Abstract

Epithelial cells are positioned in close proximity to endothelial cells. A non-contact coculture system was used to investigate whether colonic epithelial cells activated with various cytokines are able to provide signals that can modulate ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression on endothelial cells. Coculture of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) and human microvascular endothelial cells (HMEC-1) with TNF-α/IFN-γ-stimulated human colon epithelial cell lines led to a significant up-regulation of endothelial ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression. Increased ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression by endothelial cells was accompanied by an increase in endothelial cell NF-κB p65 and NF-κB-DNA-binding activity. Inhibition of endothelial NF-κB activation using the proteosome inhibitors MG-132 and BAY 11–7082 resulted in a significant decrease of ICAM-1 expression, indicating an important role for NF-κB in this response. This cross-talk may represent a biological mechanism for the gut epithelium to control the colonic inflammatory response and the subsequent immune cell recruitment during inflammation.

Keywords: Caco-2, HUVEC, HMEC-1, TNF-α, IFN-γ

Introduction

The epithelium of the gastrointestinal tract serves as a physical barrier to microorganisms and potentially toxic compounds present in the lumen and as the frontier of the mucosal immune system [1–3]. Epithelial cells are positioned in close proximity to various cell types, which places them in the unique position of providing signals to neighbouring cells located in the underlying mucosa, e.g. endothelial cells [4,5], thereby possibly influencing the immunological response of the gut.

The intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and the vascular adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) mediate leucocyte adhesion to endothelial cells [6,7]. A major determinant of the relative contribution of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 to the recruitment of leucocytes in a given pathological condition is the density of expression of these CAMs on the surface of endothelial cells. Studies performed on monolayers of cultured endothelial cells have shown that ICAM-1 and, to a much lesser extent, VCAM-1 are constitutively expressed on the surface of these cells [6,7]. Activation of cultured endothelial cells with proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β increases ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression [8]. In vivo studies looking at the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease showed an elevated expression of ICAM-1 and/or VCAM-1 paralleling the degree of inflammation [9–12]. Using this elevated expression as a therapeutic target a murine-specific ICAM-1 antisense oligonucleotide treatment was effective in preventing and reversing dextrane sulphate sodium-induced colitis in mice [13] and ICAM-1 antisense oligonucleotide treatment was found to be of benefit in steroid dependent Crohn's disease [14].

Several studies have provided evidence that the transcriptionfactor nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) is involved in the rapid induction of these adhesion molecules during immune and inflammatory responses [15–17]. Recent evidence indicates that the ICAM-1 promotor is dependent on p65 homodimers that bind to a variant kappa B site in cytokine-activated endothelial cells [16,18]. The dependence of cytokine-induced ICAM-1 expression on NF-kappa activation is supported by data showing that antioxidant inhibitors of NF-κB, such as pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate, dramatically attenuate ICAM-1 gene expression [19]. Inhibitors that block the proteosomal degradation of IκB lead to decreased nuclear accumulation of NF-κB and the subsequent abrogation of TNF-α-induced expression of E-selectin, VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 on endothelial cells [20].

In the present study, we investigated whether coculture with activated colonic epithelial cells altered the expression of the adhesion molecules ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 in a human microvascular endothelial cell line and in primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells and we examined the role of NF-κB on ICAM-1 expression in endothelial cells. This study shows that activated colonic epithelial cells are able to directly enhance the expression of leucocyte adhesion molecules through the NF-κB signalling pathway. By using TNF-α-blocking antibodies we found that TNF-α is one of the canditates responsible for this epithelial–endothelial communication.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Human recombinant IFN-γ and TNF-α were obtained from Promega (Madison, WI, USA). Mouse-anti‐human-NF-κB p65 antibody was obtained from Boehringer Mannheim (Mannheim, Germany), mouse-anti‐human ICAM-1 and F(ab′)2 rabbit-antimouse IgG FITC from Serotec (Oxford, UK), mouse-anti‐human VCAM-1 from Cymbus Biotechnology (Chandlers Ford, Hants, UK), mouse-anti‐human TNF-α and mouse-anti‐human IL-1β from R&D Systems (Wiesbaden, Germany), Cy3-conjugated goat-anti‐rabbit IgG from Jackson Immuno Research (West Grove, PA, USA), sheep-anti‐mouse and goat-anti‐rabbit IgG peroxidase from Amersham (Buckinghamshire, UK) and rabbit-anti‐human von Willebrand factor from Sigma (St Louis, MO, UK). Digoxigenin-labelled oligonucleotides recognizing a NF-κB DNA consensus sequence were purchased from Biometra (Goettingen, Germany). BAY 11–7082 (3-[(4-methylphenyl) sulphonyl]-2-propenenitril), NF-κB SN50 and MG-132 (carbobenzoxy-l-leucyl-l-leucinal) were from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA, USA).

Cells and cell cultures

The human colon carcinoma cell lines Caco-2 (German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures, Department of Human and Animal Cell Cultures, Braunschweig, Germany) was cultured in minimal essential medium (MEM) (Gibco BRL, Paisley) containing 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 1 mm l-glutamine. Cells were cultured with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). The human microvascular cell line HMEC-1 was cultured in MCDB-131 (Gibco BRL, Paisley) containing 10 ng/ml endothelial growth factor (EGF), 1·0 µg/ml hydrocortisone, 1 mm l-glutamine, 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 10% FCS. HUVECs were isolated from umbilical cords. The umbilical vein was cannulated and incubated with 1 mg/ml collagenase type I (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) and 6 mg/ml dispase type II (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) for 20 min at 37°C. Cells were seeded into collagen-coated six-well tissue culture plates (Greiner) in endothelial cell growth medium supplemented with 2% FCS, 0·1 ng/ml EGF, 1·0 ng/ml bFGF, 1·0 µg/ml hydrocortisone, gentamycin/amphotericin B and Supplement Mix C-39215 (PromoCell). Cells were used at passage 4 and von Willebrand staining (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) was used to confirm the isolation of endothelial cells. To obtain polarized epithelial cell monolayers, Caco-2 cells were grown to confluence on the upper side of collagen-coated transwell inserts (0·4 µm pore size; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The formation of tight junctions was functionally assessed by measurements of electrical resistance across monolayers by using a Millicell electrical resistance system (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). The electrical resistance of stimulated monolayers in the experiments reported here ranged from 350 to 450 Ω per cm2 after subtraction of resistance across a cell-free filter. Separate from the epithelial cells, endothelial cells were plated and grown to confluence in the lower chamber of six-well culture plates. Before coculture, some epithelial cells were treated with TNF-α (50 ng/ml) (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) alone or in combination with IFN-γ (50 ng/ml) (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) for 1 h. To avoid the problem of possible cytokine carryover cytokines were only added to the apical side of the epithelial cell monolayer, and epithelial cells were washed at least three times with PBS — apical and basolateral sides separately to prevent carryover through the pipette — before the inserts were transferred to a new six-well culture plate containing the endothelial cells. In some experiments endothelial cells were pretreated with different NF-κB inhibitors before coculture. Viability of freshly isolated endothelial cells was assessed by trypan blue exclusion and was ≥ 95%.

Flow cytometry

Endothelial cells were harvested with 0·25% trypsin 1 mm EDTA for 30 s. Cells 1 × 106 were incubated in 100 µl FACS buffer (0·1% BSA, 10 mm NaN3 in PBS) with 100 ng mouse-antihuman ICAM-1 or 20 ng mouse-antihuman VCAM-1 for 1 h at RT. After washing 100 µl of FITC conjugated F(ab′)2 rabbit-antimouse IgG, diluted 1/200 in FACS buffer, were added and cells were incubated for 1 h at RT, and then analysed by flow cytometry.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

Nuclear extracts were prepared using a modified protocol of Schreiber et al. [21]. Briefly, cells were washed with PBS and scraped from six-well plates in ice-cold 300 µl lysis buffer A (10 mm HEPES, pH 7·9, 10 mm KCl, 0·1 mm EDTA, 0·1 mm EGTA, 2 mm DTT, 1 mm Na2MoO4, Boehringer Complete proteases). Cells were allowed to swell on ice for 5 min before 15 µl of 20% NP-40 were added. Cell fragments were pelleted, the supernatant (cytosolic extract) was saved and the pellet resuspended in 150 µl/well buffer B (10 mm HEPES, pH 7·9, 10 mm KCl, 0·1 mm EDTA, 0·1 mm EGTA, 2 mm DTT, 1 mm Na2MoO4, 400 mm NaCl, 1% NP-40, Boehringer Complete proteases), the samples rotated for 15 min at 4°C and centrifuged for 5 min at 14000 r.p.m. The supernatant (nuclear extract) was stored at −20°C until use. Nuclear protein-DNA binding studies were carried out for 15 min at RT in a 20-µl reaction volume containing 20 mm HEPES, pH 7·6, 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm (NH4)2SO4, 1 mm DTT, 0·2% Tween20, 30 mm KCl, 1 µg poly d(I-C), 0·1 µg poly l-lysine, 1 fmol digoxigenin-labelled DNA probe and 5 µg nuclear protein. Gel electophoresis was carried out using a native 6% polyacrylamide gel. A DNA probe was prepared by annealing the two consensus oligonucleotides, which were labelled at the 5′ end with digoxigenin (Biometra, Mannheim, Germany): (1) 5′-AGT TGA GGG GAC TTT CCC AGG C-3′; and (2) 3′-TCA ACT CCC CTG AAA GGG TCC G-5′. A 6% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel was used for electrophoretic separation. DNA probes bound to NF-κB were retarded, whereas unbound DNA probes were not. After blotting to a membrane, labelled oligonucleotides were detected by alkaline phophatase antidigoxigenin (Fab)2 fragments (Boehringer Mannheim).

P65 Immunoblotting

After removal of medium, the cells were washed and whole cell extracts were prepared by lysing the cells in 50 mm HEPES, pH 7·5, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, pH 8·0, 10% glycerine, 0·1% Triton X-100. Total protein concentration was assessed in a small aliquot of sample with the modified Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad, Muenchen, Germany). 35 µl cell lysate (30 µg total protein) in 1× Laemmli buffer were separated on a 7·5% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (0·2 A, 120 min; transfer buffer 48 mm Tris-base, 39 mm glycin, 0·0375% SDS (w/v), 20% methanol) after which the membrane was placed into blocking buffer (NET 0·2% gelatin) for 1 h at RT and the membrane was incubated with mouse-antihuman-NF-κB p65 antibody (dilution 2·5 µg/ml). Membranes were washed in NET and incubated with peroxidase-conjugated-antimouse Ig (dilution 1:10000) for 1 h at RT on a shaker. Immunoreactive NF-κB p65 was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL detecting kit, Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK) and bands were quantified by densitometry.

Results

Flow cytometric analysis of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression on HMEC-1 cells

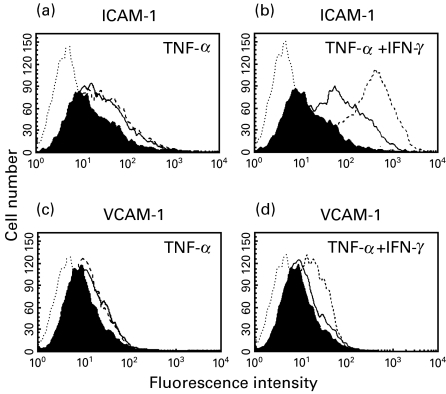

We first analysed the expression of the adhesion molecules ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 on endothelial cells during coculture with colonic epithelial cells. For this purpose, Caco-2 cells were plated on transwell inserts whereas endothelial cells were plated on the bottom of the basal chamber. In order to induce a proinflammatory response, the Caco-2 cells were incubated with two proinflammatory cytokines, TNF-α and IFN-γ, prior to coculture with endothelial cells. While IFN-γ itself is not made by intestinal epithelial cells [22], it is a potent inducer of inflammatory signalling. After different timepoints of coculture HMEC-1 cells were harvested by trypsin/EDTA and binding of primary antibody to the cell surface was detected using a FITC-conjugated secondary antibody. As shown in Fig. 1, TNF-α activated colonic epithelial cells led to a significant, time-dependent increase of ICAM-1 (median intensity fluorescence (MIF) 26·42 at 16 h compared to 12·86 for control) (Fig. 1a) and VCAM-1 (MIF 11·97 at 16 h compared to 8·66 for control) (Fig. 1c) expression by endothelial cells. The expression of ICAM-1 (MIF 339·8 at 16 h) (Fig. 1b) and VCAM-1 (MIF 18·43 at 16 h) (Fig. 1d) was increased further when endothelial cells were cocultured with TNF-α/IFN-γ-treated epithelial cells. In two of the experiments performed, endothelial cells that were either cocultured with unstimulated or cytokine-activated Caco-2 cells were counted at the end of the coculture period. No significant difference in cell numbers was observed indicating that the observed increased CAM expression was due to an up-regulation of CAM cell surface expression rather than due to differences in endothelial cell proliferation. Similar results were seen for HUVEC cells (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Flow cytometric analysis of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression on HMEC-1 cells. Cytokine-activated Caco-2 cells led to a significant increase of ICAM-1 (a, b) and VCAM-1 (c, d) expression on HMEC-1. Confluent Caco-2 cells in transwell inserts were incubated for 1 h with TNF-α (50 ng/ml) (a, c) or a combination of IFN-γ (50 ng/ml) and TNF-α (50 ng/ml) (b, d) and washed extensively before HMEC-1 cells were added to the basal chamber. ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 on HMEC-1 were detected by flow cytometry 4 h (solid lines) or 16 h (dashed lines) after start of coculture. The shaded area represents ICAM-1 (a, b) and VCAM-1 (c, d) staining on HMEC-1 cells cocultured with untreated epithelial cells. The area outlined by the dotted line represents the secondary antibody control. Representative results from one of three experiments are shown.

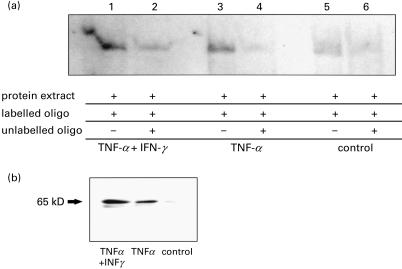

Effect of coculture with Caco-2 cells on NF-κB activity in HUVECs

To assess the signal transduction pathways that lead to enhanced adhesion factor expression we examined NF-κB activity in nuclear extracts of endothelial cells cocultured with epithelial cells. Caco-2 cells were treated with TNF-α (50 ng/ml) alone or in combination with IFN-γ (50 ng/ml) for 1 h before coculture with HUVECs. HUVEC nuclear cell extracts were prepared after 2 h of coculture and DNA-binding activity to a NF-κB-specific oligonucleotide was analysed. Compared with NF-κB activity in HUVECs cocultured with untreated Caco-2 cells (Fig. 2a, lane 5) coculture with TNF-α pretreated Caco-2 cells resulted in a significant increase of NF-κB binding activity in HUVECs (Fig. 2a, lane 3). The induction was even stronger when HUVECs were cocultured with TNF-α/IFN-γ pretreated Caco-2 epithelial cells (Fig. 2a, lane 1). The specificity of NF-κB DNA binding induced by activated Caco-2 cells was confirmed in competition experiments using a 100-fold molar excess of unlabelled oligonucleotide, which led to inhibition of NF-κB binding activity (Fig. 2a, lanes 2, 4 and 6). In accordance with these data, using an antibody that recognizes an epitope overlapping the nuclear location signal of the p65 subunit and therefore selectively stains the activated form of NF-κB, we found increased expression of the activated form of NF-κB p65 in total protein extracts of HUVECs by immunoblotting when coculturing the endothelial cells with pretreated Caco-2 cells compared to coculture with untreated Caco-2 cells (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Effect of coculture with Caco-2 cells on NF-κB activity on HUVECs. Activated Caco-2 cells led to an increase of NF-κB activity in HUVECs. Caco-2 cells were incubated with TNF-α (50 ng/ml) and IFN-γ (50 ng/ml) or TNF-α (50 ng/ml) for 1 h and washed before addition of HUVECs to the basal chamber. Co-cultures were performed for 2 h. NF-κB binding activity in endothelial cells was assessed by EMSA using nuclear extracts. A representative immunoblot showing expression of the activated NF-κB p65 in total protein extract under the same set of conditions is shown in Fig. 2b. Representative examples of X-ray films are shown.

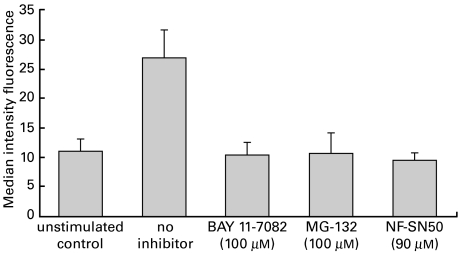

Effect of NF-κB inhibition on Caco-2 cell induced ICAM-1 expression on HUVECs

In order to evaluate whether the increased expression of ICAM-1 in endothelial cells induced by TNF-α-activated Caco-2 cells is regulated through the NF-κB signalling cascade, HUVECs were preincubated prior to coculture for 1 h with the cell permeable SN50 peptide that inhibits nuclear translocation of NF-κB active complex into the nucleus [23], the cell-permeable proteasome inhibitor MG-132 (carbobenzoxy-l-leucyl-l-leucyl-l-leucinal) that inhibits NF-κB activation, or BAY 11–7082 (3[(4-methylphenyl) sulphonyl]-2-propenenitrile) that selectively and irreversibly inhibits the TNFα-inducible phosphorylation of IκB-α thereby resulting in decreased activation of NF-κB [24]. For the inhibition studies Caco-2 cells were stimulated with TNF-α (50 ng/ml). After 1 h preincubation of HUVECs with NF-κB-inhibitors, HUVECs were washed and cocultured with the TNF-α-stimulated Caco-2 cells for 16 h after which ICAM-1 expression on HUVECs was measured by flow cytometry. Co-culture with TNF-α-activated Caco-2 cells led to an increase of endothelial ICAM-1 expression from MIF of 11·3 for coculture with unstimulated Caco-2 cells to MIF of 27·1 (Fig. 3). Endothelial inhibition of the NF-κB signalling pathway with BAY 11–7082, MG-132 and the SN50 peptide completely prevented the Caco-2 cell induced up-regulation of endothelial ICAM-1 (MIF 10·5, 10·9, 9·7) reaching a maximum at 100 µm for MG-132 and BAY 11–7082, and at 90 µm for SN50, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Effect of NF-κB inhibition on Caco-2 cell induced ICAM-1 expression on HUVECs. Confluent Caco-2 cells in transwell inserts were incubated for 1 h with TNF-α (50 ng/ml) or left unstimulated as control, while HUVEC cells were pretreated with the proteasome inhibitors BAY 11–7082 (100 µm), MG-132 (100 µm), NF-κB SN50 (90 µm) or medium alone for 1 h after which the two cell lines were cocultured for 16 h. HUVEC cells were removed following 16 h of coculture and surface ICAM-1 expression was measured by flow cytometry. Values are expressed as means ±s.e.m. of triplicate cultures from a representative experiment.

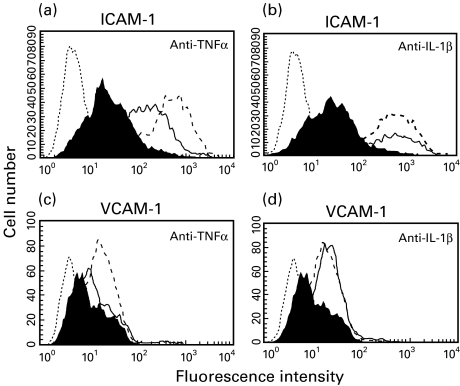

Effect of IL-1β and TNF-α neutralization on Caco-2 cell induced ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression in HUVECs

To gain further knowledge on the transmitters responsible for the above described cell–cell interaction we focused our studies on the cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α using antibodies to neutralize their effect. Caco-2 cells were treated with TNF-α (50 ng/ml) and IFN-γ (50 ng/ml) for 1 h before coculture with HUVECs was started. At the initiation of coculture, cytokine antibodies were added to the lower chamber. As shown in Fig. 4, increased ICAM-1 membrane expression on endothelial cells caused by activated Caco-2 cells was decreased by anti-TNF-α after addition of 10 µg/ml (MIF 107·5 with, MIF 327·8 without antibody) (Fig. 4a). A further increase of the antibody concentration did not lead to any further decrease of the endothelial ICAM-1 expression (data not shown). Inhibiting the bioactivity of IL-1β using the specific antibody against this cytokine had no significant effect on the increased endothelial ICAM-1 expression caused by TNF-α activated Caco-2 cells (MIF 294·3 with, MIF 352·3 without antibody) (Fig. 4b). Similar results were found for VCAM-1 expression using anti-TNF-α (MIF 12·9 with, MIF 17·8 without antibody) (Fig. 4c) and anti-IL-1β (MIF 21·3 with, 18·4 without antibody) (Fig. 4d). To check the ability of the TNF-α antibody to block TNF-α bioactivity, HUVECs were stimulated with TNF-α (50 ng/ml) for 16 h. Addition of 10 µg/ml of TNF-α antibody 1 h prior to TNF-α stimulation led to a complete inhibition of TNF-α-induced ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 up-regulation (data not shown). The same experiment was performed for the IL-1β antibody, respectively, with similar results.

Fig. 4.

Effect of IL-1β and TNF-α neutralization on Caco-2 cell induced ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression on HUVECs. Neutralization of the TNF-α bioactivity led to a dose-dependent partial decrease of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression on HUVECs, while neutralizing IL-1β had no significant effect on the adhesion factor expression. Caco-2 cells were cultured to confluence in transwell inserts, incubated for 1 h with TNF-α (50 ng/ml) and IFN-γ (50 ng/ml) and washed extensively before coculture with HUVECs was started. At the starting point of coculture antibodies against TNF-α (solid lines; a, c) or IL-1β (solid lines; b, d) were added to the lower chamber (10 µg/ml). ICAM-1 (a, b) and VCAM-1 (c, d) expression on HUVEC plasma membranes were measured by flow cytometry analysis 16 h after start of coculture. The shaded area represents ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 staining on HUVECs cocultured with untreated epithelial cells, the area outlined by the dashed line represents staining on HUVECs cocultured with activated epithelial cells without the addition of cytokine antibody. Representative results from one of three experiments are shown.

Discussion

Cell interactions that regulate the expression of cell adhesion molecules in endothelial cells under normal and inflammatory conditions are not understood. Since the intestinal epithelium is the first line of defence of the internal milieu to the external environment [1,2] and lies in proximity to a number of subepithelial celltypes, including vascular endothelium, we addressed in the present study the hypothesis that epithelial cells secrete soluble mediators which influence endothelial gene expression.

To model such cell–cell cross-talk in vitro we used a coculture system which positions endothelia in close proximity, but not in contact, with epithelial cells. In this in vitro setting cytokine-activated Caco-2 cells were able to up-regulate the expression of the two chosen endothelial target-genes ICAM-1 and VCAM-1, suggesting a possible direct interaction of intestinal epithelial cells in the recruitment of leucocytes through up-regulation of endothelial cell adhesion molecules.

As fundamental differences may exist in gene-regulation between vascular beds [25] and between immortalized cell lines and primary cells, we used HMECs, a microvascular endothelial cell line, as well as human umbilical endothelial cells as primary cells. No significant difference in change of endothelial ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression was found between the endothelial cell line HMEC-1 and primary HUVECs supporting a possible role for this in vitro process in the in vivo system.

TNF-α and IL-1β are two proinflammatory cytokines secreted by bacteria-infected human intestinal epithelial cells [22,26]. Both of these cytokines are capable of inducing endothelial expression of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 [1,7,8,27,28]. Using monoclonal antibodies against these two cytokines we showed that neutralizing the TNF-α-bioactivity led to a decrease of the Caco-2-cell-induced endothelial ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression. IL-1β, on the other hand, did not seem to function as a soluble mediator since neutralizing IL-1β bioactivity did not change the endothelial target-gene expression. The data suggest that TNF-α is one of the mediators released by Caco-2 cells. On the other hand, there has to be another mediator(s) released by Caco-2 cells since neutralizing of the TNF-α-bioactivity in this coculture system led only to a partial inhibition of the Caco-2 cell induced up-regulation of the endothelial ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression and the TNF-α-antibody primarily is able to completely inhibit the ICAM-1 and VCAM-1-inducing effect of TNF-α as tested in a HUVEC monolayer system. To avoid stimulation of endothelial ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 by the recombinant cytokines in this in vitro model, cytokines were only added to the apical side of the epithelial monolayer. After preincubation with cytokines, epithelial cells were extensively washed prior to start of coculture and only data from cocultures with an electrical resistance across the epithelial monolayer of more than 350 Ω after stimulation were included.

TNF-α is a major cytokine involved in activation of transcription factor NF-κB. TNF-α binds to its receptors and initiates second messenger and signalling cascades [29], resulting in the activation of the IκB kinase complex. Read et al. have shown that peptide aldehyde inhibitors that block the proteolytic activity of the proteasomal degradation pathway for IκB lead to an inhibition of TNF-α-induced cell surface expression of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 on endothelial cells [20]. Similar results were published recently for the role of NF-κB in ICAM-1 gene regulation in TNF-α-stimulated IEC-6 rat intestinal epithelial cells [30] and infection of HUVECs with Trypanosoma cruzi activated NF-κB and induced adhesion molecule expression [31]. The present work demonstrates that TNF-α/IFN-γ activated epithelial cells led to an increase of the active form of NF-κB p65 in extracts of endothelial cells as well as to an increase of NF-κB shift in electrophoretic-mobility-shift-assays of endothelial nuclear extract. Furthermore, we were able to show that inhibitors that block the proteolytic activity of the proteosomal degradation pathway for IκBα as well as a peptide that inhibits the translocation of the NF-κB active complex into the nucleus led to decreased nuclear accumulation of NF-κB (data not shown) and the complete abrogation of Caco-2-cell-induced cell-surface expression of ICAM-1 on endothelial cells. The heightened activation of NF-κB could therefore be a major regulator of epithelial–endothelial cell–cell cross-talk, possibly leading to an increased infiltration of leucocytes into the mucosal tissue during inflammation by up-regulating the expression of adhesion molecules. These data show that the Caco-2-cell produced factors exert their effect on endothelial ICAM-1 expression through activation of the NF-κB signalling pathway. The complete inhibition of the Caco-2-cell induced increase in endothelial ICAM-1 expression by blocking the NF-κB signal transduction, on one hand, and the only partial inhibition of the Caco-2-induced endothelial ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression by neutralizing the TNF-α bioactivity, on the other hand, indicates that the yet to be identified other soluble mediator(s) also signals through NF-κB.

Since in this in vitro set of experiments only colonic epithelial cells that were stimulated with proinflammatory cytokines were able to induce adhesion molecule expression, the interaction between epithelial and endothelial cells may be biologically more relevant during inflammatory reactions of the intestinal mucosa.

In conclusion, our data suggest that epithelial–endothelial cell interactions may have important immunological consequences in vivo by positively regulating the expression of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 that are important in inflammation. If this is the case, the colonic epithelium activated by bacterial pathogens or by proinflammatory cytokines produced from subepithelial localized macrophages may activate the endothelium to modulate the host inflammatory response and/or to orientate the immune response.

Acknowledgments

We thank I. Klingenhagen and E. Weber for expert technical help and M. F. Kagnoff and L. Eckmann for critical review of the manuscript. This work was supported by the SFB 293 (TP B6).

References

- 1.Huang H, Calderon M, Berman JW, et al. Infection of endothelial cells with Trypanosoma cruzi activates NF-κB and induces vascular adhesion molecule expression. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5434–40. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.10.5434-5440.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kagnoff MF, Eckmann L. Epithelial cells as sensors for microbial infection. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:6–10. doi: 10.1172/JCI119522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kucharzik T, Lugering N, Pauels HG, Domschke W. IL-4, IL-10 and IL-13 down-regulate monocyte-chemoattracting protein-1 (MCP-1) production in activated intestinal epithelial cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;111:152–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00481.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blume ED, Taylor CT, Lennon PF, Stahl GL, Colgan SP. Activated endothelial cells elicit paracrine induction of epithelial chloride secretion. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1161–72. doi: 10.1172/JCI3465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lugering N, Kucharzik T, Gockel H, Sorg C, Stoll R, Domschke W. Human intestinal epithelial cells down-regulate IL-8 expression in human intestinal microvascular endothelial cells; role of TGF-β1. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;114:377–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00718.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlos TM, Harlan JM. Leukocyte–endothelial adhesion molecules. Blood. 1994;84:2068–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panes J, Granger DN. Leukocyte–endothelial cell interactions: molecular mechanisms and implications in gastrointestinal disease. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1066–90. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pober JS, Gimbrone Ma, Jr, Lapierre LA, et al. Overlapping patterns of activation of human endothelial cells by interleukin-1, tumor necrosis factor, and immune interferon. J Immunol. 1986;137:1893–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Binion DG, West GA, Ina K, Ziats NP, Emancipator SN, Fiocchi C. Enhanced leukocyte binding by intestinal microvascular endothelial cells in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1895–907. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9178682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koizumi M, King N, Lobb R, Benjamin C, Podolsky DK. Expression of vascular adhesion molecules in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:840–7. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90015-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malizia G, Calabrese A, Cottone M, et al. Expression of leukocyte adhesion molecules by mucosal mononuclear phagocytes in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:150–9. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90595-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakamura S, Ohtani H, Watanabe Y, et al. In situ expression of the cell adhesion molecules in inflammatory bowel disease: evidence of immunologic activation of vascular endothelial cells. Lab Invest. 1993;69:77–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bennett CF, Kornbrust D, Henry S, et al. An ICAM-1 antisense oligonucleotide prevents and reverses dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;280:988–1000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yacyshyn BR, Bowen-Yacyshyn MB, Jewell L, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of ICAM-1 antisense oligonucleotide in the treatment of Crohn‘s disease. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1133–4298. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70418-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baeuerle PA, Baltimore D. NF-kappa B: ten years after. Cell. 1996;87:13–20. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ledebur HC, Parks TP. Transcriptional regulation of the intercellular adhesion molecule-1 gene by inflammatory cytokines in human endothelial cells: essential roles of a variant NF-κB site and p65 homodimers. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:933–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.2.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roebuck KA, Rahman A, Lakshminarayanan V, Janakidevi K, Malik AB. H2O2 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha activate intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) gene transcription through distinct cis-regulatory elements within the ICAM-1 promotor. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:18966–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.32.18966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jahnke A, Johnson JP. Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) is synergistically activated by TNF-α and IFN-γ responsive sites. Immunobiology. 1995;193:305–14. doi: 10.1016/s0171-2985(11)80559-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawai M, Nishikomori R, Jung EY, et al. Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate inhibits intercellular adhesion molecule-1 biosynthesis induced by cytokines in human fibroblasts. J Immunol. 1995;154:2333–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Read MA, Neish AS, Luscinskas FW, Palombella VJ, Maniatis T, Collins T. The proteasome pathway is required for cytokine-induced endothelial–leukocyte adhesion molecule expression. Immunity. 1995;2:493–506. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schreiber E, Matthias P, Muller MM, Schaffner W. Rapid detection of octamer binding proteins with ‘mini-extracts’ prepared from a small number of cells. Nucl Acids Res. 1989;17:6419. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.15.6419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jung HC, Eckmann L, Yang SK, et al. A distinct array of proinflammatory cytokines is expressed in human colon epithelial cells in response to bacterial invasion. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:55–65. doi: 10.1172/JCI117676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin YZ, Yao SY, Veach RA, Torgerson TR, Hawiger J. Inhibition of nuclear translocation of transcription factor NF-kappaB by a synthetic peptide containing a cell membrane-permeable motif and nuclear localization sequence. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:14255–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.24.14255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pierce JW, Schoenleber R, Jesmok G, et al. Novel inhibitors of cytokine-induced IkappaBalpha phosphorylation and endothelial cell adhesion molecule expression show anti-inflammatory effects in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21096–103. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Panes J, Perry MA, Anderson DC, et al. Regional differences in constituitive and induced ICAM-1 expression in vivo. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:1955–64. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.6.H1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eckmann L, Stenson WF, Savidge TC, et al. Role of intestinal epithelial cells in the host secretory response to infection by invasive bacteria. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:296–309. doi: 10.1172/JCI119535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dustin ML, Rothlein R, Bhan AF, Dinarello CA, Springer TA. A natural adherence molecule (ICAM-1): induction by IL-1 and IFN-γ, tissue distribution, biochemistry, and function. J Immunol. 1986;137:245–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swerlick RA, Lee KH, Li LJ, Sepp NT, Caughman SW, Lawley TJ. Regulation of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 on human dermal microvascular endothelial cells. J Immunol. 1992;149:698–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith CA, Farrah T, Goodwin RG. The TNF receptor superfamily of cellular and viral proteins: activation, costimulation, and death. Cell. 1994;76:959–62. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90372-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jobin C, Hellerbrand C, Licato LL, Brenner DA, Sartor RB. Mediation by NF-κB of cytokine induced expression of intracellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) in an intestinal epithelial cell line, a process blocked by proteasome inhibitors. Gut. 1998;42:779–87. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.6.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang GT, Eckmann L, Savidge TC, Kagnoff MF. Infection of human intestinal epithelial cells with invasive bacteria upregulates apical intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) expression and neutrophil adhesion. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:572–83. doi: 10.1172/JCI118825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]