Abstract

Ro ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) are autoantigens that result from the association of a 60-kDa protein (Ro60) with a small RNA (hY1, hY3, hY4 or hY5 in humans, mY1 or mY3 in mice). Previous studies localized Ro RNPs to the cytoplasm. Because Ro RNPs containing hY5 RNA (RohY5 RNPs) have unique biochemical and immunological properties, their intracellular localization was reassessed. Subcellular distribution of mouse and human Ro RNPs in intact and hY-RNA transfected cells was assessed by immunoprecipitation and Northern hybridization. Human RohY1–4 RNPs as well as murine RomY1, mY3 RNPs are exclusively cytoplasmic. Ro RNPs containing an intact hY5 RNA, but not those containing a mutated form of hY5 RNA, are found in the nuclear fractions of human and mouse cells. RohY5 RNPs are stably associated with transcriptionally active La protein and are known to associate with RoBPI, a nuclear autoantigen. Our results demonstrate that RohY5 RNPs are specifically present in the nucleus of cultured human and murine cells. The signal for nuclear localization of RohY5 RNPs appears to reside within the hY5 sequence itself. In conclusion, we suggest that the unique localization and interactions of primate-specific RohY5 RNPs reflect functions that are distinct from the predicted cytoplasmic function(s) of more conserved Ro RNPs.

Keywords: anti-Ro antibodies, autoantigens, cytolocalization, ribonucleoprotein, Ro antigen, transfection

Introduction

Ro ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) are the major RNP autoantigen recognized by sera from patients with connective tissue diseases [1,2]. In contrast, anti-Ro RNP antibodies are rarely if ever produced in spontaneously arising autoimmune mouse models [3]. Intra- and intermolecular epitope spreading observed in autoimmune patients strongly suggest that the immunizing antigen responsible for anti-Ro production consists of human Ro [4,5]. While the mechanisms leading to autoantibody production against the Ro particles are not yet defined, a role for structural or functional characteristics of the antigen is likely.

Ro RNPs consist of one small RNA of the Y (cYtoplasmic) family (hY1, hY3, hY4, hY5 in man; mY1 and mY3 in mice) associated with a 60-kDa protein (Ro60) [6]. Ro RNPs containing the hY5 RNA (RohY5 RNPs) are recent evolutionary additions since they are only present in primates [7,8]. Human Ro RNPs have discrete biochemical properties depending on the hY RNA they contain, and human autoantibodies specifically target RohY5 RNPs [7,9]. Ro60 binds to hY RNAs through a highly conserved double-stranded stem formed by basepairing between their 3′ and 5′ ends [6,10]. All previous studies localized Ro RNPs to the cytoplasm [6,11–15]. Assembly of Ro RNPs appears to occur in the nucleus, as Ro60 binding was required for the export of hY1 RNAs to the cytoplasm of Xenopus laevis oocytes through a transport mechanism shared with tRNAhis [12,16]. In this model, binding of La protein mediated nuclear retention of the hY1 RNA.

Since the localization and interactions of Ro RNPs may give clues to their functions, we reassessed their cellular distribution. Using the nucleocytoplasmic distribution of autoantigenic nuclear U1 RNP [17] and cytoplasmic tRNAhis synthetase [18] as compartmental markers, we report that hY5-containing Ro RNPs (RohY5 RNPs) fractionate with U1 RNP and therefore are nuclear components. Association of nuclear Ro antigen with La protein occurred preferentially with its unphosphorylated form. In transiently transfected NIH 3T3 mouse cells, Ro RNPs containing hY4 RNA colocalized in the cytoplasm with autologous murine Ro RNPs. However, Ro RNPs containing intact hY5 RNA were found in the nuclear fraction of transfected mouse cells but those containing the slightly mutated hY5–84′O'RNA [19] were not. These data suggest that RohY5 RNPs are retained in the nucleus, presumably through an interaction mediated by the hY5 RNA itself. We propose that the distinct properties of human RohY5 RNPs relate to specific interactions and possibly to the unique immunogenicity of Ro antigen in man.

Materials and methods

In vivo labelling of RNPs

HeLa cells were maintained at 37°C under 5% CO2 in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 60 µg/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin.

Labelling of RNAs

For long-term labelling (more than 16 h), cells (2·5 × 105/ml) were labelled with 10 µCi/ml[32P]-orthophosphate (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Baie d'Urfé QC, Canada) in 80% phosphate-free RPMI containing 10% dialysed FBS [9]. For short-term (less than 16 h) labelling, cells (2·5 × 105/ml) were labelled with 40 µCi/ml[32P]-orthophosphate in phosphate-free essential medium containing 10% dialysed FBS.

Labelling of proteins

For long-term labelling (longer than 16 h), 2·5 × 105 cells/ml were incubated with 10 µCi/ml[35S]-methionine (Amersham) in methionine-deficient medium supplemented with 20% complete medium and 10% dialysed serum. For short-term labelling, 2·5 × 105 cells/ml were incubated with 40 µCi/ml[35S]-methionine in methionine-deficient medium supplemented with 10% dialysed calf serum.

In cold chase experiments, radiolabelled cells were centrifuged at 600 g, resuspended at 2·5 × 105 cells/ml in normal serum-supplemented RPMI 1640, and incubated for various periods.

Cell fractionation

Cells were first washed twice in cold TBS and resuspended at 2 × 106/ml in cold TKB buffer (0·25 m sucrose, 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7·4, 25 mm KCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 0·5 mm CaCl2) containing 3 mm dithiothreitol (DTT), protease inhibitors (0·5 mg/l each of chymostatin, leupeptin, antipain, pepstatin) and RNase inhibitor (40 U/ml RNAguard; Amersham). Digitonin (25–40 µg/ml), a detergent with high affinity for cholesterol-rich membranes [20–22], was added and the cells were slowly agitated at 4°C for 5 min. Since the amounts of digitonin in commercial products are variable, the concentrations used were carefully adjusted with each new lot to obtain the appropriate nucleocytoplasmic distribution of U1 RNP and tRNAhis synthetase markers. Nuclei were pelleted at 1000 g for 5 min. The supernatant was clarified by centrifugation at 13 000 g for 5 min and used as the cytoplasmic fraction. After one wash in 300 µl cold TKB, nuclei were sonicated in cold NET-2 buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7·5, 150 mm NaCl, 0·05% Nonidet P-40); the soluble fraction was recovered by centrifugation at 13 000 g and used directly as the nuclear fraction.

Detection of proteins and RNAs in immunoprecipitated RNPs

Sera and antibodies

We obtained a rabbit antiserum specific for Ro60 [23,24] from Dr Mark Mamula (Yale University). In addition, we used human sera with specificities defined by comparison of their immunoprecipitating patterns with reference sera.

Immunoprecipitation

Immunoprecipitation of total, cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts was performed as described previously [9]. To ensure that immunoprecipitation was quantitative, excess amounts of antibody was used such that less than 10% of radiolabelled RNA and protein components of RNPs could still be immunoprecipitated from supernatants (data not shown). The amounts of cells used in each immunoprecipitation were normalized per µg of soluble proteins (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA, USA). Radiolabelled proteins and RNAs were visualized by fluorography or autoradiography, respectively, and quantified on a PhosphorImager running the imagequant software (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Measurements of radioactive counts in autoantigen-specific bands from PAGE-fractionated immunoprecipitates were assumed to reflect the true amounts of RNA and protein components of autoantigens present in each cellular fraction. Unlabelled nucleic acids were visualized by silver staining, and unlabelled autoantigenic proteins were identified by immunoblotting using specific antibodies and enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham) [9].

Cell transfection

Vector construction

To prevent transcription of hY cDNA inserts by RNA polymerase II, the RNA polymerase II promoter from the eukaryotic expression vector pcDNA3 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was deactivated by digestion with Bgl II and BamH I followed by ligation to yield mpcDNA3. The pUC vectors phY4 and phY5 containing genomic hY4 and hY5 DNA as well as their 5′ promoter region and some 3′ sequence were gifts from Dr Richard Maraia (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) [8,25]. The pUC vector phY4 was digested with Xba I and the resulting genomic hY4 DNA was subcloned into mpcDNA3 vector to yield plasmid pcY4. Because RNA polymerase III promoter of hY5 RNA was less efficient to drive transcription in mouse cells [8], the coding sequence of hY4 RNA in genomic hY4 DNA was replaced using PCR by the coding sequence of hY5 RNA in plasmid pcY4 to yield plasmid pcY5. Similarly, a cDNA encoding fusion hY4/5 RNA was inserted in place of the hY4 sequence in plasmid pcY4 to yield plasmid pcY4-Y5. From the 5′ to the 3′ end, fusion hY4/5 RNA consists of the hY4 RNA sequence from which the short 3′ oligouridylate (UU) tail has been deleted, a stable stem-loop linker (5′-ACAACCCCCCAAACUUCGGUUUGGG-3′) and the hY5 RNA sequence. Finally, a cDNA encoding the hY5–84′O'RNA sequence was inserted in place of the hY5 sequence in plasmid pcY5 to yield plasmid pcY5′O′. In the hY5–84′O'RNA, nucleotides (nt) 53–57 of hY5 RNA are modified from 5′-CCCAC-3′ to 5′-AAAAA-3′ to disrupt the predicted stem structure in the middle part of hY5 RNA [19].

NIH 3T3 mouse cell transfection and selection

NIH 3T3 cells were grown at 37°C under 5% CO2 in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS. Transfection was performed in incomplete RPMI 1640 with Lipofectamine according to manufacturer's instructions (GibcoBRL). Selection of transfected cells was started using 1500 µg/ml of G418 sulphate (Geneticin; GibcoBRL). Clones of transfected cells were picked and seeded in separate Petri dishes.

Northern detection of Y RNAs present in immunoprecipitated Ro RNPs

Fractionation of transfected NIH 3T3 cells and immunoprecipitation were performed as above. RNAs present in immunoprecipitated RNPs were electrotransfered to Hybond N + membranes (Amersham) and fixed by ultraviolet irradiation. [32P]-labelled antisense probes were transcribed from EcoRI linearized plasmids pTZR/hY5 and pTZR/hY4 (gifts from Dr Ger Pruijn) [15] using T7 RNA polymerase, and gel-purified as described [19]. Hybond N + membranes were prehybridized for 1 h at 42°C with hybridization buffer (5% SDS, 400 mm NaH2PO4 pH 7·2, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 50% formamide) and hybridized overnight at 50°C with the probe. Under the conditions where the hY4 and hY5 probes were used, extensive cross-reactivity between mY3, hY4 and hY5 RNAs was the rule. Under more stringent conditions, each probe hybridized only to its corresponding RNA (data not shown).

Results

Heterogeneous distribution of Ro RNPs in unlabelled HeLa cells

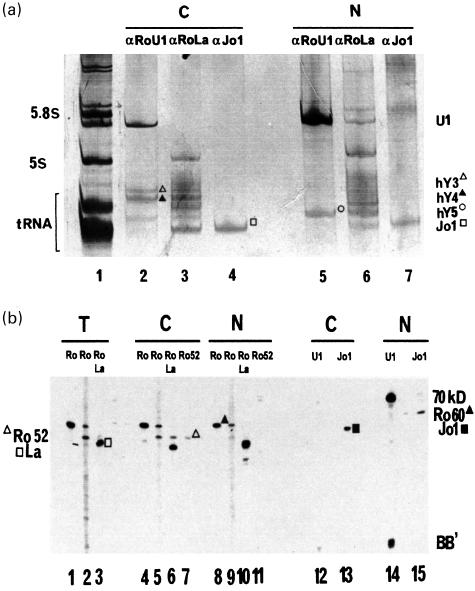

Preliminary experiments to assess the localization of autoantigenic Ro RNPs were performed using specific immunoprecipitation from unlabelled HeLa cells (Fig. 1). As expected, tRNAhis synthetase (Jo-1) was found mainly in the cytoplasmic (Fig. 1a, lane 4) relative to the nuclear fraction (lane 7), while U1 RNP was predominantly nuclear (compare lane 5 to lane 2). Unexpectedly, RohY5 RNPs were found predominantly in the nuclear fraction (lane 5) while Ro RNPs containing hY1 through hY4 RNAs (RohY1–hY4 RNPs) appeared exclusively cytoplasmic (lane 2). The La-associated RNPs appeared more abundant in the nuclear (lane 6) than in the cytoplasmic fraction (lane 3). Similarly, the distribution of the protein components of RNPs was defined by immunoblotting using specific antibodies (Fig. 1b). Control proteins associated with U1 RNP (Fig. 1b, lanes 12 and 14) and tRNAhis synthetase (lanes 13 and 15) were found predominantly in the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions, respectively. Ro52 was predominantly cytoplasmic (compare lanes 5–7 to lanes 9–11) [24]. Ro60 protein was distributed equally in both compartments (compare lanes 4, 5 and lanes 8, 9), while La protein was more abundant in the nuclear fraction (lanes 6 and 10).

Fig. 1.

Immunoprecipitation of autoantigenic RNPs from fractionated unlabeled HeLa cells. (a) RNP-associated RNAs. RNAs present in total cell extracts are shown in lane 1, the cytoplasmic fraction in lanes 2–4, and the nuclear fraction in lanes 5–7. Sera used are anti-Ro/U1 RNP in lanes 2 and 5, anti-Ro/La in lanes 3 and 6 and anti-Jo-1 in lanes 4 and 7. (b) RNP-associated proteins. Lanes 1–3 contain total cell extracts, lanes 4–7, 12 and 13 contain the cytoplasmic fraction, and lanes 8–11, 14 and 15 contain the nuclear fraction. These extracts are probed with a monospecific anti-Ro60 serum (lanes 1, 4 and 8), with an anti-Ro60/Ro52 serum (lanes 2, 5 and 9), with an anti-Ro52/La serum (lanes 3, 6 and 10), with a rabbit anti-Ro52 serum (lanes 7 and 11), with an anti-U1 RNP serum (lanes 12 and 14) and with an anti-Jo-1 serum (lanes 13 and 15). A migration anomaly in lane 15 explains the apparent discrepancy in molecular weigth between cytoplasmic and nuclear tRNAhis synthetase.

Distribution of Ro RNPs immunoprecipitated from in vivo radiolabelled HeLa cells

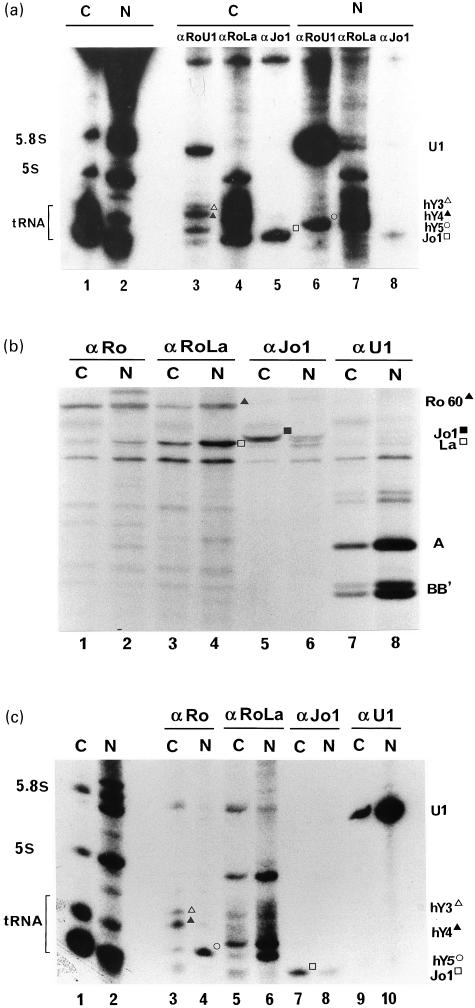

RNA and protein components from the immunoprecipitated RNPs did not radiolabel at the same rate, reflecting different half-lives of RNPs (data not shown). To obtain uniformly labelled RNPs, exponentially growing HeLa cells were radiolabelled for 40 h (i.e. approximately two cell cycles) before fractionation. In the representative experiment shown in Fig. 2, the expected nucleocytoplasmic distribution of U1 and Jo-1 RNPs was observed. For example, anti-U1 RNP antibodies immunoprecipitated less than 4% of total U1 RNA from cytoplasmic fractions (Fig. 2a, lane 3), and about 10% of the U1-specific A protein (Fig. 2b, lane 7). A small cytoplasmic pool of non-RNP associated A and C proteins was reported previously [17]. In contrast, anti-Jo-1 antibodies recovered, from the cytoplasmic fractions, more than 90% of tRNAhis and of tRNAhis synthetase present in total cell extracts (Fig. 2a, lane 5 and Fig. 2b, lane 5, respectively). Since about 5% of the cells are undergoing mitosis at any given time in exponentially growing HeLa cells, we concluded that nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions routinely contained less than 5–10% cross-contamination.

Fig. 2.

Immunoprecipitation of RNPs from in vivo radiolabelled HeLa cells. (a) RNP-associated RNAs. RNAs present in total cytoplasmic (lane 1) and nuclear (lane 2) extracts are shown. Lanes 1 and 3–5 come from the cytoplasmic fraction while lanes 2 and 6–8 come from the nuclear fraction. Sera used are anti-Ro/U1 RNP (lanes 3 and 6), anti-Ro/La (lanes 4 and 7), and anti-Jo-1 (lanes 5 and 8). (b) RNP-associated proteins. Lanes 1, 3, 5 and 7 come from the cytoplasmic fraction while lanes 2, 4, 6 and 8 come from the nuclear fraction. Sera used include the monospecific anti-Ro60 serum used in Fig. 1b (lanes 1 and 2), an anti-Ro/La serum with better immunodepleting capacity for La than for Ro60 (lanes 3 and 4), an anti-Jo-1 serum (lanes 5 and 6), and an anti-U1 RNP serum (lanes 7 and 8). (c) RNP-associated RNAs following a 24-h cold chase. RNAs present in total cytoplasmic (lane 1) and nuclear (lane 2) extracts are shown. Lanes 1 and 3, 5, 7 and 9 come from the cytoplasmic fraction while lanes 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 come from the nuclear fraction. Sera used include the monospecific anti-Ro60 serum used in Fig. 1b (lanes 3 and 4), an anti-Ro/La serum (lanes 5 and 6), an anti-Jo-1 serum (lanes 7 and 8), and an anti-U1 RNP serum (lanes 9 and 10).

Using the same cell fractions, about 90% of RohY3 and RohY4 RNPs were found in the cytoplasmic fraction (Fig. 2a, lane 3), where they appeared to be stably localized after a short labelling period (5 h; data not shown) and after a 24-h cold chase period (Fig. 2c, lane 3). The low abundance of RohY1 RNPs precluded their reproducible quantification but they also appeared to reside in the cytoplasmic fraction. The RohY5 RNPs were found predominantly in the nuclear fraction (about 85%; Fig. 2a, lane 6), where they remained after prolonged chase periods (Fig. 2c, lane 4). Cold chase experiments indicated that the nuclear localization of RohY5 RNPs was not transient and did not merely reflect delayed export. RohY5 RNPs were also found predominantly in the nuclear fractions of HL60 and MOLT-4 cell lines (data not shown).

Composition of nuclear and cytoplasmic Ro RNPs

One explanation for the unique nuclear retention of RohY5 RNPs would be some anomaly in their composition such as different hY RNA/Ro60 ratios or a more stable association with La protein.

We first examined the hY RNA to Ro60 ratio of cytoplasmic and nuclear Ro RNPs. The hY5 RNA constituted a little less than 60% of the total radioactivity incorporated in immunoprecipitated hY RNAs. After correction for differences in size of hY RNAs (hY1: 112 nt; hY3: 101 nt; hY4: 95 nt; hY5: 84 nt), the approximate molar ratios of hY5/hY4/hY3/hY1 RNAs were calculated to be about 20/9/4/less than 1. The proportions of nuclear hY RNAs and of nuclear Ro60 protein were both close to 60% (Fig. 2b, lanes 1 and 2; Table 1). No significant differences in hY RNA to Ro60 protein ratios was thus apparent between cytoplasmic and nuclear Ro RNPs.

Table 1.

Nuclear distribution of RNA and protein components of antigenic RNPs. The percentages of the cellular RNP components that were identified in the nuclear fraction are expressed as mean ratios ±s.e.m. from three distinct experiments. RNAs were [32P]-labelled and proteins were [35S]-labelled, separated in polyacrylamide gels and quantified by PhosphorImager. RNAs and proteins are listed by name. Exceptions are hYtotal which stands for the summation of all hY RNAs, La total, which represents all the RNAs associatd with La, LaRo60 which represents the La protein coprecipitated with Ro60 protein and AU1 which stands for U1 RNP-specific A protein

| Percentage nuclear % ± s.e.m. | |

|---|---|

| RNAs | |

| hY5 | 87 ± 8 |

| hY4 | 13 ± 6 |

| hY3 | 11 ± 8 |

| hYtotal | 55 ± 10 |

| tRNAhis | 15 ± 9 |

| U1 | 94 ± 6 |

| La total | 70 ± 15 |

| Proteins | |

| Ro60 | 57 ± 10 |

| LaRo60 | 92 ± 10 |

| La | 75 ± 18 |

| tRNAhis synthetase | 18 ± 10 |

| AU1 | 90 ± 8 |

We then examined the association of cytoplasmic and nuclear Ro RNPs with La protein. About 75% of La protein (Fig. 2b, lanes 3 and 4; Table 1) and of La-associated RNAs were found in the nuclear fraction (Fig. 2a, lanes 4 and 7; Table 1). Interestingly, most Ro60-associated La protein (a small but measurable fraction of cellular La) was immunoprecipitated from the nuclear rather than the cytoplasmic fraction (Fig. 2b, lanes 1 and 2). The La protein is a phosphoprotein whose activity in RNA polymerase III transcription is modulated by phosphorylation [26]. Low levels of phosphorylation of Ro60 protein have also been reported [27]. To determine whether the observed nuclear retention of RohY5 RNPs was associated with phosphorylation of Ro60 or, alternatively, of La protein associated to nuclear Ro, Ro60 and La proteins were immunoprecipitated with specific antibodies from cells radiolabelled with [32P]-orthophosphate (Fig. 3). Most phosphorylated La protein was found in the nuclear fraction (Fig. 3, lanes 4 and 6) but was not recovered with anti-Ro60 antibodies (Fig. 3, lane 2). This suggested that nuclear Ro antigen associated mainly with unphosphorylated La, its presumably active form [26]. No phosphorylated Ro60 was clearly detected (Fig. 3, lanes 1 and 2), possibly because of insufficient labelling in these exponentially growing unsynchronized cells. None the less, these data suggested that phosphorylation of Ro60 or La proteins did not explain the nuclear retention of RohY5 RNPs.

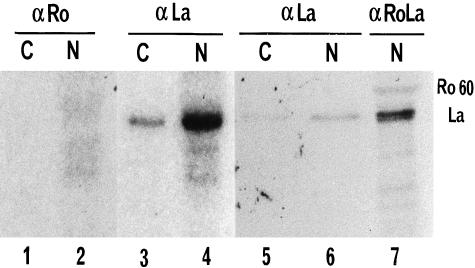

Fig. 3.

Detection by autoradiography of [32P]-labelled proteins in anti-Ro and anti-La immunoprecipitates from fractionated HeLa cells radiolabelled with [32P]-orthophosphate. Lanes 1, 3 and 5 are from the cytoplasmic fraction while lanes 2, 4 and 6 are from the nuclear fraction. Sera used include monospecific anti-Ro60 (lanes 1 and 2) and anti-Ro/La (lanes 3–6). Anti-Ro/La immunoprecipitates from [35S]-labelled HeLa cells (lane 7) are used as molecular weight markers and run in the same gel as immunoprecipitates in lanes 5 and 6. Immunoprecipitates in lanes 1–4 and those in lanes 5–7 were from 2 different experiments and were exposed on film for significantly different periods.

Expression of hY RNAs in mouse cells

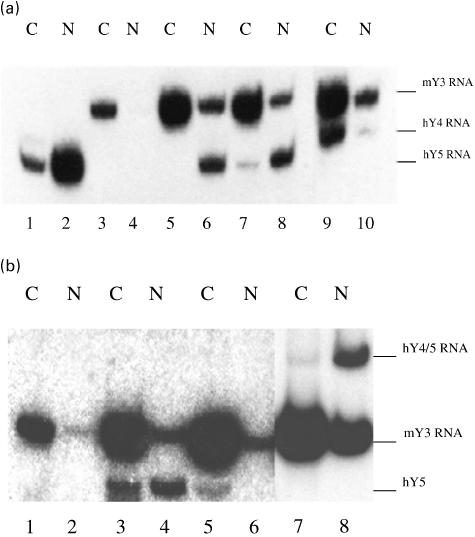

To determine whether nuclear localization of RohY5 RNPs was specific to human cells and to address the mechanisms of their unusual cellular localization, plasmids encoding hY4 and hY5 cDNAs were transiently transfected in NIH 3T3 mouse cells. The corresponding hY4 and hY5 RNAs were expressed and readily incorporated into heterologous Ro RNPs containing the murine Ro60 protein, as assessed by Northern blotting of RNAs immunoprecipitated by anti-Ro60 antibodies. Migration in urea-PAGE of hY RNAs from transfected mouse cells and HeLa cells were identical (Fig. 4), indicating that in vivo RNA polymerase III transcription yielded identical hY transcripts in mouse and human cells [8]. Ro RNPs containing hY4 RNA were found in the cytoplasmic fraction of murine cells (Fig. 4, lane 9), alongside endogenous Ro RNPs (Fig. 4a, lanes 3, 5, 7 and 9). In contrast, heterologous Ro RNPs containing hY5 RNA (Fig. 4a, lanes 6 and 8) were predominantly nuclear.

Fig. 4.

Northern blot localization of hY RNAs stably transfected in NIH 3T3 mouse fibroblast cells. (a) hY4 and hY5 RNAs. Lanes 1, 3, 5, 7 and 9 are from the cytoplasmic fraction while lanes 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 are from the nuclear fraction. All fractions are immunoprecipitated with the same anti-Ro serum. Lanes 1 and 2 are immunoprecipitates from HeLa cells that are used in trace amounts as molecular weight markers; lower amounts of hY4 RNA and lower affinity of the hY4 probe explain the weak hY4 signal in lane 1. Lanes 3 and 4 are from non-transfected NIH 3T3 cells, lanes 5–6 and 7–8 are from two distinct clones of cells transfected with hY5 RNA, and lanes 9 and 10 are from hY4-transfected cells. Under the conditions used, only the endogenous mY3 RNA hybridized with the hY4 and hY5 probes; endogenous mY1 RNA was detected with the same probes when less stringent conditions were used (data not shown). (b) Fusion hY4/5 RNA and hY5–84′O'RNA. Lanes 1, 3, 5 and 7 are from the cytoplasmic fraction and lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8 are from the nuclear fraction. All fractions are immunoprecipitated with the same anti-Ro serum. Lanes 1 and 2 are from non-transfected mouse cells, lanes 3 and 4 are from hY5-transfected cells, lanes 5 and 6 are from hY5–84′O′-transfected cells, and lanes 7 and 8 are from hY4/5-transfected cells (from a distinct experiment).

Nuclear accumulation of heterologous RohY5 RNPs in mouse cells could have resulted from their failure to interact with the mouse homologue of the export pathway of Ro RNPs [16]. Alternatively, RohY5 RNPs might be retained in nuclear fractions through specific interactions with still unknown nuclear component(s). To determine which of these mechanisms was the most likely, we transfected mouse cells with hY4/5 RNA containing the sequences of hY4 and hY5 RNAs linked in tandem by a stable stem-loop designed to minimize interactions between the two domains of the fusion RNA. As with heterologous RohY5 RNPs, murine Ro RNPs containing hY4/5 RNA (RohY4/5 RNPs) were found in the nuclear fraction (Fig. 4b, lane 8). Nuclear localization of RohY4/5 RNPs strongly suggested that the hY5 sequence contributed to nuclear retention. Alternatively, larger size of fusion hY4/5 RNA, conformational interactions between its two RNA domains, or steric hindrance between Ro60 molecules bound to each hY RNA domain could also explain the observed results. Subsequent transfection experiments using hY5–84′O'RNA, a RNA known to bear functional Ro and La binding sites [19], strongly argued against these alternative explanations since Ro RNPs containing this mutated hY RNA were found in the cytoplasmic fraction (Fig. 4b, lane 5).

Discussion

This report demonstrates the predominant nuclear distribution of Ro RNPs containing the primate-specific hY5 RNA (RohY5 RNPs) in cultured human and mouse cells. Nuclear localization was observed in fractionated cells using immunological methods. Similar results were obtained with unfractionated cells by RT-PCR in situ (data not shown). All the other human and murine Ro RNPs were predominantly cytoplasmic. The signal for nuclear localization of RohY5 RNPs appears to be encoded in the sequence of hY5 RNA itself. Apart from the type of hY RNA associated with Ro60, the single major distinction of nuclear Ro antigens was their association with unphosphorylated La protein.

Our results contradict the exclusively cytoplasmic localization of Ro RNPs that was repeatedly reported (reviewed in [15]). Technical limitations in these previous reports probably explain the apparent discrepancies. First, early reports used detergent-based fractionation techniques that allow extensive cytoplasmic leakage of nuclear Ro and La RNPs [6,11]. Secondly, in a recent study using enucleation, almost half of U1 RNPs were found alongside Ro RNPs in cytoplasmic fractions of human cells [15]. This inappropriate distribution of nuclear U1 RNPs likely resulted from significant cytoplasmic leakage of nuclear material during enucleation of human cells. For our part, we have been unable to obtain satisfactory enucleation results using human cells (data not shown). Thirdly, microinjection of hY RNAs in X. laevis oocytes revealed a saturable export pathway for Ro RNPs [12,16]. However, the export of hY5 RNA could not be demonstrated [12]. Fourthly, previous in situ hybridization studies localized hY5 RNA to the cytoplasm [13], but the predicted single-stranded segment of hY5 targeted by the oligonucleotide probes used by Matera et al. may not be present or available for binding in nuclear Ro RNPs. Indeed, deletion of part of this same segment of hY5 prevented interaction with RoBPI, a RohY5 binding protein [28], suggesting that this segment of RNA is involved in nuclear interactions of RohY5 RNPs.

In addition to corroborating prior biochemical results obtained in HeLa cells, transfection of hY RNAs in mouse cells allowed a preliminary definition of the signal for nuclear localization within RohY5 RNPs. First, we reasoned that the hY4 sequence in fusion hY4/5 RNA should be able to associate with the mouse transporter and to guide the resulting RNP to the cytoplasm. As Ro RNPs containing fusion hY4/5 RNA were found in nuclear fractions, the hY5 sequence apparently counteracted actively the export signal present in hY4 RNA sequence. The cytoplasmic localization of Ro RNPs containing the — slightly mutated — hY5-84′O'RNA strongly supported the hypothesis of a nuclear retention of RohY5 RNPs through a specific interaction mediated by hY5 RNA itself. Studies to define more precisely the domain in the hY5 sequence which is responsible for nuclear retention of RohY5 RNPs are in progress (manuscript in preparation).

Ro60 was proposed to have a role in a discard pathway for defective 5S rRNA in X. laevis [29,30] and in Caenorhabditis elegans [31]. A role for Ro60 and an unidentified RNA as co-factors in the regulation of the translational fate of ribosomal protein mRNAs in X. laevis was also suggested [32]. In addition to its canonical, presumably cytoplasmic function [32], primate Ro RNPs (in the form of RohY5 RNPs) may have acquired a unique set of interactions and of consequent functions. Interestingly, we have recently identified through an interaction assay in yeast a RohY5 RNP-specific partner (RoBPI) that belongs to the RNA-binding protein family, has structural similarities with splicing factors, and is predominantly nuclear [28,33]. RoBPI has since been described as a dispensable splicing factor (PUF60) [34] and as a repressor of activated RNA polymerase II transcription (FBP interacting repressor) [35]. Interaction with RoBPI and/or other nuclear proteins, rather than or in addition to binding to La protein, might explain the nuclear retention of RohY5 RNPs.

Autoimmunity to the Ro RNPs is a common feature of connective tissue diseases. In contrast, anti-Ro RNP antibodies are not produced in spontaneously arizing autoimmune mouse models [3]. Intra- and intermolecular epitope spreading observed in autoimmune patients strongly suggest that the immunizing antigen responsible for maintenance of anti-Ro production consists of a human Ro antigen [4,5]. There are several ways to explain how humans can initially lose tolerance to the human Ro antigen. This process may be initiated by association of RohY5 RNPs with an immunizing pathogen. Alternatively, it may be due to molecular mimicry with or to a modification of the Ro antigen itself by an immunogen. While the mechanisms leading to autoantibody production against the Ro particles are not yet defined, it is tempting to speculate that the unique nuclear localization, as well as interactions [28] of RohY5 RNPs bear some relationships to the spontaneous production of antibodies to RohY5 RNPs [7] and to hY5 RNA itself [19,36]. Whether any of their biochemical, immunological and evolutionary specificities relate to a discrete cellular role for RohY5 RNPs remains to be confirmed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Ger J. M. Pruijn (University of Nijmegen, The Netherlands) for providing plasmids pTZR/hY5 and pTZR/hY4 and sharing details of a Northern blot technique, Dr Mark J. Mamula (Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA) for providing rabbit anti-Ro60 sera, Dr Richard J. Maraia (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) for providing vectors phY4 and phY5, Dr Edward K. L. Chan (Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, USA) for providing plasmid pCl encoding human p52 cDNA, Dr Jean-Pierre Perreault (Université de Sherbrooke) for help with the PhosphorImager, and Dr Benoit Chabot (Université de Sherbrooke) for helpful discussions. Final thanks to Elie Barbar and Maximilien Lora for help in preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Tan EM. Antinuclear antibodies: diagnostic markers for autoimmune diseases and probes for cell biology. Adv Immunol. 1989;44:93–151. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60641-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boire G, Ménard HA, Gendron M, Lussier A, Myhal D. Rheumatoid arthritis: anti-Ro antibodies define a non-HLA-DR4 associated clinicoserological cluster. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:1654–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wahren M, Skarstein K, Blange I, Pettersson I, Jonsson R. MRL/lpr mice produce anti-Ro 52 000 MW antibodies: detection, analysis of specificity and site of production. Immunology. 1994;83:9–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keech CL, Gordon TP, McCluskey J. The immune response to 52-kDa Ro and 60-kDa Ro is linked in experimental autoimmunity. J Immunol. 1996;157:3694–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Topfer F, Gordon TP, McCluskey J. Intra- and intermolecular spreading of autoimmunity involving the nuclear self-antigens La (SS-B) and Ro (SS-A) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:875–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.3.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolin SL, Steitz JA. The Ro small cytoplasmic ribonucleoproteins: identification of the antigenic protein and its binding site on the Ro RNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1996–2000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.7.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boire G, Craft J. Biochemical and immunological heterogeneity of the Ro ribonucleoprotein particles. Analysis with sera specific for the RohY5 particle. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:270–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI114150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maraia RJ, Sakulich AL, Brinkmann E, Green ED. Gene encoding human Ro-associated autoantigen Y5 RNA. Nucl Acids Res. 1996;24:3552–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.18.3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boire G, Craft J. Human Ro ribonucleoprotein particles: characterization of native structure and stable association with the La polypeptide. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:1182–90. doi: 10.1172/JCI114551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green CD, Long KS, Shi H, Wolin SL. Binding of the 60-kDa Ro autoantigen to Y RNAs: evidence for recognition in the major groove of a conserved helix. RNA. 1998;4:750–65. doi: 10.1017/s1355838298971667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hendrick JP, Wolin SL, Rinke J, Lerner MR, Steitz JA. Ro small cytoplasmic ribonucleoproteins are a subclass of La ribonucleoproteins: further characterization of the Ro and La small ribonucleoproteins from uninfected mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1981;1:1138–49. doi: 10.1128/mcb.1.12.1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simons FHM, Pruijn GJM, van Venrooij WJ. Analysis of the intracellular localization and assembly of Ro ribonucleoprotein particles by microinjection into Xenopus laevis oocytes. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:981–8. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.5.981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matera AG, Frey MR, Margelot K, Wolin SL. A perinucleolar compartment contains several RNA polymerase III transcripts as well as the polypyrimidine tract-binding protein, hnRNP I. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:1181–93. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.5.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farris AD, Puvion-Dutilleul F, Puvion E, Harley JB, Lee LA. The ultrastructural localization of 60-kDa Ro protein and human cytoplasmic RNAs: association with novel electron-dense bodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3040–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pruijn GJM, Simons FHM, van Venrooij WJ. Intracellular localization and nucleocytoplasmic transport of Ro RNP components. Eur J Cell Biol. 1997;74:123–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simons FHM, Rutjes SA, van Venrooij WJ, Pruijn GJM. The interactions with Ro60 and La differentially affect nuclear export of hY1 RNA. RNA. 1996;2:264–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feeney RJ, Sauterer RA, Longo Feeney J, Zieve GW. Cytoplasmic assembly and nuclear accumulation of mature small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:5776–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi MH, Tsui FWL, Rubin LA. Cellular localization of the target structures recognized by the anti-Jo-1 antibody: immunofluorescence studies on cultured human myoblasts. J Rheumatol. 1991;18:252–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Granger D, Tremblay A, Boulanger C, Chabot B, Ménard HA, Boire G. Autoantigenic epitopes on hY5 Ro RNA are distinct from regions bound by the 60-kDa Ro and La proteins. J Immunol. 1996;157:2193–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adam SA, Sterne Marr R, Gerace L. Nuclear protein import in permeabilized mammalian cells requires soluble cytoplasmic factors. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:807–16. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.3.807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore MS, Blobel G. The two steps of nuclear import, targeting to the nuclear envelope and translocation through the nuclear pore, require different cytosolic factors. Cell. 1992;69:939–50. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90613-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bretscher MS, Munro S. Cholesterol and the Golgi apparatus. Science. 1993;261:1280–1. doi: 10.1126/science.8362242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mamula MJ, O'Brien CA, Harley JB, Hardin JA. The Ro ribonucleoprotein particle: induction of autoantibodies and the detection of Ro RNAs among species. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1989;52:435–46. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(89)90158-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boire G, Gendron M, Monast N, Bastin B, Ménard HA. Purification of antigenically intact Ro ribonucleoproteins; biochemical and immunological evidence that the 52-kD protein is not a Ro protein. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;100:489–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb03728.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maraia RJ, Sasaki-Tozawa N, Driscoll CT, Green ED, Darlington GJ. The human Y4 small cytoplasmic RNA gene is controlled by upstream elements and resides on chromosome 7 with all other hY scRNA genes. Nucl Acids Res. 1994;22:3045–52. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.15.3045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fan H, Sakulich AL, Goodier JL, Zhang X, Qin J, Maraia RJ. Phosphorylation of the human La antigen on serine 366 can regulate recycling of RNA polymerase III transcription complexes. Cell. 1997;88:707–15. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81913-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lopez-Luna A, Ramirez-Santoyo RM, Barbosa-Cisneros OY, Avalas-Diaz E, Moreno J, Herrera-Espavza R. Phosphorylation profiles of 60 kD Ro antigen in synchronized HEp-2 cells. Scand J Rheumatol. 1995;24:293–9. doi: 10.3109/03009749509095166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bouffard P, Barbar E, Brière F, Boire G. Interaction cloning and characterization of RoBPI, a novel protein binding to human Ro ribonucleoproteins. RNA. 2000;6:66–78. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200990277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Brien CA, Wolin SL. A possible role for the 60-kD Ro autoantigen in a discard pathway for defective 5S rRNA precursors. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2891–903. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.23.2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi H, O'Brien CA, van Horn DJ, Wolin SL. A misfolded form of 5S rRNA is complexed with the Ro and La autoantigens. RNA. 1996;2:769–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Labbé JC, Hekimi S, Rokeach LA. The levels of the RoRNP-associated Y RNA are dependent upon the presence of RoP-1, the Caenorhabditis elegans Ro60 protein. Genetics. 1999;151:143–50. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.1.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pellizzoni L, Lotti F, Rutjes SA, Pierandrei-Amaldi P. Involvement of the Xenopus laevis Ro60 autoantigen in the alternative interaction of La and CNBP proteins with the 5′UTR of L4 ribosomal protein mRNA. J Mol Biol. 1998;281:593–608. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bouffard P, Wellinger RJ, Brière F, Boire G. Identification of ribonucleoprotein (RNP)-specific protein interactions using a yeast RNP interaction trap assay (RITA) Biotechniques. 1999;27:790–6. doi: 10.2144/99274rr02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Page-McCaw PS, Amonlirdviman K, Sharp PA. PUF60: a novel U2AF65-related splicing activity. RNA. 1999;5:1548–60. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299991938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu J, He L, Collins I, Ge H, Liutti D, Li J, Egly JM, Levens DL. The FBP interacting repressor targets TFIIH to inhibit activated transcription. Mol Cell. 2000;5:331–41. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80428-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boulanger C, Chabot B, Ménard HA, Boire G. Autoantibodies in human anti-Ro sera specifically recognize deproteinized hY5 Ro RNA. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;99:29–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb03468.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]