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Droemann D, Aries SP, Hansen F, Moellers M, Braun J, Katus HA, Dalhoff K. Decreased apoptosis and increased activation of alveolar neutrophils in bacterial pneumonia. Chest. 2000;117:1679–84. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.6.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matute-Bello G, Liles WC, Radella F, Steinberg KP, Ruzinski JT, Hudson LD, Martin TR. Modulation of neutrophil apoptosis by granulocyte colony stimulating factor and granulocyte/macrophage colony stimulating factor during the course of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:1–7. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200001000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Giles KM, Hart SP, Haslett C, Rossi AG, Dransfield I. An appetite for apoptosis cells? Controversies Challenges Br J Haematol. 2000;109:1–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.01805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weiss SJ. Mechanisms of disease: tissue desctruction by neutrophils. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:365–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198902093200606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim JD, Baker CJ, Roberts RF, Darbinian SH, Marcus KA, Quardt SM, Starnes VA, Barr ML. Platelet activating factor acetylhydrolase decreases lung perfusion injury. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70:423–8. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)01405-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]