Abstract

A T helper (Th)1 to Th2 shift has been proposed to be a critical pathogenic determinant in chronic hepatitis C. Here, we evaluated mitogen-induced and hepatitis C virus (HCV) core antigen-induced cytokine production in 28 patients with biopsy-proven chronic hepatitis C. Flow cytometry demonstrated that after mitogenic stimulation the percentage of Th2 cells (IL-4 + or IL-13 +) and Th0 cells (IFN-γ/IL-4 + or IL-2/IL-13 +) did not differ between patients and controls. In contrast, the percentage of Th1 cells (IFN-γ + or IL-2 +) was significantly increased in CD4 +, CD8 +, ‘naive’-CD45RA + and ‘memory’-CD45RO + T-cell subsets from patients versus controls. Similar results were obtained by ELISA testing supernatants from mitogen-stimulated, unfractionated peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) cultures. Interferon-alpha treatment was associated with a reduction in the mitogen-induced Th1 cytokine response in those patients who cleared their plasma HCV-RNA. Analysis of cytokine expression by CD4 + T cells after HCV core antigen stimulation in a subgroup of 13 chronic hepatitis C patients demonstrated no cytokine response in 74% of these patients and an IFN-γ-restricted response in 26%. Finally, no Th2 shift was found in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated monocytes. These data indicate that a Th1 to Th2 shift does not occur in chronic hepatitis C.

Keywords: HCV, cytokine, lymphocytes, monocytes, interferon-alpha

INTRODUCTION

Nearly 50% of the individuals affected by acute hepatitis C develop a chronic infection which gives rise, in 15–20% of the infected individuals, to cirrhosis or cancer of the liver [1]. Several determinants such as the vigour of the T-cell proliferative response to hepatitis C virus (HCV) antigens in the acute phase of hepatitis [2–4], the strength of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) activity against HCV epitopes [5,6], the genetic factors of the infected hosts [7–9] and the genotype of the virus in association with its quasi-species nature [10,11] have all been suggested as important factors capable of influencing the outcome of acute HCV infection. In addition, it has been recently proposed that the inability to terminate HCV infection may also result from the inappropriate release of some T-cell and monocyte-macrophage derived cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-10 [12,13]. These cytokines (also called T helper (Th)2-type cytokines) have been found in high levels in blood from patients with chronic hepatitis C [20,21], and may inhibit cellular mediated antiviral responses by interfering with T cell activation and function [16–19].

To address the question of Th2 cytokine disregulation in chronic HCV infection, we undertook several experimental approaches. First, we determined the pattern of cytokine production in T cells after stimulation with mitogens or HCV core antigen and in monocytes stimulated by lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Second, we quantified by ELISA cytokine production by unfractionated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) after mitogenic stimulation. This analysis gives an estimate of the total cytokine synthetic ability of PBMC. Third, to observe changes in the pattern of cytokine expression in relation to viral clearance, we performed longitudinal analysis of mitogen-induced cytokine expression in T lymphocytes collected from the same patients before and after a 4-month course of IFN-alpha (IFN-α) therapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and interferon treatment

Twenty-eight patients with chronic hepatitis C (16 male and 12 female, mean age 56 years, range 28–67 years) were included in this study (Table 1). Inclusion criteria were: the presence of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels at more than twice the upper limit of the normal range for at least six months; anti-HCV antibodies detected by third generation test (ELISA, recombinant-based immunoblot assay, Abbott, Pomezia, Italy); detectable serum HCV-RNA; and liver biopsy findings compatible with chronic hepatitis C. Patients with chronic hepatitis B and autoimmune hepatitis were excluded. Two patients had a history of past drug abuse, none had a history of blood transfusion or alcoholism. Fourteen of the patients were treated with human recombinant IFN-α at a dose of six million units three times a week, for a minimum period of four months. Liver biopsies were performed before IFN-α treatment and were graded and staged according to Ishak et al. [22]. None of the patients had fever, evidence of other infectious diseases, inflammatory disorders or any kind of malignancy at the time the serum samples were obtained. No persons who were taking immunosuppressive medications within the previous 6 months were included. A total of 26 age and sex matched healthy volunteers were taken as controls. Informed consent was obtained from each individual.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients at entry into the study

| Variable | Baseline data |

|---|---|

| N° of patients | 28 |

| Mean age (years) | 56 |

| Sex (M/F) | 16/12 |

| Years from the first diagnosis of | 6·9 |

| HCV-relatedliver disease | |

| Histological grading (n° of patients)* | |

| 1–7 | 16 |

| 8–15 | 10 |

| Histological staging (n° of patients) | |

| 1 | 3 |

| 2 | 5 |

| 3 | 11 |

| 4 | 3 |

| 5 | 6 |

| ALT (mU/ml) | 88 ± 54 |

| HCV RNA levels (copies/ml × 103) | 838 ± 233 |

| Genotype (n° of patients) | |

| 1b | 16 |

| not 1b | 7 |

| unknown | 5 |

Note. Data are expressed as mean ± SD ALT, alanine aminotransferase (normal range < 21 mU/ml).

Cells

Blood was collected into sterile EDTA tubes and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were immediately separated using lymphoprep (Nycomed, Oslo, Norway). PBMC were resuspended at a final concentration of 10 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 containing 2 mm glutamine, 50 U/ml penicillin, 50 µg/ml streptomycin, and 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (complete medium). All cultures were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2.

FACS analysis

For mitogen-and LPS-induced cytokine responses, 2 × 106 PBMC were cultured for 18 h in complete medium supplemented with either 20 ng/ml phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) plus 500 ng/ml ionomycin (IO) (both from Calbiochem-Novabiochem INTL, La Jolla CA) or 100 ng/ml (LPS) from Escherichia coli 0111/B4 (Sigma Chemical Co. St. Louis, MO). 1 µg/ml brefeldin A (Sigma Chemical Co. St. Louis, MO) was added 1 h after stimulation to inhibit cytokine export. For HCV core antigen-induced cytokine responses, 2 × 106 PBMC were incubated in culture tubes at a 5° slant in complete medium supplemented with 1 µg/ml HCV core antigen (aa 2 to aa 196, Biogenesis Inc., Kingston, NH, USA) for a total of 6 h, with brefeldin A at a final concentration of 1 µg/ml present for the last 5 h.

At the end of the incubation periods, the cells were collected and washed twice in PBS by centrifugation. Dead cells were excluded by trypan blue dye and 2 × 105 viable PBMC in 20 µl PBS were dispensed in V-bottom 96 plates. Cells were then incubated for 15 min with one of the following mouse antihuman monoclonal antibodies: Cy-chromeTM-conjugated (Cy-chrome)-anti-CD3 and anti-CD14 or phycoerytrin-conjugated (PE)-anti-CD8, anti-CD45RA, anti-CD45RO (all from PharMingen, San Diego CA). In the mitogen-stimulated samples, staining with anti-CD8 antibody enabled the T cells to be subdivided into CD8 + and CD8-cells, those cells which did not stain for CD8 were assumed to represent the CD4 + T cell population. These cells could not be stained directly since treatment of lymphocytes with PMA plus IO leads to rapid and complete down modulation of surface CD4 [23]. In LPS-and HCV core antigen-stimulated samples, no down modulation of surface CD4 was observed, therefore allowing direct staining of CD4 + cells with PE-anti CD4 antibody.

The cells were then washed twice in PBS and fixed in ice cold PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde. After two further washes in PBS, cells were resuspended for 30 min at room temperature in 20 µl PBS containing 0·1% saponin (Sigma Chemical Co. St. Louis, MO), 1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma) and 0·5 µg/million cells of the following monoclonal antibodies: fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated (FITC)-anti-IL-4, -IL-6, -IL-10, -IL-13, IFN-γ and -IL-2 (PharMingen, San Diego CA) or PE-anti-IL-4, -IL-10 and -IL-13 (PharMingen). As a last step, the cells were washed twice in PBS containing 0·01% saponin, resuspended in PBS and analysed by a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, USA). Lymphocytes and macrophages were differentiated from dead cells on the basis of forward angle and 90° scatter. For each analysis, either 5000 events (mitogen-stimulated cultures) or 50 000 events (HCV core antigen-stimulated cultures) were gated on CD3, CD8 or CD4 expression and a light scatter gate designed to include only viable lymphocytes, and analysed using the FACScan research software (Becton Dickinson). Isotype-matched negative controls antibodies (PharMingen) were used to verify the staining specificity of anti cytokine antibodies, and as a guide for setting markers to delineate ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ populations.

Measurement of unfractionated PBMC cytokine production by ELISA

For the determination of cytokine production in supernatants, 4 × 106 PBMC were cutured for 48 h in complete medium supplemented with PMA plus IO as described above, in the absence of brefeldin A. After incubation, supernatants were collected and stored at − 80°C. Commercially available sandwich ELISA kits (R & D Systems Minneapolis, MN) were used to determine the concentration of IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, IFN-γ and IL-2 in the supernatants. The detection limits of these ELISAs are, respectively, 4·1, 1·5, 15, 7 and 3 pg/ml. According to the manufacturer's specifications, these ELISAs are specific for the relative cytokines. All samples were tested in duplicate, in a single analytical set. Intra-series variation coefficient was < 15%.

HCV-RNA

The quantification of HCV-RNA in serum samples was performed using a commercially available kit: Amplicor HCV monitorTM test (Roche Diagnostic Systems, Branchburg, NJ). The lowest level of detection of this test is less than 200 HCV-RNA copies/ml of sample.

Statistics

Data analysis was performed using unpaired Student's t-test. P-values < 0·05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

FACS analysis of cytokine expression by mitogen-and HCV core antigen-stimulated T lymphocytes and LPS-stimulated monocytes

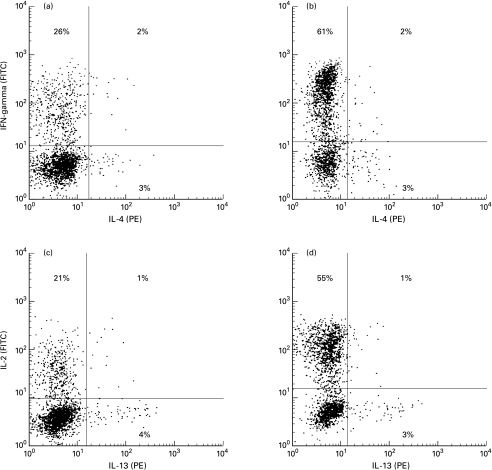

PBMC were stimulated with PMA plus IO, stained for intracellular IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, IFN-γ and IL-2, and analysed by three-colour FACS analysis with a gate on Cy-chrome-anti CD3 + T cells. The expression of IL-10 was either barely detectable or undetectable in the majority of the samples from both controls and patients. As shown in Table 2 and Fig. 1 the percentage of cells that expressed IL-4 and IL-13 but stained negative for IFN-γ and IL-2 (Th2 cells), as well as the percentage of cells capable of simultaneously synthesizing both IFN-γ and IL-4 or IL-2 and IL-13 (Th0 cells), did not differ between patients and controls. In contrast, the percentage of T lymphocytes that produced exclusively IFN-γ and IL-2 (Th1 cells) was significantly higher in patients than in controls.

Table 2.

Cytokine expression of mitogen-stimulated CD3 + T lymphocytes from HCV patients and controls

| Percentage of positive cells | ||

|---|---|---|

| Cytokine | Controls | Patients |

| IL-4 | 3·7 ± 2·7 | 4·7 ± 2·8 |

| IL-13 | 2·4 ± 0·5 | 2·7 ± 1·2 |

| IFN-γ/IL4 | 1·4 ± 0·5 | 1·8 ± 1 |

| IFN-γ/IL-13 | 1·7 ± 1 | 2 ± 1·5 |

| IFN-g | 24 ± 11 | 41 ± 20 (P = 0·001) |

| IL-2 | 31 ± 20 | 52 ± 19 (P = 0·001) |

Note. Mitogen-stimulated PBMC were stained with Cy-chrome-anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody for the determination of their surface phenotype. Intracellular cytokines were detected by staining with FITC-anti-IFN-γ and -anti-IL-2 or PE-anti-IL-4 and -anti-IL-13 monoclonal antibodies. CD3 + gated lymphocytes were analysed by FACS on FL1 (FITC) versus FL2 (PE) two-dimensional plots to discriminate positive cells. If not indicated P ≥0·05. Data are means ± SD

Fig. 1.

Detection of T-helper (Th)-1, Th2 and Th0 cells by cytofluorimetric analysis. Mitogen-stimulated PBMC were stained as described in the legend to Table 2 and analysed on FL1 (FITC) versus FL2 (PE) two-dimensional plots to discriminate positive cells. (a, c) PBMC from a typical control subject. (b, d) PBMC from a typical patient. Left lower quadrants: unstained cells. Left upper quadrants: Th1 cells staining positive exclusively for FITC-anti-IFN-γ or anti-IL-2 monoclonal antibodies. Lower right quadrants: Th2 cells staining positive exclusively for PE-anti-IL-4 and anti-IL-13 monoclonal antibodies. Right upper quadrants: Th0 cells staining simultaneously for anti-IFN-γ plus anti-IL4 or anti-IL-2 plus anti-IL-13 monoclonal antibodies.

To better characterize the modulation of cytokine expression that takes place in HCV-infected patients, we determined the cytokine patterns of various T lymphocyte subsets after mitogenic stimulation. The analysis shown in Table 3 demonstrates no significant difference in the percentage of Th2 cells between patients and controls. In contrast, the percentage of positive cells for IFN-γ and IL-2 was significantly increased in CD8-, CD8 +, ‘naive’ CD3 + CD45RA + and ‘memory’ CD3 + CD45RO + cells in patients as compared with controls.

Table 3.

Cytokine expression of mitogen stimulated T lymphocyte subsets from controls and patients

| Percentage of positive cells | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T cell subsets | Cytokine | Controls | Patients | P-value |

| CD8- | IL-4 | 3·7 ± 1·6 | 4·5 ± 2·4 | |

| IL-13 | 2·3 ± 0·9 | 2·6 ± 1.0 | ||

| IFN-γ | 25·6 ± 14 | 43·6 ± 15 | P = 0·001 | |

| IL-2 | 36·6 ± 21 | 63·3 ± 24 | P = 0·001 | |

| CD8 + | IL-4 | 3·8 ± 1·6 | 4·9 ± 2·5 | |

| IL-13 | 2·1 ± 1·1 | 2·8 ± 1·4 | ||

| IFN-γ | 17·2 ± 9·6 | 35·5 ± 19 | P = 0·001 | |

| IL-2 | 15·4 ± 10 | 31·2 ± 15 | P = 0·001 | |

| CD3 + CD45RA + | IL-4 | 3·5 ± 1·5 | 5.0 ± 2·1 | |

| IL-13 | 2·1 ± 1·3 | 2·2 ± 1·1 | ||

| IFN-γ | 20.0 ± 11 | 3.08 ± 17 | P = 0·001 | |

| IL-2 | 34.0 ± 15 | 54.0 ± 14 | P = 0·001 | |

| CD3 + CD45RO + | IL-4 | 4.0 ± 2·3 | 4·4 ± 1.0 | |

| IL-13 | 2·5 ± 1·6 | 3.0 ± 1·9 | ||

| IFN-γ | 26.0 ± 14 | 43.0 ± 15 | P = 0·001 | |

| IL-2 | 28.0 ± 13 | 50.0 ± 11 | P = 0·001 | |

Mitogen-stimulated PBMC were stained with Cy-chrome-anti-CD3 plus one of the following PE-monoclonal antibodies: anti-CD8, anti-CD45RA or anti-CD45RO for the determination of surphace phenotype. Intracellular cytokines were detected by staining with FITC-anti-IFN-γ, -anti-IL-2, -anti-IL-4 and -anti-IL-13 monoclonal antibodies. CD3 + gated lymphocytes were analysed by FACS on FL1 (FITC) versus FL2 (PE) two-dimensional plots to discriminate positive cells. If not indicated P ≥0·05. Data are means ± SD

A novel, highly efficient multiparameter flow cytometric assay that allows precise quantification of the percentage of cells producing cytokines in response to antigen stimulation [24,25] was employed to further analyse a subgroup of 13 HCV-patients. Table 4 shows that HCV core antigen stimulation did not induce a cytokine response in 69% of patients but induced an IFN-γ-restricted response in 31% of patients. This response ranged from 0·011% to 0·024% of IFN-γ−positive CD4 + T cells. The percentage of CD4 + T cells that responded to HCV core antigen stimulation with IL-2, IL-4 IL-10 and IL-13 production was constantly below 0·02%, the same found in samples from HCV core antigen-stimulated-HCV-negative subjects (n = 8) (data not shown). In the 4 patients in which an IFN-γ response was observed there was a trend toward an increased mitogen-induced IFN-γ and IL-2 response of CD8-cells, with respect to the HCV core antigen-unresponsive patients (54·2% versus 37·6% and 76·5% versus 53% mean responding cells for IFN-γ and IL-2, respectively).

Table 4.

Cytokine production by CD4 + T lymphocytes from HCV-infected patients, stimulated with HCV core antigen, as compared to mitogen stimulation

| Percentage of positive cells | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| PMA/IO-stimulation | |||

| HCV-core-stimulation | |||

| Patient | IFN-γ | IL-2 | IFN-γ |

| 1 | 55 | 88 | 0·17 |

| 2 | 50 | 55 | < 0·02 |

| 3 | 35 | 47 | < 0·02 |

| 4 | 32 | 44 | < 0·02 |

| 5 | 40 | 62 | < 0·02 |

| 6 | 62 | 71 | 0·24 |

| 7 | 40 | 65 | < 0·02 |

| 8 | 50 | 65 | 0·11 |

| 9 | 37 | 55 | < 0·02 |

| 10 | 43 | 51 | < 0·02 |

| 11 | 33 | 47 | < 0·02 |

| 12 | 50 | 82 | 0·14 |

| 13 | 29 | 56 | < 0·02 |

For each patient, mitogen-and HCV core antigen-stimulated cultures were run simultaneously. Mitogen-stimulated cultures were stained as described in the legend to Table 2, those cells which did not stain for CD8 were assumed to represent the CD4 + T cell population. HCV core antigen-stimulated PBMC were stained with Cy-chrome-anti-CD3 plus PE-anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody and FITC-anti-IFN-γ monoclonal antibodies. CD3 + gated cells were analysed by FACS on FL1 (FITC) versus FL2 (PE) two-dimensional plots to discriminate positive cells. The number of positive events calculated in the same samples in the absence of antigen stimulation was constantly below 0·02.

No significant difference was found between controls and patients with respect to the percentage of CD4 + (61 ± 9% versus 64 ± 10%, P > 0·5), CD8 + (38 ± 10% versus 35 ± 11%, P > 0·5), CD3 + CD45RO + (43 ± 17% versus 54 ± 16%, P > 0·5) and CD3 + CD45RA + (51 ± 10% versus 56 ± 12%, P > 0·5) cells. No significant correlation was found between mitogen-and HCV core antigen-induced cytokine expression, and plasma HCV-RNA values (HCV RNA < 10 × 105 copies/ml versus HCV RNA > 10 × 105 copies/ml), histological grading (1–7 versus 8–15) and staging (1–3 versus 4–5), viral genotype (1b versus not 1b) and basal levels of serum ALT (normal ALT versus increased ALT) (data not shown).

Cells of the monocyte/macrophage lineage are an important source of pro-inflammatory and immunoregulatory cytokines in vivo, which may contribute either directly or indirectly to the development of polarized Th1 or Th2 response in T lymphocytes [13]. For these reasons intracellular staining and FACS analysis was also employed to examine cytokine expression in peripheral blood monocytes after in vitro stimulation by LPS. Variable proportions of cells stained positive for IL-4, IL-6 and IL-10; however, the expression of these cytokines did not differ between controls and patients (33 ± 16 versus 29 ± 15, P≥0·05; 8·2 ± 1·7 versus 8·7 ± 2·2, P≥0·05; 4 ± 4·6 versus 4·8 ± 6, P≥0·05 for IL-4, IL-6 and IL-10, respectively).

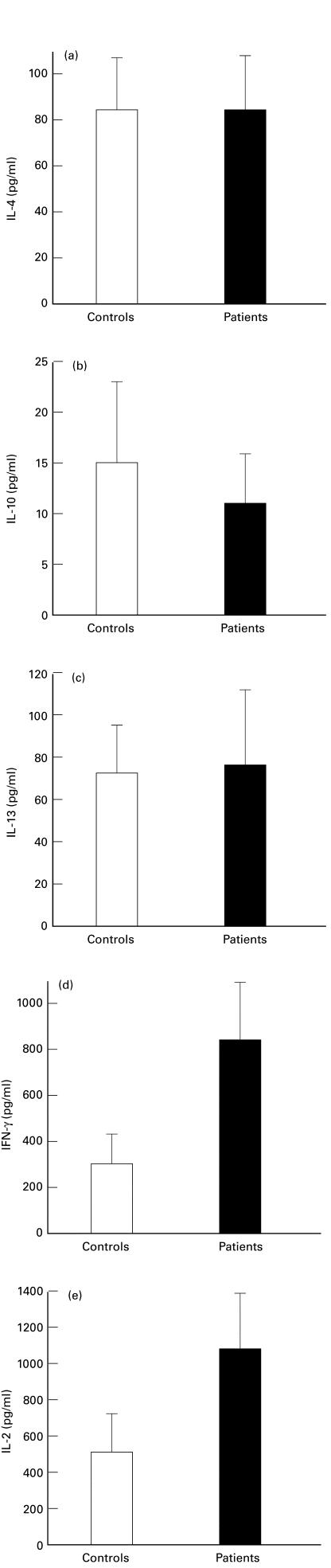

Cytokine expression in unfractionated PBMC

To confirm and expand the data obtained by FACS, cytokine expression was further evaluated in unfractionated PBMC after activation in vitro with PMA and IO (Fig. 2). Overall expression of IL-4, IL-10 and IL-13 did not differ between controls and patients (P≥0·05). Expression of IFN-γ and IL-2 was greater in patients compared to that in controls (P = 0·01 and 0·02 for IFN-γ and IL-2, respectively).

Fig. 2.

Cytokine measurement of mitogen-induced cytokine production by ELISA testing of supernatants from unfractionated peripheral blood mononuclear cells. a, IL-4; b, IL-10; c, IL-13; d, IFN-γ; e, IL-2.Bars represent S.D.

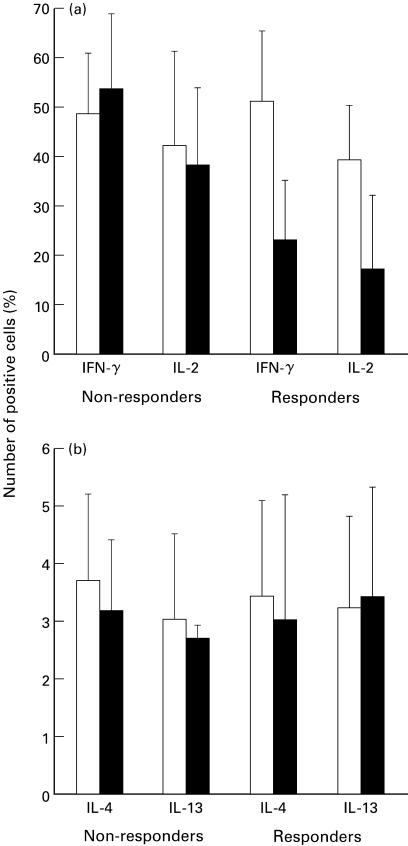

Effect of IFN-α treatment on cytokine production

Cytokine production by mitogen-stimulated T cells was prospectively studied by FACS analysis in 14 HCV patients undergoing IFN-α treatment. Four months after IFN-α therapy had started, patients were divided empirically into two groups according to their values of plasma HCV-RNA values: (i) nonresponders (n = 9) with detectable plasma HCV-RNA; (ii) responders (n = 5) with undetectable plasma HCV-RNA. All but two nonresponders had persistently abnormal serum ALT levels, whereas all the responders gained normal ALT levels. As shown in Fig. 3, cytokine measurement showed a trend toward decreased expression of both IFN-γ and IL-2 in responders as compared with nonresponders. In contrast, IL-4 and IL-13 production did not change significantly during IFN-α treatment in either group. No correlation was found between the percentage of IFN-γ and IL-2 expressing cells measured before the start of IFN-α treatment and the ability of patients to clear their HCV-RNA.

Fig. 3.

Cytokine expression by in vitro activated T lymphocytes from HCV patients before (□) and after four months (▪) of IFN-α therapy. Mitogen-stimulated PBMC were stained as described in the legend to Table 2 and analysed by FACS. Bars represent S.D.

DISCUSSION

In the present report the cytokine phenotype of peripheral blood T lymphocytes and monocytes from patients with chronic hepatitis C has been examined. Evaluation of mitogen-induced cytokine production demonstrated no evidence of an increase in either Th2/Th0 T lymphocyte populations or production of Th2-type cytokines. In contrast, the Th1 T lymphocyte population, as well as the production of Th1-type cytokines, increased after mitogen stimulation in lymphocytes from patients with respect to controls. In addition, analysis of cytokine expression by CD4 + T cells after HCV core antigen stimulation in a subgroup of patients showed either no cytokine response in 69% of patients or an IFN-γ-restricted response in 31%.

Our findings are in contrast with data from authors who found an increase in Th2-type cytokines in serum from HCV infected individuals [20,21]; however, the attempts made so far to determine the cytokine profile associated with chronic HCV infection by ELISA testing of sera for cytokine concentrations have produced contrasting results ranging from the demonstration of a mutually exclusive Th1 [26] or Th2 [20] predominance to the evidence of rather broad up-regulation of cytokine production involving both Th1-and Th2-type cytokines [21]. These discrepancies are probably the result of methodological drawbacks associated with ELISA measurement of serum samples. Indeed, the levels of serum cytokines are easily affected by diurnal fluctuations in immune activity. Moreover, quantification of serum cytokine levels using ELISAs may be misleading as specific binding proteins exist for a number of cytokines, including autoantibodies, α2-macroglobulin, heterophilic antibodies and soluble cytokine receptors, all of which interfere with cytokine detection [27,28]. Finally, cytokine levels measured by ELISA are the net of protein synthesis, consumption and biodegradation. In contrast, we studied the production of cytokines by T lymphocytes and monocytes by a FACS strategy that allowed the identification of producer cells by cell surface markers and cytokine production simultaneously, and coupled this with a bulk-release method, i.e. ELISA testing of supernatants from unfractionated cell cultures [29–32]. It is likely that these techniques are more suitable than the measurement of circulating cytokines to study primarily cell-based phenomena, such as the modulation of cytokine patterns associated with chronic viral infections.

In addition, we have evaluated the HCV core antigen-specific CD4 + T cell cytokine response in a subgroup of 13 patients. To this end, we employed a recently developed, FACS-based assay that visualizes individual antigen-responsive CD4 + T cells with unprecedented clarity and sensibility [24,25]. We found that following HCV core antigen stimulation, a significant cytokine response could be obtained in only a minority of patients and, more importantly, that this response was IFN-γ-restricted. These findings confirm that no ‘inappropriate’ secretion of Th2-type cytokines takes place in chronically infected HCV patients and raises the possibility of a defective antigen-specific memory/effector Tcell functionality. Indeed, a recent model of T cell memory and homeostasis suggests that, on a clonal level, the memory/effector T cell population is in constant flux, with the size and functional characteristics of any given antigen-specific T clone being continuously influenced by competition with other clones [33,34]. Since antigen availability is one of the most potent influences on clonal survival, in the context of a chronic infection, such as HCV infection, with the production of great amounts of antigen one would expect to find almost universal CD4 + memory/effector cell reactivity. Moreover, it is important to emphasize that the ability of the immune system to mount a protective CD4 + effector response is not only dependent on the number of antigen-specific memory T cells present, but also on the functional phenotype of these cells. We have demonstrated that the HCV-reactive CD4 + cells in HCV patients showed a polarized IFN-γ response with a lack of IL-2 production. It is possible that the lack of IL-2 production may compromise the overall effector response limiting, for example, recruitment, differentiation, and expansion of CD8 + effector T cells or natural killer cells. Interestingly, Lechmann et al. [35] have recently shown that patients with persistent HCV viremia and chronic liver disease have less PBMC displaying IFN-γ and IL-2 responses to HCV core antigen than patients with self-limited infection.

In contrast to HCV core antigen stimulation, a striking Th1 cytokine response, involving CD4 +, CD8 +, ‘naive’ and ‘memory’ T cell subsets and both IFN-γ and IL-2, was observed upon mitogen stimulation in patients with respect to uninfected controls. More importantly, a Th1-type response was demonstrated in the CD4+/memory subset, which proved to be unreactive or only partially reactive (IFN-γ-restricted response) after HCV core antigen stimulation. In light of these findings it is possible to speculate that the potent mitogenic stimulus of PMA plus IO unmasked the attempt by the immune system to exploit the antiviral effects of Th1 cytokines to inhibit viral replication, even though this mechanism would be insufficient to achieve viral clearance. This would result in ongoing viral replication, escape of HCV variants, due to the high HCV mutation rate, and consequent activation of cells, such as natural killer cells, which can maintain the stimulus for Th1 differentiation of T lymphocytes by providing IFN-γ [36–38].

The existence of a relationship between chronic HCV replication and Th1 predominance was further supported by the finding of a marked decrease in the Th1 response in patients in whom the HCV-RNA titre dropped to undetectable levels following IFN-α treatment. It is conceivable that the clearance of viral load induced by IFN-α abolished the antigenic stimulus to drive a Th1 response. This could also explain the apparent contradiction that IFN-α, which has been reported to promote development of Th1 cells [39,40], induced a strong reduction of Th1 cells in vivo. Alternatively, IFN-α negatively influenced Th1 cell differentiation by blocking IL-12 production by dendritic cells as recently shown [41].

Recently, several authors have reported that the majority of liver infiltrating T cells in chronic hepatitis C produce predominantly Th1-type cytokines [42,43] and that the progressive liver injury seen in chronic HCV infection is associated with the up-regulation of intrahepatic Th1-type cytokines [43]. Here, we did not find any definite correlation between Th1-type cytokine expression and histological grading, staging or basal levels of serum ALT. The different tissues studied (liver versus peripheral blood cells), the measurement of total intrahepatic expression of cytokine mRNA versus secreted cytokines, could lead to the divergent results in these studies.

Developing new and improved therapies and vaccines against HCV infection requires greater understanding of the complex immunoregulatory mechanisms that determine protective immunity or unresponsiveness. The patterns of cytokines produced by immunocompetent cells in response to pathogens are most likely to determine the outcome of the host–pathogen interaction. Following this line of reasoning, this study does not support the hypothesis that the inability to eradicate chronic HCV infection results from either an overgrowth of Th2-orientated cells or increased production of Th2-type cytokines.

REFERENCES

- 1.EASL. International Consensus Conference on Hepatitis C. Paris 26–28 February 1999. J Hepatol. 1999;30:956–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsai SL, Liaw YF, Chen MH, Huang CY, Kuo GC. Detection of type 2–like T helper cells in hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection: implications for HCV chronicity. Hepatology. 1997;25:449–61. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diepolder HM, Zachoval R, Hoffman RM, et al. Possible mechanism involving T-lymphocyte response to non-structural protein 3 in viral clearance in acute hepatitis C virus infection. Lancet. 1995;346:1006–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91691-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Missale G, Bertoni R, Lamonaca V, et al. Different clinical behaviors of acute hepatitis C virus infection are associated with different vigor of anti-viral cell-mediated immune response. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:706–14. doi: 10.1172/JCI118842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rehermann B, Chang KM, McHutchison J, Kokka R, Houghton M, Chisari FV. Quantitative analysis of the peripheral blood cytotoxic T lymphocyte response in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1432–40. doi: 10.1172/JCI118931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rehermann B, Chang KM, McHutchison J, et al. Differential cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responsiveness to the hepatitis B and C viruses in chronically infected patients. J Virol. 1996;70:7092–102. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.7092-7102.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peano G, Menardi G, Ponzetto A, Fenoglio LM. HLA-DR5 antigen: a genetic factor influencing the outcome of hepatitis C virus infection? Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:2733–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1994.00420230126015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aikawa T, Kojima M, Onishi H, et al. HLA DRB1 and DQB1 alleles and haplotypes influencing the progression of hepatitis C. J Med Virol. 1996;49:274–8. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(199608)49:4<274::AID-JMV3>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alric L, Fort M, Izopet J, Vinel J-P, Charlet J-P, Selves J, Puel J, Pascal J-P, Duffaut M, Abbel M. Genes of the major histocompatibility complex class II influence the outcome of hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1675–81. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9352872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bukh J, Miller RH, Purcell RH. Genetic heterogeneity of hepatitis C virus. Semin Liver Dis. 1995;15:41–63. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simmonds P. Variability of hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 1995;21:570–81. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840210243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salgame P, Abrams JS, Clayberger C, et al. Differing lymphokine profiles of functional subsets of human CD4 and CD8 T cell clones. Science. 1991;254:279–82. doi: 10.1126/science.254.5029.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mosmann TR, Subash S. The expanding universe of T cell subsets. Th1, Th2 and more. Immunol Today. 1996;17:138–46. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)80606-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gazzinelli RT, Makino M, Chattopadhyay SK, et al. CD4+ subset regulation in viral infection. Preferential activation of Th2 cells during progression of retrovirus-induced immunodeficiency in mice. J Immunol. 1992;148:182–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jayaraman S, Heiligenhaus A, Rodriguez A, Soukiasian S, Dorf ME, Foster CS. Exacerbation of murine herpes simplex virus-mediated stromal keratitis by Th2 type T cells. J Immunol. 1993;151:5777–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sher A, Gazzinelli RT, Oswald IP, et al. Role of T-cell derived cytokines in the downregulation of immune responses in parasitic and retroviral infection. Immunol Rev. 1992;127:183–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1992.tb01414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott P, Kaufmann SH. The role of T-cell subsets and cytokines in the regulation of infection. Immunol Today. 1991;12:346–8. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(91)90063-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ada GL, Blanden RVCTL. immunity and cytokine regulation in viral infection. Res Immunol. 1994;145:625–9. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2494(05)80044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Del Prete G, Maggi E, Romagnani S. Human Th1 and Th2 cells: functional properties, mechanisms of regulation, and role in diseases. Laboratory Invest. 1994;70:299–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fan XG, Liu WE, Wang ZC, et al. Circulating Th1 and Th2 cytokines in patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Med Inflamm. 1998;7:295–7. doi: 10.1080/09629359890992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cacciarelli TV, Martinez OM, Gish RG, Villanueva JC, Krams SM. Immunoregolatory cytokines in chronic Hepatitis C virus infection: pre- and posttreatment with interferon alfa. Hepatology. 1996;24:6–9. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishak K, Baptista A, Bianchi L, et al. Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1995;22:696–9. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80226-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson SJ, Coleclough C. Regulation of CD4 and CD8 expression on mouse T cells: active removal from surface by two mechanisms. J Immunol. 1993;151:5123–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waldrop SL, Pitcher CJ, Peterson DM, Maino VC, Picker LJ. Determination of antigen-specific memory/effector CD4+ T cell frequencies by flow cytometry. Evidence for a novel, antigen-specific homeostatic mechanism in HIV-associated immunodeficiency. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:1739–50. doi: 10.1172/JCI119338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waldrop SL, Davis KA, Maino VC, Picker LJ. Normal human CD4+ memory T cells display broad heterogenicity in their activation threshold for cytokine synthesis. J Immunol. 1998;161:5284–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cribier B, Schmitt C, Rey D, Lang JM, Kirn A, Stoll-Keller F. Production of cytokines in patients infected by hepatitis C virus. J Med Virol. 1998;55:89–91. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199806)55:2<89::aid-jmv1>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Kossodo S, Houba V, Grau GE WHO Collaborative Study Group. Assayng tumor necrosis factor concentrations in human serum, a WHO collaborative study. J Immunol Methods. 1995;182:107–12. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cannon JG, Nerad JL, Poutsiaka DD, Dinarello CA. Measurement circulating cytokines. J Appl Physiol. 1993;75:1897–902. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.4.1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Assenmacher M, Schmitz J, Radbruch A. Flow cytometric determination of cytokines in activated murine T helper lymphocytes: expression of interleukin 10 in interferon-γ and in interleukin 4 expressing cells. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:1097–101. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Westby M, Marriot JB, Guckian M, Cookson S, Hay P, Dalgleish AG. Abnormal intracellular and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) production as HIV-1-associated markers of immune dysfunction. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;111:257–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00505.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jung T, Schauer U, HeusSeries C, Neumann C, Rieger C. Detection of intracellular cytokines by flow cytometry. J Immunol Methods. 1993;159:197–205. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(93)90158-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferrik DA, Schrenzel MD, Mulvania T, Hsieh B, Ferlin WG, Lepper H. Differential production of interferon-γ and interleukin-4 in response to Th1- and Th2-stimulating pathogens by γδ T cells in vivo. Nature. 1995;373:255–7. doi: 10.1038/373255a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Butcher EC, Picker LJ. Lymphocyte homing and homeostasis. Science. 1996;272:60–6. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Selin LK, Vergilis K, Welsh RM, Nahill SR. Reduction of otherwise remarkably stable virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte memory by heterologous viral infections. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2489–99. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.6.2489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lechman M, Woitas RP, Langhans B, et al. Decreased frequency of HCV core-specific peripheral blood mononuclear cells with type 1 cytokine secretion in chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 1999;31:971–8. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80307-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seder RA, Paul WE. Acquisition of lymphokine-producing phenotype by CD4+ T cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:635–73. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.003223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trinchieri G, Wysocka M, D'Andrea A, et al. Natural killer cell stimulatory factor (NKSF) or interleukin 12 is a key regulator of immune response and inflammation. Prog Growth Factor Res. 1992;4:355–68. doi: 10.1016/0955-2235(92)90016-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trinchieri G. Biology of natural killer cells. Adv Immunol. 1989;47:187–96. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(08)60664-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brinkmann V, Geiger T, Alkan S, Heusser CH. Interferon α increases threfrequency of interferon gamma-producing. Cd4+ T Cells J Exp Med. 1993;178:1655–62. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.5.1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parronchi P, De Carli M, Manetti R, et al. IL-4 and IFN (alpha and gamma) exert opposite regulatory effects on the development of cytolytic potential by Th1 or Th2 human T cell clones. J Immunol. 1992;149:2977–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McRae BL, Semnai RT, Hayes MP, van Seventer GA. Type I IFNs inhibit human dendritic cell IL-12 production and Th1 cell development. J Immunol. 1998;160:4298–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bertoletti A, D'Elios MM, Boni C, et al. Different cytokines profiles of intrahepatic T cells in chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:193–9. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70235-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Napoli J, Bishop A, McGuinnes PH, Painter DM, McCaughan GW. Progressive liver injury in chronic hepatitis C infection correlates with increased intrahepatic expression of Th1-associated cytokines. Hepatology. 1996;24:759–65. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]